Roman Pre-History

Collegium Fetialium

Roman Pre-History

Collegium Fetialium

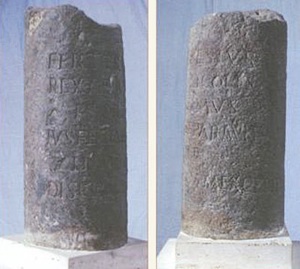

Two views of a cippus (1-50 AD) from the Clivus Palatinus in Rome (now in the Antiquarium Palatino),

which carries an inscription (CIL VI 1302) that can be translated as:

Ferter Resius, king of Aequicola, who first devised the fetial rites, later learned by the Roman people

Collegium Fetialium

Almost everything that we know (or think we know) about the priestly college of fetials comes to us from the surviving works of a small number of historians and antiquarians of the late Republic. The great antiquarian Varro (ca. 45 BC) summarised the received wisdom at that time as follows:

“The fetiales (are so named) because they were responsible for public trust (fides) amongst the people: for it was through them that just war was undertaken and then ended, so that the trust of peace was established by a treaty (foedus):

✴Some of them were sent before a war was undertaken, [in order to] to seek restitution (qui res repeterent).

✴Even now, through them, a treaty is made (fit foedus)”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 5: 86, from the translation by John Rich, referenced below, 2011, at pp. 190-1).

From this, we learn that the fetials:

✴were traditionally associated (inter alia) with the preliminaries necessary to the waging of a just war; and

✴even in Varro’s own time, they were still associated with the solemnisation of peace treaties.

Establishment of the College

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus is our earliest surviving source for the establishment of the fetials’ college. Dionysius tells us that he :

“I arrived in Italy at the very time that Augustus ... brought an end to the civil war [in ca. 29 BC] ... and have lived at Rome from that time to this present day, a period of 22 years, learning the language of the Romans and acquainting myself with their writings ... ”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 7: 2).

It seems, therefore, that he published this work in ca. 7 BC. He included the fetials among eight priestly colleges that were founded by Rome’s second king, Numa Pompilius (traditionally 715-672 BC):

“... having committed his [new] system of religious laws to writing, Numa divided them into eight parts, that being the number of the different classes of religious ceremonies [in Rome at that time]. He assigned the first division of religious rites to the 30 curiones, who ... perform the public sacrifices for the curiae. ...”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 63: 4).

The recipients of the other seven divisions of religious rites were: flamens; the commanders of the celeres (royal bodyguard); augurs; Vestal Virgins; Salii; fetials; and pontiffs. In relation to the fetials, he recorded that:

“The seventh division of [Numa’s religious rites] was devoted to the college of the fetials; these may be called in Greek εἰρηνοδίκαι or ‘arbiters of peace’." They are chosen men, from the best families, and exercise their holy office for life; King Numa was ... the first who instituted this holy magistracy among the Romans. But whether he took his example from those called the Aequicoli, according to the opinion of some, or from the city of Ardea, as Gellius [see below] writes, I cannot say. It is sufficient for me to state that before Numa's reign, the college of the fetials did not exist among the Romans”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 72: 1-2).

Cicero

The statesman Cicero, who served as consul in in 63 BC, is our earliest surviving source for Numa’s religious innovations. The relevant reference is in Book II of his ‘On the Republic’, which he had finished in late October 54 BC, as he mentioned in a letter of that date to his brother Quintus (Letters to Quintus, 25: 1, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, at p. 181). By this time, Cicero was no longer at the centre of public life, and he therefore tried to influence affairs as an author. In this critique of the state of the Republic, he put his own thoughts into the mouth of Scipio Aemilianus, and they were uttered in a dialogue that took place in 129 BC. As Anthony Everitt (referenced below, at p. 172) pointed out:

“This timing was highly appropriate, for the stormy career of Tiberius Gracchus was recent history. Cicero believed that [Gracchus’ tribuneship of 133 BC] ... had introduced the long constitutional crisis that, ... [at his time of writing], was coming to a head.”

In Book II, Cicero set out to demonstrate that the constitution of the Roman Republic, as Scipio would have known it:

“... was superior to those of other States on account of the fact that ... it was not based upon the genius of one man, but rather of many, and it was founded ... over many centuries and many generations”, (‘On the Republic’, 2: 2).

This process had begun with Romulus:

“What State's origin is so famous or so well known to all men as the foundation of this city by Romulus ?”, (‘On the Republic’, 2: 4).

He summarised Romulus’ contribution as follows:

“Romulus had reigned 37 years, and established those two excellent foundations of our Republic: the auspices; and the Senate”, (‘On the Republic’, 2: 17).

Romulus’ successor, Numa instilled in the previously warlike Romans:

“... a love for peace and tranquillity, which enables justice and good faith to flourish most easily ... [He] also instituted the greater auspices (auspiciis maioribus inventis), added two augurs to the original number, and put five pontiffs, selected from the most eminent citizens, in charge of the religious rites. Furthermore, by the introduction of religious ceremonial, through laws that still remain on our records, he quenched the people’s ardour for the warlike life to which they had been accustomed. He also appointed flamens, Salii, and Vestal Virgins, and established all the branches of our religion with the most devout solicitude ... By the institution of such customs as these, he turned the thoughts of ... [the Romans] toward benevolence and kindliness. Thus, when he had reigned for 39 years in complete peace and harmony, ... he died, after having established the two elements that most conspicuously contribute to the stability of a State: religion; and the spirit of tranquillity”, (‘On the Republic’, 2: 26-7).

Cicero’s list includes six of Dionysius‘ priesthoods: only the commanders of the celeres and the fetials were not mentioned. However, he assumed the existence of the fetials in the following reign (see below), which probably indicates that he attributed the foundation of their college to Numa.

Livy

Livy is the other important late Republican source for Numa’s religious innovations (and much else besides). Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 110) argued that the first five books of his seminal ‘History of Rome’ were probably started before the battle of Actium (31 BC) and published in their final form in ca. 27 BC. Livy recorded that Numa:

“... appointed a flamen for Jupiter, ... [and] added two other flamens, one for Mars, the other for Quirinus. In like manner he designated virgins for Vesta's service ... He likewise chose twelve Salii for Mars Gradivus ... He next chose as pontifex Numa Marcius, son of Marcus, one of the senators, and to him he entrusted written directions ... for performing the religious rites ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 20: 4-5).

Christopher Smith (referenced below, at p. 353) observed that Livy must have known of the tradition followed by Dionysius since:

“... he attributes to Numa the following institutions: flamines; Vestals; Salii; [and] pontfices, in other words, four of [Dionysius’] eight and in the same order.”

Like Cicero, Livy assumed the existence of the fetials in the following reign (see below), which probably indicates that he also attributed their foundation to Numa.

Archaic Iura Fetialia

From Varro’s testimony (above), it seems that the fetials were originally responsible for a series of rituals associated with war and peace. John Rich (referenced below, 2011, at p. 190) cautioned that:

“Some writers, [both ancient and modern], credit them with a wider role, [including] carrying out a judicial function and even playing a part in the determination of policy. ... The case is presented in its most extreme form by Dionysius of Halicarnassus ..., [whose] conception of the fetials is reflected in the Greek equivalent he uses for them, doubtless of his own devising: they were εἰρηνοδίκαι, ‘arbiters of peace’. ... To a considerable extent, his statements must represent his own reinterpretation of the fetials’ ritual activities.”

Much of the discussion below will thus revolve around the fetial rituals in relation to the diplomacy of war and peace.

These rituals would have been prescribed in a series of iura fetialia: for example, according to Livy, when Cnaeus Manlius claimed a triumph over the Galatians in 187 BC, his opponents’ case against him included the charge that he had violated the established procedures in waging this war. They asked him rhetorically:

“Do you, [Manlius], wish ... the fetial laws (fetialia iura) to be done away with and the fetials themselves abolished?”, (‘History of Rome’, 38: 46: 10-11).

John Rich (referenced below, 2011, at p. 191) observed that:

“The term ius fetiale ... [is sometimes translated as] ‘fetial law’. ... [It has been considered to be] comparable to the bodies of law associated with the augurs and pontiffs (ius augurale, ius pontificium), and scholars have often interpreted it as having a [similarly] wide scope. ... However, the term [‘ius fetiale ‘] is usually applied by our sources only to ritual preliminaries of war, and thus the translation ‘law’ may mislead.”

He therefore preferred to translate the term ‘ius fetiale’ as ‘fetial rule’, which would have prescribed one of the fetial rituals. Although Livy (above) was concerned primarily with Manlius’ alleged neglect of the correct preliminaries of war, his reference to the iura fetialia (in the plural) makes it clear that the fetials were also responsible for other rituals. Furthermore, in the light of the testimony of Varro (above), we might reasonably assume that another ius fetiale related to the ritual solemnisation of treatie. This is further supported by Suetonius’ testimony that the Emperor Claudius (41 - 54 AD), who was a noted antiquarian:

“... struck his treaties with foreign princes in the Forum, sacrificing a pig and reciting the ancient fetial formula (vetere fetialium praefatione)”, (‘Life of Claudius’, 25: 5).

In the following sections, I explore how our surviving sources described the inception of these fetial rituals in the Regal period or, more specifically, in the reigns of the third and fourth kings of Rome:

✴Tullus Hostilius (traditionally 672-642 BC); and

✴Ancus Marcius (traditionally 672-616 BC)

Fetials in the Reign of Tullus Hostilius

Cicero: Ius Fetiale for the Preliminaries of War

The earliest reference in our surviving sources to a ius fetiale is by Cicero (54 BC), in Book II of his ‘On the Republic’ (discussed above). At the start of his account of constitutional developments under Tullus, Cicero noted that he:

“... excelled in military skill and mighty deeds of war; ... he established the rule (ius) by which wars were declared (bella indicerentur) which, once he himself had created it most justly, he sanctioned by the fetial rites (sanxit fetiali religione), so that all war that had not been announced and declared (denuntiatum indictumque) was judged to be unjust and impious”, (‘On the Republic’, 2: 31, based on the translation by Hannah Cornwell, 2014, referenced below, at p. 41, note 2).

Thus, a just war required a denuntatio and an indictio, and these were clearly separate things, albeit that they were closely related. We can get an idea of what Cicero meant here from a speech that he gave in 43 BC, in which he tried to justify the Senate’s decision to send an embassy to the rebellious Mark Antony at Mutina rather than to declare war against him:

“And yet, Romans, that is not an embassy (legatio) but rather a declaration of war if he does not obey (denuntiatio belli, nisi paruerit): the decree reads as though envoys (legati) were being dispatched to Hannibal”, (‘Philippics’, 6: 2: 4).

In other words, according to Cicero, Tullus devised the ius fetiale that prescribed the ritual preliminaries to the waging of a just war, which involved an ultimatum and, if this was rejected, a formal declaration of war.

It is not immediately obvious to a modern reader why Cicero attached so much significance to this innovation. However, the reason might be found in an observation that Dionysius made for his Greek readers:

“... since the college of the fetials is not in use among the Greeks, I think it incumbent on me to relate how many and how important were the matters that fell within its jurisdiction, so that those who are unacquainted with the piety practised by the [Romans of the Regal period might understand why] all their wars had the most successful outcome; for it will appear that the origins and motives of all of them were most holy and, for this reason especially, the gods were propitious to them in the dangers that attended them”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 2: 72: 3).

For a Roman of Cicero’s time, it would go without saying that the divine approbation that the Romans had enjoyed by virtue of their careful adherence to the appropriate rituals of war had played a major part in their evolution from the warlike band led by Romulus to the all-conquering Roman Republic of Scipio’s time.

Unfortunately, the passage quoted above is almost all that survives of Cicero’s account of the reign of Tullus: the next seven lines describe how Tullus sought and received the approval of the people before assuming the insignia of royalty, but this is followed in the surviving manuscripts by a lacuna of about 15 lines. It is therefore impossible to determine whether Cicero described the circumstances in which Tullus had devised this ius fetiale. However, the most significant event with which Tullus was associated in Roman tradition was his destruction of Alba Longa, which had been founded by Ascanius, the son Aeneas and the grandson of Latinus. Earlier in his account, Cicero had recorded that, after Romulus’ birth there:

“... they say that Amulius, the Alban king, fearing the overthrow of his own royal power, ordered him, with his brother Remus, to be exposed on the banks of the Tiber. There he was suckled by a wild beast from the forest, and was rescued by shepherds ... When he grew up, we are told that,... [his qualities were such] that all who then lived in the rural district where our city now stands were willing and glad to be ruled by him. After becoming the leader of such forces as these (to turn now from fable (fabulae) to fact (facta)), we are informed that, with their assistance, he overthrew Alba Longa, a strong and powerful city for those times, and put King Amulius to death. After doing this glorious deed he conceived the plan, it is said, of founding a new city [called Rome on this site] ...”, (‘On the Republic’, 2: 4).

In other words, for Cicero, Romulus’ overthrow of Amulius of Alba was the first ‘fact’ in the constitutional history of the Republic. However, the Romans did not believe that Romulus destroyed Alba: for example, Livy recorded that, after Romulus and Remus had killed Amulius, they:

“... hailed their grandfather, Numitor as king ... The Alban state being thus made over to Numitor, Romulus and Remus were seized with the desire to found a city in the region where they had been ... raised”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 6: 2-3).

Alba was to dominate Latium until Tullus destroyed it and incorporated its citizens into the Roman state. This was a pivotal moment in Roman tradition: the Romans could now claim a direct link to Aeneas, and the way was open for them to become the dominant political force in Latium. It is therefore highly likely that this ‘fact’ was recorded in the now-lost part of Cicero’s account of his reign, particularly since we know that it ended with another comparison of the reigns of Tullus and Romulus: according to St Augustine:

“Cicero, in [‘On the Republic’] says of Tullus Hostilius, ... who was [killed] by lightning, that:

‘he was not considered to have been deified [after] his death, possibly because the Romans were unwilling to undermine the ... [alleged deification] of Romulus, lest they should bring it into contempt by gratuitously assigning it to all and sundry’”, (‘City of God’, 3: 15).

John Rich (referenced below, 2011, at p. 212) argued that:

“Cicero must have had some authority for associating:

✴the tale of how Tullus’ war with Alba began; with

✴the introduction of the fetial ius [for the preliminaries of war];

and this may well have been how the early Roman historians portrayed it.”

As it happens, we can almost certainly identify Cicero’s source for his information on the ius fetiale (and for the rest of Book II): Graham Sumner observed that:

“At [‘On the Republic’] 2: 1: 1-3, [Scipio] says that his discourse is derived from the elder Cato and that, in accordance with Cato's own practice, it will go back to the origo of the Roman people. Thus, Cicero delicately indicates his main source, Cato's historical work ‘Origines’.”

Cato probably wrote this work in his old age, which would date it to ca. 150 BC. The work is now lost, but another passage from it that was apparently cited by the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus in his ‘De verborum significatu’ does indeed relate to Tullus’ war with Alba. The date at which Flaccus compiled his lexicon is unknown, but we know that he acted as tutor to the grandchildren of the Emperor Augustus in the late 1st century BC, and that he died at an advanced age in ca. 20 AD. The original work is lost, but:

✴a scholar called Festus summarised it in the 2nd century AD; and

✴missing parts of Festus’ work can be partially recovered from a summary of it that Paul the Deacon wrote in the 8th century AD.

(All the passages discussed below from both Festus and Paul are from the manuscripts edited by Wallace Lindsay, referenced below). The Catonian passage under discussion here is cited in Festus’ summary of Flaccus’ entry on the word ‘oratores’ when it is applied to ‘gentes qui missi’ (those who were sent):

“... [some] Roman writers refer to [such men as oratores] rather than as legati: [for example], Cato [wrote] ... in book 1 of his ‘De Origines’:

‘... For that reason war began. Cluilius, the Alban praetor, sent oratores to Rome with …’’’, (‘De verborum significatu’, p. 196 L, translated by Timothy Cornell, in Timothy Cornell (Ed.), referenced below, Volume II, at p. 169).

As we shall see, the chain of events that led up to Tullus’ war with Alba began when Cluilius (whom Cato designated as the Alban praetor or chief magistrate) sent legates to Rome to demand restitution after alleged Roman raids on his territory. It is therefore at least possible that Cato’s narrative in Book 1 of the ‘Origines’ recorded that Tullus established the ius fetiale, as Cicero described it, either:

✴when he embarked on his diplomatic exchanges with Cluilius (as John Rich assumed); or

✴at some time thereafter.

Preliminaries to Tullus’ War with Cluilius of Alba

Three surviving sources, all dating to the last three decades of the 1st century BC, contain complete or essentially complete accounts of the preliminaries of Tullus’ war with Alba.

Diodorus Siculus

The only known work of the Greek-speaking historian Diodorus Siculus, which he entitled the ‘Bibliotheke’, set out to describe the entire history of the known world up to his own time. Charles Muntz (referenced below, at pp. 3-4) described the scant biographical information that still survives: importantly, Diodorus himself (at 1: 4: 2-3) revealed that he had spent a long period at Rome, where he had found excellent resources for his research. Furthermore, other indications from his narrative suggest that:

✴he arrived at Rome before 45 BC (when the Rostra was still outside the Senate); and

✴his work was completed before Octavian’s victory at Actium (since he referred to the Ptolemies, the dynasty to which Cleopatra belonged, as the most recent dynasty to rule Egypt).

Since nothing is known about him after Actium, we might reasonably assume that he is the earliest of our three surviving sources.

The relevant part of Diodorus’ work is now lost, but an unknown source preserved the following fragment:

“While Tullus Hostilius was king of the Romans, the Albans ... claimed that the Romans had seized part of their territory. They duly sent ambassadors to Rome to demand justice and, should the Romans ignore their demands, to declare war. However, [Tullus] ... gave orders that his friends should receive the [Alban] ambassadors and invite them to be their guests, while he would avoid any meeting with them. [Meanwhile], he sent men to the Albans to make similar demands of them. ... By good fortune, his ambassadors to Alba were the first to be refused justice, and they therefore declared war for the 30th day following. Thus, when the Alban ambassadors [eventually managed to present] their demands [to Tullus], he replied that, since the Albans had been the first to refuse justice, the Romans had [already] declared war upon them. Such, then, was the reason why these two peoples, who enjoyed mutual rights of marriage and of friendship, entered into hostilities with each other”, (‘’Library of History’, presumed fragments of 8: 25: 1-4).

Livy

Livy’s description of the procedure by which the Romans declared war on Alba is almost identical to that of Diodorus: Tullus distracted the Alban legati while he:

“... sent [legati to Alba] res repetiverant (seeking restitution) and, being denied it, they made a declaration of war for the 30th day”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 22: 5).

As we shall see, after the death of Cluilius (whom Livy recorded as the king of Alba), Mettius Fufetius (whom Livy recorded as the dictator of Alba) avoided hostilities by negotiating a truce. During these negotiations, Mettius looked back on how events had come to this pass, recollecting that Cluilius had said that:

“... the cause of the war had been the injuries [inflicted] and the failure to return things demanded in accordance with our treaty (non redditas res ex foedere quae repetitae ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 23: 7).

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius might well have known of Diodorus’ work and he must have come across Livy, albeit that he mentioned neither among his sources. Nevertheless, although his account is significantly longer than either of theirs, it does not tell a fundamentally different story.

According to Dionysius, when the Alban ambassadors arrived at Rome:

“... Tullius suspected that they had come to demand satisfaction ... , since there existed a treaty between the two cities that had been made in the reign of Romulus, which stipulated, among other things, that neither of them should begin a war: if either complained of any injury whatsoever inflicted upon them by the other, that city would demand satisfaction ... and, if it failed to obtain it, then the treaty would be considered as already broken, and the offended city could then make war as a matter of necessity”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 3: 1).

Tullus therefore arranged for the Alban ambassadors to be distracted and:

“... sent to Alba some Romans of distinction, duly instructed as to the course they should pursue, together with the fetials, to demand satisfaction from the Albans for the injuries the Romans had received. These, having performed their journey before sunrise, found [the Alban chief magistrate], Cluilius, in the forum at the time when the early morning crowd was gathered there. Having set forth the injuries that the Romans had received at the hands of the Albans, they demanded that he should act in conformity with the treaty between the cities”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 3: 3).

In this passage, Dionysius departed from the accounts of Diodorus and Livy in the following respects:

✴he embedded the treaty between Rome and Alba in his narrative of the diplomatic preliminaries to war;

✴he mentioned in passing that the distinguished Romans whom Tullus sent to Alba were accompanied by ‘the fetials’; and

✴he placed the Roman ambassadors’ meeting with Cluilius in the Alban forum.

He then embarked on an elaborate account of the debate between Cluilius and ‘the leader of the [Roman] embassy’, which need not detain us. The crux of his subsequent account was that:

✴when Cluilius rejected the Roman demands, the leading Roman ambassador warned that:

“... I call the gods, whom we made witnesses of our treaty, to witness that the Romans, having been the first to be refused satisfaction, will be undertaking a just war against the violators of that treaty ... Since you , [Cluilius], were the first called upon for satisfaction and also the first to refuse it, and since you have [nonetheless] been the first to declare war against us, [you should expect] swift vengeance to come upon you from the [Roman] sword”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 3: 5); and:

✴Tullus waited until he received news that Cluilius had refused the Roman demands before he finally summoned the Alban ambassadors and duly announced that:

“... having obtained nothing [by way of restitution] that the treaty [between us] directs, I declare against the Albans a war that is both necessary and just”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 3: 6).

In these passages, Dionysius departed from the accounts of Diodorus and Livy in two further respects:

✴when Cluilius refused to meet the Roman demands, the Roman ambassadors merely threatened war, and it was Tullus himself who declared it; and

✴there is no indication here that this declaration was ‘for the 30th day’.

It seems to me that Dionysius probably added a number details to the established tradition in an attempt to reconcile this account with his generalised account of the fetial ritual in Numa’s time (discussed below): these include:

✴the location of the Roman ambassadors’ meeting with Cluilius in the Alban forum;

✴the passages in direct speech attributed to the leading ambassador and to Tullus; and

✴his failure to record that war was declared for the 30th day.

Furthermore, his passing reference to the presence of fetials in the Roman embassy to Alba, which was apparently little more than an after-thought, was probably necessitated by his earlier insistence that fetials had been involved in the ritual preliminaries of war since the reign of Numa (as discussed below).

Preliminaries to Tullus’ War with Cluilius of Alba: Conclusions

The story of the competing demands for restitution made by Cuilius and Tullus on this occasion was clearly well-established in Roman tradition and dated back at least as far as Cato (ca. 150 BC). However, Diodorus, Dionysius and Livy each offered a different explanation of the fact that both Tullus and Cluilius felt it necessary to send ambassadors to demand restitution before declaring war:

✴Diodorus interrupted his narrative to explain that Tullus sent ambassadors to Alba:

“... in pursuance of an ancient custom, because men of ancient times were concerned about nothing else so much as that the wars that they waged should be just ones; for, he was worried that, if he were unable to discover the men responsible for the robbery and to hand them over to those who demanded them, it would be thought that he was entering upon an unjust war”, (‘’Library of History’, presumed fragments of 8: 25: 3).

In other words, Diodorus (or his source) assumed that, under the accepted conventions of war in Latium at this time, if Tullus had refused, for whatever reason, to comply with the demands conveyed by the Alban ambassadors as soon as they were made, then they would have had right on their side if they had declared war on Rome.

✴Dionysius claimed that ambassadors were sent in accordance with the terms of an extant treaty and, when Cluilius rejected the Roman demands, the leading Roman ambassador called on:

“... the gods, whom we made witnesses of our treaty, to witness that the Romans, having been the first to be refused satisfaction, will be undertaking a just war against the violators of that treaty ...”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 3: 5).

Thus, for Dionysius, these diplomatic exchanges had little to do with local public opinion: what mattered was that the Albans could be shown to have offended the gods by violating the treaty that they had witnessed.

✴Livy came somewhere in the middle:

•At the start of his main account, he recorded that Tullus and Cluilius sent legati at the same time, but:

“... Tullus had commanded his envoys to ... [carry out] his orders [immediately]; he felt convinced that the Albans would refuse his demands, in which case he would be able to declare war in good conscience (pie bellum indici posse)”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 22: 4).

This seems to reflect the tradition followed by Diodorus.

•However:

-later in this part of his account, when Tullus heard that Cluilius had, indeed, refused his demands, he summoned the Alban legati and ordered them to:

“Tell your king that the Roman king calls the gods to witness [that the Albans] first spurned the Romans’ demand for restitution (res repetentes) and dismissed their legati, so that they [i.e. the gods] may call down all the disasters of this war upon the guilty nation”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 22: 7); and

-in his account of Tullus’ subsequent negotiations with Mettius, he had the latter recollect that:

“... the cause of the war had been the injuries [inflicted] and the failure to return things demanded in accordance with our treaty (non redditas res ex foedere quae repetitae) ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 23: 7).

This seems to reflect the tradition followed by Dionysius, in which ambassadors had been sent in accordance with the treaty, and Tullus had acted in a way that would ensure that the Albans violated it, albeit unintentionally, thereby incurring the wrath of the gods.

It seems to me that the most economical explanation for these differences is that:

✴Diodorus and Livy drew on the same tradition for their accounts of the competing embassies sent by Tullus and Cluilius;

✴Livy became aware of the tradition of Romulus’ treaty with Alba only after his account of these diplomatic exchanges was complete; and

✴Dionysius subsequently merged the two traditions into a relatively coherent (albeit rambling) narrative.

It seems certain that the descriptions by Diodorus, Livy and Dionysius of the competing demands of Cluilius and Tullus for restitution ultimately derived from a common source. Diodorus and Livy agreed that the procedure by which the Romans declared war was (in Livy’s words) as follows:

“... [Tullus] sent [legati to Alba] res repetiverant (seeking restitution) and, being denied it, they made a declaration of war for the 30th day”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 22: 5).

Dionysius’ account is elaborated:

✴Tullus sent ambassadors, accompanied by fetials, to demand restitution;

✴Cluilius rejected the Roman demands and ordered the Roman ambassadors to leave Alba;

✴the chief ambassador called on the gods to witness this unjust act and warned that Roman vengeance would follow; and

✴Tullus declared war (not, apparently, for the 30th day).

Despite these differences in detail, the procedures are equivalent in their fundamentals: the Romans delivered an ultimatum and, when it was rejected, they declared war. The key points for the present analysis are that:

✴neither Diodorus (as far as we know) nor Livy suggested that any of the members of the Roman embassy that Tullus sent to Alba were fetials:

•the case of Diodorus is uncertain, because of the indirect way in which his testimony has come down to us; but

•the case of Livy is clear and also unsurprising, since, as we shall see, he believed that the fetials only became involved in the ritual preliminaries of war in the reign of Tullus’ successor; and

✴Dionysius only mentioned the fact that they accompanied the Roman ambassadors in passing.

None of these three sources claimed that the Romans declared war on Alba using the ritual prescribed by the ius fetiale.

We should now look again at Cicero’s assertion that Tullus:

“... established the rule (ius) by which wars were declared (bella indicerentur) which, once he himself had created it most justly, he sanctioned by the fetial rites (sanxit fetiali religione), so that all war that had not been announced and declared (denuntiatum indictumque) was judged to be unjust and impious”, (‘On the Republic’, 2: 31, based on the translation by Hannah Cornwell, 2014, referenced below, at p. 41, note 2).

I argued above that Cicero’s ‘denuntiatio’ implied the delivery of an ultimatum demanding restitution, the rejection of which would trigger an ‘indictio’ (declaration of war). This is consistent with the fundamentals of the procedure described by Diodorus, Livy and Dionysius: in Livy’s words:

“... [Tullus] sent [legati to Alba] res repetiverant (demanding restitution) and, being denied it, they made a declaration of war for the 30th day”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 22: 5).

However, as discussed above, given the long lacuna that now follows in the surviving manuscripts, we do not know whether Cicero associated Tullus’ establishment of the ius fetiale with his declaration of war on Alba. That brings us back to Cato. As we have seen:

✴Cicero almost certainly took his description of Tullus’ ius fetiale from Cato’s ‘Origines’; and

✴we know from Festus/ Flaccus that Cato described Tullus’ war with Alba in Book 1 of this work.

It is therefore at least possible that Cato’s narrative in Book 1 of the ‘Origines’ recorded that Tullus established the ius fetiale, as Cicero described it either:

✴when he embarked on his diplomatic exchanges with Cluilius (as John Rich assumed); or

✴at some time thereafter.

Diodorus, Livy and Dionysius must all have been aware of Cato’s ‘Origines’, and Dionysius even cited Cato among his important sources (at ‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 7: 3). It seems to me that the most economical assumption on the basis of these observations is that:

✴the accounts by Diodorus, Livy and Dionysius of the first phase of the war were not fundamentally different from that by Cato; but

•Cato, followed by Cicero, recorded that Tullus had established the ius fetiale in the form that Cicero described it at some time after his victory over Alba; while

•Livy and Dionysius each followed a different tradition (as we shall see).

In the section on Tullus’ war with the Latins (below), I argue that the most likely scenario is that Cato had recorded that Tullus had devised the ius fetial when he came to terms with the other Latin communities.

Solemnisation of Tullus’ Treaty with Mettius Fufetius of Alba

According to Livy, after the Romans’ declaration of war on Alba for the 30th day:

“The Albans, who were first in the field, invaded the Roman territory with a large army ... [and] established their camp not more than five miles from the City ... [It was] in this camp [that] Cluilius, the Alban king, died, and the Albans chose as dictator Mettius Fufetius”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 23: 3-4).

Tullus responded by leading his army into Alban territory. Mettius duly followed him, having sent a legatus ahead to propose that they should confer before hostilities began. Tullus agreed, and Mettius began by warning that the Etruscans, their common enemy, would surely take advantage of the forthcoming battle to attack them both. The two men therefore agreed to resolve their differences in a proxy war that involved a duel between their respective champions (two sets of triplets, the probably Roman Horatii and the probably Alban Curiatii). Then, according to Livy:

“Before proceeding with the battle, a treaty was made between the Romans and the Albans, providing that the nation whose citizens triumphed in this contest would hold undisputed sway over the other nation”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 24: 3).

Dionysius gave a very similar account of the subsequent defusing of tension: after Cluilius’ unexpected death, Mettius Fufetius:

“... decided to invite the enemy to an accommodation, taking the initiative himself in sending heralds, after he had been informed of a danger from the [Veientes and Fidenates] that threatened both the Albans and Romans, a danger that, if they did not end their war by [a new] treaty, was ... bound to destroy both armies”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 5: 4).

Interestingly, although Dionysius referred to this treaty again at two other points in his narrative (at ‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 9: 45; and 3: 10: 2), he did not describe the procedure by which it was solemnised. However, Livy described this procedure in great detail. He first suspended his narrative account to observe that:

“One treaty differs from another in its terms, but the same procedure is always employed. On the present occasion, we are told that they did as follows”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 24: 3-4).

From this, it seems that Livy had:

one or more antiquarian sources that described the procedure for the striking of treaties in general terms; and

one or more annalist sources that described the procedure by which the treaty agreed by Tullus and Mettius was struck.

Livy then observed that:

“... tradition has not preserved the memory of a more ancient treaty (vetustior foederis)’”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 24: 4).

He could not have meant here that this was the oldest treaty preserved in Roman tradition: he had already recorded that:

✴Romulus had struck a treaty with the Sabine king Tatius (1: 13: 4) and renewed the Romans’ treaty with Lavinium (1: 14: 3);

✴Numa had opened his reign by striking treaties with all of Rome’s neighbours (1: 19: 4); and

✴as we have seen, a treaty between Rome and Alba was apparently still in force when the dispute under discussion here erupted (1: 23: 7).

It seems, therefore, that he meant that the Roman procedure for striking treaties, which he was about to describe, first appeared in Roman tradition in the context of this treaty between Tullus and Mettius.

Livy’s description of this customary procedure began in Rome, when:

“The fetial asked King Tullus:

‘Dost thou command me, King, to make a treaty with the pater patratus [see below] of the Alban People?’”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 24: 4)

This is the first occasion on which Livy referred to the fetials, although, as Robert Penella (referenced below, at p. 233) pointed out:

“... both the fetial priesthood and the procedure for making a foedus appear [here] as established facts of Roman life.”

Since this passage is clearly specific to Tullus’ treaty with Alba, Livy might have taken it from an annalistic source. However, it seems to me that it was more probably his own free composition, designed to introduce the ritual procedures that he was about to describe: we might have expected that the fetial had asked this question at the start of the ritual for solemnising this treaty, but Livy actually digressed at this point by taking to story back to Rome in order to describe the ritual by which fetials were mandated to officiate on occasions such as this.

Livy: Ritual for Mandating Fetial Legates (1: 24: 4-6)

As Livy described it, this ritual involved a series of exchanges between an unnamed king and an unnamed fetial:

“Having been commanded (iubente) by the king [to leave Rome in order to strike a treaty, a fetial] said:

‘I demand (posco) of you the sagmina (sacred herbs).’

The king replied:

‘Take them, untainted.’

The fetial then brought a pure herb of grass (graminuis herba pura) from the arx (citadel) and asked the king:

‘Do you, King, grant me, with my emblems and my companions (vasa comitesque), royal sanction to serve as nuntius (messenger) for the Roman People of the Quirites?’

The king replied:

’So far as it may be done without prejudice to myself and the Roman People of the Quirites, I grant it.’”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 24: 4-6).

Livy probably took this passage from an antiquarian source that was couched in general terms, albeit that he used reported speech in places (‘the fetial said’; ‘the king replied’; etc) in order to relate it to ‘the present occasion’.

Livy offered no explanation for the nouns sagmen/ sagmina and verbena/ verbenae (both of which usually appear in the plural). However, Varro referred to the verbanae in his now-lost ‘De vita populi Romani’ (ca. 43 BC): according to Nonius Marcellus (ca. 400 AD):

“Varro, in his de Vita populi Romani II, declared that the caduceus [the herald’s wand] was the symbol of peace:

‘[We know that] the verbenatus carried the verbena; thus, the caduceus, which we equate with the staff of Mercury, was [in fact] the sign of peace’” (from Nonius’ ‘Doctrina’, at p 848 Lindsay edition, based on the translation of Hannah Cornwell, referenced below, 2015, at p. 340).

The jurist Aelius Marcianus (early 3rd century AD) referred to the sagmina in a similar context in a passage from the 4th book of his ‘Rules’ that is known to us from its inclusion in the ‘Digest of Justinian’:

“‘Sanctum' [sanctified, made sacred and thus inviolable] is derived from the word sagmina, [which refers to] certain herbs that legati of the people of Rome customarily carry to ward off outrages [against their person], just as legati of the Greeks carry things that are called cerycia (κηρύκεια)”, (‘Digest’, 1: 8: 8: 4, translated by Alan Watson, referenced below, at p. 25).

Thus, it seems that, when fetials served as legati, one of them, who was known as the verbenatus (or, more probably, verbenarius - see below), carried the sagmina/ verbenae as a symbol of what we would call their diplomatic immunity.

Flaccus apparently defined the sagmina in his lexicon. Festus’ original entry on this term is now fragmentary, and is best discussed on the basis of Paul’s epitome of it:

“Sagmina was a term once used for the herbs verbenae, because they were brought from a sacred place when legati set out to make a treaty (foedus faciendum) or to declare war (bellumque indicendum)”, (‘De verborum significatu’, p. 425 L, translation by Eric Warmington, referenced below, at p. 59).

This indicates that the ritual under discussion here was used to mandate fetials, not only to make a treaty (as here), but also to declare war. Pliny the Elder (1st century AD) recorded the ritual in the latter context in a passage on the importance of certain plants in Roman history:

“... the authors and founders of Roman power (auctores imperii Romani conditoresque) derived almost boundless benefits from ... :

✴the ‘sagmen’ that they employed at times of public calamity; and

✴the ‘verbena’ of our sacred rites and legations.

Undoubtedly, these two names originally signified the same thing: a grass (gramen) torn up from the arx with the earth attached to it; and hence, when legati were dispatched to the enemy per clarigationem - that is, with the object of clearly demanding restitution of stolen property (id est res raptas clare repetitum) - one of these officers was always known as the verbenarius, (‘Natural History’, 22: 3).

Livy is our only surviving source for the ritual procedure by which fetial legati were mandated in the Regal period, and this is his only reference to its use in the Regal period. However it seems that it was used more generally to mandate the fetials who were to be sent to other communities as representatives of Rome in order:

✴to solemnise treaties (Livy, Varro, Flaccus);

✴to demand restitution (Pliny the Elder); or

✴to declare war (Flaccus).

It also seems that legations such as these would have included a fetial known as the verbenarius (Varro, Pliny the Elder, Marcianus) who:

✴presumably collected the sagmina/ verbenae during the ritual under discussion here;

✴used them to brush the head of another fetial who was to act as pater patratus (Livy); and

✴carried them as a symbol of the inviolability of the legation (Varro, Marcianus).

Fetial Ritual for the Solemnisation of Treaties (1: 24: 6-9)

Livy then turned to what was probably an annalistic source for the information that:

“The fetial [whom Tullus had mandated in the ritual above] was Marcus Valerius, and he made Spurius Fusius pater patratus, touching his head and hair with the verbena”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 24: 6).

John Rich (referenced below, 2011, at pp. 189) considered the names M. Valerius and Sp. Fusius to be ‘evident inventions’, and suggested that the fetial whom Livy named as M. Valerius was known as the verbenarius (the fetial legate who carried the sagmina/ verbenae). As we have seen, he was mandated as nuntius (messenger) for the Roman People of the Quirites. This passage by Livy is our only surviving source for the information that the putative verbenarius made his colleague pater patratus by touching his head with the verbenae. Livy then belatedly explained that:

“The pater patratus is appointed to pronounce the oath (ius iurandum patrandum): that is, to solemnise the treaty (sanciendum ... foedus)”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 24: 6).

Livy now embarked on a generalised account of the fetial ritual for the solemnisation of treaties, which

the unnamed pater patratus:

“ ... accomplishes ... with many words, expressed in a long metrical formula (carmen) that is not worth quoting. After reciting the terms [of the treaty] (legibus deinde recitatis), he cries:

‘Hear, Jupiter; hear, pater patratus of the Alban people: hear people of Alba: the Roman people will not be the first to depart from these terms, as they have been publicly rehearsed ... and clearly understood. If, by public decision, they should... [do so] with malice aforethought, then, on that day, may you, Jupiter, strike the Roman people as I shall now strike this pig: and may you strike with greater force, since your power and your strength are greater’”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 24: 6-8).

This oath would have followed a generalised fetial formula, adapted for ‘the present occasion’ by inserting the name of Alba as the counter-party. Livy then abruptly switched the narrative away from Rome, presumably to the site between Rome and Alba where the proxy battle was about to take place:

“When Spurius, [the Roman pater patratus], had [sworn the oath], he struck a pig with saxo silice (a flint stone). The Albans then pronounced their own metrical formulae and their own oath (sua item carmina ... suumque ius iurandum), by the mouth of their own dictator and priests”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 24: 9).

Livy had already named the Alban dictator as Mettius Fufetius.

Livy’s contention that the fetial rite for the solemnisation of treaties went back to the archaic period is reflected in etymological speculations published in the late Republic. For example, Varro, in a work published shortly before this part of Livy’s history, suggested that:

“Sus (pig) is derived from the Greek ὗς, while θὺς is derived (so they say) from the verb θύειν, that is to sacrifice. For the first rites of sacrifice seem to have derived from the sow, the traces of which are the following: ... in the rites that initiate peace, when a treaty is struck, a pig is killed (foedus cum feritur, porcus occiditur), ...”, (‘On Agriculture’, 2: 4: 9, translated by Bill Gladhill, referenced below, at p. 54).

A somewhat later entry in the lexicon of Flaccus apparently suggested that the word ‘foedus’ might have been derived from the form of this archaic ritual: the early part of Festus’ epitome is now lost but, according to Paul’s summary of it:

“Foedus [is] named, either:

✴from the fact that, in making peace, the victim is killed foede (shamefully, foully, hideously) ... ; or

✴because fides (good faith) is pledged in a foedus”, (‘De verborum significatu’, p. 74 L, translation from Bill Gladhill, referenced below, at p. 53).

Two other entries by Paul are also relevant to the present discussion:

✴Fetials: are so called from ‘faciendo’ (making), because the right of making war and peace lies with them”, (‘De verborum significatu’, p. 81L translation from Wilson Shearin, referenced below, at p. 84).

✴Feretrius: Jupiter is so-called from ‘ferendo’ (bringing), because he is thought to bring peace. From his temple, they take:

•the sceptre, by which they swear [an oath]; and

•the lapis silex [flint stone], by which foedus ferirent (they strike a treaty)”, (‘De verborum significatu’, p. 81L translation from Wilson Shearin, referenced below, at p. 84).

The first two of these entries, which are adjacent to each other in the manuscript, should be considered together, since the unspecified ‘they’ in the second entry were clearly the fetials discussed in the first. Thus, Flaccus apparently suggested that the temple of Jupiter Feretrius on the Capitol, which had traditionally been founded and dedicated by Romulus, had been so-named because this epithet meant ‘bringer of peace’. As we have seen, Varro had recorded that the fetials were still responsible for the solemnisation of treaties at his time of writing. Flaccus recorded that it housed the fetials’ flintstone and sceptre at his time of writing (which might have been after Octavian’s restoration of the old temple in 31 BC).

Flaccus/ Paul is our only surviving source for the existence of the fetials’ sceptre, which was presumably used (inter alia) for the swearing the oath of solemnisation of treaties. However, a possible reference to it the last book of Virgil’s ‘Aeneid’ (ca. 19 BC) suggests that it was perceived at this time as an object of great antiquity. The relevant passage describes a foedus made between Aeneas and his enemy, Turnus, prior to the duel that would decide which of them would succeed King Latinus: Bill Gladhill, referenced below, at p. 146) argued that:

“The ritual activity [used for this foedus] mirrors the [traditionally much later] fetial ritual as a kind of etiological backdrop.”

Importantly for this discussion, Latinus swore that he would honour the terms of the foedus, whichever man emerged victorious:

“May [Jupiter] Genitor, who sanctions treaties with his lightening, hear my words ! ... however things turn out, [nothing] shall break this peace and truce for Italy: nor shall any force change my mind, ... just as this sceptre (which, by chance, he held in his hand) shall never sprout, ... now that the craftsman’s hand has encased it in fine bronze and given it to the elders of Latium to bear”, (‘Aeneid’, 12: 206).

In his commentary on this passage, Servius explained that:

“The reason why the sceptre is [now] used when a treaty is made is as follows. The ancients always used a statue of Jupiter (simulacrum Iovis) [on such occasions], but this was difficult, especially when the treaty was made with a distant peoples. They discovered that they could effectively replace the image of Jupiter by holding the sceptre, which is [Jupiter’s], and his alone. Thus, when Latinus held the sceptre, it was not as king but [anachronistically] as pater patratus", (‘ad Aen’, 12: 206, my translation).

Servius clearly thought that Virgil had based his account of Latinus’ oath on the ritual that the pater patratus used when swearing on the part of the Roman people to honour a treaty, and, more specifically, that Virgil presented the sceptre of the Latin kings to his readers as a precursor of the sceptre that the fetials’ kept in the temple of Jupiter Feretrius. The entry by Flaccus/ Paul does not explicitly indicate when this practice of housing the sceptre and the stone in the temple had begun. Nevertheless, his account at least suggests that the fetials had chosen the temple as a home for the things that they used to the solemnisation of peace treaties because Jupiter Feretrius was the bringer of peace (and it is possible that this was more explicitly stated in Flaccus’ original). We therefore cannot rule out the existence of a Roman tradition that the fetials had housed the sceptre and stone in the temple since the first time that they had used them to solemnise a treaty: for example, Harriet Flower (referenced below, at p. 42) asserted that:

“[The] main purpose of the archaic temple of Jupiter Feretrius] is clear. It was closely associated with the rites of the fetials, and was used as a repository for their sacred objects. The cult title Feretrius seems to refer directly to the fetials and to their function of ratifying and regulating treaties.”

The foedus between Tullus and Mettius is obviously a matter of myth rather than history. However, we can compare Livy’s account of it with surviving evidence relating to Rome’s first treaty with Carthage. As James Richardson (referenced below, at p. 25) observed, this treaty is :

“One of the few documents from early Rome the authenticity of which no one now seriously doubts ... Polybius says that this treaty, and two others that were struck subsequently with the Carthaginians, were recorded on bronze tablets and were preserved in the treasury of the aediles.”

Polybius (2nd century BC) dated this first treaty to:

“... the consulship of Lucius Junius Brutus and Marcus Horatius, the first consuls after the expulsion of the kings [i.e., traditionally 509 BC] ...”, (‘Histories’, 3: 22: 1).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 256) observed that, although the historicity of Brutus is doubtful, the terms of the treaty, as Polybius transmitted them, accord well with our understanding of the political situation in the late 6th century BC. Polybius explained that:

“I give below as accurate a rendering as I can of [the inscribed text of this treaty], but ancient Latin differs so much from the modern that it can only be partially understood, even after much application by the most intelligent men”, (‘Histories’, 3: 22: 3).

Importantly, for our purposes, he recorded that:

“... the Carthaginians swore by their ancestral gods, [while] the Romans, following an old custom, swore by Jupiter Lapis ... The oath by Jupiter Lapis is as follows: the man who is swearing to the treaty takes a stone in his hand and, when he has sworn in the name of the State, says:

‘If I abide by this my oath may all good be mine, but if I do otherwise in thought or act, let all other men dwell safe in their own countries under their own laws and in possession of their own substance, temples, and tombs and let me alone be cast forth, even as this stone.’

So saying, he throws the stone from his hand”, (‘Histories’, 3: 25: 6-9).

John Rich (referenced below, 2011, at p. 194) observed that:

“... in respect of the ‘Jupiter stone’ oath, [Polybius] appears to be in error: [an oath sworn by Jupiter Lapis] is well attested elsewhere as an especially solemn oath, but it was always as taken by individual Romans, and it seems inappropriate for a treaty, since it binds only the swearer, not the Roman people.”

It is certainly true that the formula put forward by Livy (above) in the context of the Romans’ treaty with Alba would make much more sense:

“If, by public decision, [the Romans] should... [violate the treaty] with malice aforethought, then, on that day, may you, Jupiter, strike the Roman people as I shall now strike this pig: and may you strike with greater force, since your power and your strength are greater.”

If so, then:

✴the stone that had been recorded in the difficult archaic text on which Polybius relied might well have been the fetials’ lapis silex; and

✴his reference to Jupiter Lapis rather than simply to Jupiter might well have been a mistake on the part of ‘the most intelligent men’ who advised him on its meaning.

As Robert Ogilvie (referenced below, at p. 110) observed:

“It may, therefore, be that, in the middle of the [2nd century BC], the exact [fetial] formulae were not common knowledge, and that they had to be resuscitated by a later generation.”

Thus, as John Rich (referenced below, 2011, at p. 194) concluded from his analysis:

“... there is no reason to doubt that [this] fetial treaty ritual, performed with pig and flint stone, was of great antiquity, and [as other sources indicate, that it] was in regular (although perhaps not exclusive) use in the early and middle Republic for the solemnisation of treaties following authorisation by the Senate and people.”

This does not, of course, guarantee the authenticity of the ritual itself, as Livy described it, in which the fetial pater patratus:

✴recited a long carmen (which Livy chose not to quote);

✴proclaimed the terms of the treaty; and

✴swore an oath before sacrificing a pig by slashing its throat with a sacred flint stone.

Livy probably took most of this description from a relatively late antiquarian source (as discussed further below), in which the first line of the oath would have appeared in a generalised form, along the following lines:

“Hear, Jupiter; hear, pater patratus of the people of (here, he names whatever nation): hear people of (here, he again names whatever nation).

The annalistic source(s) that embedded this information in an account of the solemnisation of Tullus’ treaty with Mettius would have also (inter alia):

✴named Marcus Valerius as the verbenarius/ nuntius and described how he had made Spurius Fusius pater patratus by touching his head and hair with the verbenae;

✴presumably described their journey from Rome to the site chosen for the battle between the Horatii and the Curiati; and

✴suggested that the Albans had solemnised the treaty following their own custom.

Tullus’ War with the Latins

Livy recorded that, long before the birth of Romulus, Latinus Silvius, traditionally the fourth king of Alba, had:

“... founded several colonies, which he called the Prisci Latini”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 3: 7).

We hear little more about these Latin communities in the period in which Alba controlled them. However, according to Dionysius:

“It seems that, 15 years after [Tullus’] destruction of Alba, [he] sent embassies to the 30 cities that had been both colonies and subjects of Alba, demanding that they should [now] obey the orders of the Romans, who had succeeded to the Alban's supremacy over the Latin race ... The Latin cities did not answer these ambassadors individually. However, in a general assembly of the whole nation held at Ferentinum, they voted against accepting the sovereignty of the Romans ... This led to a war between the Romans and their kinsmen that lasted for 5 years ... [The warring parties] never engaged in pitched battles [during this time], ... but they made incursions into each other's territory ... None of the [usual] calamities of war were felt by either side. Accordingly, as the Romans were eager for peace, a treaty that left no rancour was readily concluded”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 34: 1-5).

Livy made no record of this war, but he did refer back to this treaty in his account of the reign of Ancus Marcius (see below). He also mentioned it again in the reign of Rome’s seventh and last king, L. Tarquinius Superbus (traditionally 534-509 BC), who:

“... had won great influence with the Latin nobles, when he gave notice that they should assemble on a certain day at the source of the Ferentina (ad lucum Ferentinae), saying that there were matters of common interest which he wished to discuss”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 50: 1).

This is the first of a number of references that Livy made to the lucus Ferentinae as the meeting place of the assembly of the Latin peoples: as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 233) pointed out, this would have been the place that Dionysius named as Ferentinum in the passage above. Livy then described an altercation between Tarquinius and Turnus Herdonius of Aricia, which led to the latter being condemned to death by drowning ad caput aquae Ferentinae (1: 51: 9). Tarquinius then argued before the assembly that:

“... it was in his power to proceed according to an ancient law (vetusto iure) since all the Latins, having sprung from Alba, were included in that treaty by which, from the time of Tullus, the whole Alban state, with its colonies, had come under Rome’s dominion. However, he suggested that the advantage of all would be better served if that treaty were renewed, and the Latins should share the good fortune of the Roman people, rather than if they were always to be dreading or enduring the razing of their cities and the devastation of their lands which they had suffered first in Ancus’ reign ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 52: 2-3).

Thus, it seems that, in Roman tradition, Tullus had struck a treaty with the Prisci Latini, and that, at least on some occasions, the latter conducted their relations with Rome through a collective assembly of some sort.

We can trace his tradition back to the antiquarian Lucius Cincius (ca. 100 BC): Flaccus (as summarised by Festus) recorded that, in his book on the power of the consuls, Cincius had observed that that:

“The Albans controlled affairs [in Latium] until the reign of Tullus. Then, after Alba was destroyed and until the consulship of P Decius Mus [i.e 340 BC], the [remaining] Latin peoples were accustomed to deliberate at the source of the Ferentina (ad caput Ferentinae), which is below the Alban Mount, and administered the command imperium [of their combined forces] by common counsel. Consequently, in a year in which, by order of the Latin nation, the Romans were required to send commanders to the army, several of our countrymen were accustomed to observe the auspices on the Capitol in the direction of the rising sun’’, (‘De verborum significatu’, p. 276 L, translated by Garry Forsythe, referenced below, at p. 188).

Pierre Sánchez (referenced below, at p. 11) observed that:

“Each of these two temporal indicators ... constitutes a dramatic turning point in the history of Romano-Latin relations in the annalistic tradition ... :

✴it was after Tullus’ destruction of Alba Longa that the Romans first attempted to establish their hegemony over the Latins; and

✴it was in the consulate of P. Decius Mus that the Latins finally submitted to Rome and were, for the most part, incorporated into the civitas Romana”, (my translation).

In other words, Cincius recorded a tradition in which Tullus’ attempt to assert Roman hegemony in Latium after his destruction of Alba marked the start of a process that continued until 340 BC, when Decius famously gave his life to the gods in return for the Romans’ decisive victory over the Latins at the Veseris, at which point the Latin federation came to an end.

We should now look yet again at Cicero’s record that Tullus:

“... established the rule by which wars were declared (ius quo bella indicerentur) which, once he himself had created it most justly, he sanctioned by the fetial rites (sanxit fetiali religione), so that all war that had not been announced and declared (denuntiatum indictumque) was judged to be unjust and impious”, (‘On the Republic’, 2: 31, based on the translation by Hannah Cornwell, 2014, referenced below, at p. 41, note 2).

As we have seen, John Rich (referenced below, 2011, at p. 212) argued that:

“Cicero must have had some authority for associating:

✴the tale of how Tullus’ war with Alba began; with

✴the introduction of the fetial ius [for the preliminaries of war];

and this may well have been how the early Roman historians portrayed it.”

I argued above that this hypothesis is potentially undermined by the fact that none of Diodorus (as far as we know), Livy and Dionysius made this association. Indeed, Livy and Dionysius assumed that Tullus declared war on Alba under the terms of an existing treaty between them. According to Dionysius, this treaty:

“... had been made in the reign of Romulus, [and] stipulated, among other things, that neither of them should begin a war: if either complained of any injury whatsoever inflicted upon them by the other, that city would demand satisfaction ... and, if it failed to obtain it, then the treaty would be considered as already broken, and the offended city could then make war as a matter of necessity”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 3: 1).

This was presumably why Tullus had to go to such lengths to ensure that it was Cluilius who broke the treaty, thereby attracting the anger and vengeance of the gods by whom it had been sworn. This led to two new treaties:

✴the one between Tullus and Mettius, which Livy recorded as the first to be solemnised by the fetial ritual, and which ended with the destruction of Alba; and

✴20 years later (according to Dionysius), this new treaty between Tullus and the Latins.

It is possible that:

✴this last treaty had traditionally contained, as one of its provisions, the ius quo bella indicerentur in the form described by Cicero (which would have reflected a similar condition in the original treaty between Alba and Rome); and

✴Cicero’s source had recorded that (pace Livy) this was the first treaty to be solemnised by the fetial ritual.

Fetials in the Reign of Ancus Marcius

Livy continued his account of the fetials in the Regal period by describing a significant addition to their responsibilities in the reign of Rome’s fourth king, Ancus Marcius (traditionally 672-616 BC). This occurred in the context of an outbreak of hostilities with the Prisci Latini (ancient Latins).

According to Cicero, Tullus was succeeded by:

“... Ancus Martius, grandson of Numa Pompilius through his daughter ... After conquering the Latins in war, he incorporated them in the Roman State. He also added the Aventine and Caelian Hills to the city, divided the territory he had conquered among the citizens, declared all the forests along the [Tyrrhenian] coast that he had obtained by conquest to be private property, and built a city [later Ostia] at the mouth of the Tiber, which he settled with colonists. And so, after a reign of 23 years, he died ”, (‘On the Republic’, 2: 33).

Dionysius made only one mention of the Prisci Latini:

“Soon after [Aeneas and his followers settled at Lavinium], they changed their ancient name and, together with the Aborigines, were called Latins, after the king of that country. And leaving, Lavinium, they joined with the inhabitants of those parts in building a larger city, surrounded by a wall, which they called Alba; and setting out thence, they built many other cities, the cities of the so‑called Prisci Latini, of which the greatest part were inhabited even to my day”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 45: 1-2).

Festus

“Fabius Pictor says that Puilia Saxa is located at a landing spot along the Tiber. Labeo believes this is the name of spot where Ficana stood, at the eleventh milestone of the Via Ostiensis’’, (‘De verborum significatu’, p. 298 L, translated by Ross Holloway (referenced beloww, at p.

Ancus’ War with the Prisci Latini

As noted above, Livy recorded that, early in Ancus’ reign:

“The Latins, with whom a treaty had been made in the time of Tullus, plucked up the courage to raid Roman territory, ...)”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 32: 3).

When Ancus claimed restitution, presumably under the terms of this treaty, following the Latin raids on his territory, they:

“... returned an arrogant answer, convinced that the [new] Roman king would spend his reign in inactivity amid shrines and altars. But ... Ancus ... honoured the memory of [the warlike] Romulus as well as [the peace-loving] Numa ... [Furthermore, he understood] that the times were better suited to the rule of a king like Tullus than one like Numa. Therefore, just as Numa had instituted religious observances in peacetime, he would [now] establish ceremonies of war: in order that they should be not only waged but also declared by some ritual, Ancus introduced from the ancient people of the Aequicoli the rule (ius) that the fetials now have, by which restitution is sought (quo res repetuntur)”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 32: 5).

He then embarked on a detailed description of the ritual prescribed by this ius fetiale (discussed in the next section). He ended with the emphatic observation that:

“This is the manner in which, at [the time of Ancus], redress was sought from the Latins and war was declared on them (ab Latinis repetitae res ac bellum indictum), and the custom has been received by posterity”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 32: 14).

However, he did not describe an actual war with the Prisci Latini at any point in Ancus’ reign: instead, he recorded a series of engagements with individual Latin communities, starting with the fact that:

“Ancus delegated the care of the sacrifices to the flamines and other priests and ... proceeded to Politorium, one of the Latin cities. He took this place by storm and ... transferred the whole population to Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 33: 1-2).

As we have seen, Cicero had recorded that Tullus had devised the ius fetiale for the preliminaries of war: all he recorded of the reign of Ancus was that:

“After conquering the Latins in war, he incorporated them in the Roman State; he also added the Aventine and Caelian Hills to the city, divided among the citizens the territory he had conquered, made all the forests along the coast, which he had obtained by conquest, public property, built a city [later Ostia] at the mouth of the Tiber and settled it with colonists. And so, after a reign of 23 years, he died”, (‘On the Republic’, 2: 33).

Livy then embarked on a long and generalised description of the fetial rituals that were presumably prescribed in the new ius fetiale for:

demanding restitution (as described above); and

declaring war (see below).

However, he never actually described a war between Roma and the Prisci Latini collectively during Ancus’ reign.

Livy clearly drew on a number of sources in this section. John Rich (referenced below, 2011, at p. 202) argued that:

“The original elements will have comprised separate accounts of:

✴a process for demanding restitution; and

✴a spear rite for initiating war.

A subsequent writer will then have brought the two elements together, composing the account of the Senate’s vote for war as a link. Livy could have found the combined account in an earlier writer, but it is simpler to suppose that he himself made the combination.”

I discuss these two elements in successive sections below.

Fetial Ritual for Demanding Restitution (1: 32: 5-10)

As we have seen, Livy followed a tradition in which Ancus Marcius (Tullus’ successor), when he was faced with a series of raids on his territory by the Prisci Latini, copied from the Aequicoli:

“...the rule (ius) that the fetials now have, by which restitution is sought (quo res repetuntur)”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 32: 5).

Livy presumably found this information in an annalistic source. He then embarked on a long and generalised description of the fetial rituals that were presumably prescribed in the new ius fetiale for:

✴demanding restitution (as described in this section); and

✴declaring war (see below).

In the ritual for demanding restitution, as Livy described it, the fetial who was appointed to represent the Romans on occasions such as this made two visits to the offending community:

✴On the first visit:

“When the legatus comes to the borders of those from whom restitution is sought (res repetuntur), with his head covered with a fillet (the covering is of wool), he says:

‘Hear, Jupiter; hear, borders (here he names the nation [to which the offenders] belong); hear divine law (fas). I am the public messenger of the Roman people (publicus nuntius populi Romani). I come justly and righteously (iuste pieque) as an ambassador (legatus), and let there be faith (fides) in my words.’

Next he recites the [Roman] demands, after which, he calls Jupiter to witness:

‘If I unjustly and unrighteously (iniuste impieque) demand that those men and those goods (illos homines illasque res) be handed over to me, then may I never [again] be allowed to enjoy my fatherland.’

He recites these words, altering only a few of those in the invocation and the oath:

•when he crosses the borders;

•again to the first man he encounters;

•again when he enters the gate of the town; and

•again when he has entered the forum”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 32: 6-8, translated by John Rich, 2011, at p. 200).

✴On the second visit, he received the reply from the offending community and:

“If those whom he demands are not handed over at the end of 33 days (these are the customary number), he declares war thus (bellum ita indicit):

‘Hear, Jupiter, and thou, Janus Quirinus, and, all ye heavenly and terrestrial and infernal gods, hear! I call thee to witness that that people (here he names whichever it is) is unjust (iniustum esse) and has not made just return”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 32: 9-10, translated by John Rich, 2011, at p. 200).

We might expect that, in the last line of the proclamation above, the nuntius would actually declare war. However, it ends with something of a whimper: having called on the gods to witness that the unnamed offending community has refused the Romans’ just demands, the legate simply says that:

“... we shall consult the elders in our fatherland, by what means we may obtain our due”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 32: 9-10, translated by John Rich, 2011, at p. 200).

The account above includes four fetial formulae:

✴on his first visit (on four separate occasions on his walk from the border to the forum) the legatus is required to:

•swear in the prescribed manner that he had been legitimately appointed as the publicus nuntius populi Romani;

•recite the terms of the Roman demands for restitution by means of the surrender of both offenders and plunder; and

•swear in the prescribed manner that, if these demands were unjust, he would forfeit his Roman citizenship; and

✴on his second visit, 33 days later, if the Romans’ demands are refused, he is required to call on the gods to witness the unjust response and, probably in the original, to declare war.

It seems to me that these formulae probably came from a single antiquarian source, and that Livy embedded in a narrative (possibly of his own composition) that added:

•the choreography of his first visit;

•the allegedly ‘customary’ 33 days that elapsed before he returned; and

•the last line of the fourth formula, which, in the original source, probably articulated a declaration of war.

Fetial Spear Ritual (1: 32: 10-14)

After his second visit, if the Roman demands were denied, the nuntius:

“... returns to Rome to consult. Straightaway, the king would consult the senators in roughly these words, addressing the man whose opinion he customarily asked first:

‘Having regard to those goods, disputes and causes (rerum litium causarum) of which the pater patratus of the Roman people of the Quirites gave notice (condixit) to the pater patratus of the Prisci Latini and the men of the Prisci Latini, which goods they have not given, rendered or discharged (res nec dederunt nec solverunt nec fecerunt) as they should have been given, discharged and rendered, speak: how do you vote?’

Then, [the first senator] would reply:

‘I vote that the goods should be sought in a pure and righteous war (puro pioque duello), and thus I agree and decree.’

Then the rest would be asked their opinion in order and, when the majority of those present should vote for the same opinion, the war had been agreed.”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 32: 10-12, translated by John Rich, referenced below, 2011, at pp. 200-1).

As John Rich (at p. 202, quoted above) suggested, this linking passage might well be Livy’s free composition.

Livy then described the ritual by which this decision was put into effect:

“The customary practice was for a fetial to carry a bloody spear, tipped with iron or hardened in fire, to their borders and, with not less than three adults present, to say:

‘Since:

✴the peoples of the Prisci Latini and the men of the Prisci Latini have acted and offended against the Roman people of the Quirites;

✴the Roman people of the Quirites has ordered there to be war against the Prisci Latini;

✴and the Senate of the Roman people of the Quirites has voted, agreed and decreed (censuit consensit consciuit) that war should be made against the Prisci Latini;

... I and the Roman people declare and make war (ego populusque Romanus … bellum indico facioque) against the peoples of the Prisci Latini and the men of the Prisci Latini.’

When he had said this, he would hurl the spear across their borders”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 32: 12-14, translated by John Rich, referenced below, 2011, at pp. 200-1).

Livy is not the earliest of our surviving sources for the archaic spear rite for the declaration of war: it was recorded in a fragment of a now-lost part of the work of Diodorus Siculus (above), which is known from a work of the Byzantine John Tzetzes (12th century AD):

“The Roman and Latin nations would never march to a war undeclared. Rather, they would throw a spear before the foreign land as an open declaration of their enmity. Only then would the war begin against that foreign nation. That is what is said by Diodorus and everyone [else] writing about Latin affairs”, (‘Chiliades’, 5: 555-61, reproduced as ‘’Library of History’, presumed fragment 8: 26).

This fragment is usually assumed to follow a longer fragment that describes the preliminaries of the war between Tullus and Cluilius, ruler of Alba (see below). and it might have been a preface to the start of these hostilities.

Diodorus made no reference to any fetial involvement in this rite, at least as far as we know. However, Aulus Gellius (2nd century AD) recorded that:

“Cincius writes in the third book of his ‘De Re Militari’ that the fetial of the Roman people (fetialis Romani populi), when he declared war on the enemy and hurled a spear into their territory, used the following words:

‘Since:

✴the Hermundulan people and the men of the Hermundulan people have made war against the Roman people and have transgressed against them; and