Early Argead Rulers of Macedonia

Alexander I (ca. 500 - 450 BC):

Alexander and the Persians I: Darius the Great

Early Argead Rulers of Macedonia

Alexander I (ca. 500 - 450 BC):

Alexander and the Persians I: Darius the Great

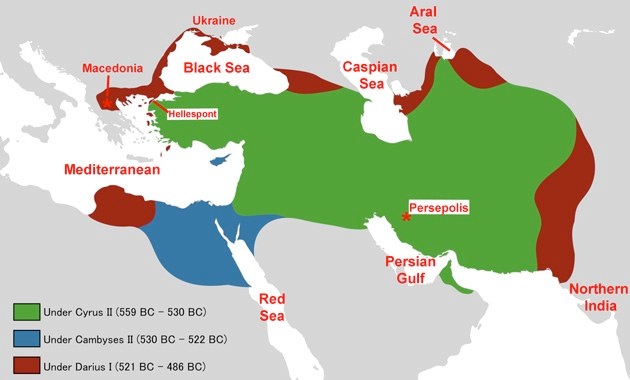

Achaemenid Empire (530 - 486 BC): Image from Wikipedia (my additions in red)

Introduction

Darius the Great (522 - 486 BC)

Carol King (referenced below, at p. 24) began her account of the reign of Alexander I with the observation that he made:

“... a grand entrance in the pages of history ... in Herodotus’ account of Persian advances into Europe.”

The Achaemenid King of Kings at this time was Darius I, otherwise known as Darius the Great. As Alireza Shapour Shahbazi (referenced below, search on ‘513’) observed:

“A major event in Darius’ reign was his European ... [campaign in] the region from [modern] Ukraine to the Aral Sea, [which] was the home of north Iranian tribes known collectively as Sakā [Greek: Scythians; Latin: Saccae]. ... [In] about 513 BC, Darius crossed the Bosporus into Europe, marching over a pontoon bridge built by his Samian engineer, Mandrocles.”

I discuss what is known about these events in my page on the Early Years of Darius’ Reign.

The important thing for our immediate purpose is that, according to Herodotus, when Darius returned from his Acythian campaign, he:

“... returned with his ships to Asia, leaving Megabazus as his general in Europe ...”, (‘Persian Wars’, 4: 143).

The account below begins with Megabazus’ ‘European’ campaign.

Herodotus

As Carol King (referenced below, at p. 24) observed:

“The stories that Herodotus tells about Alexander’s responses to the Persian encroachment quite possibly came from someone close to [Alexander], if not from [Alexander] himself, during a personal visit [that the historian made] to the Macedonian court in the middle years of the 5th century BC.”

Some scholars reject the suggestion that Herodotus had actually visited Macedonia, but Miroslav Vasilev (referenced below, 2016), who presented a detailed analysis of the relevant surviving sources, concluded (at p. 49) that:

“... Herodotus visited Macedonia at the very end of Alexander’s rule ... [and] personally communicated with [Alexander himself] and some Macedonian nobles.”

If this is correct (and I think that it is), then Herodotus’ account of the Persian Wars would have been almost finished by the time that of his visit to Macedonia. It is therefore likely that most of his scattered references to Alexander were added at this late stage (with some violence to the structure of the work).

In what follows, I largely rely on Herodotus’ account of the events. The most widely-used translation of his ‘Persian Wars’ is that of Alfred Godley, which was published by Loeb in 1922-5 (side by side with the Greek). I have included links to the on-line version of this translation in the website of Bill Thayer : the links to the translation by George Robinson and the commentary of Walter How and Joseph Wells (both referenced below) in the left margin in Bill’s web pages are particularly useful. I have sometimes modernised the language and, where precise wording is important, I have largely relied on the more recent translation of Robert Strassler (referenced below, 2006), which is also useful for its copious maps. Finally, Tom Holland’s ‘Persian Fire’ (referenced below) is a really good read and particularly useful in placing Herodotus’ work in a Persian (rather than a Greek) context.

Megabazus in Europe (513 - 510 BC)

Megabazus in Europe (ca. 510 BC BC)

(Detail from Robert Strassler, referenced below, 1996, Map 2:97, at p. 318, my additions in red)

Herodotus recorded that

“... subdued all the people of the Hellespont who did not take the side of the Persians”, (‘Persian Wars’, 4: 144: 3).

From this point, Darius had a bridgehead which would facilitate future invasions of Europe. In particular:

✴Sestus had been under Persian control at the time that Darius crossed the Hellespont; and

✴Herodotus also recorded that:

“The territory of Doriscus is in Thrace, a wide plain by the sea, and through it flows a great river, the Hebrus. Darius had established a Persian garrison [at Doriscus on the Hebrus] at the time of his march against Scythia”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 59: 1-2).

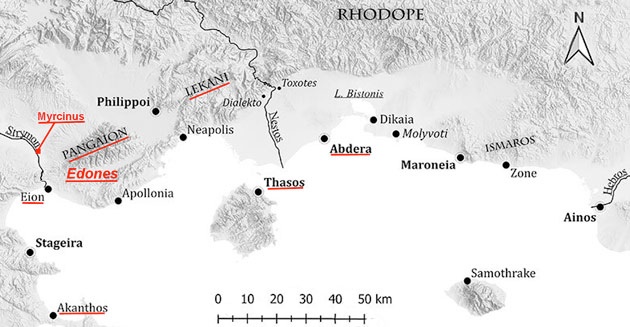

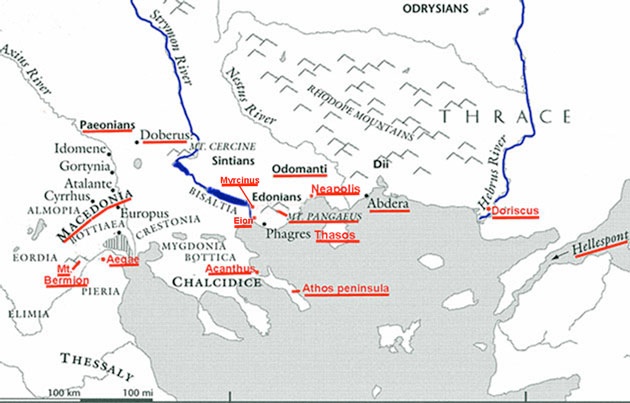

Thracian Coast

Image from Mustafa Adak and Peter Thonemann (referenced below, Map 2): my additions in red

Herodotus recorded that Megabazus:

“... marched his army through Thrace, subduing every city and every people of that region to [Darius’] will, because the complete conquest of Thrace was precisely what Darius had instructed him to accomplish”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 2: 2).

In a later passage, he recorded (probably more accurately) that:

“... Megabazus made the coast [of Thrace] subject to the Persians”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 10).

This suggests that Megabazus secured the submission of all the coastal settlements between the Strymon and the Hebrus, although (as we shall see) not necessarily by force.

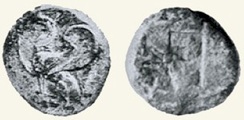

Abdera

‘Tetradrachm’ (weight unrecorded) of Abdera, from the Apadana Hoard (IGCH 1789) at Persepolis

Obverse: seated Griffin (the civic symbol of Abdera)

Reverse: Quadripartite linear square

Image from Erich Schmidt, referenced below, Plate 84, number 36, catalogued at p. 113:

also catalogued by John May (referenced below, at p. 60 as Period I, coin 4/1)

Edones, Myrcinus and Eion

According to Herodotus, when Darius had returned to Asia, he initially stayed at Sardis (the capital of the Persian satrapy of Lydia). His first action was to reward Histiaeus, the Greek tyrant of Miletus (the most important of the Ionian cities), who had been of great help to him against the Scythians. Asked what he wished for as his reward, Histiaeus:

“... asked for Myrcinus, in the territory of the Edones, so that he could establish a colony there”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 11: 1).

He later recorded that, when Megabazus returned to Darius. court at Sardis:

“... bringing with him the Paeonians [see below, ... he [reported to Darius that] Histiaeus was, by this time fortifying .... Myrcinus, by the river Strymon, ... [saying]:

‘Sire, ... you have allowed a clever and cunning Greek to build a city in Thrace, where there is abundant timber for building ships and oars and mines of silver, and many Hellenes and [Thracians] living nearby [whom he may one day lead in a rebellion against you. ... I advise you] to send for him ... and treat him gently, ... but make sure that he never returns to Hellas’”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 23: 1).

Darius duly ‘invited’ him to:

“... leave Miletus and your newly founded Thracian city [at Myrcinus], and follow me to Susa, where you shall have all that is mine as my table-companion and my counselor”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 24: 4).

Peter Delev (referenced below, 2007a, at p. 111, note 1) observed that since Darius

“... could not have had even pretended rights over the area before the expedition of Megabazus, this

might be taken as an indication that the ‘present’ [to Histiaeus] was given after the first successes of [Megabazus]; this reverses the order of events as told by Herodotus.

In other words:

✴Histiaeus probably received Myrcinus after Megabazus had taken it from the Edones: and

✴Megabazus subsequently became suspicious of his intentions, which he duly reported to Darius on his return to Sardis with the deported Paeonians (see below).

Miroslav Vasilev (referenced below, 2015, at p. 118) argued that Eion, where Boges was the Persian hyparch (governor) in 480 BC (see below) was probably also garrisoned at this time.

Peter Delev (referenced below, 2007b

Paeonia

According to Herodotus, soon after Darius return to Sardis:

“... two Paeonians [arrived there] ... because they wanted to rule as tyrants over the Paeonians [as his vassal]. They had brought with them their [exceptionally striking] sister, ”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 12: 1).

Herodotus then launched into an improbable anecdote in which Darius:

✴was much impressed by the sister (as the would-be tyrants had intended); but

✴disappointed them by ordering:

“... Megabazus, whom he had left as his general in Thrace, remove the Paeonian men, women, and children from their homes and bring them to [Sardis]”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 14: 1).

The Paeonians apparently marched out to oppose Megabazus, whom they assumed would advance from the coast, but he came from a different direction and easily took their undefended inland territory. When they realised what had happened:

“... the Paeonians immediately broke ranks and surrendered to the Persians. That is how the Paeonians, the Siriopaeones [see below], the Paeoplae [see below] and all the inhabitants of the land as far as the Lake Prasias were uprooted from their homes and deported to Asia”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 15: 3).

However, not all of the Paeonians were deported to Asia:

“... those around Mount Pangaion and near the Doberes, the Agrianes and the Odomanti, as well as those around Lake Prasias itself, were never subdued by Megabazus, albeit he tried to take the lake-dwellers ... (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 16: 1)

As Peter Delev (referenced below, 2015, at p. 112) observed, the term ‘Paeonians’;

“... clearly designates an ethnically differentiated tribal group, and some of the constituent ... tribes are explicitly specified by Herodotus, whether by name or otherwise. Among these, the case of the Siriopaeones is most clear; they are mentioned here among the Paeonian tribes who were transferred to Asia by Megabazus and again explicitly as Paeonians in 480 BC in a casual notice of their city, Siris [see my page Alexander I: Persians II - link needed].”

Macedonia

According to Herodotus,

“Megabazus, having made the Paeonians captive, sent as messengers into Macedonia [see below]. ... Now there is a very straight way from Lake Prasias to Macedonia:

✴leaving the lake, [one passes] the mine from which Alexander was later later extract a talent of silver a day; and

✴from there, one only needs to cross Mount Dysorum to reach Macedonia”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 17: 1-2).

In the middle of this passage, we learn the nature of this journey: Megabazus sent:

“... the seven Persians who (after himself) were the most honourable in his army to [King Amyntas of Macedonia, Alexander’s father] to demand earth and water for [i.e. submission to] Darius the king”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 17: 1).

Herodotus then repeated what is almost certainly the Macedonians’ own apocryphal account of a very ‘Greek’ symposium that Amyntas gave for the (uncouth Persian) envoys, before retiring to his bed, at which point, the precocious Alexander (already acting as heir apparent) invited Persians to:

“... tell your king who sent you how hospitably his Ἕλλην Μακεδόνων ὕπαρχος (Greek hyparchos/governor of the Macedonians) received you ....”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 20: 4).

With that, Alexander had the envoys and murdered. Unsurprisingly:

“Soon afterwards, the Persians made a great search for these men; but Alexander [bribed the search party] with the gift of a great sum [of money. ... He also gave the hand of] his own sister Gygaea to Bubares, a Persian, the general [in charge of the search party]; by this gift he made an end of the search [for the murdered men]”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 21: 2). (

We later learn that Bubares was the son of Megabazus.

We need not doubt that Amyntas did send earth and water to Darius at this point since we subsequently learn that Gygaea did indeed marry Bubares at about this time: in his account of the events of 479 BC, Herodotus recorded that the Persian general Mardonius chose Alexander as his envoy to the Athenians (see below):

“... partly because ... Bubares, a Persian, had married Gygaea Alexander's sister and Amyntas' daughter: she had [given him a son], Amyntas of Asia, .. [to whom Xerxes, Darius’ son and successor, gave Alabanda, a great city in Phrygia, for his dwelling”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 136).

Since Gygaea’s son was old enough by 479 BC to have been given ‘Alabanda ‘for his dwelling’, her marriage to Bubares can hardly have taken place much later than 510 BC. Nor should we be surprised at Amyntas’ decisions at this time: he had surely calculated that:

✴his position at the western edge of Darius’ empire; and

✴the fact that his son-in-law was one of Darius’ senior officers;

would mean that he would be left in peace to run his ‘kingdom’ as he wished, even if it was nominally a Persian satrapy. (We might also wonder how much he gained from the deportation to Phrygia of at least some of his Paeonian neighbours to the north.)

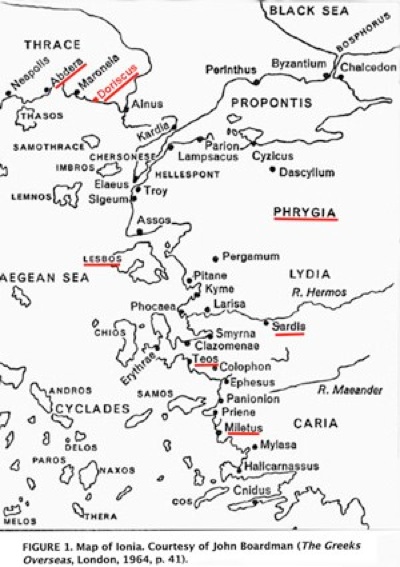

Ionian Revolt (499 - 493 BC)

Image from Ernst Badian, referenced below, Figure 1 (my additions in red)

In 499 BC, Aristagorus, who was Histiaeus’ successor as the Persian-appointed tyrant of Miletus, secured the Athenians’ support for the revolt that he was about to unleash against Darius’ rule in Ionia. Having secured the assistance of 20 Athenian ships, he sent a messenger:

“... ... to the Paeonians who had been had been deported from the Strymon by Megabazus and now lived in a village of their own in Phrygia”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 98: 1-2).

It seems that this messenger warned them about the forthcoming revolt and promised them that, should they they find their way to the coast, the rebels would help them to return to their homeland. It seems that a number of them who accepted this offersucceded in reaching the island of Lesbos, and:

“... the Lesbians ferried them to Doriscus, from where they made their way by land to Paeonia”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 98: 4).

Soon after, with the aid of the Athenians, the rebels:

“... came to Sardis and took ... all of it except the citadel, which was held by Artaphrenes, [Darius’ brother] ...”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 100).

Although the motive for this attack had been to encourage the Lydians to join the revolt, all hope of that ended with the fire that devoured the city:

“So Sardis was burnt, and therein the temple of Cybebe, the goddess of that country; which burning the Persians afterwards made their pretext for burning the temples of [Athens in 480 BC]”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 100).

At this point, having achieved nothing except the hatred of Darius, the Athenians withdrew. The Ionian Greeks proved to be no match for Darius, and were finally defeated in a naval battle off the island of Lade, which faces Miletus.

Mardonius in Europe (492 BC)

Mardonius in Europe (492 BC)

(Detail from Robert Strassler, referenced below, 1996, Map 2:97, at p. 318, my additions in red)

According to Herodotus, in 492 BC:

“... at the beginning of spring, Mardonius son of Gobryas, a young man who:

✴had recently married Artozostre, the daughter of Darius; and

✴was the only [Persian] general left in office, since Darius had discharged the others;

led a large army and a large fleet down to the coast. ... [While his army marched to the Hellespont], he sailed with the fleet along the Ionian coast, where] ... he deposed all the Ionian tyrants and set up democracies in their cities, [presumably in order to reduce the likelihood of another Ionian revolt]. ... This done, he sailed with his fleet to the Hellespont, where his army was already assembled, and [the combined forces crossed the Hellespont, ... with Eretria and Athens for their goal”, (‘Persian Wars’, 6: 43).

Herodotus then gave a very brief account of Mardonius’ campaign, in which he noted that, while the Athenians were its avowed target, the real mission was:

“... to subdue as many of the Greek cities as they could. First, their fleet subdued the Thasians, who did not so much as lift up their hands against it. ... [The fleet teh sailed] along the coast as far as Acanthus .... [It then attempted to continue around the Athos peninsula, but ... [sailed into one of the huge storms for which the peninsula was famous]. It is said that about 300 ships more than 20,000 men were lost”, (‘Persian Wars’, 6: 44).

Meanwhile, according to Herodotus, after the subjugation of Thasos, Mardonius and his land army:

“... added the Macedonians to the slaves that they had already (for all the nations nearer to them than Macedonia had been made subject to the Persians before this)”, (‘Persian Wars’, 6: 44).

As we have seen, Alexander (who had probably succeeded Amyntas in 496 BC) was already the brother-in-law of the Persian noble Bubares by this time and, furthermore, Bubares had named his son (Alexander’s nephew) as Amyntas (which indicates that this marriage had been of considerable political importance). It seems to me that Herodotus had probably written this passage before his visit to Alexander’s court, at a time when he had yet to discover these important details. In fact, the likelihood is that Alexander (like Amyntas before him) enjoyed significant political advantages as hyparchos (governor) of the Macedonians.

Herodotus concluded by recording that:

“While Mardonius’ army was camped in Macedonia, the Βρύγοι (Brygoi 0r Bryges) of Thrace attacked them by night and killed many of them, wounding Mardonius himself. ... After subduing the Bryges, he led his forces back [to Asia], since:

✴the Byrges had dealt a heavy blow to his army; and

✴Athos had dealt an even heavier blow to his fleet.

This expedition after an inglorious adventure returned back to Asia”, (‘Persian Wars’, 6: 45).

If the Athenians had indeed been Mardonius’ ultimate target, then the destruction of his navy would have put this target out of reach.

Reconstruction of Mardonius’ Campaign

Miroslav Vasilev (referenced below, 2015, at p. 146) argued that, having croseed having crossed the Hellespont, the likelihood is that Mardonius’ assembled his land and naval forces at Doriscus. We know from Herodotus that the fleet subjugated Thasos, and he also recorded that, in 491 BC:

“... sent a message ordering the Thasians, whose neighbours had falsely reported that they were planning rebellion, to destroy their walls and bring their ships to Abdera”, (‘Persian Wars’, 6: 46).

Vasilev (as above) argued (at

The citizens of this polis [almost certainly] submitted and probably acquired the status of one of the main Persian bases in the region, [since], two years later, the entire Thasian navy was taken to Abdera by order of [Darius - see].”

This fits in with Mardonius’ subsequent subjugation of Thasos eraly in his campaign. Furthermore, Vasilev (as above) argued that, since the fleet apparently continued as far as Acanthus without any problems, the likelihood is that, by this time:

“... all the Greek cities, situated between Abdera and Acanthus, as well as the citizens of Acanthus ... [recognised Darius’] authority.”

Vasilev (as above) assumed that Mardonius and his army was shadowed by the fleet as far as Abdera and picked them up again at Neapolis (a Thasan colony on the opposite coast) and argued (at p. 147) that he probably subjugated the Agrianes, the Odomanti and the Doberes who had escaped Megabzus’ attention in 510 BC (see above) before briefly rejoining the fleet. Then, as the fleet set of for Acanthus, he argued (at p. 154) that:

“... the infantry took the shortest route to the Thermaic Gulf and ... was at night by the Bryges ... “

He argued (at p. 150) that, although the territory of the Bryges is variously located in our surviving sources, the testimony of a surviving fragment Strabo should probably be accepted:

“..., in earlier times, Mount Bermium was occupied by the Thracian tribe of the Bryges; some of these crossed over into Asia and their name was changed to Phryges”, (‘Geography’, 7: fr. 25).

Vasilev (as above) concluded by noting that:

“Having conquered the Bryges, Mardonius continued towards the Thermaic Gulf. His arrival at the east border of Macedonia forced its ruler Alexander to voluntarily accept [Darius’] authority.”

As noted above, I believe that Alexander had accepted Darius’ authority since ca. 510 BC.

the Argead Dynasty [link needed].

Read more:

Adak M. and Thonemann P., “Teos and Abdera: Two Cities in Peace and War”, (2020) Oxford

King C., “Ancient Macedonia”, (2018) London and New York

Vasilev, M. I., “The Date of Herodotus’ Visit to Macedonia”, Ancient West and East, 15 (2016) 31-51

Vasilev, M. I., “The Policy of Darius and Xerxes towards Thrace and Macedonia”, (2015) Leidon and Boston

Strassler R., “The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories”, (2009) New York

Delev P. (2007a), “Tribes, Poleis and Imperial Aggression in the Lower Strymon Area in the 5th Century BC: The Evidence of Herodotus”, in:

Iakovidou A. (editor), “Thrace in the Graeco-Roman World: Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of Thracology, Komotini - Alexandroupolis, 18-23 October 2005”, (2007) Athens, at pp. 110-119

Delev P, (2007b) “The Edonians”, Thracia, 17 (2007) 85-106

Holland T., “Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West”, (2005) London

Badian E.,. “Ionian Revolt”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, 13:2 (2004) 188-95

Strassler R., “The Landmark Thucydides: a Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War”, (1996) New York

Shahbazi A. S., "Darius the Great", Encyclopaedia Iranica, 7:1 (1994) 41–50

May J.M.F., “The Coinage of Abdera”, (1966) London

Schmidt E. F., “Persepolis II: Contents of the Treasury and Other Discoveries”, (1957) Chicago

How W. W. and Wells J., “Commentary on Herodotus”, (1912) Oxford

Rawlinson G., “History of Herodotus”, (1910) London and New York