Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Aftermath of the First Punic War (214 BC)

Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Aftermath of the First Punic War (214 BC)

Fall of Falerii (241 BC)

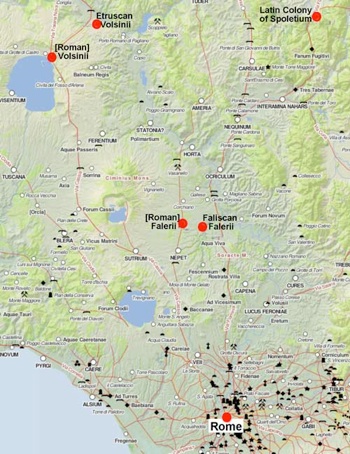

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

The Faliscan town of Falerii, some 60 km north of Rome, had had sought, and probably received, a foedus with Rome in 343 BC, impressed (it was said) by the Romans’ success in the First Samnite War. It had briefly joined the revolt of the neighbouring Etruscans in 293-2 BC, towards the end of the Third Samnite War:

✴Sp. Carvilius Maximus, after his campaign in Samnium in 293 BC, marched into Etruria and:

“... [made] preparations to attack [the now-unknown town of] Troilum in Etruria. He allowed 470 of its wealthiest citizens to leave the place after they had paid an enormous sum by way of ransom; and he took by storm the town with the rest of its population. Thereafter, he took five forts that occupied positions of great natural strength, in actions in which the enemy lost 2,400 killed and 2,000 prisoners. The Faliscans sued for peace, and he granted them a truce for one year on condition of their supplying a year's pay to his troops, and an indemnity of 100,000 asses f=of bronze coinage”, (‘‘History of Rome’’, 10: 46: 10-12).

✴Zonarus recorded that, in the following year:

“The Romans ... sent out Carvilius [as legate] with [the new consul, Junius Brutus [Scaevola, to continue the campaign against the Faliscans]. Brutus worsted the Faliscans and plundered their possessions, as well as those of the other Etruscans”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 8: 1: 10, search in this link on ‘Carvilius’).

Nothing in our surviving sources suggests that the Faliscans subsequently caused problems. However, somewhat surprisingly, the ‘fasti Triumphales’ record that, within a few months of the end of the First Punic War in 241 BC, both consuls, A. Manlius Torquatus Atticus and Q. Lutatius Cerco, celebrated triumphs “over the Faliscans”. A number of our surviving sources support this

✴Cassius Dio:

“... the Romans made war upon the Faliscans and [the consul] Manlius ravaged their country. ... he was victorious and took possession of ... half of their territory. Later on, the original city, which was set upon a steep mountain, was torn down and another one was built, easy of access”, (‘Roman History’, 8: 18).

✴Eutropius:

“[The consuls] Lutatius and Manlius ... made war upon the Falisci ... and [were victorious] within 6 days: 15,000 of the enemy were slain and peace was granted to the rest, but half their land was taken from them”, (‘Breviarium’’, 2: 28)..

✴Polybius:

“[Immediately after] the confirmation of the peace [with Carthage, the Romans engaged in] war against the Faliscans. They [captured] Falerii after only a few days' siege”, (‘Histories’, 1:65).

✴Livy:

“When the Faliscans revolted, they were subdued on the 6th day, and their surrender was accepted”, (‘Periochae’, 20: 1).

Further evidence of this victory comes in the form of a bronze cuirass of unknown provenance that is now in the Getty Museum, Malibu, which carries an inscription (AE 1998, 0199) that reads:

Q(uinto) Lutatio C(ai) f(ilio) A(ulo) Manlio C(ai) f(ilio)/ consolibus Faleries capto(m?)

Jean-Louis Zimmerman (referenced below, at p. 40) dated the cuirass to the second half of the 4th century BC. He suggested (at p. 41) that it had been an heirloom that had been worn by a Faliscan cavalryman who had been killed in the battle of 241 BC, and concluded (at p. 42) that:

“The inscription might have been engraved for a Roman who was entitled to the remains of an opponent whom he had killed in single combat” (my translation).

Thus, there can be no doubt that both consuls successfully attacked Falerii in 241 BC and killed a number of its defenders. However, the cause of this one-sided war are completely obscure. It seems unlikely that the Faliscans would have chosen to revolt at precisely the time that the Romans established their supremacy over the mighty Carthaginians. A more likely scenario is thus that the Romans mounted a surprise attack on Falerii, which would account for their rapid success in taking the almost impregnable settlement. Eutropius and Cassius Dio agreed that the Romans had then confiscated half the territory of Falerii. However:

✴Eutropius related that the survivors at Falerii were granted peace in 241 BC; while

✴according to Cassius Dio:

“Later on [i.e., at an unknown date after the battle], the original city, which was set upon a steep mountain, was torn down and another one was built, easy of access.”

It is often assumed that the situation at Falerii was analogous to that at the original Etruscan city of Volsinii, where the inhabitants were forcibly removed to a less defensible site in 264 BC. It is certainly true that the old city (located at modern Civita Castellana) was largely abandoned at about this time, although a number of its sanctuaries remained in use until ca. 100 BC (see , for example, the recent paper by Nicoletta Cignini, referenced below). However, this model of forced removal is not supported by the archeological evidence from the so-called Falerii Novi, some 6 km to the west. Simon Keay and Martin Millett (referenced below, at p. 364) described its location:

“... on the line of the Via Amerina ... The position of the town is such that both Falerii Veteres and Monte Soracte, sacred to Apollo, were visible to the east ... [It was] conceived as an artificially landscaped plateau that was enclosed within high walls ... in order to present a monumental facade to visitors approaching along Via Amerina to the south.”

They also note (at p. 365) the existence of a processional way from Falerii Novi to the:

“... still-functioning sanctuary of Juno Curitis at the foot of the abandoned site of Falerii Veteres.”

Keay and Millet expressed the view (at p. 364) that:

“Falerii Novi is best understood as a re-foundation, expressed in terms of the architectural language of Roman colonies while consciously incorporating key points of reference to the earlier Faliscan settlement.”

Foundation of the Colony of Spoletium (241 BC)

According to Velleius Paterculus (ca. 19 BC - 31 AD):

“Spoletium [was formed] three years [after the consulship of Torquatus and Sempronius [i.e. in 241 BC], in the year in which the Floralia were instituted” (‘Roman History’, 1:14:8) .

The colony, which was assigned to the Horatia tribe after the Social War, received a substantial ring of walls soon after colonisation that incorporated part of the original walls of the much smaller Umbrian settlement.

According to Paolo Camerieri and Dorica Manconi (referenced below, at p. 19):

“The founding of the Latin colony of Spoletium probably constituted the completion of the programme of Romanisation of the northern Sabina that had been undertaken by M’ Curius Dentatus. [This process] had begun with the founding of the Latin colony of Narnia, and continued with the establishment of the prefectures of Roman citizens at Amiternum, Reate and Nursia ... Having regard to the location of the colony [of Spoletium] ..., it undoubtedly provided a secure base for the final Romanisation of Umbria and central Italy, complimented 20 years later by the construction of Via Flaminia ...” (my translation).

Read more:

Cignini N., “Civita Castellana (VT): Indagini Archeologiche di Emergenza nel Duburbio di Falerii Veteres”, Journal of Fasti Online (2016)

Camerieri P. and Manconi D., “Le Centuriazioni della Valle Umbra da Spoleto a Perugia”, Bollettino di Archeolgia Online, (2010) 15-39

Keay S. and Millett M., “Republican and early Imperial Towns in the Tiber Valley”, in:

Cooley A. E. (editor), “A Companion to Roman Italy”, (2006), at pp. 357–77

Zimmermann J-L, “La Fin de Falerii Veteres: Un Temoignage Archeologique”, J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, 14 (1986) 37-42

Return to Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)