Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Cult of Vediovis

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Cult of Vediovis

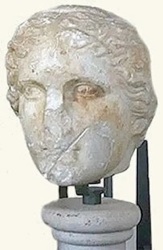

Marble statue of Vediovis (ca. 80 AD) from his temple on the Capitol (now in the Musei Capitolini)

From Dr Erin Warford (referenced below)

Cult of Vediovis at Rome

According to Varrro:

“... the ‘Annals’ record that, [after Romulus and the Sabine king Titus Tatius had agreed to share power in the newly-founded city], Tatius vowed arae (altars) to ... [a number of Sabine deities, including] Vediovis ...”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 5: 74, translated by Roland Kent, at p. 71).

However, as Stefan Weinstock (referenced below, at p. 8) observed, material evidence of the cult of Vediovis:

“... appeared relatively late in Rome: [the earliest surviving evidence relates to the] two temples [that] were built for him at the beginning of the 2nd century BC:

✴one on the Tiber island, which was dedicated on 1st January, 194 BC; and

✴the other on the Capitol, which was dedicated on 7th March, 192 BC.

... This evidence is reliable, but does not reveal more than that Vediovis was considered to be an indigenous god [by this time, who could therefore] receive a temple inside the pomerium.”

Each of these temples was vowed in battle by the same person, L. Furius Purpurio (cos 196 BC);

✴As a praetor in 200 BC, and in the absence of the commanding consul, he led what was, in effect, a consular army to relieve Cremona, which was besieged by Gauls. According to Livy, at a crucial moment in the ensuing battle, he:

“... vowed a temple to Deoiove (sic), should he rout the enemy on that day”, (‘History of Rome’, 31: 21: 12).

He achieved a stunning victory and was awarded a controversial triumph (since he was only a praetor and had allegedly acted against the orders of the commanding consul). The temple that he vowed on this occasion was the temple of Vediovis on the Tiber Island.

✴As consul in 196 BC, Furius and his consular colleague, M. Claudius Marcellus, were both assigned to Cisalpine Gaul. While Claudius was awarded a triumph at the end of the year, it seems that Furius was denied one. However, Livy recorded that:

“Two temples to Iove (sic), were dedicated on the Capitol [in 192 BC]; L. Furius Purpurio had vowed [both of them]:

✴one while praetor [in 200 BC], in the Gallic war; and

✴the other while consul [in 196 BC]”, (‘History of Rome’, 35: 41: 8).

The first of these temples is usually considered to be Furius’ earlier temple, which was actually on the Tiber Island. The second, which Furius must have vowed during a battle in Gaul, was actually the temple of Vediovis on Capitol.

Unfortunately, it seems that modern scholarship is unable to explain why Furius should have chosen Vediovis for the temples that he apparently vowed in battle in 200 and 196 BC respectively.

As we shall see, there is evidence for the cult of Vediovis and Latium and Etruria, but this adds little to our understanding of his cult. This leaves us asking, with Howard Scullard (referenced below, at p. 56):

“... who was Vediovis ?

As he pointed out, all we know of the origins of this god comes from the etymology of his name, which:

“... appears with the same variations as Iovis , [but] with the particle ‘ve-’ prefixed ... The meaning of ‘ve-’ is ambiguous because it can be either

✴privative [i.e., it can mean ‘not Jove]; or

✴diminutive [i.e., it can mean ‘young Jove’].”

The earliest surviving etymology was that given by the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus (as epitomised by Paul the Deacon) in relation to the adjective ‘vesculi’:

“The prefix ‘ve-’ signifies small, and Vediovem parvum lovem (Vediovis signifies the young Jove)”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 519 L, my translation).

However, as Cicero (ca. 45 BC) warned, reliance on etymology in order to discern divine origins is:

“... a dangerous practice: [anyone doing so] will be in difficulties with a great many names. [For example], what will [he] make of Vediovis ... ?”, (‘Nature of the Gods’, 3: 62, translated by Harris Rackham, referenced below).

Fortunately, there is material evidence available to us, albeit that it is not easily interpreted. I do my best in the sections below.

Cult Statues from the Temple of Vediovis on the Capitol

Much of what we know about the Roman cult of Vediovis is derived from literary records of the first cult statue in his temple of the Capitol and the evidence of its replacement (which survives and is illustrated above).

Cypress Statue of ca. 192 BC ?

Pliny the Elder (ca. 79 AD), in a passage that dealt with the durability of various kinds of wood, observed that:

“Cypress ... is the wood that, beyond all others, retains its polish in the best condition for all time. Has not the cult statue of Vediovis on the Arx (simulacrum Vediovis in arce) ... , [which is] made of cypress, lasted since its dedication in the 561st year after the foundation of Rome (a condita urbe DLXI)”, (‘Natural History’, 16: 79).

If Pliny was using Varronian dating, this would mean that the cult image in the temple of Vediovis on the Capitol had been consecrated in 193/2 BC. However, as John Briscoe (referenced below, at p. 114) pointed out, we have no idea what precise dating system that Pliny’s source had used and, in any case:

“... it could be that the numeral in [the surviving manuscripts] is corrupt, and that it should read 562. It is perfectly possible that the temple and the statue were dedicated on the same day [on 7th March 192 BC] ... ”

The important point is that the original cypress statue of Vediovis in his temple on the Capitol apparently survived in Pliny’s lifetime.

Ovid (8 AD) seems to have used the evidence of this statue to explain the nature of Vediovis to the readers of his Fasti:

“He is the young Jupiter: look on his youthful face; look then on his hand, [which] holds no thunderbolt:

✴Jupiter assumed the thunderbolt [only] after the giants dared attempt to win the sky; at first he was unarmed. ...

✴A she-goat [Amalthiea] also stands [beside his image]; the Cretan nymphs are said to have fed the god; it was the she-goat that gave her milk to the infant Jove”, (‘Fasti’, 3: 429-48, based on the translation of James Frazer, referenced below, at p. 153).

Stefan Weinstock (referenced below, at p. 9) suggested that Ovid characterised Vediovis as the ‘the young Jupiter’ on the authority of Verrius Flaccus (above). It seems to me that this was indeed his starting point, and that the therefore:

✴interpreted the presence of the goat as an allusion to the nursing of the young god on Mount Ida; and

✴(probably) invented the story of Jupiter’s assumption of the thunderbolt only after the emergence of the threat from the giants in order to account for the absence of thunderbolt (the traditional attribute of Jupiter).

However, as discussed below, it is entirely possible that the original cypress statue had included a thunderbolt in the hand of the god, but that this attribute had disappeared by Ovid’s time.

Marble Statue of ca. 81 AD ?

It seems that the cypress statue described above was destroyed by fire soon after Pliny’s death in 79 AD: as Christer Henriksén (referenced below, at p. 410) observed, the Emperor Domitian (81-96 AD) rebuilt a number of temples on the Capitol:

“... the temples of Iuppiter Tonans and Vediovis ([which had presumably been] damaged in the fire of 80 AD); the temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus (which had been rebuilt by Vespasian .. in 69 AD but had burned down again in 80 AD); and probably also the temple of Juno Moneta on the Arx.”

Howard Scullard (referenced below, at p. 57) noted that:

“During excavations of this temple in 1939, a marble statue [illustrated at the top of the page] was found: a male figure of Apolline type, with a cloak hanging over the left arm, although the arms and head were missing. This must have replaced the earlier wooden statue, which may have been destroyed in the fire of 80 AD.”

Aulus Gellius (ca. 170 AD) presumably described the replacement statue (or a later copy of it) in the following passage:

“The statue of the god Vediovis, which is in [his] temple [on the Capitol], ... holds arrows, which, as everyone knows, are devised to inflict harm. For that reason it has often been said that that god is [a form of] Apollo; and a she-goat is sacrificed to him ‘in humano ritu’ [by a human rite, whatever that means] and a representation of that animal stands near his statue”, (‘Attic Nights’, 5: 12: 11-12).

It seems to me that Gellius’ identification of this as a statue of Apollo probably arose from the fact that representations of an clean-shaven, almost-naked Jupiter were uncommon. Howard Scullard (referenced below, at p. 58) observed that:

“Gellius may have deduced the sacrifice of a goat [to Apollo] from the animal accompanying the statue: [however, there is no other evidence for this and the presence of] an attribute [of this kind in a statue] does not necessarily involve it being an object of sacrifice.”

More importantly, if, by Gellius’ time, the statue was taken as a representation of Apollo, the the attribute in the hand of the god would have been ‘read’ as a bunch arrows rather than as a thunderbolt.

Cult Statues from the Temple of Vediovis on the Capitol: Conclusion

The difficult question of what, if anything, Vediovis held in his hand in either of his cult statues is important for the understanding of his cult. As discussed above, it is at least possible that, in both statues, he originally held a thunderbolt:

✴those of the cypress statue could have been lost by the time of Ovid; and

✴those of the later statue could have easily been mistaken for arrows.

Furthermore, even if Vediovis was thought to be a form of Apollo by the time of Gellius, we have no reason to doubt the testimony of both Verrius Flaccus and Ovid that Vediovis was regarded as the young Jupiter in the Augustan period, particularly since we have earlier evidence for the worship of the young Jupiter in Latium: according to Cicero (ca. 44 BC), a statue at the sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia at Praeneste depicted:

“... the infant Jupiter (Iove puer), who is represented as sitting with Juno in the lap of Fortuna and reaching for her breast, ... [which] is held in the highest reverence by mothers”, (‘On Divination’, 2: 85, translated by William Falconer, at p. 467).

In the section below, I hope to show that surviving numismatic evidence can be used in support of this hypothesis.

Denarius of L. Caesius

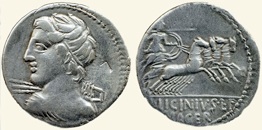

Denarius issued by L. Caesius: 112-1 BC (RRC 298/1)

Obverse: Young god holding a thunderbolt: monogram behind the god read as A͡P (see below)

Reverse: Lares (identified by ’L͡A R͡E’, with dog between; bust of Vulcan above; ‘L. CAESI’ below

It is possible that the silver denarii (RRC 298/1) that were issued by L. Caesius in 112 or 111 BC might throw some light on the present discussion, since the obverse depicts the head and shoulders of a young god who, like the figure in the surviving cult statue of Vediovis (above), is naked apart from the cloak hanging from his left shoulder. However, in this case, he clearly holds a thunderbolt (as evidenced by its zig-zag shafts), which suggests the young Jupiter. However, there is nothing on the coins that explicitly confirms his identity, so we need to look in some detail what is known about their issuer and, in particular, what he might have wanted to convey by the iconography that he chose for them.

L. Caesius, Moneyer of 111/2 BC

According to Peter Wiseman referenced below, 1971, at p. 219 , the moneyer L. Caesius was a ‘new man’ in Rome. Gary Farney (referenced below, at p. 257) pointed out that he was:

“... the first Caesius known to have held any political post at Rome”;

and suggested that he might be the L(ucio) Caesio C(ai) f(ilio) imperatore who was recorded in an inscription (AE 1984, 495) from Alcántara as having taken the surrender of a local tribe as praetorian commander in Hispania Ulterior in 104 BC (see T. Corey Brennan, referenced below, at p. 499). Farney also pointed out (at p. 258) that:

“Several Caesii are known to have held high office early at Praeneste, and they maintained a connection to the town into the 2nd century AD.”

According to Edward Bispham (referenced below, at p. 463 and p. 467, note 33), Praeneste probably retained its own citizenship until the time of its colonisation by Sulla in 80 BC. However, L. Caesius was clearly a Roman citizen by 112 BC: it is therefore possible that he or his father had received civitas per magistratum after holding office at Praeneste, since the measure that extended Roman citizenship to Latins who had held office in their own cities seems to have been enacted in ca. 122 BC (see, for example, Christopher Dart, referenced below, at p. 61 and Saski Roselaar, referenced below, at p. 219).

As Elizabeth Palazzolo (referenced below, at p. 209) observed, Caesius’ putative status as a ‘new man’:

“... makes these coins particularly interesting: without a respectable family history at Rome to reference, he chooses instead to draw legitimacy from his extended family connection to Praeneste.”

It seems that his denarii were successful in helping him launch his political career in Rome, since he had achieved praetorian imperium by 104 BC. We might therefore be able to deduce the identity of the young god on the obverse on the basis of the part it would have played in introducing a new man from Praeneste so successfully to the Roman electorate.

Iconography of the Obverse of Caesius’ Denarii

Obverse of RRC 298/1 (112-1 BC)

Obverse of RRC 297/1 (112-1 BC) Obverse of RRC 354/1 (84 BC)

The stunning portrait of the young god on the obverse of Caesius’ denarii stands out among the series of mostly helmeted gods on the obverses of the 34 denarii that were minted in the decades to either side of it (as can be seen in this extract from the on-line database of the American Numismatic Society): the only other image that comes close in terms of its innovation, artistry and individuality is that of Hercules on the obverse the denarii (RRC 297/1) of Caesius’ triumviral colleague, the now-unknown “Ti. Q” (illustrated above). Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at pp. 311-2) suggested that the latter image represented Hercules Respiciens (Hercules Looking Backwards), and it is possible that the pose of the god on Caesius’ coin owes much to this ‘backward-looking’ composition. However, the portrayal of Hercules is essentially static, as would have been expected of an obverse design at this time. The thing that really stands out about the portrayal of the young god on the obverse of Caesius’ denarii is its dynamism: the depiction of his tensed, powerful shoulder muscles and the fact that his right shoulder is lower than his left brilliantly conveys the impression that he is about to hurl the thunderbolt that he holds in his right hand. (I discuss the later copy copy of Caesius’ young god on the obverse of RRC 354/1 below: I have illustrated it here to underline the dynamism of the original.)

It seems to me that Caesius must have put a great deal of thought into this composition, presumably because he was keen to maximise the impact that it would have on his Roman ‘audience’. This raises two related question:

✴which Roman deity did Caesius choose to portray on the obverse of his denarii; and

✴what would this representation of him conveyed to Caesius’ Roman audience.

RRC 298/1 (112-1 BC) RRC 294/1 (113-2 BC) RRC 340/1 (90 BC) RRC 353 (85 BC)

L. Caesius T. Didius L. Calpurnius Piso Frugi Mn Fonteius

Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at p. 312) argued that the monogram behind the head of the young god on the obverse of Caesius’ denarii, which he read as A͡P, should be read as Apollo, but:

“... since the object in his hand is clearly a thunderbolt, the type [of the deity] perhaps results from the assimilation of Apollo with Jupiter ...”

Crawford considered, but rejected, the alternative hypothesis that this deity resulted from the assimilation of Apollo with Vediovis, citing the testimony of Ovid (above) that the cypress image of Vediovis in his temple on the Capitol depicted him before he had assumed the thunderbolt. James Luce (referenced below, at p. 25), in his analysis of the three later coins including RRC 353/1 (discussed below, with tits monogram illustrated above) also argued that:

“... the [alternative] identification [of this deity] with Vediovis cannot stand. ... The evidence of Ovid ... rules this out absolutely.”

However, Peter Wiseman (referenced below, 2009, at p. 76) argued that there was no basis for privileging Ovid’s evidence for the absence of a thunderbolt in the Augustan period (since, for example, it might simply have been lost by his time). However, like Crawford and Luce, he asserted (at p. 73) that the monogram:

“... ought to mean AP(ollo), the identification [perhaps] made necessary by the unfamiliar attribute [of the thunderbolt rather than the usual arrows].”

Wiseman therefore concluded that:

“The most economical explanation ... is that [Caesius] accepted the identification of Vediovis as Apollo, and of his weapon as a thunderbolt.”

In summary, Crawford, Luce and Wiseman all believed that the monogram indicated that the young god on the coin represented the assimilation of Apollo [minus his arrows] with Jupiter and his thunderbolt, albeit that:

✴Crawford and Luce privileged Ovid’s testimony relating to the empty hands of the statue in the temple on the Capitol, and this precluded his identification as Vediovis; while

✴Wiseman discounted Ovid’s testimony in this respect, and therefore suggested that the young god was Vediovis, a form of Apollo whose attributes was a thunderbolt rater than a sheaf of arrows.

However, as Tyler Holman (referenced below, at p. 99) pointed out, as early as 1895, Leopold Montague (referenced below, at p. 163) suggested that this monogram and the similar one on the obverse of RRC 353/1 (issued by Mn Fonteius, discussed below, with its monogram illustrated above):

“... might instead be taken as representing RMA, signifying ROMA. Montague made a strong case for this reading by pointing out that the forked crossbar was rarely seen in the letter A by this time, and that, in the case of L. Caesius, the letter [A] appears with a straight crossbar on the reverse of the same coin. He therefore interpreted [the forked crossbar of the monogram as belonging to] the letter M. He drew further attention to the similarity of [this] monogram with [another] that appears on the denarii of L. Piso Frugi, [where it unambiguously represents] ROMA ... This case is strengthened by the fact that the monogram [R͡͡M͡A] is ... replaced by the complete word ROMA on a variant of this issue.”

We might add that the monogram that appears on the obverse of two of the denarii issued in 113-2 BC is arguably an expanded version of that used on the denarii of Caesius and Fonteius: this earlier monogram is behind the head of:

Perhaps the most important point to make in this context is that the inscription ROMA is overwhelmingly the most common inscription on Roman Republican coins (see for example the catalogue of these inscriptions complied by Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at pp. 879-89), and it sometimes appears on coins on which the goddess herself is not depicted (see, for example the denarii RRC 340/1 and RRC 293/1 discussed in this section). It therefore seems to me that we must assume that the monogram on the obverses of the denarii of both Caesius and Fonteius should be read as R͡͡M͡A=ROMA, and that it has no direct bearing on the identity of the young god depicted in front of it.

On the basis of this analysis of the obverse of Caesius denarii in isolation, we can make little headway in answering the two questions above: all we can really say is that he chose a particularly arresting portrayal of of a young god who was naked apart from a cape over his left shoulder and about to hurl a thunderbolt. However, if we:

✴accept that the accompanying monogram would have had no direct bearing on his identity; and

✴assume that the cypress statue of Vediovis on the Capitol (and perhaps that of the Temple on the Tiber Island):

•was dressed like the marble statue that replaced it; and

•originally held a thunderbolt;

then we might reasonably assume that a Roman looking at this image in 112-1 BC would have identified this deity as Vediovis, and characterised him as the young Jupiter. That, of course, still begs the following questions:

✴why Caesius chose Vediovis for the obverse of his denarii?; and

✴what message his choice would have conveyed to his Roman audience?

It is now time to look at the reverse iconography to see if we can throw further light on the matter.

Iconography of the Reverse of Caesius’ Denarii

Reverse of RRC 298/1 (with monograms picked out)

As noted above, the reverse of Caesius’ denarii depicted:

✴a pair of lares (identified by ’L͡A R͡E’, with dog between them; and

✴a bust of Vulcan, identified by the blacksmith’s tongs over shoulder, above.

Caesius’ background easily explains the presence of Vulcan, since, by his time, Vulcan was firmly associated with the foundation legend of Praeneste. For example, according to the commentary on a passage by Virgil (‘Aeneid’, 7: 676-81) by the so-called Verona Scholiast:

“Cato, in the ‘Origines’ [ca. 150 BC], says that young girls found [a baby] in the hearth and, for that reason, considered him to be the son of Vulcan ... [They] called him Caeculus because of his tiny eyes. It was [Caeculus] who, with a haphazard collection of shepherds, founded Praeneste”, (translated by Timothy Cornell, in T. J. Cornell (editor), referenced below, at Vol. II, p. 197), my changed word order).

Matters are not so quite so straightforward when we come to the lares, although, as Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at p. 312) pointed out, the following passage by Ovid enables us to identify them more precisely: Ovid recorded that the 1st May:

“... saw an altar and small images set up [in Rome] in honour of the Lares Praestites. They had been vowed by that man from Cures (voverat illa quidem Curius), but the passage of time destroyed many things; long old age even hurt stone. The reason for their epithet is that they stand guard (praestant) over everything under their gaze. They also stand before us, and they are in charge of the city walls (praesunt moenibus Urbis), and they are present (sunt praesentes) and bring help. A dog, carved from the same stone, used to stand at their feet, Why did it stand there with the Lares? ... [Because], like the Lares, dogs are watchful (pervigilantque Lares pervigilantque canes)”, (‘Fasti’, 5: 129-144, based on the translation by Harriet Flower, referenced below, at pp. 108-9).

Crawford therefore concluded that the two figures were the Lares Praestite and that:

“... the monograms [L͡A R͡E on the reverse] should be resolved as LA[RES] PR[A]E[STITES].”

(Even if, as I suggest on the illustration above, the monograms indicate only that these are lares, the presence of the dog between them would identify them as Lares Praestites).

Caesius choice of them for the reverse of his denarii was quite extraordinary, since they are not found on any other coin in the catalogue of the known coins of the Roman Republic. The most obvious explanation is that he made it simply on etymological grounds: according to the Virgilian commentary of Servius Danielis:

“Cato says: Praeneste was given its name because it stands out in the mountains (montibus praestet)”, (‘ad Aen’, 7: 682, translated by Timothy Cornell, in T. J. Cornell (editor), referenced below, at Vol. II, pp. 198-9, my changed word order).

In other words, it is possible that Caesius chose them because his Roman audience (or, at least, those Romans who were familiar with works such as Cato’s ‘Origines’) would recognise:

✴Vulcan as the founder of Praeneste; and

✴the Lares Praestites as the ‘Lares of Praeneste’.

I do not wish to discount here the more sophisticated suggestion by Gary Farney (referenced below, at pp. 257-8) followed by Elizabeth Palazzolo (referenced below, at p. 209 ) that:

✴the gens Caesia claimed descent from Caeculus; and

✴the Lares Praestites featured in the foundation myth of Praeneste as the ‘divine uncles’ of Caeculus (since later versions of the foundation myth identify Caeculus’ mother as the sister of two brothers known as the divi fratres, Depidii or Digidii.

However, for our purposes, it is enough to establish that, for whatever reason, Caesius almost certainly combined Vulcan and the Lares Praestites on the reverse of his denarii in order to draw attention to his Praenestine heritage.

‘Reading’ the Iconography of Caesius’ Denarii

In her commentary on the iconography of the reverse of Caesius’ denarii, Elizabeth Palazzolo (referenced below, at p. 209), argued that, as a ‘new man’:

“... without a respectable family history at Rome to reference, he chooses instead to draw legitimacy from his extended family connection to Praeneste.”

While this is surely correct, I think that we can expand on it in relation to an observation by Cicero, who was himself a ‘new man’, in his case, from Arpinum. The relevant remark comes in answer to a question, posed by his friend, Atticus, as to whether the patria (fatherland) of Cato (yet another ‘new man’) was Rome or his native Tusculum:

“I believe that [Cato] and all the residents of the municipia have two fatherlands: one by nature, the other by citizenship. Cato, although he was born in Tusculum, was admitted into the polity of the Roman people. [Therefore]:

✴while he was a Tusculan by birth, he was a Roman by citizenship; and

✴he had one fatherland by place, the other by law ...”, (‘On the Law’, 2:5, translated by Elizabeth Palazzolo, referenced below, at p. 34).

Cicero was writing after the Social Wars (91-88 BC), and had thus been born a Roman citizen. On the other hand, (as discussed above), Caesius might well have been a citizen of Praeneste until shortly before minting his coins. We might therefore usefully consider how he might have regarded his two fatherlands, particularly since there had been conflict between them in the recent past.

We might usefully begin in 216 BC, immediately after the Romans’ disastrous defeat by Hannibal at Cannae . This was the signal for many of Rome’s Italian allies to changed sides, but Praeneste was conspicuous among those that remained loyal; indeed Praenestine soldiers formed a large part of the Roman garrison that defended the besieged city of Casilinum in Campania until it faced starvation and was forced to surrender. According to Livy, Hannibal allowed the survivors to be ransomed, and those from Praeneste:

“... returned [there] in safety. ... with their commanding officer, M. Anicius ... To commemorate the event, [Anicius’] statue was set up in the forum of Praeneste, wearing a cuirass under his toga and with his head veiled. A bronze plate was affixed, with this inscription:

‘Marcus Anicius has discharged the vow he made for the safety of the garrison of Casilinum’.

The same inscription was placed beneath three other images (signa) in the temple of Fortuna”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 19: 17-8).

It seems that the Romans were extremely appreciative of the efforts of their Praenestine allies: according to Livy:

“The Senate decreed that the Praenestine troops should be granted double pay and an exemption for five years from further service. They were also offered the full Roman citizenship, but they preferred not to change their status as citizens of Praeneste”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 20: 2).

Thus, at this stage, Praeneste was proud of its independence from Rome and content with its status as a respected ally of Rome. However, it seems that, as the Romans’ military power increased, their respect for their allies deteriorated. This is exemplified by an event that took place in173 BC, when, according to Livy, one of the new consuls, L. Postumius Albinus, was:

“ ... angry with the Praenestines because he had received no marks of honour when he had gone there previously in a private capacity in order to offer a sacrifice in the temple of Fortuna ... So, before he left Rome [for Praeneste as consul], he sent a message... ordering [its] chief magistrate to meet him as he approached,to have a place prepared by the municipality where he could stay, and to see that pack animals were ready to carry his luggage when he left. No one before this consul had ever been a burden on ... the allies. ... Even if Postumius’ vindictiveness had been justifiable, he ought not to have acted on it while he was in office. Unfortunately, the Praenestines ... allowed the matter to pass without protest, and this silence allowed the magistrates to establish an unquestioned precedent for demands that became ever more burdensome”, (‘History of Rome’, 42: 1: 6).

These ‘ever more burdensome’ demands contributed to the ever more serious tension between Rome and the Italians that culminated in the Social War. We hear no more about relations between Praeneste and Rome in the run-up to this war, but they are unlikely to have improved: as Christopher Dart (referenced below, at p. 56) pointed out, the surviving sources do record:

“... a number of particularly extreme examples of Roman brutality towards communities of allied and Latin status in Italy in the 120s BC.”

According to the surviving epitome of Livy’s now-lost Book 60, in 125 BC:

“The praetor L. Opimius accepted the surrender of the rebellious [Latin colonists at Fregellae] and sacked Fregellae [itself]”, (‘Perioche’, 60: 3).

This rebellion had probably been caused by the colonist’s desire for Roman citizenship, and the Romans’ cruel reaction was all the more shocking because Fregellae had been one of the most loyal of the Latin colonies throughout the 200 years of it existence. None of the other Latins came to the assistance of Fregellae, but that was probably because of the triumph of fear over inclination. In any case, a body of opinion in Rome favoured a more conciliatory approach to the allies: the Plebeian Tribune, C. Gracchus, began to agitate for the enfranchisement of the Latins in 122 BC but his led to a battle in Rome in which Gracchus and the other leaders of the revolt wee killed. Things seemed to be getting out of control once more, and Christopher Dart (referenced below, at pp.60-1) suggested that this probably triggered the conciliatory legislation that extended Roman citizenship at least to local Latin élites (such as the Caesii of Praeneste).

Thus, by 112-1 BC, when the newly-enfranchised L. Caesius launched his political career as a triumvir monetalis, it might well have seemed that Rome and its allies would ultimately resolve their differences. However, in order to compete in the arena of Roman politics, he would surely need to do more on his denarii than simply ‘draw legitimacy from his extended family connection to Praeneste’. In the folowing section, I argue that, in deciding on the iconography of his denarii, he was intent upon:

✴demonstrating his pride in both of his fatherlands; and

✴stressing the fact that they their shared their Latin heritage.

There is also some circumstantial evidence that might throw light on the political leanings of the Caesii: Sandra Gatti (referenced below, at p. 78) observed that:

“... epigraphic evidence proves, without a shadow of a doubt, that the monumental sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia at Praeneste was realised [in its final form] in the last decades of [the 2nd century BC], since the magistrates who were recorded in relation to [its] reconstruction] ... all belonged to the most important families of Praeneste, [and these families] almost completely disappeared after Sulla [took his revenge on the pro-Marian city in 82 BC]”, (my translation).

Since an inscription (CIL XIV 2980) from Praeneste, records that C. Caesius, son of Marcus, served as one of the duoviri quinquennales of the Sullan colony within a few decades of its foundation, we can reasonably assume that the Caesii were not overtly associated with the populist faction of C. Marius (who first won office as tribune of the Plebs in 119 BC and was subsequently elected as consul on seven occasions before his death in 86 BC).

As we have seen, Ovid (above) recorded that the Roman altar of the Lares Praestite had been vowed by ‘that man from Cures (voverat illa quidem Curius)’. Harriet Flower (referenced below, at p. 109) pointed out that, although the passage in which is not completely secure (because of problems with the surviving manuscripts):

“It may be that Ovid is saying that this cult was originally native to the Sabine town of Cures. If so, [then] these lares are the ones introduced to Rome by Titus Tatius, Romulus’ fellow-king after the Sabine community had joined with the original population [of Rome].”

She cited the Varronian passage that I used above for the legendary origin of the Roman cult of Vediovis (which I re-quote here to include additional relevant material):

“...the ‘Annals’ record that [Titus Tatius] vowed altars to [a number of gods including] Vediovis and ... Vulcan and ... likewise ... the Lares ....”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 5: 74, translated by Roland Kent, at p. 71).

She also pointed out (at p. 111) that the location of the Roman altar of the Lares Praestites is unknown, but she observed that the iconography of this coin:

“... could suggest that [it was close to] a shrine of Vulcan such as the Volcanal, a very ancient sacellum in the Forum, ... [which was though to be the site of the altar dedicated by] Titus Tatius.”

In other words, seen through Roman eyes, this iconography might well have advertised the fact that Caesius’ two ‘fatherlands’, Praeneste and Rome, shared the ancient cults of Vulcan and the Lares Praestites.

This is most evident on the unprecedented iconography on the reverse of theses coins, which combines Vulcan and the Lares Praestites: I argued above that, seen through Roman eyes, this iconography might well have suggested a link between:

Caesius’ native Praeneste; and

the ancient Roman cult sites of Vulcan and the Lares Praestites, which were possibly located in close proximity to each other in the Forum.

I also pointed out that Varro had believed that these two cults, like that of Vediovis, had been brought to Rome by Titus Tatius. I now suggest that:

the god that Caesius chose to portray on the obverse of his coin was the Roman Vediovis, the young Jupiter, whose attribute was (pace Ovid) was the thunderbolt; and

he made this choice in order to suggest a parellel between this cult and the Praenestine cult of Jupiter Puer, the infant Jupiter, at the splendid new sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia at Praeneste, which was located at the spot at which Caeculus, the founder of Caesius’ city of origin, had been born.

Presumed head of Fortuna (late 2nd century BC)

From the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia, Praeneste

Now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Palestrina

We might therefore look again at Cicero’s reference to a statue of Jupiter Puer in the sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia there: in the relevant passage, Cicero noted that the place in which the lots of Fortuna had been found:

“... is fenced off in accordance with religious rules (locus saeptus religiose) to this day. It is hard by [the statue] of the child Jupiter (Iovis pueri), who is represented as sitting with Juno in the lap of Fortuna and reaching for her breast, which is held in the highest reverence by mothers”, (‘On Divination’, 2: 85, translated by William Falconer, at pp. 467-9).

Cicero’s wording suggests that the statue group was primarily associated with the veneration of the infant Jupiter, and it is generally accepted that:

✴it originally stood on the statue base that survives in front of the exedra of the eastern part of the so-called Terrazza degli Emicicli in the sanctuary; and

✴the over-life-sized female bust (late 2nd century BC, illustrated above) that was found in the adjacent well was from the figure of Fortuna.

We might now look again at Servius’ version of the myth of the foundation of Praeneste, in which the sister of the divi fratres:

“... gave birth to a boy near the temple of Jupiter and abandoned him. Maidens who were fetching water found him near a fire, which was not far from the well, and lifted him up: that is why he is called the son of Vulcan”, (‘ad Aen’, 7: 678, translated by Jan Bremmer and Nicholas Horsfall, referenced below, at p. 49).

Jan Bremmer and Nicholas Horsfall (referenced below, at pp. 51-2) observed that:

“Servius' version does not specify which Jupiter [was worshipped at this temple], although the god was worshipped at Praeneste under three different epithets (Puer, Arcanus and Optimus) and occupied several temples [there]. In no way can we be certain which Jupiter[Servius] has in mind, but we happen to know from Cicero that, in the famous temple complex of Fortuna Primigenia, there was a separate sanctuary with a statue of Fortuna suckling Jupiter Puer, who, as Cicero relates, was worshipped especially by mothers. Was Caeculus supposed to have been exposed near this sanctuary?”

It seems to me that the fact that (in this version of the legend) the baby Caeculus was found near a well makes this a reasonable supposition, in which case, it is possible that Caeculus, like Jupiter Puer, was worshipped here, ‘especially by mothers’.

If there had been an obvious Roman parallel to Caeculus, then Caesius would presumably have portrayed him on the obverse of his coin (since Caeculus’ father and his uncles were depicted on the reverse). However, since this option was not available, he chose to draw a parallel between:

✴Jupiter Puer, who was closely associate with Caeculus at Praeneste; and

✴a young Jupiter who was venerated in Rome.

Denarius issued collectively by the 3 moneyers: 86 BC (RRC 350a)

Obverse: Young god, thunderbolt below

Denarius issued by Mn. Fonteius: 85 BC (RRC 353) Denarius issued by C. Licinius Macer: 84 BC ( RRC 354/1)

Obverse: Young god, thunderbolt below. Obverse: Young god holding a thunderbolt

To take this further, we need to look at three other coins (illustrated above) that had obverses that similarly depicted the head of an Apollo-like god with a thunderbolt, all of which were issued in the period 86-4 BC:

✴in the first two (RRC 350a and RRC 353), the thunderbolt was below the head on the obverse; while

✴in the third (RRC 354/1), the moneyer C. Licinius Macer had revived the obverse of L. Caesius.

Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at p. 364, 369 and 370 respectively) characterised the deity on the obverse as Apollo, and argued (at p. 369) that the monogram below his chin in Fonteius’ coin should again be read as ‘AP’, identifying him as Apollo.

As we have seen, James Luce (referenced below, at p. 25) insisted that the obverses of these coins depict Apollo. He therefore included these issues in his list of coin issues of Apollo (at p. 28) in the decade up to Sulla’e emergence as dictator in 82 BC. On this basis, he concluded (at p. 32) that:

“The choice of Apollo [on the obverses of coins minted at Rome in this period] was clearly deliberate, ... [and] shows that he became, in some sense, [both] the symbol and the patron of the government in power.”

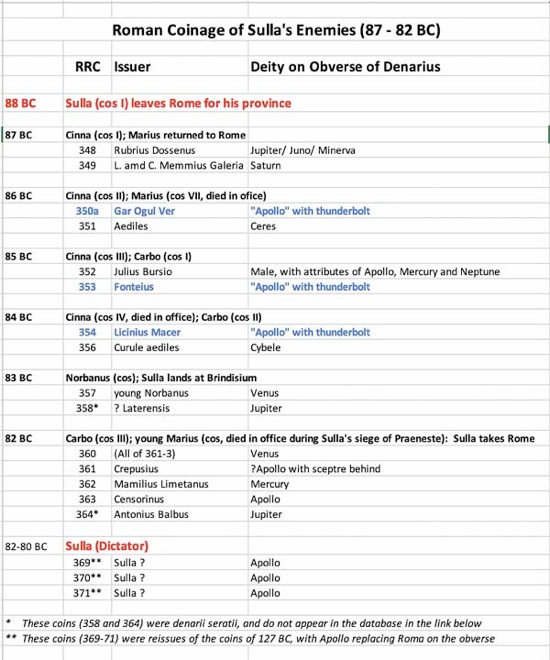

Denarii and denarii seratii minted at Rome in 87-2 BC (Michael Crawford, referenced below, 1974)

The denarii are contained in this extract from the on-line database of the American Numismatic Society

In the table above, I have revised Luce’s list of ‘Apollo’ coins in order to bring it into line with the chronology established by Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974). I have also restricted it to the period 88-82 BC, when Sulla was away from Rome. I have also tried to place the coinage of this period in its historical context. It seems to me that the period of Sulla’s absence from Rome falls into three distinct periods:

✴Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1964, at p. 143) argued that the coins (RRC 349) issued by the Memmii ex senātus consultato were struck for the populist Marius, after his return to Rome in 87 BC. His return heralded a period of violence in the city that subsided after his death in the following year.

✴Crawford argued (at p. 144) that the identical coins of that year (86 BC) were struck collectively by a ‘regular’, triumviral college:

“... reflecting, thereby, the return to normality at Rome after the death of Marius.”

L. Cornelius Cinna, who had been consul when Marius had been invited to return, was now in the ascendancy, and held the consulship in four consecutive years before he was killed by his troops in 84 BC.

✴Sulla returned to Italy from the east early in 83 BC, and Italy was then engulfed by civil war. Marius’ son, who headed the resistance to Sulla, found himself trapped when Sulla laid siege to Praeneste in 82 BC: he committed suicide just before that city fell to Sulla’s forces.

Sulla himself finally took Rome and was proclaimed dictator in late 82 or early 81 BC. Interestingly, three coins (RRC 369-71) that were issued at some time in 82-80 BC constituted a restoration of the coinage of 127 BC, except that the original head of Roma was replaced by the legend ROMA and the head of Apollo. Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1964, at pp. 144-5) argued plausibly that this restored issue:

“... was probably struck by Sulla after [his] capture of Rome in 82 BC, with the [twin] aims of continuing the regular coinage of the Republic without appointing extra moneyers and of proclaiming the defeat of his foes.”

If so, then this was a particularly clear example of Luce’s claim (above) that the government in power at this time chose to symbolise that power by representing Apollo on the obverses of coins that they minted at Rome.

If we now look back on the coins of the period of Sulla’s absence from Rome, it is clear that only those issued in 86-4 BC would have reflected the preferences of a government that actually exercised power in Rome in any meaningful sense: both before and after this interlude, Italy was in chaos. More specifically, in this three-year period of relative stability, it seems that power resided with Cinna. We might therefore reasonably assume that Cinna decided on the iconography of the coins that were issued from Rome at this time, and that the moneyers of 86 BC, who identified themselves as ‘GAR OGLV VER’, simply reflected this official preference. In respect of the other coins issued in this period:

✴RRC 351, which were issued by plebeian aediles in 86 BC and depicted Ceres on the obverse, would have financed the corn supply; and

✴RRC 356, which were issued by curule aediles in 84 BC and depicted Cybele, would have referred to their oversight of games held in her honour.

The situation in respect of the strange denarii (RRC 352) that the otherwise unknown L. Julius Bursio issued in 85 BC is almost completely obscure:

✴the obverse depicts the head of a male deity who has the attributes of Apollo (laurel wreath and ringlets), Mercury (winged head) and Neptune (trident behind); and

✴the reverse depicts the goddess Victory in a quadriga and (usually) the legend L.IVLI.BVRSIO.

In a minority of these denarii (RRC 352/1b), the reverse legend reads EX·A·P (ex argento publico), but Paul de Ruyter (referenced below) has demonstrated from the overlapping control marks that these too were issued by Bursio in Rome. The reverse is hardly likely to have celebrated Sulla’s victory over Mithridates’ general Archelaus at the Battle of Orchomenus in this year: it might have celebrated the victory of Cinna’s man, Fimbria, over Mithridates at the battle of Miletopolis in the previous year, or it might have represented a forlorn hope that it would be Fimbria rather than Sulla who would definitely defeat Mithridates. The significance of the obverse deity is completely obscure.

We know of coins issued by three moneyers from the gens Fonteia: the denarii from all three issues are contained in this extract from the on-line database of the American Numismatic Society:

✴C. Fonteius (RRC 290: 114-3 BC), who fought for Rome in the Social War and was killed at Asculum (‘Pro Fonteio’, 14) in 90 BC;

✴Mn. Fonteius (RRC 307: 108-7 BC); and

✴Mn. Fonteius, son of Caius (RRC 353: 85 BC), the moneyer under discussion here.

Cicero defended an M. Fonteius, whom he described as belonging to a prominent family from Tusculum, who seems to have been a moneyer at some stage before his quaestorship of 84 BC (‘Pro Fonteio’, 3-5), albeit that none of his coins survive. The most economical assumption is that:

✴Caius and the elder Manius were brothers; and

✴Marcus and the younger Manius were also brothers, and thus both the sons of Caius.

Thus, we see both the younger Manius and his brother (or, at least his kinsman) Marcus in the service of Cinna at this period. Nothing more is known about the younger Manius, but Cicero (‘Pro Fonteio’, 6) recorded that Marcus was a legatus in Spain at the time of Sulla’s return to Italy. He managed to continue in public life, serving as legate in Macedonia (‘Pro Fonteio’, 44) and was prosecuted in ca. 69 BC for alleged offences that he had committed as propraetor in Gaul. It is possible that the younger Manius could also have survived in public life after Sulla’s return: a coin (RRC 429/1) issued by P. Fonteius Capito in 55 BC refers on the reverse to a heroic action undertaken in battle by a military tribune, ‘MN·FONT·TR·MIL’, and Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at p. 453) suggested that the this could have been the younger Manius in action at the time of his brother’s propraetorship in Gaul. If so, then we might assume that he had not caused to much offence to Sulla by his action as moneyer in 85 BC, or at least that he had managed to keep a very low profile for a period thereafter.

On the basis of this information, we might assume that the younger Manius was

The winged child atop a goat on the reverse is identified variously as a symbol of Vediovis, young Jupiter, Cupid, or even an infant Bacchus. The inclusion of the caps of the Dioscuri and the thyrsus of Bacchus

The most interesting thing about these obverses, irrespective of the identity of the deity portrayed, is the sudden reappearance of his thunderbolt, which James Luce (referenced below, at pp. 37-8) characterised as a threat to annihilate Sulla.

However, the problem with this is that Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at p. 368) attributed another coin to Bursio: a very rare bronze coin (RRC 352/2, quinarius or sestertius), with:

✴the obverse depicting the head of a male deity with attributes of Apollo (laurel wreath and ringlets) and Mercury (winged head) , but with no trident behind; and

✴the reverse depicting Cupid breaking thunderbolt over knee.

If this is correct, and if the thunderbolt symbolised the power and intentions of Cinna at this time, then Bursio must have been an overt supporter of Sulla. James Luce (at p. 38 and not 66) rejected the attribution of this coin to Bursio, and argued that:

“... Sulla had something to say in reply [to Cinna’ thunderbolt]. A very rare and anonymous quinarius [RRC 352/2] appeared ... , doubtless issued from Sullan-held territory sometime in 83 or 82 BC. Sulla's answer was blunt and uncompromising; the reverse shows Cupid breaking the thunderbolt over his knee.”

In Construction Below

It seems to me that, even if the legend at Praeneste was framed in those terms in 112 BC, it would have not have been common knowledge among Caesius’ Roman ‘audience’. Thus while Vulcan on the reverse of the coins might well have signalled Caesius’ Praenestine origins, I doubt that the depiction of the Roman Lares Praestites would have served the same purpose.

Caesius Denarii

I suggest that Caesius’ intention in depicting the Lares Praestites on his coins was to underline their Latin/ Trojan origins and, thereby, the common Latin origins of both the cities of Latium (including Praeneste) and Rome: although most of our surviving sources record that the house gods that Aeneas brought from Troy to Lavinium were known to the Latins as the Penates, we also see them occasionally described in our surviving sources as Lares:

✴the poet Tibullus (ca. 30 BC) described Aeneas’ arrival in Italy as follows:

“Aeneas never-resting, brother of Cupid, ever on the wing, whose exiled barks carry the holy things of Troy, now doth Jove allot to thee the fields of Laurentum, now doth a hospitable land invite thy wandering gods (lares). There divinity shall be thine, when Numicius’ sacred waters carry thee to Heaven, a god of the native-born (indigetem). See, Victory is hovering above the weary ships. At last the haughty goddess comes to the men of Troy”, (‘Elegies’, 2: 39-46, translated by F. W. Cornish et al., referenced below, at p. 275).

✴Lucan (ca. 50 AD) imagined that, on the eve of the Battle of Thapsus (46 BC), Caesar had prayed for victory as follows:

“All ye spirits of the dead, who inhabit the ruins of Troy; and ye household gods (lares) of my ancestor Aeneas, who now dwell safe in Lavinium and Alba, upon whose altar still shines the fire from Troy; and thou, Pallas [an ancient statue of Athena], famous pledge of security, whom no male eye may behold in thy secret shrine: I, the most renowned descendant of the race of Iulus [i.e., Ascanius, the son of Aeneas], ... place incense .. upon your altars and solemnly invoke you in your ancient abode. Grant me prosperity to the end, and I shall restore your people: in grateful return, the Italians (Ausonidae) shall rebuild the walls of the Trojans, and a Roman Troy shall rise”, (‘Civil War’, 9: 990-9, translated by J. D. Duff, referenced below, at p. 579).

Finally, we should consider the significance of an inscription on a small cippus from the site of a sanctuary at Tor Tignosa, near Lavinium, which was first published as:

Lare Aineia d(onom);

and then, as reproduced in (CIL I, 2nd edition, 2843):

Lare Aenia d(onom.;

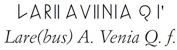

Adriano La Regina (referenced below, at p. 434) recently republished it in the form illustrated below:

From Adriano La Regina (referenced below, at p. 434)

Thus, while earlier scholars considered that the inscription had recorded a gift to Lar Aeneas (Aeneas, the ancestor), Adriano La Regina plausibly argued (at p. 435) that it recorded a gift made by a lady, Aula Venia, to the lares (in the plural). He dated the inscription to ca. 300 BC (at p. 435-6), and pointed out (at p. 436) that:

✴this inscription represents the earliest direct attestation of the cult of the Lares in Italy, and that no other surviving attestation of this kind is earlier than the 1st century BC;

✴other archeological evidence from this sanctuary indicated cult activity here between the 5th and 2nd centuries BC; and

✴the sanctuary was located in the heart of Latium, at the intersection of via Ardeatina and the road that connected Lavinium with Alba Longa.

Harriet Flower (referenced below, at p. 16) argued that Lares were specifically deities who protected places, and that those recorded in this inscription lived in and protected:

“... a local sanctuary in Latium, where their profile was low, and where they probably received regular offerings on a small scale.”

While that might be true, it seems to me that, in the light of:

✴the location of the sanctuary, on the road that linked Lavinium to Alba, both locations closely associated with legends surrounding the Trojan Penates; and

✴the passages by Tibullus and Lucan discussed above;

it would be odd if these Lares were not associated in some way with the pan-Latin Penates at Lavinium and, by extension, with the Lares Praestite and the (twin) dii Penates publici at Rome. Thus, it is at least possible that Caesius used the Lares Praestite on the reverse of his coin to underline that common religious heritage that he and his fellow Latins shared with the Romans.

Analysis and Conclusions

Eric Orlin (referenced below, 2010, at p. 18o) outlined the political climate in which these temples (among others) were dedicated: the Second Punic War had ended in 201 BC, and the new temple foundations at Rome in the following decades point to:

“... the Roman interest in suggesting that the Roman religious community extended throughout Italy [which was now, once more, securely in Roman hands]. This period saw a burst of new temple construction that is unparalleled in any other period of Roman history 15 new temples were definitely dedicated between 194 and 173 BC ... A remarkable aspect of these new temples is how many were dedicated to important divinities from the Italian peninsular ... The inclination to focus on Italian deities was demonstrated at the very outset of this period, ... [when] the Romans finally dedicated a temple [in Rome] to Juno Sospita, whom they had worshipped in common with the people of Lanuvium [in Latium] since 338 BC [see below].

Moved

We might reasonably wonder why Furius vowed two temples in Rome to Vediovis in 200-196 BC. [Temple of Honos et Virtus - Marcellus]

As noted above, the period 194-1 BC saw the dedication of five temples that had been vowed in battle by an individual who belonged (or who aspired to belong) to the military élite:

✴three of these temples were dedicated in 194 BC:

•the Temple to Fortuna Primigenia on the Quirinal, which had been vowed in 204 BC by the consul Publius Sempronius Tuditianus during the later stages of the Second Punic War;

•the Temple of Vediovis on the Tiber Island, which had been vowed in 200 BC by Lucius Furius Purpurio (as praetor) during an engagement with Gallic and Ligurian tribes in Cisalpine Gaul; and

•the Temple of Juno Sospita in the Forum Holitorium, which had been vowed in 197 BC by the consul Caius Cornelius Cethegus at the beginning of a battle in Cisalpine Gaul;

✴192 BC saw the dedication the Temple of Vediovis on the Capitol: Lucius Furius Purpurio had was vowed it as consul during another engagement with Ligurian tribes in Cisalpine Gaul in 196 BC; and

✴191 BC finally saw the dedication of the Temple to Iuventus on the Aventine side of the Circus Maximus, which the consul Marcus Livius Salinator had vowed in 207 BC during the Battle of Metaurus.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus dealt with Romulus’ association with this site (which Ovid mentioned in the quote above):

“... finding that many of the cities in Italy were very badly governed, ... [Romulus] undertook to attract fugitives from them ... His purpose was to increase the power of the Romans and to lessen that of their neighbours; but he invented a specious pretext for this initiative, making it appear that he was showing honour to a god: for he consecrated the place between the Capitol and the citadel (which is now called, in the language of the Romans ‘inter duos lucos’ (a term that described the actual conditions at that time, when the place was shaded by thick woods on both sides where it joined the hills) and made it an asylum for supplicants. He also built a temple there, but I cannot say for certain to which god or divinity he dedicated it . [Thus], under the colour of religion, he undertook to protect those who fled to [this consecrated location] from ... their enemies; and if they chose to remain with him, he promised them citizenship and a share of the land he should take from the enemy”, (‘Roman Antiquities’. 2: 15: 3-4).

Plutarch also wrote of a sanctified place of asylum here:

“... when Rome was first founded, they made a sanctuary of refuge for all fugitives, which they called the sanctuary of the God of Asylum. There, they received all who came, delivering none up (neither slave to masters, nor debtor to creditors, nor murderer to magistrates), declaring that they made the asylum secure for all men in obedience to an oracle from Delphi”, (‘Life of Romulus’, 9: 3).

I wonder whether, in some traditions, Dionysius’ Romulean temple here was dedicated to Plutarch’s ‘God of Asylum’, and whether the god in question was Vediovis ??

Having said that, the surviving evidence for the cult statue in the second of these temples is our most important source of information on the cult of this mysterious deity, followed by some numismatic evidence and (less usefully) by late speculation of the etymology of the name.

Vediovis in Etruria

Jean MacIntosh Turfa (referenced below, at p. 24) described a Etruscan liturgical calendar that contained entries for rituals of a number of gods, including Vetis/ Veove, the Roman Vediovis, to whom sacrifices were made on 24th September: this calendar was written on a linen scroll that had been reused to wrap an Egyptian mummy (now in the Archeological Museum of Zagreb and known as the Linen Book of Zagreb. Macintosh Turfa suggested that:

“... the book’s script, associated with the region of Perugia, is dated to ca. 200-150 BC”.

Karolina Sekita (referenced below, at p. 105 and note 58) recorded an inscription (ca. 300 BC) on a cup from the southern sanctuary at Pyrgi (Caere) that recorded vei[-]is, which she completed as Veivis, observing that this was very probably an Etruscan form of Vediovis. She concluded (at p. 109) that:

“... the name of Cavaθa’s paredros [i.e. her male cult companion) at the southern sanctuary at Pyrgi was Veivis, the underworld god, probably referred to in inscriptions as Apa (Father].”

She cited (at p. 107 and note 88) a passage from Macrobius to support her claim that:

“... the underworld character of [the Roman] Vediovis was well established in antiquity.”

In this passage (‘Saturnalia’, 3: 9: 10, translated by Robert Kaster, referenced below, at p. 69), Macrobius (5th century AD) claimed to reproduce a vow that the commander of the Roman army at the siege of Carthage in 146 BC to Dis Pater, Veiovis, and Di Manes if they would permit Carthage to fall. However, Henk Versnel (referenced below, at pp. 386-7) argued that:

“It does seem that [the vow, as Macrobius reproduced it], was put together by a priest or an antiquarian on the basis of ancient material, when circumstances made another devotio necessary, [but] the result is not a success in all respects. ... [Among other oddities], Veiovis (it has been observed many times) is a late intruder, as is Dis Pater. ... It is quite possible, therefore, that the [vow] on the occasion of the devotio of Carthage was (re)constructed from existing formulary material ...”

In other words, the late evidence of Macrobius cannot be relied on to indicate that Vediovis was ever considered to be a god of the underworld at Rome, even if circumstantial evidence might suggest that the Etruscan Veivis was a god of the underworld.

However, Gary Farney (referenced below, at p. 258) argued that Caesius’ made this choice because, like Vulcan, the Lares Praestites played a part in the foundation myth of Praeneste. In order to understand his argument, we might usefully start with Cato’s account (above) of this myth: Timothy Cornell (in T. J. Cornell (editor), referenced below, at Vol. III, at p. 114), in his commentary on it, argued that, although:

“Cato is the earliest [surviving] source to refer to the story of Caeculus, the founder of Praeneste, ... it was, beyond doubt, an ancient local myth with close affinities to other Italic foundation legends.”

He then drew attention (at p. 115) to the following record by Solinus (3rd century AD):

“... the books of the Praenestines say that the city was founded by Caeculus, whom (it is said) the sisters of the Digidii found, hard by a fortuitous fire”, (‘Polyhistor’, 2: 9).

Thus, it seems that the young girls mentioned by Cato were (or had become) the sisters of the Digidi. Cornell also drew attention to the fuller account of this myth given by Servius (4th century AD), in his commentary on the Virgilian passage mentioned above:

“There were, at Praeneste, two brothers who were called divine (duo fratres, qui divi appellabantur) When their sister was sitting near the hearth, a spark ... struck her womb, which, it is said, made her pregnant. Later, she gave birth to a boy near the temple of Jupiter and abandoned him. Maidens who were fetching water found him near a fire, which was not far from the well, and lifted him up: that is why he is called the son of Vulcan. He is called Caeculus because he had rather small eyes ... He later collected a band around him, lived as a robber for a long time, and finally founded the city of Praeneste in the mountains”, (‘ad Aen’, 7: 678, translated by Jan Bremmer and Nicholas Horsfall, referenced below, at p. 49).

Finally, Cornell pointed out (at p. 115) that, according to Verona Scholiast, Varro had recorded that Caeculus was brought up by the ‘Depidii’, and observed that that:

“... one suspects that divi in the phrase ‘duo fratres, qui divi appellabantur’ [Servius] is a corruption of Depidii [Varro] or Digidii [Solinus], whose sister was the mother of Caeculus.”

Gary Farney (referenced below, at p. 258) argued that:

“Caeculus’ divine uncles, [the divi fratres = the Depidii = the Digidii], ... are to be equated with the Lares Praestites, numina [divinities] with a name similar to ‘Praeneste’.”

Elizabeth Palazzolo (referenced below, at p. 209, note 414) pointed out that:

“This would not be the only questionable etymological origin story for Praeneste that circulated in antiquity: [for example, as discussed above], Cato derives the name [of Praeneste] from the mountains that it stands before (praestet).”

In other words, it is possible that the divi fratres/Depidii / Digidii = Lares of Praeneste = Lares Praestites, and that Caesius used them on the reverse of his denarii because, like Vulcan, they were associated with the foundation of Praeneste. Gary Farney (referenced below, at p. 258) then pushed this argument further by suggesting that Caesius’ family might have:

“.. used the similarity of its name and its Praenestine origins to claim descent from Caeculus, and so the reverse types [of Caesius’ denarii might] display the heritage of both sides of Caeculus’ [and thus, Caesius’] family:

✴Vulcan, [Caeculus’ father]; and

✴the Lares Praestites, [who were arguably] Caeculus’ divine uncles ...”

Miano D., “Fortuna: Deity and Concept in Archaic and Republican Italy “, (2018) Oxford

Badian E., “From the Iulii to Caesar”, in

Griffin M. (editor), “A Companion to Julius Caesar”, (2009) Chichester and Malden, MA, at pp. 11-22

Orlin E., “Temples, Religion and Politics in the Roman Republic”, (1997) Leiden, New York, Cologne

Kent (R., translator), “Varro: On the Latin Language, Volume I: Books 5-7”, (1938) Cambridge MA

Frothingham A. L., “Vediovis, the Volcanic God: A Reconstruction”, American Journal of Philology, 38: 4 (1917) 370-91

Read more:

Sekita K., “Śuri et al: A ‘Chthonic’ Etruscan Face of Apollon”, in

Bispham E. and Miano D. (editors), “Gods and Goddesses in Ancient Italy”, (2020) London and New York, at pp. 100-19

Holman T., “The Youthful God Revisited: Veiovis on Roman Republican Denarii”, Koinon, 2 (2019) 97-108

Roselaar S.’ “Italy's Economic Revolution: Integration and Economy in Republican Italy”, (2019) Oxford

Flower H., “The Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street Corner”, (2017) Princeton and Oxford

Warford E., “Stuck in the Middle with You: Vediovis, God of Transitions and In-between Places”, (2017) presented at the annual meeting of the Classical Association of the Middle West and South, April 5-8, Kitchener, Ontario

Dart C., “The Social War (91 to 88 BCE): A History of the Italian Insurgency against the Roman Republic” (2016) London and New York

Gatti S., “Il Santuario della Fortuna Primigenia”, in:

Tavano G. (editor), “Palestrina e il Santuario della Fortuna Primigenia”, (2016) Pescara, at pp. 61-78

Palazzolo E. G., “The Roman Cultural Memory of the Conquest of Latium”, (2016) thesis from the University of Pennsylvania

La Regina A., “Dedica ai Lari, non al Lare Aenia”, Epigraphica, 76 (2014) 33-6

Henriksén C., “A Commentary on Martial, Epigrams, Book 9”, (2012) Oxford

MacIntosh Turfa J., “Divining the Etruscan World. The Brontoscopic Calendar and Religious Practice”, (2012) Cambridge

Kaster R. A., “Macrobius: Saturnalia: Voll. I, Books 1-2; and Vol. II, Books 3-5”, (2011) Cambridge (MA)

Farney G., “Ethnic Identity and Aristocratic Competition in Republican Rome” (2010) Cambridge

Orlin E., “Foreign Cults in Rome: Creating a Roman Empire”, (2010) Oxford

Wiseman T. P., “Remembering the Roman People: Essays on Late-Republican Politics and Literature”, (2009) Oxford and New York

Bispham E., “From Asculum to Actium: The Municipalisation of Italy from the Social War to Augustus”, (2008) Oxford

Brennan T. C., “The Praetorship in the Roman Republic”, (2000) Oxford

Cornell T. J.(editor), “The Fragments of the Roman Historians”, (2000) Oxford

De Ruyter P. H., "The Denarii of the Roman Republican Moneyer Lucius Julius Bursio: a Die

Analysis", Numismatic Chronicle, 156 (1996) 79-147

Bremmer J. N. and Horsfall N. M., “Roman Myth and Mythography”, (1987) Groningen

Scullard H. H., “Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic”, (1981) London

Versnel H. S., “Two Types of Roman Devotio”, Mnemosyne , 29:4 (1976) 365-410

Crawford M., “Roman Republican Coinage”, (1974) Cambridge

Briscoe, J., “A Commentary On Livy: Books 31-33”, (1973) Oxford

Weinstock S., “Divus Julius”, (1971) Oxford

Wiseman T. P., “New Men in the Roman senate (139 BC - 14 AD)”, (1971) Oxford

Luce T. J., “Political Propaganda on Roman Republican Coins (ca 92-82 BC)”, Journal of Archaeology, 72:1 (1968) 25-39

Crawford M., “Coinage of the Age of Sulla”, Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society, 4 (1964) 141-58

Rackham H, (translator), “Cicero: ‘On the Nature of the Gods’”, (1933), Cambridge (MA)

Frazer H. G. (translator,), “Ovid: ‘Fasti’”, (1931), Cambridge (MA)

Duff J. D.(translator), “Lucan: The Civil War (Pharsalia)”, (1928), Cambridge (MA)

Cornish F. W. et al. (translators), “Catullus. Tibullus. Pervigilium Veneris”, (1913), Cambridge (MA)

Warde Fowler W., “The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic”, (1899) London

Montague L., “The Meaning of the Monogram on Denarii Struck by Caesius and Manius Fonteius”, Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society, 15 (1895) 162-3

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)