Blessed Giles

The church and convent stand on the site of the hermitage on Monteripido in which the Blessed Giles lived for some 30 years. [It is in theory possible to visit this hermitage, which survives in the grounds of the convent, but I have never managed it.] When the Blessed Giles died here in 1262, his body was taken to San Francesco al Prato and placed in a Roman sarcophagus that was found nearby.

According to tradition, the so-called Altarpiece of the Blessed Giles (ca. 1439 - see below) was painted for the shrine of the Blessed Giles in San Francesco al Prato on the wooden panel upon which Giles’ body had been carried to this church from his hermitage. (The later history of his cult is set out on this page on San Francesco al Prato. As described in more detail there, the relics and the sarcophagus are now in the Oratorio di San Bernardino).

History of the Convent

The land here belonged to the Coppoli family until 1276, when Giacomo di Boncorte Coppoli gave it to the friars of San Francesco al Prato. A convent here was documented in 1290 and a church in 1310.

In 1374, the Blessed Paoluccio Trinci came to Perugia and defeated a group of dissident Franciscans in an open debate. In response, the Franciscan Minister General transferred the Convento di Monteripido to the new Observant wing of the order that Paoluccio Trinci had established.

The convent played host to a series of important Observant Franciscans in the 15th century:

-

✴St Bernardino of Siena established a Studium Generale here in 1438;

-

✴St John of Capestrano served his novitiate here;

-

✴St James of the Marches lectured here; and

-

✴Brothers Barnaba Manassei, Michele Carcano, Fortunato Coppoli (from the family who had donated the land to the Franciscans) and the Blessed Bernardino da Feltre conceived the idea of the Monti di Pietà here in 1462.

In 1455, Pope Callistus V subjected the nuns of Sant’ Antonio da Padova to the authority of the friars of Monteripido. This association must have become more important to the nuns in 1461, when the congregation to which they had belonged was dissolved. However, the first sign of controversy about the vexed issue of clausura emerged at this time: in a bull somewhat optimistically beginning: “Ut toletur discursus” (In order to settle the debate), Pope Pius II ruled that the sisters were not obliged to cut themselves off from the community. Despite this support, the friars threatened to withdraw their spiritual support from them in 1469, and were only dissuaded when the Commune insisted that “the imperious friars had brought shock and scandal to the city” in attacking the traditions of a fine institution so “close to the heart of the citizens”. The issue boiled up again in 1482, when Pope Sixtus IV granted the friars’ request that they should be allowed to withdraw their spiritual guidance from the sisters of both Sant’ Antonio and Sant' Agnese because the sisters’ persistence. They reacted by holding two identical open chapter meetings, and sent notarised minutes of their public arguments on the matter to Sixtus IV. He rapidly moved to diffuse the issue by placing the sisters under the spiritual guidance to the newly-arrived Amadeiti Fathers at San Girolamo.

The friars of Monteripido also provided spiritual guidance for the nuns of Santa Maria di Monteluce for much of the 15th and 16th centuries. They also encouraged the nuns to set up their scriptorium in 1448. The “Memoriale di Santa Maria di Monteluce” records that, when the nuns decided to commission a new altarpiece for the high altar of their church in 1503, they asked the friars to recommend “il maestro il migliore” (the finest master) from whom they might commission it, and the friars recommended Raphael. Thus it was that he was commissioned to paint the Monteluce Altarpiece (1505-25).

In 1642, Pope Urban VIII planned to fortify the convent during the War of Castro. A small part of these fortifications survives. Fortunately, the work was stopped when he died two years later. (As noted below), the foundations for part of the fortress were used for the new library in 1754).

The friars were expelled in 1810 but were able to return in 1815. The 15th century church was modified and extended in 1858-60. However, the convent was suppressed again in 1860 and the few friars who had managed to remain were expelled in 1865. The contents of the library were confiscated and the complex was put to military use. The Franciscans were able to buy back the church and convent in 1874.

Approach

Convent

The path leads to an enclosed courtyard, with the church ahead, the library to the left and the entrance to the first cloister of the convent to the right. The second and third cloisters are beyond it.

This courtyard contained two chapels that were demolished in the 18th century when the library was built (see below). One of these was the Cappella della Natività, which apparently once had the arms of the Ercolani family of Panicale sculpted in relief on one of its pilasters. The frescoes that were detached at this time were attributed to Perugino: one of them survives in the Galleria Nazionale (see Art from the Complex, below).

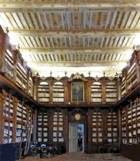

Library (1754-72)

The library of the convent developed over a long period from 1438, when St Bernardino of Siena established a Studium Generale here. By 1723, its catalogue contained some 4,000 books, but the friars were running out of room in which to store them.

-

✴Paolo Brizi apparently decorated the beamed and brick ceiling in 1773. (It was probably while working here that Brizi contracted the malaria that was to prove fatal).

-

✴The fine walnut bookshelves were installed in 1779.

Second Cloister

The structure of this cloister largely survives from the 15th century.

Frescoes (17th century)

These three frescoes in lunettes along the east side of the cloister, which are attributed to Antonio Maria Fabrizi, depict (from the left):

-

✴St Francis speaking to a knight (perhaps Count Orlando di Chiusi, who gave Mount Alvernia to the Franciscans);

-

✴St Francis’ vision of the Madonna and Child, in which she offers the baby Jesus to him; and

-

✴a friar places his foot on the chest of St Francis, who is prostrated by demonic images (an incident that happened at San Pietro a Bovara).

Each of the three is decorated with the arms of its donor.

Frescoes (17th century)

These four frescoes in lunettes along the west side of the cloister, one of which was apparently signed by Giovanni Domenico Mattei of Foligno, depict (from the left):

-

✴St Antony of Padua saves a child who has fallen into the fire (illustrated here);

-

✴St Francis and the wolf of Gubbio;

-

✴St Francis emerges triumphantly from Purgatory; and

-

✴St Francis throws himself on a fire to avoid the temptation offered by a semi-naked woman sent by the Sultan.

Each of the three is decorated with the arms of its donor.

Church

As noted above, the 15th century church was modified and extended in 1858-60. The apse and the vaulting of the nave of the original church survive, together with the chapel on the left, which had been added in 1588.

The choir stalls (1571-81) were moved here from the Oratorio di San Domenico in 1863.

Crucifix (16th century)

Cappella dell’ Immaculata (1588)

Triptych (1923)

This triptych by Gerardo Dottori, which the artist which he gave to the friars in 1971, is on the right wall. The panels depict:

-

✴St Francis and the wolf of Gubbio;

-

✴the death of St Francis; and

-

✴St Francis preaching to the birds.

Art from the Church

Dossal (early 14th century)

Two panels from what was originally a double-sided dossal entered the Galleria Nazionale from the Convento di Sant’ Antonio di Padova, Paciano Vecchio, outside Perugia in 1872. They are dated on stylistic grounds to the early 14th century and are the autograph works of the so-called Maestro di Paciano.

I In fact, the Convento di Sant’ Antonio did not exist until 1496, so it was clearly not the original location of the dossal. It is possible that it was originally commissioned for the Convento di Monteripido, which, like Sant' Antonio, belonged to the Observant Franciscans. The friars of Monteripido commissioned another double-sided altarpiece of similar width in 1502 (see the Monteripido Altarpiece - Room 23); they may have passed their original altarpiece to Sant' Antonio at that point.

The front of the dossal depicts the Madonna and Child enthroned with angels. Unusually, the baby Jesus wears a triple-knotted cord around His waist, a reference to the Franciscan habit. Two figures kneel before the throne:

-

✴a layman, presumably the donor, on the left; and

-

✴a Franciscan on the right. He wears a patched cloak over his habit and has a rayonant halo that suggests that he has been beatified. If the hypothesis as to the original location of the dossal is correct, this figure is almost certainly the Blessed Giles, the early Franciscan who lived on the site of the later Convento di Monteripido.

Four saints occupy fictive aedicules to each side:

-

✴on the left:

-

•St Michael Archangel (perhaps because Monteripido is just outside Porta Sant' Angelo);

-

•St Clare;

-

•St Francis (who holds a text that refers to his stigmatisation); and

-

•St Peter; and

-

✴on the right:

-

•St Paul;

-

•St Louis of Toulouse;

-

•St Antony of Padua; and

-

•St Mary Magdalene (represented as a hermit, clothed only in her long hair).

The back of the dossal, which is damaged, originally depicted five scenes from the Passion. The central one, which was almost certainly a Crucifixion, has been completely lost.

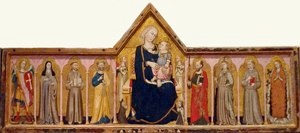

Altarpiece of the Blessed Giles (ca. 1439)

This altarpiece, which is attributed to Mariano di Antonio, was commissioned in ca. 1439 for the new altar of the shrine of the Blessed Giles in San Francesco al Prato. According to tradition, it was painted on the wooden panel upon which Giles’ body had been carried for burial from his hermitage on the site that later became the Convento di Monteripido to San Francesco al Prato.

The altarpiece was replaced on the altar and moved to the sacristy in ca. 1513. It was removed from the church in 1863, and was already damaged when it entered the Galleria Nazionale in 1872. It suffered further during its stay in the Convento di Monteripido in the period 1923-54.

The altarpiece depicts the Blessed Giles standing in a fictive aedicule, with three scenes from his life and posthumous miracles to each side. This format was consciously archaic and based on that of a number of panels that had been produced in the 13th century to celebrate the canonisation of St Francis. One of the better-preserved narrative scenes, which depicts a miracle occurring beside the sarcophagus shortly after Giles had died, is important for our understanding of the original arrangement of the cult site.

Candlesticks (ca. 1500)

St Francis receives the stigmata (ca. 1500)

This fresco, which was detached from the facade of the church in 1858 and moved to the Galleria Nazionale in 1863, is attributed to Giovanni di Pietro, lo Spagna. It depicts St Francis kneeling in a landscape as a seraph nailed to a Cross appears to him in the sky above. To the right, two of his companions obliviously continue reading.

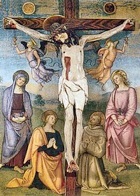

Monteripido Altarpiece (1502)

In 1502, the friars used money that had been left to them in a will some five decades earlier to commission this double-sided altarpiece from Perugino. It probably replaced another double-sided altarpiece (early 14th century) of similar width that was subsequently recorded in the Convento di Sant’ Antonio di Padova, Paciano Vecchio, outside Perugia (now in the Galleria Nazionale - Room 4).

-

✴On the side facing the friars in the choir, mourning figures of the Virgin, SS Mary Magdalene, John the Evangelist and Francis and angels were painted to form the backdrop to the polychrome wooden Crucifix (ca. 1460) attributed to Giovanni Tedesco that already decorated the high altar.

-

✴On the side facing the congregation, the Apostles witness the Coronation of the Virgin, which takes place in a mandorla supported by angels. (The friars specified the enthroned Christ and the Virgin with four saints below: the final composition reflected that of the Coronation of the Virgin (1486) that Domenico Ghirlandaio had painted for the high altar of the church of another Observant Franciscan convent, San Girolamo, Narni.

-

✴There was also a predella, subsequently lost, that included representations of SS Bernardino da Siena and Bernardino da Feltre.

It is sometimes argued that Perugino would have been unable to complete the commission quickly, since he was away from Perugia in late 1502 and for most of 1503. However, Raphael used parts of the composition of the backdrop to the Crucifix for his altarpiece (1503) of the Crucifixion with Saints (Mond Crucifixion) in San Domenico, Città di Castello. This suggests that the Monteripido Altarpiece was at least designed by 1503 and that its execution might have been largely delegated to the workshop.

Agostino Tofanelli selected the altarpiece for the Musei Capitolini, Rome in 1812. It was returned to Perugia in 1817 and ceremonially translated to its original position on the high altar in 1822. It entered the Galleria Nazionale in 1863 and was restored in 1994.

Adoration of the Shepherds (ca. 1504)

The Ercolani family probably commissioned the three frescoes that were recorded in the lunettes in walls of the Cappella della Natività. These frescoes, which were attributed to Perugino, depicted:

-

✴the announcement to the shepherds of the birth of Christ;

-

✴the Adoration of the Shepherds (above the altar); and

-

✴the Adoration of the Magi.

The frescoes were recorded in 1674, by which time they were badly damaged. Those on the side walls were subsequently lost. The fresco of the Adoration of the Shepherds was detached in 1856 and is now in the Galleria Nazionale. It was restored as far as possible in 1994.

In this fresco, the baby Jesus lies on the ground, adored by the Virgin and St Joseph and four kneeling shepherds. The composition of this surviving fresco is related to two other frescoes of this subject:

-

✴the fresco (1496-1500) in the Collegio del Cambio; and

-

✴the fresco (1503) in San Francesco, Montefalco.

It was probably painted shortly afterwards.

Madonna and Child with saints (1518)

According to the inscriptions, Luca Alberto Podiani commissioned this altarpiece in 1518 from Sinibaldo Ibi. [Luca Alberto Podiani (1474-1551) was a celebrated doctor and scholar, rector of the Sapienza Vecchia in the period 1504-20.] It depicts the Madonna and Child enthroned with SS Francis and Leonard. Two flying angels above who hold a crown above the head of the Madonna.

The altarpiece entered the Accademia di Belle Arti in 1810 and is now in the Galleria Nazionale. There are at least two possibilities for its original location:

-

✴the Convento di Monteripido, where, according to his will of 1548, Luca wished to be buried; or

-

✴Sant’ Agostino, where Luca was actually buried in 1555, in his family chapel.

Madonna and Child with saints (ca. 1518)

This altarpiece was recorded in the 18th century in the sacristy of the Convento di Monteripido, and passed to the Galleria Nazionale in 1863. It depicts the Madonna and Child enthroned in a landscape, flanked by the kneeling SS James and Francis. Two flying angels hold a crown above the head of the Madonna.

This panel seems to have been the object of a dispute between Friar Pietro da Castello and Perugino that was settled in 1518. It seems that, although Perugino had received the commission, the panel was actually painted by another artist. Laura Teza , who published the relevant document (reference in the page on the artist), attributes it to Berto di Giovanni.

St Didacus (Diego) of Alcalá (ca. 1600)

This panel from Monteripido, which is signed by Simeone Ciburri, is now in the deposit of the Galleria Nazionale. It depicts the standing figure of St Diego of Alcalá carrying a cross and flanked by the Blessed Antony of Stroncone and the Blessed John of Stroncone. Personifications of the Virtues of Humility, Purity and Patience are depicted above. It is illustrated in the website of Musei d’ Italia.