Roman Pre-History

Date of the Foundation of Rome II:

Eratosthenes of Cyrene

Linked Pages: Date of the Foundation of Rome I: Timaeus

Roman Pre-History

Date of the Foundation of Rome II:

Eratosthenes of Cyrene

Linked Pages: Date of the Foundation of Rome I: Timaeus

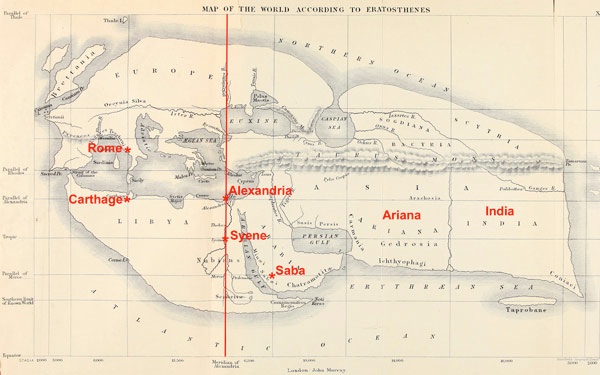

Mediterranean powers at the time of Eratosthenes (adapted from Wikipedia)

As Edward Bispham and Timothy Cornell (in Cornell T. J. (editor), referenced below, Vol. I, at p. 163) pointed out, Q. Fabius Pictor (died after 216 BC):

“... was the first Roman to write a history of his city ... , and he did so in Greek.”

Unsurprisingly, when Fabius gave a date for the foundation of his city, he also did this ‘in Greek ‘: according to Dionysius of Halicarnassus (7 BC):

“... Q. Fabius [places the foundation of Rome] in the first year of the eighth Olympiad, [the year that we call 748 BC]”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 74: 1).

I discuss Fabius’ dating and those of subsequent scholars in my page Date of the Foundation of Rome III: from Q. Fabius Pictor. However, we should first deal with the comparable dates given by two earlier Greek scholars whose works provided the basis for these later refinements:

✴Timaeus of Tauromenium (see the page Date of the Foundation of Rome I: Timaeus Date of the Foundation of Rome I: Timaeus); and

✴Eratosthenes of Cyrene (discussed in this page).

Eratosthenes of Cyrene

Eratosthenes’ Background

Duane Roller (referenced below), who outlined (at pp. 7-15 and pp. 268-79) the few surviving biographical data relating to Eratosthenes, suggested (at p. 268) that he had probably been born during the 124th Olympiad (284-1 BC). At this time, his native Cyrene (in modern Libya)was under the hegemony of Ptolemy Lagides, one of the seven somatophylakes (bodyguards) of Alexander the Great, who had taken possession of both Egypt and Cyrene after Alexander’s death in 323 BC. Duane Roller (referenced below, at p. 8) characterised Cyrene in the 3rd century BC as:

“...a prosperous and cosmopolitan outpost of Greek culture, lying between Egyptian and Carthaginian territory...” ; and

observed (at p. 10) that Eratosthenes’ upbringing there had:

“... exposed him to exotic contacts at [the western] end of the Greek world ...”.

He also noted (at pp. 8-9) that, by the late 260s BC, Eratosthenes had left Cyrene for Athens, where he was exposed to a wide variety of scholarly disciplines. According to the Byzantine encyclopaedia (10th century AD) known as the ‘Souda, he became:

“... a student of the philosopher Ariston of Chios, the philologist Lysanias of Cyrene, and the poet Callimachus. He was summoned from Athens [to Alexandria] by Ptolemy III [(246-222 BC), the husband of Berenice of Cyrene], and he lived until Ptolemy V [(204-180 BC)]”, (E: 2898, translated by Duane Roller (referenced below, at p. 268).

Eratosthenes and the Library at Alexandria

Alexander the Great founded the city Alexandria in the Nile delta, and it had sprung to prominence in 305 BC, when Ptolemy Lagides had declared himself Pharaoh as Ptolemy I Soter (‘Saviour’) and moved his capital there from Memphis. By the time of Eratosthenes’ arrival, the city boasted an important library and, as Duane Roller (referenced below, at p.10) pointed out, the most distinguished academic post in Alexandria was that of librarian, which often carried with it the position of royal tutor. As the early history of the library is only sketchily outlined in our surviving sources, and the identities of both its founder and its first librarian are both disputed: broadly speaking, it was either:

✴founded by Ptolemy I, with Demetrius of Phalerum (see above) as the first librarian after his exile from Athens in 307 BC; or

✴founded by Ptolemy II, with Zenodotus of Ephesus as the first librarian.

As Roger Bagnall (referenced below, at pp. 349-51) pointed out, there is no real basis for either hypothesis (or for any combination of the two). One of the so-called Oxyrhynchus papyri (2nd century AD) records that Eratosthene was appointed to this post, succeeding:

“... [Apollonius of Rhodes], a student of Callimachus and the teacher of the first [??] king”, (Oxyrhynchus Papyrus: 1241, col. 2: 1-8, from a translation reproduced by Duane Roller, referenced below, at pp. 268-9).

It is therefore generally assumed:

✴that Apollonius and Eratosthenes were, respectively, the second and third librarians at Alexandria;

✴Eratosthenes held this post from ca. 246 BC until his death in ca. 200 BC; and

✴all of his known works belong to this period.

Eratosthenes’ Measurement of the Circumference of the Earth

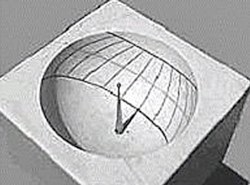

Hemispherical sundial that would have been used for astronomical calculations at the time of Eratosthenes

From this t essay (2005) by Newlyn Walkup

Duane Roller (referenced below at p. 12) noted that Eratosthenes’ early work seem to have had an emphasis on mathematics: for example, the still-famous Archimedes of Syracuse (287-212 BC) acknowledged prior discussions with Eratosthenes in the preface to the ‘Method of Mechanical Theorems’ (see Roller’s translation of the relevant passage at p. 270). Roller commented that:

“This would have given Eratosthenes great credibility as a mathematician and prepared him for the treatise that would lead him from mathematics to Geography: his ‘On the Measurement of the Earth’.”

It is worth digressing at this point to discuss Eratosthenes’ calculation of the circumference of the earth in some detail, since it illustrates the skills that he was to bring to his work on chronography. As Duane Roller (referenced below, at p. 7) pointed out, Aristotle had produced a value of 400,000 stadia, and his followers in the generation before Eratosthenes had developed Aristotle’s work on the physical characteristics of the lands of the new Macedonian Empire, to the extent that:

“...the study of the earth had reached the point where Eratosthenes was able to pull all former thought together and use his own original mind to create the discipline of geography.”

Our knowledge of Eratosthenes‘ method comes from a book called the ‘Caelestia’ (Heavens) by an astronomer called Cleomedes: according to Alan Bowen and Robert Todd 9referenced below at p. 3), it was probably published in the period 50 BC - 250 AD. The relevant passage ( Caelestia’ 1: 7) is translated by Duane Roller, referenced below, at pp. 265-6). The prose is relatively impenetrable, but the key facts are as follows:

✴Eratasthenes believed that Alexandria was on the same meridian as the city of Syene (modern Aswan) to the south (see the map below).

✴Eratosthenes was aware that, at the summer solstice:

•the gnomen (upright) on the sundials at Syene cast no shadow because the sun is directly overhead; and

•the arc of the shadow in the hemispherical bowl of the sundial at Alexandria measured 1/50th of its circumference (as illustrated above).

At this point, Eratosthenes must have used Euclidean geometry to prove that the length of the arc along the ground from Alexandria to Syene must have been 1/50th of the circumference of the earth. (The mathematically inclined will find the proof of the Euclidean theorem underlying the excellent essay (2005) by Newlyn Walkup mentioned above. Cleomedes believed that the distance from Alexandria to Syene was 5,000 stadia, indicating that the circumference of the earth was 50 x 5,000 = 250,000 stadia. However, Eratosthenes’ figure was actually 252,000 stadia (see, for example, Strabo, ‘Geography’, 2: 5: 34 and Pliny the Elder, ‘Natural History’, 2: 112), which mens that he had actually estimated the distance from Alexandria to Syene was 5,040 stadia.

We can now look at the accuracy of Eratosthenes’ calculation:

Dmitry Shcheglov (referenced below, at p. 172) observed that the Eratosthenes’ the figure of 360/5 = 7.2º for the latitudinal difference between Alexandria and Syene is close to the modern value of 31.19º (Alexandria) - 24.09º (Syene) = 7.1º.

✴We can use a passage by Pliny the Elder in order to convert his 5,040 stadia into meters: he recorded that the forests of Saba (biblical Sheba in Arabia) extended over an area of 20 10 schoeni: (expressed here in a unit of length used in Egypt and Persia) and then explained that:

“According to the estimate of Eratosthenes, the length of the schoenus is 40 stadia, or, in other words, 5 [Roman] miles; some persons, however, have estimated the schoenus at no more than 32 stadia”, ‘Natural History’, 12: 30).

Clearly, Pliny regarded the stadion as a stable unit of length that was equivalent to an eighth of a Roman mile: since the latter was 1485 meters, Eratosthnes’ stadion was equivalent to 185 meters, which indicates that Eratosthenes assumed that the distance from Alexandra to Syene was 936 km. However, as Dmitry Shcheglov (referenced below, at p. 172) observed, Google Maps gives 843.6 km for the straight-line distance between Alexandria and Syene, which means that Eratosthenes‘ figure is 17% too high.

Some scholars have ignored Pliny’s synchronisation of Eratosthenes‘ stadion and the Roman mile and worked backwards from an allegedly standard schoenus of 0.525 metres to calculate that Eratosthene’s stadion was 516 meters in order to arrive at a distance from Alexandria to Syene that is within 1-2% of the modern value. However, as Dmitry Shcheglov (referenced below, at p. 156) pointed out:

“Our main sources emphasise that the schoenus, unlike the stadion, was a very uncertain measure: it could vary fourfold, from 30 to 120 stadia. Therefore, it would be more reasonable to define the schoenus through the stadion, as Pliny clearly does in the quoted passage, and not vice versa.”

Sadly, then, the often-made claim that Eratosthenes’ calculation was extraordinarily accurate is simply the result of a circular argument. Nevertheless, if he had the benefit of ‘Google Maps’, then his methodology would indeed have delivered a very respectable value for the earth’s circumference: 50 x 843.6 = 42,180 km, as opposed to the actual value of 40,075 km, an error of slightly over 5%.

Eratosthenes’ ‘Geographika’

Reconstruction of Eratosthenes’ map of the oikoumenē (inhabited world) (Wikipedia)

From Bunbury, E.H. , “A History of Ancient Geography among the Greeks and Romans

from the Earliest Ages till the Fall of the Roman Empire”, (1883) London, at p.667

Duane Roller (referenced below at pp. 13-4) argued that Eratosthenes had probably completed his earliest surviving major work, the ‘Geographika’, by 218 BC (since it dealt in detail with Illyrium, on the Greek mainland, but did not reflect the Romans’ expansion into Illyria at that time). He observed (at p. 6) that the the impetus for the work would have come from military campaigns of Alexander the Great in 336 - 323 BC, which had led to a widening of horizons and given rise to:

“... a large of amount of [new] data, especially about the remote eastern parts of the world, which was made accessible by the published reports of those with [Alexander], many of which were the primary sources of Eratosthenes.”

Most of this material would have been catalogued and preserved in the library at Alexandria. Roger Bagnall (referenced below at pp. 360-1) observed that, although there is little surviving evidence for the early history of the Library, it certainly;

“... served as the base for a wide range of [philological and] other scholarly activities, scarcely possible without its rich array of texts. I cannot evoke here anything like the full range of intellectual pursuits supported by the Library’s collections, but they included many attempts to compile systematic information about different subjects. One example is geography, where Eratosthenes was able to make decisive progress in creating the mathematical foundations of that subject and enabling the development of cartography.”

Although the original work is now lost, much of it can be reconstructed from fragments cited by Strabo and other later writers: the recent book by Duane Roller (referenced below), which has provided the backbone on this part of my discussion of Eratosthenes, contains a translation and commentary on all of these surviving fragments.

For our present purposes, it is interesting to note Strabo’s disgusted:

“... when Eratosthenes actually places Rome on the same meridian with Carthage (see the map above) although Rome is, in fact, much farther west of the Strait of Sicily even than Carthage). [In so-doing], his ignorance of both of these regions and of the successive regions toward the west as far as the Pillars [of Hercules] can reach no higher extreme (‘Geography’, 2: 1: 40).

It is certainly true that the ‘Geographika’ concentrated almost exclusively on the lands to the east of the putative meridian of Alexander and Syene (see the map above). However, Eratosthenes can hardly have been ignorant of the region around Carthage, since it bordered Cyrene. Indeed, an earlier comment by Strabo indicates that Eratosthenes had some appreciation of the systems of government at both Rome and Carthage:

“... towards the end of his [‘Geographika’], after withholding praise from those ... who had advised Alexander [the Great] to treat the Greeks as friends and the Barbarians as enemies, Eratosthenes argued that it would be better to make such divisions according to [merit], ... since many Greeks are bad, while many Barbarians are refined: [consider], for example, Indians and Arians, and also Romans and Carthaginians, who carry on their governments so admirably. And this, [according to Eratosthenes], is the reason why Alexander, disregarding his advisers, welcomed as many men of good repute as possible ...” (‘Geography’, 1: 4: 9).

Finally, he would hardly have been ignorant of the fact that the Romans had emerged victorious in the First Punic War (264 - 241 BC) and had expelled the Carthaginians from Sicily and Sardinia.

Eratosthenes’ ‘Chronographiai’

Sarah Davies (referenced below, at p. 26) observed that:

“Eratosthenes’ [geographical] work in the 3rd century BC laid the groundwork for ... [later] perceptions of the oikoumenē (inhabited world). The significance of Eratosthenes’ contribution resided in its effort to standardise ... [and] universalise a schema of the oikoumenē, in the same way that [he] had introduced Olympiads to standardise timescales.”

Duane Roller (referenced below, at p. 14) made a similar point: along with his geographical work, Eratosthenes:

“... began developing chronological theory, a concept that, in a way, was connected with his geographical concerns:

✴his first work on this topic was the ‘Olympionikai’, on the ... lists [of the winners of races at successive four-yearly Olympiads]; and ...

✴this led to a broader chronological treatise, the ‘Chronographiai’, [perhaps] the first [pan-Hellenic] chronology of Greek history from the fall of Troy to the death of Alexander the Great [in in Ol. 114: 2, the year that we call 323 BC, a period that he] calculated at 860 years.

Astrid Möller (referenced below, 2005, at p. 245) observed that:

“Ancient Greek chronography developed when historians began to ask for temporal distances between past events and themselves. As long as there was no fixed point of reference (i.e., a common era, each event had to be located in time in relation to other events, and this relation was expressed by intervals in years or generations. ... [A good example of this method of bridging] the time span into the past by:

✴adding intervals between events ... ; and

✴arranging a sequence of periods [/eras/ ages] given by years;

can be seen in the famous fragment from [Eratosthenes’] ‘Chronographiai’ ...”

This famous fragment was preserved (or perhaps summarised) by Clement of Alexandria (‘Stromata’, 1: 102):

“Eratosthenes defines the ages as follows:

from the fall of Troy until the return of the Heraclidae: 80 years;

from these until the settlement of Ionia: 60 years;

from this until Lycurgus’ guardianship [at Sparta]: 159 years;

from this until the year preceding the first Olympiad: 108 years;

from this Olympiad until the invasion of Xerxes; 297 years;

from this until the beginning of the Peloponnesian War: 48 years;

from this until its end and the defeat of the Athenians; 27 years;

from this until the battle of Leuctra: 34 years;

from this until Philip’s death: 35 years;

from this until the death of Alexander: 12 years”.

Astrid Möller (referenced below, 2005, at p. 246) noted that:

“[Eratosthenes’] dates from Xerxes onwards are corroborated by other evidence and easily convertible into years BC ...”

She elaborated (at p. 254):

“... there is not much doubt that Alexander the Great died in 323 BC; the battle of Leuctra took place in 371 BC; the Peloponnesian War began in 431 BC; and Xerxes invaded Greece in 480 BC.”

Thus, for example:

✴working backwards in time, the first four-yearly Olympiad began in Ol. 1: 1 = 776 BC (480+297); and

✴working forwards in time, Alexander the Great died 453 years (776 -323) after Ol. 1: 1 = Ol. 114: 2.

Moving back in time in Eratosthenes’ list from Ol. 1: 1, we come to Lycurgus of Sparta. According to Plutarch:

“... nothing can be said about Lycurgus the lawgiver that is not disputed: there are different accounts of his birth, his travels, his death, and above all, of his work as lawmaker and statesman; and there is least agreement among historians as to the times in which he lived.

✴Some say that he flourished at the same time with Iphitus [of Ellis] and that, together, they established the Olympic truce to facilitate the holding of the first Olympic games]. Among these is Aristotle the philosopher, and he alleges as proof the inscription of the discus at Olympia, which preserves the name of Lycurgus.

✴But those like Eratosthenes and Apollodorus, who worked this date out by computing the time of the successions of the Spartan kings, prove that Lycurgus was many years earlier than the first Olympiad.

✴Timaeus (see below) conjectures that there were two [important med called] Lycurgus at Sparta at different times, ... [and] that the elder of the two lived not far from the times of Homer ...”, (‘Life of Lycurgus’, 1: 1-2, with the phrase underlined translated by Nikos Kokkinos , referenced below, 2009, at p. 38) )

Thus, while Aristotle had dated Lycurgius; guardianship to Ol. 1: 1, Eratosthenes had dated it 108 years earlier. Interestingly, Eusebius (ca. 300 AD) recorded that:

“Aristodemus of Elis, [a historian of uncertain date], relates that, in the 27th Olympiad after Iphitus, the names of the winners in the athletic contests began to be recorded. Before then the athletes' names were not recorded’, (‘Chronicle’, 1: 90).

Astrid Möller (referenced below, 2005, at p. 254) observed that Eratosthenes had inserted precisely the period of 27 Olympiads between Lycurgus and Ol. 1: 1, and that this is reflected Aristodemus’ 27 Olympiads in which the names of the winners were allegedly unrecorded (in which case, Eratosthenes’ Ol. 1: 1 would have been the date of the first recorded Olympiad.

However, this observation begs a question: how did anyone know that there had been 27 Olympiads before Ol. 1: 1 if they had been unrecorded? Astrid Möller (referenced below, 2005, at p. 254) argued that Eratosthenes:

“... gave Lycurgus an authoritative date [by reconciling] the divergent traditions of the Spartan king list and the relatively new Olympiad era.”

However, Nikos Kokkinos , referenced below, 2009, at p. 38) argued that, at the time of Eratosthenes:

“... nobody knew the actual lengths of the reigns of the early [Spartan] kings ... : [on the basis of the correct translation, underlined above], Plutarch implies that Eratosthenes, in the first place and by unspecified means, would have been responsible for calculating a version of the royal [Spartan] chronology.”

He pointed out (at pp. 40-1) that, shortly before Eratosthenes’ time, the Hellenised Egyptian priest Manetho of Sebennytus had published, in Alexandria, his ‘Aigyptiaka’ (Egyptian History), which had included Egyptian king lists (known from later epitomes).

As John Dillery (referenced below, at pp. xxx-xxxi) observed:

“By synchronising the fall of Troy with the reign of the ‘Thyoris’, Manetho, in one economical action, also situated the watershed event of the Greek past, divided between myth and history on the grid of Egyptian time.”

‘Thyoris’ is better known as Twosret or Tausret, whose independent rule can be dated to 1191 - 1189 BC.

Furthermore, since we can independently date the death of Alexander to 323 BC, Eratosthenes’ dating of the first Olympiad to 453 years thereafter allows us to to date it to 776 BC:

✴Astrid Möller (referenced below, 2004, at p. 178) argued that it is ‘very likely’ that this dating was established by Eratosthenes himself; while

✴David Asheri (referenced below, at p. 53, note 1) argued that, although is not attested before Eratosthenes, it had been ‘almost certainly’ known to Timaeus some decades earlier.

Whether or not Eratosthenes was responsible for this dating of Ol, 1: 1, it seems to have become canonical thereafter.

“From when Troy was taken, 945 years, in the <2>2nd year that [Menesthe]us was king of Athens, on the 7th day before the end of the month Th[argelio]n.

More generally, Dionysius of Halicarnassus (see below) recorded that:

“In another [now-lost] treatise in which I demonstrated how Roman chronology is to be synchronised with that of the Greeks, I established that the canons of Eratosthenes are sound”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 74: 2).

Having said that, the grammarian Censorinus (3rd century AD) recorded that there was divergence of view between scholars as to the number of years between Ol, 1: 1 and the fall of Troy:

“Sosibius [wrote that this period was 395 years long; Eratosthenes that it was 407 years; Timaeus that it was 417, Aretes that it was 514, and others have computed it in other ways. Their disagreement shows that it is [still] uncertain”, ‘De Die Natali Liber’, 21: 3, translated by Astrid Möller, referenced below, 2005, at p. 258).

However, it is not possible to say whether this reflects differences in relation to one or other of these canons, or to both of them.

Eratosthenes and the Foundation of Rome

According to Servius, in his commentary on Virgil’s ‘Aeneid’:

“Eratosthenes reports that Romulus, [the son] of Aeneas’ son, Ascanius, was the originator of the City”, (‘ad Aen.’, 1: 273, translated by Peter Wiseman, referenced below, 1995, at p. 167).

Thus, it seems from this passage that Eratosthenes believed that Rome had been founded within two generations of the fall of Troy. As we have seen, he dated the the fall of Troy to 860 years before the death of Alexander = 1183 BC, which implies a date for the foundation of Rome of ca. 1100 BC.

An observation by Peter Wiseman (referenced below, 2015, at p. 45) might well explain the circumstances in which the Greeks first became aware of the Romans’ Romulus and Remus: immediately after the Romans’ victory over Carthage in the First Punic War (264 -241 BC), they sent ambassadors to King Ptolemy III at Alexandria to offer their assistance with his war with King Antiochus of Syria:

“King Ptolemy will certainly have taken the Roman ambassadors to see the famous library of Alexandria. The librarian at the time was the great polymath and historian, Eratosthenes ...”

They would presumably have told Eratosthenes about Romulus and Remus, the putative grandsons of Aeneas.

According to the Latin grammarian C. Julius Solinus (3rd century AD):

“[Fabius] Pictor believes [that that Rome was founded] was during the 8th [Olympiad = 748-4 BC; Cornelius Nepos ], seconding the opinions of Eratosthenes and [his follower], Apollodorus, think it was founded in the 2nd year of the 7th Olympiad [= 751 BC]”, (‘Polyhistor’, 1: 27).

(although Christopher Smith, for example, in Cornell T. J. (editor), referenced below, Vol. III, at p. 455) expressed doubts about the citation to h

Read more:

Davies S., “Rome, Global Dreams and the International Origins of an Empire”, (2020) Leiden

Shcheglov D, A., “The So-called ‘Itinerary Stade‘ and the Accuracy of Eratosthenesʼ Measurement of the Earth”, Klio, 100:1 (2018) 153–77

Wiseman T. P., “The Roman Audience: Classical Literature as Social History’, (2015) Oxford

Cornell T. J. (editor), “The Fragments of the Roman Historians”, (2013) Oxford

Roller D., “Eratosthenes’ Geography: Fragments Collected and Translated with Commentary and Additional Material”, (2010) Princeton and Oxford

Kokkinos N., “Ancient Chronography: Eratosthenes Dating of the Fall of Troy”, Ancient West and East, 8 (2009) 37-56

Möller A., “Epoch-Making Eratosthenes”, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 45 (2005) 245-60

Bowen A and Todd R., “Cleomedes' Lectures on Astronomy: A Translation of The Heavens”, (2004) Berkeley, Los Angeles and London

Geus K., “Measuring the Earth and the Oikoumene: Zones, Meridians, Sphragides and Some Other Geographical Terms used by Eratosthenes of Kyrene”, in:

Talbert R. and Brodersen K. (editors), “ Space in the Roman World: Its Perception and Presentation”, (2004) Münster, at pp. 11–26

Möller A., “Greek Chronographic Traditions About the First Olympic Games”, in:

Rosen R. M. (editor),”Time and Temporality in the Ancient World”, (2004) Philadelphia PA, at pp. 169-84

Bagnall R. S., “Alexandria: Library of Dreams”, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 146:4 (2002) 348-62

Dillery J., “The First Egyptian Narrative History: Manetho and Greek Historiography”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 127 (1999), 93-116

Wiseman T. P., “Remus: a Roman Myth’, (1995) Cambridge

Asheri D., “The Art of Synchronisation in Greek Historiography: the Case of Timaeus of Tauromenium”, Scripta Classica Israelica, 11 (1992) 52-89

Linked Pages: Date of the Foundation of Rome I: Timaeus

Return to Roman Pre-History