Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Clavus Annalis (Annual Nail)

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Clavus Annalis (Annual Nail)

Archaic Rite of the ‘Clavus Annalis’

Livy recorded that, in 363 BC, in circumstances described below:

“The Senate ... decreed the appointment of a dictator clavi figendi causa (dictator for fixing the nails) and nominated L. Manlius Imperiosus for that purpose”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 4-5).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 73) argued that the passage that followed constituted a discrete digression on the archaic rite of clavi fixatio (the fixing of the nails):

✴The digression began with Livy’s citation of:

“... an ancient law, written in archaic words and letters, [which stipulated] that:

qui praetor maximus sit idibus Septembribus clavum pangat

(He who is praetor maximus on the Ides [15th] September shall hammer in a nail).

This notice was fixed on the right side of the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, in the part where the chapel of Minerva is”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 5; see also the translation by Edward Bispham and Timothy Cornell, in T, C. Cornell (editor), referenced below, in Vol. I, p. 183 for this and the translations that follow).

✴Livy explained that:

“This nail is said to have been a record of the number of years (written records being scarce in those days), and the reason why the law was placed in the chapel of Minerva was that numbers are an invention of hers”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 5-6).

✴Livy then referred to an apparent Etruscan precedent (discussed below) for the archaic ritual of fixing the nail:

“Cincius, diligens talium monumentorum auctor (a careful student of monumenta of this kind), asserts that, at Volsinii [Etruscan Velzna, modern Orvieto], nails were fixed in the temple of Nortia, an Etruscan goddess, to indicate the number of the years”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 7).

✴Finally, Livy described how the Romans of his day imagined that the original archaic rite had evolved over the period 509 - 363 BC:

“The consul M. Horatius [Pulvillus] †established the law and dedicated the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus† in the year following the expulsion of the kings [conventionally in 509 BC]. The solemn fixing of the nail handed over from the consuls to the dictators, since their imperium was greater. Although the custom had been given up, the ritual in itself was deemed worthy and for this reason the dictator was named”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 8).

(See Stephen Oakley, referenced below, 1998, at p. 82 for the translation of the obelised passage above and Ross Holloway, referenced below, at p. 112 for the translation of the last two lines.) Both the pre-Julian fasti Antiates Maiores and Plutarch (‘Life of Publicola ’, 14: 3) record that the the dies natalis of the temple fell on the Ides of September.

Oakley (as above) argued that:

“The digression is carefully marked by ring-composition: ... [the reference at line 5 to] L. Manlius Imperiosus ... [is] picked up by [the phrase at ‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 9]: ‘qua de causa creatus L. Manlius’ (This was the reason for L. Manlius’ appointment)”.

L. Cincius

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 73) argued that Cincius, whom Livy cited (at line 7) for the Etruscan precedent of the annual driving of a nail at a temple to mark time, was probably also the source of most of the other information in lines 5-8 and that Livy had:

“... consulted [him] for the particular purpose of composing [this] digression.”

Edward Bispham and Timothy Cornell (in T, C. Cornell (editor), referenced below, in Vol. I, p. 183) argued that Livy’s description of Cincius as diligens talium monumentorum auctor:

“... must point to the antiquarian L. Cincius rather than the historian [L. Cincius Alimentus (the subject of their analysis)]”. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 81) agreed that he was the anitquarian Cincius, who was the author of:

“... various grammatical and antiquarian treatises, including:

✴de verbis priscis;

✴de comitiis;

✴de fastis;

✴de officio iuricsonsulto;

✴de re militari; and

✴mystagogicon.”

Gino Funiaioli (referenced below, at pp. 371-82) listed 31 surviving fragments from Cincius’ works, the great majority of which survived in Festus’ summary of the lexicon of the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus (including Fr. 25 = ‘De verborum significatu’, 242 Lindsay, which preserves Cincius’ praenomen). Interestingly, Funiaioli did not include this citation of ‘Cincius’ by Livy among his 31 accepted fragments or the two (his fragments 32 and 33) that he attributed to Alimentus.

Cincius’ ‘Mystagogicon’

Funiaioli did attribute another fragment from Festus that related to the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus to the antiquarian Cincius:

“The dictator T. Quintius (sic) wrote that he offered Jupiter a crown of trientem tertium pondo, because he had taken nine cities in nine days and, on the tenth day, had stormed Praeneste. Cincius, in Book II of ‘Μυσταγωγιχων’ (‘Mystagogicon’) says that [trientem tertium pondo] means two and a third pounds in weight”, (Fr. 11 = ‘De verborum significatu’, 498 Lindsay, my translation).

In his parallel account, Livy recorded that, in 380 BC, T. Quinctius Cincinnatus Capitolinus was appointed as dictator to deal with an unexpected Praenestine attack on Rome and, after:

“... capturing two camps and nine towns belonging to the enemy and receiving the surrender of Praeneste [itself], T. Quinctius returned to Rome. In his triumphal procession he carried up to the Capitol the statue (signum) of Jupiter Imperator that had been brought from Praeneste. It was set up in a recess between the chapels of Jupiter and Minerva, and a tablet was fixed to the pedestal recording [Quinctius’] successes. The inscription ran something like this:

‘Jupiter and all the gods granted that the dictator T. Quinctius should capture nine towns.’

Nineteen days after his appointment, [Quinctius] laid down the dictatorship”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 29: 8-10).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 609 and note 2) observed that:

✴Festus was probably correct that the object that Quinctius offered in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus after his triumph of 380 BC was a crown (rather than the statue recorded by Livy); and

✴Festus’ report of the inscription that accompanied this crown might have been a truncated version of the original, which probably recorded that nine towns were taken by storm and a tenth, Praeneste, surrendered.

He argued (at p. 608) that it is likely that Festus’ record of this inscription in the ‘Mystagogicon’ formed the ultimate evidential basis for both:

✴Livy’s narrative account of Quinctius’ dictatorship; and

✴the parallel account by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, of which only a fragment survives:

“Having vanquished the enemy and loaded down his army with countless spoils, T. Quintius (sic), while serving as dictator, took nine cities of the enemy in nine days”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 15: 5).

Livy clearly had a supplementary source for the information that (pace Festus), Praeneste had not been stormed but had surrendered.

Funiaioli’s Fr, 11 is the only surviving fragment that can be definitively associated with Cincius’ ‘Mystagogicon’. However, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 75) argued that another passage by Festus (as epitomised by Paul the Deacon) that related to an inscription in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus had also come from this book (albeit that Paul had omitted the citation):

“The ‘clavus annalis’ was so called because it was figibatur in parietibus (fixed on the wall) of the [temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus] every year, so that the number of years could be reckoned ...” (‘De verborum significatu’, 49 Lindsay, my translation);

Oakley therefore argued (at p. 81, citing Jacques Heurgon, referenced below) that Livy had also relied on Cincius’ ‘Mystagogicon’ when composing his long digression on the clavus annalis’ (above). Duncan MacRae (referenced below, at p. 34) also made this connection and concluded that, in the Mystagogicon’:

“... it is likely that Cincius described the temples of the city of Rome in the form of a tour for visitors. Based on [its] title and [these] two [surviving] fragments, ... [it was probably similar in form to the much later and] more famous ‘Periegesis’ of Greece by Pausanias, [the Greek title of which] holds a double meaning:

✴the teacher of religious mysteries; and

✴a guide for visitors to temples in Greek cities.

... We do not have enough of the [Mystagogicon’] to say much about its selectivity, ([since] both surviving fragments discuss the Capitoline temple), but what we do have suggests that its focus was on the archaic aspects of Roman religious material culture, an interest that is well-paralleled in Pausanias’ work.”

Date of Cincius’ ‘Mystagogicon’

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 81) argued that Cincius probably wrote his account of the clavus annalis having actually seen the archaic inscription in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, and thus before this temple and other structures on the Capitol burned down in 83 BC. However, John Rich (referenced below, at p. 205 and note 78) observed that estimates of the time at which this L. Cincius was writing:

“... have ranged from the early first century BC to the Augustan period; however, Livy certainly knew his writings, since he cites him in another of his rare antiquarian excursuses. ... Cincius’ references to inscriptions on the Capitol [as cited by Livy and Festus] need not imply personal observation before the burning of the Capitol in 83 BC, ... [pace] Heurgon.”

If this is accepted, then we are left with a terminus ante quem of ca. 25 BC, the likely date of Livy’s first ten books.

However, there is some circumstantial evidence that Cicero was aware of this work at an earlier date that this:

✴in 70 BC, in his speech for the prosecution against the rapacious C. Verres, the ex-governor of Syracuse, Cicero accused Verres of having stolen many precious objects

“... from all the sacred edifices of [his erstwhile province]. The result of all this, gentlemen, is that the persons known as ‘mystagogues’, who act as guides to visitors [at Syracuse] and show them the various things worth seeing, have had to reverse the form of their explanations:

•[before Verres], they showed you what things were [at each of these sacred edifices]; but

•now, they explain ... what has been taken away”, (‘Against Verres’, 2: 4: 132, translated by Leonard Greenwood, referenced below, at p. 441); and

✴ in a letter that Cicero sent to Atticus to announce his arrival in his province of Cilicia in 51 BC, he quipped that:

“I reached Laodicea on 31st July. From this day, clavum anni movebis (you must start your reckoning of the year)”, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 108, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, at p. 65).

Of course, there is no hard evidence that either the ‘mystagogues’ of 70 BC or the ‘clavus annalis’ of 51 BC had anything to do with Cincius. However, it is tempting to suggest that the fact that Cicero used such arcane references in these two witticisms might reflect the fact that Cincius’ ‘Mystagogicon’ was relatively well-known, at least by 70 BC, which would mean that it might have pre-dated the burning of the Capitol in 83 BC.

Praetor Maximus

Nicholas Purcell (referenced below, at p. 28) observed that the dating system evidenced in this inscription:

“... shows that the concept of the ‘era’ was known [in the Rome of 304 BC and that it was used as the basis of a system for the] calibration of time that went back more than two centuries. [Most importantly, the choice of dedication of the Capitoline temple as the start of the era celebrated] ... its great synchronism of with ... :

✴the expulsion of [Tarquinus Superbus, which marked the end of the Regal period]; and

✴the foundation of the Republic.

... [Furthermore], it seems hardly likely that [this] calibration system had been fraudulently devised in living memory.”

This dating system had been superseded long before by Pliny’s time, and he had to explain to his readers that ‘204 years post Capitolinam dedicatam’ indicated the 449th year a condita urbe (from the foundation of Rome in 753 BC).

Etruscan Precedent for the Ritual

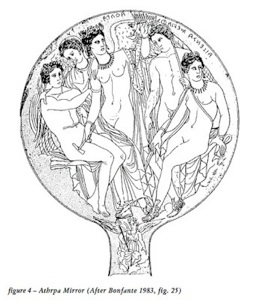

Image from Wayne L. Rupp Jr (referenced below, Figure 4, at p. 213)

According to Livy:

“Cincius, a careful student of monuments of this kind, asserts that at Volsinii also nails were fastened in the temple of Nortia, an Etruscan goddess, to indicate the number of [8] the year.”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 7-8).

This passage by ‘Cincius’, as transmitted by Livy, is our only surviving source for the information that a nail was fixed at the Volsinian temple of Nortia in order to mark the start of the year, presumably as a dating mechanism.

Francesco Roncalli (referenced below, at pp. 225-7) observed that:

“Each of the Etruscan cities must have had its own place where the passing years (and thus the beginning and end of the civic and religious calendar year) was officially registered and ritually sanctioned. It seems significant that only the tradition at Volsinii and the custodian of the rite there, Nortia (whom Livy promoted to the rank of ‘Tuscan goddess’) achieved fame in this context in the Roman world.

✴Perhaps this was because the recording of time at Velzna had pan-Etruscan relevance, possibly because it recorded, among other things, the annual pan-Etruscan councils [at the nearby fanum Voltumna]?

✴Perhaps the role of the priest who was elected by the ‘twelve people’ to preside over these annual councils was analogous to that of the “praetor maximus”at Rome, who (probably following the Etruscan tradition) drove the nail in the cella of Minerva, thereby entrusting ‘his’ year, its collegiate discussions and his own authority, to the inscrutable immutability of destiny ?” (my translation).

The first problem with Cincius’ passage is that, as far as we can tell, Nortia was not a pan-Etruscan goddess: as Henk Versnel (referenced below, at p. 274) pointed out, it seems that Nortia was only worshipped at Volsinii. He cited:

✴the Christian writer Tertulian (ca. 200 AD):

“... [the gods of the Roman provinces] are not Roman, since they are not worshipped at Rome. [Neither are those that] are ranked as deities in Italy by municipal consecration, such as: ... Nortia of Volsinii …” (“Apologeticus pro Christianis”, 24:8); and

✴the satirical poet Juvenal (ca. 120 AD):

“But what of the Roman mob? They follow Fortune, as always, and hate whoever she condemns. [For example]:

•if Nortia (as the Etruscans called her) had favoured Etruscan Sejanus; [and]

•if the old Emperor [Tiberius] had [therefore] been surreptitiously smothered;

that same crowd in a moment would have hailed their new Augustus”, (Satire 10: ‘The Vanity of Human Wishes’).

In this second passage, Nortia is an Etruscan form of the Roman goddess Fortuna, and she was associated with Sejanus (who might have expected to succeed Tiberius, had the mob not killed him) because he came from Volsinii.

Wayne Rupp

The subject matter of the mirror concerns the ill-fated love of two mythological couples:

Turan and Atune; and

Atlenta and Meliacr.

In both cases, the death of the male, which is alluded to by the boar’s head and Athrpa holding the nail of fate, occurred after a boar hunt. This mirror demonstrates a great deal of thematic unity, which is continued even into the exergue. The five figures present in the mirror appear to stand on top of this goddess as if she indicates a ground line and the earth. Here she functions as the setting of the myth and as a chthonic earth goddess, a reminder of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

Remains of the so-called Tempio del Belvedere (ca. 500 BC) at Orvieto

Cincius’ temple of Nortia ??

There is evidence for two ancient temples at Volsinii at which a goddess akin to the Greek Athena (whom the Romans had absorbed as Minerva) was venerated:

✴Temple in Vigna Grande:

Francesco Roncalli (referenced below, at p. 225) and Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2003, at p. 247) noted that the presence of a temple in località Vigna Grande, is indicated by the discovery there of fragments of a frieze (late 6th century BC) that depicted a scene from the the Gigantomachia (Battle of the Giants) in which (in the Greek prototype) Athena defeated Enceladus. (Se also Simonetta Stopponi’s paper of 2104, referenced below, for details of the surviving fragments). The site is at the eastern end of the cliff-top plateau on which Volsinii was built, and was probably immediately outside the walls of the Etruscan city.

✴The so-called Tempio del Belvedere (illustrated above):

•Two inscriptions (CIE 10525 and CIE 10535; 5th century BC; at p. 223) on bucchero cups recorded the epithet ‘apas’ (of the father) might indicate an original dedication to Sur/ Suri.

•A third (CIE 10560; ca. 350 BC; at p. 222) on a black-figure cup recorded ‘Tinia Calusna’: the epithet Calusna (of Calus) suggests a form of Tinia associated with the underworld.

Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2003, at p. 257) discussed these inscriptions, together with a small bronze votive offering from the temple (illustrated to the right) that represents Athena wearing the aegis that had been given to her by Zeus and holding a spear.

However, as Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, 2017, at p. 219. note 37) pointed out, we have no hard evidence that this goddess was identified as Nortia at either temple.

If the analogy is pursued to its logical conclusion, this would suggest that the annual driving of the nail at Velzna had taken place in the right-hand cella of the Tempio del Belvedere (which, as noted above, was analogous to the cella of Minerva in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus at Rome).

This putative tradition would have come to an end at Velzna in 264 BC, when Velzna and its temples were destroyed. However, a number of bronze nails that were discovered along the southern wall of Temple A at the sanctuary at Campo della Fiera might point to the transfer of the tradition to this location. Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2011) has concluded that:

“The most likely interpretation of [these] nails is for architectural terracottas, but the presence of such a large number of specimens raises the appeal to the Volsinian tradition of the clavus annalis, which was [originally] affixed to the temple of the goddess Nortia, recognised by some in the Orvietan Belvedere temple”.

However, it seems to me that there is circumstantial evidence for the identification of the latter temple with Cincius’ ‘temple of Nortia’:

✴Cincius was clearly speaking about a temple in the original city of Volsinii, which the Romans destroyed in 264 BC (albeit that the goddess retained her Etruscan name when her cult transferred to the replacement city at modern Bolsena).

✴As Annalisa Calapà (referenced below, at p. 43) pointed out, Cincius’ record of the similarities between the ritual of the clavus annalis at Rome and at Volsinii:

“ ... suggests that the Etruscan goddess [Nortia] was somehow assimilated to Minerva: this seems to be confirmed by a dedication (AE 1962 0152) to Minerva Nortina found in Visentium, a Roman municipium on the west side of the lake of Bolsena.”

Dictatorship Clavi Figendi Causa

Livy clearly believed that the ancient ritual of fixing the nail, which had originally been used to record the passing years, had evolved over time into an occasional propitiatory ritual of the kind that the Senate mandated in 363 BC. He then gave a short (an not particularly helpful) summary of how this putative evolution had occurred:

“The ceremony ... had subsequently passed from the consuls to dictators, because they possessed greater authority. Then, after the custom had lapsed, the matter was viewed as worthy in itself to warrant the appointment of a dictator clavi figendi causa (for the purpose of fixing the nail)”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 8)

The occasion prior to 363 BC on which a pestilence had been assuaged by a dictator fixing a nail (which, it was said, the older men of 363 BC remembered) had presumably occurred (or was imagined to have occurred) in ca. 400 BC, by which time the annual rite of a dictator fixing the nail had presumably lapsed.

Francisco Pina Polo (referenced below, at p. 39) observed that:

“Livy understood [the appointment of the dictator clavi figendi causa of 363 BC to be] an attempt at recovering a lost rite:

Perhaps this was indeed the case and, maybe, the clavus annalis had ceased to exist, at least from the beginning of the 4th century BC.

However, this could [alternatively] be a case of incorrect interpretation on the part of Livy, who may have [believed incorrectly] that the [occasional] appointment of a dictator specifically for fixing the nail [for propitiatory purposes] meant that the annual ritual [for chronological and/or propitiatory purposes] had ceased to exist [by 363 BC].”

Unfortunately, we have no basis upon which to decide between these alternatives and, if Livy had made a mistake, we have no way of knowing when the annual rite was actually abandoned in Rome. All we can say is that it had certainly been abandoned by the time that Livy was writing, since:

his account of it relied on Cincius’ record of the archaic inscription in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus; and

he seems to have written it for an audience that had never come across it.

However, a few years earlier, Cicero had begun a letter to Atticus as follows:

“I arrived at Laodicea on the 31st of July [51 BC]. From this day, ex hoc die clavum anni movebis (you should move the nail of the year”, (my translation of ‘Letter to Atticus’, 5:15)”.

Here, Cicero suggested that Atticus should measure the year of his (i.e. Cicero’s) stay in Laodicea in the ancient manner. The casual nature of this suggestion indicates that the rite of the clavus annalis was still recalled, at least in some quarters, in the 1st century BC.

Origins of the Dictatorship Clavi Figendi Causa

According to Livy, in the consulship of Lucius Genucius Aventinensis and Quintus Servilius Ahala (365 BC):

“Matters were quiet as regarded domestic troubles or foreign wars, but (lest there should be too great a feeling of security) a pestilence broke out ... The most illustrious victim was Marcus Furius Camillus, whose death, though occurring in ripe old age, was bitterly lamented ... [He] was counted worthy to be named next to Romulus, as the second founder of Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 1: 7-10).

Camillus’ victory at Vell in 396 BC had marked the start of the Roman conquest of Italy, and his death some three decades later must have felt like the end of an era. The epidemic continued into the following year. Attempts were made to placate the gods, but they proved ineffective: in 363 BC, the Tiber broke its banks and flooded the Circus, an event that was taken as a sign of the gods’ continuing displeasure. According to Livy, at this point:

“Older men are said to have remembered that a pestilence had once been assuaged by the dictator [ritually] fixing a nail. The Senate believed this to be a religious obligation, and ordered the appointment of a dictator clavi figendi causa (for the purpose of fixing the nail) ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 4-6).

As Mark Wilson (referenced below, at p. 36) observed, it is not possible to identify the occasion on which this earlier unidentified dictator had been appointed. All we can say is that Livy’s record of the appointment of such a dictator in 363 BC (which, was we shall see, is confirmed by the fasti Capitolini) is the earliest securely-dated record of its kind in our surviving sources.

Read more:

Zuddas E., “La Praetura Etruriae Tardoantica”, in:

Cecconi G. A. et al. (editors), “Epigrafia e Società dell’Etruria Romana: Atti del Convegno di Firenze, 23-24 Ottobre 2015”, (2017) Rome

MacRae D., “Legible Religion: Books, Gods, and Rituals in Roman Culture”, (2-16) Cambridge MA and London

Cornell T. C. (editor), “Fragments of Roman History”, (2013) Oxford

Stopponi S. , “Orvieto, Campo della Fiera: Fanum Voltumnae”, in:

Macintosh Turfa J. (editor.), “The Etruscan World”, (2013 ) Oxford, pp. 632-54

Calapà A., “Sacra Volsiniensia. Civic Religion in Volsinii after the Roman Conquest”, Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, Frankfurt, (2012)

Rich J., “The Fetiales and Roman International Relations”, in:

Richardson J. H. and Santangelo F. (eidtors), “Priests and State in the Roman World”, (2011 ) Stuttgart, at pp. 187-242

Holloway R. R., “Who Were the Tribuni Militum Consulari Potestate?”, L' Antiquité Classique, 77 2008) 107-25

Rupp W. L., “The Vegetal Goddess in the Tomb of the Typhon”, Etruscan Studies, 10:17 (2007) 211-9

Stopponi S., “Volsiniensia Disiecta Membra”, in:

Edlund-Berry I. et al. (editors), “Deliciae Fictiles II: Proceedings of the International Conference held at American Academy in Rome (7th-8th November 2002)”, (2006) Oxford, at pp. 210-221

Roncalli F., “I Culti’, in:

Della Fina G. and Pellegrini E. (editors), “Storia di Orvieto: Antichità”, (20o3) Perugia, at pp 217-35

Stopponi S., “Templi e l' Architettura Templari”, in:

Della Fina G. and Pellegrini E. (editors), “Storia di Orvieto: Antichità”, (20o3) Perugia, at pp 235-73

Shackleton Bailey D. R. (translator), “Cicero: Letters to Atticus, Vol. II”, (1999) Cambridge MA

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume II: Books VII and VIII”, (1998) Oxford

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume I: Book VI”, (1997) Oxford

Versnel H. S., “Triumphus: An Inquiry Into the Origin, Development and Meaning of the Roman Triumph”, (1970) Leiden

Heurgon J., “L. Cincius et la Loi du Clauus Annalis”, Athenaeum, 42 (1964), 432-7

Greenwood L. H. G. (translator), “Cicero: Verrine Orations, Vol. II: Against Verres, Part 2, Books 3-5”, (1935) Cambridge MA

Funaioli G. (editor), “Grammaticae Romanae Fragmenta (GRF)”, (1907) Leipzig,

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)