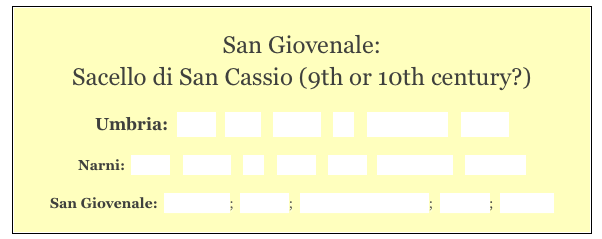

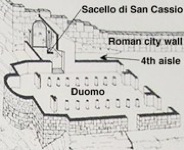

The entrance in the marble screen in the 4th bay of the "new" right aisle of San Giovenale leads to what the remains of the so-called Sacello di San Cassio. (Sacellum is the Latin word for shrine). As illustrated in the diagram above, this shrine was built against the Roman city wall, traces of which can be seen high up to the left.

Original Chapel

According to the legend (BHL 4614) of St Juvenal, which purports to be by his successor, Bishop Maximus , St Juvenal was born in Africa and was appointed as the first bishop of Narni by Pope Damasus I in 369. He performed numerous miracles, winning over 2,000 converts in a single day. He died in ca. 376 and was buried outside the Porta Superiore of Narni, on the Via Flaminia. Bishop Maximus built a chapel near his grave, using money donated by 40 sailors who had been saved in a storm by the intercession of the saint. This chapel was probably the Sacello di San Cassio, which was built against the Roman city wall.

The earliest known version of the legend of St Juvenal was relatively late: it might actually have been written as late as ca. 880,when his stolen relics were returned to Narni (see below). However, Gregory I mentions him in the ‘Dialogues

According to his legend,, the first Bishop of Narni, was buried on this site outside the city walls in ca. 376. His successor, St Maximus built a chapel over the grave, using money donated by 40 sailors who had been saved in a storm by the intercession of the saint. In his “Homiliarum in Evangelia” (2:37), St Gregory records that St Cassius (who was bishop of Narni in the period 536-58) frequently said Mass on the tomb of St Juvenal. There must therefore have been a chapel over this tomb. There is circumstantial evidence (see below) to suggest that it served as a funerary chapel for the bishops of Narni.

Adalbert I, Margrave of Tuscany destroyed this chapel when he sacked Narni in 878, after he had participated in an attack on Rome in an effort to force Pope John VIII to crown Carloman as Holy Roman Emperor. He stole the relics of SS Juvenal and Cassius and those of Fausta, and took them to San Frediano, Lucca. These events are recorded in the account of the life of St Cassius in the “Passionario Lucchese” (12th century): “Sarcofaga rupta sunt, mausolea fracta, corpora sanctorum abstracta sunt, vehicula parata”.

Later Shrine

John VIII lifted the excommunication of Adalbert I in November 880 on condition that he honoured a promise that he had made, and he was given the deadline of the following March. This promise seems to have involved the return of the relics of St Juvenal, but not those of St Cassius, to Narni.

On their return to Narni, the relics of St Juvenal were apparently buried in the rock below a new shrine (now known as the Sacello di San Cassio) that was built close to the site of his original grave. Guerriero Bolli (referenced below) has put forward an interesting hypothesis relating to the construction of the shrine, which he associates with:

-

✴Rotilde da Spoleto, the wife of Adalbert I of Tuscany,

-

✴her grandson, Bishop John of Narni (940-60); and

-

✴his son, also Bishop John of Narni (960-5) and then Pope John XIII (965-72).

The suggestion is that these were all possible sponsors of the project, which might well have extended over a considerable period of time.

This shrine was later integrated as a chapel off the right side of the new Duomo , as illustrated in the diagram above. When Pope Eugenius III consecrated the Duomo in 1145, he also consecrated the “oratorium Sancti Juvenalis”. Most of it was then demolished when the "new" aisle of the church was built in the 14th century: the arch in the colonnade opposite the screen (behind the viewer in the photograph above), which is larger than the others, probably reflects the original entrance to the shrine from the church.

The significance of the shrine was modified in the 17th century:

-

✴The relics of St Juvenal were rediscovered in 1642 and translated by Bishop Gianpaolo Bocciarelli to a new site under the high altar of the Duomo. The empty sandstone sarcophagus (9th century) that had contained them remains in situ (see below).

-

✴The relics of St Cassius were returned from Lucca to Narni and placed under the altar in the shrine in 1679. It was probably at this point that what remained of the shrine became known as the Sacello di San Cassio.

Back Wall of the Shrine

The back wall of the shrine and its (originally subterranean) crypt survive behind the screen. The diagram above, which illustrates the pictorial decoration of the back wall, came from the paper (referenced below) that described the rediscovery of its decoration under plaster in 1953. The upper part can be seen from the nave:

-

✴The mosaic of the Redeemer might be original (albeit much restored). Guerriero Bolli (referenced below) suggests that it could have been a gift from the Empress Theophano, the Byzantine wife of the Emperor Otto II, whom John XIII (previously Bishop of Narni) crowned as empress in 972. Mauro della Valle (also referenced below) proposes a date just prior to 1145, when Eugenius III consecrated the shrine and the Duomo.

-

✴The frescoes to the sides of it, which are later (perhaps dating to the 12th century), depict:

-

•two female saints to the left of the mosaic;

-

•three male saints to the right.

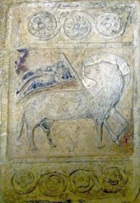

The frescoes below, which are obscured by the marble screen (see below), depict:

-

✴St Juvenal saving the 40 sailors who subsequently financed the chapel that was built over his grave; and

-

✴the desecration of the grave and theft of the relics by Adalbert I.

[The column on the left now has a fresco of St Peter, which was found under an earlier, now detached fresco of St Michael.]

Screen (16th century)

The screen across the entrance to the shrine was constructed in the early 16th century, using architectural fragments from an older structure. The inscription on the architrave above the entrance records that Bishop Pietro Gormaz (1499-1515) commissioned the present arrangement.

-

✴The relief of two lambs and a cross contains an inscription (CIL XI 4164) that marked the grave of St Cassius (“CASSIVS INMERITO”) and his wife Fausta. The relief, which probably came from their monument in the original funerary chapel, was first documented (in its current location) in 1661. The full text reads:

CASSIVS INMERITO PRESUL DE MVNERE CRISTI

HIC SVA RESTIVO TERRAE MIHI CREDITA MEMB[RA]

QVEM FATO ANTICIPANS CONSORS DVLCISSIMA VITAE

ANTE MEVM IN PACEM REQVIESCIT FAVSTA SEPVLCRVM

TV ROGO QVISQVIS ADES PRECE NOS MEMORARE BENIGNA

CVNCTA RECEPTVRVM TE NOSCENS CONGRVA FACTIS

S .D. ANN.XXI. M.VIIII. D.X

R.Q. IN PACE PRID. KAL. IVL P.C. BASILI VC ANN. XVII

-

This records that St Cassius died 17 years after 541, the date at which Basil held office as Consul in Byzantium, on “PRID KAL IVL” - i.e. on 30th June 558. He had held office for almost 22 years. (The use of the Byzantine dating device arose because Narni was in Byzantine hands from 552, when Narses liberated it from Totila).

-

✴The statue (early 14th century) on the left of St Juvenal enthroned seems to have been commissioned for the niche that still contains it. The portal below it used to open onto a staircase leading to a passage to the adjacent Canonica. This part of the screen probably pre-dates the rest of the structure.

-

✴The niche to the right of it is too high for the Pietà (dated by inscription to 1525), and was modified on the left to accommodate the head of Christ.

Surviving Chapel

The chapel as it survives behind the screen is the result of a series of modifications over the centuries. In particular, its pavement is made up of a disorderly compilation of fragments of various ages and from various locations.

An inscription (CIL XI 4163) on the left wall reads:

HIC QUIESCIT PANCRATIUS EPISCOPUS

FIL PANCRATI EPISCOPI

FRATER HERCULI EPISCOPI

DEPOSITUS IIIN OCTOB CONS ALBINI IUNIORIS

It commemorate Bishop Pancratius , the son of another Bishop Pancratius and brother of Bishop Hercules and is dated to the consulate of Flavius Albinus iunior (493 AD). It is possible that the wall in which the inscription is embedded was part of the original funerary chapel built over the tomb of St Juvenal. Alternatively, the inscription might have been recovered after that chapel was destroyed and embedded here when the chapel was rebuilt. It seems never to have been exposed to the elements, and so provides circumstantial evidence for the tradition that the early bishops of Narni were buried in a chapel here.

Until 1661, when the funerary inscription above was probably “rediscovered”, the veneration of St Cassius (and “St” Fausta) had apparently been largely confined to churches associated with the Canons of San Frediano, Lucca. Thus, when Bishop Ottavio Avio requested from the Canons the return of the relics of St Cassius in 1679, he probably used the existence of this inscription as justification.

The relics (which comprised: a small bone in a silver urn; a larger bone; and two sacks containing the ashes of St Cassius) were duly returned and placed below a new altar in the shrine in 1680. The altarpiece was composed of a number of 15th century fragments. It was probably at this point that the shrine became known as the Sacello di San Cassio.

The feast of St Cassius is celebrated in Narni on 13th October, the date of the translation of his relics to Narni.

Sarcophagus of St Juvenal (ca. 600 AD)

The opening in the wall to the left of the altar leads to the steps down to a chamber cut out of the rock. The relics of St Juvenal were hidden here from ca. 880, when they were returned from Lucca, until 1642, when they were rediscovered and subsequently moved to the crypt. The empty sandstone sarcophagus remains in situ. It belongs to a group that seems to have been manufactured in Spoleto in the 5th century, two of which are known housed the relics of bishop saints: this one at Narni and the sarcophagus of St Felix, which is now in the Abbazia di San Felice di Giano. The sarcophagi are all characterised by a low relief on one side that consists of a rectangle flanked by two triangles and then by two arches with architraves. A wide variety of dates has been proposed for this group of sarcophagi: that suggested here was suggested by Mario Sensi (referenced below, at p. 90):

-

“The sarcophagus at Foligno which was contemporary with those from Giano, Narni and Spoleto, is assignable on the basis of [the shared] decorative motif to the 6th or 7th century” (my translation).

The damaged fresco inside, on the bottom of the sarcophagus, was probably originally an effigy of St Juvenal.