Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Dictatorship Clavi Figendi Causa

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Dictatorship Clavi Figendi Causa

Origins of the Dictatorship Clavi Figendi Causa

According to Livy, in the consulship of L. Genucius Aventinensis and Q. Servilius Ahala (365 BC):

“Matters were quiet as regarded domestic troubles or foreign wars, but ... a pestilence broke out ... The most illustrious victim was M. Furius Camillus, whose death, though occurring in ripe old age, was bitterly lamented ... [He] was counted worthy to be named next to Romulus, as the second founder of Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 1: 7-10).

Camillus’ victory at Vell in 396 BC had marked the start of the Roman conquest of Italy, and his death some three decades later must have felt like the end of an era.

The epidemic continued into the following year. Attempts were made to placate the gods, but they proved ineffective: in 363 BC, the Tiber broke its banks and flooded the Circus, an event that was taken as a sign of the gods’ continuing displeasure. According to Livy, at this point:

“Older men are said to have remembered that a pestilence had once been assuaged by the dictator [ritually] fixing a nail. The Senate believed this to be a religious obligation and ordered the appointment of a dictator clavi figendi causa (for the purpose of fixing the nail) ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 4-6).

As Mark Wilson (referenced below, at p. 36) observed, it is not possible to identify the occasion on which this earlier unidentified dictator had been appointed. All we can say is that Livy’s record of the appointment of such a dictator in 363 BC (which, was we shall see, is also found in the fasti Capitolini) is the earliest securely-dated record of its kind in our surviving sources.

Ancient Rite of the ‘Clavus Annalis’

Livy began his account of the dictatorship of 363 BC with a description of the ancient rite of the annual ‘fixing of the nail’:

“There is an ancient law, written in archaic letters, that reads:

‘Let him who is the praetor maximus [the original name of chief magistrates of the Republic] fasten a nail on the Ides of September’.

This notice was fastened up on the right side of the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, next to the ‘temple’ of Minerva. This nail is said to have marked the number of the year (written records being scarce in those days) and was, for that reason, placed under the protection of Minerva, because she was the inventor of numbers”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 5-7).

This is consistent with the definition of the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus, epitomised by Festus :

“The ‘clavus annalis’ [annual nail] was so called because it was fixed into the walls of the [Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus] every year, so that the number of years could be reckoned ...” (‘De verborum significatu’, 49 Lindsay).

Livy explained:

“The consul Horatius established the [ancient] law and dedicated the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in the year following the expulsion of the kings [conventionally 509 BC]”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 5-8).

Henk Versnel (referenced below, at p. 270 ) pointed out that the rite of the clavus annalis was carried out on:

“... the dies natalis [anniversary of the day of dedication] of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, [which was also] the day regarded as the beginning of the Republic, since, according to tradition, M. Horatius, one of the [five men traditionally named as consuls during] the first year after the expulsion of Tarquin, had dedicated the temple [on this day].”

In other words, if this reading of the text of the ancient law is correct, the annual fixing of the nail at the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus had once provided a measure of the number of years that had passed since the start of the Republic and the consecration of the Capitoline temple. Interestingly, a single record of this method of dating survives: according to Pliny the Elder, Cn. Flavius, who was curule aedile in 304 BC built the Temple of Concordia above the Comitium:

“... recorded in an inscription engraved on a bronze tablet that the shrine had been constructed 204 years after the consecration of the Capitoline temple [which, according to tradition, was in 509 BC]”, (‘Natural History’, 33: 6).

Cincius

Livy explained the origins of this ancient practice as follows:

“Cincius, a careful student of records of this kind, asserts that, at [the Etruscan city state of] Volsinii, nails were fastened in the temple of Nortia, an Etruscan goddess, to indicate the number of the year”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 7-8).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below , 1998, at p. 81) observed that this ‘Cincius’ is almost certainly the antiquarian L. Cincius, and that the source is probably the ‘mystagogicon’, which he probably wrote prior to the burning of capitol in 83 BC. He also argued (at p.75) that the information above from both Livy and Festus derived from the same passage of Cincius.

Etruscan Rite of Driving the Nail

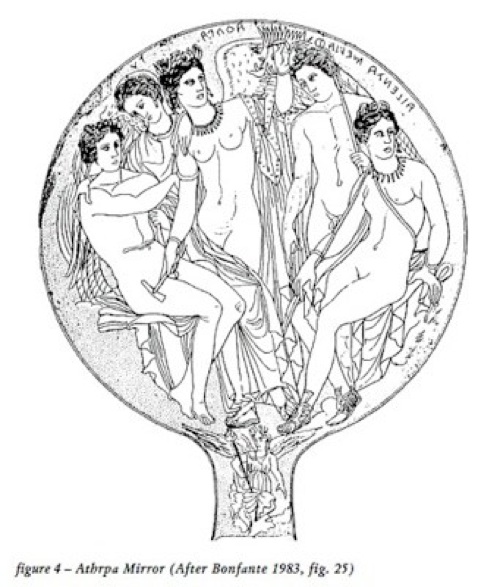

Bronze mirror (late 4th century BC) from Perugia, now in the Berlin Antiquarium

Image from Wayne L. Rupp Jr (referenced below, Figure 4, at p. 213)

Apart from the passage by Cincius discussed above, the only surviving evidence of an Etrucan ritual involving the driving of a nail comes from the mirror illustrated above, in which a goddess identified as Athrpa (Greek Atropos, oldest of the three Moirai, the goddesses of Fate) is about to drive a nail into the head of a boar.

Annalisa Calapà (referenced below, at p. 43) pointed out that Cincius’ record of the similarities between the ritual of the clavus annalis at Rome and at Volsinii:

“ ... suggests that the Etruscan goddess [Nortia] was somehow assimilated to Minerva: this seems to be confirmed by a dedication (AE 1962 0152) to Minerva Nortina found in Visentium, a Roman municipium on the west side of the lake of Bolsena [the site to which the people of Volsinii moved when the Romans destroyed their original city in 264 BC].”

The important point is that there is nothing to suggest that this ancient ritual had anything to do the the propitiation of the gods.

Putative Evolution from the Rite of the Clavus Annalis

Livy presumably started this description of the ancient ritual of fixing the nail to record the passing years because he believed that it had evolved over time into an occasional propitiatory ritual of the kind that the Senate mandated in 363 BC. He then gave a short (an not particularly helpful) summary of how this putative evolution had occurred:

“The ceremony ... had subsequently passed from the consuls to dictators, because they possessed greater authority. Then, after the custom had lapsed, the matter was viewed as worthy in itself to warrant the appointment of a dictator clavi figendi causa (for the purpose of fixing the nail)”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 8)

The occasion prior to 363 BC on which a pestilence had been assuaged by a dictator fixing a nail (which, it was said, the older men of 363 BC remembered) had presumably occurred (or was imagined to have occurred) in ca. 400 BC, by which time the annual rite of a dictator fixing the nail had presumably lapsed.

Francisco Pina Polo (referenced below, at p. 39) observed that:

“Livy understood [the appointment of the dictator clavi figendi causa of 363 BC to be] an attempt at recovering a lost rite:

✴Perhaps this was indeed the case and, maybe, the clavus annalis had ceased to exist, at least from the beginning of the 4th century BC.

✴However, this could [alternatively] be a case of incorrect interpretation on the part of Livy, who may have [believed incorrectly] that the [occasional] appointment of a dictator specifically for fixing the nail [for propitiatory purposes] meant that the annual ritual [for chronological and/or propitiatory purposes] had ceased to exist [by 363 BC].”

Unfortunately, we have no basis upon which to decide between these alternatives and, if Livy had made a mistake, we have no way of knowing when the annual rite was actually abandoned in Rome. All we can say is that it had certainly been abandoned by the time that Livy was writing, since:

✴his account of it relied on Cincius’ record of the archaic inscription in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus; and

✴he seems to have written it for an audience that had never come across it.

However, a few years earlier, Cicero had begun a letter to Atticus as follows:

“I arrived at Laodicea on the 31st of July [51 BC]. From this day, ex hoc die clavum anni movebis (you should move the nail of the year”, (my translation of ‘Letter to Atticus’, 5:15)”.

Here, Cicero suggested that Atticus should measure the year of his (i.e. Cicero’s) stay in Laodicea in the ancient manner. The casual nature of this suggestion indicates that the rite of the clavus annalis was still recalled, at least in some quarters, in the 1st century BC.

Dictator Clavi Figendi Causa of 363 BC

Thus, the earliest surviving records of the appointment of a dictator clavi figendi causa is that of 363 BC: according to Livy, after the Senate had decided on the appointment of a dictator clavi figendi causa:

“... L. Manlius was accordingly nominated, and he appointed L. Pinarius as his master of the horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 8)

This is confirmed by a fragmentary record for this year in the fasti Capitolini, which reads:

“Dictator: [L. Manlius Capitolinus] Imperiosus, magister equitum: [L. Pinarius . . .] Natta: clavi figendi causa”

Livy recorded that Manlius was specifically appointed to hammer in the propitiatory nail, but he did not record that he actually did so: he simply recorded that Manlius:

“... acted as if his had been appointed for military reasons ... He harboured ambitions for war with the Hernici and angered the men liable to serve [in this war] by the oppressive way in which he conducted their conscription. [When he found himself facing] the unanimous resistance of the tribunes of the plebs, he gave way (either voluntarily or through compulsion) and laid down his dictatorship”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 9).

Putative Impeachment of L. Manlius Imperiosus

It seems that Manlius’ resignation:

“.. did not... prevent his impeachment the following year ... The prosecutor was M. Pomponius, one of the tribunes of the plebs”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 4: 1).

Livy claimed that the one of the charges against Manlius was that he had used exceptional brutality in order to conscript men to fight the Hernici. Cicero, who did not record that charge, did record that Manlius had been charged:

“... with having extended the term of his dictatorship a few days beyond its expiration’, (‘De Officiis’, 112).

Both men agreed that, in Cicero’s words:

“He [was] further charged ... with having banished his own son Titus ... from all companionship with his fellow men, [exiling him from Rome and] requiring him to live in the country.”

As I described in my page on Titus Manlius Imperiosus Torquatus, Cicero and Livy both drew on a fanciful story in which, in a fine example of filial piety, the young Titus used the threat of violence against Pomponius to ‘persuade’ him to drop all charges against the ex-dictator.

Dictator Clavi Figendi Causa of 363 BC: Conclusions

There is no obvious reason to doubt that L. Manlius Imperiosus was appointed as dictator clavi figendi causa in 363 BC for the purpose of propitiating the gods. He may subsequently have been been accused by a tribune of the pleb of some sort of violation. It is possible that Livy’s claim that he tried to remain in office in order to secure a role in the anticipated war with the Hernici is correct. However, if so, then he would have averted this danger by his voluntary or enforced resignation: as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 84) observed:

“The historicity of the whole tale [of the prosecution of L. Manlius Imperiosus] is very doubtful ... :

✴it is hard to see how so much detail could have survived from 362 BC to Livy’s time; and

✴[the putative defendant] corresponds so well to the stock character of the Manlii.”

Mark Wilson accepted Manlius’ dictatorship and, on balance, his unsuccessful attempt to extend it and broaden its scope. He observed (at p. 141) that:

“... since he was only in office for a day or two [in order to perform the ritual fixing of the nail], it is clear that, if he was accused in relation to his conduct in office, then he would have been] accused:

✴not of remaining in office beyond some set term; but

✴of remaining in office after he had discharged the duty for which he had been appointed and after which, according to long-established custom, he should have foresworn his imperium and resigned.”

After analysing the scope of the dictatorship in detail pp. 384-5), be concluded (inter alia, at pp. 384-5) that:

“At least during the period of the prevalence of the office during the first three centuries of the Republic, dictators did only what was asked of them by the Senate or the people ... The one ... [potential] exception, [that of L. Manlius Imperiosus in 363 BC], is as much a demonstration of this rule as the otherwise universal adherence to it: he was forced to abandon the war he thought he had a right to fight ... and to resign in disgrace ... [precisely because] no rule relating to the dictatorship [was] more rigorous than adherence to the mandate. ... This rule is so solid that its very solidity becomes a matter of interest.”

Dictator Clavi Figendi Causa of 331 BC

Livy recorded the appointment of another dictator clavi figendi causa in 331 BC, which was:

“A terrible year ... , whether owing to the unseasonable weather or to man's depravity”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 18: 1).

He then reluctantly recorded that the year had witnessed a spate of deaths among the leading citizens of Rome and, while their deaths were originally attributed to an epidemic of some sort, it subsequently became clear that they:

“... were in reality destroyed by poison”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 18: 3).

The truth came to light when:

“... a certain serving woman came to Q. Fabius Maximus, the curule aedile, and declared that she would reveal the cause of the general calamity, if he would give her a pledge that she should not suffer for her testimony. Fabius at once referred the matter to the consuls, and the consuls to the Senate ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 18: 4-6).

This led to an investigation that revealed that some 170 Roman matrons were tried and found guilty of murder.

Livy noted that:

“... there had never before been a trial for poisoning in Rome. [The behaviour of the matrons] was regarded as a prodigy, and suggested madness rather than felonious intent. Accordingly, when a tradition was revived from the annals, which recorded that:

✴in secessions of the plebs, a nail had been driven by the dictator; and

✴how the minds of men who had been driven mad by civil discord had been restored to sanity by that act of atonement;

[the Senate] resolved on the appointment of a dictator to hammer in the nail. The appointment went to Cnaeus Quinctilius, who named L. Valerius master of the horse. The nail was [duly] hammered in and they [then] resigned”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 18: 11-13).

The fasti Capitolini record this dictatorship but disagree with Livy as to the identities of the dictator and his master of horse: they named:

✴Cnaeus Quinctius Capitolinus as dictator clavi figendi causa; with

✴C. Valerius Potitus as his master of horse (after he resigned as consul).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 74) pointed out that:

“Livy’s statement ... that there had been a dictatorship clavi figendi causa during a secession of the plebs is not supported by any other [surviving record of] such an appointment ...”

However, he cited a record by Livy in which:

“The games that had been vowed by the decemviri, in pursuance of a decree of the Senate, on the occasion of the secession of the plebs from the patricians, were performed in [441 BC]”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 12: 2).

He suggested that, since:

“... these games, [which] clearly had an apotropaic purpose, were performed after civil disturbance, ... it is perhaps possible that a ritual nail was also fixed [in such circumstances].”

Dictator Clavi Figendi Causa of 313 BC (?)

The situation in 313 BC is more complicated. Both Livy (‘History of Rome’, 9: 28: 1-2) and the fasti Capitolini record that the consuls for 313 BC were:

✴L. Papirius Cursor was now serving for the fifth time; and

✴C. Junius Bubulcus Brutus for the second time.

A number of sources suggest that a dictator was also appointed in this year, although there is some divergence as to his function:

✴the fasti Capitolini describe him as a dictator rei gerundae caussa (for the purpose of conducting affairs) and both Livy (in his preferred version of events) and Diodorus have him exercising military command at this point in the Second Samnite War; while

✴other sources known to Livy recorded that the consuls appointed this dictator

... on the outbreak of a pestilence in order to drive the nail”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 28: 6)

Furthermore:

✴Livy and the fasti Capitolini identified him as C. Poetelius Visolus; while

✴Diodorus identified him as Q. Fabius Maximus Rullianus.

Taking the easiest discrepancy first, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 332) is surely correct that:

“... [Diodorus’] alleged dictatorship of Fabius Rullianus ... is very suspect ...”

Poetelius was almost certainly appointed as dictator in 313 BC, but his precise role needs to be addressed.

Mark Wilson (referenced below, at p. 545, entry 54) observed that:

“Unusually, this dictatorship came, not in the wake of a crisis or disaster, but [in the wake of] a great victory won the previous year by the consuls [of 314 BC]. Nevertheless, according to Livy’s preferred sources, the consuls for 313 BC appointed] a dictator to [continue the prosecution] of the war...”

He also noted that later tradition had Poetelius as ‘dictator clavi figendi causa‘ in 313 BC. Stephen Oakley (as above) pointed out that the appointment of a dictator ‘clavi figendi causa’ was unusual, which makes it more likely that this was, indeed the post assigned to Poetilius in 313 BC. Finally, Mark Wilson (referenced below, at pp. 327-8) observed that:

“To accept [Poetelius as as ‘dictator clavi figendi causa’] makes sense of the otherwise mysterious decision to appoint an inexperienced dictator over very experienced consuls to fight ... the Samnites ” (my slightly changed word order).

Dictator Clavi Figendi Causa of 263 BC

The fasti Capitolini record the appointment of Cnaeus Maximus Centumalus as dictator clavi figendi causa in 263 BC, at the start of the First Punic War: the reason for this appointment is unknown because Livy’s narrative for this period no longer survives and the appointment is not mentioned in any of surviving source.

[In construction]

Mark Wilson (referenced below, at pp. 476-480) surveyed the way in which the Romans tried to appease and propitiate the gods in time of crisis changed over time. He concluded (at p. 480) that:

“... by the time of the social watershed of the 370s and 360s, the dictatorship was being adapted to specialised roles, including being a reusable, systematic way of signalling special priority in an act of mediation with the gods. By the 3rd century, however, a more regular process was developing through the traditional resort to the Sibylline Books: the Senate watched for moments of need; they called upon the decemviri to consult the books; they then directed the implementation of their recommendations ..., and propitiation was often undertaken by the people as a whole through collective prayers, festivals, and other organised, communal, public events rather than through the actions of magistrates on their behalf.”

There is, however, one intriguing aspect of the information presented above that might indicate an continuing association between the driving of the nail and the counting of years: the dates three out of the four records above (363, 313 and 263 BC) indicated an underlying 50 year cycle for the appointment of a dictator clavi figendi causa.

Mark Wilson (referenced below, at p. 31)

“The dictatorships clavi figendi causa were motivated by the stated desire to have the propitiation [of the gods]conducted by the magistrate with the highest possible imperium, in order to show the utmost respect for the divine; this dictatorship represented an escalation above the consuls, who were present and might otherwise have performed this deed. The main difference between [the dictator clavi figendi causa appointed] in 363 BC and possible earlier nail-drivers was that, in this case, there was no coincident military threat.”

In other words, it is possible that, when the need to propitiate the gods arose during a year in which a dictator was already in place to deal with a military threat, he would also have been called on to drive the ritual nail.

Read more:

Wilson M., "The Needed Man: Evolution, Abandonment, and Resurrection of the Roman Dictatorship" (2017) thesis of City University of New York

Feeney D., “Fathers and Sons: the Manlii Torquati and Family Continuity in Catullus and Horace”,

in Kraus C., Marincola J. and Pelling C. (editors), “Ancient Historiography and its Contexts”, (2010) Oxford, at pp. 205-23

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume III: BookIX”, (2005) Oxford

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume II: Books VII and VIII”, (1998) Oxford

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)