Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Rhesus

Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Rhesus

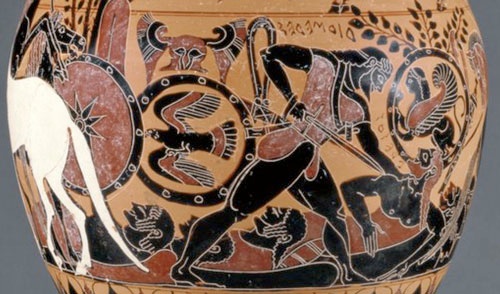

Detail of one side of a black figure, Chalcidinian neck amphora (ca, 550 BC) by the so-called Inscription Painter,

depicting a scene from Homer’s ‘Iliad’ in which the Argive Diomedes murders the Thracian King Rhesus, a Trojan ally

Diomedes and Rhesus are identified by inscription and Rhesus’ ‘snowy white horse’ is to the left

From the Greek colony of Rhegion in Southern Italy, now in the Getty Museum, Malibu, California

Image from a post by Michel Lara

Rhesus in the ‘Iliad’

Homer’s short account of Rhesus at Troy described the events of a single night, on which Rhesus arrived at the camp of Hector, prince of Troy, belatedly honouring his obligation to support his ally against the Greek invaders. At about the time of Rhesus’ arrival, a Trojan called Dolon was captured by two Greek spies, Odysseus and Diomedes. He tried to placate them by treacherously advising them that:

“... if you are eager to enter the Trojan camp, here at its edge are the newly arrived Thracians and their king, Rhesus, son of Eïoneus. His horses are truly the fairest that ever I saw, whiter than snow and as fast as the wind. His chariot is made of gold and silver, and his heavy golden armour is a wonder to behold. Indeed, it is not right that mortal men should wear such armour, [which should be reserved for] the immortal gods”, (‘Iliad’, 10: 433-440, based on the translation of Augustus Murray, referenced below, at p. 481).

Homer’ designation of Rhesus father as ‘Eïoneus’ might imply that:

✴he was the founder of Eion, a city on the east bank of the Strymon; or

✴his name was also the ancient name of the river Strymon (see below).

Dolon’s treachery was in vain, since Diomedes murdered him anyway, after which, he and Odysseus crept up on the camp of the exhausted Thracians, where Rhesus slept, surrounded by his men, with their horse beside them, tethered to the chariots. Diomedes began putting sleeping Thracians to the sword while Odysseus pulled their bodies aside in order to steal the horses, and the slaughter only stopped when Diomedes:

“... came to [Rhesus himself and] robbed him, his thirteenth victim, of honey-sweet life, while he was breathing heavily. For, an evil dream stood over [Rhesus’] head that night [in the form of Diomedes], by the contrivance of Athena”, (‘Iliad’, 10: 494-497, see the translation and commentary by Nadia Sels, referenced below).

Despite Rhesus’ relatively unimportant appearance in the ‘Iliad’, the scene of his murder was depicted on Greek vases from an early date. For example, on the ‘obverse’ of the vase (ca. 550 BC) illustrated above, the Inscription Painter depicted Rhesus looking up as Diomedes prepares to kill him: he is presumably trying to work out if he is dreaming, reflecting Homer’s line in which:

“... an evil dream stood over [Rhesus’] head that night [in the form of Diomedes], by the contrivance of Athena.”

Rhesus’ horse, ‘whiter than snow‘, stands to to the left and, on the ‘reverse’ of the vase,the Inscription Painter departs from Homer’s account by depicting Odysseus killing one of Rhesus’ men.

The ‘Rhesus’ Attributed to Euripides

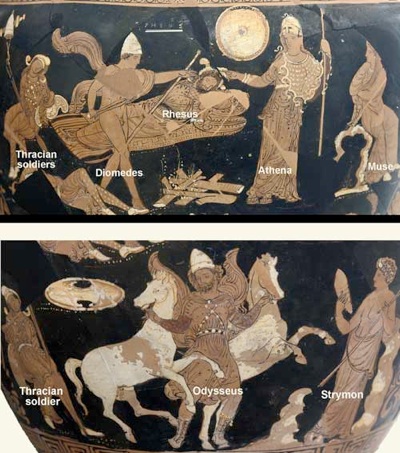

Apulian red-figure krater (ca. 340 BC) by the so-called Darius Painter (Side A)

My additions in white (including the underlining of the inscription identifying Rhesus in the upper image)

Now in the Antikenmuseum, Berlin (image from Wikimedia)

As Almut Fries (referenced below, at p. 66) observed, the likelihood is that the ‘Rhesus’ was written be a pseudo-Euripides in ca. 380 BC. This tragedy also dealt with the events of the fateful night on which Rhesus arrived at the camp of Hector. A messenger informs Hector of the (albeit belated) arrival of an ally, the ‘gold-armoured Rhesus’ and the chorus describe him as:

“... son of the river god, ... [who is] most welcome, since it has taken long for your Pierian mother and the river of lovely bridges to send you here. The Strymon it was who once eddied in watery wise through the virginal body of the Muse, the singer, and begot your fine manhood”, (‘Rhesus’, 346-354, translated by David Kovacs, referenced below, at p. 391)

Thus:

✴while Homer described Rhesus as ‘son of Eïoneus’

✴the chorus in the ‘Rhesuss’ described him as the son of the river god Strymon and a Pierian muse.

In his ‘Bibliotheca’, the patriarch Photius summarised the ‘Narratives’ of Conon, a mythographer who wrote in the Augustan period, and one of these summaries relates to this discrepancy:

“... the fourth narrative talks about ... Strymon, who ruled the Thracians and gave his name to the river formerly known as Eioneus. He had three sons, Brangas and Rhesus and Olynthus. Rhesus went to fight alongside Priam at Troy and was killed by Diomedes”, ‘Bibliotheca’, 4).

Peter Delev (referenced below, at p. 3 and note 17) for other indications that Eioneus was an ancient name of the river Strymon.

Rhesus explains that he has been delayed by the Scythians’ attack on his lands, but promised that:

“Although I have come late, my coming is timely. This is already the 10th year you have been waging war without effect, and day after day you cast your dice in war against the Argives. But, for me, a single day will suffice to pillage the Achaeans’ towers, fall upon their ships, and kill them. I shall leave Ilium for home on the following day, having shortened your labours. None of you need take shield in hand: I shall come back having plundered the boastful Achaeans with my spear, latecomer though I am”, (‘Rhesus’, 346-354, translated by David Kovacs, referenced below, at p. 399).

Athena appears to Odysseus and Diomedes to warn them that Rhesus has arrived and that:

“If he survives until morning, neither Achilles nor the spear of Ajax will prevent him from destroying all the Argives’ beached ships, breaking down the palisades and cutting a wide swath with his spear within the gates. However, if you kill him, all is yours”, (‘Rhesus’, 600-604, translated by David Kovacs, referenced below, at p. 415).

They act accordingly, and Hector soon learns of Rhesus‘ death, after which, the unnamed muse (Rhesus’ mother) appears with the body. She exclaims before Hector that:

“... this is your doing, Athena, cause of this whole disaster, for neither Odysseus nor [Diomedes is responsible for the deed]”, (‘Rhesus’, 938-940, translated by David Kovacs, referenced below, at p. 449).

We learn nothing in the ‘Iliad’ about the fate of Rhesus’ body. However, the next passage in the ‘Rhesus’ fills this gap: when the unnamed Muse who had given birth to him (having been impregnated by the river-god Strymon) appears to Hector carrying his body, she assures Hector that he does not need a funeral because he:

“... will not enter the ground of black earth. This much I shall ask of [Persephone], the daughter of the corn-bearing goddess Demeter: to release his soul onto the Upperworld. She is, after all, indebted to me, and must openly honour Orpheus' kin.

✴So, as far as I am concerned, from now on, he will be as good as dead and as one who does not behold the light; for we shall never meet again, nor will he ever see his mother's figure.

✴However, he shall still lie hidden in the caverns of the silver-veined land, seeing the light, a man-god, a prophet of Bacchus who dwells on rocky Pangaeum as a revered god amongst those who have knowledge”, (‘Rhesus’, 962-973, translated by Vaios Liapis, referenced below, 2007, at p. 395).

Rhesus and the Thraco-Macedonian Coinage

‘Signed standing horseman octadrachm’ of the Bisaltae (28.68 gm)

Obverse: CIΣALTIKΩN (of the Bisaltae): naked horseman wearing a petasus (wide-brimmed hat),

carryings two spears and walk asserted thating behind his horse

Reverse: quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image from CNG (Triton 18, 2015; lot 427)

Lisa Kallet and John Kroll (referenced below, at p. 79, Figure 4.5) illustrated this coin and asserted that:

“The nude horseman ... wearing a [petasus], carrying two spears and walking next to his horse is a Thracian divinity or hero.”

This ‘standing horseman’ was not unique to the ‘signed octadrachms’ of the Bisaltae:

✴Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below) catalogued:

•80 ‘octadrachms’ of of this type ‘signed’ by the Bisaltae (coins 1- 79 at pp. 82-103 and coin 113, at p. 113); and

•41 ‘octadrachms’ without inscription, attributed to either the Bisaltae or Alexander I of Macedonia (coins 81-132, at pp, 104-113);

✴Doris Raymond catalogued 13 ‘signed octadrachms’ by Alexander (coins 45-57, at pp, 100-1)

✴a ‘signed octadrachm’ of Mosses (perhaps a king of the Bisaltae) appeared on the market in 2009.

Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at Table 22, p. 385) suggested the likely chronological order of these ‘octadrachms’ (which he designated as tristaters), along with associated tetrobols, where these are known. (In his final group, his type ‘cavalier’, which is ‘signed’ by Alexander, the putative hero is mounted on his horse, rather than walking behind it).

Joannes Svoronos

As long ago as 1919, Joannes Svoronos (referenced below, at pp. 105-6) suggested that the ‘standing horseman’ on the Thraco-Macedonian coins:

“... very probably represents the famous Heros equitans of the country, the son of the Strymon, Rhesus, who, after his death before Troy, was transported to the silver-rich country of his kingdom, where he continued to exist as a demon [or man-god]”, (my translation).

He quoted a passage from the ‘Rhesus’ (see above) in which the unnamed Muse who had given birth to him (having been impregnated by the river-god Strymon) appears to The Trojan prince Hector (with whom Rhesus was allied at the time of his murder, carrying the body of her son and assures Hector and his court that:

“... he shall lie hidden in the caverns of the silver-veined land, seeing the light, a man-god, a prophet of Bacchus who dwells on rocky Pangaeum, as a revered god amongst those who have knowledge”, (‘Rhesus’, 962-973, translated by Vaios Liapis, referenced below, 2007, at p. 395).

He then observed that the revered man-god Rhesus:

“... living in the caves of the country's silver mines, was the most suitable type to adorn the coins made from the product of these mines”, (my translation).

Sixty years later, Nicholas Hammond and Guy Griffith (referenced below, at p. 77) asserted that it is ‘generally agreed’ that the:

“... naked warrior with two spears [standing] beside a horse [on the Bisaltian ‘octodrachms’] represents Rhesus, who was worshipped by the Bisaltae in a cave of this ‘silver-veined land’ ...”;

citing for this proposition:

✴the passage for the ‘Rhesus’ quoted above;

✴the geographer Strabo, who was writing in the Augustan period; and

✴the military strategist Polyaenus, who was writing in the 2nd century AD.

Of these, the testimony of Strabo is the most straightforward: he recorded that:

“... the land on the far side of the Strymon ... is [that] of the Odomantes, the Edonians and the Bisaltae (both those who are indigenous and those who crossed over from Macedonia), amongst whom Rhesus was king”, (‘Geography’ , 7: 36).

As Vaios Liapis (referenced below, 2007, at p. 396) observed:

“Strabo seems to place Rhesus' kingdom somewhere east of the river Strymon, among the Thracian tribes of the Odomantes, the Edonians and the Bisaltae. Indeed, Bisaltian coins depict a naked warrior, holding two spears and standing beside a horse, [who is] perhaps a figure of cult ... [and] has been identified with Rhesus by at least one specialist [Nicholas Hammond - see his note 75], although this of course must remain purely conjectural.”

It seems to me that Strabo’s testimony might also allow the conjecture that the standing man wearing a petasus on the ‘octadrachms’ of Edones might also be identified as King Rhesus,

The testimony of Polyaenus does not take matters on from here: he recorded that, in 437 BC, the Athenian general:

“... Hagnon led an Athenian colony, intending to occupy the so-called Ἐννέα ὁδοὺς (Ennea Odoi, literally ‘Nine Ways’) on the Strymon. The Athenians received the following oracle:

‘Do you desire to found anew the place trodden by many feet, O youth of Athens? It will be difficult for you without the gods, ... and they will not allow it until you seek and bring from Troy the remains of Rhesus and piously conceal them in his native soil. Then might you obtain renown.”

When this was revealed by the god, the general Hagnon sent men to Troy who dug up the grave of Rhesus by night and took away the bones. Having wrapped them in a purple chlamys, they brought them to the Strymon. The barbarians who occupied the place forbade them to cross the river, but Hagnon agreed a three-day truce with them and sent them away, Then, during the night, he crossed the Strymon with his army and buried the bones of Rhesus near its banks. He constructed trenches around the spot and fortified it by the light of the moon, but did not work during the day. And the whole work was accomplished in three nights. When the barbarians came back three days later, they saw the wall built and accused Hagnon of having broken the truce. He, however, denied any wrong doing, saying that they had made a truce for three days and not for three nights. In this way, Hagnon occupied the [site of Ennea Odoi] and called the city Amphipolis”, (‘Stratagems’, 6: 53, based on the translation by Michael Vickers, referenced below, at p. 77).

There is no reason to doubt that Hagnon did indeed establish a hero-cult for Rhesus at Amphipolis in 437 BC: as Marco Fantuzzi (referenced below, at pp. 10-11) observed:

“Transferring the [presumed] bones of a hero was a relatively common practice in hero-cults ...”

Vaios Liapis (referenced below, 2011, at p. 104) similarly remarked that:

“... the cult of Rhesus as practiced in the Athenian colony of Amphipolis [from 437 BC] ... conformed to well-known patterns of Greek hero-cult: the tomb [on the Strymon], where Rhesus’ talismanic remains were thought to lie, was the centre of cultic activity.”

However, he observed that the Thracian cult of Rhesus, as evidenced in the ‘Rhesus’ and in Philostratus’ ‘Heroicus’:

“...seems to have shared none of the essential qualities of this standard type of Greek hero-cult ...”

Thus, if we are looking for evidence that the man in the petasus who adorned the obverses of the Thraco-Macedonian ‘octadrachms’ of the first half of the 5th century BC was (or, was sometimes) identified as Rhesus, then we must look for it in the ‘Rhesus’ and/or the ‘Heroicus’.

Rhesus in the ‘Heroicus’

In Philostratus’ ‘Heroicus’ a devout farmer argues in favour of the power and efficacy of the cults of the Homeric heroes. Jeffrey Rusten and Jason König (referenced below, at p. 6) argued that its author was almost certainly the man of this name who began his career under the Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211 AD). They translated the passage in question as follows:

“You should also know about Rhesus the Thracian: for he, whom Diomedes killed at Troy is said to inhabit Rhodope [see the map above], where they celebrate many of his wonders in song. They say that he keeps horses does armoured training, and engages in hunting. They also say:

✴that the hero’s hunting is confirmed by the fact that wild boar, roe deer and all animals living in the mountains visit his βωμὸν (bōmos, sacrificial altar) in groups of two or three and, without any [force being applied to] them, offer themselves to the knife and are sacrificed’ and

✴that he keeps his borders safe from plague.

Rhodope is in fact very populous, and many [presumably thriving] villages surround the sanctuary”, (‘Heroicus’, 17: 3-6, translations by Jeffrey Rusten and Jason König, referenced below, at pp. 155-7 and by Marco Fantuzzi, referenced below, at p.13).

As Vaios Liapis (referenced below, 2011, at p. 97) observed:

“... with Philostratus, it is never easy to disentangle factual information from fictional elaboration ... [However], even his detractors do not doubt the essential premise of [this passage] ... , namely that a cult of Rhesus did obtain in Thrace.”

Thus, at least in the late 2nd century AD, Rhesus had an active cult at Rhopode. As Marco Fantuzzi observed:

“It is [conceivable] that the Rhodopian Rhesus was a new hero of the Imperial age ... However, in view of his designation as a [Homeric] hero by Philostratus, it is more probable that he had been receiving heroic honours in the Rhodope region for a long time.”

Vaios Liapis (referenced below, 2011, at p. 97) observed that:

“Philostratus’ account of Rhesus’ cult at Rhodope has a lot in common with what we know about the cult of the indigenous Heros Equitans, [the ubiquitous ‘Thracian Horseman’]; and, even if Philostratus is merely confusing the Heros with Rhesus, this could be at least partly due to genuine cultic affinities between the two figures.”

In other words, it is possible that the cult at Rhodope was manifestation of a cult of Rhesus, the Heros Equitans, that had been ubiquitous across Thrace for centuries.

As Marco Fantuzzi (referenced below, at p. 7) pointed out, surviving fragments of a poem (6th century BC, also translated by Douglas Gerber, referenced below, at p. 407) records that:

“... [while sleeping near?] the towers of Ilium by his chariot and white Thracian horses, Rhesus, king of the people of Ainos, was despoiled of them ...”

Interestingly, this might well refer to the city of Ainos at the mouth of the Hebros river.

Herodotus then recorded that, when Xerxes reached the Strymon:

“... the Magi sacrificed white horses in order to obtain favourable omens [presumably before crossing the river]”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 113: 2).

Furthermore, having crossed the river:

“... at the Edonian town of Ennea Odoi [literally Nine Ways] by the bridges which they found thrown across it, [presumably the bridge built by Bubares and Artachaees] and learning [its name], they buried alive that [nine] boys and girls from the local area. Burying alive is a Persian custom; I have heard that, when Xerxes' wife Amestris reached old age, she had fourteen sons of Persian nobles buried alive, presenting them in place of herself to the god who is said to be under the earth”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 114).

Iconography of the Standing and Mounted Horsemen

Details from the outside of the Attic red-figure kylix (ca. 489 BC) that for which the ‘Dokimasia Painter’ is named

From Orvieto, now in the Antikenmuseum, Berlin (image from Jenifer Neils, referenced below, p. 86, Table 1.2)

The broadly contemporary designs on an Attic kylix illustrated above feature an equestrian procession in which young men wearing chlamys and petasus and carrying two spears marshall the horses. Anna Maria Prestianni-Giallombardo and Bruno Tripodi (referenced below, at pp. 322-2 and p. 352, Figures 1 and 4) noted the ‘iconographic analogies’ between the ‘standing horseman’ obverses of Alexander’s ‘octodrachms’ and the motif above on the left, particularly in relation to:

“... the peculiar iconic motif of the horseman’s lowered head”, (my translation).

This suggests that the obverse designs under discussion here designs might have had Athenian (non-numismatic) sources. As Jenifer Neils (referenced below, at p. 85) observed, the unknown artist was given this name because it was thought that the scenes depicted an official inspection, known as the dokimasia, in this case for the cavalry (although, as she pointed out at note 5, another suggestion is that suggested that it depicted the preliminaries to a festival or procession). It certainly seems that the young men expertly marshalling the horses were horsemen (rather than officials), and they might well have been serving in (or applying to serve in) the Athenian cavalry.

Base of an Attic, red figure kylix (500-490 BC) attributed to Onesimos

From Vulci (now in the Louvre Museum, Paris)

However, this obverse type seems to have been very uncommon outside Alexander’s coinage. Interestingly, the slightly earlier design illustrated above, which also features a mounted horseman wearing a chlamys and petasus and carrying two spears suggests that might have been taken from an Athenian (non-numismatic) source.

This ancestor could have been Hesiod’s Macedon, the son of Zeus and the nephew of Hellen (the ancestor of all the Hellenes (Greeks). However, as I discuss below, I think that a number of factors point instead to Perdiccas, son of Temenus.

Read more:

Fantuzzi M., “The Rhesus Attributed to Euripides”, (2020) Cambridge and New York

Kallet L. and Kroll J. H., “The Athenian Empire: Using Coins as Sources”, (2020) Cambridge

Carney E. D., “Eurydice and the Birth of Macedonian Power”, (2019) Oxford and New York

Coblentz D. K., “Macedonian Succession: A Game of Diadems”, (2019) thesis of the University of Washington

Fries A., “The Rhesus”, in:

Liapis V. and Patrides A. K. (editors), “Greek Tragedy After the Fifth Century: A Survey from ca. 400 BC to ca. AD 400”, (2019) Cambridge and New York, at pp. 65-88

Kõiv M., “Manipulating Genealogies: Pheidon of Argos and the Stemmas of the Argive, Macedonian, Spartan and Median Kings”, Studia Antiqua et Archaeologica, 25:2 (2019) 261-76

Fleischer K., “Die Älteste Liste der Könige Spartas : Pherekydes von Athen (PHerc. 1788, col. 1)” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 209 (2019) 1-24

King C., “Ancient Macedonia”, (2018) London and New York

Vasilev, M. I., “The Date of Herodotus’ Visit to Macedonia”, Ancient West and East, 15 (2016) 31-51

Rusten J. and König J. (translators), “Philostratus: Heroicus; Gymnasticus; Discourses 1 and 2”, (2014) Cambridge MA

Sels N., “Ambiguity and Mythic Imagery in Homer: Rhesus' Lethal Nightmare”, The Classical World, 106:4 (2013) 555-70

Neils J., “The Dokimasia Painter at Morgantina”, in:

Schmidt S.and Stähli A.(editors) , “Vasenbilder im Kulturtransfer-Zirkulation und Rezeption Griechischer Keramik im Mittelmeerraum”, (2012) Munich, at pp. 85-92

Tzamalis A. R., “Les Ethné de la Région ‘Thraco-Macédonienne’: Etude d’Histoire et de Numismatique (fin du VIe - Ve siècle)”, (2012) thesis of the University of Paris (Sorbonne)

Griffith-Williams, B. "The Succession to the Spartan Kingship, 520-400 BC", Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, 54:2 (2011) 43–58

Guth D. S., “Character and Rhetorical Strategy: Philip II of Macedonia in Fourth Century Athens”, (2011), thesis of the University of Michigan

Liapis V., “The Thracian Cult of Rhesus and the Heros Equitans”, Kernos, 24 (2011) 95-104

Sahlins M., “Twin-Born with Greatness: The Dual Kingship of Sparta”, Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 1:1 (2011) 63–101

Sprawski S., “Early Temenid Kings to Alexander I”, in:

Roisman J. and Worthington I. (editors), “A Companion to Ancient Macedonia”, (2010) Malden, MA and Oxford, at pp. 126-44

Vickers M., “Hagnon, Amphipolis and Rhesus”, in:

Sekunda N. (editor), “Ergasteria: Works Presented to John Ellis Jones on his 80th Birthday”, (2010) Gdańsk, at pp. 75-80

Varto E. K., “Early Greek Kinship”, (2009), thesis of the University of British Columbia

Delev P., “The Edonians”, Thracia, 17 (2007) 85-106

Viapis V., “Zeus, Rhesus, and the Mysteries”, Classical Quarterly, 57:2 (2007) 381-411

Kovacs D. (translator), “Euripides: Bacchae; Iphigenia at Aulis; Rhesus”, (2003) Cambridge MA

Hammond N. G. L., “The Continuity of Macedonian Institutions and the Macedonian Kingdoms of the Hellenistic Era”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 49:2 (2000) 141-60

Hatzopoulos M.,”’L' Histoire par les Noms' in Macedonia”, in:

Hornblower S. and Matthews E. (editors), “Greek Personal Names: Their Value as Evidence: 104 (Proceedings of the British Academy)”, (2000), at pp. 97-117

Gerber D. E. (translator), “Tyrtaeus, Solon, Theognis, Mimnermus: Greek Elegiac Poetry (7th to 5th Centuries BC”, (1999) Cambridge MA

Prestianni-Giallombardo A, M, and Tripoldi B, “Iconografia Monetale e Ideologia Reale Macedone: I Tipi del Cavaliere nella Monetazione di Alessandro I e di Filippo II” Revue des Éudes Anciennes, 98 (1996) 311-55

Strassler R., “The Landmark Thucydides: a Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War”, (1996) New York

Borza E., “In the Shadow of Olympus: The Emergence of Macedon”, (1990) Princeton NJ

Hammond N. G. L. and Griffith G. T., “A History of Macedonia: Vol. II (550-336 BC)”, (1979) Oxford Raymond D., “Macedonian Regal Coinage to 413 BC", (1953) New York

Murray A. T. (translator), “Homer: Iliad, Vol. I: Books 1-12”, (1924) Cambridge MA

Smith C. F. (translator), “Thucydides: History of the Peloponnesian War, Vol. III, Books 5-6”, (1921) Cambridge MA

Smith C. F. (translator), “Thucydides: History of the Peloponnesian War, Vol. I, Books 1-2”, (1919) Cambridge MA

Svoronos J.N., “L’Hellénisme Primitif de la Macédoine Prouvé par la Numismatique

et l’Or du Pangee”, (1919) Paris