Umbri

The only indication that Umbrian people inhabited the area is in the form of a number of votive bronzes (late 6th - early 4th century BC), which were found in the 19th century. The precise location of the find, which was presumably an Umbrian cult site, is unknown. The surviving bronzes form part of the Bellucci Collection in the Museo Archeologico, Perugia.

Romans and Etruscans

Vettona later benefited from the extension of Via Amerina from Ameria (Amelia) to Perusia (Perugia). Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 121) pointed out that the extension of this road must have pre-dated the early 3rd century BC, when Porta Marzia was built at Perusia to monumentalise its entrance into that city. He suggested that its extension might well have been associated with the conquest of the ager Gallicus by Manius Curius Dentatus in 283 BC: a branch from Perusia to Iguvium would have constituted the most convenient way of reaching the Adriatic from Rome before the construction of Via Flaminia in 220 BC.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 215 and Table 18, p. 224) suggested that Manius Curius Dentatus probably settled veterans assigned to the Clustumina tribe in the territories of Ameria, Tuder and Vettona at around the time of the extension of Via Ameria. This could account for the fact that all three municipia were assigned to this tribe when they received citizenship after the Social War (90 BC). However, it is important to note that Arna (modern Civitella d’Arna), which is near Vettona but more remote from the Via Amerina (see the map above), was also assigned to the Clustumina. Furthermore, both were administered by duoviri in the imperial period (see CIL XI 5614 for Arna and below for Vettona). In this respect, as Lorena Rosi Bonci and Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, at p. 206) pointed out:

-

“Arna and Vettona followed the same path as Perusia: ... the latter was ‘restored’ by Augustus and converted into a municipality administered by duoviri [in the early 1st century AD]” (my translation) .

The full significance of this is discussed below. For the moment, we might note the obvious conclusion, as articulated, for example, byEnrico Zuddas (referenced below, in publication)::

-

“... [Arna and Vettona] must have acquired administrative autonomy only after the war in Perusia [41-40 BC]”.

In other words, they probably belonged to Perusia before the Social War and were probably both assigned to the Clustumina only when they became independent centres administered by duoviri. If so, there is no particular reason to believe that the Clustumina was chosen for these centres because of the presence at Vettona of citizens with this tribal assignation that had first settled there in the late 3rd century BC.

There are no surviving Roman remains within the walls of Vettona, which suggests that it was much less important than (for example) Bevagna, Assisi and Spello in Roman times. It seems to have been an Etruscan, rather than an Umbrian, settlement (despite its position on the east bank of the Tiber):

-

✴Two ancient cippi (late 3rd or early 2nd century BC) from Bettona relate to a “tular”, an Etruscan word for boundary.

-

✴The (admittedly few) surviving pre-Latin funerary inscriptions from Bettona commemorate people with Etruscan names.

-

✴Some 200 architectural terracottas (mostly 3rd-2nd centuries BC) from a temple that was on an unknown site near Bettona display Etruscan rather than Roman influence. (Some of them came from a later period, which suggests that the temple underwent extensive renovation after the Social Wars).

In particular, Vettona seems to have had close links with Etruscan Perusia:

-

✴Its first walls (3rd century BC) have much in common with those of Perusia, and might have formed part of an outer defensive ring that protected that city.

-

✴The broadly contemporary Ipogeo di Colle, northwest of modern Bettona, has much in common with the larger Ipogeo di San Manno, outside Perugia.

A large proportion of the surviving or recorded funerary inscriptions from Bettona (including two from the Ipogeo di Colle) are in archaic Latin and presumably date from the 2nd century BC. The reason for this precocious use of Latin at Bettona is unclear.

Vettona After the Social War (ca. 90 BC)

According to Lorena Rosi Bonci and Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, at p. 206):

-

“Arna [now Civitella d’Arna] and Vettona followed the same path as Perugia:

-

when the latter was ‘restored’ by Augustus and converted into a municipality administered by duoviri [in the early 1st century AD].

-

... [Arna and Vettona were also] instituted as autonomous municipalities that ... received ... duoviri [a evidenced by two inscriptions commemorating Sextus Valerius Proculus in the early 1st century AD - see below]. In the previous period, it must therefore be assumed that both Vettona and Arna had been administratively dependent on Perugia: such outposts on the left bank of the Tiber [would have given Perusia] full control of the river valley” (my translation) .

After the fall of Perusia in 40 BC, its territory beyond a Roman mile from the city walls was confiscated. It seems to me that is most unlikely that Perusia retained control over either Arna or Vettona from this point. Unfortunately, there is no way of knowing how these two centres were administered prior to the establishment of the duovirate, probably in the early 1st century AD (see below).

Octavian seems to have assigned some of what had been Perusine territory near Vettona for veteran settlement: this is suggested by two inscriptions from the town or its surrounding area that commemorate members of the Lemonia tribe, which was the tribal assignation of the nearby colony of Hispellum (Spello):

-

✴CIL XI 5195, from an unknown location at Bettona, which is now embedded in the Palazzo del Podestà:

-

L(ucius) Marius C(ai) f(ilius)/ [Le]monia; and

-

✴CIL XI 5551, from Torgiano, which is now in the Monastero di Sant’ Erminio, Perugia:

-

Sex(to) Turṛ[eno?]/ Sex(ti) f(ilio) Lem(onia)

According to Enrico Zuddas and Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, at p. 61)

-

“For both inscriptions, which are united by type [they are funerary inscriptions of similar type], onomastics [the form used for the names] and paleography [the characteristics of the script] (and therefore both datable to the end of the first century BC), it can be assumed that the deceased was a veteran [settled on land that now belonged to Hispellum]” (my translation).

If so, then these would have been veterans whom Octavian had settled at the colony at Hispellum, probably in a second wave of settlement there after the Battle of Actium (31 BC).

Sextus Valerius Proculus (early 1st century AD)

As noted above, Vettona was established as an independent municipium administered by duoviri, probably in the early 1st century AD. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2009, at p. 67) suggested that:

-

“... part of [what had been Perusine] territory - almost entirely confiscated [in 40 BC] - will have been be used to support new municipal entities [of Vettona and Arna]” (my translation).

Only a single duovir of Vettona is known: two inscriptions from Vettona commemorate a duovir called Sextus Valerius Proculus, who belonged to the Clustumina, the voting tribe to which Vettona was assigned:

-

✴An inscription (CIL XI 7979), which was discovered in the Ipogeo di Colle, Bettona, is now in the deposit of the Museo Archeologico, Perugia). It reads:

-

SEX- VALERIVS SEX--

-

F- CLV- PROCVLVS

-

PR- ETRVRIAE

-

II- VIR

-

It commemorates Sextus Valerius Proculus, son of Sextus, who had been a duovir and praetor Etruriae.

-

✴Sextus Valerius Proculus was also one of two members of the member of the Sexti Valerii family commemorated on the plinth of a funerary monument, that was discovered in 1996 in Via della Sorgente, Bettona (now in the Museo Archeologico, Perugia). Each of the commemorative inscriptions on the plinth recorded that the decurioni (magistrates of the municipium) had paid for the funeral of the man commemorated. The inscription relating to Sextus Valerius Proculus (AE 1996, 653b) reads:

-

SEX. VALERIO SEX. F. CLV. / PROCVLO

-

IIVIRO PONTIFICI/ PR. ETRVRIAE

-

FVNVS ET LOCVS SEPVLTV

-

RAE D.D. PVBLIC. DATVS

-

It records his positions as duovir and and praetor Etruriae (as in the inscription above) as well as that of pontifex (municipal priest of the imperial cult).

The EAGLE database (see the CIL/AE links above) dates both of these inscriptions to the first three decades of the 1st century AD.

Sextus Valerius Proculus is the earliest known holder of the post of praetor Etruriae, which was probably the annually elected priest who presided over festivals of the Etruscan Federation, which had been revived, probably by the Emperor Augustus. Sextus Valerius Proculus could have represented Perusia in this federation: however, the fact that another holder of this post was commemorated in Vettona in the 4th century (see below) suggests that Bettona was regarded as an Etruscan city, at least in this context.

Anonymous Quattuorvir (2nd century AD)

This fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 5181), which was re-used at San Quirico and which is now in the deposit of the Museo Civico, records a now-anonymous quatuorvir iure dicundo. According to Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. ??), it is on a block that was reworked to serve as a fountain. Its original location is unknown. However, Enrico Zuddas (as above) suggested that:

-

“... ... rather than attesting to a constitutional change [from a duovirate to a quatturvirate at Vettona], it should be re-assigned to Urvinum Hortense [modern Collemancio, some 11 km south of Bettona]. Materials from several centres have been reused in the church of San Quirico (which is where it was found and which now belongs to Bettona), most of them (CIL XI 5168, 5191 and probably also 5166 and 5197 ) ... from Urvinum Hortense and one certainly from Asisium (CIL XI 5391 ...): none [of them can be securely assigned to] Vettona” (my translation).

Maria Bonamente (referenced below, at p. 201, note 29) noted that quattuorviri are also recorded in CIL XI 5175 and CIL XI 5178, both of which are from Urvinum Hortense.

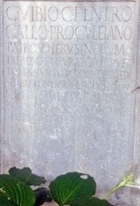

Caius Vibius Gallus Proculeianus (205 AD)

C. Vibio C.f. L.n. Tro(mentina)

Gallo Proculeiano

patrono Perusinorum

patrono et curatori r(ei) p(ublicae)

Vet/tonensium, iudici de V dec(uriis)

aedi/li, patrono collegi centon(ariorum)

Vibius Veldumnianus

avo karissimo, ob cuius

dedicationem dedit

decurionibus ((denarios)) II, plebi ((denarium)) I

L(ocus) d(atus) d(ecreto) d(ecurionum)

This inscription commemorates Gaius Vibius Gallus Proculeianus, the great-grandfather of the future Emperor Gallus (251-3). The statue of him that once stood on this base was commissioned by his own “dearest grandfather”, Vibius Veldumnianus. He had been a patron, decurial judge and aedile in Perusia and patron of a guild (perhaps the woolworkers’ guild) there; and also “patronus et curator rei publicae Vettonensium” (defender of the interests of the citizens of Vettona at Rome and treasurer (curator) on behalf of the Roman authorities. The inscription on the side gives the date:

Dedic(ata) idibus Iul(iis)

Imp(eratore) M(arco) Aurelio Antonino Aug(usto) Pio Fel(ice) II

[et P(ublio) Septimio Geta Severo Caes(are) co(n)s(ulibu)s]

That is, 21st July in the year of the second consulate of the Emperor Caracalla (Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Augustus), which he served with his brother Geta (Publius Septimius Geta Augustus) in 205 AD. The last line of the inscription was erased after Geta was murdered in 211.

Anonymous Praetor Etruriae (4th century AD)

A fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 5170) was on a stone that was re-used in the facade of the church of Santa Maria Maggiore, Bettona: it was detached in 1797 and subsequently lost. A surviving transcription indicates that only a fragment from the centre of the original inscription had survived:

...]a Tuscia suam [...

...]avit neq(u)idem ad aliquam q(u)aes[...

...]it ob quem liberalitatem suam etiam [[...

...]in urbe sacra administrans et pro amore civico filios ei[us...

...Di]scolium et Apronianum tabulis aere inciso[s ...

...] plebis civica patronos cooptarunt ex quibus [...

...prae]tore Aetruriae XV p(o)p(ulorum) dedit Discolium et Apronia[num ...

...]m Aetruriae ludos aedidit paradoxis et urbe et div[..

...]os per decen dies aepula ordinibus propîna[t] et ce[nas ...

...]nis diebus dedit et civitatibus ex sen[atus ...

...]otidem et annonas et cum[...

...]us [---]axis[...

The fact that one of the sons of the subject was called Apronianus suggests that he might have belonged to the same family as Lucius Turcius Apronianus, who was Corrector of the Province of Tuscia et Umbria in 342 AD. The inscription records that, because of his love, his sons, Discolius and Apronianus, had become patrons of a city, presumably Vettona. He had held games in Etruria (‘Aetruriae ludos aedidit’), although, as Enrico Zuddas (referenced below as E. Zuddas (b)) pointed out, not necessarily in his capacity as Praetor Etruriae XV Populorum. The inscription is discussed in the context of the Praetores Etruriae in the page on the Revived Etruscan Federation. (Enrico Zuddas (b) reproduced a drawing that was made before it was last as his Figure 3).

Read more:

E. Zuddas (a), “Dal Quattuorvirato al Duovirato: gli Esiti del Bellum Perusinum e i Cambiamenti Costituzionali in Area Umbra”, in

S. Evangelisti and C. Ricci (Eds), “Le Forme Municipali in Italia e nelle Province Occidentali tra o Secoli I AC e III DC: Atti della XXIe Rencontre Franco-Italienne sur l’ Épigraphie du Monde Romain (Campobasso, 24-26 settembre 2015)”, (2017) Bari, at pp. 121-32

E. Zuddas (b), “La Praetura Etruriae Tardoantica”, in

G. A. Cecconi et al. (Eds), “Epigrafia e Società dell’ Etruria Romana (Firenze, 23- 24 ottobre 2015)”, (2017) Rome, pp. 217-35

L. Rosi Bonci and M. C. Spadoni (Eds), “Arna: Supplementa Italica 27”, (2013) Bari

S. Sisani, “Dirimens Tiberis? I confini tra Etruria e Umbria”, in

F. Coarelli and H. Patterson (Eds) “Mercator Placidissimus: the Tiber valley in Antiquity: New Research in the Upper and Middle River Valley”, (2009) Rome

E. Zuddas and M. Spadoni, “La Lemonia nella Valle Umbra”, in

M. Silvestrini (Ed.), “Le Tribù Romane: Atti della XVIe Rencontre sur l’ Épigraphie (Bari 8-10 ottobre 2009”, (2010) Bari

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

M. Bonamente, “Due Sexti Valerii Duoviri di Vettona”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 114 (1996) 197–204

History: Main page Ancient History

Return to the home page on Bettona