Foreign Wars (3rd century BC)

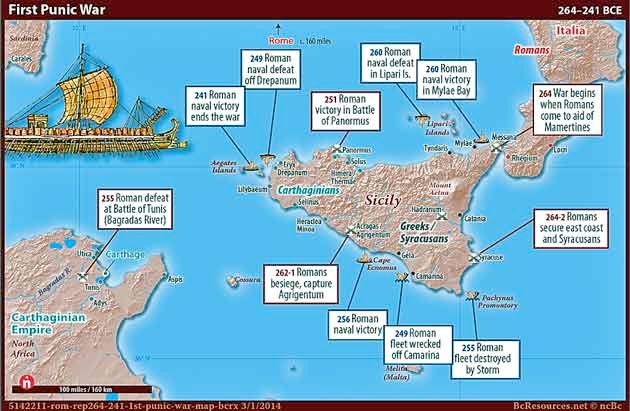

First Punic War (264 - 241 BC)

II: From the Fall of Agrigentum (262 BC)

to the Final Victory over the Carthaginians (241 BC)

Foreign Wars (3rd century BC)

First Punic War (264 - 241 BC)

II: From the Fall of Agrigentum (262 BC)

to the Final Victory over the Carthaginians (241 BC)

Western Mediterranean in 264 BC (adapted from this page in Wikipedia)

In Construction

Course of the War with Carthage

Battles of the First Punic War (from the website of BC Resources)

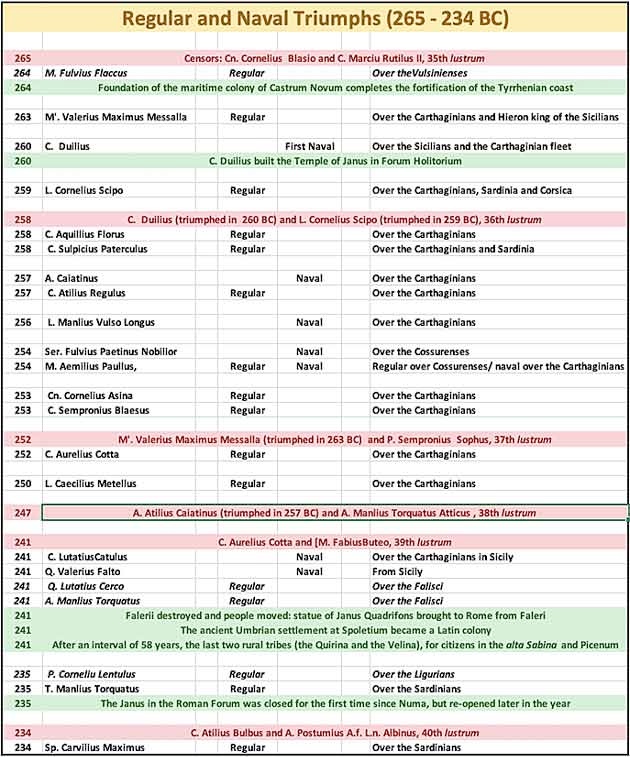

Triumphs from the fasti Triumphales; Censorships from the fasti Capitolini

Italics = triumphs won outside the theatre of war (Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica and, in 254 BC, the coast of Africa):

(i.e., those won at Volsinii in 264 BC and at Falerii in 241 BC)

One of the most useful sources for the progress of this long war is the Augustan list of triumphs known as the fasti Triumphales: as John Rich (referenced below, at p. 205) observed:

“From 264 BC and the start of Rome’s overseas wars, the triumphal list, [which is complete for the period of the war], can be accepted as both accurate and comprehensive. No valid grounds have been advanced for questioning the authenticity of any triumph listed in the extant inscribed lists for this period. Two triumphs not included in the Capitoline list are reported by some sources, but in each case they must be in error: these may be taken as instances of the false triumphs of family tradition, and it is reassuring that the inscribed list was not contaminated by them. The first of these is the triumph over the Carthaginians and king Hiero of Syracuse attributed by Eutropius, Silius Italicus and (by implication) Suetonius to Ap. Claudius Caudex, who as consul in 264 opened the First Punic War: the triumph may well have been mentioned by Livy (Eutropius’ usual source in this period), but, since there is no reference to it either in the inscribed list or in Polybius, Diodorus or Zonaras, our main sources for Claudius’ campaign, we can be sure that it was not held.”

Thus, as is evident to the list of triumphs in the table above and discussed below, M’ Valerius Maximus, in 263 BC celebrated the first of 21 triumphs that were awarding during the war and its immediate aftermath.

John Rich (referenced below, at p. 218) observed that 15 of the 16 triumphs celebrated between 264 BC (when he Romans crossed into Sicily) and 241 BC (when the Carthaginians accepted defeat and withdrew for Sicily, had involved victories over the Carthaginians (either alone or with allies):

✴the first of these 15 was celebrated by M. Valerius Maximus in 263 BC; and

✴the next, which C. Duilius celebrated in 260 BC, was the characterised in the fasti as ‘the first naval triumph, over the Sicilians and the Carthaginian fleet’.

I will discuss the events of these two years separately below. The sections that follow will then deal with

✴the period 259 - 25o BC, which witnessed 9 regular and 4 naval triumphs;

✴the period from the Romans’ disastrous defeat at Drepana in 249 BC until 242 BC, in which no triumphs were won; and

✴the final battles of the war in 241 BC, which led to two more naval triumphs.

Adapted from Map of the Roman Conquest of Italy (Wikimedia)

W

Province of Sicily

Polybius characterised the First Punic War as:

“... the war between the Romans and Carthaginians for the possession of Sicily ...”, (‘Histories’, 1: 63: 4).

Most of the military engagements during the war had taken place on or around the island and, as Simon Day (referenced below, at p. 1) observed, when it ended:

“Rome was left nominally in possession of the [western parts of the Sicily] that had previously been Carthaginian-controlled, namely the parts that were outside of King Hieron II’s Syracusan kingdom. The end of the war marked the beginning of Roman territorial overseas empire.”

Sicily had been the assigned province of at least one but usually two of the serving consuls throughout the war, but these assignments had been entirely military in nature. However, once hegemony over the western part of the island passed to the Romans, arrangements had to be made for its governance.

Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 88) observed that:

“... it would be surprising if Sicily did not receive a regular Roman magistrate ... [from] 241 BC [or soon thereafter in order] ... to protect and maintain this hard-won possession.”

However, the Romans had never before had control of am off-shore territory: as Cicero observed in a speech that he gave in 70 BC during his prosecution of C. Verres, the recently-returned governor of Sicily, this island:

“... was the first of all to receive the title of [permanent] province, the first such jewel in our imperial crown”, (‘Against Verres’, 2: 2: 2, translated by Leonard Greenwood, referenced below, at p. 297).

Corey Brennan (as above) pointed out that:

“A provincia certainly requires a magistrate (or pro-magistrate) to fill it, ... [and] the declaration of Sicily as a [permanent] provincia after the First Punic War should be synonymous with the sending of a magistrate.”

A surviving summary of Appian’s now-lost account of these events recorded that, when the western part of the island came under Roman control in 241 BC, the Romans:

“... levied tribute on the Sicilians, apportioned certain naval charges among their towns, and sent a praetor each year to govern them. (On the other hand Hiero, the ruler of Syracuse, who had cooperated with them in this war, was declared to be their friend and ally)”, (‘Wars on the Islands’, 3).

Brennan suggested (at p. 89) that this magistrate was the praetor mentioned by Appian, and that was one of the two annually-elected praetors, now known as praetor inter peregrinus. He pointed out that the role of this praetor would not have been primarily military, particularly since the Carthaginians were engaged in many urgent problems elsewhere (see below). He argued that:

“The most likely scenario is that the praetor in Sicily commanded a small fleet and perhaps a few cohorts of socii, acting in concert with the ... quaestor [based at Lilybaeum]:

✴to protect the coastal parts of the provincia from pirates; and

✴to see to the collection of taxes from those in the ex-Punic part of Sicily who were liable to them.”

Aftermath of the First Punic War

Roman Appropriation of Sardinia and Corsica (238 BC)

As we have seen, the treaty that the Romans imposed on the Carthaginians at the end of the war was extremely punitive: John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. ??) estimated that the imposed monetary payments amounted to over 80 tonnes of silver. The Carthaginians consequently found themselves unable to pay the mercenaries who had served with their army during the war, with the result that these mercenaries duly mutinied and marched on Carthage. This precipitated a revolt (the so-called Mercenary War) that drew in a number of the Carthaginian’s erstwhile African allies.

The treaty that had ended the war had not required any changes to the Carthaginian’s position in relation to either Sardinia or Corsica. HHowever, as the Carthaginians finally began to regain control over the rebels in Africa in 238 BC, others on Sardinia offered the island to Rome. Polybius recorded that, despite their treaty obligations:

“The Romans, ... on the invitation of the mercenaries who had deserted to them from Sardinia, undertook an expedition to that island. When the Carthaginians objected on the ground that the sovereignty of Sardinia was rather their own than Rome's, and began preparations for punishing those who were the cause of its revolt, the Romans made this the pretext of declaring war on them, alleging that the preparations were not against Sardinia, but against themselves. The Carthaginians, who had barely escaped destruction in the last war, were in every respect ill-fitted at this moment to resume hostilities with Rome. Yielding therefore to circumstances, they not only gave up Sardinia, but also agreed to pay a further sum of 1,200 talents to the Romans to avoid going to war for the present”, (‘Histories’, 1: 88: 8-12)

According to Eve Macdonald (referenced below, at p. 59):

“The Romans justified their actions by arguing that Sardinia lay in close proximity to the Italian coast, which meant that the island could be used for any future attack on Rome. It seems that, in the Roman view, the hostilities between the two states were far from over. To the Carthaginians, the Roman seizure of Sardinia was a great betrayal, a humiliation, and a cynical move at a time of great hardship.”

Polybius made no mention of Corsica, but there is evidence that the Romans considered it as a Carthaginian possession at this time: thus, according to Zonaras, during the war, the consul of 259 BC, Lucius Cornelius Scipio had:

“... made a campaign against Sardinia and against Corsica. These islands are situated in the Tyrrhenian sea and lie so near together that from a distance they seem to be one”, (‘Epitome of Cassius Dio’, 8:11).

Livy was explicit about the involvement of the Carthaginians in these engagements:

“Consul L. Cornelius Scipio fought successfully in Sardinia and Corsica against the Sardinians, Corsicans and the Carthaginian commander Hanno”, (Periochae, 20).

Since the Romans clearly laid claim to Corsica by 231 BC, when the Fasti Triumphales record that the consul C. Papirius Maso celebrated a triumph over the Corsicans on the Alban Mount, scholars usually assume that this claim dated back to the settlement with Carthage of 238 BC.

The Romans gained no immediate benefit from the expulsion of the Carthaginians from Sardinia and Corsica: as Gareth Sampson (referenced below, at p. 25) observed:

“... removing Carthage’s claims ... was one thing, but actually securing the territory was another. ... Carthage may have stepped aside without a fight , the Sicilians may have capitulated without much struggle, but the same cannot be said of the native inhabitants of Sardinia and Corsica, who were determined to resist any outside rule.”

As we shall see below, the Romans spent much of the 230s BC on the pacification of the Sardinians and the Corsicans, together with their Ligurian allies. (Meanwhile, the Carthaginians embarked upon another potentially threatening undertaking: the conquest of Hispania.)

Read more:

Macdonald E., “Hannibal: A Hellenistic Life”, (2018) New Haven and London

Day S., “The People's Rôle in Allocating Provincial Commands in the Middle Roman Republic”, Journal of Roman Studies, 107 (2017), 1-26

Brennan T. C., “The Praetorship in the Roman Republic: Volume 1: Origins to 122 BC”, (2000) Oxford

Sampson G., “Rome Spreads Her Wings: Territorial Expansion Between the Punic Wars”, (2016) Barnsley

Rich J., “The Triumph in the Roman Republic: Frequency, Fluctuation and Policy”, in:

Lange C. J. and Vervaet F. (editors), “The Roman Republican Triumph: Beyond the Spectacle”, (2014 ) Rome, at pp. 197-258

Lazenby J. F., “Hannibal's War: A Military History of the Second Punic War”, (1978) Warminster

Greenwood L. H. G. (translator), “Cicero: the Verrine Orations, Vol. I: Against Caecilius’ Against Verres, Part 1; Part 2, Books 1-2”, (1928), Cambridge, MA