Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Alexander I: Alexander’s ‘Signed Octadrachms’ II

Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Alexander I: Alexander’s ‘Signed Octadrachms’ II

Asyut Hoard (IGCH 1644; 1968/9)

The first serious challenge to Raymond’s chronology came in 1968/9, when this hoard was discovered on the west bank of the Nile, some 300 km south of Cairo. Martin Price and Nancy Waggoner published it in 1975 (in a book, referenced below, that I have not been able to consult). In his review of this book, Colin Kraay (referenced below, at p. 189) observed that:

“... because of its size (nearly 900 coins) and the variety of its contents, [this hoard] prompts a thorough reassessment of our entire conception of archaic Greek coinage. Despite the hazards of chance discovery and dispersal, it proves to be not only the largest hoard of the period hitherto known, but [also], thanks to [work of Price and Waggoner], by far the most completely recorded. Its contents, [covered] the whole Greek world, including Sicily and south Italy ...” .

Kraay (as above) also noted that Price and Waggoner had listed the coins in the hoard:

“... with professional skill, and ... compared [this list] with those of other archaic hoards in order to determine the date of burial and the relative position of Asyut in the sequence of archaic Greek hoards. [They concluded] that the hoard came late in the sequence, and that its terminal date was ca. 475 BC.”

Alexander I

Silver ‘octadrachm’ (ANS 1970 225 1, 27. 51 gm., clipped) from the Asyut Hoard (coin 152)

Obverse: horseman wearing chlamys and petasus, carrying two spears and standing behind his horse:

waning moon behind his head

Reverse: ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟ: Inscription surrounding quadripartite square within an incuse square

This hoard contained a ‘signed standing horseman octadrachm’ of Alexander (Asyut 152, ANS 1970 225 1, illustrated above). Colin Kraay (referenced below, at p. 190) observed that its presence in the hoard:

“... caused [Price and Waggoner] great embarrassment ... [because it] can only be accommodated before 475 BC (the postulated terminal date of the hoard) by the ruthless reversal of the sequence of Raymond's Groups I and II.”

The problem was that, as we have seen, Price and Waggoner had judged that the hoard had closed in ca. 475 BC; but

✴as we have seen, John May (referenced below, at p. 86, note 2), who accepted May’s assumption that Alexander’ ‘signed’ coinage had started in ca. 480, had argued that the ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ of Raymond’s Group II, which (on her dating) began in ca. 476/5 BC, had probably inspired the introduction of this ‘new reverse’ at both Acanthus and Abdera; and

✴Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 101) had already catalogued four of Alexander’s ‘signed standing horseman, waning moon octadrachms’ (numbered 53-7) as the last coins of her Group II, suggesting that coins of this late type dated to ca. 460 BC.

In order to understand why the closing date of the hoard could not simply be re-assigned to ca. 460 BC, we need to look at the other coins from this region that had been found in the hoard.

Other Coins from Northern Greece in the Asyut Hoard

Derrones

‘Signed’ heavy silver coin (41.06 gm.) of the Derrones,

catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, as coin 22, at p. 41

Obverse: ΔΕΡ[PO] bearded man in armour, wearing a Corinthian helmet and holding a shield,

standing behind two oxen harnessed to a cart

Reverse: quadripartite incuse square

Image from Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, Plate 2)

This hoard contained 14 heavy coins of various weights (ca. 30-40 gm.) ‘signed’ by the Derrones, all of which Alexandros Tzamalis included in his ‘Emission I’. He divided these coins into two groups:

his Group A (coins 1, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 11, catalogued at pp.31-6) have obverses depicting an ox or a pair of oxen harnessed to a cart, the wheel of which is the only visible element: and

his Group B (coins 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 and 22, catalogued at pp. 36-41), which have similar obverses, except that a man now stands behind the ox/ oxen.

Tzamalis noted (at p 337) that these 14 coins coins represent a large proportion (61 %) of the 23 known coins of his ‘Emission I, all of which have anepigraphic quadripartite incuse square reverses. The last of them (illustrated above) is the penultimate coin in Tzamalis’ catalogue before the introduction of the ‘triskeles’ reverse.

Ichnae

‘Signed octadrachm’ (12.83 gm., clipped) of the Ichnae, from the Asyut Hoard

Catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below) as coin 1, p. 176, described below

Image from Tzamalis’ Plate 41

This hoard contained 5 ‘signed octadrachms’ of the Ichnae (Asyut 40-44) which:

Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015) catalogued as coins 2 and 4-7 (at p. 349); and

Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below) catalogued as coins 1-4 and 6 (at pp. 176-8).

These coins all had the same iconography::

their obverses are ‘signed’ ΙΧΝΑΙΩΝ and depict a man wearing a petasus and standing between and controlling two oxen; and

their reverses depict a four-spoked wheel in an incuse square;

as in the ‘TVN’ coin in the Jordanian Hoard, discussed above. Tzamalis noted (at p 337) that these 5 coins represented a large proportion (62 %) of the 8 known coins of his type. Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 352) observed that these five coins:

“... are from four obverse and four reverse dies, and all dies are done by the same hand; they show some wear, which supports the date of 490–480 BC given by Price and Waggoner [(referenced below)]”.

Acanthus and Abdera

This hoard contained:

37 ‘tetradrachms’ from Acanthus; and

10 ‘octadrachms’ and 2 ‘tetradrachms’ from Abdera.

Colin Kraay observed (at p. 192) observed that, if we put Alexander’s coin (see below) to one side:

“... as far as north Greece is concerned, the Asyut Hoard closed while the [anepigraphic] quadripartite incuse square was still the normal reverse type at most mints:

among the Derrones (above);

on the staters of the Orrescii (above); [and]

at Abdera and at Acanthus.”

Although I have been unable to consult the catalogue of Price and Waggoner, I have found two later references that allow us to date these coins of Abdera and Acanthus more precisely (at least in relative terms):

✴Colin Kraay and Peter Moorey (referenced below, 1981, at p. 3) observed that the latest ‘tetradrachm’ from Acanthus in the Asyut Hoard pre-dated Desneaux’ coin 49, which was issued in his Period I (coin types 1-92, ca. 530 - 480 BC); and

✴Martin Price (in Ian Carradice (editor), referenced below, at pp. 45) observed that the latest Abderite coins in the Asyut Hoard belonged to John May’s Period II (520/15 - 492 BC).

Alexander’s ‘Octadrachm and the Asyut Hoard: Conclusions

As Colin Kraay (referenced below, at p. 192) observed:

“As far as north Greece is concerned, the Asyut Hoard closed with the plain quadripartite incuse square was still the normal reverse type at most mints: among the Derrones, on the staters of the Orrreschi, at Abdera and at Acanthus.”

As we have seen::

the latest Abderite coin in the Asyut Hoard belonged to John May’s Period II (520/15 - 492 BC); while

the ‘new’ inscribed reverse had appeared at the time of Phittalos, at the start of May’s period IV, which he dated to 473/70 BC.

Colin Kraay (referenced below, at p. 192) argued that this development in reverse design cannot have occurred in:

“... less than decade, which will bring Alexander's ‘octadrachm no. 152 down the about 465-460, which is about where Raymond originally dated it.”

He therefore argued (at pp. 192-3) that Raymond’s date for Alexander’s ‘waning moon octadrachms’ should stand, and that, although the great majority of the coins in the hoard had probably arrived at Asyut before ca. 475 BC, a reduced flow could have continued for some time before the hoard was actually buried. By way of precedent, he observed that:

“Such a pattern has already been suggested by the Jordan Hoard [above], which was certainly not finally closed until after 450 BC, but which nevertheless contained rather few coins from mainland Greece that could be attributed to the [three decades prior to its closure].”

It seems that Martin Price subsequently accepted Kraay’s analysis: he acknowledged (in Ian Carradice (editor), referenced below, at p. 45) that:

“... as Dr. Kraay has shown, we must accept that the single [coin] of Alexander in the [Asyut] Hoard was an addition to the original deposit.”

The important point for our purposes is that John May (in 1966) and Colin Kraay (in 1977) had demonstrated the importance of the ‘new’ reverse that was introduced at most of the mints of northern Greece at about the same time (ca. 465 BC) in establishing the chronology of the coinage of this region.

Black Sea Hoard (CH 1:115, before 1970)

Colin Kraay and Peter Moorey (referenced below, 1981) published this hoard on the basis of a private coin collection that had been acquired for the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford in 1970. They deduced (at pp. 16-9) that the original hoard on the periphery of the Black Sea or the interior of Asia Minor must have been buried in ca. 420 BC. (Note that Jonathan Kagan presented a paper entitled “Redating the Jordan Hoard, the Syrian [Massyaf] Hoard and the Black Sea Hoard (IGCH 1482, 1483 and CH 1:115) with the Help of Lycian Coins” at the conference “New Hoard Evidence for the Chronology of the 5th century BC Athenian Coinage: 6th December 2022”) which is awaiting publication. }

Bisaltae

Left: fragment of a ‘standing horseman octadrachm’ (12.90 gm.) attributed to the Bisaltae from the Black Sea Hoard,

now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Reverse: inscription completed as [ΒΙΣΑ]ΛΤΙΚ[ΟN], surounding a quadripart itesquare within an incuse square

Image adapted from Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, Photo 2, at p. 382)

Right: adapted from Colin Kraay and Peter Moorey (referenced below, 1981, p. 3, Figure 1)

Letters that I have picked out in red = surviving inscription, as read by Kraay and Moorey;

letters left in black = their completion of the inscription

This hoard contained no coins of Alexander. However, it did contain a fragmentary coin (illustrated above, catalogued by Kraay and Mooray as coin 2, at p. 2) that seems to have been part of a ‘signed standing horseman octadrachm’. This would have been unremarkable, were it not for the fact that, if Kraay and Moorey correctly completed the fragmentary inscription ‘ΛΤΙΚ’ as [ΒΙΣΑ]ΛΤΙΚ[ΟN] (of the Bisaltae), then this was (and still is) the only known Bisaltian ‘signed octadrachm’ on which the ‘signature’ is on the reverse. Furthermore, as Kraay and Moorey observed, its reverse:

“... with its large, regular letters carefully spaced in relation to the axes of the incuse square, is close to the second group of ‘octadrachms’ of Alexander ... , which Raymond dates to 476/5-460 BC.”

Kraay and Moorey acknowledged (at p. 2) that a Bisaltian ‘octadrachm’ with the identifying legend on the reverse represented a new variety, but they justified their completion of the inscription by noting that this coin:

“... matches every detail certain rare octobols, of which only three examples appear to be known.”

Octobols of the Bisaltae

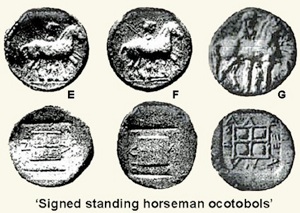

‘Signed octobols’ of the Bisaltae, catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, as coins 1-3, p. 114)

Coin 1: 4.10 gm.; coin 2: 4.06 gm.; coin 3: 3.90 gm. (illustrated by Tzamalis at Plate 29)

Obverse: horseman wearing a petasus and a chiton (tunic), depicted in profile standing behind his horse,

holding two spears that point diagonally downwards

Reverse: B I Σ /Α Λ Τ Ι Κ / Ο Ν: inscribed around a quadripartite square , all within an incuse square

As Alexandros Tzamalis(referenced below, at p. 381) pointed out:

✴the depiction of the horseman on the obverses of these coins is very like that on coins of Alexander: for example, he appears to be clothed and his spears are angled sharply downwards; and

✴until the discovery of the fragmentary ‘octadrachm‘ in the Black Sea Hoard, these were the only known Bisaltian ‘signed standing horseman’ obverses on which the horseman was depicted entirely in profile.

Some scholars had therefore been considered them to be fakes (see also, Doris Raymond, referenced below, at p. 115, note 2), and this uncertainty diluted their use in support of the completion of the inscription on the Black Sea ‘octadrachm. Thus, in Tzamalis’ catalogue entry for the Black Sea ‘octadrachm’ (as coin 133, at p. 113), he gave the reverse inscription as ‘[Β Ι Σ Α] Λ Τ Ι Κ [Ο Ν] (?)’. However, he pointed out (at p. 381) that this completion:

“... was reinforced by the recent publication of [a ‘signed standing horseman octadrachm of the otherwise unknown] Mosses, the obverse of which is identical to [that of the Black Sea ‘octadrachm.

‘Signed Standing Horseman Octadrachm’ of Mosses (Image D, below)

Obverses: Standing horseman wearing a petasus, carrying two spears , standing behind his horse

Reverse: ‘signatures’ surrounding a square divided by two crossed lines within an incuse square:

Inscriptions (all on the reverse):

A = ΑΛΕ/ΞΑ/ΝΔ/ΡΟ, catalogued by Doris Raymond, referenced below, as coin 45a (29.01gm.) at p. 100

B = ΑΛΕ/ΞΑ/ΝΔ/ΡΟ, catalogued by Doris Raymond, referenced below, as coin 46a (26.10 gm.) at p. 100

C = [ΒΙΣΑ]ΛΤΙΚ[Ο]Ν); from the Black Sea Hoard, discussed above

D = ΜΟΣΣΕΩ, cataloged in the Corpus Nummorum as CN type 4358, (29.32 gm)

Image adapted from Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, Photo 2, at p. 382)

The only-known ‘octadrachm’ of Mosses appeared on the market in 2009. Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at p. 381) observed that, on the Mosses obverse (D above):

✴the horseman’s spears are strongly tilted down towards the ground; and

✴he is depicted fully in profile, wearing a chiton (tunic), the lower part of which is visible below the horse.

He noted (at pp. 381-2) that this obverse shares some characteristics with types issued by Alexander:

✴on the ‘octadrachm’ of Alexander that Raymond cataloged as coin 45a (coin A above), the spears are strongly tilted down towards the ground, there is no trace of a chiton below the horse; and

✴on the ‘octadrachm’ of Alexander that she cataloged as coin 46a (coin B above) the chiton is visible below and the spears are ob different lengths, but they are pointing away from the ground.

However, all of the these key characteristics of Mosses‘ coin D:

✴are never found together on a known type of Alexander; but

✴as far as they overlap, they are all found on the surviving fragment of coin C.

Obverses: Standing horseman wearing a petasus , carrying two spears , standing behind his horse

Reverse:‘signatures’ surrounding a square divided by two crossed lines within an incuse square:

Inscriptions:

E = ΒΙΣΑΛΤΙΚΟΝ, seen by Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 115, note 14) ‘at Naples’

F = ΜΟΣΣΕΩ, seen by Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 115, note 14) ‘in Brussels’

Coins of type F are also cataloged in the Corpus Nummorum as:

CN type 4241 (3.98 gm.); and CN type 4356 (2 examples, average weight 3.18 gm.)

G = ΑΛΕ/ΞΑ/ΝΔ/ΡΟ, catalogued by Doris Raymond, referenced below, as coin 68b (4.02 gm.) at p. 103

Images from Doris Raymond (referenced below: E and F = ‘a and b’ at bottom of Plate VI; G=68b, Plate VII

Kraay and Moorey acknowledged (at p. 2) that a Bisaltian ‘octadrachm’ with the identifying legend on reverse would represent a new variety, but they justified their completion of the inscription by noting that this coin:

“... matches every detail certain rare octobols, of which only three examples appear to be known.”

They cited Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 115), who observed that the octobols E and F (see above), which she illustrated in her Plate VI:

“... have their obverses from the same die; one reverse has the Bisaltian ethnic, the other has the name of [the otherwise unknown] Mosses.”

She also observed (at note 2) that:

“Bisaltian octobols of this style are rather rare. I have been able to find:

✴the one illustrated [onPlate VI], from Naples;

✴another in Klagenfurt ... ; and

✴a third in Cambridge ... .”

She argued (at p. 123) that the issues of the octobols of the Bisaltae and Mosses roughly coincided with the issue of those of Alexander in her Group II, and that:

“The Bisaltian octobols and those of Mosses probably ceased with those of Alexander, since the need for that denomination had apparently never been very great in the north.”

Some authorities had initially questioned the authenticity of the octobols of the Bisaltae (a possibility that Raymond had discounted in her note 2). This judgement was to some extent vindicated by:

✴the discovery of the Bisaltian ‘octadrachm’ in the Black Sea Hoard (coin B above); and

✴the subsequent emergence of the ‘octadrachm’ of Mosses (coin C above).

Note that Jonathan Kagan presented a paper entitled “Redating the Jordan Hoard, the Syrian [Massyaf ]Hoard and the Black Sea Hoard (IGCH 1482, 1483 and CH 1:115) with the Help of Lycian Coins” at the conference “New Hoard Evidence for the Chronology of the 5th century BC Athenian Coinage: 6th December 2022”) which is awaiting publication.

Acanthus

‘Tetrdrachm’ (17.36 gm.) of Acanthus, Desneux 49, from Numisbids

Obverse: Lion attacking a bull

Reverse: Quadripart incuse square

The fragment from Acanthus discussed below was apparently of a similar type

This hoard contained a fragment of a ‘tetradrachm’ from Acanthus (coin 3, at p.3). Kraay and Moorey commented that:

“The exact obverse die appears not to be included in Desneux, ... [but] closest are [those following his coin 49, an example of which is illustrated above].”

The coin in the hoard would therefore have fallen into Desneaux’s Period I (coin types 1-92, ca. 530 - 480 BC). However, Kraay and Moorey argued that:

“On the evidence of the Asyut Hoard [(above)], from which these issues were absent, the date should be near 470 BC.”

Read more:

Wartenberg U., “Thracian Identity and Coinage in the Archaic and Classical Period”, in

Peter U. and Stolba V. F. (editors), “Thrace: Local Coinage and Regional Identity”, (2021) Berlin, at pp. 45-64

Kallet L. and Kroll J. H., “The Athenian Empire: Using Coins as Sources”, (2020) Cambridge

King C., “Ancient Macedonia”, (2018) London and New York

Wartenberg U. and Amandry M. (editors), “ΚΑΙΡΟΣ: Contributions to Numismatics in Honor of Basil Demetriadi” (2015) New York contains;

•Psoma S. E., “Did the So-Called Thraco-Macedonian Standard Exist?”, at pp. 167-90; and

•Wartenberg U., “Thraco-Macedonian Bullion Coinage in the Fith Century BC: the Case of Ichnae”, at pp. 347-64

Tzamalis A. R., “Les Ethné de la Région ‘Thraco-Macédonienne’: Etude d’Histoire et de Numismatique (fin du VIe - Ve siècle)”, (2012) thesis of the University of Paris (Sorbonne).

Delev P., “The Edonians”, Thracia, 17 (2007) 85-106

Strassler R. B., “The Landmark Thucydides : a Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War”, (1996) New York

Price M. J., “The Coinages of the Northern Aegean”, in:

Carradice I. (editor), “Coinage and Administration in the Athenian and Persian Empires: Ninth Oxford Symposium on Coinage and Monetary History”, (1987) Oxford,at pp. 43-7

Kraay C. M. and Moorey P. R. S, “A Black Sea Hoard of the Late Fifth Century BC”, Numismatic Chronicle, 141 (1981) 1-19

Starr C. G., “Athenian Coinage, 480-449 BC”, (1970) Oxford

May J.M.F., “The Coinage of Abdera”, (1966) London

Starr C. G,, “The Awakening of the Greek Historical Spirit and Early Greek Coinage”, Numismatic Chronicle (7th Series), 6 (1956) 1-7

Kraay C., “The Archaic Owls of Athens: Classification and Chronology”, Numismatic Chronicle (6th Series), 16 (1956) 43-68

Jenkins G. K., Review of Curiel R. and Schlumberger D. (see below, 1953), Journal of Hellenic Studies, 75 (1955) 184-5

Raymond D., “Macedonian Regal Coinage to 413 BC", (1953) New York

Schlumberger, D., “L’Argent Grec dans l’Empire Achéménide”, in:

Curiel R. and Schlumberger D. (editors), “Tresors Monetaires d'Afghanistan (Memoires de la

Delegation Archeologique Francaise en Afghanistan)”, XIV (1953) Paris, at pp. 5-64

Desneux J., “Les Tétradrachmes d'Akanthos”, (1949) Brussels

Head B. V., “Historia Numorum: A Manual of Greek Numismatics”, (1911, 2nd edition) Oxford

Head B. V., “British Museum Catalogue of Greek Coins, Macedonia, etc”, (1879) London