Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (3360 - 282 BC)

Diadochi (323 - 282 BC)

Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (3360 - 282 BC)

Diadochi (323 - 282 BC)

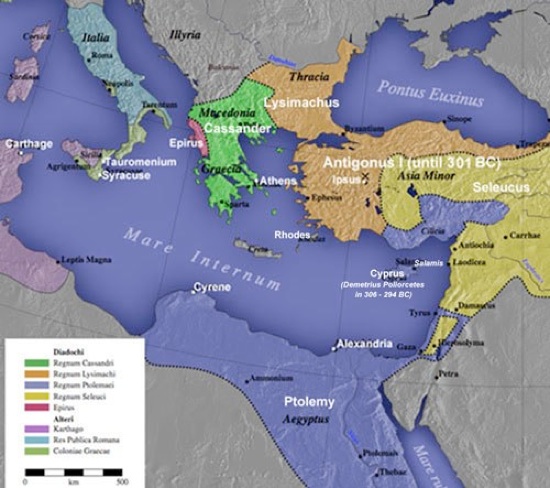

Mediterranean powers after the death of Alexander the Great (adapted from Wikipedia)

Cassander (317 - 307 BC)

Once Cassander was established in Macedonia, Polyperchon retreated to Epirus, where he joined Olympias (the mother of Alexander the Great), who had custody of Alexander IV and his mother, Roxana. Olympias and Polyperchon agreed an alliance with Aeacides, king of Epirus, and invaded Macedonia. They captured Philip III and his wife, Eurydice, at Amphipolis: Philip was executed on 25 December 317 BC, while Eurydice was forced to commit suicide. Aeacides’s soldiers mutinied and he was (temporarily) driven from Epirus. Olympias had established her base at in Pydna. Cassander returned from the Peloponnesus in 316 BC, captured Pydna, executed Olympias, and took Alexander IV and Roxana into his custody. In order to improve his standing with the Macedonians, he married Thessalonike, a daughter of Philip II and half-sister of Alexander the Great.

In 315 BC, Antigonus opened hostilities with Cassander: according to Diodorus Siculus, he assembled at a public assembly at Tyre at which he denied that Cassander was the legitimate regent for Alexander IV and:

“... introduced a decree, according to, which it was voted that Cassander was to be an enemy unless he ...

✴released [Alexander] and his mother, Roxana, from imprisonment and restored them to the Macedonians; and

✴yielded obedience to Antigonus himself, the duly established general, who had succeeded to the guardianship of the throne.

It was also stated that all the Greeks were free, not subject to foreign garrisons, and autonomous”, (‘Library of History’, 19: 61: 3).

Antigonus clearly intended to remove Cassander and, to further this end, he made peace with Polyperchon and sent troops to his aid. Cassander duly formed an alliance with Ptolemy, Seleucus (satrap of Babylon) and Lysimachus in opposing Antigonus, and thus began the so-called Third Diadochi War (315 - 311).

Outcome of the Third Diadochi War (315 - 311), from this page in Wikipedia

Shane Wallace (referenced below, at pp. 56-8) described the military gains that that Antigonus made after the outbreak of war, and concluded (at p. 59) that:

“By 311 BC, Antigonus‘ position within Asia Minor, the Aegean, the Peloponnese, and central Greece was secure.”

However, he noted that he had also suffered losses: for example, Ptolemy and Seleucus had inflicted a humiliating defeat on his son, Demetrius at the Battle of Gaza in late 312 BC, and Ptolemy had subsequently taken Sidon and Tyre. Furthermore, as John McTavish (referenced below, at p. 69) observed:

“ ... in the spring of 311 BC, [Seleucus, who was then in Babylon] had declared himself the strategos autokrator of Asia: by this action, Seleucus attempted to usurp Antigonus’ power, and thereby decisively challenged him ... as the rightful supreme military representative of [Alexander IV in Asia].

Thus, according to Diodorus Siculus:

“... Cassander, Ptolemy and Lysimachus came to terms with Antigonus and made a treaty, in which it was provided that:

✴Cassander should serve as general of Europe until [Alexander IV], the son of Roxana, should come of age;

✴Lysimachus should rule Thrace;

✴Ptolemy should rule Egypt and the adjacent cities in Libya and Arabia;

✴Antigonus should have first place in all Asia [Minor]; and

✴the Greeks should be autonomous”, (‘Library of History’, 19: 105: 1).

As John McTavish (referenced below, at p. 72) pointed out:

“ It is notable that Seleucus was excluded from the peace settlement of 311/310 BC, and that Seleucus’ usurpation of the title ‘strategos of Asia’ was not formally accepted by Ptolemy, Lysimachus, or Cassander, who all agreed to recognise Antigonus as the legitimate strategos autokrator of Asia.”

(Although Antigonus continued to contest Seleucus’ position in the east, he was ultimately unsuccessful.)

The cynicism of Antigonus’ earlier concern for the legal rights of Alexander IV was laid bear in 310 BC, when Cassander ordered the murder of both Alexander and Roxana and neither he nor any of the one of the other Diadochi complained. The Macedonian throne was now left vacant, presumably as a mark of respect for the now-defunct Argead dynasty. Macedonia was nevertheless firmly in Cassander’s hands and, although Antigonus had extended his patronage of the Greeks over a wide swathe of territory, Casssander still had his garrison and his governor at Athens.

The peace between the Diadochi continued until 307 BC, when Antigonus revived his declaration in favour of ‘freedom for the Greeks’ and dispatched a fleet to Athens, under the command of his son, Demetrius Poliorcetes: as we shall see, Demetrius received this epithet (which means besieger) a few years later, but I will use it here to distinguish him from Demetrius of Phalerum. According to the gushing Plutarch:

“This was the most noble or just war waged by any of the [soon-to-be Hellenistic] kings; for the vast wealth that they had amassed by subduing the Barbarians was now lavishly spent to win glory and honour for the Greeks. ... Antigonus would not hear of [any suggestion that he should capture Athens]; he said that the goodwill of a people was a noble gangway that no waves could shake, and that Athens, the beacon-tower of the whole world, would speedily flash the glory of their deeds to all mankind. So, [Poliorcetes] sailed, with 5,000 talents of money and a fleet of 250 ships, against Athens, where Demetrius the Phalerean was administering the affairs of the city for Cassander and commanding the garrison at Munychia. By virtue of forethought combined with good fortune, [when] he appeared off Piraeus [with a few of his ships], ... everybody thought that the ships belonged to Ptolemy and prepared to receive them. ... [Thus, Poliorcetes] was soon inside the harbour and in view of all. He then signalled from his ship a demand for quiet and silence. When this was secured, his herald ... proclaimed that he had been sent by his father ... ;

✴to set Athens free;

✴to expel [the Macedonian] garrison; and

✴to restore to the people their laws and their ancient form of government (‘Life of Demetrius’, 8: 1-5)

It seems that this piece of theatre had the desired effect:

“On hearing this proclamation, most of the people at once threw down their shields ... and urged [Poliorcetes] to land, hailing him as their saviour and benefactor. [Even the party that had previously supported Demetrius of Phalerum was won over. Demetrius himself], owing to the change of government, was more afraid of his fellow-citizens than of [Poliorcetes], .... who, out of regard for his good reputation and excellence, sent him and his friends under safe conduct to Thebes, as he desired”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 9: 1-2).

Demetrius Poliorcetes in Greece (307 - 304 BC)

At this point, the relationship between Demetrius and Athens was ambiguous. According to Diodorus Siculus, Demetrius had:

“... restored to the [Athenians] their freedom and established friendship and an alliance with them. ... Thus the common people, who had been deprived of power ... by Antipater 15 years before [and then by Cassander], unexpectedly recovered the constitution of their fathers. ... When an Athenian embassy [subsequently] came to Antigonus and delivered to him the decree concerning the honours [that the Athenians had] conferred upon him ... , he gave them 150,000 medimni of grain and timber sufficient for 100 ships. He also withdrew his garrison from Imbros and gave that city back to the Athenians”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 46: 1-5).

Thus, Diodorus portrayed Antigonus and Demetrius as the liberators of the grateful Athenians. Shane Wallace (referenced below, at p.63) added that:

“Importantly, [Demetrius’] removal of the garrison in Munychia ensured the perpetuation of the restored democracy. ... Piraeus and the garrison in Munychia were the cornerstones of Athenian freedom and democracy, and Demetrios understood as much.”

However, as Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn (referenced below, at p. 128) pointed out, in some respects, this ‘freedom’ was illusory:

“With an armada of 250 ships [offshore] and a huge army bivouacked in the city, the Athenians were certainly in no position to gainsay Demetrius on any matter. ...

✴[Cassander had at least returned to Macedonia in 317 BC, albeit while leaving a governor and a garrison behind.

✴Now], Demetrius commenced the process of transforming Athens itself into his own, personal residence ...”.

Demetrius spent the winter of 307/6 BC at Athens, and it was probably during this stay that he:

✴took a second wife, Eurydice (a prominent Athenian lady who was the widow of Ophellas, a previous governor of Cyrene - see below); and

✴began negotiations with the other Greek cities that remained under Cassander’s hegemony.

However, as we shall see, he did not spend much time in Athens , which was now governed was effectively governed by two of the leading ‘democrats’ in the city, Demochares and Stratocles.

Fourth Diadochi War (306 - 301 BC)

The Antigonid ‘liberation’ of Athens from Cassander’s hegemony is conventionally characterised as the opening event in the so-called Fourth Diadochi War (307 - 301 BC). However, hostilities began in early 306 BC, when Antigonus summoned Demetrius into the eastern Mediterranean with orders to seize Cyprus from Ptolemy. Demetrius defeated Ptolemy’s fleet in a great naval engagement off Salamis, which Pat Wheatley (referenced below, 2001, at p. 133) characterised as:

“One of the crucial turning points in the continual ebb and flow of power that characterises the decades following the death of Alexander the Great ...”

As she pointed out (at p. 151), this victory:

“... altered the balance between the [Diadochi]:

✴Ptolemy was shattered, but able to hold satrapy against an ill-judged Antigonid invasion attempt in November the same year;

✴Seleucus was preoccupied in the far east; and

✴Cassander's stranglehold in Greece had been broken.

The Antigonids had consolidated their realm in Asia Minor and the Levant, and Demetrius now held an unassailable [maritime empire] from Palestine to the Hellespont. The only semi-independent [maritime centre between these two points] was Rhodes and, within a year, this island too would face the might of new superpower.”

(Demetrius acquired his epithet Poliorcetes (besieger of cities) for his ultimately unsuccessful siege of this formidable stronghold in 305-4 BC).

According to Plutarch, after the victory at Salamis, Demetrius:

“... bestowed on the Athenians 1, 200 suits of armour from the spoils”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 17:1).

When the news of the victory reached Antigonus at his new capital, Antigoneia (in what is now northern Syria):

“... the multitude [there] saluted Antigonus and Demetrius as basileis (kings) for the first time. ...”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 18: 1).

Pat Wheatley (referenced below, 2001, at p. 156) observed that this episode

“... was not an instance of one man usurping the [royal] title: with the elevation of Demetrius to the royal office in association with his father, a royal family and a future dynasty was established.”

The Argead dynasty had died out in 310 BC, was thus replaced in 306 BC by that of the Antigonids, with Antigoneia as their capital. The other Diadochi could hardly have failed to respond to this audacity: according to Diodorus Siculus, after the Antigonids’ victory at Salamis:

“Ptolemy, not at all humbled in spirit by his defeat, also assumed the diadem and always signed himself king. And ... in rivalry with [Antigonus, Demetrius and Ptolemy], the [other Diadochi] also called themselves kings:

✴Seleucus, who had recently gained the upper satrapies; and

✴Lysimachus and Cassander, who still retained the territories originally allotted to them [under the peace of 311 BC]

When Agathocles, [the tyrant of Syracuse, who controlled Greek Sicily - see below] heard that the princes whom we have just mentioned had assumed the diadem, he also called himself king, since he thought that he was not inferior to them in power, territory and achievements”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 53:3 - 54:1 4).

Erich Gruen (referenced below), argued that

✴Ptolemy probably adopted his regal title in the period January-July 304 BC, by which time Antigonus was under pressure on all fronts (see at pp. 113-4);

✴Seleucus probably did so at about the same time (since his first regal year began in March 305 BC in the babylonian king list, and he was recognised as such in the dating of a document on 16th April 304 BC), followed shortly by Lysimachus (see p. 114); and

✴Cassander probably waited rather longer, perhaps wary of Macedonian sensitivities and of his precarious hold over his remaining Greek subjects (see p. 113).

I return to the case of Cassander below: for the moment, we should note that, in 304 BC, Demetrius had to abandon the siege of Rhodes when:

“...the Athenians called [him] back because Cassander was besieging their city”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 23: 1).

Athens under Demetrius Poliorcetes: II (304 -1 BC)

Demetrius Poliorcetes’ stay in Athens (304-2 BC)

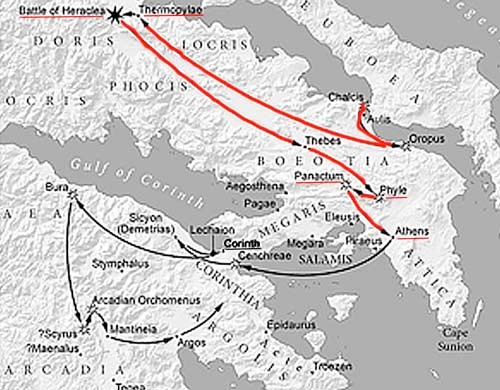

Probable march of 304 BC (from Chalcis to Athens) in red

Adapted from Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn (referenced below, Map 5, at p. 215)

According to Plutarch, on receiving the news from Athens, Demetrius left Rhodes with 330 ships and (probably having landed at Aulus):

“... drove Cassander out of Attica and pursued him ... as far as Thermopylae. He then took Heracleia, which joined him of its own accord, and 6,000 Macedonians also came over to him. On his return [to Athens], he gave freedom to the Greeks on this side of Thermopylae, made the Boeotians his allies and captured Cenchreae[near Corinth]; he also reduced Phyle and Panactum (fortresses of Attica in which Cassander had garrisons) and gave them back to the Athenians”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 23:1 - 24:1).

With the threat from Cassander eliminated, Demetrius spent a second winter in Athens. According to Plutarch, as he became evermore dissolute and autocratic, the cowed Athenians voted that:

“... whatsoever King Demetrius should ordain in future should be held righteous towards the gods and just towards men. And, when one of the better class of citizens declared that Stratocles was mad to introduce such a motion, Demochares ... observed that:

‘He would have been mad not to be mad.’

For Stratocles reaped much advantage from his flatteries, while Demochares, [who had spoken his mind], was ... sent into exile. Thus, the Athenians [learned that, although] they were rid of their [Macedonian] garrison, this did not mean that they had gained their freedom”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 24: 4-5).

Stratocles was now in the most powerful citizen at Athens.

In early 303 BC, Demetrius embarked on another campaign against Cassander that brought him control of Corinth and the northern Peloponnese. As Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn (referenced below, at p. 216) observed:

“... Corinth was to become the strategic cornerstone and jewel of the Antigonid dominions and passed into a 70 year period under their control.”

Pat Wheatley (referenced below, 2020, at p. 59) argued that it was at this point that Demetrius:

“... attempted to legitimise his hegemony over the Greek cities through a powerful cultural initiative ... .”

She described (at p. 64) the ‘calendrical’ alchemy’ that Stratocles employed so that, by the time that Demetrius returned to Athens in May 303 BC,a ritual that normally took 19 months had been performed in around two weeks, and argued (at p. 69) that this Eleusinian initiation was an important precursor to Demetrius’ participation in the following pan-Hellenic events recorded by Plutarch:

“At Argos, ... where there was a celebration of the festival of Hera, [the newly initiated Demetrius] presided at the games and attended the solemn assemblies with the Greeks, and married [his third wife], Deidameia, [see below] ... And, at the Isthmian Games of Corinth, where a general assembly [of the Greeks] was held and throngs of people came together, he was proclaimed commander-in‑chief of the Greeks, as Philip and Alexander had been proclaimed before him ...”

Thus King Demitrius was now the hegemon of a re-formed Corinthian League of Greek states, the original league having been dissolved after Alexander’s death. Antigonus refused the offer of peace. He was now confident that he was on the brink of a total victory. Demetrius was to advance on Macedonia from the south, while he attacked from the east, and Cassander would be crushed between the two armies.

According to Cn. Pompeius Trogus (ca. 10 AD), as epitomised by M. Junianus Justinus (3rd century AD), relations between the Hellenistic kings rapidly deteriorated at about this time, because:

“Ptolemy, Cassander and the other leaders of their faction [i.e. Seleucus and Lysimachus], perceiving that they were individually weakened by Antigonus, ... prepared [to attack him in concert]. Cassander, being unable to take part because of a war near home, despatched Lysimachus to the support of his allies with a large force”, (‘Epitome of Pompeius Trogus’, 15: 3: 15).

Thus, in 302 BC:

✴Demetrius, as commander-in‑chief of his Corinthian League of Greek states (including Athens) , threatened Cassander; but

✴Antigonus was threatened on three sides by a military alliance of Ptolemy, Seleucus and Lysimachus.

Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn (referenced below, at p. 229) characterised the formation of this alliance as:

“A brilliant strategy, most likely masterminded by [the beleaguered] Cassander, developed to destroy the Antigonids.”

In the run-up to the impending engagement to the east, Demetrius marched north towards Macedonia and had reached Thessaly and taken Cassander’s garrison at Pherae when, as Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn (referenced below, at p. 234) noted:

“... messengers from Antigonus arrived, and the course of history altered.”

Erich Gruen (referenced below, at p. 115) argued that Cassander eventually:

“... yielded to temptation [to assume regal status], possibly after shoring up support to confront Demetrius in 303/2 BC. [He] soon designated himself on bronze coinage [see this coin minted at either Amphipolis or Pella in Macedonia] and epigraphic documents as ‘king of the Macedonians’.”

According to Diodorus Siculus:

“While affairs in Thessaly were in this state, messengers sent by Antigonus came to Demetrius, ... bidding him take his army across into Asia as swiftly as possible. ... [He therefore] came to terms with Cassander, making the condition that the agreements should be valid only if they were acceptable to his father; for, although he knew that his father would not accept them, ... [he] wished to make his withdrawal from Greece appear respectable and not like a flight. Indeed, it was written among other conditions in the agreement that the Greek cities were to be free, not only those of Greece but also those of Asia. Then Demetrius ... set sail with his whole fleet and, going through the islands, put in at Ephesus”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 111: 1-3).

As we shall see, ihe was unable to return to Athens until 294 BC.

Battle of Ipsus and its Aftermath (301 - 294 BC)

Demetrius, Cassander, Lysimachus and Antigonus before the Battle of Ipsus (301 BC)

Adapted from the map in this page in Wikipedia

Antigonus and Demetrius now joined forces and engaged with the allied army under Lysimachus at Ipsus. The Antigonid army was defeated and Antigonus himself was killed. According to Plutarch:

“...the victorious kings carved up the entire domain which had been subject to Antigonus and Demetrius, as if it had been a great carcass, and took each his portion, adding thus to the provinces that the victors already had, those of the vanquished kings, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 30: 1).

Lysimachus and Seleucus were the major beneficiaries in terms of territorial gains (see the map at the top of the page).

After this disaster, Demetrius was able to reach his fleet at Ephesus and escape by sea. According to Plutarch, he had placed:

“... his chief remaining hopes in Athens, since he had left ships and his money there, as well as his [third] wife Deidameia, and thought that ... no refuge could be more secure than the goodwill of Athens. However, as he drew near the Cyclades islands, an embassy from Athens met him with a request to keep away from the city, on the grounds that the people had passed a vote to admit none of the kings, and informing him that Deidameia had been sent to Megara with fitting escort and honour”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 30: 2-3).

It seems that there had been a coup at Athens in which Stratocles had been removed from power: according to Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn (referenced below, at p. 301):

✴Stratocles had proposed more than 20 decrees to the Athenian assembly in 307-1 BC (many of which had granted religious and political honours to Antigous and/or Demetirius); and

✴the last of these dated to August/ September 301 BC, after which he is not heard of for some time.”

Cassander recovered his Greek possessions and the Corinthian League was abandoned.

Demetrius established a new base in Greece in the territory of Megara and Corinth. As Carlos Francis Robinson (referenced below, at p. 88) observed, although he had suffered a serious setback, he:

“... still possessed Cyprus and, after recovering his fleet from Athens, maintained possession of areas such as the Corinthian Isthmus and Cilicia, as well as the important ports of Tyre and Sidon.”

Finally, Demetrius had acquired an ally in Pyrrhus, the 17 year old brother of Deidameia: he was the rightful king of Epirus, and had fled to Demetrius after Cassander had arranged for his overthrow, and he had fought with distinction at Ipsus and remained with Demetrius thereafter.

According to Plutarch, Demetrius soon:

“... left Pyrrhus in charge of Greece, while he himself put to sea and sailed to the Chersonesus (in Thrace). Here he ravaged the territory of Lysimachus, thereby enriching and holding together his own forces ... Nor did the other kings try to help Lysimachus”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 31: 2).

At about this time, a serious rift erupted between Seleucus and Ptolemy; according to Cn. Pompeius Trogus (ca. 10 AD), as epitomised by M. Junianus Justinus (3rd century AD):

“... the [previously] allied generals ... turned their arms against each other; and, as they could not agree about the spoil [from the territory taken from Antigonus] ... :

✴Seleucus allied himself with Demetrius; and

✴Ptolemy allied himself with Lysimachus”, (‘Epitome of Pompeius Trogus’, 15: 4: 23-4).

These realignments probably dated to 299/8 BC.

Demetrius’ new alliance soon bought him considerable benefits: according to Plutarch:

“... Seleucus sent and asked the hand in marriage of of Stratonicé, the daughter of Demetrius and [his first wife], Phila. (Seleucus already had a son, Antiochus, by Apama the Persian; but he thought that his realms would suffice for more successors than one, and that he needed this alliance with Demetrius, since he saw that Lysimachus also was taking one of Ptolemy's daughters for himself, and the other for Agathocles his son.) Since a marriage alliance with Seleucus was an unexpected piece of good fortune for to Demetrius, he took his daughter and sailed with his whole fleet to Syria. He was obliged to touch at several places along the coast, and made landings in Cilicia, which country had been allotted by the kings to [Cassander’s brother], Pleistarchus, after their battle with Antigonus, and was now held by him”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 31: 3-4).

Seleucus chose to ignore Pleistarchus’ complaints. According to Plutarch, in ca. 298 BC:

“... Deidameia came by sea from Greece to join Demetrius, and after being with him a short time, succumbed to some disease. Then, by the intervention of Seleucus, friendship was made between Demetrius and Ptolemy, and it was agreed that Demetrius should marry Ptolemaïs the daughter of Ptolemy”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 32: 3).

Plutarch also recorded that:

“... when Demetrius made peace with Ptolemy, [Pyrrhus] sailed to Egypt as hostage for him”, (‘Life of Pyrrhus’, 4: 3).

I will return to Pyrrhus’ subsequent career below.

Demetrius’ Invasion of Athens (295 BC)

According to Plutarch, in ca. 295 BC:

“... learning that Lachares had usurped sovereign power over the Athenians in consequence of their dissensions, Demetrius decided ... to make an easy capture of the city”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 33: 1).

Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn (referenced below, at p. 303) suggested that the unrest at Athens had arisen because of tyrannical behaviour of Lachares, the commander of the foreign mercenaries in the city and had come to a head at some time before July/ August 296 BC, at which point, Demetrius had opportunistically:

“... crossed the sea in safety with a great fleet but ... he encountered a storm [off the coast of Attica] in which most of his ships were lost ... [While he awaited reinforcements], he seized a ship laden with grain for Athens... [and turned back others, causing a serious food shortage in the city]. The Athenian were afforded slight respite by the appearance off Aegina of 150 ships that Ptolemy sent to assist them. [However, when 300 ships arrived to reinforce Demetrius’ fleet], Ptolemy put off to sea in flight and Lachares the tyrant abandoned the city ...”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 33: 1-4).

In early 295 BC, Demetrus entered Athens and reassured its terrified inhabitants when he:

“... gave them 100,000 bushels of grain, and established the magistrates who were most acceptable to the people”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 34: 4).

The relieved Athenians then agreed:

“... that Piraeus and Munychia should be handed over to Demetrius the king, ... and Demetrius, on his own account, also put a garrison into the Museium [a hill near the Acropolis], so that the [Athenians] might not again shake off the yoke and give him further trouble”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 34: 4-5).

According to Plutarch, Demetrius then marched against Sparta, but pulled back when he heard that:

✴Lysimachus had taken some his remaining cities in Asia (including Ephesus and Miletus); and

✴Ptolemy had taken Cyprus and was besieging Salamis, where his mother and children were trapped (although Ptolemy subsequently released them). It is possible that Ptolemy also seized Sidon and Tyre at this time.

Early Career of Pyrrhus of Epirus (ca. 302 - 294 BC)

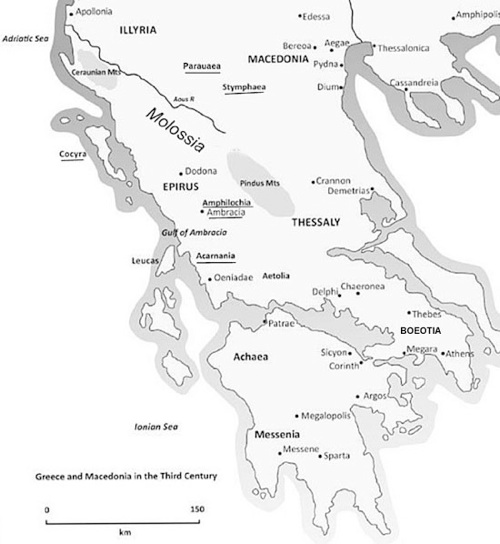

Greece and Macedonia in the 3rd Century BC

Adapted from Jeff Champion (referenced below, Map 1, p. 12)

Although Pyrrhus had a claim to the throne of the Molossians (the only one of the tribes of Epirus that is known to have had a monarchy), he grew up as an exile at the court of Glaucias, king of the Illyrians. In ca. 302 BC, Glaucias entered into an alliance with Antigonus, which was cemented by the marriage of Demetrius (son of Antigonus) and Deidamia, Pyrrhus’ older sister. As we have seen, the young Pyrrhus fought with distinction at Ipsus in 301 BC and remained with Demetrius in Greece thereafter. In ca. 299 BC, when Demetrius sailed to Syria to join his new ally, Seleucus, he left Pyrrhus ‘in charge of Greece’. Deidamia, who initially remained with Pyrrhus, died soon after she joined Demetrius in Syria in 298 BC. Shortly thereafter, Demetrius made peace with King Ptolemy and (as we have seen) demonstrated his good faith by sending Pyrrhus to Alexandria as a hostage.

Return to Epirus (297 BC)

According to Plutarch, Pyrrhus:

“ ... gave Ptolemy proof of his prowess and endurance [and took particular trouble to impress [Ptolemy’s favourite wife], Berenicé ... Since he was orderly and restrained in his ways of living, he was selected from among many young princes as a husband for Antigone, one of the daughters of Berenicé, whom she had had by [the otherwise unknown] Philip before her marriage with Ptolemy”, (‘Life of Pyrrhus’, 4: 3).

Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn (referenced below, at pp. 293-4) reasonably argued that Pyrrhus might well have transferred his allegiance from Demetrius to Ptolemy after the death of Deidameia. In any event in 297 BC:

“After this marriage, [Pyrrhus] was held in still greater esteem and, since Antigone was an excellent wife to him, he brought it to pass that he was sent into Epirus with money and an army to regain his kingdom”, (‘Life of Pyrrhus’, 5: 1).

It seems that Pyrrhus initially agreed to share power in Epirus with the incumbent, Neoptolemus II, whom he murdered shortly thereafter.

Corcyra (295-4 BC)

Pyrrhus soon acquired nominal control of the island of Corcyra (modern Corfu) when he married Lanassa, the daughter of King Agathocles of Syracuse, who brought him the island as part of her dowry.

Diodorus Siculus recorded how Agathocles had acquired Corcyra in ca. 298 BC:

“When Cassander, king of Macedonia, was besieging [the town] on land and sea and was on the point of capturing it, it was saved by Agathocles, king of Sicily, who set fire to the entire Macedonian fleet”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 105: 1).

According to Plutarch::

“In order to enlarge his interests and power, Pyrrhus] married several wives after the death of Antigone [in ca. 295 BC]. He took to wife:

✴a daughter of Autoleon, king of the Paeonians;

✴Bircenna, the daughter of Bardyllis the Illyrian; and

✴Lanassa, the daughter of Agathocles of Syracuse, who brought as her dowry the city of Corcyra [modern Corfu], which had been captured by Agathocles”, (‘Life of Pyrrhus’, 9: 1).

However it was not long before:

“Lanassa, who found fault with Pyrrhus for being more devoted to his barbarian wives than to her, had retired to Corcyra and, since she desired a royal marriage, invited Demetrius [to the island]. So Demetrius sailed thither, married Lanassa, and left a garrison in the city, (‘Life of Pyrrhus’, 10: 5).

Lanassa’s change of heart probably took place shortly after Demetrius became King of Macedonia (see below).

Macedonia (294 BC)

According to Plutarch, after the death of King Cassander of Macedonia in 297 BC:

“... the eldest of [Cassander’s] sons, Philip, reigned over the Macedonians for a only short time before he also died. The two remaining brothers quarrelled with one another over the succession. In 294 BC:

✴one of them, Antipater, murdered his mother, Thessalonicé and

✴the other, Alexander, summoned to his help Pyrrhus from Epirus, and Demetrius from the Peloponnese”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 36: 1).

As we have seen, Demetrius was preoccupied at that point with the Athenians and then the Spartans. Pyrrhus therefore arrived in Macedonia before him and expelled Antipater, who fled to his father-in-law, Lysimachus, in Thrace. According to Plutarch, Pyrrhus then:

“... demanded Stymphaea and Parauaea in Macedonia, ... [as well as] Ambracia, Acarnania, and Amphilochia. The young Alexander gave way to his demands, and Pyrrhus [garrisoned his new possessions]. He then stripped Antipater of the remaining parts of his kingdom and turned them over to Alexander”, (‘Life of Pyrrhus’, 6: 2-3).

The result was that Macedonia was split into two:

✴The new territory that had fallen to Pyrrhus possessions thus became part of the Epirote alliance and, according to Strabo, Ambracia:

“... was adorned ... by Pyrrhus, who made the place his royal residence”, (‘Geography’, 7: 7: 6).

✴Alexander and Antipater were subsequently reconciled at the behest of Lycymachus and shared what remained of Macedonia.

Demetrius, King of Macedonia (294 - 288 BC)

Later in 294 BC, Demetrius marched on Macedonia, ostensibly in response to Alexander’s earlier request for help. However, when Alexander came out to meet him, he murdered him, at which point Antipater fled once more to Lysimachus. According to Plutarch, the Macedonian soldiers who had accompanied Alexander then proclaimed Demetrius king of the Macedonians:

“... owing to:

✴their hatred of [the young] Antipater, who was a matricide; and

✴their lack of a better alternative;

Furthermore, the change was not unwelcome to the Macedonians at home, because they still remembered:

✴the crimes that the hated Cassander had committed against the line of Alexander the Great; and

✴the moderation and justice of [his father], the elder Antipater, which benefitted Demetrius because:

•he was the husband of Phila, Antipater's [much-respected] daughter; and

•they had a son by her, [Antiginos Gonatus], ... who was already ... serving in [Demetrius’] army and who would make a worthy successor”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 37: 2-3).

Thus, Demetrius took at least part of Cassander’s kingdom without bloodshed and assumed the prestigious title of King of Macedonia, albeit that some of what has been Macedonian territory remained in the hands of Pyrrhus.

Jeff Champion (referenced below, at p. 52) observed that:

“With his conquest of Macedonia secure, Demetrius now controlled a strong empire that included the entire Greek peninsula, with the exception of Epirus, Sparta and Messenia.”

He nevertheless faced revolts in Boeotia in 293 and 292 BC, and, on this second occasion, he had to return to Thessaly to fight off an invasion by Pyrrhus and his allies from Aetolia. In 289 BC, Demetrius returned the compliment by invading Aetolia and Epirus. Pyrrhus secured a victory against Demetrius’ general, Pantauchus, at which point Demetrius withdrew to Macedonia. Plutarch gave an elaborate account of Pyrrhus’ performance on this occasion which ended with the claim that:

“This conflict did not fill the Macedonians with wrath and hate towards Pyrrhus, ... but rather led those who witnessed his exploits and engaged him in the battle to esteem him highly ... They likened his appearance and agility to those of the great Alexander, ... They said that, while the other kings represented Alexander with their purple robes, their body-guards, the inclination of their necks and their louder tones in conversation, Pyrrhus, and Pyrrhus alone, [emulated him] in arms and action”, (‘Life of Pyrrhus’, 8: 1).

In fact, while Pyrrhus might have improved his reputation in this encounter, he did nothing to weaken Demetrius’ hold on Macedonia. However, Demetrius’ ambitions extended more widely: according to Plutarch:

“... his purpose was nothing less than the recovery of all the realm that had been subject to his father. Moreover, his preparations were fully commensurate with his hopes and undertakings. He had already gathered an army which numbered 98,000 foot and nearly 12,000 horsemen and, moreover, he had laid the keels for a fleet of 500 ships, some of which were in Piraeus, some at Corinth, some at Chalcis, and some at Pella. And he would visit all these places in person, directing what was to be done and aiding in the plans, while all men wondered ... at the multitude... [and] magnitude of the works. Up to this time, no-one had seen a ship of 15 or 16 banks of oars”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 43: 2-4)

According to Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn (referenced below, at p. 364), these preparations were well underway by 288 BC. Unsurprisingly, Lysimachus, Seleucus, Ptolemy and Pyrrhus soon agreed to defeat Demetrius at any price:

✴Ptolemy's fleet soon appeared off Greece, inciting the cities to revolt; and

✴Lysimachus attacked Macedonia from Thrace.

Demetrius, who was in Greece when he became aware of the danger, left Antigonus in charge of the war there and returned to Macedonia in order to confront Lysimachus. Pyrrhus used this opportunity to take the Macedonian city of Beroea, causing Demetrius to march in his direction and allowing Lysimachus to take Amphilipolis. As Demetrius approached Beroa, Pyrrhus sent men to infiltrate his camp and to prompt his army to desert him. According to Plutarch, when Demetrius became aware of:

“... the agitation in the camp, ... he secretly stole away ... So Pyrrhus came up, took the camp without a blow, and was proclaimed king of Macedonia”, (‘Life of Pyrrhus’, 11: 6)

Pyrrhus was, in fact, soon forced to share the rule of Macedonia with Lysimachus until 284 BC, when Lysimachus drove him out and incorporated almost all of Macedonia into his kingdom.

Demetrius’ Last Campaigns (288 - 282 BC)

Demetrius fled from Beroea to his court at Cassandreia, where his distraught wife, Phila, poisoned herself. He continued into Greece, where he still held a number of important cities, including Athens. However, he had been seriously undermined by his loss of Macedonia, and the Athenians took the opportunity to revolt in the spring 0f 287 BC. Demetrius laid siege to the city and the Athenians requested help from Pyrrhus, but it seems that Demetrius managed to leave Athens by sea for Asia Minor with the tacit agreement of both Pyrrhus and Ptolemy (see, for example, Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn, referenced below, at p. 404). Lysimachus (with the aid of his son, Agathocles) and then Seleucus were able to drive Demetrius ever eastwards until, in 285 BC, when he surrendered to Seleucus. At this point, he wrote to Antigonus and to his commanders in Athens and Corinth, telling them henceforth to consider him a dead man and to ignore any letters they might receive written under his seal. He was still Seleucus’ prisoner when he died, probably in early 282 BC (see Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn, referenced below, at p. 435). Seleucus sent Demetrius’ ashes to Antigonus, who was now a king without a throne.

Demetrius’ death marked the end of an era:

✴Ptolemy I had died a few months before him; and

✴in the following year:

•Seleucus invaded Lysimachus’ territory and defeated him at Corupedium (near Sardis) and Lysimachus was killed during the battle; and

•Seleucus was murdered shortly thereafter.

Read more:

Wheatley P., “Resolving a Persistent Chronographic Problem in the Early Hellenistic Period: SEG 36.165 and the ‘Special’ Eleusinian Mysteries of 303 BC”, Journal of Greco-Roman Studies, 59:3 (2020) 57-75

Wheatley P. and Dunn C., “Demetrius the Besieger”, (2020) Oxford

Davies S. H., “Rome, Global Dreams, and the International Origins of an Empire”, (2019) Leiden

McTavish J., “A New Chronology for Seleucus Nicator's Wars from 311–308 BC”, Phoenix, 73:1-2 (2019) 62-85

Robinson C. F., “Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult”, (2019) thesis of the University of Queensland

Wallace S., “The Freedom of the Greeks in the Early Hellenistic Period (337-262 BC): A Study in Ruler-City Relations”, (2011) thesis of the University of Edinburgh

Champion J., “Pyrrhus of Epirus”, (2009) Barnsley

Wheatley P., “Antigonid Campaign in Cyprus (306 BC)”, Ancient Society, 31 (2001) 133-56

Gruen E., “The Coronation of the Diadochi”, in

Eadie J. and Ober J.(editors), “The Craft of the Ancient Historian”, (1985) London, at pp. 253-71

O’Sullivan L., “The Regime of Demetrius of Phalerum in Athens, 317-307 BC: A Philosopher in Politics”, (2009) Leiden and Boston