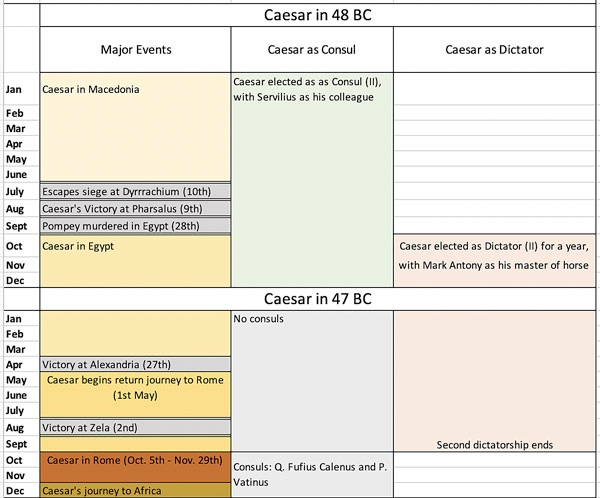

Dates in the table above are based on the paper by

John Ramsey and Kurt Raaflaub (referenced below, at pp. 187-97)

Summary

The entry for 48 BC in the Augustan fasti Capitolini can be completed as:

-

[Consuls]: C. Julius C.f. C.n. Caesar II ; P. Servilius [P.f. C.n. Vatia Isauricus]

As we have seen, Caesar recorded that he was elected to his second consulship in 48 BC:

-

“... this [was] the year in which it was legally permissible for [me] to be consul [again]”, (‘Civil War’, 3: 1: 1, translated by Cynthia Damon, referenced below, at p. 193).

He had finally achieved his most important political objective, albeit by unorthodox procedure at the end of an illegal march on Rome that had culminated in civil war.

Political orthodoxy was similarly in abeyance at Pompey’s camp at Thessalonica. Although Pompey himself had operated as primus inter pares for most of 49 BC, he was given overall command of the senatorial armies towards the end of the year: thus, Caesar recorded that the envoys that Pompey sent to him at Oricum in Epirus at the start of 48 BC (see below) had stressed that they had no mandate to negotiate, since:

-

“... in accordance with the recommendation of the advisory council, Pompey has been entrusted with the totality of the war and everything else”, (‘Civil War’, 3: 16: 4, translated by Cynthia Damon, referenced below, at p. 217).

Thus, as Cassius Dio observed, during the consular year of 48 BC:

-

“... the Romans had two sets of magistrates, contrary to custom ... :

-

✴The people [who remained in Rome] had chosen as consuls Caesar and Servllius, along with praetors and all the other officers required by law.

-

✴Those [at Pompey’s camp] in Thessalonica had made no such appointments, although there were, by some accounts, about 200 senators there, as well as the consuls [of 49 BC]. ... They had not appointed new magistrates [for 48 BC] because the consuls had not proposed the lex curiata: instead, they employed the same officials as before, merely changing their names and calling some proconsuls, others propraetors, and yet others proquaestors”, (‘Roman History’, 41: 43: 1-).

He summarised the resulting situation as follows:

-

“... the magistrates of the two parties [held office] in name only. In reality, it was Pompey and Caesar who were supreme; they bore the legal titles of proconsul and consul respectively or the sake of appearances,. However, their acts were not those that these offices permitted, but rather whatever they themselves pleased”, (‘Roman History’, 41: 43: 4).

Any pretence of a ‘shadow’ Roman administration in the east ended with:

-

✴Caesar’s definitive victory at Pharsalus on 9th August; and

-

✴Pompey’s murder in Egypt on 28th September.

The truth of thesis became manifest in Rome when Caesar’s freedman Diochares reached Rome carrying Pompey’s signet ring, letters from Caesar and presumably his orders for the coming year. It was about this time that Caesar was appointed to his second dictatorship, which was designated to last for a year: in my view, Caesar had probably adopted this and other unorthodox arrangements because he was unsure when he would finally return to Rome.

Caesar’s 2nd Consulship (48 BC)

Sites of the battles in 48-7 BC): Dyrrachium (9th July 48 BC); Pharsalus (9th August48 BC);

Nicopolis : defeat of Cn. Domitius Calvinus (8th December 48 BC);

Alexandria (27th March 47 BC); and Zela (2nd August 47 BC)

Adapted from John Carter (referenced below, 2008, Map 4)

Chronology based on John Ramsey and Kurt and Raaflaub (referenced below, at pp. 198-205)

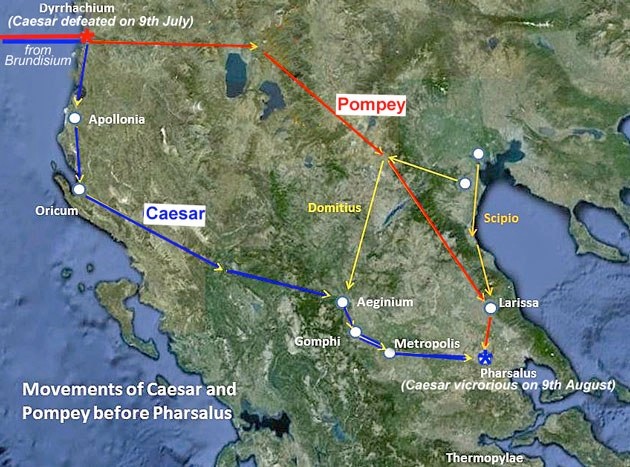

Caesar’s Victory at Pharsalus (9th August)

Adapted from Mike Anderson’s Ancient History Blog

Caesar had mustered his army and his fleet at Brundisium by the start of the consular year (although, by this time, the calendar was very much out of synchronisation with the seasons, and it would have been in November on the more meaningful calendar that Caesar would introduce in 45 BC - see John Ramsey and Kurt Raaflaub, referenced below, at p. 197). He managed to cross to Epirus with part of his army in January, but the combination of winter weather and Pompey’s naval blockade of Brundisium meant that Mark Antony (who was to accompany Caesar, probably as legate) could not make the crossing with the rest of his army until April.

The war began badly for Caesar at Dyrrhachium, where according to he own account, he:

-

“... lost 960 soldiers in the two battles of this one day [ 9th July]”, (‘Civil War’, 3: 71: 1, translated by Cynthia Damon, referenced below, at p. 293).

However, he was able to escape with the rest of his army, and reached his base at Apollonia on July 15th: as he recorded, he:

-

“... had go to Apollonia to settle the wounded, pay the army, encourage the allies, and garrison various cities. But the time he spent on these matters was limited by his need for haste”, (‘Civil War’, 3: 78: 1-2, translated by Cynthia Damon, referenced below, at p. 303).

Caesar then continued to Thessaly. Cn. Domitius Calvinus, the Caesarian governor of Asia Minor, joined Caesar at Aeginium and Caesar then established his camp near Pharsalus on 1st August.

Pompey,took the Via Egnatia to Larissa, where he was joined by Q. Caecilius Metellus Scipio, the Pompeian governor of Syria. According to Plutarch, Pompey:

-

“... left behind him at Dyrrhachium a great quantity of arms and stores, and many kindred and friends. He appointed [M. Porcius Cato] as their commander and guardian, with 15 cohorts of soldiers, because he both trusted and feared [Cato]: for, he thought that Cato would be his surest supporter in the event of defeat but that, if he were present [at the anticipated battle], he would not permit him to manage matters as he chose in the event of a victory. Many prominent men were also ignored by Pompey and left behind at Dyrrhachium with Cato”, (‘Life of the Younger Cato’, 55: 1-2).

As we shall see, these ‘prominent men’ included Cicero and Varro.

Both armies engaged at Pharsalus, where Caesar emerged victorious: the early imperial fasti recorded the annual celebration of this victory on 9th August (see, for example, Gian-Luca Gregori et al., referenced below, at p. 141). According to Appian:

-

“ The losses of Italians on each side ... were as follows:

-

✴in Caesar's army, 30 centurions and 200 legionaries, or, as some authorities have it, 1200;

-

✴on Pompey's side: ten senators, among whom was L. Domitius [Ahenobarbus], the man who had been sent to succeed Caesar himself in Gaul [in 49 BC]; and about 40 distinguished knights. Some exaggerating writers put the loss in the remainder of his forces at 25,000, but Asinius Pollio, who was one of Caesar's officers in this battle, records the number of dead Pompeians found as 6,000.

-

Such was the result of the famous battle of Pharsalus”, (‘Civil Wars’, 2: 82).

RRC 452

Aureus (RRC 452/1) and silver denarius (RRC 452/2) issued by Caesar: 48-7 BC

Obverse: LII: head of goddess wearing an oak-wreath and diadem

Reverse: CAESAR: trophy with Gallic shield and carnyx, in reference to earlier victories over non-Roman enemy

Probably produced at a military mint travelling with Caesar’s army

The coins illustrated above belong to an issue that bore the obverse inscription LII, which was almost certainly a reference to Caesar’s age: his 52nd birthday fell on 13th July 48 BC. As Michael Crawford (referenced below, at p. 467) pointed out (and pace the CRRO database used for the links above), they were almost certainly produced by one of Caesar’s military mints. Olga Liubimova (referenced below) pointed out, Caesar paid has army at Apollonia at about this time, and:

-

“[By] ordering to strike his age on coins, Caesar did not aim to emphasise the legality of his second consulship [as is sometimes suggested. He more probably] wanted to tighten his personal ties with his soldiers.”

It seems to me that the silver denarii were very probably first produced at Apollonia in July 48 BC for this purpose, and the allusions to the earlier victories in Gaul would have been intended to boost morale.

However, the aurei are much rarer and also much more remarkable: as this extract from the CRRO database illustrates, this was only the second coin of this denomination to be issued since RRC 381/1, which was issued for Sulla as dictator in 80 BC. (As Kamil Kopij, referenced below, pointed out, the other earlier aureus, RRC 402/1 was issued by Pompey issued as pro consul: Pompey was proconsul almost continuously from 76 BC and, while his aurei are usually dated to 71 BC, they could actually have been issued in almost any year in the period 76 - 48 BC). It seems to me that RRC 452, which was the first of six aurei minted by or for Caesar, was probably minted to commemorate his victory at Pharsalus.

Aftermath of the Battle of Pharsalus

Pompey’ Flight

Journeys of Pompey and Caesar from Pharsalus to Egypt, adapted from Wikimedia

See John Ramsey and Kurt and Raaflaub (referenced below, at pp. 199-200) for the chronology of the journeys, according to which, Pompey was murdered on arrival at Pelusium on 28th September and

Caesar arrived at Alexandria on 2nd October

According to Caesar, he decided that, after his victory:

-

“... he should leave all else aside and pursue Pompey wherever he went after his escape, to make it impossible for him to procure other troops and renew the war”, (‘Civil War’, 3: 102: 1, translated by Cynthia Damon, referenced below, at p. 337).

He then recorded that:

-

“Pompey spent one night at anchor ... at Amphipolis ... Learning of Caesar’s approach, he left that location and, within a few days ,came to Mytilene, [on the island of Lesbos]. After being delayed two days by weather and acquiring some additional fast vessels, he went on to Cilicia and thence to Cyprus. There, he learned that the people of Antioch ... had ... seized the citadel in order to keep him out ... The same thing had happened to L. [Cornelius] Lentulus, the previous year’s consul, at Rhodes, and to the ex-consul P. Lentulus [Spinther], and some others. These men were following Pompey after their escape and, when they reached Rhodes, they were not received into the city or the harbour. ... Pompey, when he understood the situation, dropped the plan of approaching Syria. ... [Instead], ... he went to Pelusium”, (‘Civil War’, 3: 102: 14 - 103: 2, translated by Cynthia Damon, referenced below, at p. 339-41).

As Pompey approached Alexandria on 28th September, the young King Ptolemy XIII invited him to land and sent out a small boat to receive him.

-

✴According to Caesar:

-

“... Pompey boarded the tiny vessel with a few of his friends. There he was killed by Achillas and Septimius, [the advisors of the young king]. Ptolemy also laid hands on [L. Cornelius Lentulus (cos 49 BC), who] was killed in prison”, (‘Civil War’, 3: 104: 2-3, translated by Cynthia Damon, referenced below, at p. 343).

-

✴According to the surviving summary of the now-lost Book 112 of Livy’s ‘History of Rome’:

-

“... he was [murdered] on the orders of king Ptolemy [XIII]... by Achillas, [the young king’s guardian] ... Pompey's wife Cornelia and his son Sextus Pompeius escaped to Cyprus”, (Periochae’, 112: 2-4).

Other Pompeian Casualties at Pharsalus

As we have seen, L. Cornelius Lentulus was executed in an Egyptioan prison before Caesar’s arrival in Alexandria. His erstwhile colleague as consul, C. Claudius Marcellus, who had shared the command of Pompey’s fleet, now disappears from our surviving sources: the precise date of his death is unknown, but, in a speech that he delivered in the Senate on 20th March 43 BC, Cicero deeply regretted that:

-

“... the Republic could [not] have kept the two consuls [of 49 BC], great patriots both”, (‘Philippics’, 13: 14, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 2010, at Vol. II, p. 263).

He also regretted the loss of:

-

✴L. Domitius Ahenobarbus (whose death at Pharsalus was noted above); and

-

✴M. Claudius Marcellus (cos 50 BC): according to Elaine Fantham (referenced below, at p. 209), this Marcellus, the cousin of the consul of 49 BC:

-

“... had withdrawn to the free city of Mytilene on Lesbos and was passing his years in scholarly retirement.”

-

Caesar eventually pardoned him, but he was murdered at Athens in May 45 BC, when he was finally en route for Rome.

Cato, Cicero and Varro at Dyrrhacium after Pharsalus

As we have seen, Pompey had left Cato in command at Dyrrhachium when he left for Pharsalus. Cicero described the situation there at the time of Pompey’s defeat:

-

“C. Coponius ... came to [the Pompeian camp] at Dyrrachium when he was in command of the Rhodian fleet as praetor, and [relayed] a prediction made by a certain oarsman from one of the Rhodian quinqueremes. The prediction was that, in less than 30 days, Greece would be bathed in [Pompeian] blood; Dyrrachium would be pillaged; its defenders would flee to their ships ... This story... caused great alarm to those cultured men, M. Varro and M. Cato, who, [like Cicero himself], were at Dyrrachium at the time. In fact, a few days later [Titus] Labienus reached Dyrrachium in flight from Pharsalus, with the news of the loss of the army. The rest of the prophecy was soon fulfilled”, (‘On Divination’, 1: 68translated by William Falconer, referenced below, 1: 299-301).

According to Plutarch, at this point:

-

“... Cato resolved that:

-

✴if Pompey were dead, he would take those who were still with him back to Italy, but would himself live in exile, as far as possible from the tyranny of Caesar; but

-

✴if, on the contrary, Pompey were alive, he would keep his forces intact for him by all means [at his disposal].

-

Accordingly, having crossed over to Corcyra [modern Corfu], where the fleet was, he offered to give up the command to Cicero, who was of consular rank, while he himself had been only a praetor. But Cicero would not accept the command, and set out for Italy. Then Cato, seeing that [Cnaeus Pompeius, Pompey’s older son] was ... [keen] to punish all those who were about to sail away, starting with Cicero, privately admonished him and calmed him down, thus manifestly saving Cicero from death and procuring immunity for the [others who wanted to return to Italy]”, (‘Life of the Younger Cato’, 55: 2-3).

According to the summary of Livy’s ‘History of Rome’:

-

“Cicero [who was, or claimed to be, ill] had [also] remained in Pompey's camp [at Dyrrhachium], because there was never a man less suited to war than he. Caesar pardoned all the enemies who [surrendered to him]”, (‘Periochae’, 111: 5-6).

We know from a letter that Cicero subsequently wrote to Varro (probably in late June 46 BC) that he (Varro) was also at Pompey’s camp at Dyrrhachium. Cicero now reminisced that, throughout their shared experience:

-

“... your heart was always as heavy as mine. Not only did we foresee the destruction of one of the two armies and its leader, a vast disaster, but we realised that victory in civil war is the worst of all calamities. I dreaded the prospect, even if victory should fall to [the hawks among Pompey’s supporters]. They were making savage threats against the do-nothings [like Cicero and Varro], and your sentiments and my words were alike abhorrent to them. As for the present time, if our friends had gained the mastery [of Rome], they would have used it very immoderately. They were infuriated with us. One might have supposed:

-

✴that we had taken measures for our own safety that we had not advised them to take for theirs; or

-

✴that it was to the advantage of the State that they should go to brute beasts [of Africa - see below] for help rather than ... live in hope.

-

Admittedly, [we are not living in a] very bright hope, but still, it is hope. (‘Letters to Friends’, 181: 3, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 2001, at Vol. II, p. 163).

As we shall see, Caesar subsequently pardoned both Cicero and Varro (in the case of Varro, for the second time), and they were both able to return to Rome.

Cato’s Flight to Africa

Cato’s journeys of 49 - 48 BC, adapted from Wikimedia

According to Plutarch:

-

“Conjecturing, now, that Pompey the Great would make his escape into Egypt or [Cyrenaica], and being eager to join him, Cato put to sea with all his company and sailed away, after first giving those who had no eagerness for the expedition leave to depart and remain behind. After reaching [Cyrenaica], and while sailing along its coast, he fell in with Sextus, the younger son of Pompey, who told him of his father's death in Egypt, [which he had witnessed]. Naturally, everyone was deeply distressed, but now that Pompey was gone, no-one would even listen to any other commander while Cato was at hand. For this reason, ... Cato ... accepted the command, and went along the coast to Cyrene, the people of which received him kindly, although they had closed their gates against Labienus a few days before. There he learned that:

-

✴[Q. Caecilius Metellus] Scipio, the father-in‑law of Pompey, had been well received by Juba the king [of Numidia, to the west of the Roman province)]; and

-

✴[P] Attius Varus, whom Pompey had appointed as governor of [Africa] was with them at the head of an army.

-

Cato therefore set out thither by land in the winter season ... Although the march lasted for 7 consecutive days, Cato led at the head of his force, without using either horse or beast of burden. Moreover, he used to sup in a sitting posture from the day when he learned of the defeat at Pharsalus; yes, this token of sorrow he added to others, and would not lie down except when sleeping. After finishing the winter in [Africa], he led forth his army; and it numbered nearly 10,000 men”, (‘Life of the Younger Cato’, 56: 1-4).

Africa was to become the major place of refuge for those who could or would not return to Italy.

Caesar in Egypt

Caesar’s pursuit of Pompey turned into a naval chase around the eastern Mediterranean. According to Plutarch:

-

“Arriving at Alexandria just after Pompey's death, [Caesar turned away in horror when presented] with the head of Pompey, but he accepted Pompey's signet ring and shed tears over it”, (‘Life of Caesar’, 48: 2).

Caesar now found himself in the midst of a succession crisis, and it seems that his imperious arrival at Alexandria exacerbated tensions:

-

“Upon disembarking, he heard shouts from the soldiers whom [Ptolemy XIII] had left on guard in the city, and saw people converging on him, apparently because he had the fasces ahead of him. The whole crowd was shouting that this amounted to a slight on the king’s majesty. This riot was calmed, but there were frequent disturbances as crowds gathered every day thereafter, and several [Roman] soldiers were killed in every district of the city”, (‘Civil War’, 3: 106: 4-5, translated by Cynthia Damon, referenced below, at p. 345).

For reasons that have never been completely explained, after almost a decade of continuous warfare, Caesar now decided to stop. His own explanation was as follows:

-

“When Caesar understood the situation [in Alexandria], he ordered other legions to be brought to him from Asia, those that he had formed from Pompey’s soldiers. He ... [soon found himself] pinned down by the [prevailing] winds, which are extremely unfavourable for anyone sailing from Alexandria. Meanwhile, thinking that the quarrel between the [contenders for the Egyptian throne, Ptolemy XIII and his sister Cleopatra VII, who had recently been exiled to Syria]:

-

✴pertained to the Roman people, and to himself, since he was consul; and

-

✴was a matter of particular obligation for him, since the alliance [between the Romans and the recently-deceased Ptolemy XII] had been made ... during his earlier consulship;

-

Caesar made his view on the matter clear: Ptolemy and ... Cleopatra should dismiss their armies and debate the points at issue on legal grounds before him, rather than in arms against each other”, (‘Civil War’, 3: 107: 1-2, translated by Cynthia Damon, referenced below, at p. 347).

His decision to stay in Alexandria might also have been influenced by the fact that the Egyptians owed a considerable amount of money to the Romans under the terms of their treaty. This explains why Casear was still at Alexandria at end of his second dictatorship: as we shall see, by this time he had been appointed to his second dictatorship.

Events in Rome in 48 BC

As we have seen, Caesar had already left Rome by the time that he became consul for the second time. His ‘right hand men’ in Rome also left the city at about this time:

-

✴according to Cassius Dio (‘Roman History’, 43: 1: 2), at the end of Lepidus praetorship of 49 BC, Caesar sent him to govern Nearer Spain, where he replaced Pompey’s legate, L. Afranius; and

-

✴as we have seen, Mark Antony accompanied Caesar to the east.

Thus, from the beginning of the new consular year, Caesar’s colleague, Servilius, was in charge at Rome.

P. Servilius Vatia Isauricus

Elizabeth Rawson (referenced below, at p. 431) described Servilius as:

-

“... [the] respected son of the distinguished man [of the same name under whom Caesar] had served in [his] youth, and someone whose adherence [to Caesar’s cause] was perhaps something of a coup.”

One might have expected that Servilius would have chosen Pompey’s cause as the lesser of two evils, particularly because of his apparent closeness to Cato (who was present at Pompey’s camp at this time): this closeness is evidenced by Cicero, who referred to:

-

✴their co-ordinated activity in the Senate in 60 BC in a matter that adversely affected Atticus’ financial interests (see ‘Letters to Atticus’, 21: 10, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. I, p. 135); and

-

✴their joint (albeit unsuccessful) opposition as praetors in 54 BC to the allegedly illegal triumph awarded to C. Pontinus in that year for his victory in Gaul in 61 BC (see ‘Letters to Atticus’, 92: 4, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. II, p. 19).

Furthermore, during his praetorship, Servilius had prosecuted Caesar’s legate, C. Messius, against the wishes of both Caesar and Pompey (both of whom had then ‘requested’ that Cicero should act for the defence - see ‘Letters to Atticus’, 90: 9, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. II, p. 9).

Our surviving sources do not throw much light on the reasons for Servilius’ decision to support Caesar, although it might be relevant that:

-

✴his father had served as one of the consuls of 79 BC, which was the last year of Sulla’s dictatorship; and

-

✴(like Lepidus) he was married to a daughter of Servilia (see, for example, Susan Treggiari, referenced below, at pp. 163-4 and pp. 131-3).

However, all we really say about Caesar’s dealings with Servilius prior to their shared consulship is that, according to Plutarch:

-

“When Caesar came back to Rome [in December 49 BC - see the previous page], Piso, his father-in‑law, urged him to send a deputation to Pompey with proposals for a settlement; but [Servilius], in order to please Caesar, opposed the project.

By this time, of course, Servilius would have been consul-elect.

Political Climate after Caesar’s Departure

Caesar’s choice of Servilius as his consular colleague seems to have been a good one one: Cassius Dio recorded that:

-

“In Rome, as long as the issue between Caesar and Pompey was doubtful and unsettled, everyone in Rome ostensibly favoured Caesar, because of [their fear of the Caesarian troops] in their midst and because of his colleague, Servilius”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 17: 1).

However, no-one was sure that Pompey would not eventually return, and it is likely that most of them refrained from advertising their preferences on the matter. This must have been stressful, since:

-

“... many diverse rumours circulated, often on the same day and even at the same hour, ... [so people] were pleased and distressed, bold and fearful, all within the briefest space of time”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 17: ).

According to Cassius Dio:

-

“When the [result of the] battle of Pharsalus was announced, the [people of Rome] were long incredulous, since Caesar sent no [dispatches to Rome], hesitating to appear to rejoice publicly over ... a victory [over fellow-Romans]: for the same reason, he chose not celebrate a triumph”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 18: 1).

Mark Antony probably brought the first reliable news of the victory with him when he arrived in Italy after the battle (see below). Cassius Dio claimed that many people still doubted that Pompey’s cause was lost, and:

-

“Even when [news arrived that Pompey] had died, they did not believe it ... until they saw his signet ring, which had been sent [from Alexandria]; it had three trophies carved on it, as had that of Sulla”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 18: 3).

The consul Servilius and the urban praetor, C. Trebonius, seem to have been in day-to-day control in Rome for what was left of the consular year of 48 BC,. Their task was complicated by the fact that, as Cassius Dio recorded, M. Caelius Rufus, the praetor peregrinus, stirred up considerable unrest, apparently because he resented the fact that Caesar had chosen Trebonius for what seems to have been the more senior praetorian post:

-

“ Hence, [Caelius] opposed [Trebonius] in everything and would not let him perform any of the duties devolving upon him: he not only refused to consent to [Trebonius] pronouncing judgments according to Caesar's laws, but he also gave notice to that ... he would assist [anyone who was in debt] against their creditor and [anyone who rented a house] that he would release them from payment of the rent. Having gained a considerable following in this way, he attacked Trebonius with their aid and would have killed him, had he not managed to change his dress and escape in the crowd. After this failure, Caelius privately issued a law in which he granted everybody the use of houses free of rent and annulled all debts. Servilius consequently sent for some soldiers who happened to be going by on the way to Gaul and, after convening the Senate under their protection, he proposed a measure in regard to the situation. No action was taken, since the tribunes prevented it, but the sense of the meeting was recorded and Servilius then ordered the court officers to take down the offending tablets. When Caelius drove these men away and even involved [Servilius] himself in a tumult, [the Senate] convened again, still protected by the soldiers, and entrusted to Servilius [special powers that allowed him to suspend Caelius from office] ...”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 22-23).

Caelius then headed for Campania, where T. Annius Milo (who had been exiled from Rome in 52 BC and had now returned without Caesar’s permission) was stirring up a revolt. However, when he:

-

“... reached Campania, and found that Milo, after a defeat near Capua, had taken refuge on Mount Tifata, [he] gave up his plan of going farther, the tribune was alarmed and wished to bring him back home. Servilius ... declared war upon Milo in the Senate and gave orders that Caelius should remain in the suburbs ... [Alarmed], Caelius made his escape and hastened to Milo, ... [only to discover that he] had perished in Apulia. Caelius, therefore, went to Bruttium, ... [where] those who favoured Caesar banded together and killed him”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 25).

According to Caesar (‘Civil War’, 3: 22: 3) Milo had been killed by yet another praetor, Q. Pedius, who was in command of a legion. Nothing in our surviving sources suggests that Mark Antony played any part in these events.

Reaction at Rome to News of Pompey’s Death (October 48 BC)

Cassius Dio recorded that it was only at this point that the Senate conferred a number of unprecedented honours on Caesar:

-

“They:

-

✴granted him permission to do whatever he wished to those who had favoured Pompey's cause ... ;

-

✴appointed him as the arbiter of war and peace ... , without the obligation [even to consult] the people or the Senate on the subject; ...

-

✴[awarded him] the privilege of holding:

-

•the consulship for five consecutive years [although, as we shall see, he did not trouble to assume the consulship of 47 BC];

-

•the dictatorship, not for six months, but for an entire year [see below]; and ... the tribunician power, practically for life; ...

-

✴[gave him control of] all the [annual elections of magistrates] except those of the plebs ... and, for this reason, [these elections] were delayed until after his arrival and were held toward the close of the year [sic: as we shall see, Caesar did not return to Rome until October 47 BC];

-

✴voted that he should appoint praetorian governors to provinces without the casting of lots, (although they pretended that they would first assign the provinces that would be given to the consuls); ... and

-

✴decreed that he should hold a triumph for the war against Juba and the Romans who fought with him, just as if had been the victor, even though this war had yet to be fought [see below]”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 20).

I have removed a great deal of polemic from this long passage in order to isolate its allegedly factual content. As Cassius Dio pointed out (ad nauseam), these ‘honours’ essentially legitimised powers that Caesar already enjoyed and reflected the terror with which many senators awaited Caesar’s return to Rome.

Caesar’s 2nd Dictatorship (Oct. 48 - Sept. 47 BC)

As we have seen, Cassius Dio recorded that, after the news of Caesar’s victory at Pharsalus and Pompey’s subsequent death reached Rome, the Senate granted honours to Caesar, in his absence, among which were:

-

“... the privilege of being consul for five consecutive years and of being chosen dictator, not for six months, but for an entire year, and he assumed the tribunician authority practically for life”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 20: 3).

Plutarch similarly commented that Caesar had reached Rome his victory at Zela (2nd August 47 BC - see below):

-

“...at the close of the year for which he had a second time been chosen dictator, though that office had never before been for a whole year”, (‘Life of Caesar’, 51: 1).

It is usually assumed that Caesar’s second dictatorship ran from October 48 BC to September 47 BC (see, for example, Robert Broughton, referenced below, at p. 272 and note 1, pp. 284-5 and Andrew Drummond, referenced below, at p. 564).

More specifically, she argued that the iconography of RRC 456/1, which included Caesar’s new title and a number of ritual objects:

-

“... paired political and religious ritual guaranteeing the welfare of Rome in the first coin Caesar issued after defeating Pompey and the forces of the senatorial government. [Caesar’s assassins] would re-use this coin design in a way that makes very clear that [they] understood (and imagined a Roman audience to understand) the symbols not as short-hand for personal tenure of priesthood but as claims of religious piety and authority.”

The mint from which this coin was issued is uncertain: as we shall see, Caesar remained away from Rome for most, if not all, of his second dictatorship, which has led most scholars (including Michael Crawford, referenced below, at p. 471 and Roberta Stewart, referenced below, at p. 114) to assume that it was minted in the east. However, it seems to me that its political message was intended for the audience in Rome.

According to Plutarch, when Caesar:

-

“... had been proclaimed dictator [in absentia], he himself pursued Pompey [to Alexandria]: he chose Antony as his master of horse and sent him to Rome”, (‘Life of Mark Antony’, 8: 1-2).

Cassius Dio recorded that:

-

“Caesar entered upon [his second] dictatorship at once, although he was outside of Italy, and chose [Mark] Antony as his master of horse, although he had not yet been praetor. The consuls, [Caesar himself and Servilius] also proposed the latter's name, although the augurs very strongly opposed him, declaring that no-one could be master of horse for more than six months. But, by acting in this way, they brought upon themselves a great deal of ridicule because, after having decided that the dictator himself should be chosen for a year, contrary to all precedent, they were now splitting hairs about the master of the horse”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 21: 1-2).

Taking these two accounts together, we can reasonably assume that Mark Antony brought instructions from Caesar that Servilius should appoint him as dictator, with Mark Antony as his master of horse. This dictatorship appeared in the Augustan fasti Capitolini under 47 BC: it can be translated and completed as follows:

-

Dictator C. Julius C.f. C.n. Caesar II , [magister equitum:] M. Antonius M.f. M. n. - [in order to manage public affairs - see below]

(Mark Antony’s name seems to have been erased and subsequently restored)

Unlike Caesar’s first dictatorship (which, as we have seen, had been specifically connected with the election for the consuls of 48 BC), his second (like the others that followed it) was almost certainly described as rei gerundae caussa ‘for the purpose of conducting affairs’: as Mark Wilson (referenced below, at p. 24) observed, this had traditionally been:

-

“... the catch-all caussa usable for varying circumstances (anything from defending Rome from invaders and attacking distant enemies to judicial probes and domestic unrest) ...”

Elizabeth Rawson (referenced below, at p. 458) observed that Caesar had made a conscious effort to observe the constitutional niceties up to this point, albeit that some irregularities had inevitably been necessary, but argued (at p. 459) that:

-

“The real rot set in after Pharsalus, when Caesar was elected dictator for a year ...”

As noted above, both Cassius Dio and Plutarch assumed that the unprecedented thing about this specified term was that it was longer than the allegedly traditional six months. However, as Mark Wilson (referenced below, at p. 49) pointed out, the idea that the dictatorship had traditionally lasted for six months:

-

“... betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of an office that was, in fact, bound to a mandate.”

In other words, during the centuries in which the dictatorship was a relatively common occurrence, a dictator appointed rei gerundae caussa would:

-

✴serve alongside the consuls who appointed him and take the lead on the particular task for which he was appointed; and

-

✴resign when he had completed his allotted task.

What was unprecedented about this dictatorship was that:

-

✴Caesar still had three months left as consul when he was appointed (probably by his consular colleague); and

-

✴his appointment was not associated with a specific mandate but simply terminated after a year.

Events of 47 BC

Aureus issued by Caesar: 47 BC (RRC 456/1)

Obverse: CAESAR DICT: Axe and culullus

Reverse: ITER: Jug and lituus, laurel-wreath border

Mint uncertain

The coin illustrated above sheds some light on how Caesar wished to portray himself as dictator for the second time. It certainly broke new ground in respect of its iconography: as Roberta Stewart (referenced below, at p. 114) pointed out, it;

-

“... contains only religious symbols. The design is new: obverse (axe and two-handled cup) and reverse (jug and lituus) combine to make a continuous frieze of ritual implements. The division of the legend (CAESAR DICT on the obverse and ITER on the reverse) emphasises the unity of the doubled round fields.”

Robert Broughton (referenced below, at p. 293) assumed that the presence of the lituus indicated that Caesar became an augur during his second dictatorship, although the earliest direct evidence comes in a letter (‘Letters to Friends’, 211, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below , 2001, at Vol. II, p. 273) that Cicero wrote to his fellow-augur, P. Servilius Isauricus, in October 46 BC in which he referred to Caesar as their colleague.

Roberta Stewart (referenced below, at p. 114) argued that there is no reason to believe that Caesar was an augur at the time of his second dictatorship, and more generally that this coin and RRC 443/1 (illustrated at the top of the page) belonged to a group of Caesar’s coins that employed ritual object that were not chosen to reflect Caesar’s personal tenure of specific priesthoods. Instead (see, for example, p. 119), they:

-

“... featured ritual friezes that selectively invoked sacrificial ritual and the traditional rituals that framed political authority.”

Events in Rome (January - September 47 BC)

As Geoffrey Sumner (referenced below, at p. 259) pointed out, after the news of Pompey’s death on 28th September 48 BC reached Rome:

-

“Caesar was granted the right:

-

✴to hold the consulship for five successive years,

-

✴to be dictator for a whole year ... ; and

-

✴to conduct all elections (except those in the plebeian assembly).

-

The elections for magistrates of 47 BC (other than those of the plebs) were, as a result, held up until Caesar's return to Rome in autumn of 47 BC. These magistrates enjoyed office for a mere three months or so.”

Cassius Dio recorded that, after the end of Servilius’ term as consul, there was:

-

“... neither consul nor praetor and, while [Mark] Antony ... convened the Senate [in his capacity as Caesar’s master of horse, and] furnished some semblance of the Republic, yet the [fact that he was armed and accompanied by a] throng of soldiers and, in particular, [the manner in which he conducted himself] indicated the existence of a monarchy. In fact many robberies, outrages, and murders took place. ... [Furthermore, many in Rome] suspected Caesar of intending far more and greater deeds of violence. For, if the master of the horse never laid aside his sword even at the festivals, who would not have been suspicious of the dictator himself?”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 27: 2-3).

As Elizabeth Rawson (referenced below, at p. 459) observed, Mark Antony’s:

-

“... anomalous position was symbolised by the fact that, in Rome, he wore the civilian toga, [but carried] a sword.”

His role as Caesar’s representative is clear from a letter that Cicero (who had returned from the Pompeian camp at Pharsalus to Brundisium and was waiting for Caesar’s permission to return to Rome) wrote to Atticus of 17th December 48 BC: he complained that:

-

“... I have almost been ordered out of Italy! [Mark] Antony has sent me a copy of a letter from Caesar to himself, in which Caesar says that:

-

✴he has heard that [the Pompeian pro praetor, M. Porcius Cato] and L. [Caecilius] Metellus, [who, as plebeian tribune, had tried to deny Caesar access to the treasury in 49 BC] have returned to Italy, intending to live openly in Rome, but he does not approve of this in view of the risk of the resulting disturbances; and

-

✴all persons are barred from Italy except those whose cases he has personally reviewed.

-

He [Caesar] expressed himself pretty strongly on [the last] point. So, Antony wrote, asking me to excuse him, since he had no choice but to obey the letter”, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 218, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. III, pp. 203-5).

Fortunately for Cicero, he was able to point out that Caesar had instructed P. Cornelius Dolabella (Cicero’s son-in-law, who had fought under Caesar at Pharsalus and who served as a plebeian tribune in 47 BC - see below) to invite Cicero to return. As we shall see, he nevertheless found it expedient to remain at Brundisium for most of 47 BC.

Mark Antony’s position was undermined by dissent among the new plebeian tribunes: C. Asinius Pollio; P. Cornelius Dolabella; and L. Trebullius. According to Plutarch:

-

“Dolabella, ... a newcomer in politics who aimed at a new order of things, introduced a law for the abolition of debts, and tried to persuade [Mark] Antony, who was his friend and always sought to please the multitude, to [support this] measure. But Asinius and Trebellius advised [Mark] Antony to the contrary and, as chance would have it, a [current rumour alleged that Dolabella was conducting an affair with Mark Antony’s wife]. Antony ... [therefore] made common cause with Asinius and Trebellius ... The Senate [duly decreed] that arms must be employed against Dolabella: [Mark Antony then] ... joined battle [with Dolabella], killed some of his men and lost some of his own”, (‘Life of Antony’, 9: 1-2).

He also had to deal with discontent among Caesar’s veterans. As Stefan Chrissanthos (referenced below, at p. 69) pointed out, Caesar had sent nine veteran Gallic legions to Italy after Pharsalus, and Mark Antony had billeted them in Campania to await Caesar's return. However, Cassius Dio recorded that, while Mark Antony was coping with the unrest at Rome described above, he:

-

“... learned that the legions which Caesar after the battle had sent ahead into Italy, with the intention of following them later, were engaged in questionable proceedings. Fearing that they might begin some rebellion, [Mark Antony] turned over the charge of the City to Lucius Caesar [consul of 64 BC, Julius Caesar’s cousin and Mark Antony’s uncle], appointing him Urban Prefect, an office never before conferred by a master of the horse, and then set out himself to join the soldiers”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 30: 1).

The build-up of this tension can be seen in a number of letters that Cicero wrote to Atticus:

-

✴on 19th January, he mentioned:

-

“... the alienation of public feeling in Italy, the diminished vigour and loyalty of the troops, the desperate state of affairs in Rome”, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 221, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. III, p. 217).

-

✴on 3rd June, he referred to the knocks that Caesar had suffered:

-

“... in Asia [at Nicopolis - see below], ... in Illyria [where his legate A. Gabunus had been killed], ... in the Cassius affair [when Cassius’ troops in Spain had mutinied], ... in Alexandria itself [see below], in Rome, in Italy”, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 227, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. III, p. 235).

-

Stefan Chrissanthos (referenced below, at p. 72 and notes 161-2) argued that, in this letter, the knock in Italy related to an outright mutiny of the veteran legions, and that this was the occasion on which he had been forced to leave Rome in the hands of L. Julius Caesar (see above), and that Mark Antony lacked the resources needed to meet the soldiers’ demands.

According to [Caesar], on his arrival in Syria in late July (see below) Caesar himself:

-

“... learned from those who had joined him there from Rome, as well as from information contained in despatches from the city, that there was much that was bad and unprofitable in the administration at Rome, and that no department of the government was being really efficiently conducted, for rivalries among the tribunes, it was said, were producing dangerous rifts, and the flattering indulgence shown to their troops by the military tribunes and legionary commanders [in Campania] was giving rise to many practices opposed to military custom and usage which tended to undermine strict discipline”, (‘Alexandrian War’, 65: 1, translated by A. G. Way, referenced below, at p. 115).

As we shall see, the situation in Campania was still unresolved when Caesar finally returned to Italy in late September 47 BC.

Caesar in Egypt (January 48 - July 47 BC)

Unfortunately, Caesar had over-estimated the strength of his position, and soon found himself besieged by Achillas. At some time during this siege, Cleopatra apparently returned to Alexandria and succeeded in having herself smuggled into Caesar’s presence. The arrival in early 47 BC of reinforcements and supplies sent by Cn. Domitius Calvinus (whom Caesar had sent to govern Asia after Pharsalus - see below) and by Mithridates of Pergamum (a Roman ally) proved decisive in ending the siege: Ptolemy’s army was routed and he drowned as he tried to escape along the Nile. According to [Caesar]:

-

“This signal victory ... filled Caesar with such confidence that he hastened with his cavalry to Alexandria ... and entered it triumphantly ... On his arrival, he reaped the well-earned fruits of valour and magnanimity; for the entire population of the city threw down their arms and abandoned their fortifications. They assumed the garb in which suppliants traditionally placated tyrants with earnest prayers, and brought forth all the sacred emblems by the sanctity of which they had been wont to [soften ?] the embittered and wrathful hearts of their kings. In this way, they hastened to meet Caesar on his arrival and surrendered themselves to him. Caesar took them formally under his protection and consoled them. Then, passing through the enemy fortifications, he came to his own quarter of the city amid loud cheers of congratulation from his own troops ...”, (‘Alexandrian War’, 32, translated by A. G. Way, referenced below, at pp. 61-3).

The fasti Maffeiani recorded a later annual festival celebrating Caesar’s victory at Alexandria on 27th March, and this victory resulted in the second of four triumphs that Caesar celebrated in September 46 BC (see below).

Caesar now settled the matter of the succession:

-

“Having made himself master of Egypt and Alexandria, Caesar appointed those whom [Ptolemy XII] had named [as his successors] in his will with an earnest appeal to the Roman people that they should not be altered. [However, since Ptolemy XIII] was now no more, Caesar assigned the kingdom to the younger [son] and to Cleopatra ...”, (‘Alexandrian War’, 33: 1, translated by A. G. Way, referenced below, at p. 63).

He then seems to have embarked on a well-earned holiday: as late as 14th June 47 BC, Cicero wrote to Atticus from Brundisium (where he was anxiously awaiting Caesar’s return), complaining that:

-

“... there is no news here of [Caesar] having left Alexandria, and it is agreed that no-one at all has left there since 15th of March, and that [Caesar himself] he has sent no dispatches since 13th of December [48 BC]”, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 229, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. III, pp. 239-41).

He wrote again on 5th July to tell Atticus that:

-

“There is an unauthoritative report that Caesar has left Alexandria. It arose from a letter [written by] Sulpicius [presumably P. Sulpicius Rufus, pr. 48 BC], which all subsequent advices have gone to confirm. As its truth or falsity does not make any personal difference to me, I cannot say which I should prefer”, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 231, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. III, p. 243).

Allowing for the time taken for news to travel from Alexandria to Rome, it seems that Caesar had been incommunicado for six months or more.

Events in Spain 48 -47 BC

As we have seen, Caesar had defeated the Pompeian governors of Spain (M. Petreius, L. Afranius and M. Terentius Varro) in 49 BC and, had then left Q. Cassius Longinus in command of his legions there. According to the now-unknown author of the “Alexandrian War’, whom I have designated [Caesar], Cassius held the post of pro praetor in Hispania Ulterior:

-

“... during the period when Caesar was besieging Pompey at Dyrrachium, achieving success at ... Pharsalus and engaged at Alexandria [i.e., in the period July 48 - June 47 BC]”, (‘Alexandrian War’, 48, translated by A. G. Way, referenced below, at p. 89).

According to the surviving summary of the now-lost Book 111 of Livy’s ‘History of Rome’, in 48 BC:

-

“Because of the avarice and cruelty of pro praetor Q. Cassius, the inhabitants of Cordoba in Hispania, together with the two legions of Varro, abandoned the cause of Caesar”, (‘Periochae’, 111: 4).

[Caesar] gave a relatively detailed account of the events that followed:

-

✴As a result of Cassius’ abusive behaviour, a group of local people attempted to assassinate him at Cordoba. The plot failed and, shortly after Cassius had executed the would-be assassins, he learned of Caesar’s victory at Pharsalus (paragraphs 49-56).

-

✴When some of the legions at Cordoba mutinied, Cassius sent his quaestor, M. Marcellus to deal with the situation. The city council at Cordoba joined the revolt, together with the Roman garrison in the city:

-

“Marcellus, either of his own free will or under compulsion (reports varied on this point) was hand in glove with the [revolt at] Corduba”, (‘Alexandrian War’, 57, translated by A. G. Way, referenced below, at p. 103).

-

✴Cassius and Marcellus established their respective camps on either side of the river Baetis outside Cordoba. Cassius:

-

“... sent despatches to ...M. Lepidus, the pro-consul in Hispania Citerior, urging [him] to come as soon as possible to the aid of himself and the province, in the interest of Caesar”, (‘Alexandrian War’, 59, translated by A. G. Way, referenced below, at pp. 105-7).

-

Cassius then moved his camp to Ulia, a short distance to the south, and Marcellus followed him.

-

✴ Lepidus arrived at Ulia with 35 legionary cohorts and a large number of cavalry:

-

“... his object being to resolve, quite impartially, the dispute between Cassius and Marcellus”,(‘Alexandrian War’, 62-63, translated by A. G. Way, referenced below, at p. 111).

-

✴When negotiations broke down, Lepidus and Marcellus established a joint camp at Corduba and Cassius moved to Carmo, a short distance to the west:

-

“At about the same time, C. Trebonius arrived to govern [Hispania Ulterior] as pro-consul. When Cassius learned of his coming, he ... hastened to Malaca, where he embarked, ... [although] it was winter... His ship sank in the mouth of the [Ebro] and he perished”,(‘Alexandrian War’, 64, translated by A. G. Way, referenced below, at p. 113).

The likelihood is that, when Cassius set out on his ill-fated voyage, he had been hoping to reach Caesar in order to give his own account of recent events.

At this point, we should consider how Lepidus and Trebonius had become involved in these events in Hispania Ulterior:

-

✴As we have seen, when Caesar had left Rome in October 49 BC, he had left Lepidus in charge of the City as urban praetor. According to Cassius Dio,

-

“... immediately after [Lepidus’] praetorship, [Caesar sent him] into Hispania Citerior and, upon his return, honoured him with a triumph, although he had conquered no foes and fought no battles, the pretext being that he had been present during the conflict between Cassius and Marcellus”, (‘Roman History’, 43: 1: 1-3).

-

In other words, Lepidus had governed Hispania Citeriore for the whole of 48 and 47 BC before returning to Rome, where Caesar allowed him to triumph. The records in the fasti Triumphales for the period 53-46 BC no longer survive but Lepidus’ triumph of 43 BC (once more in Spain) is recorded in the fasti as his second. There is no reason to doubt Cassius Dio’s assertion (above) that the triumph had been justified by the part that Lepidus had played in sorting out the conflict between Cassius and Marcellus. Richard Weigel (referenced below, at p. 31) suggested that Caesar had awarded it in late 47 BC in order to boost Lepidus’ prestige prior to his inauguration in the following year as Caesar’s consular colleague (see below).

-

✴We have also seen that Trebonius had succeeded Lepidus as urban praetor, and that he had been dealing with the uprising of M. Caelius Rufus in October - December 48. In a letter that Cicero wrote to Trebonius in late 46 BC, he referred back to Trebonius’:

-

“... intention to visit me at Brundisium, had you not suddenly been ordered to Spain”, (‘Letters to Friends’, 207, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 2001, at Vol. II, p. 259).

-

Cicero had arrived in Brundisium in October 48 BC. and Caesar was incommunicado from 13th December 48 BC: we might reasonably assume thatCaesar had ordered Trebonius sudden departure for Spain during this period.

Since:

-

✴Lepidus was awarded a triumph when he returned to Rome in late 47 BC; and

-

✴Trebonius’ governorship of Hispania Ulterior was extended into 46 BC;

we might reasonably assume that the situation on Spain had remained reasonably stable throughout 47 BC.

Events in the Eastern Provinces (December 48 - August 47 BC)

Battle of Nicopolis (December 48 BC)

In 48 BC, King Pharnaces of Pontus (in what is now northern Turkey) had exploited the Romans’ internal distractions by attacking the neighbouring kingdoms of Armenia and Cappadocia. Both of their rulers, who were allied to Rome, sought help from Cn. Domitius Calvinus, whom Caesar had appointed as governor of Asia Minor. However (as we have seen) Calvinus had sent most of his army to aid Caesar at Alexandria, so he was forced to rely to a considerable extent on the armies of his allies, and Pharnaces duly defeated him at Nicopolis in December 48 BC. According to Aulus Hirtius:

-

“After sustaining this defeat, ... [Calvinus] collected the remnants of his scattered army and withdrew by a safe routes through Cappadocia into Asia”, (‘Alexandrian War’, 65: 1 - 66: 1, translated by A. G. Way, referenced below, at pp. 115-7).

Thus, as Gareth Sampson (referenced below, at p. 89) observed:

-

“With the onset of winter, Pharnaces found himself in the same position as his father, Mithridates VI: he had defeated the Romans, ejected them from Asia Minor and recreated the Pontic Empire.”

Caesar in Syria (July 47 BC)

Caesar did not immediately respond to Pharnaces’ victory. However, according to Plutarch:

-

“... leaving Cleopatra on the throne of Egypt (a little later she had a son by him whom the Alexandrians called Caesarion), he set out for Syria [in the summer of 47 BC]”, (‘Life of Caesar’, 49: 10).

According to Aulus Hirtius:

-

“On his arrival in Syria ... , Caesar learned from those who had joined him there from Rome, as well as from information contained in despatches from the City, that there was much that was bad and unprofitable in the administration at Rome [see below]. ... He saw that all this urgently demanded his presence: yet, for all that, he thought it more important to leave all the provinces and districts he visited [in good order] .... He was confident he would speedily achieve this in Syria, Cilicia and Asia, as these provinces had no war afflicting them: ... He spent some time in practically all the more important states of Syria ... [and, when all was in order, he] posted Sextus Caesar, his friend and kinsman, to command the legions and govern Syria ...”, (‘Alexandrian War’, 65: 1 - 66: 1, translated by A. G. Way, referenced below, at pp. 115-7).

Hirtius then noted that Caesar rapidly dealt with the affairs of Cilicia and Asia.

Battle of Zela (2nd August 47 BC)

Caesar now marched north into Pontus, and finally engaged with Pharnaces at Zela (where Pharnaces’ father, Mithridates VI, had defeated the Romans some 20 years earlier). However, the result on this occasion was a rapid and comprehensive Roman victory: as Plutarch famously recorded, Caesar:

-

“... drove [Pharnaces] ... out of Pontus and annihilated his army. In announcing the swiftness and fierceness of this battle to C. Matius, one of his friends at Rome, Caesar wrote only three words: [they were rendered in Latin as]: ‘Veni, vidi, vici’ (I came, I saw, I conquered)”, (‘Life of Caesar’, 49: 10 - 50: 3).

A number of early imperial calendars (including the fasti Fratrum Arvalium, the fasti Maffeiani and the fasti Antiates Ministrorum) recorded a later annual festival celebrating Caesar’s victory at Zela on 2nd August (see, for example, Gian-Luca Gregori et al., referenced below, at p. 141), and this victory resulted in the third of four triumphs that Caesar celebrated in September 46 BC ( see below).

According to Aulus Hirtius:

-

“Having thus recovered Pontus and made a present to his troops of all the royal plunder, [Caesar] set out on the following day ..., leaving two legions in Pontus with [M.] Caelius Vinicianus.”, (‘Alexandrian War’, 77: 1-2, translated by A. G. Way, referenced below, at pp. 133-5).

Hirtius then recorded Caesar’s rapid march through Gallatia and Bithynia into Asia. He conferred most the territory that had belonged to Pharnaces on his ally Mithridates of Pergamum (see above). Gareth Sampson (referenced below, at p. 94) observed that:

-

“With his overwhelming victory over Pharnaces, Caesar restored full Roman control of the east under the remaining Roman legions and Rome’s client kings, allowing him to return west to pursue the civil war against [the remaining] Pompeian forces. In Syria itself, Caesar left one legion under the command of his cousin, Sex. Julius Caesar. The whole region, and Parthia especially, had been given a clear indication that, despite the on-going civil war, Rome’s military might ... was as destructive as ever, as was its resolve to hold onto control of the region: ... though [Caesar’s immediate] attention moved to the west (first to Africa and then to Spain), the east [remained] very much in [his] mind.”

Caesar’s Brief Return to Italy (September 47 BC)

According to Stefan Chrissanthos (referenced below, at p. 72), after his victory at Zela, Caesar:

-

“... was in a great hurry to engage the Pompeians [who had mustered] in Africa, and was [therefore] not planning a prolonged stay in Italy ... Discharge and rewards [for his long-suffering legions] would have to wait until the new threat [from Africa] was ended. He had received reports about the disturbances [among the legions stationed] in Campania while he was in Syria, on or before I8 July [see above]. Despite these reports, [he] apparently did not believe the situation was serious ... He [therefore] sent legates from the East with orders to move the veteran legions from Campania to Sicily, where he would join them and sail with them to Africa. Apparently these legates had no special instructions or monetary bonuses to deal with recalcitrant armies, nor any orders for discharge. Three of the men that Caesar sent from the East are known: M. Gallius; P. Cornelius Sulla; and M. Valerius Messalla.”

The dates at which the legates arrived can be found from three letters from Cicero to Atticus from Brundisium:

-

✴15th August:

-

“M. Gallius ... has come to take the legions over to Sicily. Caesar [himself] is supposed to be going there direct from Patrae [on the northwest coast of Greece]”, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 235: 2, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. III, p. 255).

-

✴17th August:

-

“The 12th legion, the first approached by [P. Cornelius] Sulla, is said to have driven [him] off with volleys of stones. It’s thought that none of [the veteran legions in Campania will obey the order to] move”, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 236: 2, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. III, p. 257).

-

✴1st September:

-

“Sulla, I believe, will be here tomorrow with [M. Valerius] Messalla. They are hurrying off to Caesar [at Tarentum - see below], having been sent packing by the troops, who refuse to go anywhere until they get their pay. So, contrary to expectation, Caesar will be coming here [to Brundisium, instead of making for Sicily]; though the way he is travelling, stopping a number of days at every town (?), it won’t be soon”, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 237: 2, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. III, p. 259).

Meanwhile, according to Plutarch:

-

“... word was brought [to Cicero] that Caesar had landed at Tarentum and was coming round by land from there to Brundisium”, (‘Life of Cicero’, 39: 4).

On 12th August 47 BC, Cicero wrote from Brundisium to Terentia, his wife to inform her that:

-

“I have at last received a letter from Caesar, quite a handsome one. He is said to be arriving in person sooner than was expected”, (‘Letters to Friends’, 171, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 2001, at Vol. II, p. 137).

Caesar followed up his letter by meeting Cicero during his journey to Rome.: according to Plutarch:

-

“Cicero hastened to meet him, being not altogether despondent, but feeling shame to test in the presence of many witnesses the temper of a man who was an enemy and victorious. However, there was no need that he should do or say anything unworthy of himself since, when Caesar saw him approaching far ahead of the rest, he got down and embraced him, and travelled on for many furlongs, conversing with [Cicero] alone”, (‘Life of Cicero’, 39: 4-5).

The meeting clearly went well, since Cicero wrote again to Terentia on 1st October 47 BC to inform her (somewhat peremptorily) that he had decided to move from Brundisium to his villa in Tusculum ((‘Letters to Friends’, 173, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 2001, at Vol. II, p. 139).

Once Caesar reached Rome, he concentrated primarily on raising much-needed revenue (see, for example, Cassius Dio ‘Roman History’, 42: 50 - 51). Dio also recorded that:

-

“The legions ... caused him considerable trouble, since they had expected to receive a great deal and, when they found their rewards to be below their expectations, ... they made a disturbance. Most of them were in Campania, being destined to sail on ahead to Africa: these nearly killed [C. Sallustius Crispus], who had been appointed praetor in order to recover his senatorial rank; and when, after escaping them, he set out for Rome to inform Caesar of what was going on, many followed him, sparing no one on their way, but killing, among others whom they met, two senators”, ‘Roman History’, 42: 52: 1-2)

Stefan Chrissanthos (referenced below, at p. 75) argued that:

-

“... the mutiny of 47 BC was far more serious than has generally been recognised, and [it] was not quelled with the ease [that is] often assumed. While the civil war still raged, nine of Caesar's ten veteran legions mutinied. What mattered most to Caesar was to get these legions, his best troops, to fight in Africa. This did not happen. Instead, he took only five veteran legions, supplemented by five legions of recruits. He discharged the four remaining legions, and rewarded them with money and land.”

Mark Antony and the Suffect Consuls of 47 BC

Since Caesar’s year as second dictatorship ended at this point, so too did Mark Antony’s term as master of horse. Caesar therefore had to make arrangements for the governance of Rome and Italy before he could safely leave for Africa. Cassius Dio recorded that:

-

“... in the year in which [Caesar] had really ruled alone as dictator for the second time, ... [his legates, Q. Fufius] Calenus and [P.] Vatinius, were appointed near the close of the year and said to be the consuls”, ‘Roman History’, 42: 55: 42).

The Augustan fasti Capitolini recorded that, in 47 BC:

-

✴Dictator: C. Julius C.f. C.n. Caesar II , [master of horse]:M. Antonius M.f. M. n. - [in order to manage public affairs];

-

✴Consuls in the same year: Q. Fufius Q.f. C.n. Calenus; P. Vatinius [P.f.]

Robert Broughton (referenced below, at p. 286) suggested that Calenus and Vatinus were ‘elected’ after Caesar's during Caesar’s brief visit to Rome. As we shall see on the following page, Mark Antony now disappears from our surviving sources until September 45 BC.

Read more:

Sampson G. “Rome and Parthia: Empires at War: Ventidius, Antony and the Second Romano-Parthian War, 40–20 BC”, (2020) Yorkshire and Philadelphia

Gregori G-L. and Almagno G. (authors) and T. Spinelli (editor and translator), “Roman Calendars: Imperial Birthdays, Victories and Triumphs”, (2019) Mauritius

Luibimova O., “The Meaning of Legend LII on Civil War Coinage of Caesar (RRC 452)”, Panel 3 from the seminar (2019) on “The Roman Civil Wars of 49–30 BC” at the British School at Rome

Treggiari S., “Servilia and her Family”, (2019) Oxford

Stewart R., “Seeing Caesar’s Symbols: Religious Implements on the Coins of Julius Caesar and his Successors”, in:

Elkins N. T. et al. (editors), “Concordia Disciplinarum : Essays on Ancient Coinage, History and Archaeology in Honor of William E. Metcalf”, (2018) New York, at pp. 107-2121

Ramsey, J. T. and Raaflaub, K. A., “Chronological Tables for Caesar's Wars (58–45 BC)” , Histos, 11 (2017) 162–215

Wilson M. “The Needed Man: The Evolution, Abandonment and Resurrection of the Roman Dictatorship”, (2017) thesis of the City University of New York

Damon C. (translator), “Caesar: Civil War’, (2016) Cambridge, MA

Kopij K., “The Context and Dating of the Pompey's Aureus (RRC 402)”, Numismatica e Antichità Classiche, 45 (2016) 109–28

Shackleton Bailey D. R. (translator), “Cicero: Philippics , 1-6 (Vol. I) and Books 7-14 (Vol. II)”, (2010) Cambridge, MA

Carter J. (translator), “Caesar: The Civil War’, (2008) Oxford and New York

Shackleton Bailey D. R. (translator), “Cicero: Letters to Friends, Vol. I: Letters 1-113”, (2001) Cambridge, MA

Shackleton Bailey D. R. (translator), “Cicero: Letters to Atticus, Vol. I- IV”, (1999) Cambridge MA

Crissanthos S. G., “Caesar and the Mutiny of 47 BC”, Journal of Roman Studies, 91 (2001) 63-75

Sear D., “The History and Coinage of the Roman Imperators (49-27 BC)”, (1998) London

Rawson E., “Caesar: Civil War and Dictatorship”, (Chapter 11) and “Aftermath of the Ides of March”, (Chapter 12), in:

Crooke J. A. et al., (editors), “Cambridge Ancient History, Volume IX: Last Age of the Roman Republic (146-43 BC”, (1992) Cambridge, at pp. 424-90

Weigel R., “Lepidus: The Tarnished Triumvir”, (1992) London

Drummond A., “The Dictator Years”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 27:4 (1978), 550-72

Fantham E., “Cicero, Varro, and M. Claudius Marcellus”, Phoenix, 31: 3 (1977) 208-13

Crawford M., “Roman Republican Coinage”, (1974) Cambridge

Sumner G. V., “The Lex Annalis under Caesar”, Phoenix, 25:3 (1971) 246-71

Way A. G. (translator), “Caesar.: Alexandrian War; African War; Spanish War”, (1955) Cambridge MA

Broughton T. R. S., “The Magistrates of the Roman Republic. Vol. II : 99 BC - 31 BC”, (1952) New York

Falconer W. A. (translator), “Cicero; On Old Age; On Friendship; On Divination”, (1923) Cambridge MA

Return to Roman History (1st Century BC)

Home