Quinqueviri of Asisium

As Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at pp. 237-8) observed that, in the period after municipalisation but before the Perusine War (41-40 BC):

-

“Beside the quattuorviri [in AE 1981, 0371 and CIL XI 8021, below] appear the names of five men identified as [holding the magistracy entitled] quinqueviri” (my translation).

He then discussed four surviving inscriptions that record men who served (or probably served) as quinqueviri at Asisium:

-

✴CIL XI 8021, which relates to the construction of a terrace wall along the eastern edge of what is now Piazza del Comune;

-

✴AE 1981, 0317, which relates to the paving of this piazza; and

-

✴two almost identical inscriptions, each of which relates to the construction of a wall in an unknown location:

-

•CIL XI 5392, which was found in Piazza del Comune ( now the Museo Civico); and

-

•CIL XI 5391, which is from an unknown location (now embedded in the entrance wall of the Palazzo del Podestà of Bettona).

These inscriptions are discussed in turn in the sections below.

Construction of Terrace Wall

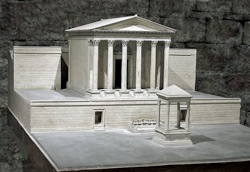

The original pavement in front to the so-called Temple of Minerva, which was discovered in 1839, some 5 metres below the present paving of Piazza del Comune, can be visited from the Museo Civico. A long inscription (CIL XI 8021, 89-40 BC) exhibited on the terrace wall under the pronaus of the temple originally recorded the names of seven magistrates:

-

✴the two quattuorviri iure dicundo, whose names have been lost;

-

✴the quinqueviri:

-

•C(aius) Babrius Chilo, son of C(aius);

-

•C(aius) Veistinius Capito, son of C(aius);

-

•C(aius) Vallius, son of C(aius);

-

•L(ucius) Visellius, son of L(ucius); and

-

•Cn(aeus) Veistinius, son of Cn(aeus).

The last line of this part of the inscription has been completed as:

mu[rum faciundum curarunt probaruntque]

thus recording that these seven men arranged for and approved the construction of the wall. A separate line below records that Caius Attius Clarus, son of Titus paid for its stucco decoration.

Paving of the Piazza in front of the ‘Temple of Minerva’

Reconstruction of the so-called Temple of Minerva (Museo Civico)

The tribunal in front of the terrace wall discussed above and the tetrastyle towards the centre of the original piazza in front of it partly obscure holes in the paving that were left by the bronze letters of an inscription. The holes that remain unobscured are found on 13 marble blocks (illustrated in the EAGLE database - see the AE link below) that are perfectly aligned with the axis of the temple itself. Although these blocks were discovered in 1839, a transcription of the inscription (AE 1981, 0317, 89-40 BC) was only published in 1981. It records:

-

✴the quattuorviri iure dicundo:

-

•C(aius) Caetronius [?]ar(ius?), son of C(aius); and

-

•C(aius) Attius Ruf(ius), son of C(aius); and

-

✴two other men whose magistracy was probably recorded on the stones now under the tetrastyle:

-

•T(itus) Olius Gargenna, son of C(aius); and

-

•L(ucius) Ca[..]tius B....., son of C(aius).

Scholars generally assume that these last two men were quinqueviri: thus Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 238) suggested that:

-

“... the names of another three men [i.e. the other three quinqueviri] and a final formula of the type ‘senatus consulto faciundum coiravere’ were [probably] obliterated by the tetrastyle that was built above” (my translation).

Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 357, entry 13B) suggested that the family name of the quinquevir L(ucius) Ca[..]tius B....., son of C(aius) could have been Caelius, Callus or Cattius.

Enrico Zuddas described (at pp. 359-60) another block that was found in 1969 near the steps to the left that led up to the pronaus of the temple, with evidence of an inscription that can be restored as:

[... ]ca Cn(aeus) Fuficius [....]

He suggested that this block could have been the 14th in the series discussed here. In that case:

-

✴L(ucius) Ca[..]tius B....., (above) might have been L(ucius) Ca[..]tius B..... [Perti ?]ca; and

-

✴ Cn(aeus) Fuficius [....] would have been a third quinquevir. He could have been (or been the father of) Cnaeus Fuficius Laevinus, son of Cnaeus, recorded as quattuorviri iure dicundo in CIL XI 5391-2 below.

CIL XI 5391-2

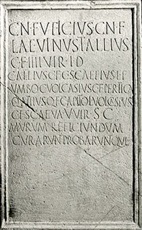

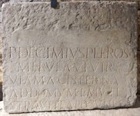

CIL XI 5392 (Museo Civico, Assisi) CIL XI 5391 (Palazzo del Podestà at Bettona)

As noted above, these two inscriptions, both of which date to the last three decades of the 1st century BC, contain essentially identical texts:

-

✴CIL XI 5392 (now in the Museo Civico) was apparently found near the church of San Nicolò in Piazza del Comune. It records the restoration of a wall by:

-

•the quattuorviri iure dicundo:

-

-Cnaeus Fuficius Laevinus, son of Cnaeus; and

-

-Titus Allius, son of Caius; and

-

•the quinqueviri:

-

-[Caius] Allius, son of Caius;

-

-Caius Scaefius Umbo, son of Lucius;

-

-Caius Volcasius Pertica, son of Caius;

-

-Quintus Attius Capito, son of Quintus; and

-

-Lucius Volcasius Scaeva, son of Caius.

-

✴CIL XI 5391 (now embedded in the entrance wall of the Palazzo del Podestà at Bettona) is from an unknown location. It is identical to CIL XI 5392, except that the names of the quattuorviri are given in the reverse order.

Although it is possible that one or both of these refer to a restoration of the walls of Bettona, it is much more likely (given the form of the magistracies) that they both came from Assisi. They could have commemorated the restoration of part the city walls: however, Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 280) suggested that they more probably related to the restoration of a wall supporting a terrace (perhaps one of those near the so-called Temple of Minerva) that required restoration in the late 1st century BC.

Character of the Quinquevirate at Asisium

Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, at p. 20) suggested that:

-

“The presence of quinqueviri (a college that is unknown in any other inscriptions from Assisi) on three occasions in the same building complex makes it likely that we are dealing with a (possibly priestly) college that was closely connected to the so-called Temple of Minerva ...” (my translation).

Giovanna Asdrubali Pentiti (referenced below, at p. 103) found this hypothesis “suggestive”, but pointed out that the inscriptions CIL XI 5391-2 were not securely associated with the site of the so-called Temple of Minerva. She concluded that:

-

“... it is preferable to consider the quinqueviri of Assisi as members, not of a priestly college, but rather of an extraordinary commission elected [by the members of the local senate for construction projects in the period following municipalisation]” (my translation).

Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 238) observed that this second hypothesis is accepted by most scholars.

It seems from these inscriptions that the quinqueviri of Asisium undertook construction projects under the supervision of the quattuorviri iure dicundo. Giovanna Asdrubali Pentiti (referenced below, at p. 103) pointed out that they:

-

“... were apparently chosen from a restricted number of [important] local families ]...and were not comparable to colleges of quinqueviri recorded elsewhere [CIL IX 5070, 5072, 5276 and CIL V 1883] ..., which were almost entirely made up of freedmen” (my translation).

Marjeta Šašel Kos (referenced below, at p. 705) reinforced this point with reference to a wider range of municipal quinqueviri, most, if not all of which were freedmen.

Before the Perusine War

We know (from CIL XI 8021 and AE 1981, 0317) the names of seven, or possibly eight, men who served as quinqueviri on projects carried out before the Perusine War. The families of two of them (the gens Valia and the gens Visellia ) are otherwise unknown. The families of the other five are discussed briefly below.

Gens Babria

Caius Babrius Chilo, son of Caius, appeared as a quinquevir in CIL XI 8021.

-

Nero Babrius, son of Titus held two municipal post before municipalisation: he appeared as a marone in CIL XI 5390 (late 2nd century BC) and as a uhter in ST Um 10 (CIL XI 5389, 120 - 90 BC).

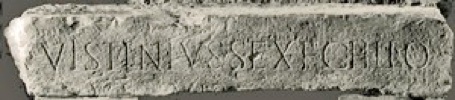

Gens Veistinia/ Vestinia/ Vistinia

Both Caius Veistinius Capito, son of Caius, and Cnaeus Veistinius, son of Cnaeus, appeared as quinqueviri in CIL XI 8021.

-

Caius Vestinius, son of Vibius appeared as a uhter in ST Um 10 (CIL XI 5389, 120 - 90 BC).

-

Titus Vistinius Vìto appeared among the seviri recorded in CIL XI 5424 and AE 1989 0290 (7BC), as discussed below.

-

Sextus Vistinius Chilo, son of Sextus is recorded as a sevir, or perhaps a sevir Augustale, in his funerary inscription CIL XI 5426 (1st half of the 1st century AD), as discussed below.

Gens Olia/ Ollia

Titus Olius Gargenna, son of Caius appeared as a quinquevir in AE 1981, 0317.

-

Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 357) asserted that the gens Olia probably come from Cupra Marritima. A later member of this family, also Titus Olius, was a senator who died with Sejanus after the failure of the plot against Tiberius in 31 AD. His widow was Poppea Sabina, who seems to have owned a property near Assisi, as evidenced by an inscription (CIL XI 5418, 30-50 AD) that is now in the Museo Civico. Their daughter, also Poppea Sabina, became the wife of the Emperor Nero.

-

-

Gens Fuficia

-

Cnaeus Fuficius was possibly the third quinquevir of AE 1981, 0317 (as discussed above).

-

He might have been (or been the father of) Cnaeus Fuficius Laevinus, son of Cnaeus, recorded as quattuorviri iure dicundo in CIL XI 5391-2 (30-1 BC).

After the Perusine War

We know from (CIL XI 5391-2) the name of the five men from four families who served together as quinqueviri at some time in the period 30-1 BC. These families are discussed briefly below.

Gens Attia

Quintus Attius Capito, son of Quintus:

-

Caius Attius Rufius, son of Caius, appeared as a quattuorvir iure dicundo in AE 1981, 0317 (90-40 BC).

-

Caius Attius Clarus, son of Titus appeared in CIL XI 8021 (90-40 BC), but without career details.

Gens Volcasia

Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 280) suggested that the quinqueviri Caius Volcasius Pertica and Lucius Volcasius Scaeva, both sons of Caius, might have been be brothers.

-

Titus Volcasius Cinnamus, who was probably a freedman of the gens Volcasia, is recorded as a sevir Augustales in his funerary inscription CIL XI 5427 (1st half of the 1st century AD), as discussed below.

Gens Allia

[Caius] Allius, son of Caius:

-

Caius Allius Crispus appeared as a quattuorvir in CIL XI 5396 (2nd half of the 1st century AD).

Gens Scaefia

Caius Scaefius Umbo, son of Lucius:

-

Caius Scaefius Sulpicianus appeared in CIL XI 5416, (2nd century AD) as a patron of Asisium and holder of two municipal posts: quattuorvir iure dicundo quinquennale and, on two occasions, quaestor.

Conclusions

It seems that the quinqueviri of Asisium belonged to the local élite. Three of the seven (or possibly eight) who served before the Perusine War belonged to families that had already reached the top of the administration of Asisium before municipalisation. They seem to have been appointed by the local senate in connection with specific construction projects: it is possible that the projects in question were financed by their summae honoriae (the payments that they made for the privilege of their appointments).

We know of only one group of quinqueviri after the Perusine War. Again, they were connected as a group with either one or a pair of construction projects. One of this group, Quintus Attius Capito, came from a family that had provided at least one quattuorvir in the pre-war period, which suggests that the family had been loyal to Octavian during the war. In addition, Cnaeus Fuficius, who had possibly been a quinquevir before the war, might have been (or been the father of) Cnaeus Fuficius Laevinus, son of Cnaeus, who became quattuorviri iure dicundo thereafter. The other four members of this post-war group of quinqueviri could have been ‘new men’, and perhaps even new arrivals at Asisium: their families seem to have continued to prosper at Asisium thereafter.

The most striking of all these ‘family careers’ discussed above is that of the gens Veistinia/ Vestinia/ Vistinia. As we have seen:

-

✴Caius Vestinius, son of Vibius had served as a uhter, the most senior administrative post at Asisium before municipalisation;

-

✴both Caius Veistinius Capito and Cnaeus Veistinius served as quinqueviri before the Perusine War;

-

✴Titus Vistinius Vìto served as a sevir in 7 BC;

-

✴Sextus Vistinius Chilo, son of Sextus served as a sevir, or perhaps a sevir Augustale, in the 1st half of the 1st century AD.

These last three appointments suggest a degree of continuity, at least initially, between the quinqueviri of the 1st century BC and the seviri/ seviri Augustales of the subsequent period. This hypothesis is developed further below.

Seviri at Asisium

Henrik Mouritsen (referenced below at p. 237) summarised the history of scholarship on the seviri, seviri Augustales and magistri Augustales of the municipia of Italy:

-

“The time of Augustus ... experienced the rapid spread of two new civic titles - the Augustales [including seviri Augustales and magistri Augustales] and the seviri - who feature in hundreds of inscriptions from virtually every town in Italy. ... For more than 100 years, scholars have systemised [these inscriptions and other evidence], formulating theories about the organisational structure [of the respective magistracies], their membership, their civic and religious functions, and their status in the local community. Initially, they were seen as priests of the imperial cult, but this view has since been challenged ... it has [now] become fashionable to emphasise their role as a civic ordo, ranking well above the plebs and immediately below the decurions.”

Mouritsen himself argued (at pp. 244-5) against the existence of a formal ‘ordo’. Instead, he developed (at pp. 242-3) a model in which:

-

“The posts were honores but, unlike the [other civic] magistracies on which they were modelled, [they] had no civic authority. Theirs were, quite literally, empty honours, which held neither actual power nor ... any defined civic remit or function. ... [We might usefully] focus on the one element that made these honores real - which was their cost ... : the office-holders still had to pay their summa honoraria [entrance fee due to the municipality]. ... These posts therefore represented attempts to widen the pool of public donors ... The new honores ... could be held by anyone, irrespective of birth, provided they had sufficient wealth.”

These magistracies thus provided a route by which men who were excluded from municipal power, often because of their status as freedmen, were nevertheless able to achieve civic prominence, provided that they could afford it.

According to Margaret Laird (referenced below, at p. 8, note 27), the earliest of the securely-dated records of this type of magistracy is CIL XI 3200 is from the Nepet (now Nepi, some 50 km north of Rome). It read:

Imp(eratori) Caesari Divi f(ilio) / Augusto

pontif(ici) maxim(o), co(n)s(uli) XI/ tribunic(ia) potestat(e) XI

magistri Augustal(es) prim(i):

Philippus Augusti libert(us)

M(arcus) Aebutius Secund[us]

M(arcus) Gallius Anchia[lu]s

P(ublius) Fidustius Antigonus

It records the first college of four magistri Augustales at Nepet, which was established in the year of Augustus’ 11th consulate and the 11th year of his tribunician power (i.e. in 12 BC). The first of these new magistrates is explicitly identified as a libertus (freedman: judging from their names, each of the other three probably shared this status or was descended from a man who had. The EAGLE database (see the CIL link) comments:

-

“This is the oldest record of the imperial cult in Etruria, dating to the year that also saw the establishment of the [‘proto-imperial’] cults of ‘Genius Augusti’ and ‘Lares Augusti’ at Rome” (my translation).

However, there is no explicit evidence that either the magistri Augustales (at Nepet or anywhere else) or the more ubiquitous Augustales and seviri Augustales were priests of the imperial cult. The word ‘Augustale’ might be expected to imply a dedication to the worship of Augustus: however, as Henrik Mouritsen (referenced below, at p. 238) observed:

-

“... if we look at the epigraphic documentation for [seviri Augustales and seviri, for example], it becomes clear that there is no substantial differences between them [in relation to] membership, duties and function, or public profiles.”

As we shall see below, this seems to be borne out by the surviving evidence at Asisium.

This does not mean that the seviri and seviri Augustales had no cult functions: as Margaret Laird (referenced below, at p. 7) pointed out:

-

“The public role of [Augustales, seviri Augustale and seviri] inevitably involved them in the performance of religious rituals, some of which honoured emperors and members of the imperial family. In this regard, [they] parallel many other groups and individuals (including [civic magistrates] and members of professional guilds) that similarly overlaid emperor worship onto civic spectacle and euergetism [public works].”

As noted above, the four magistri Augustales at Nepet were (or were probably) freedmen, and freedmen were conspicuous among the members of the other comparable magistracies. However as Henrik Mouritsen (referenced below, at p. 247) pointed out:

-

“[These magistracies were not] exclusively reserved for freedmen ...: there are many examples of freeborn Augustales and seviri, albeit with great regional and chronological variations. ... [There is also] considerable intra-regional diversity ...: [For example,] at Hispellum, seven out of ten severi were explicitly freeborn [as discussed in my page on Seviri and Seviri Augustales at Hispellum], in sharp contrast to nearby Asisium, where that applied to just three [inscriptions: AE 1989 0290 ; CIL XI 5424; and CIL XI 5426] out of 23.”

Freeborn Seviri at Asisium

Two of these three inscriptions cited by Mouritsen date to the consulate of Tiberius and Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso (i.e. to 7 BC):

-

✴The inscription (AE 1989 0290) from an unknown location in Asisium, which is now in a courtyard of the nunnery of Santa Chiara, reads

-

[Ti(berio) Cl]audio Nerone II, Cn(aeo) Calpurnio/ Pisone co(n)s(ulibus)

-

[Sex(tus) Ve]turius C(ai) f(ilius), VIvir

-

T(itus) Vistinius Vìtor, VIvir

-

C(aius) Quìntius/ [- - -]us, VIvir

-

C(aius) [An]tonius Tertius, VIvir

-

C(aius) Diburnius/ [- - - VI]vir

-

[- - -]M[·]Ṛ[+2?+] Cn(aei) f(ilius) Sator, [-]/

-

[- - -] straverunt/ ḍ(ecreto) d(ecurionum)

-

According to Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 366):

-

“This inscription records that the seviri and two other men, perhaps quattuorviri or aediles, financed at their own expense the paving of a road” (my translation).

-

Unfortunately , the lower part of the inscription is very damaged, and the sixth sevir and the two other men are now anonymous.

-

-

✴A fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 5424) in the facade of the Palazzo dei Canonici della Cattedrale (to the left of the lower lefthand window) replicates the first part of the text above:

-

Ti(berio) Claudio Nero[ne (iterum), Cn(aeo) Calpurnio Pisone co(n)s(ulibus)]

-

Sex(tus) Veturius C(ai) f(ilius) VIvir, T(itus) Vìstị[nius Vitor] ...

According to Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 295):

-

“We are dealing here with the earliest [securely dated] attestation of the title ‘severi’, unqualified by the word ‘Augustales” (my translation).

Thus, we might reasonably assume that the magistracy of the seviri of Asisium was established in or shortly before 7 BC.

The third inscription (CIL XI 5426, 1st half of the 1st century AD), which came from an unknown location is Assisi (now in the Museo Civico), commemorates [Sextus] Vistinius Chilo, son of Sextus, who was probably a sevir Augustales (although the second line of the inscription, which names the magistracy,is mostly lost).

The three men whom Henrik Mouritsen deemed to be explicitly freeborn were thus:

-

✴the sevir Sextus Veturius, son of Caius: and

-

✴two men from the aristocratic gens Veistinia/ Vestinia/ Vistinia (discussed above):

-

✴the sevir Titus Vistinius Vitor (who, surprisingly, is not given a filiation); and

-

✴the (probable) sevir Augustale [Sextus] Vistinius Chilo, son of Sextus.

The surviving evidence therefore suggests that the participation of freeborn men in these magistracies died out in the early 1st century AD, when they became essentially the preserve of freedmen.

Functions of the Seviri

As noted above, magistracies such as the seviri provided a route by which individuals, particularly those who were excluded from municipal power (often because of their status as freedmen) were nevertheless able to achieve civic prominence, provided that they could afford it.

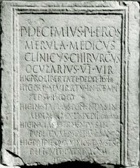

P(ublius) Decimius P(ublii) l(ibertus) Eros/ Merula

medicus/ clinicus, chirurgus/ ocularius, VIvir

hic pro libertate: dedit HS [50,000]

hic pro seviratu in rem p(ublicam):/ dedit HS [2,000]

hic in statuas ponendas in/ aedem Herculis: dedit HS [30,000]

hic in vias sternendas/ in publicum: dedit HS [37,000]

hic pridie quam mortuus est/ reliquit patrimony: HS [800,000 ?]. . .

This records that the freedman Publius Decimius Eros Merula, who was by profession a clinical physician, surgeon and oculist, paid:

-

✴50,000 sesterces for his freedom;

-

✴2,000 sesterces to the municipal treasury in return for his election to the sevirate;

-

✴30,000 sesterces towards statues placed in the Temple of Hercules; and

-

✴37,000 sesterces to the municipal treasury for the paving of streets.

In addition, on the day before he died, he bequeathed an estate of perhaps 800,000 sesterces (although there is uncertainty here) to the municipium. According to Margaret Laird (referenced below):

-

✴“The [amount] that Eros Merula donated to place statues in the Temple of Hercules ... would have been sufficient for five or six marble images, a programmatic intervention in the temple or its precinct” (p. 217); and

-

✴“... Eros Merula’s gift [for paving projects] could have surfaced [ca. 480 meters] of Asisium’s streets. Because the distance between Asisium’s main public monuments and the city’s walls rarely surpasses 300 meters, Merula could have paved several stretches throughout the town” (p. 235).

She observed (at p. 221) that:

-

“Eros Merula’s donations of statuary and money for paving reflect but two possibilities [for euergetism that were open to seviri and similar magistrates. Others] gave buildings, banquets or games to their communities.”

In return, they could expect epigraphic commemoration and a number of other manifestations of their enhanced social status.

Paving Projects

So far we have considered two paving projects at Asisium associated with seviri:

-

✴the unspecified project recorded in AE 1989, 0290 and CIL XI 5424 (assuming these inscriptions related to a single project); and

-

✴the extensive programme undertaken by Eros Merula, evidenced by CIL XI 5400.

P(ublius) Decimius P(ubli) l(ibertus) Eros/ Merula VIvir

viam a cisterna/ ad domum L(uci) Muti/ stravit ea pecunia/ ...

It thus records that Publius Decimius Eros Merula financed the paving of a road from a cistern to the house of Lucius Mutius.

These four inscriptions, together with CIL XI 5371, discussed below, constitute the only surviving records of the euergetism of the seviri/ seviri Augustales at Asisium. They probably give a misleading impression of the relative importance of paving projects: Margaret Laird (referenced below, at p. 248 and note 66) pointed out that a survey across the Italian municipia indicated that the number of surviving inscriptions relating to expenditure by magistracies of this kind on such infrastructure projects was significantly exceeded by similar inscriptions recording expenditure on statues and cult objects (such as Eros Merula’s project at the Temple of Hercules), games, banquets and buildings. Nevertheless, as Margaret Laird (referenced below, at p. 247) pointed out:

-

“During the principate [of Augustus, in 27 BC - 14 AD], the donor pool [for such infrastructure projects] expanded to include individuals like the sevir P. Decimus Eros Merula and other civic élites.”

She produced (as her Appendix 3) a list of some 140 municipal projects involving street-paving and bridge-building in Italy that are evidenced by inscriptions. The 15 of these projects that she identified in Regio VI (Umbria) comprised:

-

✴2 (or perhaps 3) that were sponsored by private individuals;

-

✴6 (or perhaps 5) sponsored by civic magistrates;

-

✴5 sponsored by seviri or seviri Augustales, including those at Asisium evidenced by CIL XI 5399 and 5400 (to which she ought to have added that evidence by AE 1989, 0290/ CIL XI 5424); and

-

✴2 at Mevania that were evidenced by CIL XI 5040 and 5041, both of which were sponsored by the magistri/novemviri Valetudinis (although she did not connect the second of these inscriptions with this magistracy, presumably because the part of the inscription that almost certainly identified it has been lost and is unrecorded).

(As I discuss in my page on Bevagna: Valetudo and the Magistri/ Novemviri Valetudinis, this analysis supports the view that the the magistri/novemviri Valetudinis, a magistracy that was unique to Mevania, was similar in important respects to the seviri/ seviri Augustales at Asisium and elsewhere.)

Religious Projects

Bonum/ Eventum

municipio/ municipibus et incolis Asi/sinatibus,

Q(uintus) Tìresius/ Primigeni lib(ertus) Campan/us

VIvir Aug(ustalis)

S(enatus) C(onsulto) L(ocus) D(atus)

It records the dedication, by the freedman and sevir Augustale Quintus Tìresius Primigenus Campanus, of an altar to the deity Bonus Eventus in a place given by the local senate, in order to promote the good fortune of the citizens and other residents of Asisium.

Funerary Inscriptions

All of the remaining epigraphic evidence for seviri and seviri Augustales at Asisium for whom we have names is in the form of funerary inscriptions commemorating men who were (or were probably) freedmen. They all belong to the 1st or 2nd century AD.

Titus Baebius Apollonius

A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5397, 1st half of the 1st century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi (now in the Museo Civico) commemorates the freedman and sevir Titus Baebius Apollonius and Baebia Prima, who was probably his wife.

Quintus Vibius Modestus

Titus Volcasius Cinnamus

A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5427, 1st half of the 1st century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi (now in the Museo Civico) contains a dedication to the sevir Augustale Titus Volcasius Cinnamus and his wife, Vettia Saturnina from their daughter, Volcasia Saturnina (recorded in her own funerary inscription: CIL XI 5428, 1st half of the 1st century AD). The ‘Greek’ cognomen ‘Cinnamus’ suggests that Titus Volcasius was a freedman of the gens Volcasia: other known liberti of this family include Caius Volcasius Chrestus Naso (CIL XI 5571, 1st century AD) and Volcasia Hospita (CIL XI 5572, 1st century AD).

Cnaeus Caesius Iucundus

A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5398, 1st century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi (now in the Museo Civico) commemorates the freedman and sevir Cnaeus Caesius Iucundus. He had probably been freed by Cnaeus Caesius Tiro, one of the two brothers who, as quattuorviri, built the so-called Temple of Minerva.

Lucius Titius ... (1st half of the 1st century AD) [23]

Caius Nonius Sextius

A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5403, 1st century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi (now in a private collection) commemorates the freedman and sevir Caius Nonius Sextius.

Caius Publicus Asisinatium Verecundus

A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5411, 1st century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi (now in the Museo Civico) contains a dedication from Caius Publicus Allius Pr[...] to his father, Caius Publicus Asisinatium Verecundus, a freedman of the municipium and sevir Augustale.

Caius Propertius Repentinus

A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5410, 2nd half of the 1st century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi (now in the Museo Civico) contains a dedication from the freedman Caius Propertius Merula to another freedman, Caius Propertius Repentinus, a sevir Augustale. {Both men had belonged to the gens Propertia, the family of the poet Propertius)

Caius Quintius Agathemerus

A now lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5412, 1st or 2nd century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi commemorated the freedman Caius Quintius Fortunatus, who had died aged only 20. The monument had been erected by his patron, Caius Quintius Agathemerus, a doctor and seviri: as Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 290) pointed out, the ‘Greek’ cognomen Agathemerus indicated that Quintius was also a freedman.

Caius Aburius Capella

Lucius Velius Cerialis

A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5421, 2nd century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi (now in the nunnery of San Damiano) commemorates the sevir Lucius Velius Cerialis and his wife, Maria Optata: Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 294) suggested that both Velius Cerialis and his wife were probably liberti.

Quintus Veianius Himerus

-

“The hunting scene perhaps alludes to an event organised by the deceased, a freedman of the gens Veiania, on the occasion of his nomination as sevir Augustale” (my translation).

Caius Aburius Amphio

A now lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5393) from an unknown location in Assisi commemorated the freedman and sevir Caius Aburius Amphio. Unfortunately, this inscription is only known from a transcription, and cannot be dated.

Anonymous

The surviving epigraphic evidence for seviri and seviri Augustales whose names have been lost comprises:

-

✴a funerary inscription (CIL XI 5431, 1st century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi (now in the Museo Civico), which commemorates a now-anonymous man with the praenomen Sextus, who was probably a sevir Augustale;

-

✴a now lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5402, 1st or 2nd century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi, which commemorated two now-anonymous freedmen, at least one of whom was a sevir;

-

✴a now lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5429, 1st or 2nd century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi, which commemorated a now-anonymous sevir;

-

✴a now lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5412, 1st or 2nd century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi, which commemorated a now-anonymous freedman and sevir Augustale; and

-

✴a now lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5401, 1st or 2nd century AD) from an unknown location in Assisi, which commemorated a now-anonymous sevir Augustale, whose cognomen was Fortunatus.

Conclusions

I noted above that the quinqueviri of Asisium, who were documented in the 1st century BC, seem to have been appointed by the local senate in connection with specific construction projects: it is possible that the projects in question were financed by their summae honoriae (the payments that they made for the privilege of their appointments). The most recent evidence for collective action of this kind is in the inscriptions CIL XI 5391-2, which date to the period 30-1 BC. The earliest and only records of euergetism of this kind on the part of the seviri are found in the (probably originally identical) inscriptions AE 1989 0290 and CIL XI 5424 of 7 BC: it is possible that the paving project recorded here was financed by the summae honoriae of what was in all probability the first college of seviri at Asisium. Thus it seems that the quinqueviri and seviri were operating in a similar way at about the same time.

We also observe the participation in both colleges of members of the gens Veistinia/ Vestinia/ Vistinia: as noted above:

-

✴both Caius Veistinius Capito and Cnaeus Veistinius were recorded as quinqueviri before the Perusine War;

-

✴Titus Vistinius Vìto served in the college of seviri in 7 BC; and

-

✴for good measure, we know from his funerary inscription that Sextus Vistinius Chilo, son of Sextus served as a sevir, or perhaps a sevir Augustale, in the 1st half of the 1st century AD.

However, while all of the quinqueviri for whom we have names were freeborn, only three seviri have been identified in the surviving records as sharing this status:

-

✴Titus Vistinius Vìto;

-

✴Sextus Veturius, son of Caius, his colleague in 7 BC; and

-

✴Sextus Vistinius Chilo, son of Sextus.

It is thus possible that the magistracy of the quinqueviri of the 1st century BC was effectively replaced in or shortly before 7 BC by the seviri: membership of the new magistracy was open to freedmen, which introduced a new pool of finance for the administration and urban development of the municipium. The earliest surviving records of seviri Augustales at Asisium date to the 1st half of the 1st century AD:

-

✴It is possible that this was a separate magistracy, albeit that surviving evidence suggests that the seviri and seviri Augustales had very similar characteristics and functions.

-

✴However, it is also possible that these were simply alternative names for the same magistracy.

Very quickly, freedmen effectively took over the seviri/ seviri Augustales, thereby gaining access to what was, in effect, a new stratum of society. In this context, it is interesting to note that, when Galeo Tettienus Pardalas and his wife (or mother) Tettiena Galene erected the tetrastyle outside the so-called Temple of Minerva for statues of Castor and Pollux (as evidenced by CIL XI 5372, 14-68 AD), they distributed:

-

✴5 denari to each decurione;

-

✴3 denari to each of the seviri; and

-

✴a denarius to each of the plebs.

Galeo Tettienus Pardalas was almost certainly a freedman of the gens Tettiena, and it is possible that he singled out the seviri (presumably those currently serving and those who had previously served in this capacity) for a relatively high distribution because he was among their number. However, it is alternatively possible that he made this distinction in recognition of the seviri as a distinct social class, between the decurions and the plebs.

Read more:

M. Šašel Kos, “Quinqueviri in Aquileia and Emona?”, Antichità Altoadriatiche, 85 (2016) 699-710

M.Laird, “Civic Monuments and the 'Augustales' in Roman Italy”, (2015 ) New York

E. Zuddas, “Asisium: Aggiunte e Correzioni ai Monumenti Epigrafici Compresi nelle Raccolte che si Aggiornano”, Supplementa Italica, 23 (2007) 268-347

H. Mouritsen, “Honores Libertini: Augustales and Seviri in Italy”, Hephaistos, 24 (2006) 237-48

G. Asdurabli Pentiti, entry 22, in:

M. Matteini Chiari (Ed.), "Raccolte Comunale di Assisi", Milan (2005)

F. Coarelli, "Assisi Repubblicana: Riflessioni su un Caso di Autoromanizzazione", Atti Accademia Properziana del Subasio, (1991) Assisi

G. Forni (Ed.), “Epigrafi Lapidarie Romane di Assisi”, (1987) Perugia

Ancient History: Main Page Municipium of Asisium Quinqueviri and Seviri

Return to the home page on History

Return to the home page on Assisi