Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Philip II of Macedonia:

III: Creation of Philip’s Kingdom (360 - 355 BC)

Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Philip II of Macedonia:

III: Creation of Philip’s Kingdom (360 - 355 BC)

Kingdom of Macedonia (red) as Phillip II inherited it

From the page of the website historyofmacedonia.org

Philip Secures his Accession (360 - 359 BC)

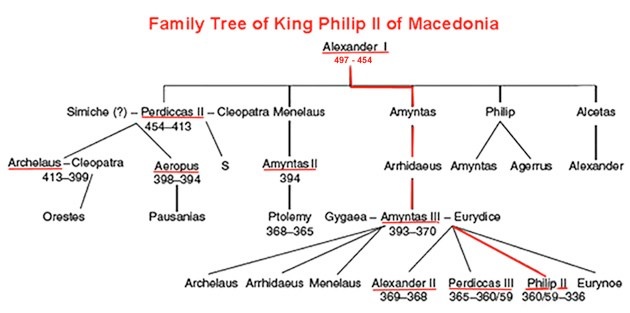

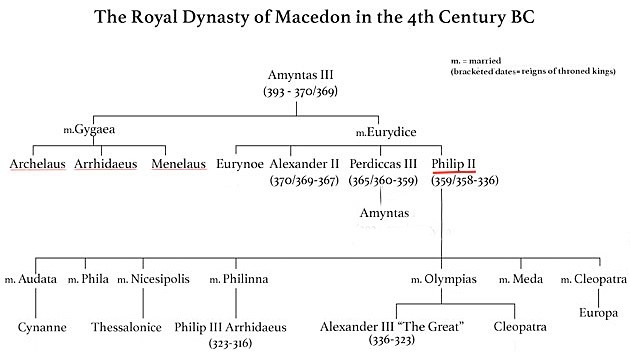

Royal Descent of Philip II

Adapted from Joseph Roisman (referenced below, fig. 8.1, at p. 157), my additions in red

Philip took the Macedonian throne in 360/359 BC, when his older brother, Perdiccas III, was killed in a battle with King Bardylis I of Illyria. Although he was still a young man whose military abilities were unproven, he was (like his two older brothers) a direct descendant of Alexander I, he did not belong to the ‘senior’ branch of the family.

Philip’s Competitors for the Throne

As Peter Green (referenced below, at p. 22) observed, despite Philip’s dynastic claim to the throne:

“Few political experts of the day ... can have given the new king [or regent] much more that six months, even at the shortest odds:

✴ ... a large proportion of [the Macedonian army had died on his western frontier] and Bardylis [was] preparing for a mass invasion;

✴the Paeonian [tribes of upper Macedonia] had already begun swarming down from the north to pillage [his territory in lower Macedonia, shown in red on the map above]; and

✴... [he faced] no fewer than five would-be usurpers ... :

•Pausanias of Lyncestis, [who] had secured Thracian backing;

•Argaeus, ... [who] was now assembling a sizeable force at Methone and had promised to cede Amphipolis to the Athenians in return for their backing - see below]; and

•... [his] three illegitimate brothers:

-Archelaus, [whom he quickly executed]; and

-Arrhidaeus and Menelaus, [who fled to Olynthus] ...”

However, as Diodorus Siculus explained, Philip quickly employed his well-honed diplomatic skills in order to protect his position:

“For instance, when he observed that the Athenians were centring all their ambition upon recovering Amphipolis and for this reason were trying to bring Argaeus back to the throne, he voluntarily withdrew [the Macedonian garrison] from the city, having first won [the loyalty of its citizens by pronouncing them to be] autonomous. He then:

✴sent an embassy to the Paeonians and, by corrupting some with gifts and persuading others by generous promises, he made an agreement with them to maintain peace for the present; and

✴... prevented the return of Pausanias by winning over with gifts the [the unnamed Thracian] king who was on the point of attempting his restoration”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 3: 3-4).

That essentially left Argeus and his Athenian backers who, as Diodorus recorded:

“... had dispatched Mantias as general with 3,000 hoplites and a considerable naval force [to Methone in order to support Argaeus]”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 2: 5).

However, it seems that this threat also quickly evaporated: Diodorus noted that:

“Mantias ... [remained at] Methone ... but sent Argaeus with his mercenaries to Aegae. Argaeus approached the city and invited the population of Aegae to welcome his return and become the founders of his own kingship, [but], when no one paid any attention to him, he turned back to Methone. [However], Philip ... suddenly appeared with his soldiers, engaged him in battle, killed many of his mercenaries and released the rest under a truce ... after [they had handed over to him the Macedonian exiles who had fought alongside them]”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 3: 5-6).

It seems that, at this point, Philip was keen to placate the Athenians; thus, the Athenian orator and politician Demosthenes would later reminded his fellow-citizens that:

“At the time when, having caught some of our citizens in the act of trying to restore Argaeus, [Philip]:

✴released them and made good all their losses; and

✴... professed in a written message that he was ready to form an alliance with us and to renew his ancestral amity ...”, (‘Against Aristocrates’, 23: 121).

Thus, in less than a year, Philip’s brilliant diplomacy had essentially secured his hold on lower Macedonia.

Victory over Bardylis I of Illyria (358 BC)

In 358 BC, Philip was able to subjugate the tribes of upper Macedonia and then to engage with Bardylis in the Erigon Valley: according to Diodorus:

“... the battle was [initially] evenly poised because of the exceeding gallantry displayed on both sides ... ; but later, as the horsemen pressed on from the flank and rear and Philip with the flower of his troops fought with true heroism, the mass of the Illyrians was compelled to take flight. When the pursuit had been kept up for a considerable distance and many had been killed as they fled, Philip recalled the Macedonians with the trumpet and, erecting a trophy of victory [on the battle field], buried his own dead. The Illyrians, having sent ambassadors and withdrawn from all the Macedonian cities, obtained peace: more than 7,000 Illyrians were killed in this battle, following which, Bardylis withdrew from western Macedonia”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 4: 6-7).

Philip had now avenged the death Perdiccas and won his first major battle, thereby securing his northern and western borders. (If he had started his reign as regent for Perdiccas’ young son Amyntas, he was certainly recognised as Philip II of Macedonia from this point). As we shall see, his marriage to Audata of Illyria probably took place at this time, as part of his peace deal with Bardylis.

Seizure of Amphipolis and Pydna (358 BC)

As we have seen, the Athenians had a particular concern about the status of the coastal polis of Amphipolis, which was located on the border between lower Macedonia and Thrace. It had once been been an Athenian colony, but had declared its independence in 424 BC and secured the protection of a Macedonian garrison from Perdicas III in the 360s BC. As we have seen, Philip had withdrawn the Macedonian garrison in 359 BC in order to encourage the Athenians to withdraw their support from the pretender Argaeus. However, within months, at least some factions in Amphipolis had apparently become concerned about’s Philip’s intentions, causing Demosthenes to record that, in 358 BC:

“... Hierax and Stratocles, the envoys of Amphipolis, mounted this platform and bade you sail and take over their city. If we had shown the same earnestness in our own cause as in defence of the safety of Euboea, Amphipolis would have been yours, at once and you would have been relieved of all your subsequent difficulties”, (‘First Olynthiac’, 1: 8).

Demosthenes was later to claim that, on this occasion, Philip had:

“... won our simple hearts by promising to hand over Amphipolis to us and by negotiating the secret treaty that was once so much talked about”, (‘Second Olynthiac’, 2: 6).

Scholars usually associate this passage from Demosthenes with a passage attributed to Theopompus:

“... and he sends to Philip ambassadors, Antiphon and Charidemus, to negotiate an alliance. When they arrived, they tried to persuade [Philip] to act in a secret alliance with the Athenians, so that they should take Amphipolis, promising him Pydna. But the ambassadors said nothing to the Athenian people, wishing to keep it a secret from the people of Pydna, as they intended to betray them, but acted in secret with the council (boule)”, (FGrH 115 F30).

Whatever the truth of this somewhat bizarre allegations, we know form Diodorus that, soon after Philip’s victory over Bardylis, he discovered (or perhaps claimed to have discovered) that, despite his recent recognition of their independence:

“... the people of Amphipolis were ill-disposed toward him and offered many pretexts for war. He [therefore] began a campaign against them with a considerable force. ... [After a short siege], he succeeded in breaching a portion of the walls ... [and] obtained the mastery of the city ... [after which], he exiled those who were disaffected towards him, while treating the rest considerately. ... [Thereafter, he] immediately:

✴reduced Pydna, [which the Athenians had seized in 364 BC]; and

✴made an alliance with the Olynthians [(see below)]... ”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 8: 2-3).

Thus, Philip secured complete control of his southern coast, from Pydna in the west to Amphipolis in the east. However, he had clearly damaged his relationship with the Athenians, and it seems that they actually declared war: for example, Aeschines (a political enemy of Demosthenes) later referred to:

“... the time of our war with Philip over Amphipolis, [which Demosthenes dates from Philip’s seizure of Amphipolis in 357 BC to] the peace and alliance that were made between Philip and the Athenians] on a motion of Philocrates [in 346 BC] ...”, (‘Against Ctesiphon’, 3: 54).

As Ian Worthington (referenced below, 2013, at p. 63), this was simply a face-saving gesture on the part of the Athenians.

Chaido Koukouli-Chrysanthaki (referenced below, at pp. 417-8) observed that:

“In Amphipolis, Philip II experimented for the first time with the incorporation of a Greek city-state into the Macedonian kingdom. ... [Philip initially seems to have made at least three important concessions to the formerly powerful city:

✴the functioning of the city government after the surrender to Philip;

✴the continuing issuance of silver and gold coins; and

✴the appearance, immediately after the seizure of the city, of a series of bronze coins.

... Nevertheless, the presence of Macedonian royal power can be deduced from:

✴the appearance of the same person as epistates for several years after the seizure of the city;

✴the installation of the priest of Asclepios as the new eponymous archon; and

✴the adoption of the Macedonian calendar.

The later cessation of the civic coinage and the replacement of the Amphipolitan drachma by Philip’s gold stater has also been attributed to an administrative reform of Philip II rather than to ‘an expression of sovereignty’. [In short], Amphipolis [became] a strong Macedonian fortress on the eastern boundary of the kingdom of Macedon and was the seat of a royal mint from as early as 357/6 BC.”

Alliance with King Arybbas of Molossia (357 BC)

According to Pompeius Trogus (as epitomised by Justinus), at about this time, Philip:

“... married Olympias, daughter (sic) of Neoptolemus, afterwards king of the Molossians. Her cousin (sic) Arybbas, then king of that nation, ... had brought up the young princess and had married her sister, Troas”, (‘Epitome of Pompeius Trogus' Philippic Histories’, 7: 6: 8-9).

I discuss this along with Philip’s other marriages below. For the moment, we should note that Arybbas ruled one of the three main tribes of Epirus, alongside:

✴the Chaonians (to the north-west); and

✴the Thesprotians (to the south-west and along the coast).

The passage above represents the only surviving evidence for the agreement of an alliance at this time between Philip and Arybbas (whose Molossian kingdom was located on Philip’s western border). It probably reflected the fact that Molossia, like Macedonia, had recently suffered from Illyrian aggression, as evidenced by the Roman strategist Frontinus, who noted (in a passage on ambushes) that:

“When [Arybbas], king of the Molossians, was attacked in war by Bardylis, the Illyrian, who commanded a considerably larger army, he dispatched the non-combatant portion of his subjects to the neighbouring district of Aetolia and spread the report that he was yielding up his towns and possessions to the Aetolians. [Meanwhile], he ... placed ambuscades ... on the mountains and in other inaccessible places. The Illyrians, fearful lest the possessions of the Molossians should be seized by the Aetolians, in their eagerness for plunder, began to race along in disorder. As soon as they became scattered, [Arybbas], emerging from his concealment and taking them unawares, routed them and put them to flight”, (‘Stratagems’. 2: 5: 19).

With this alliance with Arybbas of Molossia, Philip secured the western border of his new, cohesive kingdom Macedonia.

Olynthus and the Chalcidian League (358 BC)

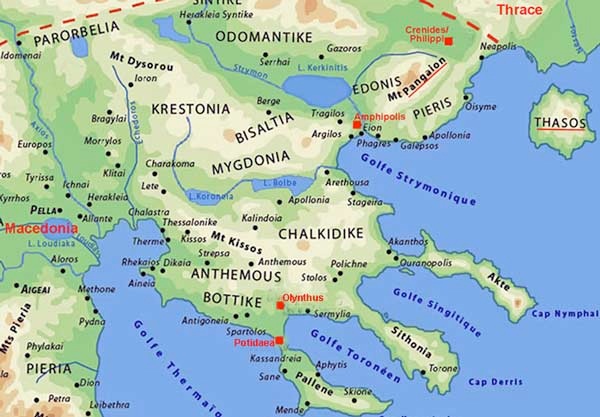

Map of Chalcidice (from Richard Gabriel, referenced below, Map 5, my additions in red)

At the time that Philip came to power, most of the Greek cities of the Chalcidic peninsula on his southeastern border belonged to a confederation known as the Chalcidian League, under the leadership of Olynthus. As Diodorus explained:

“The Olynthians inhabited an important city that, because of its huge population, had great influence in war. Their city was therefore an object of contention for those who sought to extend their supremacy and, for this reason, the Athenians and Philip were rivals ... for the alliance with them”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 8: 4).

Diodorus had previously recorded that, after Philip had taken Amphipolis and Pydna, he had:

“... made a treaty with the Olynthians in which he agreed to win for them the [nearby] city of Potidaea, [which the Athenians had seized and colonised in 361 BC] ... ”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 8: 3).

The existence of this treaty is confirmed by the surviving fragments of an inscription from Olynthus, which dates it to late 357 or early 356 BC (translated by Peter Rhodes and Robin Osborne, referenced below, inscription 50, at pp. 244-7). Furthermore, it seems that Philip had also promised the territory of Anthemus to the Olynthians: Demosthenes (in a speech that he gave against Philip in 344 BC) asked his audience to imagine:

“... how annoyed the Olynthians would have been to hear anything said against Philip [in 357 BC], ... when he was:

✴handing over to them Anthemus, to which all the former kings of Macedonia laid claim; and

✴making them a present of Potidaea, expelling the Athenian settlers ...”, (‘Second Philippic’, 6: 20).

As we shall see, made good his promise to capture Potidaea for the Olynthians in 356 BC.

Seizure of Crenides/ Philippi (358 BC)

Philip’s Move Towards Thrace (adapted from Wikipedia, my additions in red)

Diodorus recorded that, after his success at Potidaea, Philip

“... went to the city of Crenides and, having increased its size with a large number of inhabitants, changed its name to Philippi, giving it his own name. He then turned to the gold mines in their territory, which were very scanty and insignificant [at that time]; he increased their output so much by his improvements that they could bring him a revenue of more than 1,000 talents. He soon amassed a fortune and was able to strike the gold coins that came to be known from his name as Philippi. With these, [he was able] to raise a large force of mercenaries and to bribe many Greeks to become betrayers of their native lands ... ”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 8: 6-7).

With Amphipolis and the Chaldician peninsula now under his control, Philip would surely have appreciated an opportunity to seize the mines in the Pangaion Hills and, at the same time, to secure part of his border with Thrace: Philippi became the first Macedonian colony, and the mines there became a major source of revenue for the kingdom.

The background to this development can be fleshed out from other surviving sources. Diodorus himself had earlier recorded that, soon after Philip’s defeat of Argaeus in 359 BC, the people of the island of Thasos had:

“... settled the place called Crenides, which the king afterward named Philippi for himself and made a populous settlement”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 3: 7).

According to Earl McQueen (referenced below, at p. 76), Stephanus of Byzantium, in his entry on Philippi, suggested that these colonists had appealed to Philip for aid when they were being attacked by ‘the Thracians’. At this time (as we shall see in more detail in the following page), Thrace was ruled by three kings:

✴Cetriporis in the east

✴Amadocus in the centre; and

✴Cersobleptes in the west.

McQueen (as above) observed that the Thracians who allegedly attacked Crenides:

“... may possibly have been the subjects of Cetriporis, who had succeeded Berisades as king of the most westerly of the three [Thracian] kingdoms, but were more probably acting under orders from Cersobleptes of eastern Thrace, in a bid to secure funds [from the mines here] for his bid to secure control of [the kingdoms of Amadocus and Cetrporis].”

It is, of course, possible that the story of the Thracian attack on Crenides and the colonist’s appeal to Philip was manufactured as camouflage for Philip’s aggression.

Chaido Koukouli-Chrysanthaki (referenced below, at pp. 439-40) observed that:

“The new settlers [at Philippi] came not so much from Macedon as from villages in the area around Crenides. Most of them must have been of Ionian descent, as a result of the strong presence of Thasians in the Thasian Perea and the expansion of the Athenians’ influence there. Macedonian names are scarce in inscriptions from the new city, both facts implying a preponderance of Ionian elements in the population. The Thasian alphabet on the funeral stele of Demetria is connected with Thasian settlers of Crenides, and the Athenian names in inscriptions from Philippi have been attributed recently to a substantial Athenian participation in the first foundation of Crenides, surviving into its re-foundation by Philip II. Philippi was transformed into a strategic base for Philip’s campaigns in Thrace, and was the focus for the mining activity that he developed in the region. It is not clear whether there was a royal mint at Philippi (as there was at Amphipolis and at Pella), but the city of Philippi, although part of the Macedonian kingdom, continued to mint its own independent coinage in gold, silver, and bronze until the reign of Alexander the Great. It continued to use the designs of the [earlier] coins of Crenides, which derived, in turn, from Thasian types: the head of Heracles stood on the obverse, and Apollo’s tripod on the reverse, together with the legend ΦΙΛΙΠΠΩΝ [(PHILIPPON)].”

Intervention in Thessaly (357/6 BC)

Poleis of Thessaly ((adapted from this webpage on the coins of Thessaly in 4th century BC, my additions in red)

The Greek poleis of Thessaly (on Philip’s southwestern border) were independent entities generally ruled by local aristocrats, although they operated collectively in respect of their membership of the the Amphictyonic Council at Delphi. In the period ca. 375-70 BC, they had elected the redoubtable Jason of Pherae as tagos, which made him the overall commander of their armies. As Sławomir Sprawski (referenced below, 2020) observed:

“This was the crucial step in Jason’s plan to transform the weak Thessalian League into a powerful and efficient state able to challenge Sparta and Athens in pursuit of hegemony over mainland Greece. A skilful diplomat, Jason secured his position by:

✴holding the balance of power between Sparta and Athens;

✴... [controlling] King Alcetas [I of Molossia, Arybbass’ father]; and

✴[making] and alliance with [King] Amyntas III of Macedonia.

I discuss these events in the following page because they formed the backdrop to Philip’s important relationship with Thessaly. For the moment, we should merely note that, when Jason was assassinated in 370 BC, the Thessalian poleis (principally Larissa and Pharsalus) re-asserted their independence.

Philip’s first opportunity to involve himself in Thessalian affairs came in in 357/6 BC, when, according to Diodorus, a conflict broke out there between the leaders of Pherae and Larissa: as Diodorus explained:

“... Alexander, tyrant of Pherae [had been] assassinated by his own wife Thebe, [at the behest of] her brothers Lycophron and Tisiphonus. The brothers initially received great acclaim as tyrannicides. However, having changed their purpose and bribed the mercenaries [who had been employed by Alexander ?], they revealed themselves to be tyrants, killed many of their opponents and ... governed by force. At this point, the Thessalian faction among the Aleuadae [of Larissa] ... began to oppose them and (not being of sufficient strength to fight by themselves) allied themselves with Philip, the king of the Macedonians”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 14: 1-2).

It will be useful here to say a little more about the Thessalians who feature in this paragraph:

✴those from Pherae were related to Jason of Pherae:

•Thebe and her brothers, Lycophron, Tisiphonus and Pitholaus, were his children or step-children (see, for example, Cinzia Bearzot, referenced below, at p. 5 and note 3); and

•Alexander was the son of his brother, Polydorus (see, for example, Peter Rhodes and Robin Osborne, referenced below, inscription 44, at p. 222); and

✴the Aleudae were the traditional dynastic rulers of Larissa.

It seems then that the Larissans (and probably other Thessalian poleis) sought Philip’s intervention because they feared that Lycophron and Tisiphonus threatened their independence.

According to Diodorus:

“On entering Thessaly, [Philip]:

✴defeated the tyrants [of Pherae, although, as we shall see, he did not expel them];

✴restored the independence of the [other Thessalian] cities; and

✴showed himself very friendly to the Thessalians, to the extent that, in the course of subsequent events, not only Philip himself but but also his son [and successor], Alexander, always had the Thessalians as confederates”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 14: 1-2).

As Earl McQueen (referenced below, at p. 78) observed:

“The silence of our [surviving] sources on further incidents in Thessaly until 353/2 BC [(discussed on the following page) suggests that, on this occasion], ... Philip was [merely effected] a temporary reconciliation between the warring factions.”

As discussed below, Philip’s marriage to Philinna of Larissa must have taken place at about this time. (Some scholars argue that his marriage to Nicesipolis of Pherae was also contracted during this visit, but, as we shall see, this is unlikely.)

More generally, Philip would surely have valued an opportunity to establish strong relations with all of the Thessalian factions at this time, if only to counter the potential threat to his southern border from:

✴the Thebans, who had been influential in Thessaly for at least a decade; and

✴the Athenians, who had had an alliance with:

•Alexander of Pherae in 368 BC; and

•his Thessalian enemies (who self-identified as the ‘koinon of Thessaly’) in 361/60 BC.

(See Peter Rhodes and Robin Osborne, referenced below, inscription 44, at pp. 218-21 for details of these alliances).

Interestingly, the Athenian Isocrates probably referenced an extant alliance between Athens and the tyrants of Pherae in a letter that he wrote to ‘the children of Jason’, probably in 355/4 BC (see, for example, Cinzia Bearzot, referenced below, at p. 6 and Peter Rhodes and Robin Osborne, referenced below, inscription 44, at p. 225). Isocrates began by observing that one of the envoys whom the Athenian had sent to Pherae:

“... has brought me word that you, summoning him apart from the others, asked whether I could be persuaded [leave Athens] and reside with you. And I, for the sake of my friendship with Jason and Polyalces, would gladly come to you. [However, I must decline for a number of reasons, including your present alliance with] Athens, since the truth must be told; for I see that alliances made with [Athens] are soon dissolved. So, if anything of that kind should happen between Athens and you,... I do not see how I could please both sides. Such, then, are the reasons why I cannot do as I wish”, (‘Letter to the Children of Jason [of Pherae]’, 6: 3).

However, there is no surviving evidence of any Athenian involvement in support of the Phereans on this particular occasion.

Events of 356 BC

According to Plutarch, Philip:

“... who had just taken Potidaea, received three messages at the same time:

✴the first announced that Parmenion, [Philip’s leading general], had conquered the Illyrians in a great battle;

✴the second announced that his horse had won a victory in the κέλης (keles, horse race event) at the Olympic games; and

✴the third announced the birth of Alexander”, (‘Life of Alexander’, 3: 5).

I discuss the military campaigns of Philip and Parmenion in 356 BC in the sections below and return to:

✴Philip’s Olympian victory of 356 BC in the section below on his early coinage; and

✴the birth of his heir, Alexander, in the section below on his early marital diplomacy.

Capture of Potidaea

As we have seen, Diodorus recorded that Philip had promised to capture Potidaea for the Olynthiansin 357 BC. Earl McQueen (referenced below, at p. 75), who dated the fall of Potidaea to 356 BC, observed that:

“... neither Diodorus nor any other [surviving] source preserves details of the siege [of Potidaea].”

However, as a postscript to his account of Philip’s agreement with the Olynthians, Diodorus had recorded that:

“... Philip, when he had forced Potidaea to surrender, led the Athenian garrison out of the city and, treating it considerately, sent it back to Athens (for he was particularly solicitous toward the people of Athens on account of the importance and repute of their city). [Then], having sold the [other] inhabitants [of the city] into slavery, he handed it over to the Olynthians, along with all the properties in the territory of Potidaea”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 8: 5).

It also seems that the Athenians had made an unsuccessful attempt to forestall him: in a speech that Demosthenes gave in ca. 351 BC urging action against Philip (see below), he complained to the Athenian assembly that:

“ ... your expeditions invariably arrive too late, whether at Methone [(see below)] or at Pagasae [(see below)] or at Potidaea ...”, (‘First Philippic’, 4: 36).

As Ian Worthington (referenced below, 2008, at p. 43) argued that:

“... the real reason for [the Athenians’] apathy was the revolt of [their] allies ... in 356/5 BC. This [revolt] is commonly called the Social War and, in it, we may plausibly see Philip at work.”

Revolt of the Thracians, the Paeonians and the Illyrians

According to Diodorus recorded that, in 356/5 BC:

“... the kings of the Thracians, the Paeonians and the Illyrians combined against Philip. These peoples, whose territories all bordered on Macedonia, all eyed Philip’s recent expansion with suspicion. ... [He had defeated each] of them ... in the past, but they imagined that, if they should join their forces in a war, they would easily have the better of [him]. However, while they were still gathering their armies, Philip appeared before their dispositions were made, struck terror into them, and compelled them to join forces with the Macedonians”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 22: 3).

As it happens, we know the names of these three (deluded) kings: surviving fragments of an inscription (translated by Peter Rhodes and Robin Osborne, referenced below, inscription 53, at pp. 254-7) from Athens indicate that it originally recorded an alliance that the Athenians made in July 356 BC with:

✴King Cetriporis of Thrace and his [otherwise unknown] brothers;

✴King Lyppeus of Paeonia; and

✴King Grabus of Illyria.

Cetriporis of Thrace

As Earl McQueen (referenced below, at p. 85) observed, this treaty:

“... postdates Philip’s capture of Crenides, which the coalition promises to recover (at line 45).”

It seems likely that Philip would have moved against Cetriporis as soon as he became aware of this treaty: as Earl McQueen observed:

“As we hear of no further hostilities against Cetriporis at this time, he ... may have come to terms [with Philip]. as Diodorus says.”

Grabus of Illyria and Lyppeus of Paeonia

As noted above, Plutarch recorded that Parmenion had conquered the Illyrians ‘in a great battle’. This presumably refers to a victory over King Grabus. Since Philip must have been fully occupied with the campaigns at Potidae, Crenides and western Thrace at this time, it seems likely that it was Parmenion who defeated Lyppeus. There is no reason to doubt that these two kings agreed terms of some sort in 356 BC although, as we shall see in the following page, Philip apparently campaigned again against ‘the Paeonians and the Illyrians’ in 351/0 BC.

Capture of Methone (355-4 BC)

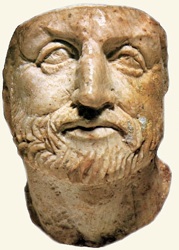

Ivory head (4th century BC), usually thought to depict Philip II

from Tomb II at Aegae, now in the Polycentric Museum of Aigai (modern Vergina)

The image is from this article by Martin Anastasovski (2021) in the Macedonia Times

As Ian Worthington (referenced below, 2008, at p. 48) observed, after Philip’s capture of Pydna in 357 BC (above), Methone was the only city on his seaboard that he did not control. However, in what Worthington reasonably characterised as an enigmatic statement, Diodorus recorded that, in ca. 355 BC:

“... Chares, the Athenian general, sailed to the Hellespont, captured Sestos [on the Chersonese], killed its adult inhabitants and enslaved the rest. And when Cersobleptes, son of Cotys, because of his hostility to Philip and his [subsequent] alliance of friendship with the Athenians, turned over to the Athenians all of the cities on the Chersonese except Cardia, the [Athenian] assembly sent out cleruchs (settlers) to these cities. Philip, perceiving that the people of Methone were permitting their city to become a base of operations for his enemies, began a siege [there]”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 34: 4).

I discuss the Athenians’ actions in the Chersonese on the following page: for the moment, we should note that Diodorus did not explicitly link these actions to those of Philip’s unnamed enemies at Methone. However, the likelihood is that, as in 359 BC, this city had become a base for Philip’s Macedonian enemies, and that he feared that they might call on the Athenians for support in an attempt to seize his throne: as we have seen, Demosthenes would later observe that Athenians had indeed sent a military force of some kind to Methone after the siege had started, albeit that it had arrived too late.

According to Ian Worthington (referenced below, 2008, at p. 49), Philip’s siege of Methone began in the winter of 355 BC and continued into the early summer of 354 BC. Diodorus recorded that:

“Although the people of Methone held out for a time, [they were subsequently] overpowered ... [and] compelled to hand the city over to [Philip] on the terms that the citizens should leave with only a single garment each. Philip then razed the city and distributed its territory among the Macedonians. In this siege it so happened that Philip was struck in the eye by an arrow and lost the sight of that eye”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 34: 4-5).

Pompeius Trogus (as epitomised by Justinus) also mentioned the eye wound in this context:

“After [his alliance with Arybbas], Philip, no longer satisfied with acting on the defensive, boldly attacked even those who gave him no cause. While he was besieging Methone, an arrow, shot from the walls at him as he was passing by, struck out his right eye; but he was neither rendered less active in the siege, nor more resentful towards the enemy by this wound, to the extent that, some days after, he granted them peace when they asked for it and was not only not severe, but even merciful, to the conquered”, (‘Epitome of Pompeius Trogus' Philippic Histories’’, 7: 13-6).

Philip’s War Wounds

Demosthenes, in a speech that he delivered in 330 BC (some six years after Philip’s death) observed that, in his quest:

“... for empire and supremacy, ... [Philip] endured the loss of his eye, the fracture of his collar-bone, the mutilation of his hand and his leg, and was ready to sacrifice any and every part of his body to the fortune of war, if only the life of the shattered remnant should be a life of honour and renown”, (‘On the Crown’, 18: 67-8). As we have seen, one of the things that people remembered about Philip after his death was the fact that he had survived many wounds that would have incapacitated or killed many lesser men:

Alice Swift Riginos (referenced below, at p. 105) observed that Demosthenes’:

“... celebrated image of [Philip’s] battered and scarred,,, body was a main source of inspiration for [later fabricated] 'biographical' material about [his many] injuries. ... [It] suggested to at least one ancient reader that Philip [received] his wounds simultaneously. ... [However, other sources] make it clear ... that the injuries were received on different campaigns ... :

✴the eye was wounded at Methone,

✴the collar bone in fighting against the Illyrians; and

✴the leg and arm in fighting against the Scythians.

Once the campaigns are specified, it is obvious that Demosthenes listed the injuries in chronological order: [Philip]:

✴[lost his eye at] Methone (354 BC);

✴[injured his collar bone in Illyria] (344 BC); and

✴[injured his leg and arm in Scythia] (339 BC).”

I discuss the last two of these woundings in following pages.

Philip’s Eye Wound

Didymus (1st century BC) provided further details of the eye wound in his commentary on the published speeches of Demosthenes:

“... at around the time of the siege of Methone, [Philip] lost his right eye when he was struck by an arrow while overseeing the siege engines and their ‘sheds’, just as Theopompos narrates in (Book 4) of his [‘Philippika’]. On this matter, Marsyas agrees”, (‘On Demosthenes’, column 12, based on the translations by Phillip Harding, referenced below, at p. 87 and Alice Swift Riginos, referenced below, at p. 106).

Didymos’ first source, Theopompos of Chios (4th century BC) wrote his biography when Philip was still alive and, as Alice Swift Riginos (referenced below, at pp. 106-7) observed, he:

“.. may have been a visitor to Philip's court at Pella; it is surely safe to [accept] that the details that he recorded of Philip's wounded eye summarised the version approved by, and circulated in, Macedonian court circles.”

As Ian Worthington (referenced below, 2008, at p. 49) observed, the small ivory head that was found in a tomb at Vergina (illustrated above) might well represent Philip, since its subject:

“... has a facial disfigurement around the right eye, which also appears sightless.”

Philip’s Marital Diplomacy (359-5 BC)

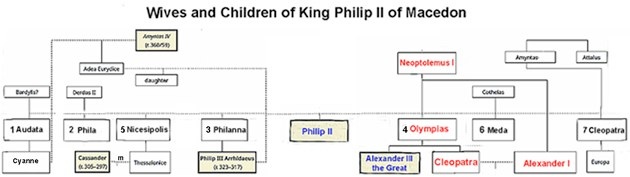

Family of Philip II

Adapted from the image in this webpage by David Grant (2020)

Philip was famously polygamous, and his marriages famously played a key role in the diplomatic offensive that ran alongside his military campaigns. The only surviving source that claims to provide a comprehensive list of these marriages and the resulting offspring is Athenaeus (ca. 200 AD), according to whom:

“As Satyrus [ca. 200 BC] says in his biography of [Philip]:

‘In the 22 years [sic - see below] he was king, he married:

✴Audata the Illyrian, who bore him a daughter, Cynna;

✴Phila [of Elimeia in western Macedonia, on the border with Thessaly], the sister of Derdas and Machatas; and

✴two Thessalian women (since he wanted to win over the Thessalian people):

•... Nicesipolis of Pherae, who bore him [a daughter], Thessalonice; and

•... Philinna of Larissa, who bore him [a son], Arrhidaeus.

✴He also added the kingdom of the Molossians to his possessions [in 357 BC] by marrying Olympias, who bore him:

•[a son], Alexander [of Macedonia]; and

•[a daughter], Cleopatra [of Molossia].

✴When he conquered Thrace, Cothelas, the king of the Thracians, came over to him, bringing him his daughter Meda [in 342 BC] ... whom] he brought into his household besides Olympias.

✴In addition to all these, he married Cleopatra, the sister of Hippostratus and niece of Attalus, having fallen in love with her. When he brought [Cleopatra] into his household beside Olympias [in 337 BC], he threw his whole life into confusion’”, (‘Deipnosophists’, 8: 557 b-d, translation based on those by Adrian Tronson, referenced below, at pp. 119-20 and Miltiades Hatzopoulos, referenced below, at p. 138).

Miltiades Hatzopoulos (referenced below, at p. 128) argued that Athenaeus was probably mistaken in saying that Philip ruled for 22 years: he almost certainly:

✴acceded to the throne when he was 22 years old; and

✴actually ruled for 24 years, before his death in 336 BC.

Hatzopoulos also pointed out (at pp. 138-9) that only three of Philip’s marriages in Satyrus’ list (as transmitted by Athenaeus) can be securely dated:

✴to Olympias, in 357 BC;

✴to Meda, in 342 BC; and

✴to Cleopatra of Macedonia, in 337 BC.

He also argued (at p. 140 and notes 102-4) that, pace Adrian Tronson (above), the marriages in this list were not necessarily given in chronological order and, in particular, that Philip probably married Nicesipolis at some time after his marriage to Olympias (see below).

Elizabeth Carney (referenced below) , in her detailed book on the women of the Macedonian court, suggested that:

✴Audata of Illyria was probably closely related to Bardylis, and that Philip probably married her shortly after his victory over Bardylis in 358 BC (see pp. 57-8);

✴Philip’s marriage to Phila of Elimeia probably took place at about the same time, when he was intent on bringing the tribes of upper (western) Macedonia under his control (see pp. 59-60);

✴his marriage to Nicesipolis probably took place before his marriage to Olympias (see pp. 60-1, although other scholars ague for a much later date - see below);

✴his marriage to Philinna of Larissa must have taken place in 358-7 BC (presumably when he was in Thessaly), since their son, Arrhidaeus, was of marriageable age by 336 BC (see pp. 61-2); and

✴since Alexander of Macedonia, Philip’s son by Olympias, was born in June 356 BC, this marriage must have taken place in or before 357 BC (see p. 63).

Date of Philip’s Marriage to Nicesipolis of Pherae

As Elizabeth Carney (referenced below, at p. 60) pointed out, Stephanus of Byzantium (in his entry on Thessalonice):

“... explicitly states that Philip married [rather than merely slept with] Nicesipolis ... and cites Lucius the Tarraian for the fact that she was ... the niece of Jason of Pherae. He [also] relates that Nicesipolis died 20 days after the birth of her daughter and that Philip named [this] daughter [Thessalonice] after his victory in Thessaly.”

The most reliable way of dating Nicesipolis’ marriage and the birth of Thessalonice is to look at the events of Thessalonice’s later life. Diodorus recorded that, in ca. 316 BC, some 20 years after Philip’s male line had ended with the death of his son, Alexander, Cassander, the son of Antipater (a general under both Philip and Alexander):

“... began to entertain hopes of winning the Macedonian kingdom. For this reason he married Thessalonice, who was Philip's daughter and Alexander's half-sister, since he desired to establish a connection with the royal house”, (‘Library of History’, 19: 52: 1).

Cassander was subsequently able to declare himself King of Macedoina in ca. 308 BC. According to Plutarch, after his death in 297 BC:

“... the eldest of his sons, Philip, reigned over the Macedonians for a only short time before he also died. The two remaining brothers quarrelled with one another over the succession. [In 294 BC]:

✴one of them, Antipater, murdered his mother, Thessalonice and

✴the other, Alexander, appealed for help from both Pyrrhus from Epirus and Demetrius from the Peloponnese”, (‘Life of Demetrius’, 36: 1).

Alexander, Thessalonice’s youngest son, must have been at least 18 in 294 BC (since he was a serious contender for the succession). This means that Thessalonice gave birth to three sons in ca. 316-2 BC, which suggests that:

✴she was almost certainly no older that 35 when she married Cassander in ca. 316 BC; and thus

✴she was born no earlier than ca. 351 BC.

As noted above, some scholars believe that Philip married both Nicesipolis of Pherae and Philinna of Larissa during his intervention in Thessaly in 357/6 BC (since, according to Athenaeus, he contracted both marriages because ‘he wanted to win over the Thessalian people’). However, this would mean that:

✴Nicesipolis was married to Philip for about six years before she gave birth to a child that survived into adulthood; and

✴that child, Thessalonice, married Cassander when she was about 40 and she then gave birth to three sons in about four years.

Since:

✴neither aspect of this scenario seems particularly likely; and

✴Philip had not secured a victory in Thessaly by 357/6 BC;

it seems to me that his marriage to Nicesipolis probably post-dated his victory over the Phocians in Thessaly in 352 BC (as discussed in the following page).

Philip’s Marriage to Olympias (ca. 357 BC)

Yellow boxes = kings of Macedonia; Red = Molossian

Adapted from Wikiwand

As we have seen, according to Pompeius Trogus (as epitomised by Justinus), in ca. 357 BC, Philip:

“... married Olympias, daughter (sic) of Neoptolemus, afterwards king of the Molossians. Her cousin (sic) Arybbas, then king of that nation, ... had brought up the young princess and had married her sister, Troas”, (‘Epitome of Pompeius Trogus' Philippic Histories’, 7: 6: 8-9).

In fact, as illustrated in the family tree above, Olympias was the daughter of King Neoptolemus I of Molossia. He had died by the time of her marriage, and the Molossian throne had passed to her uncle, Arybbas, who was by that time also her guardian and brother-in-law.

Although the precise date of her marriage is uncertain, we know from Plutarch (as already mentioned above) that she gave Philip a son, Alexander, in 356 BC. In fact. we can be more precise: Plutarch recorded that Olympias gave birth to Alexander, presumably at Pella:

“... early in the month Hecatombaeon, the Macedonian name for which is Loüs, on the sixth day”, (‘Life of Alexander’, 3: 5).

This allows us to date Alexander’s birth to late July 356 BC, which obviously means that Philip’s marriage to Olympias took place during or before October 357 BC. Olympias’ daughter, Cleopatra, must have been born soon after, since she married her uncle (Olympias’s brother, by then King Alexander of Molossia) in 336 BC.

Philip’s Marital Diplomacy (359-5 BC): Conclusions

Diplomatic marriages played an important role in Philip’s consolidation of his kingdom of Macedonia:

✴Philip’s marriage to Audata of Illyria probably took place as part of his peace deal with King Bardylis of Illyria in 358 BC. Their daughter, Cynna (0r, more usually, Cynane or Cynanne) went on to play an active part at Philip’s court (see, for example, Elizabeth Carnet, referenced below, at pp. 69-70 and Pasi Loman, referenced below, at p. 45).

✴Philip’s marriage to ‘Phila, the sister of Derdas and Machatas’ is usually assumed to have taken place at about this time. According to Robin Lane Fox (referenced below, at pp. 342-3), Phila

“... was the daughter of Derdas of Elimea [on the border of upper (western) Macedonia and Thessaly], whose capital at Aiane had not been occupied by the Illyrian raiders. From this canton came excellent cavalry and more manpower for the phalanx, troops that Perdiccas III (I suggest) had not tapped for his fatal battle [against the Illyrians]: Elimea, in my view, had remained unlinked to Perdiccas as late as 360 BC. Its co-operation now was to be a decisive factor [in Philip’s consolidation of his kingdom].”

Carol King (referenced below, at p. 73 argued that, given the high reputation of the Elmiote cavalry:

“... Philip probably did not go into battle in western Macedonia against the Illyrians without first reaffirming the long-standing alliance of [eastern] Macedonia with Elmeia, His marriage to Phila ... [probably] hinged on the incorporation of the [Elmiote] cavalry into his new army ...”

✴As discussed above, Philip’s marriage to Philinna of Larissa (in Thessaly) probably dated to 357/6 BC, when Philip intervened at the request of the Aleuadae of Larissa in their dispute with Lycophron and Tisiphonus, the sons of Jason of Pherae. Since, according to Athenaeus, he contracted both this marriage and his marriage to Nicesipolis ‘because he wanted to win over the Thessalian people’, Philinna, like Nicesipolis, must have been well-born. It seems to me that, by taking a wife from Larissa at this point, Philip was signalling to the tyrants of Pherae that he would intervene again, should they cause further problems for him in Thessaly. Philinna gave Philip a son, Arrhidaeus (later Philip Arrhidaeus) but he never seems to have been considered as a possible successor until the death of Philip’s other son, Alexander (see below). Since Philip proposed that he should marry the daughter of a Persian satrap in 336 BC, he must have been born before ca. 356 BC (although it is not clear whether he was slightly older or slightly younger than his brother).

✴As we have seen, Philip almost certainly married Olympias in 357 BC as part of a wider agreement with her uncle, King Neoptolemus I of Molossia and she gave him a son, Alexander, in late July 356 BC. While Philinna’s son Arrhidaeus was probably slightly older than Alexander, it seems that he was incapacitated in a manner that compromised his place in the line of succession. Thus, from the time of Alexander’s birth, Olympias, as the mother of Philip’s most likely successor, was probably the most important women at his court.

Read more:

Velaoras A., “Myth and History in the Court of Archelaus”, in:

Menelaos C. et al. (editors), “Myth and History: Close Encounters”, (2022) Berlin, at pp. 303-20

Sprawski S., “The Temenidae, Who Came Out of Argos: Literary Sources and Numismatic Evidence on the Macedonian Dynastic Traditions”, Notae Numismaticae, 16 (2021) 13-42

Hatzopoulos M. B., “Ancient Macedonia”, (2020) Berlin and Boston

Barker E. T. E. and Christensen J.P., “Homer's Thebes: Epic Rivalries and the Appropriation of Mythical Pasts”, Hellenic Studies Series 84 (2019) on-line (Center for Hellenic Studies, Washington DC

Sprawski S., “Jason of Pherai (Pherae)” ,Wiley Encyclopaedia of Ancient History (2020), on-line

King C., “Ancient Macedonia”, (2018) London and New York

Witmore C., “Complexities and Emergence: The Case of Argos”, in:

Knodell A.R. and Leppard T.P. (editors), “Regional Approaches to Society and Complexity: Studies in Honor of John F. Cherry”, (2017) London, at pp. 268-87.

Bearzot C., “Isocrate et Phères: Jason et ses Successeurs”, Ktèma: Civilisations de l'Orient, de la Grèce et de Rome Antiques, 41 (2016) 5-15

Worthington I., “Demosthenes of Athens and the Fall of Classical Greece”, (2013) Oxford and New York

Koukouli-Chrysanthaki C., “Amphipolis” and “Philippi”, in:

Lane Fox R. (editor), “Brill’s Companion to Ancient Macedon: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Macedon (650 BC–300 AD)”, (2011) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 409-36 and pp. 437-52 respectively

Lane Fox R., “Philip of Macedon: Accession, Ambitions, and Self-Presentation”, in:

Lane Fox R. (editor), “Brill’s Companion to Ancient Macedon: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Macedon (650 BC–300 AD)”, (2011) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 332-66

Gabriel R. A., “Philip II of Macedonia: Greater Than Alexander”, (2010) Washington DC

Roisman J., “Classical Macedonia to Perdiccas III”, in:

Roisman J. and Worthington I. (editors), “A Companion to Ancient Macedonia”, (2010) Malden, MA and Oxford, at pp. 145-65

Collard C. and Cropp M.. (translators), “Euripides: Fragments: Aegeus-Meleager”, (2008) Cambridge MA

Worthington I., “Philip II of Macedonia”, (20o8) New Haven and London

Harding P., “Didymos: On Demosthenes: Text and Commentary”, (2006) Oxford

Loman P., “No Woman No War: Women's Participation in Ancient Greek Warfare”, Greece & Rome, 51:1 (2004) 34-54

Rhodes P. and Osborne R., “Greek Historical Inscriptions (404-323 BC)”, (2003) Oxford and New York

West M. L. (translator), “Greek Epic Fragments (7th to the 5th Centuries BC)”, (2003) Cambridge MA

Carney E., “Women and Monarchy in Macedonia”, (2000) Oklahoma

McQueen, E. I., “Diodorus Siculus: the Reign of Philip II: The Greek and Macedonian Narrative from Book XVI”, (1995) London

Riginos A. S., “The Wounding of Philip II of Macedon: Fact and Fabrication”, Journal of Hellenic Studies, 114 (1994) 103-19

Green P., “Alexander of Macedon (356–323 BC): A Historical Biography”, (1991, 2nd edition 2013) Berkeley, Los Angeles and London

Tronson A., “Satyrus the Peripatetic and the Marriages of Philip II”, Journal of Hellenic Studies, 104 (1984) pp. 116-26