Romans

Roman Temples: Temple of Jupiter Feretrius

Linked pages: Collegium Fetialum; Spolia Opima; Temple of Jupiter Feretrius

Romans

Roman Temples: Temple of Jupiter Feretrius

Linked pages: Collegium Fetialum; Spolia Opima; Temple of Jupiter Feretrius

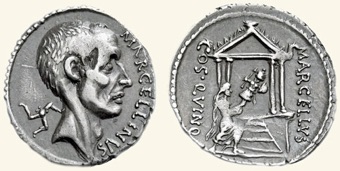

Denarius (RRC 439/1) issued in Rome, probably issued by [P] Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus in ca. 50 BC

Obverse: MARCELLINVS; head of M. Claudius Marcellus (with triskele behind, for his capture of Syracuse)

Reverse: MARCELLVS COS·QVINQ (for his five consulships):

Marcellus carries the spolia opima (which he won in 222 BC) into the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius (see below)

The early history of the temple of Jupiter Feretrius is known to us primarily through:

✴the tradition that it stood on the site of a shrine that Romulus had built on the Capitol for the dedication to Jupiter Feretrius of the arms of the king of Caenina, whom he had killed in battle with his own hands; and

✴the fact that two later Roman commanders:

•Aulus Cornelius Cossus , in 437, 428 or 426 BC; and

•Marcus Claudius Marcellus, in 222 BC;

each of whom had also killed an enemy commander in battle with his own hands, had been given the honour of stripping the armour from his vanquished foe and dedicating it to Jupiter Feretrius as the spolia opima.

Early Sources for the Temple

Cnaeus Naevius (ca. 270 - 200 BC)

Eric Warmington (referenced below, 1936, at pp. xiv-xvii) summarised the career of the Campanian poet and dramatist Naevius. He arrived in Rome after serving in the First Punic War and began to produce plays there in about 235 BC. He seems to have made powerful enemies, and was exiled to Utica in northern Africa in ca. 202 BC, shortly before his death. None of Naevius’ works survive, although fragments of some of them are found in our surviving sources.

Naevius is usually credited for having introduced a theatrical genre known as the fabula praetexta to Rome. Harriet Flower (referenced below, 1995, at p. 171) observed that theatrical productions of this kind:

“... presented a Roman aristocrat wearing the garb denoting his office and rank [i.e., the toga praetexta] and fulfilling his official duties for the good of the state”.

She commented that:

“Praetextae were written either:

✴about events of early Roman history, such as Naevius' ‘Romulus’ ... ; or

✴about recent exploits [of prominent Romans], such as Naevius' ‘Clastidium’ ...

These are the only two known works by Naevius in this genre, and (as we shall see) only small fragments of each survive. Both works are potentially relevant to the present discussion.

‘Romulus’

We know of the existence of the ‘Romulus’ from only two fragmentary references to it:

✴Varro referred to it in a passage about the vocabulary used in connection with the carding of wool: specifically, he referred to things that are removed in the cleansing of wool, which:

“... in the ‘Romulus’, Naevius calls ‘asta’, from the Oscan”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 7: 54, translated by Roland Kent, referenced below, at p. 319).

✴Donatus, in his commentary on Terentius’ ‘Adelphi’, asserted that:

“The story that, when a fabula of Naevius was being performed in the theatre, a she-wolf broke in at the scene of the feeding of Remus and Romulus, is false”, (‘ad Ter.: Adelph.’, 6: 1: 21 , translated by Eric Warmington, referenced below, 1936, at p. 137).

It is obviously possible that this play included a dramatisation the traditions relating to Romulus’ victory over the king of Caenina and his foundation of a shrine to Jupiter Feretrius, to whom he dedicated the arms that he stripped from the king’s body after having killed him with his own hands.

‘Clastidium’

Harriet Flower (referenced below, 2000, at p. 36) observed that Naevius’ ‘Clastidium’:

“... is the first recorded [Roman] history play to deal with a closely contemporary subject.”

As Gary Forsythe (referenced below, 1994, at p. 181) observed, it would have been:

“... a contemporary dramatisation of Marcellus’ great exploit [in winning the spolia opima at the Battle of Clastidium in 222 BC].”

We know of this play from only two fragments of it, both in passages by Varro:

✴“... there are many words still remaining in the poets, whose origins could be set forth; as in Naevius, ... ‘in the Clastidium’: ‘vitulantes’ (singing songs of victory), [is derived] from Vitula (goddess of Joy and Victory)”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 7:107, translated by Roland Kent, referenced below, at pp. 361-3); and

✴“... the following [is from] Naevius’ Clastidium: ‘Back to his native land, happy in life, never dying’”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 9: 78, translated by Roland Kent, referenced below, at p. 501).

Sander Goldberg (referenced below, at p. 32) observed that the second of these fragments:

“... suggests a victorious general who has safely returned home, as does the one other attested word [in the first fragment], vitulantes (celebrating).”

Gary Forsythe (referenced below, 1994, at p. 181) agreed, adding that:

“... it seems highly probable that [the play] also contained (by way of background) the earliest account of Romulus’ winning the first spolia opima and [his foundation and dedication] of the first [shrine] of Jupiter Feretrius.”

Dating of the ‘Romulus’ and the ‘Clastidium‘

The ‘Romulus’ and the ‘Clastidium’ were almost certainly first performed while Naevius was still in Rome:

✴Since both Romulus (traditionally) and Marcellus had dedicated spolia opima to Jupiter Feretrius, it is sometimes assumed that the two plays were performed in relatively quick succession: for example, Eric Warmington (referenced below, 1936, at p. xv) suggested that the ‘Clastidium’ was staged in 222 BC and that the ‘Romulus’ was perhaps staged soon after. However, there is, in fact, nothing to preclude a gap of some years between the two performances.

✴The ‘Clastidium’ obviously post-dated 222 BC. It is sometimes assumed that it could not have been performed in Marcellus’ lifetime, and that it was therefore probably performed either:

•at his funerary games in 208 BC; or

•in 205 BC, when the temple of Honor and Virtus, which he had vowed at Clastidium, was finally dedicated by his son (as suggested, for example, by Harriet Flower,referenced below, 2000, at p. 36).

However, Sander Goldberg (referenced below, at pp. 32-3 and note 12) pointed out that there is no hard evidence that would rule out a performance while Marcellus was still alive.

Furthermore, as Harriet Flower (referenced below, 2000, at p. 36) pointed out, we do not actually]know which play was performed first:

✴As we have seen, Eric Warmington suggested that the ‘Romulus’ followed shortly after the ‘Calstidium’/

✴Harreit Flower (as above) suggested that:

“... we may suspect that [the ‘Romulus’ came first], which, in turn, suggested Marcellus as a similar subject.”

All we can really say is that:

✴the ‘Romulus’ could have had its first performance at any point in ca. 235-202 BC; and

✴the ‘Clastidium’ at any point in 222-202 BC.

Even if the temple of Jupiter Feretrius had not featured in the ‘Romulus’, it would certainly have featured in the ‘Clastidium’, as the temple in which Marcellus dedicated the spolia opima in 222 BC.

Quintus Ennius (239 - 168 BC)

The Calabrian Ennius, who arrived in Rome in 204 BC, was the author of the ‘Annales’, the great epic poem that he wrote at an unknown date before his death in 168 BC. Eric Warmington (referenced below, 1935, at p. xxv) observed that, in this work, he:

“... told the story of Rome from the arrival of Aeneas down to events of his own time, ... [in a work that was] quintessentially Roman in its display of Roman achievements portrayed with Homeric grandeur ... Ennius gave Roman epic its canonical shape and pioneered many of its most characteristic features. His ‘Annals’ quickly became a classic.”

Warmington also pointed out (at p. xxvii) that:

“While no work of Ennius survives complete, more survives in fragments than of any of the other ‘lost’ poets of early Rome, a clear indication of his importance to later readers.”

One of these surviving fragments, which was cited by a now-unknown grammarian in his commentary on Virgil’s ‘Georgics’ (2: 384), records that:

“When Romulus had built a templum Iovi Feretrio, he caused greased hides to be spread out and held games [in which] men fought with gauntlets [presumably resembling boxing gloves] and competed in running races; Ennius bears witness to this fact in the ‘Annales’”, (translated by Eric Warmington, referenced below, 1935, at p. 35).

Jackie Elliott (referenced below, at p. 256) recorded three separate manuscripts in which this wording, or something very like it, survives.

Gary Forsythe (referenced below, 1994, at p. 181) suggested that Ennius’ source for this passage was likely to have been Naevius‘ ‘Clastidium’ (above). According to Eric Warmington (referenced below, 1935, at pp. xxii):

“We do not know that [Ennius] was ever acquainted personally with ... Naevius, ... [whose] exile came at about the time that Ennius reached Rome.”

However, he would surely have been aware of Naevius’ works, including those discussed above. Be that as it may, this surviving fragment from Ennius’ ‘Annales’ is the earliest secure source for the tradition that Romulus’ founded of a templum (perhaps an open-air shrine) to Jupiter Feretrius.

Lucius Calpurnius Piso Frugi (ca. 180 - 110 BC)

Piso was a prominent statesman who became consul in 133 BC and censor in 120 BC. His history of Rome, which covered the entire period from the mythical foundation to Piso’s own time, was probably written after his censorship and entitle the ‘Annales’. Again, this work is lost, but it is known from a number of fragments in the works of other authors. One of these authors, Tertulian, recorded in a work that he published in ca. 200 AD that:

“... Romulus instituted games in honour of Jupiter Feretrius at the Tarpeian Rock, which, according to the tradition handed down by Piso, were called [both] the Tarpeian and the Capitoline Games.”, (‘De Spectaculis’, 5, search on ‘Feretrius’).

Tertulian cited Suetonius (died after 122 AD), who presumably included this information, citing Piso, in his now-lost ‘On Roman Spectacles and Games’.

Ludi Tarpeii/ Capitolini Dedicated to Jupter Feretrius ?

The passages by Ennius and Piso, taken together, indicate a tradition that was established by at least the 2nd century BC, according to which, games in honour of Jupiter Feretrius were:

✴established by Romulus after he built the temple to Jupiter Feretrius (Ennius); and

✴dedicated to Jupiter Feretrius and held at the Tarpeian Rock (Piso)

Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at pp. 178-9) suggested that these games were thought to have been held at the time of Romulus’ victory at Veii, which was his final victory before his death.

As we have seen, Varro subsequently recorded the tradition that the name of the hill on which these games would have been held had changed from ‘Tarpeian’ to ‘Capitoline’ in the late regal period.

Despite the fragment from Piso quoted by Tertulian, it is unlikely that Piso recorded that these games were known as both the Ludi Tarpeii and Ludi Capitolini at the same time. Dionysius of Halicarnassus regarded him as an authority on the legend of Tarpeia, and cited him five times in the three paragraphs that he devoted to her legend. In the last of these, he recorded that tarpeia:

“... was honoured with a monument in the place where she fell and lies buried on the most sacred hill of the city, and the Romans perform libations to her every year: I record here what Piso writes. If she had died in betraying her country to the enemy, [as other authorities claimed], she would [surely] not have received any of these honours ... [Rather], if there had been any remains of her body, they would... have been cast out of the city, in order to warn and deter others from committing similar crimes”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 40: 3).

Dionysius did not say that Tarpeia was given the honour of having the ‘Tarpeian Hill’ named after her, but Piso would surely have included that claim as he justified his alternative version of her legend. Furthermore, he would surely have been aware of the tradition that the hill was subsequently renamed, and he may well have been one of Varro’s sources for his account of the renaming of the hill. However, he was probably not Varro’s only source: Edward Bispham and Timothy Cornell (in their commentary on a fragment by Fabius Pictor in T. J. Cornell, referenced below, Volume III, at pp. 45-6), pointed out that the scene of the discovery of the head under the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus had been depicted on gems as early as the 3rd century BC. Thus, although the late fragment that they were addressing in their commentary named only ‘Fabius’ among the cited sources, they concluded (at p. 47) that this might well have been Fabius Pictor, who was writing in ca. 200 BC), albeit that:

“... he may have done no more than tell the story of the head and derive the name of the Capitol from it.”

Given this background, Piso would surely have known that any tradition that Romulus had established games dedicated to Jupiter Feretrius should have identified them as Ludi Tarpeii, and that the name Ludi Capitolini was either

✴an anachronistic reference to the games that Romulus held at the Tarpeian Rock according to roman tradition; or

✴an accurate reference to games held on the Capitol at a much later date.

Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at p. 180) suggested that an earlier writer:

“... could have assigned the origin of these games to Romulus ... [but] termed them ‘Capitoline’, [in which case] Piso merely corrected an anachronistic ‘Capitoline’ to ‘Tarpeian’.”

In other words, while it is possible that Roman tradition held that Romulus held games dedicated to Jupiter Feretrius, nothing in the surviving sources indicates that such games were actually held during the regal period or thereafter.

It is true that the games known as the Ludi Capitolini were held in the Republic: Livy recorded a tradition that, after the Gallic sack of Rome, the Senate decreed that:

“Ludi Capitolini were to be instituted, because Jupiter Optimus Maximus had protected his dwelling-place [i.e., his temple on the Capital] and the arx (citadel) of Rome in the time of danger, and the dictator [Camillus] was to form a college [of priests] from amongst those who were living on the Capitol and in the citadel”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 50: 4).

He returned to this event in the speech he gave to Camillus, arguing against the suggestion that the Romans should abandon Rome and move to Veii:

“On the authority of the Senate, we have added the Ludi Capitolini to the others that we regularly hold and founded a college [of priests] to superintend them”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 52: 11).

Whether or not these games really did date back to the late 4th century BC need not detain us: what is important is that:

✴the priestly collegio Capitolini still existed in 56 BC, when Cicero mentioned it in a letter to his brother (Letters to Quintus, 2: 5: 2); and

✴Livy’s record surely proves that the games over which they presided were held in honour of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (as one would expect).

No surviving source records that games known as the Ludi Capitolini were dedicated to Jupiter Feretrius.

Denarius Issued by ‘Marcellinus’ (ca. 50 BC)

At some time in the late Republic, a moneyer at Rome who identified himself as ‘Marcellinus’ issued the denarius illustrated above, on which he commemorated the achievements of a consular ‘Marcellus’ who must have been his ‘natural’ ancestor. Romans of this period would have recognised the ancestor in question as Marcus Claudius Marcellus, identified, if not by his portrait (which was presumably taken from his death mask), then by:

✴the reference to his five consulships (in 222, 215, 214, 210 and 208 BC);

✴the triskele, a symbol associated with the Sicilian city of Syracuse, which Marcellus had taken from an anti-Roman faction there as proconsul in 213 BC; and

✴the scene on the reverse, which depicted Marcellus carrying a military trophy into a temple.

Furthermore, the Romans of the period would have:

✴recognised the trophy as the armour that Marcellus had stripped from the Gallic commander Viridomarus, whom he had famously killed with his own hands at the battle of Clastidium in 222 BC; and

✴known that Marcellus had claimed this armour as spolia opima, and that the coin depicted him as dedicating it, as was his right, at the temple of Jupiter Feretrius on the Capitol.

I discuss the probable date of the issue of this coin below: for the moment, it is sufficient to proceed on the analysis of Michael Crawford (referenced below, at p. 88), which suggests that it was issued in ca. 50 BC.

Philip Hill (referenced below, at p. 27) observed that the portrayal of the temple on this reverse suggests that, by this time:

“... the building was tetrastyle, and probably of the Ionic order.”

It is alternatively possible, at least in principle, that the designer of the image had omitted the inner two of the columns of a hexastyle temple. However, this is unlikely, since the temple is known to have been a small one: Dionysius of Halicarnassus (see below), who presumably visited the site shortly after its Augustan restoration, commented that:

“... the ancient traces of [the earlier structure ?] still remain, of which the longest sides are less than fifteen feet”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 34: 1-3).

Unfortunately, this cannot be verified directly, since no archeological evidence of this temple on the Capitol has yet been found. Nevertheless, it does indeed seem likely that, in the late Republic, this was indeed a small tetrastyle temple.

Testimony of Cornelius Nepos (ca. 32 BC)

The earliest written evidence for the physical existence of the temple is in a surviving fragment of Cornelius Nepos’ biography of the antiquarian Titus Pomponius Atticus, which Nepos wrote shortly after Atticus’ death in 32 BC. In it, Nepos recorded that the triumvir Octavian (who became the Emperor Augustus in 27 BC) had been on excellent terms with Atticus, to the extent that, when Octavian was in Rome:

“... scarcely a day passed in which he did not write to Atticus, sometimes asking him something relating to antiquity ... Thus it was that, when the temple of Jupiter Feretrius, which Romulus had built on the Capitol, was unroofed and falling down through age and neglect, Octavian, on the suggestion of Atticus, took care that it should be repaired”, (‘Lives of Eminent Commanders: Titus Pomponius Atticus’, 20).

This is one of the few occasions on which we have hard evidence of an event related to the temple from the pen of someone who witnessed it. Furthermore, Nepos’ account was later corroborated: Augustus himself included its restoration in the account of his deeds that he wrote in the year before his death in 14 AD, (‘Res Gestae’, 19: 5). Unfortunately, no archeological remains of the temple are known.

Although Atticus, Nepos and their contemporaries could still see the remains an the old temple of Jupiter Feretrius on the Capitol, it seems that they were otherwise almost as much in the dark as we are. Roman tradition held that the much more important temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus that (perhaps literally) overshadowed it had been built by Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of Rome and dedicated at the dawn of Republic (traditionally in 509 BC). Thus, from the time that the Romans began to establish their foundation myths, the physical presence of the nearby, smaller and apparently older temple would have mandated its foundation in the regal period. It is therefore unsurprising that, when we first find the temple of Jupiter Feretrius in the surviving narrative sources (in a work by Ennius in the 2nd century BC discussed below), we learn that (as Nepos subsequently recorded in ca. 31 BC) it had been founded by Romulus. All we can really say is that there could well have been an archaic shrine on this site that was dedicated to the otherwise unknown Jupiter Feretrius, and that the temple that Octavian/ Augustus restored was probably built there before the end of the regal period.

Traditional Topography

As we have seen, Nepos considered that Romulus had built a temple the Jupiter Feretrius on the Capitol. In fact, this is an oxymoron: as Varro explained (in a work that was published in ca. 45 BC):

“... the Capitol is so named because here, when the foundations were being dug for the temple of Jupiter [Optimus Maximus], it is said that a human head (caput) was found. [Before that], this hill used to be called the Tarpeian Hill from the Vestal virgin Tarpeia, whom the Sabines killed ... and [who was] buried there [at the time of Romulus]. A reminder of her name is left behind: even now, [the cliff on the Capitol] is called the Tarpeian rock”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 5: 41, translated bu Roland Kent, referenced below, at p. 39).

This hill was slightly to the northwest of the walled settlement that he had founded on the Palatine:

✴He had already established an asylum for the refugees that he welcomed to Rome on a site:

“.... where, as you go down from the Capitol, you find an enclosed space between two groves”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 8: 5-6).

✴This asylum and its groves were in fact located in a saddle between the two peaks of the Capitol:

•the northern peak, which already housed the arx (citadel) that was under the command of Spurius Tarpeius, whose daughter Tarpeia would soon be killed there during a Sabine attack (‘History of Rome’, 1: 11: 6-9); and

•the southern peak (the ‘Capitol proper’).

This southern peal was presumably the location of the temple that Octavia/ Augustus restored in ca. 30 BC.

Augustan Sources

The temple of Jupiter Feretrius was probably the first of the many Roman temples that Octavian/ Augustus restored. He did so at a crucial moment in his career: his hold over Rome and the rest of Italy was still insecure, but he was nonetheless about to engage with Mark Antony and Cleopatra in the east in order to gain control of the entire Roman state. His restoration of the temple would therefore have had great propaganda value as he cultivated Roman support for what was, in effect, yet another civil war: as Alison Cooley (referenced below, 2009, at p. 188) observed, it would have:

“... assimilated [Octavian’s] role [in the Roman state] to that of [the temple’s] founder, Romulus.”

Furthermore, Octavian proclaimed himself to be divi filius, the son (by adoption) of the deified Julius Caesar, and thus, like him, a descendant of (the deified) Romulus. Added to these political drivers, the testimony of Nepos indicates a significant level of antiquarian interest leading up to its restoration. This was reflected in a re-telling of the temple’s traditional Romulean foundation.

Livy

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 110) argued that a revised edition of books 1-5 of Livy’s ‘History of Rome’ was published between 28 and 26 BC: if so, then Livy wrote his account of Romulus’ foundation of this temple while Octavian’s restoration of it was either in progress or recently completed. His account began at the time of Romulus’ abduction of the Sabine women, which led to war with some of the affected communities. The first attack came from the Latins of nearby Caenina and, in the battle that followed, Romulus:

“... routed their army, ... killed their king in battle and despoiled him [of his armour]”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 10: 3-4).

Romulus then quickly took Caenina itself, after which:

“... he led the victorious army [back to Rome]. Magnificent in action, he was no less eager to display [the evidence of] his achievements. To this end, he hung ... [the armour] of the dead dux (leader) on a ferculum (frame) made for the purpose and, having ascended the Capitol, set it down by an oak tree sacred to the shepherds”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 10: 5).

It seems likely that Livy envisaged the dead king’s armour as a trophy like the one depicted in the hands of Marcellus on the reverse of the coin illustrated at the top of the page.

We now come to the climax of Livy’s account:

“[Romulus] then marked out the boundary of a templum to Jupiter, to whom he gave an additional name [Feretrius], declaring:

‘I, Romulus, victor and king, fero (bring) the arms of a king ... to you, Jupiter Feretrius and, on this site, I vow to build a templum, which I have marked out in my mind, a place for dedicating the spolia opima, which later men, following my example, will bring here, having killed enemy kings and commanders’.

This was the origin of the first templum that was consecrated in Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 10: 5-7).

Robert Ogilvie (referenced below, at p. 72) argued that the language that Livy used for the dedication of the templum:

“... is sacral, being intended to recall the augural formula.”

Livy then described precisely how the gods preserved the importance of this sacred site over time:

“In later years, it has been the will of the gods that the words of [Romulus] ... should not be in vain when he declared that posterity would bring spoils to this place, [albeit that] the glory of that gift should not be debased by too many sharing it. [Indeed], so rarely have men had the good fortune of winning this honour that the spolia opima have been won [and dedicated at this temple] only twice since then, over so many years and so many wars”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 10: 7).

Site and Structure of the Templum

Livy’s use of the word templum indicates that he envisaged the inaugurated cult site as a sacred enclosure rather than as a roofed building: see for example, Beard, North and Price (referenced below, at p. 86). As we have seen, Romulus was believed to have drawn its boundaries near and perhaps around a sacred oak tree on the hill that was later known as the Capitol. It is possible that the early traditions envisaged that Romulus had attached the captured armour to the sacred oak tree and established his templum around it.

As we have seen, by 30 BC, there was a small temple on this site, albeit that it was by then:

“... unroofed and falling down through age and neglect”.

Livy is the only surviving source to record the building of a more substantial structure on this site after the time of Romulus: he recorded that:

“... the aedes of Jupiter Feretrius was enlarged in consequence of the brilliant successes in the war [of Ancus Marcius, the legendary fourth king of Rome]”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 33: 4).

Livy’s use of aedes here, as opposed to templum, suggests that he now envisaged a temple building that housed a statue of the god: see for example, Beard, North and Price (referenced below, at p. 78).

Significance of the Temple for Livy

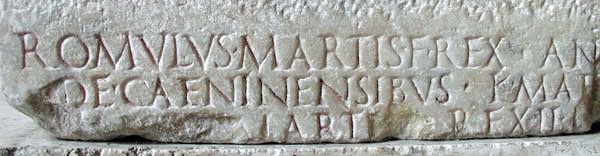

Opening lines of the fasti Triumphales (Musei Capitolini)

From ‘Mr Jennings’ on Flickr

Livy must have been aware of the tradition that Romulus triumphed at Caenina: for example, the fasti Triumphales, which were inscribed on stones that were on public display (probably on Augustus’ triumphal arch) soon after 19 BC, began by recording that:

“Romulus Martis F Rex An De Caeninensibus K Mar

[Romulus] Mart [is F] Rex II [.]”

“Romulus, son of Mars, [triumphed for the first time] over the Caeninenses ...

for the second time [.]”

[The next eleven lines are illegible]

As we shall see, there was a strand of tradition that equated this first Roman triumph with Romulus’ processional return to Rome carrying the arms of the king of Caenina, which culminated in his foundation of the first Roman temple. Frances Hickson Hahn (referenced below, at p. 95) pointed out that Livy’s account:

“... contains the primary features found in later triumph notices: the return of the army; the procession with commander; the display of captured spoils.”

She also noted (at p. 96) that:

“[Although Livy’s] description of the framework on which he hung the enemy armour is ... confusing for modern readers, ... the 1st century audience would have ... [seen] similar trophies displayed in triumphal processions and [depicted] on coins [as in the denarius illustrated at the top of the page].”

However, all that Livy actually said about Romulus’ return was that exercitu victore reducto (the victor led back the army). As Miriam Pelikan Pittenger (referenced below, at p. 33, note 2) pointed out:

“The word triumphus first appears [in Livy’s work at ‘History of Rome’], 1: 38: 3, for a celebration by Tarquinius Priscus, [the 5th king of Rome], over the Sabines.”

We must therefore assume that Livy’s omission was deliberate: for him, the significance of this small temple on the Capitol lay in the facts that:

✴it was the first ‘temple’ to be dedicated in Rome;

✴Romulus had founded it on an already sacred site at which he had also dedicated the spolia opima, the armour that he, a king, had taken from an enmey king with his own hands;

✴he had dedicated both the templum and the spolia opima to a new cult, that of Jupiter Feretrius ; and

✴the gods had ordained that future Roman generals whose virtus approached that of Romulus might win the honour of dedicating spolia opima here.

Propertius

The poet Propertius elegised the temple of Jupiter Feretrius in the penultimate poem (4:10) of Book 4 of the ‘Elegies’. The poem that followed it lamented the death of Cornelia, the wife of Aemilius Paullus, in 16 BC: since Propertius himself died soon after, Book 4 book was probably published at about this time. (The translations below are based on those of Vincet Katz, referenced below, at pp. 407-9, but there is also a convenient on-line translation in the website ‘Poetry in Translation’).

Opening ‘Statement of Aims’

The poem begins as Propertius ascends the Capitol from the Roman Forum:

“Now I begin, revealing the reason for

✴[the epithet of] Jupiter Feretrius; and

✴armaque trina (the three sets of armour [captured] ducibus tribus (from three enemy commanders).

I climb a steep path [to the Capitol], but the glory of it gives me strength ...”, (4: 10: 1-4).

By poetically ascending the Capitol, Propertius established that this elegy was focussed on the newly-restored temple of Jupiter Feretrius. His opening words declare that he is intent upon exploring:

✴why Romulus gave Jupiter the otherwise unknown epithet Feretrius; and

✴what could be learned from the fact that his temple was indelibly associated with three sets of armour taken from three enemy commanders.

Narrative ‘Meat’ of the Elegy

Propertius naturally began his poetic narrative with Romulus himself:

“You, Romulus, provide the example of the first such palm, when you returned laden with enemy spoils, ... [having] routed ... Acron of Caenina ... when he was attacking the gates [of Rome] ... Herculean Acron ... dared to hope for ... [spolia] from Quirinus’ shoulders. ... Romulus sees [Acron] testing his spear before the hollow turrets [of Rome] and attacks first, fulfilling his vows:

‘Jupiter, this victim, Acron, falls before you today.’

He vowed it, and [Acron] fell, as spoils, to Jupiter. The founder of the city and of its virtus (valour), was used to winning: ...”, (4: 10: 5-17).

This is the first time in our surviving sources that the king of Caenina is identified by name: he associated him with ‘Quirinus’, the name that Romulus was given on his subsequent deification: Acron claimed descent from a hero, while Romulus, the founder of Rome and of Roman virtus became one. Propertius then described the winning of the other two sets of armour from enemy commanders:

”[After Romulus]:

✴[Aulus Cornelius Cossus ] follows with the slaughter of Tolumnius [in 437, 428 or 426 BC] ... when it took some effort to be able to conquer Veii ... Poor old Veii: you were a kingdom then , ... but now [Romans] sow the fields over your bones. ... [Cossus and Tolumnius engaged in single combat]. The gods helped Latin hands: Tolumnius’ disecta cervix (cut neck) bathed Roman horses in its blood.

✴[Marcus Claudius Marcellus, in 222 BC came next: he], surrounded the enemy that had crossed the Rhine, when the the Belgic shield of the giant chieftain Virdomarus was brought here. ... As [Virdomarus] rushes out from the ranks, ... his curved torque fell ab incisa gula (from his slit throat).

Now spolia tria (three sets of spoils) are preserved in the temple”, (4: 10: 26-45).

Line 45 is the only line in which Propertius explicitly mentioned the temple. His emphasis in this section was rather on the three sets armour inside it, taken on three occasions:

✴when Acron fell, as a sacrificial victim, to Jupiter; and

✴when each of Tolumnius and Virdomarus had his throat cut.

As Myrto Garani (referenced below, at p. 113) observed, Propertius explicitly:

“... [substituted] the defeated generals for ... sacrificial animals.”

It is therefore surprising that Propertius:

✴failed to mention that the temple also housed the lapis silex, the sacred flint stone with which a fetial priest would cut the throat of a sacrificial pig in the ritual solemnisation of a peace treaty (as discussed in detail below); and

✴never referred to the three sets of arms that were apparently preserved in some form in the temple as the as spolia opima.

Propertius’ Etymology of Feretrius

Carolyn MacDonald (referenced below, at p. 201) observed that the opening line of this elegy defined:

“... Propertius’ project in distinctly Varronian terms, declaring:

‘Iouis incipiam causas aperire Feretri’ (I shall begin to lay bare the causes of Jupiter Feretrius),( 4.10.1).

The phrase causas aperire is not common in Latin literature, and it is strongly associated with Varro.”

She explained (at p. 194) that, in chapter 5 of his ‘De Lingua Latina’, Varro:

“... represents Rome as a topography constituted by words rather than by things: and these words not only retain traces of things past, they even make it possible to recover the pasts obscured by things present.”

Thus, for example, as we saw above, Varro recorded (at 5: 41) that the Capitoline hill was named for the caput humanum (human head) that was discovered during the construction of the the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in the time of Tarquins, and that, before then, it had been named for Tarpia, who had been buried there. However, Varro did not include what was then the derelict the temple of Jupiter Feretrius in his ‘tour’ of the Capitol, and it seems that Propertius now intended to do so in the Varronian manner.

True to his words, Propertius ended by doing what he had promised to do at the start of the elegy: explaining the origin of the epithet ‘Feretrius’:

“Now spolia tria (three sets of spoils) are lodged in the temple: causa Feretri (this is the reason for the epithet Feretrius):

✴because, with sure omen, dux ferit ense ducem (commander struck commander with a sword); or

✴perhaps the proud altar of Jupiter Feretrius is so called because victors ferebant (bore) on their shoulders the armour of those they vanquished”, (4: 10: 49-52).

In other words, Romulus dedicated the shrine and its altar to Jupiter in the form of either:

✴‘he for whom commander ferit (struck) commander’; or

✴‘he to whom commanders ferebant (bore) captured arms’.

These derivations, from ferire (to strike) and ferre (to bring) respectively, should probably be take together with:

✴the armaque trina (the three sets of armour and ducibus tribus (from three enemy commanders) of line 2; and

✴the spolia tria (three sets of spoils) of line 45.

Carolyn MacDonald (referenced below, at p. 207) observed that:

“... in his exuberant play upon both fere- and -tri [in his derivation of ‘FereTRIus’], Propertius outdoes even Varro in the proliferation of alternative causae.

She observed (at p. 207, note 59):

“There is no etymology of Feretrius in what survives of Varro, but it is possible that one or all of these derivations appeared in one of his treatises.”

I discuss the Propertius’ etymologies further below.

Significance of the Temple for Propertius

As Tara Welch (referenced below, at p. 1) observed, in this:

“... his fourth and final book, Propertius sets out a new artistic program: aetiological poetry celebrating Rome’s origins.”

Thomas Hendren (referenced below, at p. 6) similarly described it as:

“A professed aetiology of monumental Rome ...”

In other words, by explaining (albeit poetically) how some of the ancient Roman monuments had been conceived and what they had originally signified, Propertius ser out to explain what it had originally meant, and what it should still mean, to be Roman.

Carolyn MacDonald (referenced below, at p. 201) observed that:

“... although Propertius does identify some archaic monuments still standing in the Augustan city, his aetiologies for them invariably veer into etymology. The structures themselves are marginalised, and words provide far more access to the city’s past.”

The elegy under discussion here is an excellent example of this. Taking his lead from Varro, Propertius used the archaic epithet of Jupiter Feretrius and the three sets of enemy armour preserved in this temple to illuminate how:

✴Romulus, the founder of Rome and of Roman virtus, had established this cult for the dedication of the arms of King Acron;

✴Cossus had emulated him in virtus when he sacrificed Tolumnius and destroyed Veii at the start of the Roman conquest of Italy; and

✴Marcellus had followed this hallowed example when he he sacrificed Virdomarus and pushed the Belgic invaders back across the Rhine.

Nobody reading this elegy at the time of its publication in ca. 19 BC would have failed to recall that Augustus had rescued this temple in ca. 30 BC, immediately before his victory at Actium, particularly since Propertius had elegised this victory in a poem in which:

“... we will tell of [Augustus’] temple of Apollo Palatinus” (4: 6: 11).

It seems to me that, for Propertius, the significance of the restored temple of Jupiter Feretrius was that it bore witness to the achievements of the new Romulus, Augustus, at the dawn of a new age of peace.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

The Greek Dionysius helpfully prefaced his ’Roman Antiquities’ by informing his readers that:

“I arrived in Italy at the very time that [Octavian] put an end to the civil war, in the middle of the 187th Olympiad [30/29 BC]. I have lived at Rome from that time until the present day (a period of 22 years), learning the language of the Romans and acquainting myself with their writings. I have devoted myself during all that time to matters bearing upon my subject. I received orally some information from men of the greatest learning with whom I associated; and the rest I gathered from histories written by the approved Roman authors: Porcius Cato; Fabius Maximus; Valerius Antias; Licinius Macer; the Aelii; the Gellii; the Calpurnii; and many others of note. I set about the writing of my history [in Greek] on the basis of these works , which are like the Greek annalistic accounts”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 7: 2-3).

Thus, Dionysius’ work began to be published in ca. 7 BC. Interestingly, although he named many of his sources, here and in later passages, he did not name Livy in any of the parts of his work that survive, despite the fact that (as we have seen) Livy had published the first books of his ‘History of Rome’ not long after Dionysius’ arrival in the city.

Like Livy, Dionysius recorded that, soon after Romulus’ abduction of the Sabine women, he:

“... fought with [the king of Caenina] and, after killing him with his own hands, stripped him of his armour”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 33: 1-2).

However, in Dionysius’ account, Romulus then marched against the Antemnates, whom he also defeated (in an engagement not mentioned by Livy), following which:

“... he led his own army home, carrying with him the spoils of those who had been slain in battle and the [other] choicest part of the booty, as an offering to the gods ... Romulus himself came last in the procession, clad in a purple robe and wearing a crown of laurel upon his head. He rode in a chariot drawn by four horses so that he might maintain the royal dignity. The rest of the army ... followed, ... praising the gods ... and extolling their general in improvised verses. They were met by the citizens with their wives and children, who ... congratulated them upon their victory and expressed their welcome in every other way. When the soldiers entered the city, they found mixing bowls filled to the brim with wine and tables loaded down with all sorts of delicacies, which were placed before the most distinguished houses in order that all who pleased might take their fill. Such was the victorious procession ... that the Romans call a triumph, as it was first instituted by Romulus. But, in our day, the triumph ... has departed in every respect from its ancient simplicity”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 34: 1-3).

Dionysius then described the foundation of the temple, which he had probably seen, either before or during its restoration:

“After the [triumphal] procession and the sacrifice, Romulus built a small temple to Jupiter, whom the Romans call Feretrius, on the summit of the Capitol; indeed, the ancient traces of it still remain, of which the longest sides are less than 15 feet. In this temple, he consecrated the [armour] of the king of Caenina, whom he had killed with his own hands”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 34: 4).

He ended with what is almost an after-thought on the meaning of the epithet ‘Feretrius’:

“As for Jupiter Feretrius, to whom Romulus dedicated these arms, one will not be far from the truth if one calls him either:

✴Tropaiouchos (or Skylophoros, as some will have it); or

✴Hyperpheretês, since he excels all things and comprehends universal nature and motion”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 34: 4).

Significance of the Temple for Dionysius of Halicarnassus

The Temple and the Triumphal Procession

Unlike Livy, Dionysius characterised Romulus’ return to Rome after his defeat of the Caeninenses (and the of the Antemnates) as the first Roman triumphal procession. It is possible that he imagined that Romulus built the new temple at the place at which:

✴this triumphal procession had ended; and

✴the sacrifice that followed (presumably to Jupiter, in thanks for the victory) had been offered.

However, he did not explicitly say so. Furthermore, it is certain that he did not envisage the new temple as the culmination point of later triumphal processions, albeit that he (unlike any other surviving source) recorded that Romulus triumphed on two later occasions:

✴After Romulus suppressed a revolt at the Roman colony at Cameria:

“ ... he celebrated a second triumph. Out of the spoils, he dedicated a chariot and four [horses] in bronze to Vulcan and, near it, he set up his own statue with an inscription in Greek characters setting forth his deeds”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 54: 2).

Dionysius probably assumed that Romulus had dedicated the spoils to Vulcan at the Volcanal, an ancient shrine that was located at the foot of the Capitol, on the future site of the Roman Forum.

✴Romulus then defeated the Etruscan city-state of Veii, which opposed Rome’s control over nearby Fidenae. This victory culminated in:

“... the third triumph that Romulus celebrated, which was much more magnificent than either of the [other two]”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 55: 5).

In this case, Dionysius did not record the end-point of the triumphal procession.

In short, even if Dionysius imagined that Romulus’ first triumphal procession ended at the place where he would establish the temple of Jupiter Feretrius, he certainly did not characterise this temple as fulfilling the triumphal role that later fell to the Capitoline temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. It seems that, for Dionysius, the temple of Jupiter Feretrius was merely the small temple on the site at which Romulus had dedicated the armour of the king of Caenina to Jupiter Feretrius after his first triumph.

The Temple and the Arms of the King of Caenina

It is worth now revisiting Dionysius’ account of the events leading up to the dedication of the temple, stripping out the detail of the triumphal procession, in order to see how little he recorded about the arms of the king of Caenina:

✴During the battle:

“... when the king of Caenina met [Romulus] with a strong body of men, he (Romulus) fought with him and, after killing him with his own hands, stripped him of his arms”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 33: 2).

Unlike other authors, Dionysius gave no particular narrative weight to this example of Romulus’ virtus.

✴After Romulus’ victories:

“... he led his ... army home, carrying with him the spoils of those who had been killed in battle and the choicest part of the booty as an offering to the gods ... ”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 34: 1).

In this passage, Dionysius suggested neither:

•that the arms of the king featured prominently among the spoils of those who had been killed in battle; nor

•that Jupiter Feretrius featured among the gods to whom they were dedicated.

✴After the triumphal procession and the sacrifice:

“... Romulus built a small temple to Jupiter, whom the Romans call Feretrius, on the summit of the Capitol: indeed, the ancient traces of [the earlier structure ?] still remain, of which the longest sides are less than fifteen [Roman] feet. In this temple, he consecrated the spoils of the king of Caenina, whom he had killed with his own hand”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 34: 4).

Dionysius devoted most of this passage to recording the small size of the temple. It seems that he attached no particular significance to the fact that Romulus dedicated the arms of the king of Caenina in it (albeit that this is his second reference to the fact that Romulus had killed the king with his own hands).

It is particularly surprising that Dionysius did not designate these spoils as the spolia opima.

Furthermore, it seems that Dionysius made the same omission in his account of Cossus’ killing of the king of Veii in the late 5th century BC (assuming that the surviving fragment contains the whole of his account):

“... a Roman military tribune, Aulus Cornelius Cossus ... knocked [the king of Veii] from his horse and, ... after slaying him and stripping off his spoils, ... reduced those [of the enemy] who still held out ... to discouragement and fear”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 12: 5: 1-3).

In this account, he again failed to designate the arms of the dead enemy king as spolia opima. Furthermore, he apparently failed to record their dedication to Jupiter Feretrius.

Dionysius could hardly have been unaware of the Roman tradition of the spolia opima, which would have been recorded in many of his sources. He would also have seen images such as that on the reverse of the Roman coin illustrated at the top of the page, which represented Marcellus approaching the temple of Jupiter Feretrius carrying what was held to be the third set of spolia opima to be dedicated there, represented in a form that Dionysius would have considered to be a mobile tropaion (trophy). This iconography presumably led to his second suggestion for the meaning of the epithet “Feretrius: He ended with what is almost an after-thought on the meaning of the epithet ‘Feretrius’:

“Tropaiouchos (or Skylophoros, as some will have it)”;

which would have been based on similar epithets that the Greeks gave to Zeus. The website HelleniicGods.Org lists the most important of them, which include:

✴Tropaiouchos (or Tropaioukhos), literally ‘trophy-having’, probably in the sense given in the website: ‘to whom trophies are dedicated’; and

✴Tropaios, ‘he who turns, changes events, bestowing victory’.

Both of them derive from ‘tropaia’ (trophies of war. According to Kendrick Pritchett (referenced below, at p. 143) Dionysius’ alternative, ‘Skylophoros’, would have implied Zeus, ‘to whom the spoils of the [enemy] dead are dedicated’. However, the parallels with Jupiter Feretrius are not exact: neither Tropaiouchos nor Skylophoros implies a form of Zeus ‘to whom only the spoils of enemy commanders are dedicated’.

Beatrice Poletti (referenced below, at p. 173) pointed out that Dionysius’ lack of interest in the Romulean trophy is:

“... all the more peculiar, since [the ancient Greek practice of] setting the enemy’s spoils on a trophy ... would have fitted in with his constant ascription of Greek origins to Roman customs.”

We must therefore assume that Dionysius made a deliberate decision to ignore the Roman tradition of the spolia opima, for reasons about which we can only speculate.

Significance of the Temple for Dionysius of Halicarnassus: Conclusions

Dionysius did not mention that the temple of Jupiter Feretrius was probably the first temple to be dedicated in Rome, and he apparently found nothing remarkable about its dedication to Jupiter Feretrius. Furthermore, I argued above that his account suggests that he did not consider the temple to be either:

✴the focus of early Roman triumphs; or

✴of importance as the place where particularly important military trophies were dedicated.

The thing that seems to have struck him most about it was its small size. He was surely aware of its role in Augustan politics, but it is hard to escape the feeling that he wondered what all the fuss was about.

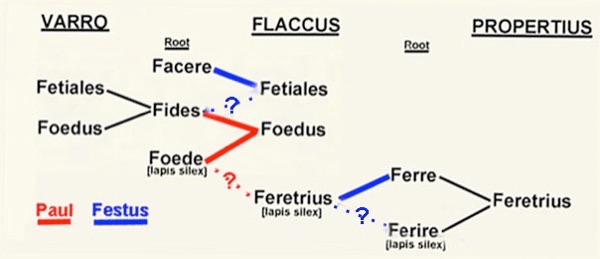

Marcus Verrius Flaccus

As we shall see, the grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus is our only surviving source for an etymology for ‘Feretrius’ that had nothing to do with the spolia opima. We do not know when he wrote his ‘De verborum significatu’, but we do know that he acted as tutor to Augustus’ grandchildren in the late 1st century BC, and that he died at an advanced age in ca. 20 AD. His lexicon is lost, but:

✴Festus preserved its contents in the form of a condensed summary in the 2nd century AD; and

✴missing parts of Festus’ work can be recovered from a summary of it that Paul the Deacon wrote in the 8th century AD.

The passages discussed below from both Festus and Paul are from the manuscripts edited by Wallace Lindsay (1913).

Two consecutive entries in Festus’ summary record that:

✴“Fetiales: are so called from ‘faciendo’ (making), because the right of making war and peace lies with them.

✴Feretrius: Jupiter is so-called from ‘ferendo’ (bringing), because he is thought to bring peace. From his templum, they take:

•the sceptre, by which they swear [oaths]; and

•the lapis silex [flint stone], by which foedus ferirent (they strike a treaty)”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 81 L, lines 14-8, translated by Wilson Shearin (referenced below, at p. 84).

These two entries are linked because the unspecified ‘they’ who took the sceptre and lapis silex from the temple belonged to the priestly collegium fetialium. From this, it seems that Flaccus believed that the Fetials kept two ritual objects connected with their peace-making functions in the temple of Jupiter Feretrius, the bearer peace.

As we have seen, Flaccus was not the earliest of the surviving sources for the etymology of Fertetrius: Carolyn MacDonald (referenced below, at p. 207, note 59) observed that:

“There is no etymology of Feretrius in what survives of Varro, but it is possible that one or all of [Propertius’] derivations appeared in one of his treatises.”

Varro may indeed have been the original source of the derivation of ‘Feretrius’ from ‘ferre’ or ‘ferire’: however, as she pointed out:

“... in his exuberant play upon both fere- and -tri [in his derivation of ‘FereTRIus’], Propertius outdoes even Varro in the proliferation of alternative causae.

Flaccus’ treatment was apparently less exuberant than that of Propertius:

✴Flaccus derived ‘Feretrius’ from ‘ferre’ (to bear), as did Propertius, in his second etymology. However:

•Propertius explained Jupiter Feretrius here as: ‘he to whom commanders ferebant (bore) armaque trina (the three sets of spolia opima that were preserved in the temple) taken ducibus tribus (from three enemy commanders); while

•for Flaccus, Jupiter Feretrius was simply Jupiter, the bearer of peace.

✴It is also possible that Flaccus alluded to Propertius’ first etymology, in which ‘Feretrius’ was derived from ‘ferire’ (to strike). However:

•Propertius explained Jupiter Feretrius here as: ‘he for whom commander ferit (struck) commander three times in order to win the three sets of spolia opima that were preserved in the temple;

•while, Flaccus explanation would have linked Jupiter Feretrius to the fetials’ striking of treaties and the ritual objects that they kept in the temple.

What is clear is that Flaccus differed fundamentally from Propertius in that:

✴while he did apparently deal extensively with the significance of the spolia opima and their dedication to Jupiter Feretrius (as set out in my linked page on the spolia opima).

✴he did not (as far as we can tell) offer any explanation of the epithet ‘Feretrius’ that featured the spolia opima.

On the basis of Festus’ summary, it seems that Flaccus started with the hypothesis that Jupiter Feretrius was the bearer of peace, and that he assumed that this was why the fetials housed their sceptre and the lapis silex in his temple.

Fetials and the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius

According to Roman tradition, Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome (traditionally 715-672 BC) established a number of priestly colleges, including the collegium fetialium. According to Varro, in a work published in 47-5 BC:

“Fetiales [are so-called] because they were in charge of public fides (faith) between people. It was through them:

✴that a war was judged to be just; and

✴[lacuna] that trust (fides) in the peace was established by foedera.

Before war was declared, some of them were sent to seek restitution [as an alternative to war]: even now, it is through them that fit foedus (a treaty is struck) ... : Ennius writes [in the 2nd century BC, that ‘foedus’] was pronounced fidus”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 5: 86, from the translation by Wilson Shearin, referenced below, at p. 83).

Thus, it seems that

✴Varro derived both ‘fetiales’ and ‘foedus’ from ‘fides’; and

✴at his time of writing, the fetials‘ primary role was the ritual of solemnisation that was performed when fit foedus (a treaty is struck)

John Rich (referenced below, 2011, at p. 204) pointed out that the surviving evidence (mostly from Livy):

“... records two quite distinct fetial pre-war rituals:

✴one to demand restitution (res repetere); and

✴the other to declare war (bellum indicere) through a spear-rite.

Since Varro did not mention the spear-rite, it may have become obsolete by his time. However, Octavian famously revived it in 31 BC: according to Cassius Dio, after the Senate had:

“... declared war on Cleopatra, [the senators] put on their military cloaks ... and went to the temple of Bellona, where they performed all the rites preliminary to war in the customary fashion, through [Octavian] as [a member of the collegium fetialium]. These proceedings, which were nominally directed against Cleopatra, were really directed against Mark Antony”, (‘Roman History’, 50; 4: 4).

Flaccus, who would have been about 25 at this time, might well have actually witnessed this very public event. He apparently recorded it in his lexicon: Paul the Deacon recorded that:

“Bellona is so-named because she is the goddess of bellum (war). A short column called the columna bellica stands in front of her temple, and it is customary to throw a spear over this column whenever the Romans declare war”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 30 L, lines 14-6, translated by Peter Aicher, referenced below, at p. 206).

Since it seems that Flaccus did not record that the fetials’ spear was kept with their sceptre and the lapis silex, it may have been kept elsewhere, perhaps in the temple of Bellona.

Flaccus’ Etymology of Foedus

We know that Flaccus and Festus originally addressed the etymology of “foedus’ because, although Festus‘ associated entry is absent from the surviving manuscripts, Paul the Deacon recorded that:

“Foedus [is] named, either:

✴from the fact that, in making peace, the victim is killed foede (shamefully, foully, hideously) ... ; or

✴because fides (good faith) is pledged in a foedus”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 74 L, lines 3-5, translation from Bill Gladhill, referenced below, at p. 53).

The second of these etymologies obviously reflects the Varronian passage above, although its presence in Paul’s summary suggests that Flaccus himself had also offered this as a possible root. In relation to the first:

✴we know from Livy (‘History of Rome’, 1: 24: 8) that Flaccus referred here to the fetial rite used in the solemnisation of foedera, in which a pig was sacrificed by being struck (presumably in the throat) with the lapis silex; and

✴another etymological passage by Varro also referred to this rite:

“The Greek name for the pig ... was [originally] θῦς from the verb θύειν (to sacrifice); for it seems that, at the beginning of making sacrifices, [the Romans] originally took the victim from the swine family. There are traces of this in ... [the fact] that, at the rites that initiate peace, foedus cum feritur, porcus occiditur (when a foedus is struck, a pig is killed)”, (‘On Agriculture’, 2: 4: 9, translated by William Hooper and Harrison Boyd, referenced below, at pp. 356-7).

Thus, in this second explanation, Flaccus suggested the foedus might have been derived from foede, because of the foul sacrifice in the associated ritual, when a (presumably squealing) pig was sacrificed by having its throat cut with the lapis silex, after which it presumably bled to death.

Significance of the Temple for M. Verrius Flaccus

Flaccus would surely have been able to verify the fact that the fetials’ sceptre and flint stone (the lapis silex) were kept in the temple, at least from the time of its restoration. Furthermore, it seems likely that Propertius also alluded to the presence of the lapis silex in his elegy on the temple discussed above. Thus, although Festus is the only surviving explicit source for this information, there is no reason to doubt that it was, indeed, the case. However, we cannot tell from Festus’ summary alone whether Flaccus followed a tradition in which the fetials’ association with the temple dated back to the regal period. In other words, it is possible that the practice began (or perhaps restarted after a ling interval) only Octavian’s restoration of the previously unroofed temple in ca. 30 BC: if so, then Flaccus would simply have noted that, after Octavian’s restoration of the temple of Jupiter, the bearer of peace, the fetials began to keep their sceptre and the lapis silex inside it.

On the other hand, we cannot rule out the existence of a Roman tradition in which this association dated back to either:

✴the foundation of the fetial college early in the regal period; or

✴the time of Ancus Marcius’ subsequent enlargement of the original Romulean shrine.

However, the problem here is that, while both Livy and Dionysius recorded both Romulus’ foundation of the temple and the existence of the fetial college in the early regal period, neither of them ever associated the temple with the fetials. Thus, for example, in Livy’s long account of the fetial solemnisation of the Romans’ treaty with Alba Longa, he recorded that the fetials took the sagmina (sacred herbs) from the Capitol, but he did not record that they took the lapis silex from the temple of Jupiter Feretrius. Furthermore Jupiter Feretrius did not feature in the oath sworn by the fetial designated as pater patratus, who:

“... cries:

‘Hear, Jupiter; hear, pater patratus of the Alban people: hear people of Alba: the Roman people will not be the first to depart from these terms, as they have been publicly rehearsed ... and clearly understood. If, by public decision, they should... [do so] with malice aforethought, then, on that day, may you, Jupiter, strike the Roman people as I shall now strike this pig: and may you strike with greater force, since your power and your strength are greater’.

When he had said this, he struck a pig with saxo silice (a flint stone). The Albans then pronounced their own forms and their own oath, by the mouth of their own dictator and priests”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 24: 8).

It cannot be argued from the silence of Livy and any other surviving source that there was no tradition that the fetials had kept their sceptre and lapis silex in the temple from an early date. Indeed, many scholars assume that this was case: thus, (to take only two of many examples):

✴Lawrence Springer (referenced below, at p. 28) asserted that:

“Jupiter with the epithet Feretrius was, from the earliest days, the god in whose name and under whose guidance treaties were established; and to his cult were assigned the priestly college of fetials, who executed the declaring of wars and the making of treaties”; and

✴Harriet Flower (referenced below, 2000, at p. 42) similarly asserted that the main purpose of the archaic temple of Jupiter Feretrius:

“... was closely associated with the rites of the fetiales, and was used as a repository for their sacred objects. The cult title Feretrius seems to refer directly to the fetiales and to their function of ratifying and regulating treaties.”

While this might be right (not least because the small size of the temple would have limited its use in the celebration of a public cult), it is important to bear in mind that the only evidence for this putative tradition is found in Paul’s etymology of foedus (above), which suggests that Flaccus originally addressed ‘fetiales’, ‘foedus’ and ‘Feretrius’ in consecutive entries. If so, then the logic of Flaccus original account would have been:

✴Fetiales: derived from:

•‘facere’ (to make), because the right of making war and peace lay with them (Festus); or

•possibly ‘fides’: although this root given by Varro is not found in surviving manuscripts of Festus’ epitome, it is found in Paul/ Festus (below) as a root of foedus;

✴Foedus: derived from:

•‘fides’, following Varro ( Paul/ Festus); or

•‘foede’, from the fact that, in striking a foedus, a fetial priest used the lapis silex to kill the victim in a foul way (Paul/ Festus).

✴Feretrius: derived from:

•‘ferre’ (to bear), because Jupiter Feretrius is thought to bring peace; or

•possibly from ‘ferire’ (to strike), with an explanation linking Jupiter Feretrius to the striking of foedera (Paul/ Festus) and the lapis silex (Festus).

In short:

✴If Paul’s entry indicates that Flaccus linked the etymologies of ‘fetiales’, ‘foedus’ and ‘Feretrius’ in the manner tentatively indicated on the diagram above, then we can reasonably assume that he relied on a tradition in which the fetials, at least in their peace-related roles, had had a close association with temple of Jupiter Feretrius that dated back to their foundation.

✴However, if we ignore the conjectures underlying the dotted lines in the diagram, then all was can say is that Flaccus derived ‘Feretrius’ from ‘ferre’, explaining that Jupiter Feretrius was the bearer peace, which explained why, at his time of writing, the fetials kept two ritual objects connected with their peace-making functions in his temple.

Other Sources for the Etymology of Feretrius

Feretrius from Ferire

Propertius’ first etymology had Jupiter Feretrius as ‘he for whom commander ferit (struck) commander on three occasions’. Plutarch followed this tradition about a century later: in his account of the life of Romulus, he recorded that:

“... the trophy [made from the arms of the king of Caenina] was styled a dedication to Jupiter Φερετρίου (Feretrius), so named from the Roman word ‘ferire’ (to strike); for Romulus vowed to strike his foe and overthrow him”, (‘Life of Romulus’, 16: 5-7).

However, he offered three etymologies for Feretrius in his account of the life of Marcellus:

“The god to whom the spoils were dedicated was called Jupiter Feretrius:

✴because the trophy was carried on a ‘phéretron’; this is a Greek word, and many such were still mingled at that time with the Latin [see below]; or

✴... as the wielder of the thunder-bolt, from the Latin ‘ferire’, meaning to strike; or

✴ ... [from] the blow that one gives an enemy, since, even now, when [the Romans] are pursuing their enemies in battle, they exhort one another with the word ‘feri,’ which means strike!”, (‘Life of Marcellus’, 8: 3-5).

The last two of these still derive Feretrius from ferire, but it seems that Plutarch gave free rein to his imagination in the accompanying explanations.

Feretrius from Ferre

Propertius’ second etymology had Jupiter Feretrius as ‘he to whom three commanders ferebant (bore) captured arms’. There might well have been an earlier tradition for this derivation from ferre, (to bear), as evidenced from the passage below by Livy:

“[Romulus] then marked out the boundary of a templum to Jupiter, to whom he gave an additional name [Feretrius], declaring:

‘I, Romulus, victor and king, fero (bring) the arms of a king ... to you, Jupiter Feretrius and, on this site, I vow to build a templum, ... a place for dedicating the spolia opima, which later men, following my example, will bring here, having killed enemy kings and commanders’”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 10: 5-6).

For Livy, as for Propertius, the obvious object of ferre (i.e., the things that were borne) were the spoils of enemy commanders. As we have seen, the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus also gave ferre as the root of Feretrius, but this time for Jupiter Feretrius as the bearer of peace.

Livy might have alluded to a variant of this etymological tradition in a slightly earlier passage relating to Romulus’ dedication of the spolia opima: after he killed the king of Caenina, Romulus:

“... hung ... [the dead king’s armour] on a ferculum made for the purpose and, having ascended the Capitol, set it down by an oak tree sacred to the shepherds”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 10: 5).

The word ferculum seems to derive from ferre and is translated by C. Lewis and C. Short as:

“[A thing on which something] is carried or borne: a frame, barrow, litter or bier for carrying [spolia], the images of the gods, etc., in public processions.”

In the first of three etymologies that Plutarch put forward in his life of Marcellus (above), he suggested that:

“The god to whom {Marcellus] dedicated [the armour of Virdomarus] was called Jupiter Feretrius because the trophy was carried on a φέρετρον (phéretron; from phérō: ‘I carry’): this is a Greek word, and many such were still mingled at that time with the Latin”, (‘Life of Marcellus’, 8: 4).

This suggests that Livy and Plutarch knew of a tradition in which ‘Feretrius’ was derived from ferre via ferculum.

Julius Caesar

Michael Crawford (referenced below) established from tabulated data (at pp. 84-5) relating to coin hoards that Marcellinus’ coins had been issued in ca. 50 BC: Crawford himself dated them to precisely 50 BC, and observed (at p. 460) that:

“The issuer is presumably P. Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus, the quaestor of 48 BC.”

This quaestor is known only from Caesar’s account of his victory over Pompey at Dyrrachium in 48 BC, in which he referred to the part played by his:

“... quaestor Lentulus Marcellinus, posted with the Ninth Legion ...”, (‘Civil Wars’, 3: 62).

Kamil Kopij (referenced below, at p. 176), who accepted that Marcellinus was a supporter of Caesar, pointed out that his coins would thus have been among the first issued in Rome after Caesar had gained control of Rome in 49 BC. He therefore considered the possibility that they had been issued in 49 BC, in which case, this denarius would have represented a political response to a denarius (RRC 445/1) that was issued by the Pompeian consuls of that year, L. Lentulus and C. Claudius Marcellus (Maior), from a military mint used to fund the Pompeian army in Apollonia and Asia. For our purposes, it is enough to note that its political importance probably extended beyond the celebration of Marcellinus’ ancestry and the enhancement of his personal career prospects: Caesar might well have appointed Marcellinus as a triumvir monetalis in this early stage of the civil war precisely in order to claim his ancestor Marcellus for the Caesarian cause. If so, then the depiction of the temple of Jupiter Feretrius on Marcellinus’ denarius would have been a useful but probably secondary consequence of Caesar’s propaganda objectives, albeit that the fact that Caesar claimed descent from Romulus probably added to the propaganda value of this image.

Read more:

B. Poletti, “Dionysius of Halicarnassus and the 'Founders' of Rome: Depicting Characters in the Roman Antiquities”, (2018, thesis of the University of Alberta

C. MacDonald, “Rewriting Rome: Topography, Etymology and History in Varro de Lingva Latina 5 and Propertius Elegies 4”, Ramus, 45:2 (2016) 192–212

B. Gladhill, “Rethinking Roman Alliance”, (2016) Cambridge

F. Hickson Hahn, “Livy's Liturgical Order: Systematisation in the History”, in:

B. Mineo (Ed.), “A Companion to Livy”, (2015) Chichester

W. Shearin, “The Language of Atoms: Performativity and Politics in Lucretius' ‘De Rerum Natura’”, (2015) Oxford

J. Rich, “The Fetiales and Roman International Relations”, in:

J. H. Richardson, and F. Santangelo (Eds), “Priests and State in the Roman World”, (2011 ) Stuttgart, at pp. 187-242

A. Cooley, “Res Gestae Divi Augusti: Text, Translation and Commentary”, (2009) Cambridge

T. Hendren, “Unraveling Roman Identity: Propertius, Callimachus and Elegies 4: 9-11”, (2009), thesis of the University of Florida

M. Pelikan Pittenger, “Contested Triumphs: Politics, Pageantry and Performance in Livy's Republican Rome”, (2008) Berkeley, Los Angeles and London

M. Garani, “Propertius' Temple of Jupiter Feretrius and the Spolia Opima (4.10): a Poem not to be Read?”, L’ Antiquité Classique, 76 (2007) 99-117

T. Welch, “The Elegiac Cityscape: Propertius and the Meaning of Roman Monuments”, (2005) Columbus, OH

P. Aicher, “Rome Alive: A Source-Guide to the Ancient City: Volume I”, (2004) Waucunda, ILL

V. Katz (translator), “Complete Elegies of Sextius Propertius”, (2004) Princeton, NJ

H. Flower, “The Tradition of the Spolia Opima: M. Claudius Marcellus and Augustus”, Classical Antiquity, 19:1 (2000) 34-64

M. Beard, J. North and S. Price, “Religions of Rome: Volume II: a Sourcebook”, (1998). Cambridge

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume I: Book VI”, (1997) Oxford

H. Flower, “Fabulae Praetextae in Context: When Were Plays on Contemporary Subjects Performed in Republican Rome?”, Classical Quarterly, 45:1 (1995) 170-90

S. M. Goldberg, “Epic in Republican Rome”, (1995) New York and Oxford

W. K. Pritchett, “The Greek State at War: Part V”, (1991) London

S. J. Harrison, “Augustus, the Poets, and the Spolia Opima”, Classical Quarterly, 39:2 (1989) 408-14

P. Hill, “The Monuments of Ancient Rome as Coin Types”, (1989) London

R. M. Ogilvie, “Commentary on Livy: Books.1-5”, (1965) Oxford

L. Springer, “Cult and Temple of Jupiter Feretrius”, Classical Journal, 50:1 (1954) 27-32

R. Kent (translator), “Varro: On the Latin Language, Volume I (Books 1-7) and Volume II (Books 8-10 and Fragments”, (1938) Cambridge, MA

E. H. Warmington (translator), “Remains of Old Latin, Volume II: Livius Andronicus. Naevius. Pacuvius. Accius”, (1936) Cambridge, MA

E. H. Warmington (translator), “Remains of Old Latin, Volume I: Ennius. Caecilius”, (1935) Cambridge, MA

W. D. Hooper and H. Boyd (translators), “Cato: Varro: On Agriculture”, (1934) Cambridge, MA

Linked pages: Collegium Fetialum; Spolia Opima; Temple of Jupiter Feretrius

Return to Temples

Return to Romans