Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Alexander’s Tetradrachms

Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Alexander’s Tetradrachms

In Construction

Foundation Myth of Aegae

It seems that Diodorus Siculus knew of a legend that related to Perdiccas’ foundation of his capital after he had established his kingdom: the relevant part of Diodorus’ original work is lost, but the following fragment of it survives in Eusebius’ ‘Chronicles’:

“Perdiccas, wishing to increase the strength of his kingdom, sent to Delphi to consult the oracle, and the Pythian priestess replied to him:

‘The noble Temenidai wield royal authority over a wealth-producing land: for aegis-bearing Zeus grants it. But, go in haste to Bouteis, rich in flocks, and, when you see gleaming-horned, snow-white goats sunk in sleep on the ground, sacrifice there to the blessed gods and found there the [capital] city of your state”, (‘Library of History’, 7: fr. 16, with the translation of the words of the oracle given here based on that of Miltiades Hatzopoulos, referenced below, at p. 323).

Thucydides continued his account above by noting that Alexander and his forbears:

“... defeated and expelled:

✴the Pierians from Pieria, ... [at which point they] moved to Phagres and other places at the foot of Mount Pangaeus beyond the Strymon ... and

✴the Bottiaeans, who are now neighbours of the Chalcidians”, (‘History of the Peloponnesian War’, 2: 99: 3, translated by Charles Smith, referenced below, at p. 451).

It is possible that Diodorus’ ‘Bouteis’ referred to the territory from which, according to Thucydides, the ‘Bottiaeans’ had been expelled.

Miltiades Hatzopoulos (referenced below, at p. 323) asserted that the myth recorded by Diodorus had originally been written after that recorded by Herodotus. He did not explain why he took this view, but Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 5) had previously advocated it on the basis that Herodotus’ account of Perdiccas’ arrival in Macedonia (above) did not involve an oracle. However, as we have seen, Herodotus seems to have cut short his account at the point at which the three brothers had completed the subjugation of Macedonia. It seems to me to be unlikely that the local foundation myth actually ended there, and it is thus entirely possible that it continued to include, inter alia, an account in which Perdiccas (who was, after all, a Greek from Argos), having founded his kingdom, consulted the oracle at Delphi and then, on her advice, hastened back to ‘Bouteis, rich in flocks’ and established his capital on the spot where he first saw ‘gleaming-horned, snow-white goats sunk in sleep on the ground’.

Matters are complicated by the fact that a later writer, Hyginus (1st century AD), recorded a version of this foundation myth in which Diodorus’ Perdicas was replaced by the equally mythical and allegedly earlier Archelaus (see below). In Hyginus’ version, Archelaus:

“... fled from Thrace to Macedonia, with a goat leading him, in accordance with an oracular response of Apollo,and founded a town called Aegeae from the name of the goat. Alexander the Great is said to [be his descendant]”, (‘Fabulae’, 219, my changed word order).

As Marc Huys (referenced below, at pp. 28-9) observed, Fabula 291:

“... has generally been considered a summary of [Euripides’ ‘Archelaus' - see below], because this Archelaus, legendary king of Macedonia, is only [recorded in this and some of the] other plays of Euripides. Yet, there are no cogent parallels between the text of Hyginus and the preserved fragments of [these plays]. ... The last sentence, according to which Alexander the Great descended from this Archlaus obviously] cannot be Euripidean. In view of [the many uncertainties arising from the fragmentary sources for Euripides’s original work], most reconstructions of the tragedy, which are based on the present Fabula, should be critically assessed.”

In other words, although Hyginus almost certainly took the name of the founder of Macedonia from Euripides’ ‘Archlaus’, we cannot assume either that:

✴he depended only on Euripides; or

✴his ‘Fabula’ 219 is a good summary of the plot of Euripides’ plays.

In short, both Diodorus and Hyginus could have relied (perhaps indirectly) on the same mythical account of the foundation of Aegae: but

✴Perdicas was named as the founder by Diodorus’ immediate source named; while

✴Eurypides’ immediate source (or perhaps by Eurypides himself) gave this role to Archelaus.

Furthermore, there is no reason why the myth of the foundation of Aegae by a ‘Greek’ invader of Macedonia (not necessarily named Perdiccas) already existed in ca. 480 BC, when Herodotus was at work of his ‘Persian Wars’.

Thraco -Macedonian Goat Staters (early 5th century BC)

Example of a Thraco-Macedonian ‘goat stater’ (ANS 1967 152 181, ca. 470 BC)

Obverse: ligature ΔE: long-horned goat kneeling on the ground, with its head reverted

Reverse: Quadripartite incuse square

As it happens, there might be evidence of an early date for this myth in the the long-horned goat depicted on the ‘goat stater’ illustrated above (which is arguably about to sink in sleep on the ground):

✴the reverse type identifies it as Thraco-Macedonian;

✴the ligature ΔE has been traditionally (although probably incorrectly) associated with Aegae; and

✴as we shall see, it belongs to a series of ‘goat staters’ and associated fractions that probably began in ca. 490-85 BC.

In order to take this further, we need to look in more detail at this coin in the context of the series as a whole. The relevant sources include

✴Barclay Head (referenced below, at pp. 37-8, numbers 1-15, who included the precise type illustrated here as no. 1);

✴Doris Raymond (referenced below, who illustrated the stater types (coins 1-8, with Head’s n. 1 = her coin 6) and associated fractions on her Plate 1;

✴the Mantis database of the American Numismatic Society, which contains the stater illustrated above and 34 associated fractions;

✴Catharine Lorber (referenced below), who recently who more recently published a more up-to-date analysis of 49 ‘goat staters’, which she was able to split into nine separate emissions that could be placed in chronological order (see the list at p. 115, in which the ΔE type is her emission 8). Having investigated evidence from coin hoards that contained some of these types, she concluded (at p. 117) that the stater series began in ca. 490-85 BC, and that the last of these coins were probably minted in ca. 470 BC.

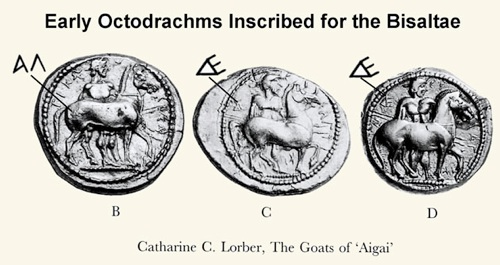

Adapted from Catharine Lorber (referenced below, Plate 14)

Lorber’s list facilitates the further analysis of these related types. Importantly, she identified two emissions that involved types characterised by inscriptions:

✴emission 7, characterised by the letters ΛA (7a), AΛ (7b) or A.Λ (7c), which she dated to 478-5 BC (at p. 127) and identified as issues of Alexander at p. 129:

✴emission 8, characterised (as we have seen) by the ligature ΔE, which she dated to ca. 470 BC (at p. 127).

She also observed (at p. 127, note 50 and in the illustrations above) that:

✴an early octodrachm inscribed for the Bisaltae (east of Macedonia - see the map above) had an obverse type of a horseman wearing chlamys and petasus, carrying two spears and leading horse (discussed below) in which the horse’s rump was ‘branded; with the letters AΛ (coin B above) and probably dated to 478-5 BC; and

✴two others with essentially the same obverse, which she dated to ca. 470 BC, belonged to a type with the ligature ΔE behind the horseman (coins C and D above).

She pointed out that the presence of the ligature ΔE on the these Bisaltian coins undermined the traditional view that it indicated a mint at Aegae. Instead, she identified the king of the Bisaltai (see below) but argued that these coins were not issued not by the Bisalti themselves (since they used their full name on their coins). She suggested therefore that they were issued by the king of another local tribe who:

had acknowledged the king of the Bisaltae as his overlord inca. 470 BC,

having acknowledged Alexander as is overlord in

Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 49 argued that)

“The type is of purely local significance , a ‘canting type’ which may have given rise to the fictitious oracles.”

She referred here to two oracles, which she had discussed at p. 4, note 14:

one associated with the mythical Perdiccas and recorded by Diodorus ( under discussion here); and

another associated with the mythical Caranus (see below); and

acknowledged that these might well represent two versions of the same myth.

(the original of which could well have pre-dated both of them).

She concluded () that:

the types with the letters ΛA and AΛ i;

the ligature ΔE:

Read more:

Hatzopoulos M.,”Federal Makedonia”, in:

Beck H. and Funke P. (editors), “Federalism in Greek Antiquity”, (2015) Cambridge, at pp. 319-40

Lorber C. C., “The Goats of’Aigai’”, in:

Hurter S. and Arnold-Biucchi C. (editors), “Pour Denyse: Divertissements Numismatiques”, (2000) Bern (at pp. 113–33)

Huys M., “Euripides and the ‘Tales from Euripides’: Sources of the Fabulae of Ps.-Hyginus?” Archiv für Papyrusforschung und Verwandte Gebiete, 43:1 (1997) 11-30

Raymond D., “Macedonian Regal Coinage to 413 BC", ANS Numismatic Notes and Monographs, 126 (1953)

Smith C. F. (translator), “Thucydides: History of the Peloponnesian War, Vol. I, Books 1-2”, (1919) Cambridge MA

Head B. V., “British Museum Catalogue of Greek Coins, Macedonia, etc”, (1879) London