Foreign Wars (3rd century BC)

First Punic War (264 - 241 BC)

I: From theLanding at Messana (264 BC)

to the Fall of Agrigentum (262 BC)

Foreign Wars (3rd century BC)

First Punic War (264 - 241 BC)

I: From theLanding at Messana (264 BC)

to the Fall of Agrigentum (262 BC)

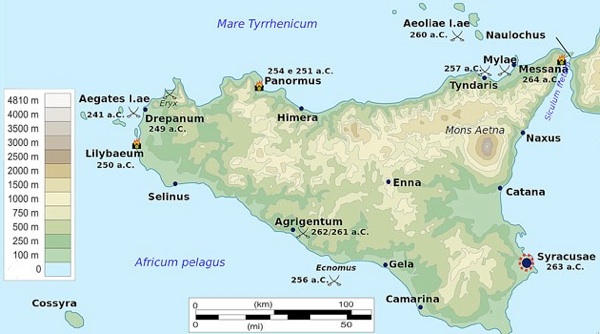

Sicily during the First Punic War(adapted from this page in Wikipedia)

War with King Hiero II of Syracuse (264-3 BC)

The Romans first became involved in Sicily in 264 BC, at some time after King Hiero II of Syracuse marched against a band of Campanian mercenaries known as the Mamertines, who had seized control of the strategically important city of Messana (only a short distance from Rhegium, on the Italian peninsular). According to Polybius:

“Observing that the Mamertines, owing to their [recent success in their engagements with him], were behaving in a bold and reckless manner, [Hiero] efficiently armed and trained the urban levies and leading them out engaged the enemy in the Mylaean plain near the river Longanus. [On this occasion, he] inflicted a severe defeat on them, in which he captured their leaders. This put an end to the audacity of the Mamertines and, on his return to Syracuse, he was with one voice proclaimed king by all the allies [of western Sicily]”, (‘Histories’, 1: 9: 7-8).

(See below for the alternative dating of the battle on the Longanus and the allies’ proclamation of Hiero as king to 269 BC.)

According to Polybius, in response to this setback:

“Some of [the surviving Mamertines] appealed to the Carthaginians, [who controlled the cities of eastern Sicily], proposing to put themselves and the citadel into their hands, while others sent an embassy to Rome, offering to surrender the city and begging for assistance as a kindred people”, (‘Histories’, 1: 10: 1-2).

The precise sequence of the events that followed is difficult to construct, mainly because of inconsistencies among our surviving sources. According to Nathan Rosenstein (referenced below, at pp. 88-9), the most likely scenario is that:

“[Hiero] followed up his victory on the Longanius] by laying siege to Messana. ... [However], the [Mamertines’] appeal to Carthage quickly bore fruit: a [Carthaginian] fleet happened to be anchored at the island of Lipara and, when its commander learned of the Mamertines’ defeat, he brought his garrison into Messana, forcing Hiero to abandon his siege.”

If this is correct, then the Mamertines had effectively given the Carthaginians control of Messana, thereby providing them with a base from which they could potentially take Syracuse and thus the whole of Sicily.

Appius Claudius Caudex (264 BC)

Meanwhile, in Rome, the senators were split on whether to answer the Mamertines’ plea for help against Hiero and, according to Nathan Rosenstein (referenced below, at p. 92), they:

“... possibly for the only time in memory, they allowed the consuls, [Ap. Claudius Caudex and M. Fulvius Flaccus], to bring the question of aiding the Mamertines before the assembly without any recommendation from the Senate ...”

Whatever the precise chain of events in Rome, Polybius duly noted that he assembly was:

“... in favour of sending help: when the measure had been passed by the people, they [gave] the command to one of the consuls, Ap. Claudius, who was ordered to cross to Messana”, (‘Histories’, 1: 11: 2-3).

(If the other consul, M. Fulvius, had indeed participated in these debates, he soon after left Rome to deal with what the surviving sources refer to as a ‘slave revolt’ at the Etruscan city of Volsinii.)

Claudius presumably left Rome imagining that his task was simply to lift Hiero’s siege of Messana and to facilitate the Mamertine’s return to the city (which would then, presumably, become a protectorate of Rome). However, it seems that the Mamertines’ managed to persuade the Carthaginians to leave the city and that, when they became aware of the Romans’ decision to send an army to Messana, they formed an alliance with Hiero in an attempt to capture Messana before Claudius arrived. Thus, as Nathan Rosenstein (referenced below, at p. 93) observed:

“When Claudius arrived at Rhegium [opposite Messana, he found a very different set of circumstances]: Messana was now threatened by ... two armies, one of which belonged to Rome’s old allies, Carthaginians.”

Since the Carthaginian navy controlled the strait of Messana, Claudius first sent a representative to open negotiations with Hiero and Hanno, the Carthaginian commander. Again, the surviving sources are inconsistent, but it seems that, although Hanno returned the Roman ships that he had already captured, he made it clear that Claudius himself should not attempt the crossing from Rhegium: according to Cassius Dio, Hanno:

“... declared that he would never allow the Romans even to wash their hands in the sea”, (‘Roman History’, 11: 43: 9).

He would certainly have been in a position to make such a threat, since Claudius would not have been able to take on the might of a Carthaginian naval force. However, according to the military strategist Frontiinus:

“ When Ap. Claudius, consul in the first Punic War, was unable to transport his soldiers from the neighbourhood of Regium to Messina because the Carthaginians were guarding the Straits, he caused the rumour to be spread that he could not continue a war which had been undertaken without the endorsement of the [Roman] people and ... pretended to set sail for Italy. Then, when the Carthaginians dispersed, believing he had gone, [Claudius] turned back and landed in Sicily”, (‘Stratagems’, 1: 4: 11).

It seems that the ruse worked because Claudius apparently managed to land his army near Messana. According to Polybius, he initially:

“... tried to negotiate with [Hanno and Hiero], ... but ,when neither paid any attention to him, he decided to risk an engagement ...

✴[First, he decided] to attack the Syracusans ... After a prolonged struggle, [he] was victorious and drove the whole hostile force back to their camp. After despoiling the dead, he returned to his camp. Hiero, [realising that he was beaten], retreated in haste after nightfall to Syracuse.

✴On the following day, ... [he mounted a dawn attack on the Carthaginians. In the battle that followed, his army] killed many of them and compelled the rest to retreat in disorder to neighbouring cities.

Having raised the siege by these successes, he [ensured his control of the surrounding territory and began the siege of [the famously impregnable city of] Syracuse]”, (‘Histories’, 1: 12: 1-4).

Claudius’ Achievement

Polybius noted that, when he had decided to discover how the Romans had secured the hegemony over nearly all of the inhabited world in less than 53 years (see 1: 1: 5), he had judged:

“... the Roman’s first crossing from Italy [to Sicily] with an armed force ... to be the most natural starting-point of this whole work”, (‘Histories’, 1: 16: 4-6).

Using the benefit of hindsight, this crossing had indeed marked the start of a new phase in Roman history: when Claudius’ crossed the Straits of Messana under arms in 264 BC, he:

✴defied the superior naval power of the (admittedly unprepared) Carthaginians, and

✴led the Romans into war against a Hellenistic king for the first (and by no means the last) time.

Furthermore, as Nathan Rosenstein (referenced below, at p. 94) pointed out, although circumstances had brought the Romans into conflict with the Carthaginians for the first time, Hiero II and eastern Sicily remained their over-riding concern.

M’ Otacilius Crassus and M’ Valerius Maximus (263 BC)

According to Polybius:

“When news of Claudius’ successes reached Rome, M’ Otacilius and M’ Valerius were elected as consuls and both of them, along the entire Roman army, were dispatched to Sicily”, (‘Histories’, 1: 16: 1-2).

Frank Walbank (referenced below, at p. 68) observed that:

“The sending of a double consular army, ... together with the allies, was exceptional, and a sign of the gravity of the occasion.”

We should stop at this point to consider why it was that Otacilius and Valerius apparently managed to cross the straits of Messana with their armies without any obvious difficulty. Pliny the Elder thought he had at least part of the answer:

“It is astonishing that, ... in the First Punic War:

✴the fleet of the commander Duillius [see below] set sail from the cutting down of the trees; [and]

✴[L. Calpurnius Piso Frugi, who was writing shortly after 146 BC] records that, against King Hiero, 220 ships were constructed in 45 days”, (‘Natural History’, 19: 74, translated by Mark Pobjoy, in Timothy Cornell (editor), referenced below, at Vol. 2, p. 325).

However, Polybius was famously dismissive of the Roman’s naval capabilities at this time:

✴he explained that the Romans subsequently formed an alliance with Hiero (see below) because:

“... since the Carthaginians commanded the sea and the armies that had previously crossed to Sicily had [consequently] run very short of provisions, they feared that, [without Hiero’s support], they might [similarly] be cut off on all sides from the necessities of life.”, (‘Histories’, 1: 16: 7); and

✴in surveying the military situation in 216 BC, after the Romans’ alliance with Hiero had been achieved and their military position elsewhere in Sicily had improved, he observed that, although they were content with their land forces, but:

“... Carthaginians maintained without any trouble the command of the sea and the fortunes of the war therefore continued to hang in the balance. ... [For this reason], they took urgent steps to get on the sea like the Carthaginians ... [and] undertook, for the first time, to build ships (100 quinqueremes and 20 triremes. As their shipwrights were absolutely inexperienced in building quinqueremes, such ships never having been in use in Italy, the matter caused them much difficulty ...”, (‘Histories’, 1: 20: 3-10).

Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at p. 355) suggested that Polybius had over-estimated the Carthaginians’ naval power and (at p, 360) that he had misrepresented the chronology of Rome’s first naval mobilisation of the war, arguing that:

“... dating [it] to 264/3 BC squares with logic and other historical data. The Roman leadership of 264 BC ... [must has realised that] they might have to reckon with enemy naval forces ... [and might well] have set about organising a fleet of any and all the warships owned by the Italian allies, as well as commissioning the rapid construction of others.”

Having said that, he argued (at p. 361) that:

“... Piso’s figures of 45 days and 220 ships cannot be accepted. Whatever the history of Roman naval policy before 264 BC, it is hard to imagine that Rome could have launched such a large fleet against Syracuse at such short notice”

It seems to me that:

✴Polybius also failed to appreciate that Claudius’ problems in 264 BC had probably arisen because he had been unaware of the presence of a Carthaginian fleet at Lipari; and

✴given the poor state of our surviving sources, there is no basis for doubting that, once forewarned of what lay ahead, the Romans would have been able to transport their land forces to Sicily in 263 BC before the Carthaginians and/ or the Syracusans could assemble the resources need to stop them.

However, that does not mean that the crossing was completely unopposed: as Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at p. 354), for example, argued that, since Valerius acquired the agnomen ‘Messala’ in this year [see below], he:

“... must have found Messana under siege or assault, [despite Claudius’ apparent success there in the previous year], and succeeded in liberating it permanently.”

The grammarian Charisius preserved the following fragment of the epic poem ‘Punica’ by Naevius (who had fought in the war):

“Marcus Valerius consul partem exerciti in expeditionem ducit (Marcus [sic] Valerius, the consul, leads a part of his army on an expedition”.

As Terence Hayes (referenced below, at p. 92, note 108) observed, this passage indicates that the consuls operated separately on some occasions during the year. However, according to Diodorus Siculus, they acted together immediately after their arrival when they marched south along the eastern coast and:

“... laying siege to the city of Hadranum, took it by storm. Then, while they were besieging the city of Centuripa ... , envoys arrived, first from the people of Halaesa and then, as fear fell upon the other cities as well, they too sent ambassadors to treat for peace and to deliver their cities to the Romans. These cities numbered 67. The Romans, after adding the forces of these cities to their own, advanced upon Syracuse, intending to besiege Hiero”, (‘Library of History’, 23: 4).

Agreement Reached by the Romans and King Hiero

The Romans must have realised that, by deciding to expand the ‘Sicilian mission’ beyond the protection of Messana and to go as far as laying siege to Syracuse, they had,in effect, declared war on Carthage for the control of the rest of the island. Hiero, for his part, must have concluded that he now had to choose between the Romans (who were on his doorstep, so to speak) and the Carthaginians (who would be unlikely to leave matters as they stood). Thus, the stage was set for another first: the Romans’ first treaty with a Hellenistic king.

According to Polybius, under the terms of this treaty:

“... the king agreed:

✴to give up his Roman prisoners to the Romans without ransom; and

✴to pay the Romans 100 talents; and

the Romans agreed to treat the Syracusans as friends and allies. King Hiero, having [thus] placed himself under the protection of the Romans, continued to furnish them with the resources of which they stood in urgent need, and ruled over Syracuse henceforth in security ... ”, (‘Histories’, 1: 16: 4-6).

Diodorus Siculus provided further detail on the terms of this agreement:

“Hiero, perceiving the discontent of the Syracusans, sent envoys to the consuls to discuss a settlement, and, since the Romans were eager to have as their foe the Carthaginians alone, they readily consented. [The parties therefore] concluded a 15-year peace [agreement, under which];

✴the Romans received 150,000 drachmas [and the return of Hiero’s roman prisoners]; and

✴Hiero was to continue as ruler of the Syracusans and of the cities subject to him, Acrae, Leontini, Megara, Helorum, Neetum, and Tauromenium.

While these things were taking place, Hannibal, [the Carthaginian commander] arrived with a naval force at Xiphonia, intending to bring aid to the king, but when he learned what had been done, he departed”, (‘Library of History’, 23: 4).

Cassius Dio, as epitomised by Zonaras) recorded that, in 248 BC:

“... the Romans had concluded a perpetual friendship with Hiero, and they furthermore remitted all the tribute that they were accustomed to receive from him annually”, (‘Roman History’, 12: Zonaras 8: 16).

This seems to support Diodorus’ assertion that the treaty of 263 BC had a term of 15 years.

Hiero II of Syracuse

Gold dekadrachm (60 litra) minted at Syracuse

Obverse: Head of Kore/ Persephone wearing a wreath made up of ears of corn, cornucopiae behind

Reverse: ΙΕΡΩΝΟΣ (Hieron): Nike (Victory) driving a biga

Only two of our surviving sources provide details of Hiero’s career before the First Punic War:

✴According to Pompeius Trogus, as epitomised by Justinus:

“When [King Pyrrhus of Epirus] had withdrawn from Sicily [in 275 BC], Hieron was made governor of it [sic]; and such was the prudence he displayed in his office that, by the unanimous consent of all the cities, he was first made dux adversus Carthaginienses (commander against the Carthaginians) and soon after king. ... He was the son or Hierocles, a man of high rank, whose descent was traced from Gelon [I], an ancient prince of Sicily ... [and] a female slave ... When he was a young man beginning his first campaign, an eagle settled on his shield and an owl upon his spear; ... and king Pyrrhus presented with many military gifts. ... He was affable in his address, just in his dealings, moderate in command, so that nothing kingly seemed wanting to him but a kingdom”, (‘Epitome of Pompeius Trogus' Philippic Histories’, 23: 4).

✴According to Pausanas, after Agathocles (who was tyrant of Syracuse from ca. 317 BC and self-styled basileus (king) from ca. 306 BC) died in 289 BC:

“... tyranny again sprang up [there] in the person of this Hiero [II], who came to power in the 2nd year of the 126th Olympiad [275 BC] ... This Hiero made an alliance with Pyrrhus, the son of Aeacides, sealing it by the marriage of his son, Gelon [later Gelon II] and Nereis the daughter [or, perhaps grand daughter] of Pyrrhus”, ‘Description of Greece’, 6: 12: 2-3).

These accounts are usually taken to indicate that, in the power vacuum that had been created when Pyrrhus left Sicily in 275 BC, Hiero had followed Agathocles’ example by proclaiming himself king of Syracuse. However, as we have seen, Polybius believed that it was only on his return to Syracuse after his defeat of the Mamertines that:

“... he was with one voice proclaimed king by all the allies [of western Sicily]”, (‘Histories’, 1: 9: 8).

Just to complicate things further, Polybius recorded that Hiero:

“... acquired the sovereignty of Syracuse and her allies by his own merit ... And, what is more, he made himself king of Syracuse unaided, without killing, exiling, or injuring a single citizen, which indeed is the most remarkable thing ... [Thereafter] during a reign of 54 years, he kept his country at peace:, (‘Histories’, : 8: 1-4),

Since Hiero died in 215 BC, this implies that he became king in 269 BC. Fortunately for our purposes, he was certainly recognised as King Hiero II of Syracuse by the time that Claudius crossed into Italy in 264 BC.

our purposes, the important point is that he had been proclaimed king by the time of Claudius’ arrival on Sicily. Efrem Zambon (referenced below, at p. 190) suggested that Hiero had minted the beautiful coin illustrated above was still στραταγός (stratagos, or overall commander of of a group of Sicilian cities, and that the presence of Nike on the reverse referred to his victories over the Mamertines in 270–269 BC.

Silver coin (32 litra) from Syracuse (Fig. 107, Syracuse: the Collaborative Numismatics Project)

Obverse: head of Hiero II, wearing a diadem

Reverse: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΟΣ ΙΕΡΩΝΟΣ (of Basileos/ King Hieron): Nike (Victory) driving a quadriga

For our purposes, the important point is that, by the time of Claudius’ arrival on Sicily, Hiero II regarded himself as a Hellenistic king and thus a western counterpart of Ptolemy II Philadelphus of Egypt and Antigonus II Gonatas of Macedon. As Andrew Wilson referenced below, at p. 88) observed, Hiero:

“... was no petty, small-minded Sicilian tyrant: [he] deployed the central geographic position of his independent Sicilian kingdom to the maximum advantage, and saw himself as a major player on the ancient world’s global stage. Not only does his coinage [see below] depict him in the manner of a Hellensitic king ... His great ship, the ‘Syrakosia’, built in ca. 240 BC and intended to make a great propaganda tour of the Hellenistic world, ... was given away as a present to Ptolemy [II] at Alexandria when Hiero realised that its designer, Archimedes, got one thing wrong: it was too big for most Mediterranean ports of its day.”

(See Emmanuel Nantet, referenced below, for the sources on this famous incident.)

set out in the webpage Syracuse: the Collaborative Numismatics Project (search on ‘Hieron II’), which characterised Hiero as basileus (labelled Class B)belonged to a series that also included coins with busts of:

✴his wife, characterised as basilissa (queen) Philistis (class D); and

✴their son, Gelon, wearing a royal diadem (class C);

all of which depicted Nike (Victory) driving a quadriga. As Carmen Arnold-Biucchi (referenced below) observed, these coins are probably coined at the same time and:

“Gelon appears with the royal diadem on his portrait coins, which therefore must have been issued after his father made him co-regent to the throne in 241/40BC ... Other elements point to a date after 240 B.C., in particular the iconography of Philistis’ portrait. It is in the best Hellenistic tradition and would fit very well with Seleucid or Ptolemaic representations of queens.”

According to Cassius Dio:

“After reaching an agreement with [Hiero, the consuls] turned their attention to the remaining cities garrisoned by the Carthaginians. However, they were repulsed from all of them except Segesta, which they took without resistance. [The reason for this was that] its inhabitants ... claim that they are descended from Aeneas. They [therefore] killed the Carthaginians [who were garrisoned there] and joined the Roman alliance”, (‘Roman History’, 11: 11).

Three passages in our surviving sources probably throw light on other events of this year:

✴Although our surviving sources make no explicit mention of Otacilius’ activity in Sicily, the military strategist Frontinus noted that:

“The consul Otacilius Crassus ordered those who had returned, having been sent under the yoke by Hannibal to camp outside the entrenchments,so that they might become used to dangers [in undefended locations] and so grow more daring against the enemy”, (‘Stratagems’, 4: 1: 19).

The dating of this event is unclear, since:

•M’ Otacillus Crassus was consul in both 263 and 246 BC and T. Ocilus (who was probably his brother) was consul in 261 BC; and

•a number of Carthaginian commanders called Hannibal served in this war.

However, most scholars (see for example, Andrew Smith, 2022, in entry 263/12 in this page in the Attalus website on Hannibal in Ancient Sources) assume that Frontinus referred to an occasion in 263 BC when M’ Otacillus Crassus apparently punished some troops who had been captured and sent under the yoke by the commander named Hannibal who subsequently was killed by his own troops in 258 BC.

If the scenarios suggested here are accepted, then this might well account for the fact that Valerius was awarded a triumph but both:

✴Claudius (who had not completely liberated the Mamertines); and

✴Otacilius (who had suffered what might have been a serious defeat at the has of the Carthaginians);

were not.

Commemoration in Rome of Valerius’ Victories in Sicily

According to Pliny the Elder:

“ ... Varro says that the first sun-dial that was erected for the use of the public [at Rome] was fixed on a column near the Rostra in the time of the First Punic war by the consul M. [sic] Valerius Messala, and that it was brought from the capture of Catina, in Sicily: this being 30 years after the date assigned to the dial of [L. Papirius Cursor after his triumph over the Samnites in 293 BC]. The lines in [Valerius’] dial did not exactly agree with the hours”, (‘Natural History’, 7: 60).

Leonhard Schmitz (in an article entitled ‘Horologium’ that William Smith included in his ‘Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities’ of 1875) explained that this solarium did not show the correct time at Rome because it had been made for a different latitude. Penelope Davies (referenced below, at p. 61) com observed that, following Papirius’ sundial and the sensational spoils that M'. Curius Dentatus had displayed during his triumph of 275 BC over the Samnites and King Pyrrhus had inspired:

“... a taste for sensationalism that [soon] infused other triumphs.”

She cited the 2,000 statues that had apparently featured in the triumph of M. Fulvius Flaccus in 264 BC and noted that:

“A year later, M’ Valerius Maximus Messall seized a sundial from Catania in Sicily, a wonder of a different kind: famed for marking the hous, it probably represented the cutting edge of scientific technology in the Greek world.”

Pliny also recorded that, in his opinion:

“... the high estimation in which painting came to be held at Rome, was principally due to M. [sic.] Valerius Maximus Messala, who, in [263 BC], was the first to exhibit a painting to the public; namely, a picture n one side of the Curia Hostilia that depicted the battle in which he had defeated the Carthaginians and Hiero in Sicily”, (‘Natural History’, 35: 7).

Cicero referred to it as tabula Valeria (Valerius’ picture), a landmark on the outside wall of the Curia, next to the tribune’s headquarters in the Forum on two occasions:

✴in 58 BC, in a letter to his daughter Tullia (‘Letters to Friends’ , 7 (14:2)), when expressing his regret that she had been summoned to appear before the tribunes; and

✴in 57 BC, in his cross-examination of the tribune P, Vatinius (‘in Vatunium’, 22) during the trial of P. Sestius (whom Cicero was defending).

Interestingly, the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus (as epitomised by Festus) recorded the commissioning of paintings by two other Roman commanders at about this time:

“The toga that is now called picta ... [is] depicted in the temples of Vertumnus and Consus, where [two commanders]:

✴M. Fulvius Flaccus in the former; and

✴[L.] Papirius Cursor in the latter;

are depicted in that way [i.e. wearing this type of toga] during their triumphs”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 228 Lindsay, translated by Eric Moormann, referenced below, at p. 20).

These frescoes are usually associated with two triumphs that are recorded in the fasti Triumphales:

✴the triumph of L. Papirius Crassus over the Tarentines in 272 BC; and

✴the triumph of M. Fulvius Flaccus over the Volsinians in 264 BC.

Aftermath of

According to Polybius, when the Carthaginians:

“... saw that Hiero had become their enemy, and that the Romans were becoming more deeply involved in the enterprise in Sicily, considered that they themselves required stronger forces in order to be able to confront their enemies and control Sicilian affairs. They therefore enlisted foreign mercenaries from the opposite coasts, many of them Ligurians, Celts and ... Iberians, and dispatched them all to Sicily. Perceiving that the city of Agrigentum had the greatest natural advantages for making their preparations, it being also the most important city in their province, they collected their troops and supplies there and decided to use it as a base in the war”, (‘Histories’, 1: 17: 3-4).

Varro, in Plin. NH 7.214, with praenomen M.; Cic. Fam. 14.2.2; Vat. 21, and Schol. Bob. ad loc.; Act. Tr.,

Plin. NH 35.22;

The fasti Triumphales recorded that C. Duilius , the consul of 260 BC, was awarded the first naval triumph in Roman history for his victory over the Sicilians and the Carthaginians. Christopher Dart and Frederik Vervaet (referenced below, at p. 270, citing Tanja Itgenshorst, referenced below, at note 2) noted that this was the first of eleven naval triumphs recorded in the extant fast1. As the able above records, no fewer than 17 triumphs were celebrated during the war, seven of which were naval triumphs. The distribution suggests that naval warfare was particularly important in 257-4 BC, and again in the final

The treaty that the Romans imposed on the Carthaginians was punitive: according to Polybius:

“At the close of the war, ... [the Romans and Carthaginians] made another treaty, the clauses of which [include the following]:

‘The Carthaginians are to:

✴evacuate the whole of Sicily and all the islands between Italy and Sicily ... ; and

✴pay 3,200 talents within 10 years, and a sum of 1,ooo talents at once ....’”, (‘Histories’, 3: 27: 1-6).

John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 19) estimated that these payments were equivalent to over 80 tonnes of silver.

Read more:

Hayes T. M., “The First Punic War: Deconstruction and Reinterpretation: a Hypothesis”, (2022) thesis of University College, London

Nantet E., “The Tonnage of the Syracusia: a Metrological Reconsideration”, (link opens a pdf) in:

“Under the Mediterranean: The Honor Frost Foundation Conference on Mediterranean Maritime Archaeology (20th – 23rd October 2017)”, (2022) online

Davies P., “Architecture Politics in Republican Rome”, (2017) Cambridge

Cornell T. C. (editor), “The Fragments of Roman History”, (2013) Oxford

Wilson R. J. A., “Hellenistic Sicily (ca. 270–100 BC)” in:

Prag (J. R. W., “The Hellenistic West: Rethinking the Ancient Mediterranean”, (2013) Cambridge, at pp. 79-119

Rosenstein N., “Rome and the Mediterranean 290 to 146 BC: The Imperial Republic”, (2012) Edinburgh

Dart C. J. and Vervaet F. J., ‘The Significance of the Naval Triumph in Roman History (260–29 BC)”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 176 (2011) 267–80

Moormann, E. M., “Divine Interiors: Mural Painting in Greek and Roman Sanctuaries”, (2011) Amsterdam

Zambon E., “Tradition and Innovation: Sicily between Hellenism and Rome” (2008) Stuttgart

tgenshorst, T., “Tota Illa Pompa: Der Triumph in der Römischen Republik”, (2005 ) Göttingen

Arnold-Biucchi C., Review of the book by Caccamo M. et al. (referenced below, 1997), Bryn Mawr Classical Review (2002)

Caccamo M. et al., “Siracusa Ellenistica: Le Monete ‘Regali’ di Ierone II, della sua Famiglia e dei Siracusani”, (1997) Messina

Forsythe G., “The Historian L. Calpurnius Piso Frugi and the Roman Annalistic Tradition”, (1994) Hoyos B. D., ‘The Rise of Hiero II: Chronology and Campaigns 275-264 BC’, Antichthon, 19 (1985) 32-56

Lazenby J. F., “Hannibal's War: A Military History of the Second Punic War”, (1978) Warminster

Walbank F. W., “A Historical Commentary on Polybius: Vol. I, Commentary on Books I–VI”, ( 1957) Oxford