Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Alexander I: Thraco-Macedonian Context (II)

Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Alexander I: Thraco-Macedonian Context (II)

Coinage of Acanthus

‘Signed tetradrachm’ (17.14 gm.) of Acanthus (Desneux Period II, type 95, ex CNG Sale 54, 2000)

Obverse: Lion attacking a bull (the civic symbol of Acanthus), symbol of a fish below

Reverse: AKANΘION (of Acanthus), inscription surrounding a quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image from Wildwinds (Desneux 95 ff)

Jules Desneux (referenced below), in his catalogue of the coins of Acanthus, assigned the ‘tetradrachms’ in his database to one of three periods, with the transition from Period I (coin types 1-92) to Period II determined by the emergence of the new reverse design (see for example the example of his coin type 95, illustrated above). He dated this transition to ca. 480 BC (for the same reason that Raymond subsequently gave for the start of Alexander’s ‘signed octadrachms’ - see above).

As we have seen, John May, who was apparently convinced by Doris Raymond’s dating of the start of Alexander’s ‘signed’ coinage to 480 BC, concluded that:

“... the honour [of originating the the new reverse design] must rest with Alexander or, possibly, Acanthus ”

He suggested (at note 20) that:

“The introduction of this style of reverse at Abdera comes very little later than that at Acanthus, where Desneux [referenced below] suggested the date ca. 480 BC for its introduction, which seems from an overall consideration of the Acanthian coinage to be rather too early.”

He argued that:

✴the ‘very rough work’ of the reverses of Raymond’s Group I ‘mounted horseman octadrachms‘ Alexander] would not have inspired ‘an independent Hellenic mint like that of Acanthus to adopt this design; and

✴this honour should go to the more refined reverses of Raymond’s Group II ‘standing horseman octadrachms‘ Alexander, which are assigned ‘with a fair degree of probability’ to ca. 475/6 BC.

In short, on his model:

✴Alexander:

•introduced the new reverse type on his ‘signed mounted horseman octadrachms’ of ca. 480 BC; and

•refined the design for his ‘signed standing horseman octadrachms’ of ca. 476/5 BC;

✴followed in quick succession by:

•Acanthus, for Desneux’s ‘tetradrachm’ 93, the first to be signed AKANΘION;

•Abdera, for the ‘signed tetradrachms’ issued by Phittalos in the period 473/70 BC.

Likely Scenario for the Introduction of the New Reverse Design

More recently, Margarita Tačeva (referenced below, at p. 61) set out a more likely scenario, in which, after the defeat of the Persians at Eion in 476 BC:

“Abdera announced its newly-acquired political autonomy by the new reverse with the name of the magistrate, [Phittalos]. The coinage of Abdera, being well-attested and subject to periodisation through the coin magistrates, seems to me [to be] the only reliable way, at least for the time being, of establishing the relative chronology in the appearance of the reverse in question on [the coins of other Thraco-Macedonian issuers, including Alexander]. The ... new inscribed reverse ... probably originated ... in the two cities, Acanthus and Abdera, which had had [their own numismatic] traditions ... [for] decades.”

Note that she was not relying here on new hoard evidence (for which, see below) but rather on the balance of probabilities. However, she was aware that this more recent hoard evidence included the existence of the ‘new’ inscribed reverse design at other Thraco-Macedonian mints. In the light of this later evidence, she argued (at pp.61-2) that:

“... popularity and prestige [of the new reverses that Abdera and Acanthus, perhaps introduced in ca. 475 BC] was a sufficient condition for their successive acceptance by the Bisaltae, [and the kings] Getas, Alexander and Mosses.”

I discuss the new hoard evidence in the following section. For the moment, we should simply note that, even before we begin this analysis, there is a good case to be made in favour of the suggestions that:

✴(pace Raymond and May) all of Alexander’s ‘signed’ coinage was issued after ca. 475 BC; and

✴their reverse design was inspired by the ‘fashion’ that had been set at that time for the new ‘signed tetradrachms‘ of Abdera and Acanthus.

Hoard Evidence

In the sections that follow, I look at a series of hoards that are relevant to the coinage of:

✴Alexander;

✴the other contemporary coinage from the Thraco-Macedonian region; and

✴the civic coinage of Abdera and Acanthus.

I discuss these hoards in the order of their ‘discovery’, in order to demonstrate how much more evidence for these coinages has emerged since Desneux, Raymond and May published their pioneering work.

Tigris Hoard (IGCH 1762, 1816)

Alexandros Tzamalis, (referenced below, at pp. 324-8) summarised what is known about this hoard, which was apparently discovered on the banks of the Tigris, some 65 km south of Ctesiphon (in modern Iraq). The important thing for our purposes is that a small number of the coins that emerged at this time were sold to the British Museum.

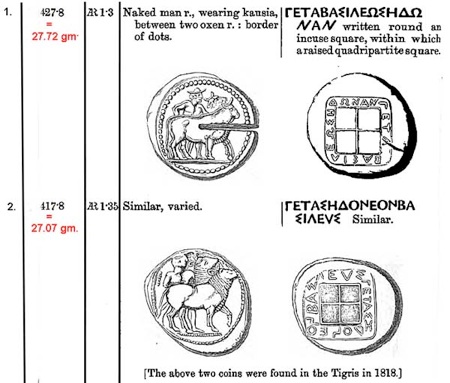

Getas, King of the Edones

Catalogue entry by Barclay Head (referenced below, 1879, at p. 144)

for the coins of Getas, King of the Edones in the British Museum

Tzamalis observed (at p. 327) observed that three ‘signed two oxen octadrachms’ of Getas in the collection of the British Museum came (or probably came from this hoard:

✴his coin 1 (29.25 gm., catalogued at p. 179 and illustrated on Plate 42) was ‘signed’ on the obverse, with a reverse of a four-spoked wheel in an incuse square: and

EΔΟΝΕΟΝ ΒAΣΙΛ[…] ΓΙΤΑ ΝΟΜΙ-ΣΜ-Α (nomisma = coin); and

✴two (illustrated above) were signed on the reverse:

•his coin 17 (27.07 gm., catalogued at pp. 187-8 and illustrated on Plate 43)

ΓΕΤΑΣ ΗΔΟΝΕΟΝ ΒΑΣΙΛΕVΣ; and

•his coin 18 (27.70 gm., catalogued at pp. 188-9 and illustrated on Plate 43)

ΓΕΤΑ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΗΔΩΝΑΝ.

As Tzamalis observed (at pp. 327-8) the uncertainties that surround this hoard (and, in particular, about whether or not it included coin 1) limit is value as a source of chronological evidence: claims made for its large size and varied composition mean that it could have covered the entire period of Getas’ coinage.

Zagazig Hoard (IGCH 1645, 1901)

This hoard was discovered on the site of ancient Bubastis (in the Nile delta some 70 km north of Cairo), which had fallen to the Persians in ca. 525 BC. Alexandros Tzamalis, (referenced below, at p. 338) noted that its date of closure has been variously placed at ca. 470 or ca. 450 BC.

Derrones

Types of ‘heavy’ silver coins of the Derrones in the Zagazig Hoard (described below)

Images: A from ANS 1944.100.11955 ; B from ANS 1944.100.11956

This hoard contained three coins of the Derrones, all of which were catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis:

✴two of these coins:

•his coin 15 (38.19 gm), catalogued at p. 38, illustrated at Plate 10:2 and at ANS 1944.100.11955 (coin A above); and

•his coin 21 (31.4 gm.), catalogued at p. 41 and illustrated at Plate 10:2;

each has:

•on the obverse: a man leading a pair of oxen that are drawing cart (a wheel of which is visible behind them); and

•on the reverse, a quadripartite incuse square; and

✴the third, his coin 57 (38.89 gm.), catalogued at p. 51 and illustrated at Plate 10:5 (type illustrated at ANS 1944.100.11956 - coin B above) has:

•on the obverse: a man driving a cart drawn by two oxen, with a Corinthian helmet over the ox; and

•on the reverse: the symbol of the triskeles with a flower between each pair of legs in an incuse square.

Acanthus

This hoard apparently contained five ‘tetradrachms’ of Acanthus, although Jules Desneux (referenced below) was aware of only three:

•coins 19 and 20, catalogued at p 58 and illustrated on Plate 6; and

•coin 28, catalogued at pp. 61-2 and illustrated on Plate 7.

All three had an anepigraphic quadripartite incuse square reverse.

Kabul Hoard (IGCH 1830; 1933)

As summarised in this (excellent) page from Wikipedia, this hoard:

“... was discovered by a construction team in 1933 when digging for foundations for a house near the Chaman-i Hazouri park in central Kabul. According to the then director of the Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan (DAFA), the hoard contained about 1,000 silver coins and some jewellery. 127 coins and pieces of jewellery were taken to the Kabul Museum and others made their way to various ... [museums and private collections]. Some two decades later, Daniel Schlumberger of DAFA published photographs and details of the finds stored in the Kabul Museum.”

Unfortunately, the Kabul Museum was looted in 1993, albeit that many of the stolen coins probably survive in private collections.

According to the Wikipedia page mentioned above, his coin list included:

✴64 Greek coins, all apparently from the 5th and 4th centuries BC (32 from Athens and 30 from other Greek cities);

✴a later Iranian imitation of an Athenian ‘owl’ tetradrachm;

✴9 royal Achaemenid silver coins (siglos); and

✴29 locally minted coins, together with 14 ‘punch-marked’ coins in the shape of bent bars.

(Unfortunately, these coins were looted from the museum in 1993, albeit that at least some of them subsequently re-emerged into private collections.)

Afghanistan seems to have been part of the Persian Empire since ca. 530 BC, and it is therefore unsurprising that this hoard had contained coins of the Achaemenid dynasty of Cyrus the Great. The imitation Athenian tetradrachm, which was judged to be the latest of the known coins in the hoard, was dated to ca. 380 BC, and this is usually accepted as the date at which the hoard was buried.

Acanthus

‘Signed’ tetradrachm (weight ?) of Acanthus from the Kabul Hoard (Desneux 97)

Obverse: Lion attacking a bull (the civic symbol of Acanthus), symbol of a fish below

Reverse: AKANΘION (of Acanthus), inscription surrounding a quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image from Wikipedia

Schlumberger’s list included two tetradrachms from Acanthus, both of which were catalogued by Jules Desneux (referenced below):

•his coin 45, catalogued at pp.71-2 and illustrated on Plate IX, which had an anepigraphic quadripartite incuse square revers; and

•his coin 97 (illustrated above), catalogued at p. 85.

Alexander I

‘Signed standing horseman octadrachm’ of Alexander (28.64 gm.), catalogued by

Doris Raymond (referenced below (coin 51a, at p. 101)

Obverse: horseman wearing chlamys (cloak) and petasus, carrying two spears, standing behind his horse;

hound leaping up in front of horse; head of caduceus brand on its rump

Reverse : ΑΛΕ/ΞΑ/ΝΔ/ΡΟ: Inscription surrounding quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image from Doris Raymond (referenced below, Plate VI)

Raymond also catalogued but did not illustrate a similar coin (25.13 gm., clipped) from the

Kabul Hoard as coin 52, at p. 101

Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 65, note 5) noted that:

“The two most recently-appearing Alexander octadrachms [are] from a hoard found in Afghanistan ...”

These coins did not appear in Schlumberger’s catalogue because they were already in private collections. She was unable to examine one of them, but she catalogued the other one (as coin 52, at p. 101). This was, in fact, the only ‘octadrachm’ in her catalogue that had been found in a hoard.

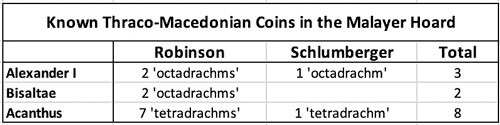

Malayer Hoard (IGCH 1790; 1934)

This hoard, which was discovered in northwestern Iran, remains essentially unpublished: Daniel Sclumberger and and Sir Edward Robinson (both referenced below) published lists of some of the coins that it had contained, and Colin Kraay and Peter Moorey (referenced below, 1968, at p. 232) reproduced their lists side-by-side, but there is no reason to believe that, between them, they contain every coin from the hoard. These authors argued that, based on these lists, the hoard closed at some time during 425-400 BC. The interesting aspect of these lists for our purposes is that, as set out in the table above, taken together, they suggest that the hoard had contained at least:

✴3 ‘octadrachms’ attributed to Alexander;

✴2 ‘octadrachms’ attributed to the Bisaltae; and

✴8 ‘tetrdrachms’ of Acanthus.

Alexander and/or the Bisaltae

Anepigraphic ‘standing horseman octadrachm’ (28.14 gm) from the Malayer Hoard,

now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (SNG Ashmolean, 2242)

Catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis, (referenced below, coin 127, at p. 111)

Obverse: standing horseman wearing a petasus, carrying two spears and standing behind his horse

Reverse: Quadripartite square, divided by two crossed lines

Image from Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, Plate 27)

As Alexandros Tzamalis, (referenced below, at p. 338) observed, we are hampered by the lack of published information about the five Thraco-Macedonian ‘octadrachms’ in the lists:

“We do not know, for example, of what type are the coins [attributed to] Alexander I, which might be anepigraphic ‘standing horseman octadrachms’]. On the other hand, one of the two Bisaltian coins [illustrated above], which I was able to find [in the Ashmolean Museum], is precisely of this anepigraphic type, which can [actually] be assigned to either Alexander or the Bisaltae”, (my translation).

In other words, we should rather conclude that this hoard contained at least five anepigraphic Thraco-Macedonian ‘octadrachms’, each of which can probably be attributed to either Alexander or the Bisaltae.

Acanthus

As noted above, this hoard apparently contained eight ‘tetradrachms’ of Acanthus. [More]

Massyaf Hoard (IGCH 1483; 1961)

Colin Kraay and Peter Moorey (referenced below, 1968, at pp. 210-20) published this hoard soon after its discovery at Massyaf in northwestern Syria. They noted (at p. 220) that it contained 75 attributable coins and concluded (at p. 222) that it had been buried in ca. 425/20 BC.

Bisaltae

This hoard contained a ‘signed standing horseman octadrachm’ of the Bisaltae (coin 4) which was also catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis, (referenced below) as coin 67, at p. 100. This coin was of the same type as coin 6 in the Jordan hoard (see below): these coins belong to Tzamalis’ Group A.3, which have a symbol of a bearded Silenus (either Silenus himself or a Silenus-like figure = old satyr) in front of the horse. Sallie Fried (in Ian Carradice (editor), rfeerenced below, at p. 2) observed that the type with this symbol:

“... seems to be the latest before the coins with the ethnic on the reverse are struck by the Bisaltae [(see the Black Sea Hoard below]),”

Acanthus

This hoard apparently contained a ‘tetradrachm’ of Acanthus (coin 3, Desneux 56-68). This puts them in Desneux’s Period I, which pre-dated the introduction of inscribed reverses at Acanthus.

Jordan Hoard (IGCH 1482; 1967)

Colin Kraay and Peter Moorey (referenced below, 1968, at pp. 181-210) published this hoard soon after its discovery on the Jordanian-Syrian border. It contained 113 coins, and Kraay and Moorey dated the latest of them to ca. 445 BC (at pp. 209-10). These coins included 13 Thraco-Macedonian coins, 4 of which were ‘octadrachms’.

Alexander I

‘Signed mounted horseman octadrachm’ from the Jordan Hoard (? gm.)

Obverse: mounted horseman wearing chlamys and petasus, carrying two spears

Reverse: ΑΛΕ/ΞΑ/ΝΔ/ΡΟ: inscription surrounding quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image from Colin Kraay, (referenced below., Plate 15, coin 2)

Kraay and Moorey (referenced below,1968, at p. 183) catalogued this as their coin 3 and placed it in Raymond’s Group I.

Bisaltae

‘Signed Octadrachm’ (28.51 gm.) of the Bisaltae, catalogued by

Alexandros Tazmalis (referenced below, coin 63, pp. 99-100)

Obverse: [CΙΣΑ] Γ T I KΩΝ: bare-chested horseman carrying two spears, standing behind horse;

symbol of a bearded Silenus in front of the horse (Tzamalis; Group A.3)

Reverse: Quadripartite incuse square

Image from Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, Plate 10:22, number 63)

A fragmentary coin (16.59 gm.) of this type (coin 65 - see below) was in the Jordan Hoard

Two other ‘octadrachms’ in the hoard were fragmentary ‘signed standing horseman octadrachms’ of the Bisaltae:

✴Coin 6 (6.2 gm.) was catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis, (referenced below, as coin 49, at p. 95). This coin was of the same type as fragmentary coin 4 in the Massyaf Hoard hoard (see above).

✴Coin 7 (16.59 gm.) was catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below), as coin 65, at p. 100). [Note: according to Tzamalis (at p. 322) the type of his coins 63-5 was also represented the Elmali Hoard - cross-reference below].

These coins were of the same type as coin 4 in the Massyaf hoard (above), They belong to Tzamalis’ Group A.3, which have a symbol of a bearded Silenus in front of the horse. As we have seen, Sallie Fried (in Ian Carradice (editor), referenced below, at p. 2) observed that the type with this symbol:

“... seems to be the latest before the coins with the ethnic on the reverse are struck by the Bisaltae [(see the Black Sea Hoard below]),”

Tyntenoi

‘Signed octadrachm’ of the Tyntenoi (29.83 gm.) from the Jordan Hoard, now in the Asmolean Museum, Oxford

Obverse: TVN: bare-chested, bearded man wearing a petasus, standing between two oxen

Reverse: Wheel with four spokes inside an incuse square

Image from Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, Plate 10:1, number1: Tynenton)

The fourth Thraco-Macedonian ‘octadrachm’ (29.83 gm.) in the hoard, which is illustrated above, was catalogued by:

✴Kraay and Moorey (as coin 10, at p. 183); and

✴Alexandros Tzamalis (as coin 1, at p. 179).

It is signed TVN on the obverse: this is usually taken to indicate a tribe known as the Tyntenoi, which is known only from the inscription TYNTENON on 2 smaller coins (ca. 9 gm) catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at p. 202-3) as coins 16 and 17.

The ‘octadrachm’ discussed here is the only known coin of this weight issued by this tribe (although it is possible that there was a second in the Elmali Hoard - see below). It is very similar to a small number ’signed’ by the equally obscure Ichnae (who were represented in the Asyut Hoard - see below).

Abdera and Acanthus

This hoard contained:

✴a fragmentary ‘tetradrachm’ from Abdera (coin 13, 10 gm.) = May 84; and

✴three tetradrachms from Acanthus:

•coin 3 (unknown weight) = Desneux 18;

•coin 4 (8.57 gm.) = Desneux 48-68; and

•coins 5 (7.27 gm.) = Desneux 80-81.

The ‘tetradrchm’ from Abdera (May’s Period III) and those from Acanthus (Desneaux’ Period I) all pre-dated the introduction of inscribed reverses to the coinage of northern Greece.

Asyut Hoard (IGCH 1644; 1968/9)

This hoard was discovered on the west bank of the Nile, some 300 km south of Cairo. Martin Price and Nancy Waggoner published it in 1975 (in a book, referenced below, that I have not been able to consult). In his review of this book, Colin Kraay (referenced below, at p. 189) observed that:

“... because of its size (nearly 900 coins) and the variety of its contents, [this hoard] prompts a thorough reassessment of our entire conception of archaic Greek coinage. Despite the hazards of chance discovery and dispersal, it proves to be not only the largest hoard of the period hitherto known, but [also], thanks to [work of Price and Waggoner], by far the most completely recorded. Its contents, [covered] the whole Greek world, including Sicily and south Italy ...” .

Kraay (as above) also noted that Price and Waggoner had listed the coins in the hoard:

“... with professional skill, and ... compared [this list] with those of other archaic hoards in order to determine the date of burial and the relative position of Asyut in the sequence of archaic Greek hoards. [They concluded] that the hoard came late in the sequence, and that its terminal date was ca. 475 BC.”

Derrones

This hoard contained 14 heavy coins of various weights (ca. 30-40 gm.) ‘signed’ by the Derrones, all of which Alexandros Tzamalis included in his ‘Emission I’. He divided these coins into two groups:

✴his Group A (coins 1, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 11, catalogued at pp.31-6) have obverses depicting an ox or a pair of oxen harnessed to a cart, the wheel of which is the only visible element: and

✴his Group B (coins 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 and 22, catalogued at pp. 36-41), which have similar obverses, except that a man now stands behind the ox/ oxen.

Tzamalis noted (at p 337) that these 14 coins coins represent a large proportion (61 %) of the 23 known coins of his ‘Emission I, all of which have anepigraphic quadripartite incuse square reverses.

Ichnae

‘Signed octadrachm’ (12.83 gm., clipped) of the Ichnae, from the Asyut Hoard

Catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below) as coin 1, p. 176, described below

Image from Tzamalis’ Plate 41

This hoard contained 5 ‘signed octadrachms’ of the Ichnae (Asyut 40-44) which:

✴Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015) catalogued (at p. 349 ) as coins 2 and 4-7; and

✴Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below) catalogued (at pp. 176-8) as his coins 1-4 and 6.

These coins all had the same iconography::

✴their obverses are ‘signed’ ΙΧΝΑΙΩΝ and depict a man wearing a petasus and standing between and controlling two oxen; and

✴their reverses depict a four-spoked wheel in an incuse square;

as in the ‘TVN’ coin in the Jordanian Hoard, discussed above. Tzamalis noted (at p 337) that these 5 coins represented a large proportion (62 %) of the 8 known coins of his group. Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 3520 observed that these five coins:

“... are from four obverse and four reverse dies, and all dies are done by the same hand; they show some wear, which supports the date of 490–480 BC given by Price and Waggoner [(referenced below)]”.

Orrescii

This hoard contained at least 35 ‘signed staters’ (ca. 9 gm.) of the Orrescii, which were all cataloged by Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at pp. 128-65). All of the ‘staters’ had obverses depicting a centaur seizing a maenad (nymph), and Tzamalis split them into four groups (A-D). He noted (at p 337) that these 35 coins included examples of all his groups:

“... which suggests that this entire issue was minted in a relatively short period shortly before the hoard was buried”, (my translation).

Acanthus and Abdera

This hoard contained:

✴37 ‘tetradrachms’ from Acanthus; and

✴10 ‘octadrachms’ and 2 ‘tetradrachms’ from Abdera.

Colin Kraay observed (at p. 192) observed that, if we put Alexander’s coin (see below) to one side:

“... as far as north Greece is concerned, the Asyut Hoard closed while the [anepigraphic] quadripartite incuse square was still the normal reverse type at most mints:

✴among the Derrones (above);

✴on the staters of the Orrescii (above); [and]

✴at Abdera and at Acanthus.”

Although I have been unable to consult the catalogue of Price and Waggoner, I have found two later references that allow us to date these coins of Abdera and Acanthus more precisely (at least in relative terms):

✴Colin Kraay and Peter Moorey (referenced below, 1981, at p. 3) observed that the latest ‘tetradrachm’ from Acanthus in the Asyut Hoard pre-dated Desneaux’ coin 49, which was issued in his Period I (coin types 1-92, ca. 530 - 480 BC); and

✴Martin Price (in Ian Carradice (editor), referenced below, at pp. 45) observed that the latest Abderite coins in the Asyut Hoard belonged to John May’s Period II (520/15 - 492 BC).

Alexander I

Silver ‘octadrachm’ (ANS 1970 225 1 , 27. 51 gm., clipped) from the Asyut Hoard (coin 152)

Obverse: horseman wearing chlamys and petasuss, carrying two spears and standing behind his horse:

waning moon behind his head

Reverse: ΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟ: Inscription surrounding quadripartite square within an incuse square

This hoard contained a ‘signed standing horseman octadrachm’ of Alexander (Asyut 152, ANS 1970 225 1, illustrated above). Colin Kraay (referenced below, at p. 190) observed that its presence in the hoard:

“... caused [Price and Waggoner] great embarrassment ... [because it] can only be accommodated before 475 BC (the postulated terminal date of the hoard) by the ruthless reversal of the sequence of Raymond's Groups I and II.”

The problem was that, as we have seen, Price and Waggoner had judged that the hoard had closed in ca. 475 BC; but

✴John May (referenced below, at p. 86, note 2), who accepted May’s assumption that Alexander’ ‘signed’ coinage had started in ca. 480, had argued that:

•the ‘very rough work’ of Raymond’s Group I reverses was unlikely to have inspired ‘an independent Hellenic mint’ like that of Abdera to adopt this design; but

•the more refined reverses of the ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ of her Group II, which (on her dating) began in ca. 476/5 BC, might well have dono so.;

✴Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 101) had already catalogued four of Alexander’s ‘signed standing horseman, waning moon octadrachms’ (numbered 53-7) as the last coins of her Group II (ca. 476 - 460 BC), suggesting that coins of this type dated to ca. 460 BC.

As we have seen, Colin Kraay (referenced below, at p. 192) had observed that:

“... as far as north Greece is concerned, the Asyut Hoard closed while the [anepigraphic] quadripartite incuse square was still the normal reverse type at most mints, ... [including that at] Abdera ...:

As we have seen::

✴the latest Abderite coin in the Asyut Hoard belonged to John May’s Period II (520/15 - 492 BC); while

✴the ‘new’ inscribed reverse had appeared at the time of Phittalos, at the start of May’s period IV, which he dated to 473/70 BC.

Colin Kraay (referenced below, at p. 192) argued that this development in reverse design cannot have occurred in:

“... less than decade, which will bring Alexander's ‘octadrachm no. 152 down the about 465-460, which is about where Raymond originally dated it.”

He therefore argued (at pp. 192-3) that Raymond’s date for Alexander’s ‘waning moon octadrachms’ should stand, and that, although the great majority of the coins in the hoard had probably arrived at Asyut before ca. 475 BC, a reduced flow could have continued for some time before the hoard was actually buried. By way of precedent, he observed that:

“Such a pattern has already been suggested by the Jordan Hoard [above], which was certainly not finally closed until after 450 BC, but which nevertheless contained rather few coins from mainland Greece that could be attributed to the [three decades prior to its closure].”

It seems that Martin Price subsequently accepted Kraay’s analysis: he acknowledged (in Ian Carradice (editor), referenced below, at p. 45) that:

“... as Dr. Kraay has shown, we must accept that the single [coin] of Alexander in the [Asyut] Hoard was an addition to the original deposit.”

The important point for our purposes is that John May (in 1966) and Colin Kraay (in 1977) had demonstrated the importance of the ‘new’ reverse that was introduced at most of the mints of northern Greece at about the same time (ca. 465 BC) in establishing the chronology of the coinage of this region.

Black Sea Hoard (CH 1:115, before 1970)

Colin Kraay and Peter Moorey (referenced below, 1981) published this hoard on the basis of a private collections that had been acquired for the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford in 1970. They deduced (at pp. 16-9) that the original hoard must have been buried in ca. 420 BC on the periphery of the Black Sea or the interior of Asia Minor.

Acanthus

‘Tetrdrachm’ (17.36 gm.) of Acanthus, Desneux 49, from Numisbids

Obverse: Lion attacking a bull

Reverse: Quadripart incuse square

The fragment from Acanthus discussed below was apparently of a similar type

This hoard contained a fragment of a ‘tetradrachm’ from Acanthus (coin 3, at p.3). Kraay and Moorey commented that:

“The exact obverse die appears not to be included in Desneux, ... [but] closest are [those following his coin 49, an example of which is illustrated above].”

The coin in the hoard would therefore have fallen into Desneaux’s Period I (coin types 1-92, ca. 530 - 480 BC). However, Kraay and Moorey argued that:

“On the evidence of the Asyut Hoard [(above)], from which these issues were absent, the date should be near 470 BC.”

Bisaltae

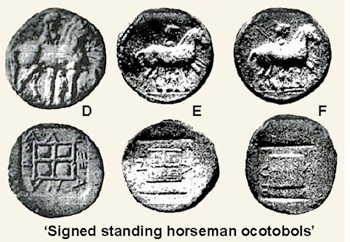

Obverses: Standing horseman wearing a petasus , carrying two spears , standing behind his horse

Reverse: ‘signatures’ surrounding a square divided by two crossed lines within an incuse square:

Inscriptions (all on the reverse):

A = ΑΛΕ/ΞΑ/ΝΔ/ΡΟ, catalogued by Doris Raymond, referenced below, as coin 46a (26.1 gm.) at p. 100

B = [ΒΙΣΑ]ΛΤΙΚ[Ο]Ν); from the Black Sea Hoard, now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford;

catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis, referenced below, as coin 133 (12.9 gm.), at p. 113

C = ΜΟΣΣΕΩ, cataloged in the Corpus Nummorum as CN type 4358 (29.32 gm.)

Image adapted from Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, Photo 2, at p. 382)

This hoard contained a fragmentary coin (number 2, at p. 2) that seems to have been part of a ‘signed standing horseman octadrachm’ (illustrated as B above). This would have been unremarkable, were it not for the facts that, if Kraay and Moorey correctly completed the fragmentary inscription ‘ΛΤΙΚ’ as [ΒΙΣΑ]ΛΤΙΚ[Ο]Ν), then this was (and still is) the only known ‘signed octadrachm’ of the Bisaltae on which the ‘signature’ is on the reverse. Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at p, 113) catalogued this coin (as a unicum) as his number 133. He:

✴tentatively agreed (at p. 381, note 122) with the attribution of this coin to the Bisaltae; and

✴commented (at note 123) that this attribution had subsequently been supported by the discovery of a very similar coin ‘signed’ by Mosses (illustrated above as C), which which appeared on the market in 2009.

Obverses: Standing horseman wearing a petasus , carrying two spears , standing behind his horse

Reverse:‘signatures’ surrounding a square divided by two crossed lines within an incuse square:

Inscriptions:

D = ΑΛΕ/ΞΑ/ΝΔ/ΡΟ, catalogued by Doris Raymond, referenced below, as coin 68b (4.02 gm.) at p. 103

E = ΒΙΣΑΛΤΙΚΟΝ, seen by Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 115, note 14) ‘at Naples’

F = ΜΟΣΣΕΩ, seen by Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 115, note 14) ‘in Brussels’

Coins of type F are also cataloged in the Corpus Nummoru as: CN type 4241 (3.98 gm.); and CN type 4356

(2 examples, average weight 3.18 gm.)

Images from Doris Raymond (referenced below: D=68b, Plate VII; E and F = ‘a and b’ at bottom of Plate VI)

Kraay and Moorey acknowledged (at p. 2) that a Bisaltian ‘octadrachm’ with the identifying legend on reverse would represent a new variety, but they justified their completion of the inscription by noting that this coin:

“... matches every detail certain rare octobols, of which only three examples appear to be known.”

They cited Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 115), who observed that the octobols E and F (see above), which she illustrated in her Plate VI:

“... have their obverses from the same die; one reverse has the Bisaltian ethnic, the other has the name of [the otherwise unknown] Mosses.”

She also observed (at note 2) that:

“Bisaltian octobols of this style are rather rare. I have been able to find:

✴the one illustrated [onPlate VI], from Naples;

✴another in Klagenfurt ... ; and

✴a third in Cambridge ... .”

She argued (at p. 123) that the issues of the octobols of the Bisaltae and Msoses roughly coincided with the issue of those of Alexander in her Group II, and that:

“The Bisaltian octobols and those of Mosses probably ceased with those of Alexander, since the need for that denomination had apparently never been very great in the north.”

Some authorities had initially questioned the authenticity of the obols of the Bisaltae (a possibility that Raymond had discounted in her note 2). This judgement was to some extent vindicated by:

✴the discovery of the Bisaltian ‘octadrachm’ in the Black Sea Hoard (coin B above); and

✴the subsequent emergence of the ‘octadrachm’ of Mosses (coin C above).

Note that Jonathan Kagan presented a paper entitled “Redating the Jordan Hoard, the Syrian [Massyaf ]Hoard and the Black Sea Hoard (IGCH 1482, 1483 and CH 1:115) with the Help of Lycian Coins” at the conference “New Hoard Evidence for the Chronology of the 5th century BC Athenian Coinage: 6th December 2022”) which is awaiting publication.

Elmali Hoard (CH 8:48, 1984)

Koray Konuk (referenced below, at p. 566) recorded that this spectacular coin hoard:

“... was found by treasure hunters using metal detectors n the village of Bayindir, near Elmali, one of the major settlements of northern Lycia, [which is now part of the Turkish province of Antalya]. Since no detailed inventory was made at the time of the discovery, we do not know the ... [original] number of the coins in the hoard. Most of [these] ca. 2,000 coins ... were smuggled [out of Turkey] after their discovery and [a group of American collectors] acquired ... ‘more than 1,700’ [of them. This] portion formed the basis of a conference held at Oxford in 1984. ... [These] coins were [finally] returned to Turkey in 1999 and ... a total of 1679 of them has been housed in the archeological museum of Antalya since 2009.”

This hoard is alternatively known as the ‘Decadrachm Hoard’ because it contained at least 13 Athenian ‘owl’ decadrachms (see, for example, the specimen illustrated by Koray Konuk, referenced below, figure 2, at p. 567). It is of particular importance because, as Koray Konuk (referenced below, at pp. 566-7) observed:

“What immediately struck those who saw [it] for the first time was the exceptional state of preservation of the coins. Most of them had not [or had hardly] circulated ... , [which means that they] had been [buried] soon after they were struck, most probably around 460 BC.”

Jonathan Kagan (in Ian Carradice (editor), referenced below, at p. 24) concluded that:

“... a closing date of 465/462 BC seems reasonable for the non-Lycian elements [in the hoard]”

As Koray Konuk (as above) observed, the book edited by Ian Carradice following the Oxford conference (referenced below) remains the most detailed study on the hoard to date. Importantly Sallie Fried provided a brief overview of the ‘more than 1,700’ coins that had been discussed at the conference (pp. 1-20). Furthermore the more recent catalogue in the published thesis of Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below):

✴contains a list of all the coins from the hoard that had been identified by 2011 (at p. 310); and

✴catalogued some of the Thracian coins in the main body of his work (where the hoard is designated as ‘Anatolie du Sud (Decadrachm), 1984’), although he noted (at p. 344, note 100), he had not had access to the coins in the Antalya Musuem, and had not, therefore, been able to include most of them in his catalogue.

Konuk himself presented a paper entitled “The Elmali, Lycia Hoard (CH VIII 48)” at the conference “New Hoard Evidence for the Chronology of the 5th century BC Athenian Coinage: 6th December 2022”) which is awaiting publication.

See also the relevant pages in the website ‘Homeland Antalya’

Ichnae (?)

Two effectively anepigraphic ‘two oxen octadrachms’ from the Elmali hoard, possibly 0f the Ichnae (described below)

Images from Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015,: Plate 1, coin 8; and Plate 2, coin 14

Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 350) catalogued these two coins and attributed them to the Ichnae:

✴coin 8 (28.70 gm.): apparently anepigraphic; and

✴coin 14 (28.24 gm.): ‘signed on obverse

Bisaltae

Bisaltian ‘signed standing horseman octadrachm’ from the Elmali Hoard (now in the Antalya Museum)

Obverse: ΒΙΣΑΛΤΙΚΟΝ: standing horseman wearing a petasus, carrying two spears and standing behind his horse

Reverse: Quadripartite square divided by two crossed lines

Image from Koray Konuk (referenced below, Figure 1, at p. 357)

The coin list of Sallie Fried (in Ian Carradice (editor) referenced below, at p. 9) included an astonishing 68 ‘signed standing horseman octadrachms’ of the Bisalte (one of which is illustrated above). She noted (at p. 1) that these coins had been:

“... struck from 26 obverse and ... 45 reverse dies, most of which were previously unknown.”

Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 358) observed that this signed coinage:

“... might have been issued over a few years, but it looks like a very compact series indeed: ... the pieces in the Elmali hoard are all very fresh and appear to have been minted more or less at the same time.”

Sallie Fried (as above, at pp. 1-2) observed, on these 68 coins:

“The reverse is always a simple four-part incuse square... , with the ethnic spelled out around the inside of the border [on the obverse].”

Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below) was able to catalogue six of them:

✴four of them belonged to his Group A.1 (no symbols):

•coin 12 (28.92 gm., at p. 85) = Sallie Fried (Plate 1; coin 1);

•coin 16 (28.56 gm., at p. 86) = Sallie Fried (Plate 1; coin 3);

•coin 31 (28.33 gm., at p. 90) = Catharine Lorber (referenced below, at Plate 14, coin B); and

•coin 46 (28.39 gm gm., at p. 94) = Sallie Fried (Plate 1; coin 2); and

✴two belonged to his Group A.2 (with the symbol of a Corinthian helmet in front of the horse):

•coin 61 (28.56 gm.(?), at p. 99) = Sallie Fried (Plate 1; coin 4); and

•coin 62 (weight ?), at p. 99) = Martin Price (in Ian Carradice (editor) referenced below, at p. 44, obverse illustrated at Plate VII, coin 1).

Sallie Fried (as above) observed (at p. 2) that:

✴there were seven coins with the helmet symbol in the hoard, all of which were from one obverse die; but

✴there were no coins the Silenus symbol in the hoard (although, as we have seen, this type was represented in both the Massyaf Hoard and the Jordan Hoard).

Abdera and Acanthus

According to the list of Sallie Fried (in Ian Carradice (editor) referenced below, at p. 9), the hoard included:

✴19 coins from Abdera:

•5 ‘octadrachms’ and a ‘tetradrachms’ from May’s Periods I-II; and

•13 tetradrachms’ from May’s Period III, the latest of which were issued at the time of a magistrate who ‘signed’ himself as ΤΕΛΕ (May type 83, p. 104); and

✴37 ‘tetradrachms’ of Acanthus, the latest of which are of Desneux’s type 90 (signed ‘A’ on the obverse, see p. 81).

All these coins had anepigraphic ‘quadripartite incuse square’ reverses, although the latest of the ‘tetradrachms’ of Acanthus was the next-to-last type there before the adoption of reverse inscriptions.

Getas, King of the Edones

‘Signed octadrachm’ (27.77 gm.) of Getas, king of the Edones, from the Elmali Hoard

Obverse: ΛΙΤ Α: man wearing a petasus, standing between two oxen, calf runs in front of the oxen

Reverse: four-spoke wheel within an incuse square

Image from Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, Plate 3, number 21)

The coin illustrated above seems to be the one that Sallie Fried (in Carradice (editor), referenced below) attributed to the ‘Tunteni’ (in her list at p. 9). However, Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 351, note 17) observed that:

“... it is actually a piece of Getas, which is clear from die-linked specimen in Berlin [illustrated at her Pl. 3, 22]”.

‘Signed octadrachm’ (28.57 gm.) of Getas, king of the Edones, from the Elmali Hoard (now in the Antalya Museum)

Obverse: man wearing a petasus, standing between two oxen

Reverse: ΓΕΤΑ ΒΑΣΙΛEΩΣ ΗΔΩΝΑΝ: Inscription surrounding a quadripartite square within an incuse square

Image from Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, Plate 10:43, number 20)

Sallie Fried (in Ian Carradice (editor), referenced below, at p. 2) recorded that the hoard contained three ‘signed two-oxen octadrachms’ of Getas, who styled himself on his coins as king of another Thracian tribe, the Edones:

✴one with the inscription ΓΕΤΑ ΒΑΣΙΛEΩΣ ΗΔΩΝΑΝ (illustrated above and catalogued by Alexandros Tzamalis, referenced below, at p. 189, coin 20); and

✴two with the inscription ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΣ ΓΕΤΑΣ ΗΔΟΝΕΟΝ, which were presumably of the same basic type (see, for example, the coin catalogued by Alexandros Tazamalis, referenced below, as coin 17, pp. 187-8, which has this inscription).

Sallie Fried (as above) observed that these coins:

“... are the only north Greek coins with reverse inscriptions in the hoard ... . The very fresh condition of these specimens and the presence of the reverse inscription place them among the latest from [northern Greece] in the [hoard].”

In other words, these three coins all probably date to ca. 460 BC.

Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2021, at p. 51) observed that most Thraco-Macedonian coinage pf this period is identified by the name of the tribe rather than that of its leader, and that:

“The most notable exception is the coinage of Getas, king of the Edones, whose name and title are indicated on coins in a variety of combinations on both obverses and reverses (Fig. 7). Since both the Elmalı and the ‘Karkemish’ hoards (unpublished - [see below]) contained such coins, which were absent in the Asyut hoard, it seems likely [that Getas’] reign may be dated to ca. 465–450/40 BC.”

Derrones

‘Signed’ coin (39.10 gm.) of the Derrones, from the Elmali Hoard

Obverse: ox pulling a cart driven by a bearded man holding a whip,

symbols of a branch and an eagle carrying a lizard above the ox

Reverse: triskeles made up of three male legs, within an incuse square

Image from Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, Plate 10:16, number 184)

As Alexandros Tzamilis (referenced below, at p. 311) observed, this is the only known example of a ‘heavy’ silver coin of the Derrones that has these two symbols together (although examples of a type with the ingle symbol of an eagle carrying a lizard are known from a hoard in Bulgaria). He placed this coin at the end of the coinage of the Derrones.

Karkemish Hoard (1994)

Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at p. 313) noted that the earliest indication of the existence of the Karkemish hoard came in 1991, when previously unrecorded coins of the Bisaltae began to appear on the market. These indications:

“... were quickly combined with waves of information which concerned a hoard from the border region between Syria and Turkey ... [that was] comparable in size to the [Elmali hoard] or even larger”, (my translation).

✴He estimated that the hoard had contained at least 2,000 coins, including:

•at least 72 of or attributed to the Bisaltae;

•at least 7 of the Edones; and

•at least 2 of the Orrescii; and

gave the closure date of the hoard as ca. 465-460 BC, although he also noted that the presence in this hoard of types of the coins of the Bistaltae that were not present in the Elmali Hoard suggests that it closed shortly after 465- 462 BC (see above).

✴Lisa Kallet and John Kroll (referenced below, at Appendix B, p. 156, number 44) gave a more conservative estimate: they recorded that it contained about 400 coins, including:

•9 ‘signed’ tristaters [= ‘0ctadrachms’] of the Bisaltae (all having ‘signed standing horseman’ obverses);

•30 anepigraphic ‘octadrachms’ attributed to the Bisaltae (presumably all having ‘standing horseman’ obverses); and

•5 ‘signed’ ‘octadrachms’ Alexander (with the ‘signature’ on the reverse - the obverses were type unrecorded); and

gave the closure date of the hoard as ca. 440 BC. They commented (at p. 10) that:

“... the scale of the Bisaltae coinage was greater than the [substantial] Elmali sample allows, as the Karkemish hoard of 1996 [sic] adds additional obverse dies from a continuation of the coinage after ca. 460 BC.”

Note that Ute Wartenberg presented a paper entitled “The Karkemish Hoard” at the conference “New Hoard Evidence for the Chronology of the 5th century BC Athenian Coinage: 6th December 2022”) which is awaiting publication.

Bisaltae

Four types of Bisaltian ‘octadrachms’ that were probably represented in the Karkemish Hoard (described below)

Images from Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at Plates 19, 22, 25 and 26 respectively)

Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below) catalogued four types of Bisaltian ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ that had probably been represented in the Karkemish (= his ‘Nord d'Aleppo’) Hoard:

✴two were signed on the obverse:

•coin 35, which belonged to his Group A.1 (no symbols), catalogued at p. 91; and

•coin 70, which belonged to his Group A.4 (symbol of a circle of globules), catalogued at p. 101; and

✴coins 93 and 114 from his anepigraphic Group B.1, catalogued at p. 106 and pp. 108-9 respectively.

As touched on above, Groups A.4 and B.I were not represented in the Elmali Hoard, which suggests that the Karkemish Hoard closed after 465- 462 BC.

Getas, King of the Edones

Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below) catalogued two ‘signed two oxen octadrachms’ of Getas that had probably been represented in the Karkemish Hoard, both of which (like the ‘Getas’ coins from the Elmali Hoard - see above) had the inscription surrounding a quadripartite square within an incuse square:

✴coin 16 (28.04 gm.), inscription ΓΕΤΑ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥ ΗΔΩ ΝΕΩΝ, catalogued at p,187; and

✴coin 19 (26.4 gm.), inscription ΓΕΤΑ Β ΑΣΙΛ[ΕΥ] ΗΔ ΩΝΑΝ, catalogued at p. 188.

Both are illustrated (alongside coins 17 and 20 mentioned above) on his Plate 10:43.

Jonathan Kagan (referenced below, 2014, at p. 4) observed that:

“The [Elmali Hoard] demonstrates that the beginning of inscriptions appearing around the incuse squares of coins of this region, [by which, I assume he meant those of Getas], dates to ca. 465 BC ‘’’”

Alexander I

As noted above, Lisa Kallet and John Kroll (referenced below, at Appendix B, p. 156, number 44) recorded that this hoard contained 5 ‘signed’ ‘octadrachms’ of Alexander, with the ‘signature’ on the reverse (presumably surrounding a quadripartite square within an incuse square), although they did not specify whether these had ‘standing horseman’ and/or ‘mounted horseman’ obverses.

Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 360) observed that:

“The extensive tristater [= ‘octadrachm’] coinage of Alexander I, minted in the 460s BC, presumably until his death, follows chronologically, it would seem, coinages such as those of the Bisaltae, Ichnai, and Orrescii. It is represented in large numbers in the 1994 Karkemish hoard.”

Combined Evidence from Asyut, Elmali and Karkemish

Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 350) observed that:

“At least two coins of Getas, probably more were recorded for the Karkemish 1994 hoard, and the Elmali hoard probably contained at least one such piece ... [Margarita Tačeva, referenced below, at pp. 623-4] argued (correctly in my view) that the Getas’ coinage was spread out over a longer period, from ca. 500–475/65 BC. What is clear from the hoards that contain larger coins is that there appear to be two periods of output for such denominations:

✴the first group (Derrones, Ichnai, Abdera, Getas) fall into the first two decades of the 5th century BC, perhaps even just during the last decade of the Persian Wars in ca. 490–480 BC.; whereas

✴the second group consists of a much larger number of mints, [which] include the later Abdera, Derrones, Ichnai, Tytenoi (?), Getas, Bisaltae, Orrescii and Alexander I. This is not the place to sort out the exact chronological issues of these various mints, but it is safe to say that they minted between 465 and 450 BC.

The two periods of issue were discussed by [Martin Price, in Ian Carradice (editor), referenced below, at pp. 44-5.] The main output, during which silver was coined into large denominations, falls into this later period.

Unallocated ‘Signed Hoard Octadrachms’ of Alexander

Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 355, note 32) observed that:

“There is no published die-study of the Alexander [‘octadrachms’], but the coins that appeared on the market as a result of the Karkemish and other hoards have illustrated that this is a very large series.”

I have not been able to establish whether these ‘unallocated ‘octadrachms’, many of which will have emerged from hoard including those of Elmali and Karkemis, were of both obverse types. However, Jonathan Kagan (referenced below, 2014, at p. 12 and note 28) referred to four examples of Alexander’s ‘octadrachms’ :

“... recently on the market (2000 and later) in Coin Archives gives a clearer picture. The four uncut specimens on that site weigh as follows:

✴[CNG Triton VII (11 January 2005), lot 135], 28.22 gm.;

✴[CNG Triton VIII (11 January 2005), lot 134], 28.56gm.;

✴[New York Sale XXVII (4 January 2012), lot 292], 28.73 gm.’ and

✴[CNG Triton VIII (11 January 2005), lot 132], 29.75 gm..”

All of these coins have ‘standing horseman] obverses.

Vranje Hoard

Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at p. 276) recorded that this hoard was discovered in Vranje (in southern Serbia) in 2003. It originally contained more than 100 coins of various weights (mostly in the range 30-40 gm.), all but one of which (see below) were signed by or attributed to the Derrones. There had been earlier interventions at the site, and the archeological context of the find was already compromised. Furthermore, the newly-discovered coins were quickly dispersed, although 24 of them were soon recovered and moved to the local museum.

Derrones

Silver coin (39.29 gm.) attributed to the Derrones, from the Vranje Hoard (now in the Vranje Museum)

Obverse: ox pulling a cart driven by a man holding a whip, shield symbol above the ox

Reverse: triskeles made up of three male legs, within an incuse square

Image from Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, Plate 10:15, number 167)

Tzamalis (at pp. 281-9) catalogued 90 of these Derronian coins:

✴the 24 in the museum; and

✴another 66 that had appeared on the market soon after 2003.

As we have seen, 15 heavy coins of the Derrones had been found in the Asyut Hoard, which had probably closed in ca. 475 BC. Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below) included 14 of them in his catalogue, all of which belonged to his ‘Emission 1’ (pp. 31-42):

✴6 in his ‘Group A’ (pp. 31-5), with the obverses depicting an ox harnessed to a cart; and

✴8 in his ‘Group B’ (pp. 36-42), with essentially the same design, but with the addition of a man standing behind the ox.

The reverses of all of these coins had only a plain quadripartite incuse square, while all of the coins at Vranje (including the example illustrated above) had:

✴a man driving an ox-drawn on the obverse ; and

✴the symbol known as the triskeles in an incuse square on the reverse.

Tzamalis argued that:

✴the absence of ‘triskeles’ at Asyut indicated that this hoard pre-dated that at Vranje(see p. 290): and

✴stylistic considerations suggested that all of the coins at Vrange had slightly pre-dated the 10 similar coins from the Velitchkovo Hoard (IGCH 690) in southern Bulgaria, which (in his opinion) had closed in ca. 470 BC (see p. 291 and pp. 305-7).

Alexander I

Silver Octadrachm (28.19 gm., from Doris Raymond, referenced below, Plate III, number 5; see also p. 78)

Obverse (mounted horseman wearing chlamys (cloak) and petasus, carrying two spears;

hound leaping up in front of horse; head of caduceus brand on its rump

Reverse : ΑΛΕ/ΞΑ/ΝΔ/ΡΟ: Inscription surrounding quadripartite square within an incuse square

The only other known coin of this type was in the Vranje Hoard and is now in the Vranje Museum (see below)

Tzamalis also catalogued the ‘outsider’ in the Vranje Hoard, which had also been retrieved soon after its discovery and moved to the museum (see his coin 91, at pp. 289-90): it weighed 33.54 gm and was an unusually heavy ‘signed’ mounted horseman octadrachm’ of Alexander. Tzamalis observed (at p. 290) that Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 78; illustrated above) had recorded the only other known coin of this type as her coin 5 (28.19 gm.), which she had assigned to her Group I (ca. 480 - 476 BC). He argued (at p. 290) that the presence of a coin of this type in the Vranje Hoard was one reason for reconsidering the dating of Raymond’s Group I:

“... because, since the ‘triskeles’ types of the Derrones were absent from the Asyut Hoard, they cannot be dated [before ca. 475 BC, when that hoard closed]”, (my translation).

The point here is that all 15 coins of the Derrones at Asyut had plain ‘tripartite incuse square’ reverses. In fact, even if we accept that the evidence from Asyut does indeed indicate that the the ‘triskeles’ types of the Derrones were not in circulation before ca. 475 BC, this ’fact’ alone would not necessarily undermine Raymond’s dating of the ‘signed mounted horse octadrachms’ of Alexander: after all, the single example found at Vranje could have arrived there before those of the Derrones, even if it was subsequently buried with or near them.

Read more:

Wartenberg U., “Thracian Identity and Coinage in the Archaic and Classical Period”, in

Peter U. and Stolba V. F. (editors), “Thrace: Local Coinage and Regional Identity”, (2021) Berlin, at pp. 45-64

Adak M. and Thonemann P., “Teos and Abdera: Two Cities in Peace and War”, (2020) Oxford

Kallet L. and Kroll J. H., “The Athenian Empire: Using Coins as Sources”, (2020) Cambridge Konuk K., “The Elmali Hoard’”, in:

Iscan H. and Dündai E. (editors), “From Lukka to Lycia: the Land of Sarpedon and St. Nicholas”, (2016) Istanbul, at pp. 566-p

Wartenberg U., “Thraco-Macedonian Bullion Coinage in the Fith Century BC: the Case of Ichnae”, in:

Wartenberg U. and Amandry M. (editors), “ΚΑΙΡΟΣ: Contributions to Numismatics in Honor of Basil Demetriadi”, (2015), New York, at pp. 347-64

Kagan J., “Notes on the Coinage of Mende”, American Journal of Numismatics, 26 (2014) 1-32

Tzamalis A. R., “Les Ethné de la Région ‘Thraco-Macédonienne’: Etude d’Histoire et de Numismatique (fin du VIe - Ve siècle)”, (2012) thesis of the University of Paris (Sorbonne).

Lorber C. C., “The Goats of’Aigai’”, in:

Hurter S. and Arnold-Biucchi C. (editors), “Pour Denyse: Divertissements Numismatiques”, (2000) Bern (at pp. 113–33)

Tatscheva, M., “ΓΕΤΑΣ ΗΔΟΝΕΟΝ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΣ”, in:

Peter U. (editor), “Stephanos Nomismatikos”, (1998) Berlin, at pp. 613-26

Carradice I, (editor), “Coinage and Administration in the Athenian and Persian Empires: Ninth Oxford Symposium on Coinage and Monetary History”, (1987) Oxford contains:

•Fried, S. “The Decadrachm Hoard: An Introduction”, at pp. 1-10;

•Kagan, J. H., “The Decadrachm Hoard: Chronology and Consequences”, at pp. 21-8; and

•Price M. J., “The Coinages of the Northern Aegean”, at pp. 43-7

Kraay C. M. and Moorey P. R. S, “A Black Sea Hoard of the Late Fifth Century BC”, Numismatic Chronicle, 141 (1981) 1-19

Kraay C. M., “The Asyut Hoard: Some Comments on Chronology”, Numismatic Chronicle. 17:137 (1977) 89-198

Price M. J. and Waggoner N., “, Archaic Greek Coinage: The Asyut Hoard” (1975) London

Kraay C. M. and Moorey P. R. S, “Two 5th Century Hoards from the Near East”, Revue Numismatique, 10 (1968) 181-235

Holloway R. R., “Review of ‘The Coinage of Abdera” by J, May, [referenced below]”, American Journal of Archeology, 71:3 (1967) 320-1

May J.M.F., “The Coinage of Abdera”, (1966) London

Schmidt E. F., “Persepolis II: Contents of the Treasury and Other Discoveries”, (1957) Chicago

Raymond D., “Macedonian Regal Coinage to 413 BC", (1953) New York

Schlumberger, D., “L’Argent Grec dans l’Empire Achéménide”, in:

Curiel R. and Schlumberger D. (editors), “Trésors Monétaires d’Afghanistan”, (1953) Paris, at pp. 5-64

Robinson E.S.G., “A ‘Silversmith’s Hoard’ from Mesopotamia”, Iraq 12:1 (1950) 44-51

Desneux J., “Les Tétradrachmes d'Akanthos”, (1949) Brussels

Head B. V., “British Museum Catalogue of Greek Coins, Macedonia, etc”, (1879) London