Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Alexander I: Alexander’s Coinage I

Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Alexander I: Alexander’s Coinage I

‘Signed mounted horseman octadrachm’ of Alexander (28.6 gm:catalogued by Raymond as coin 1, at p. 78)

Obverse: mounted horseman wearing chlamys (cloak) and petasus (wide-brimmed hat), carrying two spears

Reverse: ΑΛΕ/ΞΑ/ΝΔ/ΡΟ (of Alexander): inscription surrounding a quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image from Doris Raymond (referenced below, Plate III)

Alexander I (ca. 500-450 BC) was the first Argead king to be identified by inscription on his coinage (all of which was minted in silver). As long ago as 1911, Barclay Head, in his catalogue of the coins in the British Museum (referenced below, 1911, at p. 218), asserted that:

“With the possible exception of certain coins struck at Aegae (the old capital of Macedon) with the [monograms] ΑΛ, ΑΛΕ etc., there are no coins of Alexander I of an earlier date than 480 BC ...”

In her seminal catalogue (1953) of Alexander’s coinage, Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 85) asserted that:

“There is no reason for questioning the commonly accepted date of 480/79 BC for the beginning of Alexander's epigraphically or otherwise identifiable coinage.”

In other words, she:

✴differed from Head by suggesting that Alexander had been responsible for at least some of the anepigraphic coinage of the region prior to 480 BC (in addition to the subset sporting the monograms ‘ΑΛ, ΑΛΕ etc.’); but

✴agreed with him that Alexander had identified himself on his coinage after 480 BC

She argued (again at p, 85) Alexander’s aims for:

“... this first national coinage ... were that it was to be:

✴readily exchangeable with the most influential currencies of the Aegean area;

✴readily recognised as Macedonian;

✴unmistakably a regal issue.”

She started her catalogue of Alexander’s national/regal coinage with the coin illustrated above, which was identified by inscription (on the reverse) as ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟ[Y] (of Alexander).

Raymond argued (at p. 57) that:

“There can be no doubt that the coins ... [that Alexander] struck after 480/79 BC, which abandon the anonymity of the [previous period], are not the beginning of Macedonian regal currency. ... However, the date 480/79 BC is still to be taken as having some significance for Macedonian regal coinage, since it marked the freedom of Alexander from whatever form of restraint the proximity of the Persians imposed upon him .”

Before we look at the earlier anepigraphic coinage that might be attributed to Alexander, we should consider the significance of a small group of tetrobols of which Raymond was unaware, which seem to have been minted at a time when Alexander was intent upon commemorating his Persian connections.

Alexander’s ‘Persian’ Tetrobols

Tetrobol (2.38 gm.) attributed to Alexander

Obverse: Mounted horseman wearing a petasus (wide-brimmed hat) and armour, carrying a long lance in this left hand, with what is probably a Persian akinakes (short sword) clasped in this right hand

Reverse: Quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image: CNG 60 (22 May 2002), lot 250

This coin is also illustrated by Johannes Heinrichs and Sabine Müller (referenced below, at p. 306, figure 1.1)

Johannes Heinrichs and Sabine Müller (referenced below) published four silver tetrobols (standard weight 2.45 gm.) which;

✴had appeared on the market, already attributed to Alexander, in the 1990s; and

✴represented a previously unknown type.

They illustrated these coins as figure 1:1-4 (and I have illustrated their coin 1:1 above).

Tetrobol (2.18 gm.) attributed to Alexander

Obverse: Mounted horseman wearing a petasus, carrying two spears in this left hand

Reverse: Quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image from Johannes Heinrichs and Sabine Müller (referenced below, at p. 306, figure 2)

Heinrichs and Müller also illustrated the tetrabol above (their tetrobol 2) for the purpose of comparison. They pointed out (at p. 83) that, although their obverses of coins 1: 1-4 (like those of coin 2) depict a mounted horseman wearing a petasus, the horseman on tetrobol 2:

✴holds a long lance in his left hand (instead of the ‘familiar’ pair of spears of coin 2); and

✴clasps what was probably a short sword (pointing downwards) in an over-sized fist that was apparently designed to attract attention.

They observed (at p. 292) that a short sword of this type, carried on the right thigh and clasped in the right fist:

“... immediately reminds one of a Persian sword known as an akinakes", (my translation).

They also observed (at p. 284) that:

✴tetrobols 1: 1-3 came from the same pair of dies; and

✴the obverse die was also used for both tetrobol 1: 4 and tetrobol 2, although, in this latter case, the horseman’s right arm was covered by a Gewandfalte (literally, garment fold).

They suggested that the reverse die was replaced because of damage (rather than because of extensive use), and that these five coins were almost certainly issued within a short space of time, in the order: tetrobols 1: 1-3; tetrobol 1: 4; tetrobol 2.

Heinrichs and Müller argued (at p. 285) that:

✴as far as we know, the ‘akinakes’ obverse of coins 1: 1-4 was only ever used for tetrobols; whiile

✴the obverse of tetrobol 2 was shared with those of Alexander’s higher denominations, up to his tetradrachms: in fact, this obverse type was also used on Alexander’s ‘signed octadrachms’, as is evidenced by the example illustrated at the top of the page.

They suggested that:

✴a tetroblol probably corresponded to the daily rate for the soldiers and civilians that Alexander (as Xerxes’ vassal) would have been required to provide for Xerxes‘ expedition, and that ‘akinakes tetrobols’ were minted for this particular purpose’ while

✴the higher-denomination coins would have become possible only after Alexander acquired the silver mines that had belonged to the Bisaltae after the Persians withdrawal.

Thus, the ‘akinakes’ tetrobols constituted what one might speak of as an initial coinage before the start of Alexander’s subsequent ‘regular’ coinage (“Uberspitzt formuliert könnte man für Alexander I. von Makedonien von einer ersten Münzprägung von Beginn der Münzprägung sprechen”).

In short, on this model, the akinakes tetrobols belonged to an early phase of Alexander’s coinage, in which he was keen to ‘advertise’ his Persian connections. In this context, Heinrichs and Müller drew attention (at pp. 293-4 and note 58-9) to two passages from Herodotus:

✴when Xerxes arrived at Acanthus on his westward march in 480 BC, he:

“... declared a pact of guest-friendship with the Acanthians and gave them gifts of Persian clothing, praising them for the zeal with which he saw them furthering his campaign ...”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 116); and

✴during Xerxes’ subsequent retreat, when he arrived at Abdera, he:

“... made an pact of friendship with its people and gave them a golden akinakes and a gilt tiara. As the people of Abdera say (but for my part I wholly disbelieve them), it was here that Xerxes, in his flight back from Athens, first took off his belt, because he had reached safety”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 120).

They observed (at p. 294) that Alexander had made a greater contribution to Xerxes’ campaign than had either Acanthus or Abdera, and pointed out (at p, 295) that, if one assumes that he too had received the honour of a golden akinakes from Xerxes, then the ‘akinakes’ tetrobols represented Alexander himself and can be dated to 480/79 BC.

Alexander’s ‘Regal Coinage’

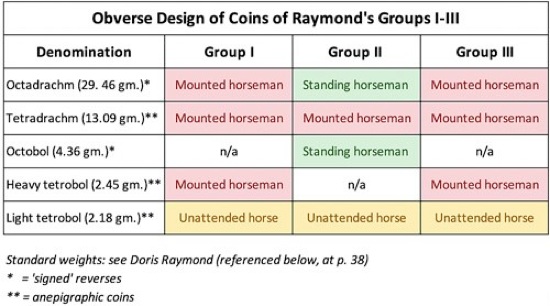

The table above summarises the structure of Raymond’s catalogue of some 130 coins from Alexander’s ‘epigraphically or otherwise identifiable coinage’, which she:

✴classified by weight/ denomination and (within each denomination) by typology/chronology; and then

✴assigned to one of three stylistic groups (Groups I, II and III above).

She then derived the dates of the transitions between groups by linking:

✴changes in the iconography adopted by Alexander; to

✴changes in the political climate in which he operated.

Selene Psoma (in Ute Wartenberg and Michel Amandry (editors), referenced below, at p. 713) observed that:

✴Alexander’s heavy coins (ca. 29 gm.):

“... are absent from hoards buried in the [Macedonian] kingdom but traveled, together with big fractions of other coinages [from this region] to Syria, Egypt, and the Levant [and also as we shall see, to even more remote places like Afghanistan”; while

✴his lighter coins (ca. 13 gm) and their smaller fractions, which circulated locally.

The heavy coins had traditionally been described as octadrachms (a practice followed by Raymond), although modern scholars generally follow Selene Psoma (as above) in designating them as tristaters. In order to retain consistency when referring to work in either camp, I use the term ‘octadrachm’ (in quotes) as an indication of a silver coin weighing about 29 gm..

We can now look at what Raymond meant by Alexander’s ‘epigraphically or otherwise identifiable coinage’: as is clear from the table above:

✴all of Alexander’s ‘octadrachms’ and octobols had ‘signed’ reverses; while

✴the other coins in the catalogue were attributed to Alexander on stylistic grounds.

In what follows, I concentrate mainly on his ‘signed octadrachms‘ because, since these were his ‘prestige coins’, their iconography and patterns of circulation potentially illuminate what is otherwise a particularly obscure period, during which the Macedonians and their Thracian neighbours adjusted first to Persian and then to Greek control. I begin with the ‘standing horseman’ coins of Raymond’s Group II because, as we shall see:

✴these belong in the wider group known as Thraco-Macedonian coinage; while

✴the ‘mounted horseman octadrachms’ of Groups I and III (discussed thereafter) can be considered to be the ‘signature’ coin of Alexander and the other early Argead kings.

Alexander’s ‘Standing Horseman’ Coinage

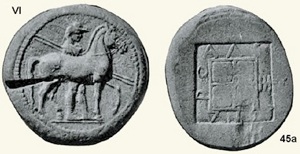

‘Signed standing horseman octadrachm’ of Alexander (29.01 gm: catalogued by Raymond as coin 45a, at p. 100)

Obverse: horseman wearing chlamys and petasus, carryings two spears and standing behind his horse

Reverse: ΑΛΕ/ΞΑ/ΝΔ/ΡΟ: inscription surrounding a quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image from Doris Raymond (referenced below, Plate VI)

Raymond began the catalogue of her Group II coins with 14 ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ of 13 types (numbers 45-57, at pp. 100-1), the first of which is illustrated above. There was no major change in the tetradrachms from those of Group I. However, she noted (at p. 109) that:

“... the heavy tetrobols [of Group I had been replaced by] a unique issue of octobols [see the table above].

Her Group II coinage comprised 23 octobols (of 10 types), which she catalogued as her coins 66-75 (at pp. 103-4) and illustrated on Plate VII. As noted above, these were the only coins, other than his ‘octadrachms’, that Alexander ‘signed’: in fact, their iconography was essentially identical to that of his ‘standing horseman octadrachms’, and Raymond reasonably assumed these two ‘standing horseman’ denominations had been introduced at the same time.

Raymond noted that the substitution of the heavy tetrobols of Group I by the octobols of Group II would have:

“... made the exchange between Attic and Macedonian currency a simple affair, for:

✴the octobol was the equivalent of an Attic drachm;

✴the light tetrobol was in weight an Attic triobol; and

✴the tetradrachm of 13.09 gm., was of the worth of three Attic drachms.

The octadrachms, which were not readily exchangeable with Attic currency, were nevertheless retained, even though their fraction, the heavy tetrobol was intermitted. The reason, I think, is not far to seek: Alexander [apparently still] needed to make [high value] purchases [from his neighbours] in the north ...”

Thus, in order to date the start of her Group II, Raymond now needed to find a set of circumstances in which Alexander might have replaced:

✴the ‘mounted horseman’ of the obverses of his earlier ‘signed octadrachms’ by the ‘standing horseman’ design; and

✴the earlier heavy tetrobols by octobols, in order to facilitate economic exchanges with the Athenians.

It will be useful to look at the change in the iconography of the ‘octadrachms’ in a the context of the wider Thraco-Macedonian coinage, before looking at the wider political developments that might have conditioned the economic relations between Alexander and Athens.

Thraco-Macedonian Coinage

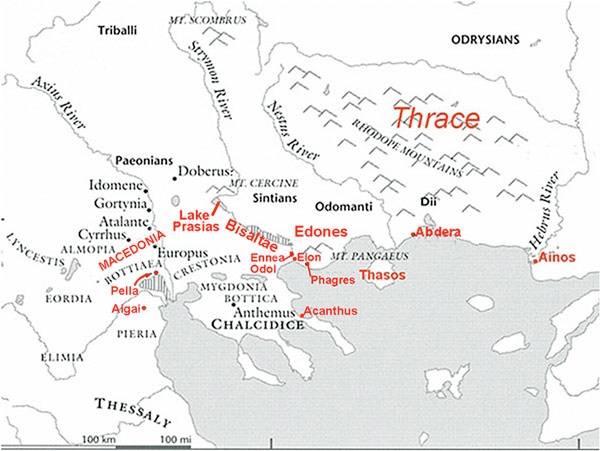

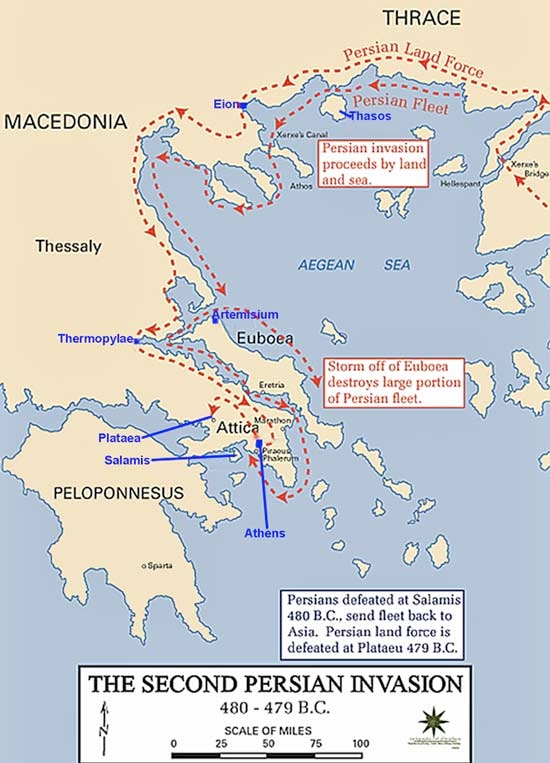

Ancient Macedonia, Thrace and Northern Greece

Image = detail from Robert Strassler (referenced below, Map 2:97, at p. 318), my additions in red

Alexander’s ‘octadrachms’ belong to a group of heavy silver coins from the region that Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 347) characterised as the:

“... large, almost ingot-like coins of the Thracian and Macedonian kings and [tribes, which] have always held a fascination for historians and numismatists alike.”

In a later paper (referenced below, 2021, at p. 58), she observed that:

“In the early 5th century BC, there are clearly some common features on coins of the various tribes [of Thrace, ... [It] is also worth mentioning that the Macedonian coins of Alexander I are closely associated [with this Thracian] coinage] through their iconography, which begs the question whether a ‘Thracian’ identity can be really clearly differentiated from a Macedonian one.”

These heavy Thraco-Macedonian coins part of what Martin Price (referenced below, at p. 43) described as:

“... an explosion of coinage [that occurred in northern Greece] in the early 5th century, ... [when] silver coinage was a relatively new phenomenon”, (my changed word order).

He suggested (at p. 43) that this ‘explosion’ might have occurred as a result of improvements in the technology for extracting silver from lead ores (perhaps linked to increasing contacts with Persia), which had intensified the search for accessible silver reserves. He:

✴observed that the Athenians had played a key part in these developments by virtue of their exploitation of the silver mines at Laurion in southern Attica, which had started during the tyranny of Pisistratus in the mid-6th century BC); and

✴noted (at p. 44) that:

“The reason why [the so-called Thraco-Macedonian region] plays such a prominent part in the history of the coinage [of this period] is that the area was [similarly] rich in silver mines.”

The silver for Alexander’s coinage almost certainly came from the mines near Lake Prasias, which was in the neighbouring territory of the Thraco-Macedonian tribe of the Bisaltae, while their neighbours to the east had access to the silver mines of Mount Pangaeus.

Raymond: Precursors to Alexander’s Group II ‘Octadrachms’

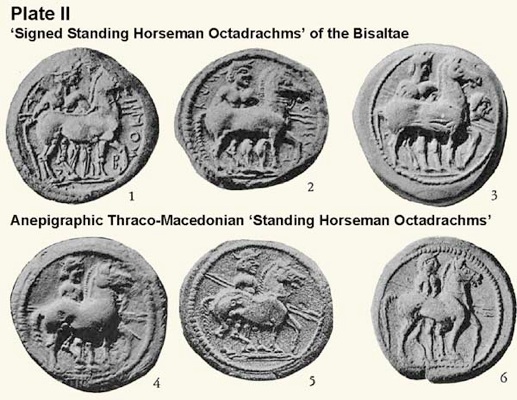

Extract from Doris Raymond (referenced below, Plate II: coins identified at p. 167)

All of these coins share the following characteristics:

Obverse: naked horseman wearing a petasus, carrying two spears, standing behind his horse

Reverse: quadripartite square within an incuse square

Coins 1-3: the ethnic of the Bisaltae is inscribed on the obverse

Coin 3: symbol of the bearded head of Silenus in front of the horse

Coins 4-6: anepigraphic obverse; rump of the horse has (or possibly has) traces of a ‘brand’ of the symbol of the caduceus

As noted above, Raymond (at p. 57) argued that Alexander had issued anepigraphic ‘octadrachms’ prior to 480/79 BC, when he introduced his ‘signed mounted horseman octadrachms’. More specifically, she began her account of the Macedonian coinage of this earlier period (at p. 48) with the observation that:

“It does not lie within the scope of this study to investigate in detail the issuing agents of the mass of [Thraco-Macedonian] tribal coinage. However , two groups of coins that show a clear relation to the regal Macedonian issues ... will be seen:

✴to be the precursors of Alexander's coins; and

✴to furnish an explanation for the variety of his coin-types.

They are:

✴the goat staters of Aegae [which are not relevant to the present discussion]; and

✴certain octadrachms ...[with obverses depicting a] horse and attendant [= my ‘standing horseman’] ... ”

She discussed these ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ at pp. 53-9 and illustrated them as coins 1-6 on her Plate 2 (reproduced above).

Coins 1-3 (‘Signed’ on the Obverse by the Bisaltae)

She started by observing (at p. 53) that:

“The octadrachm type is always a horse with attendant holding the reins and two spears ... One variant of the type, ... [which] nearly always bears the Bisaltian ethnic [on the obverse is illustrated at PLATE II, 1-3, [see the illustration above].”

She identified these three coins (at p. 167) as follows:

✴coin 1 (Paris, BT, I, 2, 1489);

✴coin 2 (London, BMC Macedonia, p. 140, 2); and

✴coin 3 (Hunterian Collection I, p. 268, 2)

She did not catalogue them, but they were all subsequently included in the catalogue of Thraco-Macedonian coins published by Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below):

✴Raymond coin 1 = Tzamalis coin 13 (28.88 gm.), at p. 85;

✴Raymond coin 2 = Tzamalis coin 39 (27.42 gm.), at p. 92; and

✴Raymond coin 3 = Tzamalis coin 63 (28.51 gm.), at p. 99.

Raymond seems to have believed that coins 1 and 2 dated to 492-480/79 (see below). In relation to coin 3, she argued:

✴at p. 53) that:

“The style of [these three] coins improves considerably, culminating in the piece in the Hunter Collection (PLATE II, 3 )”; and

✴(at p. 110) that the Bisaltian coin 3, which is:

“... of the same type [as Alexander’s ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ in Group II] must be dated by its style to this same time.”

In short, she suggested that:

✴the type of the Bisaltian coins 1-2 had pre-dated Alexander’s ‘mounted horseman octadrachms’ of her Group I; while

✴the type of the Bisaltian coin 3 had been issued in parallel with Alexander’s ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ of her Group I.

Coins 4-6 (Anepigraphic)

As we have seen, the next three coins on Raymond’s Plate II were anepigraphic ‘standing horseman octadrachms’:

✴coin 4 (A. M. Newell Collection), which Tzamalis catalogued as coin 112, at p. 108;

✴coin 5 (Weber Collection, 1847), which Tzamalis catalogued as coin 131, at p. 113; and

✴coin 6 (Boston, Warren Collection 554) which Tzamalis catalogued as coin 125, at p. 111.

Again, Raymond did not catalogue them, but they were all later included in the catalogue of anepigraphic coins attributed to either Alexandre or the Bisaltae published by Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below):

✴Raymond coin 4 = Tzamalis coin 112 (27.92 gm.), at p. 108;

✴Raymond coin 5 = Tzamalis coin 131 (28.64 gm.), at p. 113; and

✴Raymond coin = Tzamalis coin 125 (28.47 gm.), at p. 111.

Raymond argued (at p. 55) that all of these anepigraphic types should be attributed to Alexander:

“In spite of the fact that the [‘standing horseman obverse’] does not appear on Alexander's ‘octadrachms’ before Group II:

✴the close association of the [anepigraphic ‘octadrachms’] with those of Group I is self -evident; [and]

✴... the caduceus as brand, which appears on some of the [anepigraphic] ‘octadrachms’, also occurs on some of Alexander's ‘octadrachms’ [see above].

That these [anepigraphic ‘octadrachms’] are Macedonian (rather than Bisaltian) cannot be [denied]”.

Raymond argued (at p. 56, on stylistic grounds) that:

“Various factors indicate that [the anepigraphic coins 4-6, which she attributed to Alexander] should be dated rather late in the series of tribal issues. ... It must be concluded that Macedonia ... did not join the [putative Thraco-Macedonian] monetary alliance of the tribes until rather late.”

Raymond’s Conclusions on the Precursors to Alexander’s ‘Group II ‘Octadrachms’

Raymond thus concluded that:

✴before her Group I:

•the Bisaltae issued ‘standing horse octadrachms’ which they ‘signed’ on the obverse; and

•shortly before the start of Group I, Alexander issued anepigraphic versions of them;

✴during her Group I:

•the Bisaltae continued to issue their ‘standing horse octadrachms’; and

•Alexander issued ‘mounted horseman octadrachms, which he signed on the reverse; and

✴during her Group II:

•the Bisaltae continued to issue ‘signed standing horse octadrachms’ (evidenced by coin 3); and

•Alexander issued ‘standing horseman octadrachms, which he also signed on the reverse.

Historical Context of Raymond’s Group II ‘Octadrachms’

Phase I: Period Prior to the Group I Coinage

We should start with Raymond’s assertion (at p. 57) that the start of Alexander’s Group I coinage:

“... marked the freedom of Alexander from whatever form of restraint the proximity of the Persians imposed upon him.”

The implication is that the Bisaltian and anepigraphic ‘octadrachms’ exemplified as coins 1-6 above had first been issued during the period in which both the Bisaltae and Alexander had been subservient to the Persians. This leads us to look at the evidence for this period that can be gleaned from our surviving sources.

We first hear of contact between that Persians and the Macedonians in 510 BC, when, according to Herodotus, the Persian general Megabazus (having subjected the Paeonians of northern Macedonia on the on the orders of King Darius the Great and sent them to Phrygia, which had apparently been their original homeland):

“... sent [seven] messengers ... to [the court of King Amyntas II, Alexander’s father] to demand earth and water for [i.e., submission to] Darius the king”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 17: 1).

Although Herodotus’ account of the ambassador’s dealings with Amytas and Alexander at this time is almost certainly apocryphal, there is good evidence (see below) that, at about this time, Amyntas arranged a diplomatic marriage between Gygaea (his daughter and Alexander’s sister) and the Persian commander Bubares (see, for example, Carol King, referenced below, at p. 26). We know nothing about Persian-Macedonian relations in the three decades after 510 BC: Darius sent the general Mardonius to secure the north Aegean coast in 492-490 BC (by which time Alexander had succeeded his father), but Alexander does not feature in the surviving accounts of this short Persian campaign, which ended with the Athenians’ famous victory at the Battle of Marathon (490 BC).

Despite this lack of relevant sources, Raymond argued (at p. 58) that:

“The activities of the Persians in the Thraco-Macedonian area [in 492-490 BC] must have inclined [the tribes of the region], which had long [shared a] monetary convention, to a greater common effort. When the Macedonians came in contact with the Persians (inamicably, as we see from Herodotus), the occasion arose for them to unite to some degree with the other tribes, from whom they had hitherto held themselves aloof ... “

She was more explicit about this hypothesis when she looked back (at p. 118) to:

“... the old inter-tribal co-operation ... , which, in the years of the Persian advance, notably 492 BC and following, had become a military alliance, [although] probably only for defensive purpose.”

This was the basis upon which she argued (at p. 58) that:

“When, suddenly, the Macedonians began [issuing anepigraphic ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ shortly before 480 BC], ... it is safe to conclude that a common military danger had compelled them to participate in [a military] alliance, ... the only historical record [of which ] exists in the coins themselves.”

This is an extremely rash conclusion to draw on the basis of an analysis of only six coins. It is certainly true (noted above) that the wider coinage of the region does indeed suggest the existence of shared monetary conventions that continued into the early 5th century BC. However:

✴there is no surviving evidence that the Thraco-Macedonian tribes ever formed an anti-Persian military alliance (even for defensive purposes); and

✴since Alexander’s sister was securely married into the Persian nobility by this time (see below), it is most unlikely that he would have joined such an alliance, even if it had existed.

This early problem with Raymond’s analysis is important because, as we shall see, she predicated key parts of her subsequent analysis on Alexander’s alleged revival of this alleged Thraco-Macedonian military alliance.

Phase II: Period of the Group I Coinage

Image from Wikipedia (my additions in blue)

Our sources improve in 480 BC, when King Xerxes (Darius’ son and successor) advanced along the northern Aegean towards Greece, intent upon the subjugation of Athens. According to Herodotus, in this initial phase of the campaign:

“[The Persians’] fleet subdued the Thasians, who did not so much as lift up their hands against it; their land army added the Macedonians to the slaves that they had already (for all the nations nearer to them than Macedonia had been made subject to the Persians before this)”, (‘Persian Wars’, 6: 44).

Herodotus (at ‘Persian Wars’, 7: 185) also included Macedonia among the ‘nations’ of this region that supplied military support to the Persians.

As Carol King observed (at p. 27) observed:

“... until the arrival of Xerxes in 480 BC, there is no mention of a Persian overseer in or responsible for Macedonia. ... [Alexander’s subservience] to Persia is clear, but the nearest Persian garrison was possibly the one under the hyparchos (governor) Boges at Eion, at the mouth of the Strymon.”

However, in his account of Xerxes return march towards the end of the year (see below), Herodotus recorded that:

“It was then that a monstrous deed was done by the Thracian king of the Bisaltae and the Crestonian territory. He had refused to [become] Xerxes' slave, and fled to the mountains called Rhodope. He had also forbidden his sons to go with [Xerxes’] army to Hellas, but they had ... followed the Persians' march. For this reason, when all the six of them returned unscathed, their father tore out their eyes”, (‘Persian Wars’, 8: 116).

This suggests that, unlike Alexander and most of the leaders of the Thracian tribes, the [unnamed] king of the Bisaltae had refused to support Xerxes and had, instead, fled inland until the danger had passed.

Having traversed the northern Aegean coast, Xerxes also traversed the coast of Thessaly, apparently unopposed.

As we have seen, Raymond argued (at p. 57) that Alexander’s Group I coinage:

✴began in 480/79 BC; and

✴marked his freedom from

“... whatever form of restraint the proximity of the Persians [had] imposed upon him.”

She added (at p. 85) that:

“Whether [these] coins appeared first after Salamis or after Plataea, it is impossible to determine. The sophisticated complexity of Alexander's [Group I] issues can only be the result of a carefully thought-out plan; his use of types and denominations shows clearly that ... his own octadrachms, tetradrachms and fractional issues in the [putative] monetary alliance [with the Bisaltae - see above] were [now inadequate] for his purposes. In this first national coinage, three aims were embodied:

✴it was to [continue to] be readily exchangeable with the most influential currencies of the Aegean area; but

✴it was [now also] to be:

•readily recognised as Macedonian; and

•unmistakably a regal issue.”

Raymond presumably suggested here that last two ‘aims’ were largely achieved by the introduction of the new ‘mounted horseman’ iconography for the ‘octadrachms’ (although it is odd that she did not draw specific attention to the equally innovative new reverse design). More fundamentally, there does not seem to be that anything in our surviving sources that implies that the Persians had imposed any restraint on Alexander’s ability to express his regal status within his kingdom and throughout the surrounding region: indeed, before Plataea, his status would have been enhanced by the facts that:

✴his sister was married into the Persian nobility: and

✴both the Persians and the Athenians held him in high esteem.

On the other hand, after Plataea, he felt that he needed to remind the Athenians of the desperate (and treacherous, if not fictitious) deed that he had done ‘for the sake of Hellas’.

Phase III: Period of the Group II Coinage

Raymond:

✴began her catalogue of her Group II coins with 14 ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ of 13 types (numbers 45-57, at pp. 100-1), the first of which (coin 45a) is illustrated above; and

✴noted (at p. 110) that:

“The type of the ‘octadrachms’ is once again the [standing horseman] of the anepigraphic octadrachms issued in the late 6th (?) and early 5th centuries BC [see above]. At least one Bisaltian ‘octadrachm’ of the same type [= her coin 3, illustrated on Plate II and discussed above] must be dated by its style to [the] same time [as Alexander’s Group II coins]. The retention of Alexander's name on the reverse shows that he was [no longer] merely a participant in the [putative] alliance [with the Bisaltae] as he had been [before 480 BC], but [was now] its leader.”

Raymond also catalogued 23 octobols of 10 types (numbers 66-75, catalogued at pp. 103-4 and illustrated on Plate VII) and placed them all in Group II because they shared their iconography with the ‘octadrachms of this group (see her ‘BASIC TYPE B’ at p. 68 and ‘BASIC TYPE AA’ at p. 69). Interestingly, these octobols were the only coins of Alexander, apart from his ‘octadrachms’, that that he ‘signed’. She pointed out (at p. 109) that the denomination change represented by this group of coins was profound:

“... the heavy tetrobols [of Group I have been replaced by] a unique issue of octobols. This substitution [would have] made the exchange between Attic and Macedonian currency a simple affair, for:

✴the octobol was the equivalent of an Attic drachm;

✴the light tetrobol was in weight an Attic triobol; and

✴the tetradrachm of 13.09 gm., was of the worth of three Attic drachms. The octadrachms, which were not readily exchangeable with Attic currency, were nevertheless retained, even though their fraction, the heavy tetrobol was intermitted. The reason, I think, is not far to seek: Alexander [apparently still] needed to make [high value] purchases [from his neighbours] in the north ...”

Raymond now needed to find a set of circumstances in which Alexander might have:

✴emerged as the head of the (putative) revived alliance with the Bisaltae; and

✴had a particular reason to establish new economic ties with Athens.

The problem was that, as she observed (at p. 108):

“The knowledge that we possess of the kingdom of Macedonia under Alexander after the defeat of the Persians is very scanty: actually, [it is] not so much knowledge as inference . The events of the [50 years between the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars, (478–431 BC)], as recorded by Thucydides, do not include any action by Alexander.”

However, she argued (at p. 108) that it was still possible to hypothesise that the events that had led Alexander to issue his Group II coins had coincided with:

“... the earliest action of the Delian Confederacy and the [subsequent] reduction of Eion by [the Athenian commander] Cimon [in 476 BC: since Eion] is close to Macedonia, we may be sure that Alexander was concerned in [this anti-Persian action]”.

In order to ‘unpack’ this hypothesis, we need to look in more detail about what we do know about the events of the three or four years between the Athenians victories at Plataea and Eion.

Since Cimon’s conquest of Eion probably took place in 476 BC, this was the date that Raymond adopted for the start of her Group II, arguing (at p. 109) that the changes that took place in Alexander’s coinage at this point signalled his:

“ ... alacrity ... to assist the Athenians [drive the Persians further eastwards]. ... The changes in denomination, type and style of the coins of Group II show that it began as an issue designed:

✴to exchange readily with Athenian currency;

✴to rally the moribund, if not defunct, tribal alliance to work with the forces of the [new Athenian alliance]; and

✴to provide an earnest of Alexander's membership in the Hellenic race.”

Raymond (at p. 118) then set out in more detail the part that she envisaged for Alexander in the capture of Eion. She argued that:

“From the coins, it seems that Alexander was reviving some portion at least of the old inter-tribal co-operation of the 6th century BC, which, in the years of the [initial] Persian advance [into Thrace], ... had become a military alliance (probably only for defensive purpose). He succeeded in influencing the Bisaltae ...and possibly even the Edones, to unite. [Since] these latter ... lived a little above Eion on the Strymon, they would be concerned with Athenian action so near home.”

From this, it seems that Raymond envisaged that Alexander had:

✴formed an alliance with a number of Thracian tribes, including the Bisaltae and (possibly) the Edones, and that this alliance had assisted Cimon and the allies of the Athenian League in expelling the Persians from Eion in ca. 476 BC; and

✴introduced his Group II coinage shortly thereafter, in order to:

✴draw attention to his new position at the head of the (putative) revived alliance of Thraco-Macedonian tribes; and

✴facilitate the increase in trade with Athens that could be expected in the new political climate.

Plutarch (in the 2nd century AD) was responsibly for the most detailed surviving account of Cimon’s conquest of Eion:

“First he defeated the Persians themselves in battle and shut them up in the city; then he expelled from their homes above the Strymon the Thracians from whom the Persians had been getting provisions [and] put the whole country under guard. [Finally], he brought the besieged [at Eion] to such straits that [Boges, the Persian general in command there], gave up the struggle, set fire to the city, and destroyed with it his family, his treasures, and himself”, (‘Life of Cimon’, 7:2).

We can reasonably agree that:

✴Alexander, the ‘friend and benefactor of Athens’ (who already marked one alleged victory over the Persians with a statue at Delphi); and

✴the famously anti-Persian Bisaltae;

would have wished to see the Persians expelled from Eion, perhaps to the extent of providing resources for, or even participating in, Cimon’ attack. However, we cannot be sure that the Edones would have felt the same way: after all, Plutarch (see above) had noted that:

“ Cimon defeated the Persians themselves in battle and shut them up in the city; then he expelled from their homes above the Strymon the Thracians from whom the Persians had been getting provisions, [and] put the whole country under guard ...”

Peter Delev (referenced below, at [pp. 21-2]) argued that:

“The identification of [Plutarch’s] ‘Strymonian Thracians’ in the vicinity of Eion with the Edones, although not explicit, seems quite probable, and the events in 476 BC must have set a bad start to their subsequent relations with the Athenians.”

In short, although it seems likely that the Edones were involved in the hostilities at Eion, it is far from certain that they were on the side of Cimon and the Athenian League. (I return to the coins of Getas below).

John May on the Introduction of the ‘Octadrachms’ of Group II

‘Signed tetradrachm’ (14.5 gm.) of Abdera, issued by the magistrate Phittalos

Type catalogued by John May (referenced below, at pp. 122-3) as the first in his Period IV

Obverse: Seated griffin (civic symbol of Abdera), with a scarab beetle (symbol of Phittalos) below its raised right leg

Reverse: ΕΠΙ/Φ ΙΤΤ/ΑΛ/Ο (in the time of Phittalos);

inscription surrounding a raised quadripartite square, all within an incuse square

Image from Numista: type illustrated by John May (referenced below) at Plate VIII, coins 126-9

Raymond was remarkably uninterested in the development of the ‘new’ reverse design between Group I and Group II: she simply noted (at p. 111-2) that:

“A comparison of Plates III, IV and V with Plates VI, VII,VIII and IX will show clearly the great improvement in style in Group II. Since, [in chronological termsm Group II] follows immediately upon Group I, the change must be due to a fresh artistic impulse, for the origin of which it is natural to look to the south [i,e., Athens]. The greater skill in the execution of the dies is more readily apparent on the octadrachms and tetradrachms ... Since the reverses of the octadrachms offer an opportunity for little more than fine letter cutting, only the obverses need be considered.”

Some 8 years after the publication of Raymond’s catalogue, John May completed a catalogue of the coinage of Abdera (which was published posthumously in 1966, as referenced below). He broadly followed Raymond’s approach, but his coins (which had been minted over a much longer period) were split into nine successive chronological groups that extended from ca. 54o to 345 BC. He used the emergence ‘new’ reverse design to mark the start of his Group IV: the first of these (illustrated above) contained the ‘signature’ of Phittalos, who is generally assumed to have been the magistrate responsible for its issue.

May, who was apparently convinced by Raymond’s dating of the start of Alexander’s ‘signed’ coinage to 480 BC, concluded that:

“... the honour [of originating the the new reverse design] must rest with Alexander or, possibly, Acanthus ”

He suggested (at note 20) that:

“The introduction of this style of reverse at Abdera comes very little later than that at Acanthus, where Desneux [referenced below] suggested the date ca. 480 BC for its introduction, which seems from an overall consideration of the Acanthian coinage to be rather too early.”

He also argued that the ‘very rough work’ of the reverses of Raymond’s Group I would not have inspired an independent Hellenic mint like that of Acanthus to adopt this design, and argued that it was:

“Much more likely [that] the first Macedonian octadrachms that are truly in the style [later] adopted by Acanthus and Abdera [are those of Raymond’s Group II], which are assigned with fair probability to ca. 476/5 BC.”

In short, on his model:

✴Alexander:

•introduced the new reverse type on his ‘signed mounted horseman octadrachms’ of ca. 480 BC; and

•refined the design for his ‘signed standing horseman octadrachms’ in ca. 476/5 BC;

✴followed in quick succession by:

•Acanthus, with the issue of Desneux’s tetradrachm 93, the first to be signed AKANΘION; and then

•Abdera, with the issue of the ‘signed’ tetradrachms issued ‘in the time of Phittalos’.

A Second Phase in Raymond’s Group II (ca. 465 BC)

‘Standing horseman octadrachm (29.00 gm.: catalogued by Raymond as coin 55a, p. 101

Obverse: horseman wearing chlamys and petasus, carrying two spears and standing behind his horse:

waning moon behind his head

Reverse: ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟ: Inscription surrounding quadripartite square within an incuse square

Part way through her account of the ‘chronology and significance’ of the coins in Group II, Raymond turned (at p. 119) to the event of 465 BC, when:

“... the Athenians sent out 10,000 colonists ... to found a colony at Ennea Hodoi, on the Strymon, [which was] in Edonian territory. ... [Thucydides recorded that], after conquering at Ennea Hodoi, [the Athenians continued] inland and were utterly defeated by all the Thracians at Edonian Drabescus.”

There is no surviving evidence that Alexander played any part in this stunning victory over the Athenians. However, Raymond argued (at p. 120):

“That Alexander was the prime mover is to be seen from the coins. The latest of his [Group II] octadrachms [coins 54-7 - see the illustration of coin 55 above] carry (in the upper left field) the unusual symbol of the waning moon. This I take to be Alexander's way of making known his sentiments towards the Athenians, who were at Thasos conducting a siege for 2-3 years after Drabescus. It was the symbol [that the Athenians] had used to mark their defeat of the Persians, interlopers into their world. Alexander [now] used their own symbol to mark their defeat as interlopers into his world.”

The point here was that the Athenians, who had faced a devastating invasion by Xerxes in 480 BC, had:

✴had avenged this by playing a major role in the Greeks’ victories over the Persians at Salamis and Platea in 480/79 BC; and

✴introduced a new series of silver ‘owl’ tetradrachms in which:

•a victory wreath of olive leaves was added to Athena’s helmet on the obverse; and

•a crescent moon was added behind the neck of the traditional owl (the civic symbol of Athens) on the reverse;

possibly in order to commemorate the part that they had played in expelling Xerxes from the northwestern Aegean.

I return to the Athenian precedent below.

Raymond thus asserted (at p. 120) that:

“... the [waning moon] symbol on the octadrachms is to be dated after 465 BC, but how much longer the issue lasted is quite indeterminable .”

She then set out (at pp. 122-3) her model for the coinage of the last phase of her Group II:

“In 476/5 BC, the issue was begun with octadrachms (without the moon ), tetradrachms ... , octobols and both series of light tetrobols ... About the time of the Thasian revolt (466/5 BC) and the coming of the 10,000 settlers [to Ennea Hodoi], perhaps shortly before that time if Alexander the issue of octobols ceased ... After Drabescus (465 BC), the waning moon was added to the octadrachms . The terminal date cannot be reached from consideration of such evidence as we now possess . The conjectured date of 460 BC is merely a suggestion, based partly on the small size of Group III. It is quite possible that Alexander struck no coins at all for some years following the waning moon octadrachms . When the Athenians retired from the north after the subjection of the Thasians [in 463/2 BC], the country may have been quiet and the currency already in circulation sufficient for local needs”

In other words, Raymond suggested that, as Alexander became increasingly disillusioned by the Athenians from ca. 465 BC, he:

✴first continued with Group II, but:

✴ceased issuing his ‘octobols’, which he had introduced to facilitate his trade with Athens; and

✴introduced the ‘waning moon’ symbol to his Group II ‘octadrachms’ in order to signal his disillusionment to the Athenians; and then

✴finally, ca. 460 BC(perhaps after a period when he ceased to issue new coin types), he initiated Group III, in which he reverted to the original ‘mounted horseman’ obverse for his ‘octadrachms’, thereby signalling his renewed independence.

Precedent from the Athenian ‘Waning Moon’ Tetradrachms

As we have seen, Raymond argued (at p. 120) Alexander’s issue of ‘waning moon octadrachms’ from 465 BC (the time of the rout of the Athenians at Ennea Hodo)i, constituted:

“... Alexander's way of making known his sentiments towards the Athenians ... It was the symbol that they had used to mark their defeat of the Persians, interlopers into their world. Alexander [now] used their own symbol to mark their defeat as interlopers into his world.”

The problem with this is that, although the new Athenian tetradrachms were clearly ’victory coins’, this characterisation was not predicated on the crescent moon on their reverses: as Colin Kraay (referenced below, 1956, at pp. 56-7) observed, the wreath that had been newly added to Athena’s helmet on the obverses:

“... can be reasonably interpreted as a sign of victory ... [By] itself, this affords no means of choosing between:

✴[the Greeks’ victory at] Marathon [in 490 BC];

✴[their victory at] Salamis, or indeed

✴ victory over the Persians in general.

A recent study has shown that [a waning moon] is applicable to ... [the Persians’ defeat at] Salamis rather than Marathon, and therefore (if this argument is correct) the wreath and crescent must have been added in or after 480 BC. But, plausible as this argument is, it may still be invalid through reading too much into this lunar symbol. Apart from its insignificance and its restriction to the tetradrachm, it must be remembered that a moon has to be shown as a crescent if it is to be recognisable. ... Although the association of the moon with Salamis may be correct, it is at best uncertain and affords no secure foundation for chronology.”

In a more recent discussion of these coins, Lisa Kallet and John Kroll (referenced below, at pp. 17-8 and Figure 2.4) accepted Kraay’s analysis, observing that, with the Persian threat at an end the earlier tetradrachms:

“... were rendered with much greater refinement and an added detail: the brow of Athena’s helmet was now embellished with a row of olive leaves as a kind on victory wreath.”

They made no mention of the crescent moon on the reverse (albeit that they recorded its existence on the inscription under Figure 2.4).

It therefore seems that, although we can reasonably assume that the ‘waning moon’ on the late ‘octadrachms’ in Raymond’s Group II were inspired by the Athenians’ ‘waning moon’ tetradrachms and thus post-dated 479 BC, we have no basis for assuming that they commemorated the rout of the Athenians at Drabescus in 465 BC (and thus no evidence of any kind that Alexander played any part in these events)

Peter Delev (referenced below, at [p. 25]) pointed out that there are many discrepancies between the various surviving accounts of this momentous turn of events. However, he observed that:

“Wherever the [rout of the Athenians] really took place, the main events of 465 BC [are beyond] question: the Athenians had attempted a major advance in the Strymon area, and this was dramatically thwarted by the Edones, costing the lives of most or all of the 10,000 Greek colonists. In a recent development of our knowledge on one important source of information - the silver coins abundantly minted in the region in the late 6th and earlier 5th century BC - it now seems possible to identify the king of the Edones who won this great battle. This would have been Getas, known from a series of heavy silver coins bearing different versions of the inscription ‘Getas, king of the Edones’.”

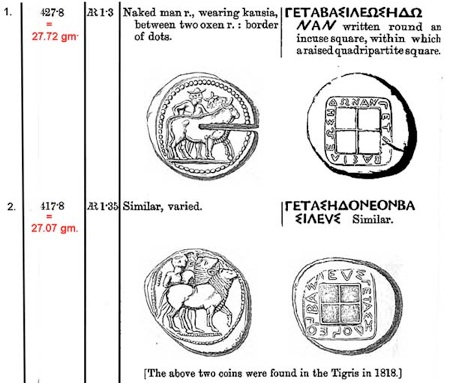

Raymond on the Evidence from the Edonian Coinage

Catalogue entry by Barclay Head (referenced below, 1879, at p. 144)

for the coins of Getas, King of the Edones in the British Museum

Raymond argued (at p. 118) that her hypothesis that the Edones had joined Alexander and the Bisaltae in her putative anti-Persian alliance:

“... is enhanced by the form of the letters on some of their ‘octadrachms’. [The obverse of these] coins shows two oxen and an attendant: the type is thus similar to the ‘standing horseman’ used:

✴always by the Bisaltians, with the ethnic on the obverse:

✴... [before 480 BC] by the Macedonians, without an inscription; and

✴only here [in Group II], with Alexander's name.

The form of the A in the inscription on the reverse ΓΕΤΑ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΗΔΩΝΑΝ [(Getas, basileus (king) of the Edones)] is the one that:

✴displaced the [archaic alpha] shortly after 479 BC on Macedonian coins and various others in that area; and

✴is used on the coins of Acanthus [cited at note 19 as Desneux 90-92, that were] first inscribed at this time. [Note that these were the last three tetradrachms before Desneux’s Period II, which began with the introduction of the ‘new’ reverse that had the inscription AKANΘION surrounding a quadripartite square within an incuse square (see Desneux 97, illustrated above)

... It seems fair to conclude that Getas was a ruler of the Edones contemporary with Alexander, who took part in the renewal of the old alliance revived to give assistance to the [Athenian] League when its contingents moved [on Eion].”

The Edonian coins to which Raymond referred (see her note 18) were those catalogued by Barclay Head in the entries illustrated above: the note at the end of this entry indicates that they formed part of the so-called Tigris Hoard (IGCH 1762, 1816), which was discovered on the banks of the Tigris, some 65 km south of Ctesiphon (in modern Iraq). Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at pp. 327-8) observed the uncertainties that surround this hoard limit is value as a source of chronological evidence.

Kabul Hoard (IGCH 1830)

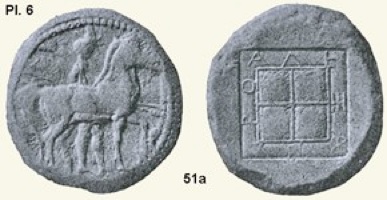

‘Signed standing horseman octadrachm’ of Alexander (28.64 gm.: Raymond coin 51a, at p. 101)

Obverse: horseman wearing chlamys (cloak) and petasus (wide-brimmed hat), carrying two spears,

standing behind his horse: horse’s rump ‘branded’ with head of a caduceus; hound leaping up in front of it

Reverse : ΑΛΕ/ΞΑ/ΝΔ/ΡΟ (of Alexander), surrounding a quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image from Doris Raymond (referenced below, Plate VI)

Alexander I (ca. 480-450 BC) was the first Argead king to be identified by inscription on his coinage, all of which was minted in silver. In her seminal catalogue of his coinage (and that of his son, Perdiccas II), Doris Raymond (referenced below, 1953, at p. 65, note 5) observed en passant that:

“The two most recently appearing Alexander octadrachms [are] from a hoard found in Afghanistan and published in ‘Mémoires de la Délégation Archéologique Française in Afghanistan’ , XIV.

She noted that, at her time of writing, both of these coins were in private collections:

✴she was unable to see one of them, which she believed was in the Pozzi Collection (which I think that it was Pozzi 815, which apparently used the same dies as CNG Triton XXVII, (27 October 2018) lot 42); but

✴she was able to examine and catalogue the second, which was in the the Lambe Collection (see her coin 52, see p. 101).

She did not illustrate this second coin, although she noted that:

✴it shared its reverse die with her coin 51a (illustrated and above); and

✴the two obverses were almost identical.

Raymond:

✴observed (at p. 26):

“... that many of the early [Thraco-Macedonian’ coins (and even those of Alexander) [that are] found in hoards in remote lands are slashed or otherwise disfigured. [This] can be taken to mean that these coins, [which were obviously accepted locally] at face value, were only accepted abroad after being weighed and tested for purity”; and

✴added (at note 22) that:

“Many [of these hoards in remote lands] have been found in Egypt and Mesopotamia. The most remote find appears to be that in Afghanistan [which is about to be] published by Daniel Schlumberger in ‘Mémoires de la Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan’, XIV ... This information was kindly supplied to me by the author ... while the book was in press. I am unable to give the page numbers because I have not seen the volume.”

It is not clear (at least to me) how much information Raymond had received from Schlumberger, but I assume that he had alerted her to the existence and provenance of the ‘two most recently appearing Alexander octadrachms’.

This was Raymond’s only reference to a specific hoard as the original provence of a coin signed by or attributed to Alexander, even though she

Like Raymond, I have been unable to consult Schlumberger’s publication (although it is referenced below). However, according to this excellent page from Wikipedia, this hoard:

✴“... was discovered by a construction team in 1933 when digging for foundations for a house near the Chaman-i Hazouri park in central Kabul. According to the then director of the Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan (DAFA), the hoard contained about 1,000 silver coins and some jewellery. 127 coins and pieces of jewellery were taken to the Kabul Museum and others made their way to various ... [museums and private collections].”

Unfortunately, the Kabul Museum was looted in 1993, and it is entirely possible that many of the stolen coins have since re-emerged on the market.

Kenneth Jenkins, in this review of Schlumberger’s paper, noted that the discovery of this hoard in 1933 marked:

“... the first [occasion on which] a number of Greek coins from the Mediterranean area have been found beyond the Hindu Kush. These coins are:

✴about 30 pieces of Aegina, Melos, Corcyra, Acanthus, Thasos, Lampsakos, Erythrai, Chios,Samos, Knidos, Lycia, Aspendos, Side, Kelenderis, Soloi, Tarsos, Mallos, Paphos, Kition, and Cypriote Salamis; and

✴[more than 30] from Athens ....

There were a mere handful of Achaemenid coins, and some further primitive stamped currency bars of Indian type, together with some peculiar pieces with rudimentary designs [that were]also Indian in complexion. The hoard is datable (buried ca. 380 BC) ...”

The author of the webpage noted that Schlumberger’s list of 115 coins from the Kabul Museum included:

✴64 Greek coins, all apparently from the 5th and 4th centuries BC (32 from Athens and 30 from other Greek cities);

✴a later Persian imitation of an Athenian ‘owl’ tetradrachm;

✴9 royal Achaemenid silver coins (siglos); and

✴29 locally minted coins; [and]

✴14 ‘punch-marked’ coins in the shape of bent bars;

and that:

“The deposit of the hoard is dated to ca. 380 BC, as this is the probable date of the least ancient datable coin found in the hoard (the [Persian] imitation of the Athenian owl tetradrachm).”

It seems that the the ‘Alexander octadrachms’ recorded by Raymond (above) were not, in fact, recorded in Schlumberger’s paper, presumably because (as she noted) they were already in private collections in 1953. Kenneth Jenkins (as above) observed that the hoard is of particular importance for:

“... the light it throws on the circulation of Greek coins and on the relations between Greeks and the Persian Empire; for the remarkable predominance of Greek coins in this hoard is, as Schlumberger is able to show from comparative evidence, actually far from being an exceptional or isolated phenomenon. Indeed, on the evidence of coin-finds from the area of the Achaemenid empire, Greek coins appear to have played a far larger part in the economy of that empire than did the Persian currency. This is clearly a fact of great importance, and fully deserves the emphasis which M. Schlumberger has given it.”

Acanthus

‘Signed’ tetradrachm (17.20 gm.) of Acanthus from the Kabul Hoard (Desneux 97)

Obverse: Lion attacking a bull (the civic symbol of Acanthus), symbol of a fish below

Reverse: AKANΘION (of Acanthus), inscription surrounding a quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image from Wikipedia

As we have seen, Schlumberger’s list of the coins from the Kabul Hoard that were subsequently housed in the Kabul Museum included two tetradrachms from the city of Acanthus (in northern Greece - see the map below). Jules Desneux (referenced below) published these coins as:

•his coin 45, catalogued at pp.71-2 and illustrated on Plate IX, which had an anepigraphic quadripartite incuse square reverse; and

•his coin 97 (illustrated above), catalogued at p. 85.

Interestingly, in these entries, Desneux cited private communications from Schlumberger as the source of his information).

As we shall see, the second of these coins is important for the analysis that follows, because its reverse design is very similar to that of the ‘Alexander octadrachm’ from this hoard that Raymond catalogued as her coin 52, which suggests that both coins found their way to Afghanistan at about the same time and for a similar reason (albeit that the only other fact that we learn from the evidence of this hoard is that both coins were part of a hoard that was buried there in ca. 380 BC.)

We know of at least five Thracian tribes that minted ‘heavy’ silver coins:

✴two that minted ‘octadrachms’ also appear in our surviving ‘narrative’ sources:

•the Bisaltae (mentioned above); and

•the Edones, who were documented near Maount Pangaeus in the 5th century BC; and

✴three that are known only from the inscriptions on their coins:

•the Derrones (whose heavy coins were minted at various weights, mostly in the range 30-40 gm.); and

•the Orrescii and the Tynenoi, both of which minted ‘octadrachms’.

Two kings (other than Alexander) who issued ‘octadrachms’ of the Thraco-Macedonian types are also known only from their coins:

✴Getas, who identified himself on his coins as basileus (king) of the Edones; and

✴Mosses, who (as we shall see) was probably a king of the Bisaltae, and whose rare coinage includes only a single known ‘octadrachm’.

If we now look at the iconography of the obverses of these ‘octadrachms’:

✴the ‘standing horseman’ obverse was used on coins ‘signed’ by the Bisaltae, Mosses (probably the king of the Bisaltae) and Alexander, as well as on a number of anepigraphic types; and

✴a similar iconography in which a man was depicted between a pair of oxen was used on coins of the the Ichnae, the Tyntenoi, the Orreschi and Getas, king of the Edones.

As Martin Price (referenced below, at p. 44) observed, large coins like these were almost certainly reserved for trade and, in particular, for international trade. The ‘fascinating’ things about them (apart from their unusual size) can be summarised as follows:

✴they were minted by so many different authorities across the region;

✴they had extraordinarily flamboyant obverse designs (in sharp contrast to the conservative obverses of the contemporary civic coinage of northern Greece - see below);

✴they shared some iconographical features , indicative of interaction, if not collaboration, between the issuers;

✴an unexpectedly large number of them found their way into discrete coin hoards in regions outside Thrace and Macedonia; and

✴they were minted for only a relatively short time (perhaps about 25 years) before the practice ended in ca. 450 BC.

Read more:

Wartenberg U., “Thracian Identity and Coinage in the Archaic and Classical Period”, in

Peter U. and Stolba V. F. (editors), “Thrace: Local Coinage and Regional Identity”, (2021) Berlin, at pp. 45-64

Kallet L. and Kroll J. H., “The Athenian Empire: Using Coins as Sources”, (2020) Cambridge

King C., “Ancient Macedonia”, (2018) London and New York

Wiesehöfer J., “The Persian Impact on Macedonia: Three Case Studies”, in:

Müller S. et al. (editors), “History of the Argeads: New Perspectives”, (2017) Wiesbadenm at pp. 57-64

Wartenberg U. and Amandry M. (editors), “ΚΑΙΡΟΣ: Contributions to Numismatics in Honor of Basil Demetriadi” (2015) New York contains;

•Psoma S. E., “Did the So-Called Thraco-Macedonian Standard Exist?”, at pp. 167-90; and

•Wartenberg U., “Thraco-Macedonian Bullion Coinage in the Fith Century BC: the Case of Ichnae”, at pp. 347-64

Tzamalis A. R., “Les Ethné de la Région ‘Thraco-Macédonienne’: Etude d’Histoire et de Numismatique (fin du VIe - Ve siècle)”, (2012) thesis of the University of Paris (Sorbonne)

Sprawski S., “Early Temenid Kings to Alexander I”, in:

Roisman J. and Worthington I. (editors), “A Companion to Ancient Macedonia”, (2010) Malden, MA and Oxford, at pp. 126-44

Delev P., “The Edonians”, Thracia, 17 (2007) 85-106

Strassler R. B., “The Landmark Thucydides : a Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War”, (1996) New York

Price M. J., “The Coinages of the Northern Aegean”, in:

Carradice I. (editor), “Coinage and Administration in the Athenian and Persian Empires: Ninth Oxford Symposium on Coinage and Monetary History”, (1987) Oxford,at pp. 43-7

Kraay C. M. and Moorey P. R. S, “A Black Sea Hoard of the Late Fifth Century BC”, Numismatic Chronicle, 141 (1981) 1-19

Hammond N. G. L. and Griffith G. T., “A History of Macedonia: Vol. II (550-336 BC)”, (1979) Oxford

Starr C. G., “Athenian Coinage, 480-449 BC”, (1970) Oxford

May J.M.F., “The Coinage of Abdera”, (1966) London

Starr C. G,, “The Awakening of the Greek Historical Spirit and Early Greek Coinage”, Numismatic Chronicle (7th Series), 6 (1956) 1-7

Kraay C., “The Archaic Owls of Athens: Classification and Chronology”, Numismatic Chronicle (6th Series), 16 (1956) 43-68

Jenkins G. K., Review of Curiel R. and Schlumberger D. (see below, 1953), Journal of Hellenic Studies, 75 (1955) 184-5

Raymond D., “Macedonian Regal Coinage to 413 BC", (1953) New York

Schlumberger, D., “L’Argent Grec dans l’Empire Achéménide”, in:

Curiel R. and Schlumberger D. (editors), “Tresors Monetaires d'Afghanistan (Memoires de la

Delegation Archeologique Francaise en Afghanistan)”, XIV (1953) Paris, at pp. 5-64

Desneux J., “Les Tétradrachmes d'Akanthos”, (1949) Brussels

Head B. V., “Historia Numorum: A Manual of Greek Numismatics”, (1911, 2nd edition) Oxford

Head B. V., “British Museum Catalogue of Greek Coins, Macedonia, etc”, (1879) London