Early Argead Rulers of Macedonia

Alexander I (ca. 500 - 450 BC):

Alexander and the Persians III: Persian War

Early Argead Rulers of Macedonia

Alexander I (ca. 500 - 450 BC):

Alexander and the Persians III: Persian War

IN CONSTRUCTION

Image from Wikipedia (my additions in blue)

Hellenes’ Preparations for War

In this and the following section, I will go back in time to see how Herodotus described the Hellenes’ various responses, once they became aware of Xerxes’ aggressive intentions.

Themistocles, the Athenian Fleet and the Silver Mine at Laurium

According to Herodotus, the Athenians were the first to prepare to oppose Xerxes’ imminent invasion: he noted that:

“The revenues from the mines at Laurium [in southern Attica] had brought great wealth into the Athenians' treasury, and each man was about to receive 10 drachms for his share. However, [the leading statesman] Themistocles persuaded the Athenians ... to use the money instead to build 200 ships for ... the war with Aegina. It was, in fact, the outbreak of this war that saved Hellas by compelling the Athenians to become seamen: [as things turned out], the ships were not used for ... [the war with Aegina, but they were available] for the Athenians' to use [in 480 BC, albeit that] they had to build others besides”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 144: 1-2).

A passage by Aristotle probably provides more detail about these events: he recorded that:

“... in the archonship of Nicomedes [483 BC], following the discovery of the [silver] mines at Maronea, the working of which had given the state a profit of 100 talents, some advised that the money should be distributed among the people; but Themistocles prevented this, not saying what use he would make of the money, but recommending that it should be lent to the 100 richest Athenians, each receiving a talent, on the basis that:

✴if they spent it in a satisfactory manner, the State would have the advantage [and the loan would presumably be written off]; but

✴if they did not, the State would call in the loan.

On these terms the money was put at [Themistocles’] disposal, and he used it to finance a fleet of 100 triremes, with the 100 ‘borrowers’ building one each. [The Athenians] fought the naval battle at Salamis [see below] against the [Persians] with these triremes”, (‘Athenian Constitution’, 22: 7).

As Anthony Vivian (referenced below, at pp. 68-9) pointed out, although there are some discrepancies between these two accounts, they clearly relate to the same event: Vivian argued that:

✴Aristotle’s ‘Maronea’ was almost certainly the same place as Herodotus’ Laurium; and

✴Aristotle’s figure of 100 (rather than Herodotus’ 200) ships is likely to be the correct figure, since (for example) Herodotus recorded (at ‘Persian Wars’, 8: 1) that the Athenians provided 127 ships for the allied fleet at Artemesium in 480 BC (see below).

We can reasonably assume that the famously wily Themistocles had drawn the obvious conclusion from the Persians’ engineering activity at Acanthus and Eion, and that it was this that prompted him to use the windfall from Laurium for shipbuilding (and, presumably, for the training of the sailors who would man the ships).

Colin Kraay (referenced below, at pp. 57-8) observed that Themistocles’ shipbuilding programme:

“... would have required considerable supplies of timber and other materials from abroad; the silver was [now] available to pay for them, and its conversion into coin should be detectable in a sharply increased number of dies. ... It is ... clear that the late unwreathed [owl tetradrachm issued by the Athenians] were very much larger than the early wreathed ones, [and were presumably] the result of the new discoveries of silver that financed [Themistocles’] ship-building programme. Their low artistic quality must be attributed to the urgency with which the coins were required; ...”

As we shall see, Herodotus recorded taht Alexander was a proxenos and euergetes (diplomatic ‘friend’ and benefactor) of Athens by 479 BC, and it is possible that he had earned this honour by supplying the Athenians with some of the timber for Themistocles’ ships.

Xerxes’ Pre-emptive Demands for the Submission of the Hellenes

According to Herodotus, in 481 BC, when Xerxes arrived at Sardis at the start of the winter of 481/0 BC, he:

“... sent heralds to Hellas to demand earth and water and to command that feasts should be prepared [in readiness for his imminent arrival]: ... The reason for his [repeating Darius’ earlier] demands for earth and water was that he fully believed that those who had refused to submit to Darius would now submit to him through fear”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 32).

He later recorded that, while Xerxes was at Pieria (in Macedonia - see below):

“... the heralds whom Xerxes had sent to Hellas to demand earth and water returned, some empty-handed but some bearing earth and water”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 131).

He then:

✴recorded the names of the Hellenes who had sent earth and water (at ‘Persian Wars’, 7: 132: 1 - see below); and

✴explained (at ‘Persian Wars’, 7: 132-3) that Xerxes had not sent heralds to either Athens or Sparta, claiming that this was because each of them had killed the herald that Darius had sent to them in similar circumstances a decade before (although this was the first time that Herodotus had mentioned this earlier sacrilege).

The effect of Xerxes’ initiative would have been to highlight the fact that the other Greek poleis would have to choose sides, and it seems that, by the time that Xerxes reached Pieria, at least some of them had chosen the side of Xerxes.

Formation of a Panhellenic Anti-Persian League (?)

Herodotus seems to have assumed that the Athenians also assembled like-minded poleis in order to form an anti-Persian alliance. However, this has to be established from a number of separate passages:

✴Having listed the Hellenes who had submitted to Xerxes, Herodotus recorded that:

“Against all of these, the Hellenes who were undertaking the war against [Xerxes] swore a solemn oath, [to the effect that], if the should emerge victorious, they would make all those who had voluntarily submitted to [Xerxes] pay dekate (a tithe or tenth) to the god of Delphi”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 132: 2).

This is an oddly-placed passage, in which the Hellenes who swore this oath were not identified.

✴At the end of his account of Themistocles’ expansion of the Athenian fleet, Herodotus recorded that the Athenians:

“... resolved that they would put their trust in Heaven and oppose [Xerxes] with the whole power of their fleet ... , and with all other Hellenes that were so-minded”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 144: 3).

This suggests that the Athenians intended to use their new fleet in concert with other like-minded poleis, who=ich would presumably supply a land army.

✴After a short and inconsequential sentence, he continued:

“All the Hellenes who were most concerned for the welfare of Hellas gathered together, conferred with each other and exchanged vows. They resolved in debate to make an end of all their feuds and wars against each other ...”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 145: 1).

✴In a subsequent passage, he referred to these particular Hellenes as those:

“... συνωμόται [meaning those allied by oath] against the Persians ...”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 148).

Taking this and the previous passage together, we now have a group of like-minded Hellenes (which had presumably included Athens) that had sworn to act in concert to oppose Xerxes.. This was presumably the same group who had sworn to tithe those Hellenes who voluntarily submitted to him.

✴He then recorded that, shortly after the meeting described at 7: 145: 1 (above) the newly-sworn allies:

“... learning that Xerxes was at Sardis with his army, resolved:

•to send spies into Asia to find out what [Xerxes] was doing; and

•to despatch messengers to Argos, in an attempt to make the Argives their allies against [Xerxes]; and

•also:

-to Gelon son of Dinomenes, [king of Syracuse] in Sicily;

-to Corcyra, [modern Corsica]; and

-to Crete;

urging them all to come to the aid of Hellas”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 145: 2).

All of this is surprisingly vague: all we know so far is that a group of ‘Hellenes who were most concerned for the welfare of Hellas’ had sworn to oppose Xerxes’ imminent invasion, and that, to this end, they also acted in concert in:

✴threatening those Hellenes who voluntarily submitted to Xerxes;

✴sending men to Sardis to spy on Xerxes’ preparations for war; and

✴soliciting the allegiance of Argos, Syracuse, Corcyra and Crete.

Herodotus did not address the proposed command structure of the alliance and he did not specify where its meetings were held.

We learn a little more about the alliance (as Herodotus conceived it) from his imaginary account of the embassy to Gelon:

✴the envoys sent to Gelon included a Spartan named Syagrus (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 153);

✴on their arrival, these envoys announced that:

“The [Spartans] and their allies have sent us secure your help against [Xerxes], who, as you know, [is about to march into] Hellas ... ”, ‘Persian Wars’, 7: 157); and

✴when Gelon demanded overall command of the pan-hellenic army or, if not, then of its fleet:

•Syagrus countered that:

“Agamemnon son of Pelops would turn in his grave if he heard that the Spartans had been deprived of their command by Gelon and his Syracusans! No, put the thought out of your head ... If you want to come to the aid of Hellas, you must understand that you will be under the command of the [Spartans]”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 159); and

•the (unnamed) Athenian envoy added that:

“Even if the [Spartans] should permit you to command [the fleet], we would not do so: this command (which the [Spartans] do not want for themselves) is ours, ... [not least] because:

-we possess the greatest number of seafaring men in Hellas ...’ [and]

-as the poet Homer says, it was [Menestheus, King of Athens] who was pre-eminent among the men who came to Troy in [the art of] ordering and marshalling armies”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 161: 2 - 3).

Thus, Herodotus implicitly assumed that, by this time, it had been agreed that:

✴Sparta would naturally exercise overall command of its combined forces as hegemon; and

✴Athens, acting under Spartan hegemony, would naturally exercise overall command of its combined fleet.

As things turned out, the spies they sent to Asia were apprehended and killed, and their attempts to persuade Argos, Syracuse, Corcyra and Crete to join their alliance all failed. Futhermore, as we shall see, the Spartans actually commanded both the fleet and the land army.

We should now look at the parallel passages in the much later work of Diodorus Siculus (who would have relied on Herodotus but also on other sources. Unfortunately, only fragments of his Book 10 survive, although he began his Book 11 by noting that it had:

“... ended with:

✴the events of [481 BC], immediately prior to Xerxes’ crossing into Europe; and

✴the speeches delivered in to koinon ton Hellenon synedrion (the common council of the Hellenes) that was held in Corinth about [the proposed] alliance between Gelon and the Greeks”, (‘Library of History’, 11: 1).

Thus, in Book 10, Diodorus had recorded that, in 481 BC, a number of the poleis of Hellas had formed a standing anti-Persian alliance that met at Corinth (which would mean at the sanctuary of Poseidon at the Isthmus of Corinth and imply Spartan hegemony). Interestingly,in his passage in Book 11 that parallels Herodotus 7: 132: 2, Diodorus recorded that:

“... the Hellenes who were in joint session at the Isthmus [of Corinth] resolved to make those Hellenes who had voluntarily chosen the cause of the Persians pay a tithe to the gods, should they [i.e., the allies] emerge victorious”, (‘Library of History’, 11: 3: 3).

On the basis of this disjointed body of evidence, all we can really conclude is that the Spartans and the Athenians both resolved to confront Xerxes as soon as they became aware of his intentions, and that they probably agreed, at least initially:

✴to co-ordinate their actions against him; and

✴to attract or coerce as many other Hellenic poleis as possible to the cause of Hellas, although they were only partially successful in these endeavours.

It will soon become clear that the Spartans were in overall command of the entire operation, albeit that the Athenians made an important contribution to the part played by the Hellenic fleet.

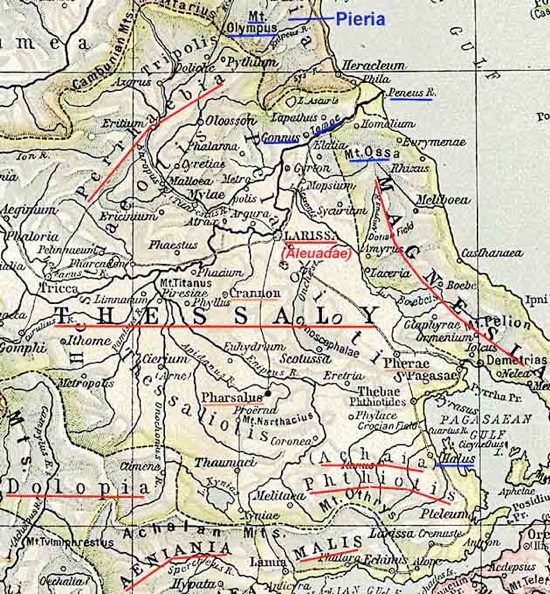

Xerxes and the Thessalians

Image adapted from this page in Wikipedia

My additions: Blue = places mentioned by Herodotus (above)

Red = places that sent earth and water to Xerxes (see below)

Brown (Pherae, Pharsalus and Crannon) = poleis that were traditionally opposed to the Aleuadae of Larissa

Herodotus recorded that, soon after Xerxes succeeded to the Persian throne, he received messengers:

“... from the Aleuadae, inviting him into Hellas with all earnestness; and the Peisistratidae, who [were exiled from Athens] came to Susa with the same pleas as the Aleuadae and offered Xerxes even more than they did”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 6: 2).

The Aleuadae were the rulers of Larissa and, at this time, the most powerful family in Thessaly, although other Thessalian poleis such as Pherae, Pharsalus and Crannon had their own ruling families, and it is possible that they calculated that submission to Xerxes would bolster their political power over their neighbours.

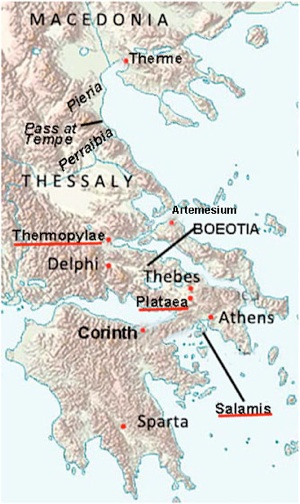

Hellenes’ Presence in Thessaly: Xerxes at the Hellespont

In a passage that (as we shall see) came in the wrong place in chronological terms, Herodotus explained that:

“The Thessalians had at first taken the Persian part unwillingly and of necessity, since they made it clear that they disliked the intrigues of the Aleuadae: thus, as soon as they heard that [Xerxes] was about to cross over into Europe, they sent envoys to the Isthmus [of Corinth], where representatives of Hellas (who had been chosen by the poleis that were most concerned for the welfare of Hellas) were assembled. The Thessalian messengers addressed them as follows:

‘Men of Hellas, the pass of Olympus must be defended, so that Thessaly and all Hellas may be sheltered from this war. Now, we are ready to guard it with you, but you too must send a large army; if you will not, then you should know that we will [be forced to] submit to [Xerxes] ...’

Thus spoke the men of Thessaly”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 172” 1-3).

These messengers were presumably sent by a Thessalian faction who were opposed to the Aleuadae. Herodotus then recorded that:

“In response, the Hellenes resolved that they would send an army to Thessaly by sea to guard the pass. When the forces had assembled, they ... disembarked [at Halus, on the Pagasean Gulf, which probably belonged to Pherae] and took the road for Thessaly, leaving their ships where they were, They then came to the pass of Tempe, which runs from the lower Macedonia into Thessaly along the river Peneus, between the mountains Olympus and Ossa. The army that established their camp their was made up of:

✴about 10,000 foot soldiers; and

✴the Thessalian cavalry.

[As for the command structure]:

✴the general of the [Spartans] was Euaenetus son of Carenus, who was chosen from among the Polemarchs [i.e., the Spartan regimental commanders], but he was not of the royal house; and

✴the commander of the Athenians was Themistocles, son of Neocles”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 173).

It was at this point that Herodotus had first identified Alexander as a participant in Xerxes’ campaign: he recorded that this Greek force remained at the pass:

“...for only a few days, for messengers came from Alexander son of Amyntas, the Macedonian, pointing out the great size of [Xerxes’] army and the great number of his ships and advising them to withdraw and thereby avoid being crushed by the invading host. The Hellenes recognised that this was good advice and, since it indicated that [Alexander] meant well by them, they took it. ... The Hellenes accordingly returned to their ships and sailed back to [Corinth]”, (‘Persian Wars’ 7: 173).

Herodotus himself was not convinced by this story, which he might well have heard from Alexander: he noted that:

“In my opinion, what really convinced [the Greeks] was fear [of being out-flanked], since they had found out that there was another pass leading into Thessaly by the hill country of Macedonia through Perraebia, near the town of Gonnus, and this was the way by which Xerxes' army actually did descended on Thessaly”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 173).

Herodotus ended this account by observing that:

“This was [the Hellenes’] expedition to Thessaly, while Xerxes was planning to cross into Europe from Asia and was already at Abydos. The Thessalians, now deserted by their allies, adopted Xerxes’ cause without hesitationand with so much zeal that they proved themselves most useful to [Xerxes] in the war [that followed]”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 174).

Xerxes at Therme

According to Herodotus, when Xerxes had established his base at Therme (see above), he undertook naval reconnaissance of the coast of Thessaly and, in particular, of the mouth of the river Peneius, which flowed through a gorge between mountains of Olympus and of Osssa (see the map above). On seeing it, he:

“... asked his guides if there were any other outlet for the Peneus river into the sea, ... [and they assured him that there was not]. On hearing this, Xerxes said:

‘These Thessalians are wise men: ... [their geographical position explains their early submission]. It would only have been necessary ... [for me to dam the river, cutting it off from the sea] for the whole of Thessaly, with the exception of the mountains, to be under water.‘

In making this remark, Xerxes was referring to the sons of Aleues, who were the first Greeks to surrender themselves to him. [Furthermore], he assumed that, when they offered him friendship, they spoke for the whole of Thessaly. After delivering this speech and seeing what he had come to see, he sailed back to Therme”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 130: 1-3).

Xerxes at Pieria

Herodotus then noted that Xerxes moved his army from Therme of Pieria, on the southern boundary of Alexander’s territory and the northern border of Hellas: so far, he had been on territory that was familiar, at least to Mardonius, but he was now about to move into unknown territory. Thus, as Herodotus reported, he:

“... lingered at Pieria while a third of his army cleared a road over the Macedonian mountains so that the whole army might pass by that way to Perraibia, [one of the Thessalian perioicoi]”, (‘Persian Wars’’, 7: 131).

He then recorded that, while these military preparations underway:

“... the heralds whom Xerxes had sent to Hellas to demand earth and water returned, some empty-handed but some bearing earth and water”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 131).

He noted the names of the Hellenes who had submitted by sending him ‘earth and water’ (at ‘‘Persian Wars’, 7: 132: 1), which can be split into two groups:

✴a northern group that included the Thessalians and their neighbours: the Dolopians; the Aenians; the Perraebians; the Magnesians; the Malians; and the Achaeans of Phthiotis (see the map above); and

✴a more southerly group that included: the Locrians; the Thebans; and all the Boeotians except Thespians and the Plataeans (see below).

Finally (at ‘Persian Wars’, 7: 185), he listed the European ‘nations’ that contributed to Xerxes’ army, which again can be split into two groups:

✴those from the northern Aegean included: Thracians; Paeonians; Eordi; Bottiaei; Chalcidians; Brygi; Pierians; and Macedonians: and

✴those from Thessaly included: Perraebians; Aenians; Dolopians; Magnesians; and Achaeans of Phthiotis.

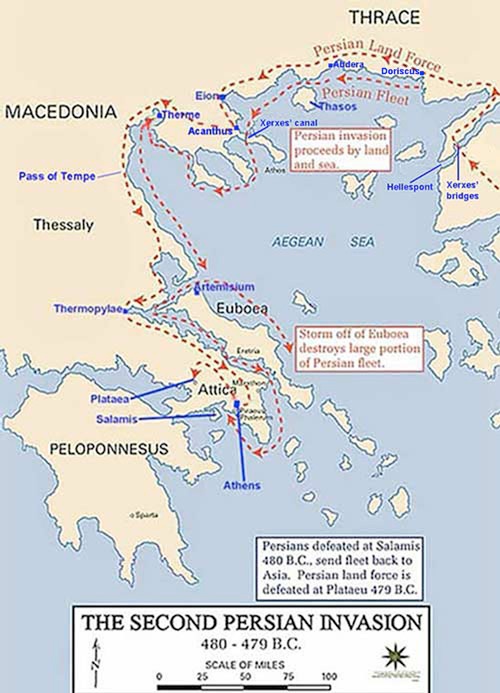

Battle of Thermopylae

Image adapted from the website Iran and the Iranians

Herodotus recorded that, at a meeting at Corinth, the Hellenic allies decided that:

“... in view of what Alexander had told them, ... they should [make their stand] at the pass of Thermopylae ... They [therefore] resolved:

✴to guard this pass in an attempt to keep [Xerxes’ army] out of Hellas; and

✴to send their fleet to [the nearby port of] Artemisium ... , so that their land and naval forces [could easily co-ordinate their operations]”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 175: 1-2).

The main task of the fleet was protect the flank of the Hellenes at Thermopylae from the attentions of Xerxes’ navy. Herodotus then recorded that:

“... hearing that [Xerxes] was in Pieria, [the Hellenes] dispersed [were dismissed?] from their meeting at the Isthmus and set out to do battle, some traveling on foot to Thermopylae, and others by sea to Artemisium”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 177).

David Yates (referenced below, at p. 4) argued that:

“This brief notice leaves little room to imagine a standing [Hellenic] Council in session at Corinth during the subsequent campaign season. Moreover, neither Herodotus nor Thucydides mentions any further meetings of a Panhellenic deliberative body except the war Councils in the field. The common Council, despite manifest importance in 481 BC and the early months of 480 BC, does not remain a permanent feature of the League in the early tradition.”

Interestingly, all that Herodotus initially said about the command structure of the Hellenic forces was that:

“Each city had its own general, but the one most admired and the leader of the whole army was a [Spartan], Leonidas, [at which point, Herodotus set out his Agiad lineage back to Hercules]. He had gained the kingship at Sparta unexpectedly”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 204: 1).

However, after his account of the land battles at Thermopylae, he recorded (‘‘Persian Wars’, 8: 1-3) that:

✴the Athenians supplied 127 of the 271 ships of the Hellenic fleet at Artemesium(although the Plataeans contributed to their manpower);

✴the admiral was the Spartan Eurybiades, son of Euryclides; and

✴there had been talk in the early days of the League of appointing an Athenian to this position but, since the other allies had resisted this, the Athenians had given way.

Diodorus (who believed that the League remained in existence) claimed that:

“The overall commander of [the Hellenic forces] was the Spartan Eurybiades, and the commander of the troops sent to Thermopylae was Leonidas, [one of the two kings] of the Spartans ...”, (‘Library of History’, 11: 4: 1-2).

He subsequently noted that:

“The [Hellenic fleet], which was stationed at Artemisium in Euboea, had 280 triremes (of which 140 were Athenian ...). Their admiral was Eurybiades ... , although Themistocles of Athens supervised the affairs of the fleet ...”, (‘Library of History’, 11: 12: 4).

It is hard to escape the impression that, whatever the formal arrangements, the Spartans dominated the Hellenic war effort, albeit that Themistocles was probably allowed an important supporting role, not least because he had been the driving force behind the building of the Athenian fleet. The detailed events of the battle that followed are probably unrecoverable (see, for example, James Evans, Nicholas Hammond and/or Michael Flower, all referenced below). In summary, it seems that:

✴a small forces under the command of the Spartan King Leonidas defended the pass Thermopylae against Xerxes’ much larger army;

✴he delegated the defence of the alternative pass into Boeotia (which was slightly inland) to the Phocians;

✴the fleet at Artesium successfully prevented the Persians launching an attack on Leonidas from the rear;

✴however, Xerxes’ men easily stormed past the Phocians and cut off Leonidas’ only means of escape, so he had no alternative but to advance on Xerxes’ main army.

What everyone remembered about this battle was the heroic part played by Leonidas. Herodotus recorded that he:

“... came to Thermopylae with the 300 men that he had chosen himself, all of whom had sons [who could continue their line, should they not survive]. He also brought [400] Thebans ... , whose general was Leontiades son of Eurymachus”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 205: 2).

This second sentence is odd since, as we have seen, Herodotus had recorded (at ‘Persian Wars’, 7: 132: 1) that the Thebans (along with the Locrians and all the Boeotians except Thespians and the Plataeans) had already submitted to Xerxes by this time. Herodotus resolved this by claiming that Leonidas had coerced the Thebans into ‘doing their bit’. He then recorded that, when the Hellenes realised that Xerxes had outflanked them, and that most of his army was on its way south, they:

“... took counsel, but their opinions were divided. Some advised not to leave their post, but others spoke against them. They eventually parted, some departing and dispersing each to their own cities, others preparing to remain there with Leonidas”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 219: 2).

In fact, it was probably essential that Leonidas should hold the pass, in order to buy time for the bulk of the Hellenic army to retreat and regroup. According to Herodotus, once the bulk of the army had withdrawn:

“... only the Thespians and Thebans remained [with Leonidas and his 300 men]:

✴the Thebans [under Leontiades] remained against their will, since Leonidas kept them as hostages; while

✴the Thespians, who were commanded by Demophilus, son of Diadromes, gladly remained, ... [promising that] they would stay and die with them”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 222).

Herodotus recorded that, during this final battle:

“Leonidas ... fell, alongside the other [300] Spartans, whose names I have learned by inquiry since they were worthy men”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 227).

It seems that all of the Thespians also died, since Herodotus, having named the three most valiant Spartans who had died alongside Leonidas, recorded that:

“The Thespian who gained most renown [in the last stand] was Dithyrambus, son of Harmatides”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 224).

This brings us to Leontiades and the other 400 Thebans: according to Herodotus, they continued to fight alongside Leonidas:

“... as long as they were ... under compulsion. When, however, they saw the Persian side prevailing and the Greeks under Leonidas hurrying toward the hill [on which they would all be killed], they split off and surrendered to the Persians. With the most truthful words ever spoken, they explained that: ... they had been among the first to give earth and water to Xerxes; they had come to Thermopylae under constraint; and they were guiltless of the harm done to Xerxes. ... [The] Thessalians [in Xerxes’ army] confirmed the truth of their words, but they were not completely lucky: ... the Persians had killed some of them as they approached and most of the rest were branded with the king’s mark on Xerxes’ orders ... , starting with their general, Leontiades”, (Persian Wars, 7: 233: 1-2).

Most scholars reject this account of the Thebans’ forced participation in the battle as patently absurd, and many (see, for example, William Shepherd, referenced below, at p. 337) prefer the later account of Diodorus Siculus, in which Leonidas’ army at Thermopylae included:

“... some 400 Thebans of the [anti-Persian] faction; for there were deep divisions among the inhabitants of Thebes on the matter of the alliance with the Persians”, (‘Library of History’, 11: 4: 7).

In short, by the time of Thermopylae (probably August 480 BC) , although a small Theban faction fought for the Hellenes, Thebes itself was already securely on Xerxes’ side.

; and

since numbers now counted, Leonidas could only put off his own slaughter and that of all the men holding the pass for long enough to allow thePeloponnesian contingents to withdraw and defend the Isthmus, allowing Xerxes to march into Boeotia unopposed

Battle of Salamis

According to Herodotus, having outflanked the Hellenes at Thermopylae:

“The greater and stronger part of [Xerxes’] army marched with Xerxes himself towards Athens and broke into the territory of Orchomenus in Boeotia. Now the whole population of Boeotia took the Persian side, and men of Macedonia sent by Alexander safeguarded their towns, ... [so that Xerxes could see that the Boeotians were indeed taking the Persians’ side”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 34).

The suggests that Alexander had been sent men ahead to check that the Boeotians still honoured the commitment that they had given to Xerxes, and that Xerxes and his army would realise that was the case. Meanwhile, Herodotus noted that, since the Hellenic fleet was no longer needed at Artemisium, it sailed to Salamis at the Athenians’ request, so that they could:

“... evacuate their women and children from Attica ... [since] the Peloponnesians were building a wall at the Isthmus and making the defence of the Peloponnese their top priority”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 40).

Most of the fleet proceeded to Salamis, while:

“... the Athenians docked at their own port. Once there, they made a proclamation that every Athenian should save his children and his household as best he could. Most of them sent their households to Troezen, although some sent them to Aegina and others to Salamis”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 41).

Xerxes now marched on the ghost town that was Athens and, when its few remaining defenders saw that his army had managed to enter the acropolis:

“... some threw themselves off the wall and were killed and others fled into the megaron (probably an inner shrine). ... When [the Persians] had levelled everything, they plundered the sacred precinct and set fire to the entire acropolis”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 53).

He then concentrated his entire fleet at Phaleron, the port of Athens (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 67).

Meanwhile, the Hellenic fleet assembled at Salamis:

“Their commander was [continued to be] Eurybiades son of Euryclides, a Spartan, but not of the royal blood, However, it was the Athenians who furnished by far the most (and the sea‑worthy) ships”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 42).

With the two fleets only 16 km apart and although the Persian fleet was still the larger of the two, the Hellenic fleet occupied the more easily defended position. Once again, the actual course of the sea battle is probably unrecoverable: it was certainly fought at Salamis, and the Hellenes certainly had the better of the fighting, after which:

“The surviving Persians ships fled to Phalerum and took refuge with the land army”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 92).

Meanwhile:

“The Hellenes towed to Salamis all the wrecks that were still afloat in those waters, and prepared for another battle, thinking that [Xerxes] would return with his surviving ships”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 96).

However, it seems that Xerxes decided to cut his losses at this point: Herodotus (at ‘Persian Wars’, 8: 97) ventured that he was afraid that the Hellenes would destroy the bridges at the Hellespont, leaving him trapped in Europe. This prompted Mardonius (who probably expected to take the blame) to make the following suggestion:

“Do not, O king, make the Persians the laughing-stock of Hellas ... [If] you are resolved not to remain [in Europe], march homewards with the greater part of your army. ... [leaving me] to enslave and deliver Hellas to you with 300,000 of your men whom I will choose”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 100: 4-5).

Xerxes duly dispatched what remained of his fleet to secure the Hellespont and began his long march home.

Xerxes’ Return March to the Hellespont

Mardonius escorted Xerxes back to Thessaly, where he established his winter quarters and selected the 300,000 soldiers who were to remain with him in Europe (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 113). He noted (at Persian Wars’ 8: 115) that Xerxes reached the Hellespont in 45 days (although his report of the hardship suffered by his allegedly feeble soldiers is unlikely to be true).

After the battle of Salamis (480 B.C.) Artabazus accompanied Xerxes to the Hellespont with 60,000 men.

Then he returned to Chalcidice and besieged Potidaea and Olynthus, which were in revolt against the Persian rule, and prevented the rebellion from spreading further.

He took Olynthus, but failed to capture Potidaea, called off the siege and joined Mardonius in Thessaly.

He advised Mardonius to abstain from the battle of Plataea and to retire to Thebes, where the Persians would have ample supplies for themselves and their horses and from where they could bribe Greek leaders with the help of gold. When Mardonius perished at Plataea (479 B.C.) Artabazus retired with 40,000 men to Phocis, then via Byzantium to the Hellespont. In 477 he was appointed satrap of Hellespont Phrygia and founded there a hereditary line of satraps. Xerxes selected him as the chief Persian expert on Western affairs to conduct the negotiations with Pausanias of Sparta (477-76). In 450 he defended Cyprus with 300 Phoenician ships and troops under the command of Megabyzus against Cimon, Athenian general. The same year he communicated to Athens that Artaxerxes I wanted to negotiate with them. As a result the “peace of Callias” was concluded, ending hostilities between Athens and Persia.

Diodorus 11.44.4 and 12.4;

Herodotus 8.126-29; 9.41, 42, 58, 66, 89;

Thucydides 1.129-132

Battle of Plataea (479 BC)

With Xerxes’ According to Herodotus (at ‘Persian Wars’, 8: 126), the Persians abandoned Attica and Mardonius spent the winter in Thessaly and Macedonia. He also recorded that Mardonius sent Alexander to the Athenians in what proved to be an unsuccessful attempt to persuade them to change sides:

“He sent Alexander:

✴partly because ... Bubares, a Persian, had married Gygaea (Alexander's sister and Amyntas' daughter, who had given Bubares [a son], Amyntas of Asia, ... to whom the king gave Alabanda, a great city in Phrygia for his dwelling); and

✴partly because he learned that Alexander was proxenos (official trusted friend) and benefactor to the Athenians”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 136).

When Mardonius learned from Alexander that the Athenians had rejected his advances, he marched south, intent upon re-taking Athens. Herodotus observed that”

“The leading men of Thessaly did not repent of [their earlier decision to support the Persians] and were readier than before to further [Mardonius’] march. Thorax of Larissa, who had given Xerxes safe-conduct in his flight, now openly [facilitated his] advance into Hellas”, (‘Persian Wars’, 9: 1: 1).

However, since the Spartans realised that the Athenians might surrender to Mardonius, who would then be able to make use of the Athenian navy, they re-assembled the Greek allies in Attica. Mardonius retreated towards Thebes, and the two armies finally faced each other at Plataea. Herodouts (at ‘Persian Wars’, 9: 31) recorded that the Macedonians fought in the Persian ranks, and that Mardonius positioned them facing the Athenians. He also recorded that Alexander secretly approached the Athenians at night and informed them the Mardonius would probably open the attack on the following day:

“I therefore urge you to prepare, and if (as may be) Mardonius should delay and not attack, wait patiently where you are; for he has but a few days' provisions left. If, however, this war ends as you wish, then you must take steps to save me too from slavery, since I have done so desperate a deed as this for the sake of Hellas ... I who speaks am Alexander the Macedonian”, (‘Persian Wars’, 9: 45).

On the following day, the Greeks won a decisive victory; Mardonius died in the battle and another general, Artabazos, led the Persian retreat: like Xerxes before him, he was keen to rech the Hellespont before the Athenian navt could block his passage. The immediate fate of Alexander (who might well have invented the story of his night visit to the Athenians in order to avoid the consequences of having chosen the losing side) is unrecorded: he presumably marched with Artabazos, who, according to Herodotus:

“... lead his army away straight towards Thrace through Thessaly and Macedonia without any delay, following the shortest inland road. So he came to Byzantium, but he left behind many of his army who had been cut down by the Thracians or overcome by hunger and weariness. From Byzantium, he crossed over in boats ... [and] returned to Asia”, (‘Persian Wars’, 9: 89).

It is possible that Alexander overtly changed sides at this point, and that he was among the ‘Thracians’ who harassed the retreating Persians. The evidence for this is related to a golden statue that Alexander dedicated at Delphi after Plataea:

✴Herodotus recorded that, after their victory at Salamis and their subsequent sack of Carystus :

•the Greek allies returned to Salamis, where they:

“... set apart from their spoils, akrothinia (first offerings) for the gods, [which included three Phoenician triremes that they sent to three different sanctuaries]. After that, they divided the spoils and sent off akrothinia to Delphi, from which was made an andrias (statue of a male figure, perhaps Apollo), twelve cubits high, holding in his hand the figurehead of a ship”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 121: 1-2); and

•their statue at Delphi:

“... stood in the same place as the golden [statue of] Alexander the Macedonian”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 121: 2); and

✴ Philip II, in a letter that he sent to the Athenians in 340 BC (which is preserved in the corpus of Demosthenes’ work) claimed that:

“It was my ancestor, Alexander, who:

•first occupied the site [on which the Athenians had established the colony of Amphipolis in 437 BC]; and

•set up a golden andrias (statue) at Delphi as the aparchai [another term for first offerings] of the Persian captives taken there”, (‘Letter of Philip’, 12: 21).

Taken together, these records suggest that Alexander had taken and ‘occupied’ a Persian garrison at Ennea Odoi (the later site of Amphipolis) and used gold taken from the Persians that he captured (perhaps in the form of ransom) for a statue of himself that he presented at Delphi as akrothinia (first offerings), presumably for Apollo.

If Philip correctly located the place at which Alexander captured these unfortunate Persians, then this could suggest that he had abandoned his allegiance to the Persians immediately after their defeat at Plataea and emulated his Thracian neighbours in harassing the retreating army as it headed for the Hellespont: however, Nicholas Hammond and Guy Griffith (referenced below, at p. 102)

as Sławomir Sprawski (referenced below, at p. 139-40) pointed out, two sources from the 4th century BC certainly give this impression:

✴Demosthenes, in the oration ‘Against Aristocrates’, (which he wrote in ca. 352 for delivery by litigant called Euthycles), drew the attention of his audience to the case of:

“Perdiccas [sic], who was reigning in Macedonia at the time of the Persians’ invasion and destroyed them on their retreat from Plataea, bringing about the final defeat of the Persian king”, (‘Against Aristocrates’, 23: 200).

Demosthenes had clearly attributed to Perdiccas (Alexander’s son and successor) an honour that should have been attributed (whether accurately or not) to Alexander himself.

Furthermore, it would have been extremely rash of Alexander to overtly attacked his erstwhile Persian allies after Plataea, because:

as we shall see, the Persians still maintained a number of strong garrisons along the Aegaean coast, the most westerly of which was at Eion; and

he could not have been sure that Xerxes would not return.

at Delp

the two later testimonies are extremely unreliable:

✴Demosthenes recorded in his oration ‘On Organization’, which was broadly contemporary with ‘Against Aristocrates’ that:

“... when ‘Perdiccas’ [= Alexander], who was king of Macedonia at the time of the Persian invasions, destroyed the barbarians who were retreating after their defeat at Plataea, thereby completing the discomfiture of the Great King, [our forefathers] did not vote him the citizenship, but only gave him immunity from taxes”, (‘On Organisation’, 13: 24).

Furthermore:

•although Herodotus was aware that Alexander was a proxenos of Athens, he was apparently unaware that he had been awarded Athenian citizenship and/or exemption from Athenian taxes; and

•if Alexander actually had administered the coup de grâce to Xerxes’ invasion, Herodotus could hardly have been unaware of this fact.

✴Philip might well have invented the claim that the gold for Alexander’s statue at Delphi had been stripped from Persian soldiers whom he had captured when he had occupied the site of the Athenian colony of Amphipolis precisely because he wished to assert his own rights over that site.

However, in his account of Xerxes return march towards the end of the year (see below), Herodotus recorded that:

“It was then that a monstrous deed was done by the Thracian king of the Bisaltae and the Crestonian territory. He had refused to [become] Xerxes' slave, and fled to the mountains called Rhodope. He had also forbidden his sons to go with [Xerxes’] army to Hellas, but they had ... followed the Persians' march. For this reason, when all the six of them returned unscathed, their father tore out their eyes”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 116).

This suggests that, unlike Alexander and most of the leaders of the Thracian tribes, the [unnamed] king of the Bisaltae had refused to support Xerxes and had, instead, fled inland until the danger had passed.

Having traversed the northern Aegean coast, Xerxes

also traversed the coast of Thessaly, apparently unopposed. The Greek alliance led by Athens and Sparta held him up for a few days at Thermopylae : according to Herodotus:

“

but he subsequently then found a mountain pass that allowed him to march past them, at which point:

✴the allied fleet (which had similarly blocked the Persian advance at Artemesium) took refuge on the island of Salamis; while

✴Xerxes took the now-evacuated city of Athens and razed it to the ground.

However, the situation was transformed towards the end of the year, when the Greeks destroyed the Persian fleet at Salamis: Xerxes abandoned Attica and returned to Asia (as mentioned above), leaving his general Mardonius in Greece. According to Herodotus (at ‘Persian Wars’, 8: 126), Mardonius spent the winter in Thessaly and Macedonia. He also recorded that Mardonius sent Alexander to the Athenians in what proved to be an unsuccessful attempt to persuade them to change sides:

“He sent Alexander:

✴partly because ... Bubares, a Persian, had married Gygaea (Alexander's sister and Amyntas' daughter, who had given Bubares [a son], Amyntas of Asia, ... to whom the king gave Alabanda, a great city in Phrygia for his dwelling); and

✴partly because he learned that Alexander was proxenos (official trusted friend) and benefactor to the Athenians”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 136).

Note that, since Gygaea’s son was old enough in 480 BC to have been given ‘a great city in Phrygia for his dwelling’, it is clear that her marriage to Bubares must have taken place soon after the Persians first made contact with the Macedonians in 510 BC. Thus, although there is little other evidence for Alexander’s status with either the Persians or the Athenians before this time, we might reasonably assume that he had maintained good relations with both governments throughout his reign.

When Mardonius learned from Alexander that the Athenians had rejected his advances, he marched south into Attica and retook their still-deserted city. However, since the Spartans realised that the Athenians might surrender to Mardonius, who would then be able to make use of the Athenian navy, they re-assembled the Greek allies in Attica. Mardonius retreated towards Thebes, and the two armies finally faced each other at Plataea. Herodouts (at ‘Persian Wars’, 9: 31) recorded that the Macedonians fought in the Persian ranks, and that Mardonius positioned them facing the Athenians. He also recorded that Alexander secretly approached the Athenians at night and informed them the Mardonius would probably open the attack on the following day:

“I therefore urge you to prepare, and if (as may be) Mardonius should delay and not attack, wait patiently where you are; for he has but a few days' provisions left. If, however, this war ends as you wish, then you must take steps to save me too from slavery, since I have done so desperate a deed as this for the sake of Hellas ... I who speaks am Alexander the Macedonian”, (‘Persian Wars’, 9: 45).

On the following day, the Greeks won a decisive victory; Mardonius died in the battle and another general, Artabazos, led the Persian retreat: like Xerxes before him, he was keen to rech the Hellespont before the Athenian navt could block his passage. The immediate fate of Alexander (who might well have invented the story of his night visit to the Athenians in order to avoid the consequences of having chosen the losing side) is unrecorded: he presumably marched with Artabazos, who, according to Herodotus:

“... lead his army away straight towards Thrace through Thessaly and Macedonia without any delay, following the shortest inland road. So he came to Byzantium, but he left behind many of his army who had been cut down by the Thracians or overcome by hunger and weariness. From Byzantium, he crossed over in boats ... [and] returned to Asia”, (‘Persian Wars’, 9: 89).

It is possible that Alexander overtly changed sides at this point, and that he was among the ‘Thracians’ who harassed the retreating Persians. The evidence for this is related to a golden statue that Alexander dedicated at Delphi after Plataea:

✴Herodotus recorded that, after their victory at Salamis and their subsequent sack of Carystus :

•the Greek allies returned to Salamis, where they:

“... set apart from their spoils, akrothinia (first offerings) for the gods, [which included three Phoenician triremes that they sent to three different sanctuaries]. After that, they divided the spoils and sent off akrothinia to Delphi, from which was made an andrias (statue of a male figure, perhaps Apollo), twelve cubits high, holding in his hand the figurehead of a ship”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 121: 1-2); and

•their statue at Delphi:

“... stood in the same place as the golden [statue of] Alexander the Macedonian”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 121: 2); and

✴ Philip II, in a letter that he sent to the Athenians in 340 BC (which is preserved in the corpus of Demosthenes’ work) claimed that:

“It was my ancestor, Alexander, who:

•first occupied the site [on which the Athenians had established the colony of Amphipolis in 437 BC]; and

•set up a golden andrias (statue) at Delphi as the aparchai [another term for first offerings] of the Persian captives taken there”, (‘Letter of Philip’, 12: 21).

Taken together, these records suggest that Alexander had taken and ‘occupied’ a Persian garrison at Ennea Odoi (the later site of Amphipolis) and used gold taken from the Persians that he captured (perhaps in the form of ransom) for a statue of himself that he presented at Delphi as akrothinia (first offerings), presumably for Apollo.

If Philip correctly located the place at which Alexander captured these unfortunate Persians, then this could suggest that he had abandoned his allegiance to the Persians immediately after their defeat at Plataea and emulated his Thracian neighbours in harassing the retreating army as it headed for the Hellespont: however, Nicholas Hammond and Guy Griffith (referenced below, at p. 102)

as Sławomir Sprawski (referenced below, at p. 139-40) pointed out, two sources from the 4th century BC certainly give this impression:

✴Demosthenes, in the oration ‘Against Aristocrates’, (which he wrote in ca. 352 for delivery by litigant called Euthycles), drew the attention of his audience to the case of:

“Perdiccas [sic], who was reigning in Macedonia at the time of the Persians’ invasion and destroyed them on their retreat from Plataea, bringing about the final defeat of the Persian king”, (‘Against Aristocrates’, 23: 200).

Demosthenes had clearly attributed to Perdiccas (Alexander’s son and successor) an honour that should have been attributed (whether accurately or not) to Alexander himself.

Furthermore, it would have been extremely rash of Alexander to overtly attacked his erstwhile Persian allies after Plataea, because:

as we shall see, the Persians still maintained a number of strong garrisons along the Aegaean coast, the most westerly of which was at Eion; and

he could not have been sure that Xerxes would not return.

at Delpthe two later testimonies are extremely unreliable:

✴Demosthenes recorded in his oration ‘On Organization’, which was broadly contemporary with ‘Against Aristocrates’ that:

“... when ‘Perdiccas’ [= Alexander], who was king of Macedonia at the time of the Persian invasions, destroyed the barbarians who were retreating after their defeat at Plataea, thereby completing the discomfiture of the Great King, [our forefathers] did not vote him the citizenship, but only gave him immunity from taxes”, (‘On Organisation’, 13: 24).

Furthermore:

•although Herodotus was aware that Alexander was a proxenos of Athens, he was apparently unaware that he had been awarded Athenian citizenship and/or exemption from Athenian taxes; and

•if Alexander actually had administered the coup de grâce to Xerxes’ invasion, Herodotus could hardly have been unaware of this fact.

✴Philip might well have invented the claim that the gold for Alexander’s statue at Delphi had been stripped from Persian soldiers whom he had captured when he had occupied the site of the Athenian colony of Amphipolis precisely because he wished to assert his own rights over that site.

Read more:

Vivian A., “Rotting Ships and Bloodied Water: Destructive Liquids and Thucydides’ Skepticism of Naval Imperialism”, (2020), thesis of the University of California

Shepherd W., “Persian War in Herodotus and Other Ancient Voices”, (2019) Oxford

Yates D., “Tradition of the Hellenic League Against Xerxes”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 64:1 (2015) 1-25

Jim T., “Gifts to the Gods: Aparchai, Dekatai and Related Offerings in Archaic and Classical Greece”, (2011), thesis of St. Antony’s College, Oxford

Sprawski S., “Early Temenid Kings to Alexander I”, in:

Roisman J. and Worthington I. (editors), “A Companion to Ancient Macedonia”, (2010) Malden, MA and Oxford, at pp. 126-44

Flower M. A., “Simonides, Ephorus and Herodotus on the Battle of Thermopylae”, Classical Quarterly (New Series), 48:2 (1998) 365-79

Hammond N. G. L., “Sparta at Thermopylae”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 45:1 (1996) 1-2o

Hammond N. G. L. and Griffith G. T., “A History of Macedonia: Vol. II (550-336 BC)”, (1979) Oxford Evans J. A. S., “The ‘Final Problem’ at Thermopylae”, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 5:4 (1964) 231-7

Kraay C., “The Archaic Owls of Athens: Classification and Chronology”, Numismatic Chronicle (6th Series), 16 (1956) 43-68