Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Alexander I: ‘Signed Octadrachms’:

Thraco-Macedonian Context (III)

Foreign Wars

Eastern Mediterranean (360 - 282 BC)

Alexander I: ‘Signed Octadrachms’:

Thraco-Macedonian Context (III)

In Construction

Thraco-Macedonian ‘Octadrachms’

In order to select the Thracian comparators that should be included in the analysis that follows, I have relied on the catalogue of Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below). The relevant coins for our purposes split into two groups:

✴24 with obverses depicting a young man who is wearing a petasus and leading two oxen (hereafter referred to as the ‘two oxen octadrachms’):

•9 ‘signed; by Getas, king of the Edones’ (catalogued at pp. 180-3):

•7 ‘signed’ by the Ichnae (at pp. 176-9); and

•8 ‘signed; by the Orrescii; and

✴a much larger number of coins that used variants of the ‘standing horseman’ obverse of Alexander (hereafter, together with those of Mosses and Alexander, referred to as the ‘signed standing horseman octadrachms’), including:

•78 ‘signed octadrachms’ of the Bisaltae (at pp. 82-102); and

•51 anepigrahpic ‘octadrachms’ (at pp. 104-113). (Note that Tzamalis’ coin 108, at p. 108, has the same weight as the anepigraphic coin illustrated above that ANS assigned to Alexander, which suggests that these are the same coin).

Much of what little we know about the relationships between the Macedonian kings and their neighbours (which would presumably have been reflected in their respective coinages) comes from a passage by Thucydides, who described an invasion of their territory by the Thracian King Sitalces in 429 BC, during the reign of Alexander’s son, Perdiccas II:

“Sitalces’ army was being mustered at Doberus and preparing to pass over the mountain crest and descend upon lower Macedonia, of which Perdiccas was ruler. For, the Macedonian race also includes the Lyncestians, Elimiotes and other tribes of the upper country, which, although in alliance with the nearer Macedonians and subject to them, have kings of their own; but the country by the sea which is now called [nearer] Macedonia, was first acquired and made their kingdom by Alexander , the father of Perdiccas, and by his forefathers, who were originally Temenidae from Argos. They defeated and expelled:

✴from Pieria, the Pierians, who afterwards took up their abode in Phagres and other places at the foot of Mount Pangaeus beyond the Strymon (and even to this day the district at the foot of Mount Pangaeus toward the sea is called the Pierian Valley); and

✴from the country called Bottia, the Bottiaeans, who now dwell on the borders of the Chalcidians.

They also acquired a narrow strip of Paeonia extending along the river Axius from the interior to Pella, [the future capitol of the Macedonian kings], and the sea; and beyond the Axius, they possess the district as far as the Strymon that is called Mygdonia, having driven out the Edones. Moreover, they expelled:

✴from the district now called Eordia, the Eordians, most of whom were destroyed, but a small portion is settled in the neighbourhood of Physca; and

✴from Almopia, the Almopians.

These Macedonians also conquered places belonging to the other tribes, which are still theirs: Anthemus, Crestonia, Bisaltia, and much of Macedonia proper. The whole is now calledMacedonia .. ...”, (‘History of the Peloponnesian War’, 2: 99: 1-6).

We can locate the territory of the Edones from a passage by Herodotus, in which he recorded that, in 480 BC, as the Persian King Xerxes marched westwards (see the map above), he:

“... marched past these Greek cities of the coast, keeping them on his left. The Thracian tribes through whose lands he journeyed ... [included the] Edones and the Satrae. ... [He then] passed the fortresses of the Pierians (one called Phagres and the other Pergamus) ... keeping on his right the great and high Pangaean range (where the Pierians and Odomanti and especially the Satrae have gold and silver mines). ... [Continuing] westwards , he came to the river Strymon and the city of Eion. ... [He crossed the Strymon] at Ἐννέα ὁδοὺς (Ennea Odoi, literally ‘Nine Ways’) in the country of the Edones by the bridges that they found thrown across [it]”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 110-3).

However, Getas , king of the Edones, is known only from the inscriptions on his coins, albeit that all of the coins ‘signed’ by the Edones also bear his name as their king.

Strabo recorded that:

“... the land on the far side of the Strymon ... is [that] of the Odomanti, the Edones and the Bisaltae (both those who are indigenous and those who crossed over from Macedonia), amongst whom Rhesus was king”, (‘Geography’ , 7: 36).

Pliny the Elder (‘Natural History’, 4: 111) places the Bisaltae on the west bank of the Strymon and both the Edones and the Odomanti to the east (as in the map above). We can reasonably assume that the Bisaltae and the Edones issued their coins from these locations. Although, as we have seen, the Odomanti are said to have owned gold and silver mines, they are not known to have produced any ‘signed’ coinage. Herodotus provided some information that might relate to the Ichnae when he recorded that:

“... the river Axius ... [marks] the boundary, between the Mygdonian and the Bottiaean territories, where narrow strip of land that belonged to the cities of Ichnae and Pella extends along the coast”, (‘Persian Wars’, 7: 123: 3).

However, as discussed below, there is some evidence to suggest that the Macedonians had driven them from the their settlement at Pella to another now-unknown location from which they issued at least some of their ‘octadrachms’. The Orrescii are known only from their coins.

There is also the question of where the issuers of these and other heavy silver coins obtained the required quantities of silver. Lisa Kallet and John Kroll (referenced below, at p. 78) observed that:

“Initially, the mines of this extensive area were worked by by local Thracian tribes, whose characteristically large and ostentatious silver coins ... attest to the great mineral wealth of the region.”

We can identify two of these mining areas from the records of Herodotus:

✴As we have seen, he recorded the presence of gold and silver mines in the Pangean mountains, near the territory of the Edones. Thucydides recorded that the mines of this area were also used by the inhabitants of the off-shore island of Thasus, who defected from the Athenian-led Delian League in 465 BC following:

“... disagreements about the markets and the mines that they possessed on the opposite coast of Thrace. The Athenians defeated them in a battle at sea and landed on the island. However, at about the same time, they had sent 10,000 settlers (some Athenians and others sent by their allies) to the Strymon river in order to found a colony in a place called then Ennea Odoi (now Amphipolis). They succeeded in taking the said Ennea Odoi, which was held by the Edones; but, when they advanced further into Thrace, they were defeated at Drabescus, a city of the Edones, by the whole power of the Thracians, who regarded the foundation of the colony at Ennea Odoi to be a hostile act”, (‘History of the Peloponnesian War’, 1: 100)

Peter Delev (referenced below, at p. 25) argued that:

“Wherever the battle actually took place, the main events of 465 BC seem to be [beyond] question: the Athenians had attempted a major advance into the Strymon area, and this was dramatically thwarted by the Edones, costing the life of most or all of the 10,000 Greek colonists. In a recent development of our knowledge [of the hoard evidence for the ‘octadrachm’ coinage of the Edones], it now seems possible to identify the king of the Edones who won this great battle: he would have been Getas, known from a series of heavy silver coins bearing different versions of the inscription ‘Getas, king of the Edones’.”

✴Herodotus also referred to:

“... that mine [near Lake Prasias, on the Strymon], from which Alexander later drew a daily revenue of a talent of silver: when a person has passed the mine, he need only cross the mountain called Dysorum to be in Macedonia”, (‘Persian Wars’, 5: 17: 2).

It is likely that the Bisaltae also made use of this mine.

If the Ichnae were settled in the vicinity of Macedonian Pella, then they too would presumably have relied on silver from mine near Lake Prasias. However, as I mentioned above, Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, see for example p. 353) established that they relied for a significant proportion of their coinage on the over-striking of the earlier ‘octadrachms’ of other authorities. (She also noted, p. 355, that an initial analysis of a small sample of the ‘octadrachms’ of other issuers revealed that this practice was also occasionally used for the ‘octadrachms’ of the Bisaltae and Alexander). She pointed out (again at p. 355) that one of the conclusions that emerges:

“... from this short survey of Thracian tristaters [= my ‘octadrachms’] is that a statistically significant number of bullion-style and other coins of Thrace were over-struck on older coins, and it appears that in particular Abdera’s [civic] tristaters were popular as host coins.”

(This page from the ANS database describes the five octadrachms of Abdera in the collection). It is possible that, when suitable ‘host coins’ were easily available, over-striking was preferred to the use of newly mine silver for coinage purposes:

✴because it offered economic advantages; or

✴because access to local mines was restricted or denied to specific issuers, as might have been the case, for example:

•when the Macedonians ‘made themselves masters’ of a number of local tribes, including the Bisaltae (see above); or

•if, as is possible, the Macedonians had driven the Ichnae from the vicinity of Pella to a now-unknown location at which the over-striking of silver coins from Abdera near the mouth of the Nestos river) was a particularly attractive proposition (discussed further below).

However, it is difficult to reach firm conclusions because, although recent advances have improved the dating of many of the relevant coins (as discussed in the following section), the dating of the recorded territorial gains of the Macedonians at the expense of their neighbours remains largely obscure.

Thracian ‘Two Oxen Octadrachms’

CN type 4366 CN type 4702 CN type 4388 CN type 4698

(see also CN type 4365) (see also CN type 4390)

ΙΧΝΑΙΩΝ ΝΟΜΙΣΜΑ ΕΔΟΝΕΩΝ ΟΡΡ(Η,Ε)ΣΚΙΩΝ ΓΕΤΑ ΒΑΣΙΣΙΛΕΥ

ΒΑΣΙΛΕΟΣ ΓΙΤΑ ΗΔΩΝΕΩΝ

28.97 gm. 29.07 gm. 28.23 gm. 28.18 gm.

As Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 351) observed, the broadly contemporary ‘octadrachms’ of the Ichnae, the Orresci and the Edones:

“... share the same obverse design of a young man with a broad-brimmed hat leading two oxen; [more specifically], he is restraining [the oxen] with an ornamental halter.”

The coins illustrated above (which come from the database of the Corpus Nummorum) depict four representative types of these coins, each of which is ‘signed’ on its obverse by the issuer. As we shall see, these ‘signed two oxen octadrachms’ have many similarities with the ‘signed standing horseman octadrachms’ of the Bisaltae:

✴they are made of the same metal (silver) and are of comparable weight (around 29 gm.);

✴their ‘signed; obverses depict a standing male figure who wears a petasus (and, in the case of the Orrreschi, carries two spears); and

✴ in two cases (the Orrescii and some of the Edones), they have the same reverse (depicting a quadripartite square divided by two crossed lines).

Ichnian ‘Two Oxen Octadrachms’

Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at pp. 349-50) catalogued 14 trisaters [= ‘octadrachms’] of the Ichnae, all of which had ‘wheel’ reverses and nine of which are securely signed on the obverse. She arranged them into two main groups (respectively Issues 1 and 2) on the basis of their detailed iconography:

✴Her Issue 1 contained six securely ‘signed’ coins of which:

•numbers 2, 4, 5 and 6 were discovered in the the Asyut Hoard (Asyut 40-43); and

•numbers 1 and 3 were of the same type as Asyut 43.

She observed (p. 352) that all four coins:

“... came from four obverse and four reverse dies, and the all dies had been done by the same hand; they show some wear, which supports the date of 490–480 BC [for the minting of these coins] ...”

✴Her Issues 2-3 contained another seven coins:

•three that were securely signed (numbers 11 -13, with her number 11= CN type 4366, illustrated above); and

•four coins (8, 9, 10 and 14) that were not securely ‘signed’, which she attributed to the Ichnae: two of them (8 and 14) came from the Elmali Hoard.

Following the general principle set out above, she dated the other coins to the period ca. 465-450 BC and noted (at p. 357) that:

“For the coinage of Ichnae, Issue II is represented by six specimens, minted from four obverse dies. ...[This suggests, on a conservative basis, that the [entire ?] issue of Ichnae was produced from over 54 Attic talents [of silver].

As we have seen, Herodotus recorded the existence of a town called Ichnae near the Macedonian town of Pella. Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 351) observed that there is archeological evidence for a settlement near Pella that might have been Herodotus’ ‘Ichnae’, although:

“Where the tristaters [= ‘octadrachms’] ... were made is a matter of some debate. Psoma and Zannis [referenced below, at pp. 39-44] have argued that the [‘octadrachms’ of the Ichnae] were actually minted much further to the east, between the Strymon and the Nestos rivers and not in [Herodotus’] polis of Ichnae, ... [probably because] the Ichnae had been expelled from their original settlement] by the Macedonians, just as various other people who had then settled further east.”

Selene Psoma and Angelos Zannis (referenced below, at p. 41) suggested that

“The date of the [Macedonians’] expulsion of Ichnae [from the vicinity of Pella] precedes that of their coinage, which dates from the first quarter of the 5th century BC. Like the Edones, who abandoned the Mygdonia region to settle between the Strymon and the Nestos and struck their coinage in this region, the Ichnae ... also settled somewhere between the Strymon and the Nestos and struck their coinage after their installation in this new land”, (my translation).

Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015 at p. 356), citing Psoma and Zannis, agreed that:

“... the Ichnae [had probably been] driven further north-east by the Macedonians, and the fact that [they] used coins of Abdera for [their] own coin production supports this argument.”

She had reported (at p. 353) that:

“... numbers 1, 2, 6, 10, 11, and 13 in the catalogue [of Ichnian ‘octadrachms’] show signs of over-striking on the reverse, although the exact under-type of these pieces is only certain in two cases (coins 1 and 11). ... The most noticeable over-stover-strike can be seen on coin 11, ... [and] it appears that this coin was over-struck on a tristater of Abdera.”

She now observed (at p. 356) that, although:

“... it is still not entirely clear how Abdera secured access to mines, ... the numismatic evidence suggests that Abdera is perhaps the most consistent and largest coin producer in the 6th and 5th centuries BC.”

I think that the argument here is that, in their new location, the Ichnae had sometimes found it attractive to re-use some of the prolific coinage of nearby Abdera than to rely o local mines (which were under the control of the Edones and of the Bisaltae and/or Alexander.

Orresciian ‘Two Oxen Octadrachms’

As Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at p. 359) observed:

“Only 18 [‘two oxen octadrachms’] with the legend of the Orrescii have been discovered to date, most of which come from old collections, without information from their origin having been preserved”, (my translation).

He catalogued these coins (numbered 1-18) at pp. 189-195, and pointed out (at p 360) that six of them (his 5, 7, 8, 12, 13 and 14) had appeared on the market between 1986 and 1991, while another had emerged in 1996. He suggested (see, for example, his Table 55, at p. 495) that these might well have come from the Elmali and Karkemish hoards (discussed above), in which case, they would have been issued in ca. 465-460 BC). Interestingly, unlike the ‘octadrachms’ of the Ichnae and those of Getas (see below) the young man standing between the oxen:

✴carries a spear in Tzamalis’ coin 1: and

✴ carries two spears (like the horseman on Alexander’s ‘octadrachms) in his numbers 2-18.

‘Two Oxen Octadrachms’ of Getas, King of the Edones

CN type 4702 CN type 4698 CN type 4703 CN type 4701

(see also CN type 4705) (see also CN type 4699)

on obverse: on obverse: on reverse: on reverse:

ΝΟΜΙΣΜΑ ΕΔΟΝΕΩΝ ΓΕΤΑ ΒΑΣΙΣΙΛΕΥ ΓΕΤΑ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΟΣ ΓΕΤΑΣ ΗΔΟΝΕΟΝ

ΒΑΣΙΛΕΟΣ ΓΙΤΑ ΗΔΩΝΕΩΝ ΕΔΩΝΑΝ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΣ

29.07 gm. 28.18 gm. 28.99 gm. 28.02 gm.

As we have seen, two types of Getas’ ‘octadrachms’ (CN type 4702 and CN type 4698, both illustrated above, to the left) have the inscription on their obverses. The other four have the inscription on their reverses (like the ‘standing horseman’ coins of Alexander discussed above):

✴in two of these (CN type 4703, illustrated above, and CN type 4705), the inscription surrounds a wheel with four spokes, all within incuse square; and

✴on the other two (CN type 4701, illustrated above, and CN type 4699). the inscription surrounds a quadripartite linear square, all within incuse square.

Peter Delev (referenced below, at p. 26) pointed out that:

“There were no ‘Getas’ coins in the Asyut hoard, closing around 475 BC (and, for that matter, [none] in all the coin hoards that can be dated with some certainty before Asyut). On the other hand, there were [at least] three ‘Getas’ coins in the later [Elmali hoard, discussed above], the closing date of the non-Lycian part of which is placed now around 465-2 BC. All three are reported in a “very fresh condition”, and all three belong to the later type of the coins of Getas, with the inscription on the reverse, around the four sides of a shallow, linear quadripartite incuse square.”

Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 353) pointed out that:

“At least two coins of Getas (and probably more) were recorded for the Karkemish 1994 hoard, and the Elmali hoard probably contained at least one such piece.”

In a later paper (Ute Wartenberg, referenced below, 2021, at p. 51), she observed that:

“Since both the Elmali and the ‘Karkemish’ hoards contained [‘signed’ coins of Getas, king of the Edones while the earlier Asyut hoard did not], it seems likely that [Getas’] reign may be [dated] to ca. 465–450/40 BC. It thus falls into a similar period to the main output of Alexander I of Macedon and of the Bisaltae [see below].”

As noted above, at the time at which Getas issued these coins, the Edones were settled near the gold and silver mines in the Pangean mountains and, in 465 BC, and become involved in what Peter Delev (referenced below, at p. 23) on a military campaign that Peter Delev argued:

“... might be considered to be the most noteworthy event in the known history of the Edones: the rout, in 465 BC of the 10,000 Athenian colonists who had [recently] settled at [nearby] Ennea Odoi.”

Whatever the uncertainties relating to the detail of these events, it is clear that the Edones and their Thracian and Thasian allies were spectacularly successful in preventing the Athenians gaining access to ‘their’ mines. In these circumstances, it is hard to escape the conclusion that Getas impressive issuance of ‘signed octadrachms’ celebrated his military success.

‘Two Oxen Octadrachms’: Conclusions

The ‘octadrachms’ discussed in this section clearly form a closely related group of heavy silver coins (or, to put it another way, of silver coins of an unusually high denomination). We know from the inscriptions of coins of this type that they were issued by the Ichnae, the Orrescii and the Edones. However, not all of the known types are ‘signed’ and, while these are usually assigned to either the Ichnae or the Edones, we cannot rule out the possibility that some or all of them were issued by other tribes in the region (for example, the Odomanti).

Stylistic analysis of the coins within the series suggests that the Ichnae led the way. The chronological context in which the style evolved has been estimated on the basis of the scant but potentially significant evidence of:

✴four quite heavily-worn ‘octadrachms’ that were ‘signed’ by the Ichnae in the Asyut Hoard, which is thought to have ‘closed’ in 475-470 BC; and

✴a small number of ‘signed octadrachms’ of the Orresciii and Getas, king of the Edones in the more poorly documented Elmali and Karkemish hoards, which seems to have closed about a decade later.

This suggest that all of these ‘octadrachms’ were issued over a short space of time (perhaps over some 2 decades from ca. 480 BC);

✴some of those of the Ichnae were issued before the end of the Persian War in 479 BC; but

✴the majority of the coins in this series were issued in the following decade.

These conclusions will need to be revisited in the light of the following analysis of the related ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ of the Bisaltae and others. However, even at this stage, it is possible to raise (albeit not to answer) a number of interesting questions:

✴some of these relate to the historical context in which the coins were issued: for example:

•why did the Ichnae, the Orrescii and the Edones issue such high value coins, and why only in this specific and relatively short period;

•why were some of them over-struck on earlier coins (often those that had originally been issued at Abdera) and

•what were the circumstances in which some of them soon found their way into treasure hoards in the Middle East; and

✴some of them relate to the ‘message’ on the coins themselves: for example:

•why did these three issuers choose essentially the same iconography for their coins;

•what lay behind their chosen motif of a young man wearing a petasus and leading two oxen; and

•did this iconography have the same meaning for all of them.

Thraco-Macedonian ‘Standing Horseman Octadrachms’

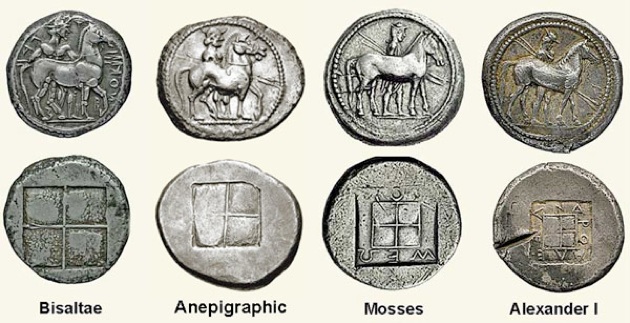

CN type 4203 Triton VIII, 2005 (lot 129) CN type 4358 ANS 1977 158 136

28.31 gm 28.78 gm. 29.32 gm 28.93 gm

The coins illustrated above represent the four main types of the Thraco-Macedonian ‘standing horseman octadrachms’, which I discuss, in turn, below.

‘Standing Horseman Octadrachms’ of the Bisaltae

‘Signed’ Bisaltian ‘Octadrachm’ from the Elmali Hoard (now in the Antalya Museum)

Obverse: ΒΙΣΑΛΤΙΚΟΝ: standing horseman wearing a petasus, carrying two spears and standing behind his horse

Reverse: Quadripartite square divided by two crossed lines

Image from Koray Konuk (referenced below, Figure 1, at p. 357)

Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at pp. 82-104) catalogued some 40 ‘octadrchms’ that were ‘signed’ on their obverses by the Bisaltae (with the inscriptions conveniently summarised in his Table 24, at p. 392). As Tzamalis further summarised (in his Table 22 at p. 304), these types all depicted the horseman bare-chested, with his torso seen from the front (as in the particularly fine example illustrated above).

No coins of this type were found in the Asyut hoard, and only two were found in the Jordan Hoard, one of which survived only as fragments: see, for example:

✴Colin Kraay and Peter Moorey (referenced below, 1968, at p. 182, numbers 6 and 7); and

✴Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, number 49, at p. 95 and number 65, at p. 100).

However, Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p 357-8) pointed out that:

“... with the discovery of the Elmali hoard, the [known ‘signed octadrachm’] coinage of the Bisaltae, which was previously known only from a few specimens, increased massively.”

Sallie Fried (referenced below, in Ian Carradice (editor), referenced below, at p. 1) recorded that this discovery added 68 specimens to the database, which were:

“... struck from 26 obverse and ... 45 reverse dies, most of which were previously unknown.”

Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p. 358) observed that this signed coinage:

“... might have been issued over a few years, but it looks like a very compact series indeed: ... the pieces in the Elmali hoard are all very fresh and appear to have been minted more or less at the same time.”

As noted above, this minting would have taken place shortly before ca. 460 BC, when the hoard was apparently buried. Lisa Kallet and John Kroll (referenced below, at p. 156) noted that another 9 coins of this series are thought to have been found in the Karkemish Hoard (along with 30 anepigraphic coins of the same general type, discussed below).

Lisa Kallet and John Kroll (referenced below, at pp. 77-8) observed that the coinage of the Bisaltae seems to have been by far the most abundant of the tribal coinages of this region. For example, Ute Wartenberg (referenced below, 2015, at p 357-8) estimated that in the the two decades to ca. 450 BC (when the production of Thraco-Macedonian ‘octadrachms’ ended):

✴the production of the ‘two oxen octadrachms’ of the Ichnae (above) required over 54 Attic talents of silver (p. 357); while

✴that of the ’standing horse octadrachms’ of the Bisaltae required over 191 Attic talents of silver (p. 358).

For the purposes of comparison, she estimated (at p. 358) that the Athenian ‘owl’ decadrachms (43.5 gm.), which were issued for a few years in the 460s BC and were represented in both the Elmali and Karkemish hoards (see Lisa Kallet and John Kroll , referenced below, at p. 17 and p. 156), were produced from just over 190 Attic talents of silver.

Colin Kraay and Peter Moorey (referenced below, 1981) published this hoard on the basis of a private collections that had been acquired for the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford in 1970. They deduced (at pp. 16-9) that the original hoard must have been buried in ca. 420 BC on the periphery of the Black Sea or the interior of Asia Minor. Only one (fragmentary) coin from this hoard is relevant for the present analysis: it seems to have been part of a ‘standing horseman octadrachm’. This would have been unremarkable, were it not for the facts that:

✴its reverse had an inscription that surrounded a square divided by two crossed lines within an incuse square; and

✴the authors read what remained of this inscription as ‘TIK’, which they completed as [ΒΙΣΑΛ]ΤΙΚ[Ο]Ν).

Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at p, 113 catalogued this coin (as a unicum) as his number 133. He tentatively agreed (at p. 381, note 122) with the attribution of this coin to the Bisaltae, and commented (at note 123) that this was supported by the subsequent discovery of a very similar coin ‘signed’ by Mosses (see below).

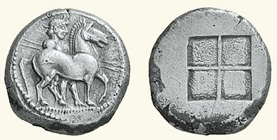

Anepigraphic ‘Standing Horseman Octadrachms’

A B

Anepigraphic ‘octadrachms’

Obverse: standing horseman wearing a petasus, carrying two spears and standing behind his horse

Reverse: Quadripartite square, divided by two crossed lines

✴A (28.78 gm.): image from (Triton VIII, 2005 (lot 129)

✴B (in which the horse’s rump is ‘branded’ with a kerykeon/ caduceus (27.29 gm.): image from Lisa Kallet and John Kroll (referenced below, Figure 4.6, at p. 79)

Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 53) described two types of ‘standing horseman octadrachms’:

✴one type that is ‘signed’ by the (Plate II, 1-3); and

✴one type that is anepigraphic.

She argued (at p. 55) that:

“In spite of the fact that the [standing horseman] type does not appear on Alexander's [‘signed’] octadrachms before Group II, the close association of [these anepigraphic] coins with those of Group I is self -evident ... That these coins are Macedonian rather than Bisaltian cannot be gainsaid ...”

She also argued (at p. 59) that Alexander struck these anepigraphic ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ in the period 492-480/79, in the period immediately preceding the introduction of his ‘signed mounted horseman octadrachms. However, as we shall see, Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below) has carried out a much more detailed analysis of the known anepigraphic ‘standing horseman octadrachms’, which is discussed below.

Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below, at pp. 104-113) catalogued 51 anepigraphic ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ (his coins 81-132), all of which shared the characteristic that both the head and the torso of the horseman were depicted in profile (as in the two examples illustrated above). Tzamalis did not assign any of these coins to the Karkemish Hoard because (as he rightly pointed out), the evidence in individual cases is circumstantial. Nevertheless, on the basis of an analysis of the pattern of emergence of coins of this type on the market, he concluded (at p. 314) that this hoard probably contained some 36 anepigraphic ‘standing horseman octadrachms’, a type that was apparently absent from the Elmali Hoard. More recently (as noted above), Lisa Kallet and John Kroll (referenced below, at p. 156) estimated that the Karkemish hoard had contained at least 30 anepigraphic coins of this type (along with at least 9 ‘signed’ by the Bisaltae).

It is usually assumed that:

✴the obverse designs of this anepigraphic type formed a stylistic ‘bridge’ between:

•the ‘bare-chested’ horseman seen from the front on the coins ‘signed’ by the Bisaltae; and

•the more refined figure seen from the side on those ‘signed’ by Mosses and Alexander (see below); and

✴this places them in between these two phases of ‘signed’ coinage in chronological terms (all three phases were apparently completed in quick succession.

As discussed further below, scholars are divided as to whether these coins of the intermediate phase constitute:

✴a late phase of Bisaltian coiange ;

✴an early phase of Alexander’s coinage (see for example, ANS 2002 18 8, which, as noted above, the ANS database assigns to Alexander); or

✴combination of the two.

However, the existence of the ‘Mosses octadrachm’ indicates that we cannot rule out the possibility that some of them were issued by other tribes in the region.

Alexandros Tzamalis (referenced below) catalogued three coins of this type (his coins 130-2, at p. 113) on which the rump of the horse is ‘branded’ with the symbol of a kerykeon (caduceus in Latin, a herald’s staff traditionally associated with the Greek Hermes and the Roman Mercury (see also coin B illustrated above). I will defer discussion of this motif at this point, since it also appears in the Alexander’s coinage, discussed below.

‘Standing Horseman Octadrachms’ ‘Signed’ by Mosses

CN type 4358: Tristater [= ‘octadrachm’], 29.32 gm.

Obverse: Standing horseman wearing a petasus , carrying two spears , standing behind his horse

Reverse: ΜΟΣΣΕΩ, surrounding a square divided by two crossed lines within an incuse square

Note that this database also includes two lower denomination coins of this type, complete with this inscription:

CN type 4241 (3,98 gm.); and CN type 4356 (2 examples, average weight 3.18 gm).

It seems from the only known ‘octadrachm’ signed by ‘Mosses’ (illustrated above, which appeared on the market in 2009) that the otherwise unknown issuer adapted the iconography of the anepigraphic ‘standing horseman octadrachms’ by:

✴refining the design of the obverse and clothing the horseman; and

✴adding the inscription ΜΟΣΣΕΩ around the quadripartite square on the reverse.

Since:

✴Alexander also adapted the same coins in this way; and

✴the Edonian king Getas applied the same reverse adaptation to both Ichnian and Orresciian reverses;

we can reasonably assume that Mosses was a king, although not necessarily of the Bisaltae. As Doris Raymond (referenced below, at p. 115, note 3):

“He may well have been one of those tribal chieftains mentioned by Thucydides (2: 99) who retained a measure of autonomy while paying tribute to Alexander.”

As we have seen, Selene Psoma (referenced below, in Table 1, at p. 175) suggested that Mosses’ ‘octadrachms’ (like those of Alexander) were issued between late 460s and the 450s BC.

Read more:

Adak M. and Thonemann P., “Teos and Abdera: Two Cities in Peace and War”, (2022) Oxford

Sprawski S., “The Temenidae, Who Came Out of Argos: Literary Sources and Numismatic Evidence on the Macedonian Dynastic Traditions”, Notae Numismaticae, 16 (2021) 13-42

Wartenberg U., “Thracian Identity and Coinage in the Archaic and Classical Period”, in

Peter U. and Stolba V. F. (editors), “Thrace: Local Coinage and Regional Identity”, (2021) Berlin, at pp. 45-64

Fantuzzi M., “The Rhesus Attributed to Euripides”, (2020) Cambridge and New York

Markowitz M., “Macedon Before Alexander”, CoinWeek Ancient Coin Series, 1t1h June (2020) 1-12

Fries A., “The Rhesus”, in:

Liapis V. and Patrides A. K. (editors), “Greek Tragedy After the Fifth Century: A Survey from ca. 400 BC to ca. AD 400”, (2019) Cambridge and New York, at pp. 65-88

Gerothanasis D., “The Early Coinage of Kapsa Reconsidered”, Proceedings of the XVth International Numismatic Congress at Taormina, 2015, (2017) Rome, at pp. 355-8

Konuk K., “The Elmali Hoard’”, in:

Iscan H. and Dündai E. (editors), “From Lukka to Lycia: the Land of Sarpedon and St. Nicholas”, (2016) Istanbul, at pp. 566-p

Psoma S. E., “Did the So-Called Thraco-Macedonian Standard Exist?”, in:

Wartenberg U. and Amandry M. (editors), “ΚΑΙΡΟΣ: Contributions to Numismatics in Honor of Basil Demetriadi” (2015) New York, at pp. 167-90

Knowles T., “Expansion, Bribery and an Unpublished Tetradrachm of Alexander I”, Journal of the Numismatic Association of Australia, 25 (2014) 16-24

Rusten J. and König J. (translators), “Philostratus: Heroicus; Gymnasticus; Discourses 1 and 2”, (2014) Cambridge MA

Sels N., “Ambiguity and Mythic Imagery in Homer: Rhesus' Lethal Nightmare”, The Classical World, 106:4 (2013) 555-70

Neils J., “The Dokimasia Painter at Morgantina”, in:

Schmidt S.and Stähli A.(editors) , “Vasenbilder im Kulturtransfer-Zirkulation und Rezeption Griechischer Keramik im Mittelmeerraum”, (2012) Munich, at pp. 85-92

Liapis V., “The Thracian Cult of Rhesus and the Heros Equitans”, Kernos, 24 (2011) 95-104

Vickers M., “Hagnon, Amphipolis and Rhesus”, in:

Sekunda N. (editor), “Ergasteria: Works Presented to John Ellis Jones on his 80th Birthday”, (2010) Gdańsk, at pp. 75-80

Delev P., “The Edonians”, Thracia, 17 (2007) 85-106

Liapis V., “Zeus, Rhesus, and the Mysteries”, Classical Quarterly, 57:2 (2007) 381-411

Kovacs D. (translator), “Euripides: Bacchae; Iphigenia at Aulis; Rhesus”, (2003) Cambridge MA

Lorber C. C., “The Goats of’Aigai’”, in:

Hurter S. and Arnold-Biucchi C. (editors), “Pour Denyse: Divertissements Numismatiques”, (2000) Bern (at pp. 113–33)

Gerber D. E. (translator), “Greek Iambic Poetry: From the 7th to the 5th Centuries BC”, (1999) Cambridge MA

Prestianni-Giallombardo A, M, and Tripoldi B, “Iconografia Monetale e Ideologia Reale Macedone: I Tipi del Cavaliere nella Monetazione di Alessandro I e di Filippo II” Revue des Éudes Anciennes, 98 (1996) 311-55

Strassler R., “The Landmark Thucydides: a Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War”, (1996) New York

Tatscheva M., “On the Problems of the Coinages of Alexander I, Sparadokos and the So-Called Thracian Macedonian Tribes”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 41:1 (1992) 58-74

Carradice I, (editor), “Coinage and Administration in the Athenian and Persian Empires: Ninth Oxford Symposium on Coinage and Monetary History”, (1987) Oxford contains:

•Fried, S. “The Decadrachm Hoard: An Introduction”, at pp. 1-10;

•Kagan, J. H., “The Decadrachm Hoard: Chronology and Consequences”, at pp. 21-8; and

•Price M. J., “The Coinages of the Northern Aegean”, at pp. 43-7

Kraay C. M. and Moorey P. R. S, “A Black Sea Hoard of the Late Fifth Century BC”, Numismatic Chronicle, 141 (1981) 1-19

Hammond N. G. L. and Griffith G. T., “A History of Macedonia: Vol. II (550-336 BC)”, (1979) Oxford

Price M. J., “The Coinage of Philip II”, Numismatic Chronicle, 19:139 (1979) 230-241

Kraay C. M., “The Asyut Hoard: Some Comments on Chronology”, Numismatic Chronicle. 17:137 (1977) 89-198

Le Rider G., “Le Monnayage ďArgent et ďOr de Philippe Frappé en Macédoine de 359 à 294”, (1977) Paris

Price M. J. and Waggoner N., “, Archaic Greek Coinage: The Asyut Hoard” (1975) London

Price M. J., “Coins of the Macedonians”, ( 1974) London

Kraay C. M. and Moorey P. R. S, “Two 5th Century Hoards from the Near East”, Revue Numismatique, 10 (1968) 181-235

May J.M.F., “The Coinage of Abdera”, (1966) London

Schmidt E. F., “Persepolis II: Contents of the Treasury and Other Discoveries”, (1957) Chicago

Raymond D., “Macedonian Regal Coinage to 413 BC", (1953) New York

Schlumberger, D., “L’Argent Grec dans l’Empire Achéménide”, in:

Curiel R. and Schlumberger D. (editors), “Trésors Monétaires d’Afghanistan”, (1953) Paris, at pp. 5-64

Robinson E.S.G., “A ‘Silversmith’s Hoard’ from Mesopotamia”, Iraq 12:1 (1950) 44-51

Desneux J., “Les Tétradrachmes d'Akanthos”, (1949) Brussels

Smith C. F. (translator), “Thucydides: History of the Peloponnesian War, Vol. I, Books 1-2”, (1919) Cambridge MA

Svoronos J.N., “L’Hellénisme Primitif de la Macédoine Prouvé par la Numismatique

et l’Or du Pangee”, (1919) Paris