Conquest

From the Conquest of Veii (437 - 396 BC) to the

to the Sack of Rome (390 BC)

Conquest

From the Conquest of Veii (437 - 396 BC) to the

to the Sack of Rome (390 BC)

Roman and Southern Etruria

From at least the 6th century BC, Veii, the most southerly of the major Etruscan city-states, seems to have been among the most prosperous of them, with an extensive and well-developed territory that extended southwards towards the Tiber. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 347) observed that, early its its history, Rome was:

“... dominated by Etruscan influence and culture, and her relationship with Veii must have been particularly close. However, because both cities wished to control the trade route up the Tiber, they clashed often in the 5th century BC.”

Alexandre Grandazzi (referenced below, at p. 76) argued that it is:

“... very tempting to explain the incessant wars that Rome waged against Veii [throughout the 5th century BC] ... as at least in part a struggle for control of the ... salt fields at the mouth of the Tiber], which were, for the most part, located on the [Etruscan] side of the river ...”

This must at least partly explain why, as Louise Adams Holland (referenced below, at p. 288) observed, in the Iron Age:

“... [although] communities did not [generally] grow up on the river banks, even where excellent sites were available ... [two] towns along the lower Tiber ... survived [from] the most remote legendary period: ... Rome and Fidenae, both crossing points.”

She also observed (at p. 306) that the river crossing was the critical point on the route from Veii along the Cremera and on to its markets in the hinterland:

“... less because of the break caused by the ferry itself than because the two roads [from Rome] along the Tiber (Via Tiberina and Via Salaria) intersected the Etruscan road where it met the river on each side. Veii, which could see all the Sabine hills spread out across the Tiber, had no view of the approaches to the crossing by those Tiber roads. It was chiefly for this reason that the height of Fidenae, directly opposite the opening of the Cremera valley, was essential to Veii's communications. Observers on] the isolated height that represents the ancient citadel could forewarn the Veientines by signal if people were approaching by water or by land from any direction. ... To Veii, closed in her narrow glen, Fidenae was a prize worth fighting for in times when the bel vedere, still dear to the Italians, was valued for ... reasons [other than] ... aesthetic delight.”

Given the balance of power between Veii and Rome in the 6th century BC, it is almost certain that Fidenae was essentially under Veientine hegemony at that time, whatever claims were made to the contrary by Roman historians. Nevertheless, as we shall see, the Romans advanced inexorably northwards into the Latin territory on along the left bank of the Tiber thereafter, with the ‘Etruscan’ outpost at Fidenae very much ‘in their sights’.

Roman Expansion Northwards (5th century BC)

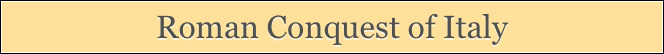

Seventeen Oldest Roman Tribes (G. C. Susini, 1959)

From Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, after p. 354)

The earliest Roman expansion northwards along the Tiber is best hypothesised on the basis of the evidence (such as it is) for the establishment of rural tribes here. The key date is 495 BC, when, according to Livy:

“... Appius Claudius [Sabinus Regillensis] and Publius Servilius [Priscus Structus] were chosen as consuls. ... At Rome, 21 tribes were formed”, (‘History of Rome’, 2: 21: 5-7).

This is usually taken to mean that Livy had a source for the formation of at least one new rural tribe in that year, taking the total number (including the original four urban tribes) to 21: the total was to remain there until 387 BC, when four new rural tribes were established for Roman citizens who were given land that had bee confiscated from Veii after its final defeat. As illustrated in the map above, Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below) argued that, by 495 BC,

✴three rural tribes had been established on the left bank of the Tiber to the north of its confluence with the Anio:

•the Sergia;

•the Claudia; and

•the Clustumina; and

✴the Claudia had been established on the opposite bank of this stretch of the river.

Clustumina

The Clustumina was the only one of the first 17 rustic tribes that was not named for a (presumably prominent) Roman clan:

✴According to Paul the Deacon, in his summary of an entry in the lexicon of the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus:

“Crustumina tribus a Tuscorum urbe Crustumerium dicta est”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 48 L)

“The [Clustumina] tribe is named for the Etruscan town of Crustumerium”, (my translation).

✴According to Livy, in 499 BC:

“... Fidenae was besieged [and] Crustumerium taken ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 2: 19: 1-2).

Jorn Seubers, and Gijs Tol began their report of field surveys carried out in 2011-3 in the ager Crustuminus by observing that:

“The ancient urban centre of Crustumerium was located about 15 km north of Rome and 5 km north of contemporary Fidenae, on a hill overlooking the Tiber valley. The location of the historically attested city was established by archaeological field surveys in the 1970s ... To our current knowledge, the settlement was founded in the 9th century BC and ceased to be an urban centre at the end of the Archaic period, when it fell prey to early Roman expansionism. As such, the probably gradual abandonment of the town in the 5th century BC, which is confirmed by urban surveys, does not conflict with the historical date of its demise in 499 BC.”

Two surviving records, taken together, suggest that the area was under Roman control by 494 BC:

✴according to Livy, in that year, the plebs:

“... withdrew to the mons sacer, which is situated across the river Anio, three miles from Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 2: 32: 2); and

✴according to Varro:

“The Tribuni plebei (tribunes of the plebs) [were so-called] because they were first created from among the military tribunes in the [plebeian] secessione Crustumerina [withdrawal to Crustumerium], for the purpose of defending the [political interests of] plebs”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 6: 18, translated by Roland Kent, referenced below, at p. 79).

It thus seems that the Clustumina was established for Romans settled on land that was confiscated after the fall of Crustumerium: since it was the first of the rural tribes to be named for its location, we might reasonably assume that it was the last of the 17 rural tribes to be founded, and that this occurred in 495 BC. From at least this time, a significant number of Romans would have shared the ager Crustuminus with other Latin and Etruscan communities.

Claudia

Appius Claudius Sabinus Regillensis, the consul of 495 BC was the first securely recorded member of the gens Claudia, for whom the Claudia rural tribe was named. Dionysius of Halicarnassus (ca. 7 BC) recorded a tradition in which, in 504 BC, during a war between the Romans and an alliance of Sabines, Fidenates and Camerians:

“A certain Sabine who lived in a city called Regillum, a man of good family and influential for his wealth, Titus Claudius by name, deserted to [the Romans], bringing with him many kinsmen and friends and a great number of clients, who removed with their whole households, not less than 500 in all who were able to bear arms. ... ; and by adding no small weight to [the Roman] cause, [Claudius] was looked upon as the principal instrument in the success of this war. In consideration of this, the Senate and people enrolled him among the patricians and gave him leave to take as large a portion of the city as he wished for building houses; they also granted to him from the public land the region that lay between Fidenae and Picetia [probably Ficulae], so that he could give allotments [of land] to all his followers. In the course of time, these Sabines were placed in a new tribe, the Claudia, a name which it continued to preserve down to my time”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 5: 40: 3-55):

It is likely that this tradition had grown up to explain the establishment of the Claudia for Roman settlers in the land between Fidenae and Ficulae: this tribe would have existed in 495 BC, and might have been formed in that year and given the name of one of the consuls.

Sergia

Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 40) suggested that:

“The clue to the location [of the Sergia might well lie] in the cognomen Fidenas, which was given to L. Sergius, .... [probably because of his role in 428 BC as a member of] a senatorial commission [sent] to investigate the participation of the Fidenates in [Veientine] raids on Roman territory.”

According to Livy (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 6), the members of this commission were:

✴L. Sergius;

✴Q. Servilius; and

✴Mamercus Aemilius.

In fact, the cognomen Fidenas is only ever associated in the surviving sources with two Roman gens:

✴the Sergii, starting with the L. Sergius C.f. C.n. Fidenas, who served as consul 0r consular tribune on five occasions in in 437 -418 BC (whom Livy believed had been given this cognomen following his part in the war against the Veientines and Fidenates in 437 BC, albeit that our earliest surviving source for his cognomen dates to the entry in the fasti Capitolini for 418 BC; and

✴the Servilii, starting with Q. Servilius P.f. Sp.n. Priscus Fidenas, who served as dictator in 435 and 418 BC, albeit that our earliest surviving source for his cognomen dates to to the entry in the fasti Capitolini for 418 BC.

Thus, the commissioners L. Sergius and Q. Servilius both acquired the cognomen Fidenas at some time before 418 BC. It is possible that each of them acquired this cognomen because of his service as a commissioner to Fidenae in 428 BC. However, pace Ross Taylor, it seems to me to be more likely that each of them acquired it because of his role (or presumed role) in the war of 437-5 BC. That does not necessarily undermine her proposed location for the Sergia:

✴one of the first rural tribes must have been located on the left bank of the Tiber, below the establishment of the Clustumina in 495 BC; and

✴it is entirely possible that it was established for settlers on land here that was controlled by the Sergii.

Ernst Badian (referenced below, at p. 202), in his review of Lily Ross Taylor’s book, commented that:

“... on [the location of the] Sergia, she well may be [right: in any case] we can do no better.”

Fabia

As Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at p. 195) pointed out:

“During each of the seven years 485-79 BC, one of the two consuls was a Fabius. Such domination of the consulship by a single family is unparalleled in the consular fasti of the Republic.”

All of these Fabian consuls had the name cognomen Vibulanus, which probably indicated their now-unknown place of origin.

Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 41) suggested that:

“The Fabia tribe [probably embraced] the land [occupied by] the Fabii and their clients [in the 5th century BC] ...”

The clue to its location probably lies in the tradition that (see Livy, ‘History of Rome’, 2: 48-50), in 479 BC, the Fabii had taken responsibility for a war with Veii that had culminated in a disastrous ambush at the river Cremera two years later in which almost all of them were killed. It is likely that this tradition had grown up to explain:

✴the pattern of Fabian consulates, in which the seven in 485-79 BC was followed by an absence until the consulship of Quintus Fabius Vibulanus in 467 BC; and

✴the location of the Claudia tribe adjoining the territory of Veii south of the Cremera.

Conclusions: Roman Expansion Northwards in the 5th Century BC

It seems from this body of evidence that, throughout 495-387 BC, large tracts of land on the left bank of the Tiber, north of its confluence with the Anio, was settled (albeit not exclusively) by Romans assigned to the Clustumina, Claudia and (possibly) Sergia tribes. However, the Romans seem to have been less successful in expanding on the opposite bank, due to the resistance of Veii. On the other hand, Veii would presumably have faced problems in maintaining commercial links with the markets of central Italy for salt and other products, once the Romans were able to settle a swathe of land around the Tiber crossing at Fidenae.

Fall of Fidenae (438 - 426 BC)

Fidenae

As we saw above, Dionysius of Halicarnassus recorded a tradition in which, during a war between the Romans and an alliance of Sabines, Fidenates and Camerians: in 504 BC, the Sabine Titus Claudius defected to the Romans and, after the Romans’ victory, was rewarded with land for his clients between Fidenae and (probably Ficulae). This might well have been a traditional explanation of the fact that a swathe of land here had been settled by Romans assigned to the Claudia tribe by 495 BC. Support for this hypothesis exists in the form of an inscription (CIL I2 1709), which records a ‘dictator Fidenis’ who belonged to the Claudia, thus suggesting that Fidenae was assigned to the Claudia after its incorporation into the Roman state. Edward Bispham (referenced below, at pp. 380-1), who suggested that this incorporation occurred in ca. 60 BC observed that, before this time, Fidenae had:

“... enjoyed no corporate existence [within the Roman state] since the 4th century BC.”

Dionysius recorded the first Roman confiscation of land at Fidenae itself: in his account, the city fell to the Romans in 504 BC, after which, the Romans caught and executed the leading Fidenates but allowed the rest of the community:

“... to live in the city as before, though they left a garrison ... to live in their midst; and, taking away part of their land, they gave it to this garrison”, ( ‘Roman Antiquities’, 5: 43: 2).

According to Livy, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 17: 1-6), the Romans sent four legati (Caius Fulcinius; Cloelius Tullus; Spurius Antius; and Lucius Roscius), to Fidenae, a putative colonia Romana in 438 BC, to find out why it had defected to Lars Tolumnius, king of Veii. They were murdered there on the orders of Tolumnius, causing huge outrage at Rome. Their statues were erected on the Rostra in the Forum. However, it is by no means clear that Fidenae was a Roman colony at this point, and Robert Ogilvie (referenced below, at p. 284) argued that:

“This ... looks like special pleading. It would be galling to Roman pride to accept that a town so small and so near should have retained its independence so long. Rome's subsequent atrocities against her could be sententiously justified if Fidenae were pictured as a disloyal colony.”

It seems much more likely that, although Fidenae was almost surrounded by Roman territory by 438 BC, it retained its nominal independence under the hegemony of Veii.

We saw above that, according to Livy (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 5-7), the Romans sent three commissioners to Fidenae in 428 BC, apparently in order to investigate the participation of some Fidenates in Veientine raids on Roman territory. As a result of their investigations:

✴those Fidenates who could not explain why they had been away from Fidenae during the time of the raids were banished to Ostia [why Ostia ??]; and

✴a number of new Roman settlers were added to the putative colony at Fidenae, and they were given land that had belonged to men who had fallen in the war of 437-5 BC.

If Fidenae itself was not a colony at this time, then the ‘Fidentaes’ whom the Romans punished would have been settled on nearby land that was under Roman control. Robert Ogilvie (referenced below, at p. 583) suggested that:

“... the iiiviri, Sergius, Servilius, and Aemilius [might have been] ... iiiviri coloniae deducendae, [particularly since] they included one consular in L. Sergius. It would be a typical misinterpretation of the Annales.”

Monica Chiabà (referenced below, at p. 90 and note 155) argued that this is highly probable. In other words, it is likely that the Romans attempted to found a colony at Fidenae in 428 BC, perhaps on land that they already controlled but more probably on land that they had seized from the Fidenates in 435 BC.

Whatever measures were taken in the light of the commissioners’ report from Fidenae, they did not include direct action against Veii: Livy explained that the Romans now faced a period of drought, and any thought of revenge for the Veientine raids had to be postponed. In fact, the Veintines amde a pre-emptive raid in 426 BC and, after their initial success, the Fidenates decided to take part in the war. However, before joining the Veientines:

“... as though they thought it impious to begin war otherwise than with a crime, they stained their weapons with the blood of the new colonists, as they had previously with the blood of the Roman legates [of 438 BC] ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 31: 8).

As we shall see, in a campaign of only 16 days, the dictator Mamercus Aemilius Mamercinus (the third of the commissioners of 428 BC) drove the enemy back into Fidenae and then captured and destroyed the city. Varro noted its existence at the time of the Gallic sack of Rome (traditionally 389 BC):

“The [festival known as the] Poplifugia seems to have been named from the fact that, on this day, the people suddenly fled in noisy confusion: for this day is not much after the departure of the Gauls from the City and the peoples who were then near the City, such as the Ficuleans and Fidenians and other neighbours, united against us”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 6: 18, translated by Roland Kent, at p. 191).

As Bispham observed (above), it seems to have descended into obscurity thereafter, albeit that it was incorporated as a municipium with duoviri in ca. 60 BC.

Livy’s Account of the Fall of Fidenae (438 - 426 BC)

Livy’s is the only surviving narrative account of the Romans’ war with Veii that began with the murder of four Roman legati at Fidenae in 438 BC and culminated in the fall of Fidenae in 426 BC. In this section, I summarise Livy’s chronology.

Phase I (438 - 435 BC)

438 BC: (‘History of Rome’, 4: 17: 1-6)

The Romans sent four legati (Caius Fulcinius; Cloelius Tullus; Spurius Antius; and Lucius Roscius), to Fidenae, a putative colonia Romana, to find out why it had defected to Lars Tolumnius, king of Veii. They were murdered there on the orders of Tolumnius, causing huge outrage at Rome. Their statues were erected on the Rostra in the Forum.

437 BC: (‘History of Rome’, 4: 17: 8 - 20:4)

Tolumnius then led an army of Veientines and Fidenates across the Anio and marched on Rome:

✴L. Sergius, one of the serving consuls, checked his advance, but at great cost in Roman lives.

✴Mamercus Aemilius Mamercinus was appointed to his first dictatorship: he appointed L. Quinctius Cincinnatus as his master of the horse. Mamercinus drove the Veientine and Fidenate armies back across the Anio and to the walls of Fidenae, where they were joined by a contingent from Falerii. In the battle that followed, Aulus Cornelius Cossus, a military tribune, spotted Tolumnius causing mayhem, killed him with his own hands, and stripped him of his armour. This decided the outcome, and Mamercinus duly led his army to victory. Mamercinus was awarded a triumph and dedicated a golden crown to Jupiter in the Capitoline temple. During the triumphal procession, all eyes turned to Cossus: the soldiers sang rude songs in his honour (as they usually did to the triumphant commander) and placed him on a level with Romulus, and he became the first man after Romulus to dedicate spolia opima at the temple of Jupiter Feretrius.

However, the war continued for another two years.

Digression: (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 4-11)

At this point. Livy embarked on an important digression on the existence of other evidence that placed Cossus’ achievement at a later point in his career. I discuss this other evidence in the following section.

436 BC: (‘History of Rome’, 4: 21: 1-2)

The consuls M. Cornelius Maluginensis and L. Papirius Crassus raided the territory of the Veientines and the Faliscans, but they were unable to blockade any of their strongholds because of an epidemic at Rome.

435 BC: (‘History of Rome’, 4: 21: 6 - 22: 6)

Since the epidemic at Rome continued, the Veientines and Fidenates took the opportunity to cross the Anio again and, this time, managed to advance and display their standards not far from the Colline gate. (Livy recorded at 4: 21: 8 and 4: 23: 4 that the Faliscans declined to join the hostilities of this year). Q. Servilius was appointed as as dictator, and he appointed Postumius Aebutius Helva as his master of horse. Servilius mustered an army outside the Colline gate and caught up with the retreating enemy army near Nomentum. The Romans had the better of the fighting, and the enemy army fled to Fidenae. Servilius ordered his men to dig a tunnel from the Roman camp that gave them access to the city. Livy’s last sentence in this account is something of an anti-climax:

“ Whilst the attention of the [enemy] was being diverted from their real danger by feigned attacks, the shouts of the [Romans] above their heads showed them that the city was taken”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 22: 6).

At this point, Livy did not record how the hostilities ended. However, when the Romans decided to declare war on Veii in 427 BC (below), he explained that fetial priests had first to be sent in order to seek reparations, since this earlier war had ended by indutia (a truce), albeit that it had just run out.

Interwar Period (434 - 427 BC)

434 BC: (‘History of Rome’, 4: 23: 3 - 24: 2)

After the Romans’ capture of Fidenae, the Veientines and the Faliscans sent envoys to a meeting of the national council of Etruria at the fanum Voltumnae: this is the first time that Livy identified the national shrine of the Etruscans as the fanum Voltumnae (shrine of Voltumna). In response, Mamercus Aemilius Mamercinus was appointed to his second dictatorship, and he appointed Aulus Postumius Tubertus as his master of the horse. However, the other Etruscans refused to intervene and the threat disappeared. Mamercinus therefore resigned his office.

432 BC: (‘History of Rome’, 4: 25: 6-9)

The other members of the national council of Etruria apparently again refused to take action against Rome, despite the protests of the Veientines that the fate that had overtaken Fidenae now awaited them.

428 BC: (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 5-12):

Aulus Cornelius Cossus, the military tribune whom Livy credited with killing Lars Tolumnius in 437 BC, was elected as on of the consuls of 428 BC. The Veientines raided Roman territory, and it was rumoured that some of the Fidenates had taken part. Three commissioners:

✴Lucius Sergius Fidenas, the consul of 437 BC;

✴Quintus Servilius; and

✴Mamercus Aemilius Mamercinus, the dictator of 437 and 434 BC;

were sent to Fidenae investigate the affair. As a result of their investigations:

✴those Fidenates who could not explain why they had been away from Fidenae during the time of the raids were banished to Ostia; and

✴a number of new Roman settlers were added to the putative colony at Fidenae, and they were given land that had belonged to men who had fallen in the earlier war.

427 BC: (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 12-16).

Livy recorded that, even after the end of the drought:

“... a religious scruple prevented the immediate declaration of war and dispatch of armies; they resolved that fetials must first be sent to require restitution”, (4: 30: 13).

Livy then explained why the fetials’ services were needed: as mentioned above, the previous war had ended :

“... by indutia (a truce). Its time had now run out and, in any case, the enemy had begun to fight again before its expiration; nevertheless fetials were sent; yet, when they sought reparation after taking the customary oath, their words were ignored”, (4: 30: 14-16).

Fall of Fidenae (426 BC)

Because of pressure from the plebs, four consular tribunes were elected for 426 BC. War was duly declared, following which

✴three of the consular tribunes marched against Veii; while

✴the fourth, Aulus Cornelius Cossus, was designated as urban prefect, charged with administering and defending Rome.

The conduct of the war was disastrous, and the people:

“... demanded a dictator ... Here too, a religious impediment arose, since only a consul could nominate a dictator. The augurs were consulted and removed the difficulty: [Cossus] nominated Mamercus Aemilius as dictator [for the third time] and he appointed Cossus as his master of horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 31: 4-5).

Mamercinus restored morale by reminding the Romans that he was:

“... the same Mamercus Aemilius who had defeated the combined forces of Veii and Fidenae, supported by the Faliscans, at Nomentum: his master of the horse ... [was] the same Aulus Cornelius who, as military tribune, had killed Lars Tolumnius, king of Veii, in full sight of both armies, and had carried the spolia opima to the temple of Jupiter Feretrius”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 32: 4-5).

Meanwhile, the Fidenates had decided to take part in the war. However, before joining the Veinentines:

“... as though they thought it impious to begin war otherwise than with a crime, they stained their weapons with the blood of the new colonists, as they had previously with the blood of the Roman ambassadors ... ”, (4: 31: 8-9).

Fidenae now became the headquarters of the enemy army. Mamercinus duly marched on Fidenae with two of the consular tribunes in support:

✴Cossus (who was also master of horse) led the cavalry; and

✴T. Quinctius Poenus, who commanded a reserve army that was stationed in the hills above the city.

All three men played a significant role in the ensuing Roman victory:

“The slaughter in the city was not less than there had been in the battle, until, throwing down their arms, the [enemy survivors] surrendered to Mamercinus and begged that at least their lives might be spared. The city and camp were plundered. The following day the cavalry and centurions each received one prisoner... as this slave, those who had shown conspicuous gallantry, two; the rest were sold sub corona (by auction). Mamercinus led his victorious army, laden with spoil, back in triumph to Rome. After ordering Cossus to resign his office as master of horse, he resigned the dictatorship on the 16th day after his nomination, surrendering amidst peace the sovereign power that he had assumed at a time of war and danger (4: 34: 3-6).

Robert Ogilvie (referenced below, at pp. 584-5) observed that the year 426 BC had been:

“... decisive for the history of Rome's expansion north and east and of her mastery of the Tiber. After an unsuccessful attempt to exercise control over Fidenae by a colony ... , Roman strategy [had] turned to a blunt offensive against [the city], with the intention of destroying it for ever. Half-measures were not enough. Its dominating position sealed its fate. Only Romans could be trusted to guard the gateway to central Italy.”

Livy (‘History of Rome’, 4: 35: 2) recorded that, at the start of the following year, the Veientines were granted a truce of 20 years.

Aulus Cornelius Cossa and the Spolia Opima

As we have seen, Livy recorded that, when Cossus killed Lars Tolumnius, he became the first man since Romulus to win the outstanding honour of dedicating the armour of his victim, known as the spolia opima, in the temple of Jupiter Feretrius. A number of other surviving sources also record that Cossus won the spolia opima when he killed Lars Tolumnius. However:

✴while some agreed with Livy’s main account, in which Cossus won this honour as military tribune in 437 BC, while under the command of the dictator Mamercinus;

✴others asserted that he did so, either:

•as consul in 428 BC; or

•as military tribune with consular power and master of horse to Mamercinus (now dictator for the third time) in 426 BC.

Sources for 437 BC

At the start of the digression in Livy’s narrative (flagged above), he asserted that:

“I have followed all the existing authorities in stating that Cossus placed the spolia opima secunda [i.e., the first such spoils won since those won by Romulus] in the temple of Jupiter Feretrius when he was a military tribune”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 5).

In a surviving fragment of a now-lost part of the work of Dionysius of Halicarnassus, he recorded that Cossus killed Tolumnius and stripped him of his armour while serving as a military tribune:

“When the Etruscan Fidenates and Veientes were making war upon the Romans, and when Lars Tolumnius, ... was doing them terrible damage, a Roman military tribune, Aulus Cornelius Cossus ... knocked him from his horse and, while he was still attempting to raise himself, ran his sword through his groin. After slaying him and stripping off his spoils, he not only repulsed those who came to close quarters with him ... but also reduced to discouragement and fear those who still held out on the two wings [of the enemy army]”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 12: 5: 1-3).

Dionysius had previously recorded that Romulus had killed the king of Caenina and dedicated his armour as a trophy of war in the temple of Jupiter Feretrius (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 33: 1-4), although he did not describe this trophy as spolia opima. We cannot, therefore, be certain that he had originally recorded that Cossus had dedicated Tolumnius’ armour to Jupiter Feretrius.

Sources for 428 BC

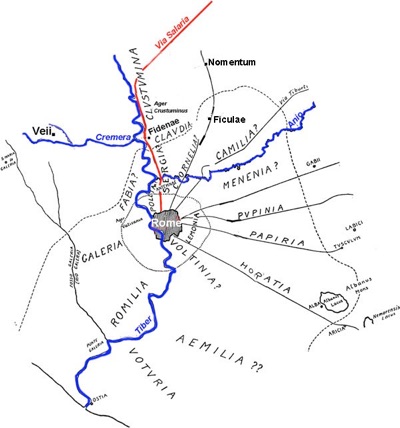

Opening lines of the fasti Triumphales (Musei Capitolini)

From ‘Mr Jennings’ on Flickr

Detail of ‘the inscribed fasti Triumphales, from the webpage by Digital Resource Commons, Ohio

Having justified his assumption that Cossus had killed Lars Tolumnius as military tribune in 437 BC, Livy acknowledged that:

“[there are two potential problems with this]:

✴[spoils of war] can only be designated as spolia opima if dux duci detraxit (they have been stripped from a commander by a commander), and we [Romans] know of no commander other than the one under whose auspices the war is conducted; and

✴I and my authorities are ... [also] confuted by the very words inscribed upon the spoils, which show that it was as consul that Cossus captured them”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 6).

Livy gave no source for the first of these objections (and it is not particularly important for the analysis that follows). However, his source for the second objection was impossible to ignore:

“Having heard from the lips of Augustus, ... [who] had himself read [the reference to Cossus as consul] on thorace linteo (a linen corslet) as he entered the temple of Jupiter Feretrius, ... I have thought it would be almost sacrilege to rob Cossus of such a witness to his spoils as [Augustus], the restorer of that very temple”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 7).

As noted above, Cossus was long-remembered as the first man in recorded history to emulate Romulus in winning the spolia opima. The surviving sources agree that only one other man followed in his footsteps in this respect: thus Plutarch (1st century AD), the most useful source for the present analysis, recorded that:

“Only three Roman leaders have attained [the] honour [of dedicating spolia opima to Jupiter Feretrius]:

✴Romulus first, for slaying Acron the Caeninensian;

✴next, Cornelius Cossus, for killing Tolumnius the Etruscan; and

✴lastly, Claudius Marcellus, for overpowering Britomartus, king of the Gauls, (‘Life of Romulus’, 16: 7).

All of the surviving sources that record Marcellus killed the king of the Gauls in battle (including the fasti Triumphales - see below) also record that he did so as consul in 222 BC.

Plutarch concluded his account above with a ‘dig’ against the account of at his fellow-countryman, Dionysius of Halicarnassus (ca. 7 BC):

“Cossus and Marcellus did indeed use a four-horse chariot for their entrances into the city, carrying the trophies themselves, [as Dionysius says]. However, [he] is incorrect in saying that Romulus [also] used a chariot ...”, (‘Life of Romulus’, 16: 8).

John Rich (referenced below, 2014, at p. 201, note 19) observed that Plutarch:

“... supposed that, like Marcellus in 222 BC, [Cossus dedicated the spolia opima] in the course of a chariot triumph, but whether this view was followed by the compilers of the [so-called fasti Triumphales] is quite uncertain, [since the relevant entry is lost]. Although the list’s entry for Marcellus’ triumph in 222 BC gives ample space to [the dedication of] his spolia opima, there is no mention of Romulus’ spolia opima in its opening entry for his first triumph.”

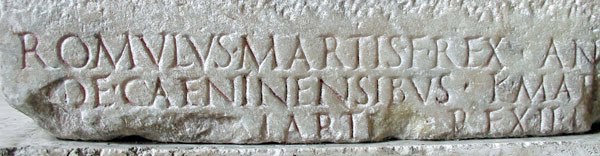

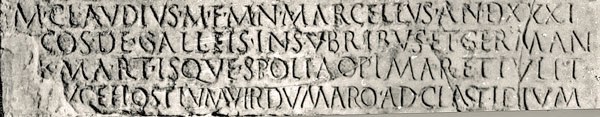

These two surviving entries in the fasti Triumphales (illustrated above) read:

✴ROMULUS MARTIS f. REX AN [I]

DE CAENENSIBUS K. MAR[T.]; and

✴M. CLAUDIUS M.f. M.n. MARCELLUS AN DXXXI

COS. DE GALLEIS INSUBRUS ET GERMAN

K, Mart. ISQUE SPOLIA OPIMA RETTULIT

DUCE HOSTIUM VVIRDOMARO AD CLASTIDIUM

John Rich reasonably assumed (at p. 246, Table 6, entry 41) that, given Augustus’ testimony, the Augustan fasti Triumphales recorded that Cossus triumphed de Veientibus as consul in 428 BC, although he left open the question of whether this entry also included his dedication of the spolia opima. Gavin Weaire (referenced below, at pp. 109-10) suggested that:

“Plutarch’s [assertion that Romulus did not use a chariot when dedicating the spolia opima] may, in fact, have been his own creation, inspired by artistic images of the tropaiophoric (trophy-bearing) Romulus.”

Weaire also noted (at p, 116) that the most famous image of this kind stood in the Forum Augustum from at least 2 BC. Similarly, Plutarch presumably based his assertion that both Cossus and Marcellus had dedicated the spolia opima during chariot triumphs on what he could read in the nearby fasti Triumphales: it seems to me that, given the testimony of Augustus himself, it is highly likely that that the record of Cossus’ triumph in 428 BC mirrored that for Marcellus in 222 BC.

Such an entry in the fasti Trumphales would not, of course, guarantee the authenticity of Augustus’ testimony: for example, scholars have frequently observed that this testimony is undermined by:

✴doubts about the likely authenticity of any inscription on a linen corslet that survived in the ruined temple in the late 1st century BC; and

✴the fact that Livy apparently had no way of verifying the information about it that he had heard attributed to Augustus.

However, Livy (probably wisely) confined himself to pointing out that there was no doubt that Cossus had held his consulship in 428 BC, and:

“... around [that] time, there were three years that were almost devoid of war because of plague and a shortage of corn, to the extent that some annals list nothing but the names of consuls, as if in mourning”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 9).

Sources for 426 BC

Livy suggested another possibility:

“The second year after Cossus’ consulship finds him:

✴as a military tribune with consular power; and

✴as master of the horse, in which capacity he fought a second famous cavalry battle”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 10).

What is more, according to Livy’s sources:

✴he had again fought under the overall command of Mamercus Aemilius Mamercinus (now dictator for the third time);

✴the battle was again fought at Fidenae against the Veientines and Fidenates; and

✴Mamercinus was again awarded a triumph.

However, on this occasion:

✴Fidenae had been definitively defeated; and

✴Cossus had consular power, and would thus have been able to claim Tolumnius’ armour as dux duci detraxit.

It is difficult to say whether Livy actually preferred this scenario to the one that he had apparently found in ‘all the existing authorities’.

There is, however, evidence that the sources that were available to Livy were more varied than he suggested. For example, Diodorus Siculus, whose work was broadly contemporary with that of Livy:

✴recorded nothing about events at Rome in 437 BC, the year that he covered at ‘Library of History’, 12: 80: 6-8; but

✴described events that Livy had placed in 438-7 BC in the year that Cossus was master of horse (i.e., 426 BC):

“... when ambassadors came to [Fidenae] from Rome, the Fidenates, put them to death for trifling reasons. Incensed at such an act, the Romans voted to go to war and ... appointed Anius (sic) Aemilius as dictator, with ... Aulus Cornelius as master of horse. Aemilius, ... marched with his army against the Fidenates ... heavy losses were incurred on both sides and the conflict was indecisive”, (‘Library of History’, 12: 80: 6-8).

The battle that Diodorus described here sounds like the holding operation that Livy had recorded in 437 BC, when the consul L. Sergius Fidenas held up the advance of the Veientine and Fidenate armies ahead of the appointment of the dictator Mamercinus.

A number of other sources insisted that spolia opima had to be won by a Roman under his own auspices; for example, Propertius (ca. 19 BC):

“Now, three [sets of spolia opima] are preserved in the temple, [which is] why it is called Feretrius:

✴because dux ‘ferit’ ense ducem (commander struck commander with a sword) ...; or

✴perhaps because [the three victorious Roman commanders] carried (ferebant) the captured arms on their shoulders ...”, (‘Elegies’ 4: 10: 49-52).

This, of course, throws no light on whether, in Propertius’ opinion, Cossus killed Tolumnius in 428 or 426 BC.

The Virgilian commentaries are similarly confusing: John Rich (referenced below, 1996, at p. 87 and note 3) observed that, in his commentary on ‘Aeneid’, 6: 841, which mentioned Cossus among a number of Roman heroes:

✴Servius recorded that Cossus won the spolia opima as ‘tribunus militum’; but

✴‘Servius Auctus’ added the words ‘consulari potestate’.

An anonymous work that probably dates to the 4th century AD has Cossus win the spolia opima as master of horse, but names the dictator as Quinctius Cincinnatus:

“The Fidenates, old enemies of the Romans, killed the legati who had been sent to them in order to fight with more courage, without hope of forgiveness; the dictator Quinctius Cincinnatus, sent against them, Cornelius Cossus as master of horse, who killed Lars Tolumnius with his own hand. He was the second after Romulus to dedicate spolia opima to Jupiter Feretrius”, (‘De Viris Illustribus Urbis Romae” 25, my translation)

However, one surviving source, Valerius Maximus (early 1st century AD), explicitly stated that Cossus won the spolia opima as master of horse [and hence as consular tribune]: in a section on examples of Roman bravery, he commented:

“I now come back to Romulus. Challenged to mortal combat by Acro, king of Caenina, and although ... it would have been safer to go into battle with his whole army than on his own, he preferred to seize the omen of victory with his own right hand. Nor did Fortune fail his undertaking. With Acro killed and the enemy put to flight, Romulus brought spolia opima from his foe to Jupiter Feretrius. So much for that; valour consecrated by public religion needs no private encomium:

✴Next to Romulus, Cornelius Cossus consecrated spoils to the same god when, as master of horse [in 426 BC], he met in battle and killed the leader of the Fidenates. Great was Romulus, for he began this kind of glory at its inception. Cossus too acquired much, in that he was capable of imitating Romulus.

✴Nor must we separate from these examples the memory of M. Marcellus. Such vigour of courage was in him that, by the Po [in 222 BC], he, with a few horsemen, attacked the king of the Gauls, who was surrounded by an enormous host, and straightway slew him, stripped him of his arms, and dedicated them to Jupiter Feretrius”, (‘Memorable Deeds and Sayings’, 3: 2: 3-5, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, at. p 239).

Analysis of Livy’s Chronology

Stephen Oakley (referenced below , 1997, at p. 24) observed that, for the period from ca. 450 BC:

“When literary embellishments have been swept away from [the work of Livy] and other [late annalists], we are left with a series of magistrates, treaties, triumphs, battles, laws and elections.”

He observed that oral tradition is unlikely to have played a major role in the transmission of this body of information, and pointed instead in the analysis that followed to pontifical and other ‘official’ records, family traditions, inscriptions, statues, monuments, and the work of antiquarians (often based on etymologies). Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at p. 243) argued that, in the context of the present discussion:

“Three monuments that survived in Rome into later historical times ... must have been the only solid data upon which the later historical tradition was based:

✴the statues [on the Rostra] of the four Roman [legati] whose deaths at the hands of the Fidenates sparked off the war;

✴the spolia opima won by Cossus from Lars Tolumnius, [which had been dedicated to Jupiter Feretrius at his temple on the Capitol]; and

✴a gold crown dedicated in the Capitoline temple by the dictator Mam. Aemilius to commemorate his victory over Fidenae.

In Livy’s narrative, the second and third items are linked together, and date to ... [437 BC], thus coming immediately after the murder of the [legates]. Yet, when the various tales associated with the Fidenate War are carefully examined, it appears likely that later Roman historians, eager to portray the Romans as having exacted swift revenge for the deaths of the [legates], transposed events from the close of the war to its very beginning.”

He also argued (at p. 425) that:

“Tolumnius’s death in [426 BC would make] excellent historical sense, for the king’s death would have abruptly ended Veientine support of Fidenae, and this in turn would have caused the immediate collapse of Fidenate resistance to Rome and the town’s capture or surrender.”

In that case, Cossus would have killed Tolumnius as consular tribune in 426 BC, and would have claimed Tolumnius’ armour as dux duci detraxit and thus as spolia opima. In the section below, I analyse Livy’s chronology with this argument in mind.

Murder of the Four Legates (438 BC)

In a speech that Cicero claimed to have delivered in the senate in 43 BC, he observed that:

“Lar Tolumnius, the king of Veii, murdered four legati of the Roman people at Fidenae, and their statues were still standing on the Rostra within my own recollection. The honour [payed to them by the erection of these statues] was well deserved: our ancestors gave those men who had encountered death in the cause of the Republic an imperishable memory in exchange for this transitory life” (‘Philippics’: 9:4).

This is the earliest surviving evidence for the tradition that Tolumnius was culpable in the murder of the legates at Fidenae, and provides the additional information that the original statues erected in their honour apparently survived in situ into the late Republic. More than a century later, Pliny the Elder (‘Natural History’, 34: 11) knew the names of the murdered legates who had been represented among the very old statues that had been erected on the Rostra. Thus, this long-remembered event was almost certainly historical, and there is no particular reason to doubt Livy’s testimony dating it to 438 BC.

Mamercinus’ Putative Triumph of 437 BC

Detail of ‘the inscribed fasti Triumphales, from the webpage by Digital Resource Commons, Ohio

John Lydus (‘De Magistratibus’, 1: 38), is the only surviving source apart from Livy for Mamercinus’ dictatorship and triumph of 437 BC. However, Mark Wilson,(referenced below, at p. 207, note 88), for example, warned that:

“... this is a late [ca. 550 AD] and sloppily unreliable source, especially in [the] section on dictators ... [at] 1: 36-8, in which names and actions of dictators were often garbled and conflated.”

He also suggested (at p. 524) that:

“Lydus’s reference [to first dictatorship of Mamercinus in 437 BC] might be conflated with the more well-known troubles of his third listed dictatorship, [in 426 BC].”

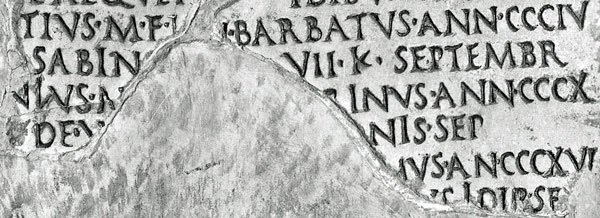

The entry for 437 BC in the fasti Capitolini is now lost. However, a fragment in the fasti Triumphales (made up of the two lines at lower right in the illustration above) records a triumph in this year:

“ .... [?]US AN CCCXVI (437/6 BC)/ .... US ID. SE[XT] ”

The fragment would have started with the name of a triumphant Roman commander:

✴In early editions of the inscription, the commander’s name was given as ‘...NUS’, and completed as [Mam. Aemilus Mamerci]nus.

✴However, it is now usually given as ‘...MUS’, in which case the cognomen should almost certainly be completed as Maximus. Interestingly, the ‘Chronography of 354 AD’ named the consuls of this year (317 AUC) as:

•Maximo; and

•Fidenato [L. Sergius Fidenas].

Some scholars suggest that there was an otherwis unrecorded suffect consul in this year with the cognomen Maxiumus, but John Rich (referenced below, 2014, at p. 199, note 10) argued against this, since suffects are otherwise unattested before 305 BC. Robert Ogilvie (referenced below, at p. 562) suggested instead that:

“... the Chronographer’s ‘Maximo’ is a simple corruption of ‘Macerino’;

and argued that:

“If ‘...MUS’ [rather than ‘...NUS’] is correct, then the restoration [Mam. Aemelius Mamercus Maxi]mus at least raises fewer objections [than an otherwise unrecorded suffect consul].”

John Rich (as above) supported Ogilvie’s conclusion:

“Earlier editors’ restoration of the dictator Mam. Aemilius Mamercinus, attested as triumphing in that year against the Veientines and Fidenates by [Livy and John Lydus], seems more plausible [than a mysterious suffect consul].”

In fact, none of these suggestions is convincing, particularly since the fragmentary inscription does not allow us to identify the defeated enemy. It is certainly reasonable to argue that:

✴the Augustan fasti recorded a triumph in this year; and

✴the reading of the commander’s name as ‘...MUS’ must be discarded because none of the surviving sources identifies a ‘...MUS’ with imperium in this year.

However, there were at least two candidates for a triumphant commander named ‘...NUS’:

✴the putative dictator Mam. Aemilius Mamercinus; and

✴the consul M. Geganius Macerinus (who was awarded a triumph in over the Volsci in 443 BC, as recorded in the fragmentary record ‘... RINUS ANN CCCX‘ immediately above the one under discussion here).

Furthermore, if Livy was correct in believing that the other consul, L. Sergius, adopted the cognomen ‘Fidenas‘ in recognition of his part in the war of this year, he might have been known previously as L. Sergius Esquilinus, assuming that he initially used the cognomen previously used by his ancestor, (L ?) Sergius Esquilinus, who served as decemvir in 450 and 449 BC. In short, Livy is our only surviving source of any importance for Mamercinus’ putative triumph of 437 BC.

Narrative of the War of 437-5 BC

If we modify Livy’s narrative for this war against Fidenae on the assumption that Cossus killed Lars Tolumnius in either 428 or 426 BC, then it would seem that Mamercinus achieved very little in 437 BC (even assuming that his dictatorship in this year is authentic): in Livy’s narrative:

✴In 437 BC

•L. Sergius, one of the serving consuls, checked the advance of the Veientines and Fidenates on Rome, albeit at great cost in Roman lives; and

•Mamercinus then pushed them back across the Anio and

“... hotly pursued the flying [enemy] legions and drove them to their camp with great slaughter, [although] most of the Fidenates, who were familiar with the country, escaped to the hills”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 19: 6).

✴In 436 BC, hostilities were suspended because of internal problems at Rome.

✴In 435 BC, the Veientines and Fidenates recrossed the Anio and advanced again on Rome. While the consuls defended the city, the dictator Q. Servilius:

“... followed them with an army eager for battle, and engaged them not far from Nomentum. The Etruscan legions were routed and driven into Fidenae”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 22: 2).

Servilius then gained access to the city (apparently by secretly tunnelling under its walls). Livy’s concluding sentence in this account is something of an anti-climax:

“ Whilst the attention of the [enemy] was being diverted from their real danger by feigned attacks, the shouts of the [Romans] above their heads showed them that the city was captured”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 22: 6).

✴In 434 BC, when the Veientines and the Faliscans requested aid against Rome from the national council of the Etruscans, Mamercinus was appointed to his second dictatorship. However, the other Etruscans refused to intervene and Mamercinus therefore resigned his office.

Thereafter:

“The pestilence [of 433 BC] kept everything quiet”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 25: 3).

Livy did not record a formal end to hostilities after the Romans’s capture of Fidenae in 435 BC, but it is clear from subsequent events that its ‘capture’ did not lead to its permanent submission to Rome. Furthermore, Livy subsequently recorded that, in 427 BC, when the Romans decided to declare war on Veii, it was first necessary to send fetial priests there to request reparations [as an alternative] because:

“There had been recent battles with the Veientines at Nomentum and Fidenae, and a truce had been made, not a lasting peace, but they had renewed hostilities shortly before its expiration”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 14-16).

In other words, the Romans felt obliged to seek reparations for alleged Veientine violations of the truce before declaring war on them. It is thus likely that Veientines had agreed a truce with Rome in or shortly after 435 BC, in return for the Romans’ withdrawal from Fidenae.

If we now look again at the facts that the cognomen Fidenas is only ever associated in the surviving sources with the Sergii and the Servilii and that the first member of these clans to use it were:

✴L. Sergius, the consul of 437 BC and

✴Q. Servilius, the dictator of 435 BC;

we might reasonably wonder whether there was a Roman tradition in which one or both of them (rather than Mamercinus) was/were responsible for the capture of Fidenae, albeit that subsequent problems at Rome prevented the Romans from securing the Fidenates’ definitive submission.

Q. Servilius Fidenas and the Capture of Fidenae (435 BC)

Even in Livy’s account, it was not Mamercinus but Servilius, as dictator in 435 BC, who actually captured Fidenae. However, his account of Servilius’ achievement is oddly matter-of-fact:

✴Before Servilius’ appointment:

“As the Faliscans could not be induced to renew the war, either by the representations of their [erstwhile Fidentate] allies or by the fact that Rome was prostrated by the epidemic, the Fidenates sent to invite [the aid of] the Veientine army, and the two states crossed the Anio and displayed their standards not far from the Colline gate”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 21: 8).

Louise Adams Holland (referenced below, at p. ) observed that Veientine:

“... attacks on Rome from the neighbourhood of the Porta Collina on the Quirinal clearly point to an approach from the direction of Fidenae.”

✴Immediately after his appointment, Servilius:

“... issued an order for all [Romans of military age] to muster outside the Colline gate by daybreak. Every man strong enough to bear arms was present. The standards were quickly brought to him from the treasury. While these arrangements were being made, the [Veientine and Fidenate armies] withdrew to the foot of the hills. [Servilius] followed them with an army eager for battle and engaged them not far from Nomentum. The [enemy] legions were routed and driven into Fidenae. [Servilius] surrounded the place with lines of circumvallation, ... [However], owing to its elevated position and strong fortifications, ... [but with little hope of] either storming the place or starving it into surrender ... [Instead, he ordered that a tunnel should be dug] ... At last, the tunnel was complete from [the Roman] camp to the citadel. Whilst the enemy’s attention was still diverted from the real danger by feigned attacks [from outside the walls], the shouts of the [Romans] above their heads showed them that the city was captured”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 22: 1-6).

Livy said nothing about:

•the fate of the men captured at Fidenae;

•any particular repercussions for those Fidenates who were deemed to have been responsible for the murder of the four Roman legates in 438 BC;

•any repercussions at all for Veii; or

•any arrangements for the administration of Fidenae under Roman control.

Perhaps even more surprisingly, he did not describe Servilius’ return to Rome at the head of the army that had avenged the murder of the four Roman legates three years before.

What is in a Name ?

This low-key description of Servilius’ achievements is surprising since, at least by 418 BC, the dictator of 435 BC was apparently known as Q. Servilius Fidenas. I say ‘apparently’ because the prosopography of the Servilii at this time was as confusing for Livy and his sources as it is for us. Thus, it is important to look at this potential evidence more carefully:

✴In his record of Servilius’ appointment as dictator in 435 BC, Livy named him as :

“... Quintus Servilius, whose cognomen some give as Priscus, others as Structus ...” , (‘History of Rome’, 4: 21: 10).

Elsewhere, whenever Livy used a cognomen for a Q. Servilius before 398 BC, it was always ‘Priscus’. For example, in his record of the appointment of a Q. Servilius as dictator in 418 BC, Livy recorded that:

“... what raised men’s courage most [was that] Quintus Servilius Priscus was ... named dictator”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 46: 11).

✴However, the entry in the fasti Capitolini for the dictator of 418 BC names him as:

‘Q. Servilius P.f. Sp.n. Priscus Fidenas II’.

We can fortunately link these two dictatorships together in Livy’s tangled account of the Servilii who served as magistrates in 418 BC:

✴One of the three consular tribunes of that year was, according to Livy:

“... C. Servilius, the son of the Priscus, in whose dictatorship Fidenae had been taken”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 45:5).

Livy thus identified the consular tribune C. Servilius as the son of Q. Servilius, the dictator of 435 BC.

✴After a military debacle in 418 BC caused by discord among the three consular tribunes:

“What did most to restore confidence was the nomination, by a senatorial decree, of Q. Servilius Priscus as dictator. ... He appointed as his master of the horse [either]:

•the tribune by whom he had been nominated, namely his own son, [according to] some authorities; [or]

•[as] others say, ... Ahala Servilius ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 46: 10-2).

Thus, Livy also identified the consular tribune C Servilius as the son of Q. Servilius, the dictator of of 418 BC.

In fact, Livy was almost certainly mistaken in his assertion that the consular tribune of 418 BC was the son of the dictator who then appointed his as his master of horse: the fasti Capitolini are surely correct in identifying:

✴the dictator of 418 BC as Q. Servilius P.f. Sp.n. Priscus Fidenas II;

✴one of his sons (presumably the eldest) as Q. Servilius Fidenas Q.f. P.n., the consular tribune of 402, 398, 395, 390, 388 and 386 BC; and

✴the consular tribune of 418 BC as C. Servilius Q.f. C.n. Ahala (the son of another Quintus, whose grandfather was called Caius, not Publius.

However, what is important here is that Livy acknowledged that the dictators of 435 and 418 BC were one and the same man: Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 428 and p. 453) arrived at the same conclusion by analysing the nomenclature of the consular tribune of 402-386 BC.

In short, Q. Servilius Priscus, the dictator of 435 BC, almost certainly acquired the cognomen Fidenas in recognition of his capture of Fidenae in that year, and his son continued to use it throughout his illustrious career. This surely indicates a tradition in which Servilius’ capture of Fidenae in 435 BC was represented as a major event in Roman history.

Servilius’ Second Dictatorship (418 BC)

This digression into Livy’s account of Servilius’ second dictatorship provides some additional information for the discussion here. According to Livy, when war broke out with the Aequi and the Latins of Labici (between Praeneste and Tusculum) in 418 BC, it was agreed that two of the three consular tribunes, L. Sergius Fidenas and M. Papirius Mugilanus, would be given military command and, since they would not co-operate with each other, that they would hold command on alternate days. Soon after, Sergius led the army into an ambush contrived by the Aequi. His army fled in disarray into their camp but:

“... after the enemy had surrounded a considerable part of it, [the Romans] evacuated it in a disgraceful flight through the rear gate. The commanders and military legates, together with as much of the army as remained with the standards, made for [nearby] Tusculum, while the others ... fled to Rome and spread the news of a more serious defeat than the one that had actually occurred. ... [The third consular tribune, C. Servilius, calmed the panic in Rome and nominated] Q. Servilius Priscus as dictator, and he appointed the tribune who had nominated him [i.e., C. Servilius], as his master of horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 46: 6-10).

Immediately after his appointment, Q. Servilius set out from Rome with a fresh army and, having established his camp near that of the Aequi, ordered the Roman troops still at Tusculum to report for duty. Thereafter:

“After shaking the enemies' forward ranks with a cavalry charge, [Servilius] ordered the standards of the legions to be rapidly advanced and, as one of his standard-bearers hesitated, he killed him. [After this], so eager were the Romans to engage that the Aequi crumpled. Driven from the field, ... the Aequi made for their camp,... [which was swiftly taken. Intelligence arrived that] the defeated Labicans and a large proportion of the Aequi had fled to Labici. On the following morning, the army marched to Labici ..., [which] was captured and plundered. After leading his victorious army home, [Servilius] laid down his office just eight days after he had been appointed. ... the Senate ... decreed that a body of colonists should be settled at Labici. 1,500 colonists were sent from Rome, and each received 2 iugera of land”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 47: 2-6).

Livy’s account is broadly supported by:

✴the record in the Augustan fasti Capitolini that:

•the consular tribunes of this year were

-[M. Papirius L.f. . .] Mugillanus

-C. Servilius Q.f. C.n. Ahala II

-L. Sergius C.f. C.n. Fidenas III; and

•there was also a dictator, Q. Servilius P.f. Sp.n. Priscus Fidenas II, who appointed [C. Servilius] Q.f. C.n. Ahala as his master of horse; and

✴Diodorus Siculus, who record that, in this year:

“... the Romans went to war with the Aequi and reduced Labici by siege”, (‘Library of History’, 13: 6: 8).

The account is further supported by the fact that Livy’s account of the colonisation of Labici in this year is likely to be based on authentic records: as Monica Chiabà (referenced below, at pp. 93-4) observed, this is the first time in the context of federal colonisation in the 5th century BC that Livy recorded the precise number of colonists sent out and the precise amount of land that was allotted to each of them. Indeed, Robert Ogilvie (referenced below, at p. 605) argued that, apart from an obscure detail relating to the way in which the army of the consular tribunes had been levied:

“... the capture of Labici and its colonisation are the only genuine events of the whole year.”

This might be slightly over-stated, since a successful Roman response to raids around Tusculum by the Aequi and the Labici might well have been a precursor to the foundation of this colony. Furthermore, as Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 43) observed, since the people of Tusculum were assigned to the Papiria tribe after their incorporation into the Roman state in 381 BC, it is possible that this tribal territory had already been extended outwards from Rome to encompass land confiscated at nearby Labici in 418 BC. Nevertheless, Ogilvie was right to remind us that Livy is our only surviving source for Rome’s putative war with the Aequi and the Labici in 418 BC.

That leaves open the question of whether Livy’s account of Servilius’ military exploits in his second dictatorship, supported in the surviving sources only by the by entry in the fasti Capitolini, is of any value. For example, Mark Wilson (referenced below at pp. 273-5) observed that this was one of only two occasions in the surviving record of the Republican dictatorship in which a dictator was needed because the serving consular tribunes failed in their exercise of military commands: the other occasion had arisen in 426 BC, when (as we have seen) an army led by three of the four consular tribunes had suffered a disgraceful defeat at the hands of the Veientines, following which:

“The [Roman] people, unused to being defeated, were despondent; despising the tribunes, they begged for a dictator, in whom rested the hope of the state. ... [The fourth consular tribune], Aulus Cornelius [Cossus], named as dictator Mamercus Aemilius [Mamercinus] and was himself appointed by Mamercus master of the horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 31: 4).

For completeness, Wilson also noted (at p. 399, note 70) a third occasion on which a consular tribune nominated a dictator who then appointed his nominator as his master of horse: according to Livy, in 408 BC, when two of the three consular tribunes would not agree to the appointment of a dictator in the face of a threat from Antium (or possibly Antinum), supported by the Volsci and the Aequi, the third of them, C. Servilius Ahala, unilaterally nominated P. Cornelius Rutilus Cossus, who returned the compliment by appointing him as master of horse. On this occasion:

“The war was far from being a memorable one. The enemy were defeated with great slaughter at Antium in a single easily-won battle. The victorious army devastated the Volscian territory. The fort at Lake Fucinus was stormed, and the garrison of 3,000 men taken prisoners, whilst the rest of the Volscians were driven into their walled towns, leaving their fields at the mercy of the enemy. ... the dictator [Cossus] returned home with more success than glory and laid down his office”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 57: 6-8).

These three dictatorships have a number of common characteristics:

✴each was needed because of the failure of the serving consular tribunes to deal with a military threat:

✴in each case, a ‘good’ consular tribune who was untainted by the events leading up to the failure nominated a dictator who then appointed him as master of horse; and

✴the dictator dealt quickly and successfully with the military threat:

•in 418 and 408 BC, the actual threat was minor; and

•although the threat in 426 BC was more substantial, the dictator was able to deal with it in only 16 days.

We can be reasonably certain that Mamercinus was appointed as dictator in 426 BC specifically in order to deal with the Veientine threat. Furthermore, it is at least possible that his intervention was needed because of failures on the part of three of the four consular tribunes. However, even if the dictatorships of 418 and 408 BC were authentic, it seems that Livy had very little secure information: he or his sources might simply have assumed that these two dictators were needed for military reasons and elaborated the respective narratives by drawing, in part, on the events of 426 BC.

With this possibility in mind, we might look again at Ogilvie’s suggestion (above) that Livy’s account of Servilius’ achievements as dictator in 418 BC had been largely invented to explain the foundation of the colony at Labici in that year. One has to agree that the narrative is very thin:

“After shaking the enemies' forward ranks with a cavalry charge, [Servilius] ordered the standards of the legions to be rapidly advanced and, as one of his standard-bearers hesitated, he killed him. [After this], so eager were the Romans to engage that the Aequi crumpled”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 47: 2-6).

This execution was the key to what followed: Servilius’ army became so eager to obey that, within eight days, the Aequi and their allies were routed, and Labici was captured and removed from the sphere of influence of the Aequi, to the extent that its territory could be assigned to viritane settlers from Rome. Furthermore, it is possible that the anecdote of the execution of the hesitant standard-bearer did not really belong to a tradition relating to a war with the Aequi: in a list of examples of the strategies that had been used to restore the morale of Roman armies in the Republic, the military strategist Frontinus (1st century AD) recorded that:

“The dictator Servilius Priscus, having given the command to carry the standards of the legions against the hostile Faliscans, ordered the standard-bearer to be executed for hesitating to obey. The rest [of the army], cowed by this example, advanced against the foe”, (‘Stratagems’, 2: 8:8).

To adjudicate between these two conflicting traditions, we must look again at Livy’s account of Servilius’ dictatorship of 435 BC. Military standards certainly featured in it:

✴the Fidenates and Veientines planted theirs not far from the Colline gate; and

✴the Roman quickly brought theirs from the treasury as Servilius mustered his army in front of the gate.

However, Livy did not record that any of the Roman standard-bearers were hesitant to follow his order to advance: all he said here was that, as the enemy withdrew:

“[Servilius] followed [the withdrawing enemy army] with [his own] army eager for battle”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 22: 2).

Furthermore, although he recorded that the Faliscans had fought in the war in 437 BC, and that the Romans had raided their territory in the following year, he explicitly stated that they had declined to take part in the advance on Rome in 435 BC. It seems to me that:

✴Livy and Frontinus almost certainly relied on a single tradition in which Servilius executed a standard-bearer who hesitated to advance on a hostile Faliscan army; but

✴Livy:

•decided against incorporating this anecdote into his account of Servilius’ first dictatorship because he had other sources that insisted that the Faliscans had not participated in the hostilities of that year; and

•used it instead to pad out his apparently scant information on the events of Servilius’ second dictatorship.

Q. Servilius Fidenas and the Capture of Fidenae (435 BC): Conclusions

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 453) pointed out, Livy frequently pointed to Servilius’ renown as a statesman: for example, in his record of the events that led up to his appointment as dictator for the second time in 418 BC, Livy stressed the respect with which his opinions were apparently received. Having said that, Livy seems to have been quite selective in his use of the traditions that related to Servilius’ first dictatorship, in which he defeated Veientine and Fidenate armies and captured Fidenae: for example, he seems to have:

✴privileged sources that excluded the Faliscans from these hostilities; and

✴consequently omitted the anecdote relating to Servilius’ execution of the hesitant standard-bearer from his account of this year, instead adapting it for use in his otherwise thin account of Servilius’ achievements as dictator in 418 BC.

It seems that Livy regarded Servilius’ capture of Fidenae comes as something of an anti-climax following:

✴Cossus’ putative killing of King Tolumnius of Veii in 437 BC; and

✴Mamercinus’ putative triumph over the Veientines and Fidenates after this battle, which was accompanied by Cossus’ putative dedication of Tolumnius’ armour as spolia opima.

If, however, Cossus killed Tolumnius while serving as Mamercinus’ master of horse in 426 BC (as, for example, Garry Forsythe suggested), then Servilius’ capture of Fidenae in 435 BC would have been an important event in Roman history, coming as it did only four years after the murder of four Roman legates at Fidenae. I think that this was arguably the case, as reflected in the facts that

✴Servilius himself was subsequently given the cognomen Fidenas; and

✴his son continued to use this cognomen throughout his illustrious career.

Consulship of Aulus Cornelius Cossus (428 BC)

According to Livy:

“The Veientines launched raids into Roman territory [in this year], and it was rumoured that some of the Fidenates had taken part in them”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 5-7).

The Romans sent three commissioners to Fidenae, apparently in order to investigate the participation of some Fidenates. However, as discussed above, Robert Ogilvie (referenced below, at p. 583) reasonably suggested that:

“... the iiiviri, [L. Sergius Fidenas, Q. Servilius Fidenas and Mam. Aemilius Mamercinus might have been] ... iiiviri coloniae deducendae, [particularly since] they included one consular in L. Sergius. It would be a typical misinterpretation of the Annales.”

In other words, it is likely that the Romans attempted to found a colony at Fidenae in this year, perhaps on land that they already controlled but more probably on land that they had seized from the Fidenates in 435 BC: if so, this would explains why the truce that was apparently still in force between Rome and Veii came under strain. Nevertheless, in Livy’s account, Rome itself suffered from a serious drought and:

“Hostilities with the Veientines were postponed till the following year ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 12).

However, as discussed above, the Augustan fasti Trumphales (ca. 19 BC) almost certainly reflected Augustus. testimony that Cossus killed Tolumnius in battle in this year and duly celebrated a triumph: thus, John Rich (at p. 246, Table 6, entry 41) suggested two entries that would have been included in a now-lost part of the inscription, recording that:

✴Cossus triumphed de Veientibus as consul in 428 BC; and

✴Mamercinus triumphed de Veientibus as dictator in 426 BC.

However, in addition to his assertion above, Livy had earlier recorded that, around the time of Cossus’ consulship:

“... there were three years that were almost devoid of war because of plague and a shortage of corn, to the extent that some annals list nothing but the names of consuls, as if in mourning”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 9).

It seems to me that Livy’s observation has to be decisive: while the Roman annalists almost certainly recorded some fabricated Roman victories over Veii in the 5th century BC, they surely would not have been ignorant of an actual battle in which a serving consul killed King Lars Tolumnius of Veii with his own hands.

Fall of Fidenae (427-6 BC)

Events of 427 BC

Livy recorded that, at the start of the next consular year:

“... the formal declaration of war [on Veii] and the despatch of troops were delayed on religious grounds; it was considered necessary that the fetials should first be sent to demand satisfaction. [This problem arose because] there had been recent battles with the Veientines at Nomentum and Fidenae, and a truce had been made, not a lasting peace, but before the days of truce had expired, [the Veientines] had renewed hostilities. Nevertheless, fetials were sent, but, when they presented their demands in accordance with ancient usage, they were refused a hearing”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 13-15).

Thus, it seems that Veientines had agreed a truce with Rome in or shortly after 435 BC, presumably in return for the Romans’ withdrawal from Fidenae. Livy seems to claim here that the Veientines had now given cause for a just war because they had:

✴broken the truce by raiding Roman territory in 428 BC; and

✴ignored the fetials’ demands for restitution.

However, this could well be special pleading, since the Romans might well have violated the truce by preparing to found (or re-found) a colony at Fidenae in 428 BC.

Livy suggested that the rest of this consular year was taken up with internal politics:

“A question then arose as to whether war should be declared by:

✴the mandate of the people; or

✴[simply] a resolution passed by the Senate

The tribunes [of the plebs] threatened to stop the levying of troops and succeeded in forcing the consul Quinctius [sic] to refer the question to the people. The [plebeian] centuries decided unanimously for war. The plebs gained a further advantage in preventing the election of consuls for the next year”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 15-16).

IN CONSTRUCTION FROM THIS POINT

Events of 426 BC

Livy

(‘History of Rome’, 4: 31-34) recorded that, because of pressure from the plebs, four consular tribunes were elected for 426 BC: war was duly declared, following which:

✴three of the consular tribunes marched against Veii; while

✴the fourth, Aulus Cornelius Cossus, was designated as urban prefect, charged with administering and defending Rome.

The conduct of the war was disastrous, and the people:

“... demanded a dictator ... Here too, a religious impediment arose, since only a consul could nominate a dictator. The augurs were consulted and removed the difficulty: [Cossus] nominated Mamercus Aemilius as dictator [for the third time] and he appointed Cossus as his master of horse”, (4: 31: 4-5).

Mamercinus restored morale by reminding the Romans that he was:

“... the same Mamercus Aemilius who had defeated the combined forces of Veii and Fidenae, supported by the Faliscans, at Nomentum: his master of the horse ... [was] the same Aulus Cornelius who, as military tribune, had killed Lars Tolumnius, king of Veii, in full sight of both armies, and had carried the spolia opima to the temple of Jupiter Feretrius”, (4: 32: 4-5).

Meanwhile, the Fidenates had decided to take part in the war. However, before joining the Veinentines:

“... as though they thought it impious to begin war otherwise than with a crime, they stained their weapons with the blood of the new colonists, as they had previously with the blood of the Roman ambassadors ... ”, (4: 31: 8-9).

Fidenae now became the headquarters of the enemy army. Mamercinus duly marched on Fidenae with two of the consular tribunes in support:

✴Cossus (who was also master of horse) led the cavalry; and

✴T. Quinctius Poenus, who commanded a reserve army that was stationed in the hills above the city.

All three men played a significant role in the ensuing Roman victory:

“The slaughter in the city was not less than there had been in the battle, until, throwing down their arms, the [enemy survivors] surrendered to Mamercinus and begged that at least their lives might be spared. The city and camp were plundered. The following day the cavalry and centurions each received one prisoner... as this slave, those who had shown conspicuous gallantry, two; the rest were sold sub corona (by auction). Mamercinus led his victorious army, laden with spoil, back in triumph to Rome. After ordering Cossus to resign his office as master of horse, he resigned the dictatorship on the 16th day after his nomination, surrendering amidst peace the sovereign power that he had assumed at a time of war and danger (4: 34: 3-6).

Robert Ogilvie (referenced below, at pp. 584-5) observed that the year 426 BC had been:

“... decisive for the history of Rome's expansion north and east and of her mastery of the Tiber. After an unsuccessful attempt to exercise control over Fidenae by a colony ... , Roman strategy [had] turned to a blunt offensive against [the city], with the intention of destroying it for ever. Half-measures were not enough. Its dominating position sealed its fate. Only Romans could be trusted to guard the gateway to central Italy.”

Livy (‘History of Rome’, 4: 35: 2) recorded that, at the start of the following year, the Veientines were granted a truce of 20 years.

Frontinus

In Livy’s narrative, the only substantial engagement in this war took place in 356 BC:

“The ... consul [Marcus Fabius Ambustus], who was operating against the Faliscans and Tarquinians, met with a defeat in the first battle. The main reason was the extraordinary spectacle presented by the Etruscan priests, who brandished lighted torches and had what looked like snakes entwined in their hair like so many Furies. This produced a real terror amongst the Romans, ... who rushed in a panic-stricken mass into their entrenchments. The consul and his staff ... mocked and scolded them for being terrified by conjuring tricks like a lot of boys. Stung by a feeling of shame, they ... rushed like blind men against [the priests] from whom had just fled. After scattering the [priests], they engaged with the armed men behind them and routed the entire army. The same day, they gained possession of the enemy camp and, after securing an immense amount of booty, returned home flushed with victory, ... deriding [both] the enemy's contrivance and their own [initial] panic”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 17: 2-6).

“The Faliscans and Tarquinians disguised a number of men as priests, and had them hold torches and snakes in front of them, like Furies. Thus they threw the army of the Romans into panic. On one occasion the men of Veii and Fidenae snatched up torches and did the same thing”, (‘Stratagems’, 2: 4: 18-9) 356/ 426 BC

Cornelius Cossus, master of the horse, did the same in an engagement with the people of Fidenae. Tarquinius, when his cavalry showed hesitation in the battle against the Sabines, ordered them to fling away their bridles, put spurs to their horses, and break through the enemy's line”, (‘Stratagems’, 2: 8: 8-10)

431 BC: (‘History of Rome’, 4: 26-29)

The only major war in the period was fought against the Aequi and the Volsci, who had both raised armies under leges sacratae. I include it here because one aspect of Livy’s account may be relevant to the present discussion: