Rome’s Existing Treaty with the Samnites (354 BC)

As described in my page on the Renewed Latin Peace to Start of 1st Samnite War (358 - 343 BC), Livy recorded that a number of Roman successes in 354 BC had:

-

“... induced the Samnites to ask for amicitia (formal relations of friendship). Their envoys received a favourable reply from the Senate, and were accepted as foedere in societatem (allies with a treaty)”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 19: 3-4).

Rafael Scopacasa (referenced below, 2015, at p. 129) observed that:

-

“It is clearly being suggested here that the Samnites became aware of Rome’s military supremacy and decided to secure a good relationship with this rising power. [However], if we move away from Livy’s Rome-centred viewpoint, we may infer that a very similar set of anxieties probably motivated Rome to agree a treaty with the Samnites.”

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 197) noted that the amicitia requested by the Samnites at this point implied:

-

“... an undertaking not to engage in aggression in the sphere of interest of a friendly state and not to help her enemies. Strictly speaking, it was to be distinguished from societas [the status that the Romans gave the Samnites in the treaty ... [but] the two terms were often interchangeable. It is hard to see any distinction between them in [the passage above].”

He observed (at p. 198) that:

-

“It is almost invariably held that this treaty established the river Liris (modern Garigliano) as the line demarcating Roman and Samnite spheres of influence. This is entirely plausible, but rests only on [the] indirect testimony [of later events].”

In other words, later events suggest that the Samnites recognised Rome’s actual or prospective hegemony north and west of the Liris and that, in return, Rome recognised that the territory to the east and south of the river (including Campania) lay within the Samnites’ sphere of influence.

Events of 343 BC

Consular Elections

According to Livy, at the end of the consular year of 344 BC:

-

“The state, for no recorded reason, reverted to an interregnum, which was followed (perhaps as had been intended) by the election to the consulships of two patricians: M. Valerius Corvus, for the third time; and Aulus Cornelius Cossus”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 28: 10).

In the preface to his account of the First Samnite War, Livy characterised their consular year (343 BC) as the year in which:

-

“... the [Roman] sword was [first] drawn against the Samnites, a people powerful in arms and in resources ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 29: 1-2).

It is certainly possible that, as Livy suspected, the use of an interrex to preside over the consular elections had in some way facilitated the election of two patricians, in contravention of the Lex Licinia Sextia of 367 BC. It is also possible, as Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at p. 271) suggested, this law was disregarded (on this and other occasions)”

-

“... in large measure [because of] a desire to have proven commanders in charge of Rome’s armies at times of expected crisis.”

Causes of the War

It seems odd to find the Romans and Samnites at war only eleven years after the agreement of the treaty of friendship between them. However, according to Livy, the war:

-

“... was of external origin rather than of [the Romans’] own making. The Samnites had unjustly attacked the Sidicini, ... [who had turned for help] to the Campani. ... The Samnites, disregarding the Sidicini and attacking the Campani, ... seized and ... occupied [the Monti Tifatini], a range of hills looking down on Capua, before descending in battle-order into the plain that lies between. A second battle was fought there, in which the Campani, being worsted, had been shut up within their walls ... [and] driven to seek assistance of the Romans”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 29: 3-7).

The Campanian request for help was delicate, given the Romans’ recently-agreed treaty with the Samnites, and (at least according to Livy), the Romans initially refused it. However, the Campani then made them an offer that was too good to refuse:

-

“Since you decline to ... [protect] what belongs to us, you will at least defend your own [possessions]; therefore, we surrender [to Rome] ... populum Campanum urbemque Capuam (the people of Campania and the city of Capua), together with our lands, the shrines of our gods and everything else [that we possess]; whatever we endure henceforth, we shall endure as your surrendered subjects”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 31: 3-4).

In other words, Livy contrived to show that external circumstances had forced the Romans into a position in which war with their erstwhile Samnite friends became inevitable.

Rafael Scopacasa (referenced below, 2015, at p. 131)argued that:

-

“If we look beyond Livy’s suspiciously neat chain of events [that led to war], it seems likely that hostilities may have been sparked by competition between a number of entities, [not least among whom were the Romans and the Samnites], all of which had vested interests in Campania and its rich natural resources.”

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at pp. 15-6) argued that the Roman advance into the territory of the Aurunci in 345 BC (described in my page on the Renewed Latin Peace to Start of 1st Samnite War (358 - 343 BC)) had paved the way for a subsequent advance into the fertile territory of Capua, and it is possible that the Samnite advance into the territory of the Sidicini was their response. In other words, it is possible that this war began as a contest to decide whether Capua should fall to the Romans or the Samnites. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 284) pointed out that:

-

“... Capua was still a large and perhaps even great city, but her military forces were not sufficient to withstand aggression from either Rome or the Samnites, [and was therefore] a tempting prize for [either of them].”

In other words, whether or not Livy’s reconstruction of events is entirely accurate, there is no doubt that Capua was forced to choose between Rome and Samnium in 343 BC, and that she chose Rome.

Capua and the Campani

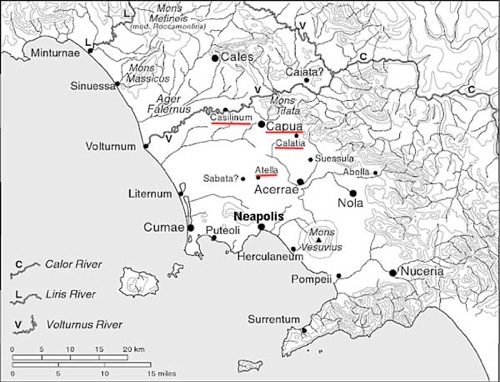

Adapted from Michael Fronda (referenced below, at p. xxi: Map 8: Campania)

Underlined in red: Capua and its satellites: Atella; Casilinum; and Calatia

Roman historians believed (probably correctly) that Capua had been an Etruscan city until 423 BC, when it had been taken by ‘the Samnites’. However, as Rafael Scopacasa (referenced below, 2015, at p. 128) pointed out:

-

“... the Samnites who, according to Livy, descended towards Campania in the late 5th century BC were probably not the same Samnites who are [said to have agreed] a treaty with Rome in 354 BC.”

He acknowledged (at p. 127) that, by the time of the First Samnite War:

-

“... the use of the Oscan language [at Capua and the surrounding territory] ... affords palpable evidence of Campania’s connection with Samnium.”

Nevertheless:

-

“... the archeological record at Capua shows no sign of abrupt or violent change after the alleged Samnite takeover[in 423 BC]. Quite to the contrary, excavations and surveys have revealed substantial continuity with the preceding Etruscan phase ..., especially as regards the organisation of the city’s territory, with the main urban centre surrounded by a number of outlying villages. ... Rather than the outcome of a ‘Samnite’ conquest or migration, [the spread of Oscan to Capua] can be seen as a key stage in the long-term process of interregional interaction.”

In other words:

-

✴the Samnites and the people of Capua both used the Oscan language by this time; but

-

✴while the Samnites of the Apennines eschewed urbanisation, Capua still retained the ‘city-state’ culture of its Etruscan and Greek colonial past.

We ought to stop for a moment and look at Livy’s use of the expressions ‘Campani’ and ‘people of Campania’: in the records reproduced above:

-

✴the ‘Campani’ sought the protection of Rome in 343 BC; but

-

✴the ‘people of Campania and the city of Capua’ surrendered to Rome in order secure it.

According to Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 289):

-

“The Campani were the inhabitants of Capua ....”

However, it is possible that ‘the people of Campania’ indicated a larger group of people. For example, in 342 BC (see below), the new consul, C. Marcius Rutulus was:

-

“... assigned Campania for his province ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 38: 8); and

the army that he took over had been:

-

“...had been distributed among the cities of Campania ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 38: 10).

As Michael Fronda (referenced below, at p. 128) pointed out, this implied:

-

“... that more cities than just Capua had been placed under Roman protection [at this point].”

-

✴Fronda (as above) also noted that:

-

“Most scholars agree that Capua was the hegemonic power in Campania, dominating a cluster of subordinate or satellite cities including Atella, Calatia, [the now-unknown] Sabata and Casilinum.”

-

✴Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 290) also identified Capua in the first half of the 4th century BC as the:

-

“... mistress of smaller neighbouring communities like Atella, Casilinum and Calatia”

-

Thus, although it is impossible to be certain, it seems likely that Capua included Atella, Casilinum and Calatia in its surrender [to Rome], and it is possible that Cumae also surrendered to Rome at this point.

In short, it is possible that, as well as Capua, Atella, Casilinum and Calatia all surrendered to Rome in 343 BC. As Dexter Hoyos (in Yardley and Hoyos, referenced below, at p. 318) argued (reasonably, in my view):

-

“The [designations Campani or Campanians] apply in Livy, not to all Campania’s communities, but to [the people of] ... Capua and its subordinate cities, like Atella and Casilinum.”

In what follows, I therefore assume that Livy’s Campani / Campanians were the people of Capua, Atella, Casilinum and Calatia.

Some scholars doubt that Capua and the other Campani would have voluntarily surrendered to Rome in order to escape the greater misfortune of Samnite hegemony. However, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at pp. 287-8) observed that:

-

“[Although] the Romans often referred to states seeking their protection as coming into their fides, ... they also used the term ‘deditio (in fidem)’ for many of these appeals, and regarded the juridicial status [of such states] as technically the same as that of an enemy that had been defeated in war and then surrendered. [However], in reality, ... [cities] that had appealed [to Rome for protection as the Campani had done were] almost invariably treated differently from a defeated opponent.”

In other words, Livy might well have over-stated the reluctance with which the Romans broke the putative terms of their treat with the Samnites, but this does not necessarily mean that he or his sources had been driven to invent the deditio (‘surrender’) of Capua and the Campani.

War with Samnium (343-1 BC)

Declaration of War

Having accepted hegemony over Capua and the Campani, the Romans sent envoys to the Samnites:

-

“... to request that, out of regard for the friendship and alliance of the Romans, [they] would ... make no hostile incursion into a territory that now belonged to Rome. If soft words proved ineffectual, they were to warn the Samnites, ... not to meddle with the city of Capua or the Campanian domain”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 31: 9-10).

However, these overtures were rebuffed, and:

-

“When the news of [this] reached Rome, the Senate ... sent fetials to demand redress: when they failed to obtain it, they declared war [on the Samnites] in the customary fashion. ... both consuls took the field, Valerius marching into Campania and Cornelius into Samnium”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 32: 1-2).

Campaign of 343 BC

Valerius’ Victory at Mount Gaurus

Valerius marched to the relief of the Campani, where the Samnites were expecting him, and camped at the foot of the mons Gaurus, east of Cumae (‘History of Rome’, 7: 32: 2). Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 310) defended Livy’s location of this battle near Cumae and the one that followed it (see below) at Suessula , suggesting that the Samnites had probably effected a two-pronged attack on Cumae and Capua. The great part of Livy’s account of this first engagement is taken up with:

-

✴an account of Valerius’ speech to his men as they prepared for the battle (‘History of Rome’, 7: 32: 5-17); and

-

✴Livy’s own assessment of Valerius’ character and his skill as a military commander(‘History of Rome’, 7: 33: 1-5)

I discuss the content of these passages below. Livy then gave a long account of the battle, which actually tells us little more than that it was hard-fought and, for most of the day, evenly-balanced (‘History of Rome’, 7: 33: 5-14): as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 310) observed, battle scenes in the early books of Livy are generally invented or heavily elaborated:

-

“ ... and the historic first [Roman] engagement with the Samnites at the mons Gaurus is particularly likely to have been worked up by both earlier annalists and Livy himself.”

Eventually:

-

“... there were signs of [the Samnites] giving way and the beginning of a rout; then, many Samnites were captured or killed, and many more would have succumbed if night had not ended what was now a victory rather than a battle. The Romans admitted that they had never fought with a more stubborn adversary; and the Samnites, on being asked what it was that had [caused them to panic], ... replied that it was the Romans’ eyes, which had seemed to blaze, and their frenzied expressions ... This panic was manifest, not only in the outcome of the battle, but also in the Samnites’ subsequent retreat under cover of night. In the morning, the Romans took possession of the deserted camp, and the whole population of Capua streamed out to congratulate [Valerius and his men, presumably as they returned to the city]”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 33: 15-18).

Cornelius’ Victory near Saticula

At about the time that Valerius established his camp near the mons Gaurus, Cornelius established his near Saticula. According to Livy, as the people of Capua assembled to celebrate Valerius’ victory;

-

“... this rejoicing came near to being marred by a great reverse in Samnium: for the consul Cornelius, marching from Saticula, had unwarily led his army into a forest which was penetrated by a deep defile, and was there beset on either hand by the enemy; nor, until it was too late to withdraw with safety, did he perceive that they were posted on the heights above him”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 34: 1-2).

Publius Decimus Mus to the Rescue

Livy described at great length how military tribune, P. Decius Mus, saved the situation. Much of his account is in the form of Decius’ speeches to his men and his conversations with Cornelius, the content of which I discuss below.

This famous rescue began when Decius realised that, if he could reach the top of a nearby hill, he could distract the Samnites and provide cover, allowing the main body of the army to escape. Cornelius agreed to the plan and Decius duly advanced with a small detachment:

-

“... under cover through the wood, so that the enemy did not notice him till he had nearly reached the [top]. The Samnites ... were overcome with astonishment and dread: they all turned and gazed at him [as he completed the ascent], giving Cornelius time to lead his army to more favourable ground ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 34: 7-8).

Then, very early on the following morning, Decius surprised the Samnites who were surrounding the hill by leading his men in their direction:

-

“A [Samnite] sentry was awakened ... [at which point], Decius, seeing that they were discovered, gave the order to his men, and they set up such a shout that the Samnites, who had been stupefied with sleep were now also breathless with terror and incapable of arming themselves and making a stand ... During the Samnites’ fright and confusion, [Decius’ men] cut down such [Samnite] guards as they came across and proceeded towards Cornelius’ camp”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 36: 1-5).

Decius’ arrival unsurprisingly prompted great rejoicing in the Roman camp:

-

“When word was sent round that those who had exposed themselves to great danger for the safety of the others were themselves returning safe and sound, [all the men in the camp] poured out to welcome, praise and congratulate them. They called [the returning men] their saviours, offered praise and thanks to the gods, and extolled Decius to the skies. This was a castrensis triumphus [see below] for Decius: he marched through the centre [of the camp ?] with his detachment still under arms, and all eyes were on him him, and the men put him on a level with Cornelius, according him every honour. When they reached headquarters, Cornelius bade the trumpet sound an assembly and fell to lauding Decius, as he deserved”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 36: 7-9).

However, ever the military man, Decius had more important matters in mind: according to Livy, he interrupted Cornelius while he was in full flow, suggesting that:

-

“... he defer his speech, and that all other considerations should also be postponed: instead, he persuaded Cornelius to attack the enemy while they ... [were still] bewildered by the alarm of the night and dispersed in separate detachments about the hill [from which Decius had descended]”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 36: 9).

Cornelius’ Victory

Thus, at Decius’ suggestion, Cornelius led his army out of their camp:

-

“... in the direction of the enemy, who were caught quite off their guard by this surprise attack: ... the Samnite soldiers were widely scattered and most of them were unarmed ... they were first driven headlong into their camp, but the sentries were routed and the camp itself was taken. The [noise of battle] was heard all round the hill and sent the [Samnite] detachments flying from their various stations. Thus, a great part of the Samnites fled without coming into contact with the enemy. ... some 30,000, were caught in the camp and put to the sword ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 36: 11-13).

Honours Awarded to Decius

As noted above, Livy described Decius’ return to the Roman camp after he had rescued the army from the Samnite ambush as:

-

“... a castrensis triumphus [triumph in the camp] for Decius: he marched through the centre [of the camp ?] with his detachment still under arms, and all eyes were on him him. The men put him on a level with Cornelius in according him every honour”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 36: 8).

Henk Versnel (referenced below, at pp. 377-8) pointed out that a military tribune such as Decius, who lacked imperium, was not allowed to triumph, and that, in the phrase ‘castrensis triumphus’:

-

“... Livy uses metaphorical language here, but the terminology remains remarkable all the same.”

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 349 observed that the phrase indicates:

-

“... an easily understood concept, but one which I have been unable to parallel elsewhere.”

Mary Beard (referenced below, at p. 266) characterised Livy’ expression as a:

-

“... striking phrase, which is most likely a clever coinage by Livy but, just conceivably, an otherwise unattested piece of technical triumphal vocabulary ...”

It is significant that it was the soldiers that awarded this ‘triumph in camp’ to Decius, whom (according to Livy) they explicitly recognised as as on a level with the consul Cornelius: they presumably fely that he had earned imperium by his actions.

When the Romans returned to their camp after Cornelius’ subsequent victory over the Samnites:

-

“Cornelius called an assembly and pronounced a panegyric upon Decius, in which he rehearsed his former services [to Rome] and the fresh glories that his bravery had achieved. Besides other military gifts, he bestowed on him a golden crown and 100 oxen, one of which was a choice white one, fat and with gilded horns. ... Following Cornelius’ award, the legions ... placed the corona graminea [a ceremonial wreath of grass often referred to as a grass crown] on Decius's head to signify that he had rescuing them from a siege; and his own detachment crowned him with a second wreath, indicative of the same honour. Adorned with these insignia, Decius sacrificed the choice [white] ox to Mars ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 37: 1-3).

Pliny the Elder gave a clear description of the corona graminea:

-

“Of all the crowns with which, in the days of its majesty, [Rome] ...rewarded the valour of its citizens, there was none attended by higher glory than the corona graminea. ... it was only ever:

-

✴conferred in a crisis of extreme desperation;

-

✴voted by the acclamation of the whole army; and

-

✴only to a man who had been [that army’s] preserver.

-

While other crowns were awarded by the imperatores (commanders) to the soldiers, the corona graminea [was awarded] by the soldiers to the imperator ... [when] a whole army had been saved and was indebted for its preservation to the valour of a single individual. This crown ... was made from grass gathered on the spot where the troops so rescued had been beleaguered”, (‘Natural History’, 22: 4).

Pliny noted that, although such awards were very rare:

-

“Some commanders ... have been presented with more than one of these crowns: for example, the military tribune P. Decius Mus ... received one from his own army and another from the men whom he had rescued when surrounded”, (‘Natural History’, 22: 5).

He also noted that:

-

“In addition to the persons already mentioned, the honour of this crown has been awarded to M. Calpurnius Flamma, then a military tribune in Sicily; but up to the present time, it has been given to only a single centurion, Cnaeus Petreius Atinas, during the war with the Cimbri. This soldier, while acting as primipilus under Catulus, on finding all retreat for his legion cut off by the enemy, harangued the troops and, after slaying his tribune, who hesitated to cut a way through the encampment of the enemy, led the legion in safety. I find it stated by some authors that, in addition to this honour, this same Petreius, clad in the prætexta, offered sacrifice at the altar, to the sound of the pipe, in presence of the then consuls, Marius and Catulus”, (‘Natural History’, 22: 6).

Valerius’ Victory at Suessula

According to Livy:

-

“A third engagement was fought at Suessula, since, after the rout inflicted on them [near the mons Gaurus], the Samnites had mustered all the men they [still] had of military age, determined to try their fortune in a final encounter. The alarming news was carried from Suessula to Capua, with messages imploring assistance. The soldiers were immediately mobilised and, and leaving behind their baggage and a strong garrison for the camp, made a rapid march and camped within a short distance of the enemy ... The Samnites, assuming that the battle would not be delayed, formed up in line; then, since the Romans did not come out to meet them, they advanced against the Roman camp. When they [realised the small size of the Roman camp], , the whole army began to murmur that they ought to ... [take it by storm] and their rashness would have brought the war to a conclusion, had not the [Samnite] commanders restrained the ardour of their men”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 37: 1-3).

Instead, the Samnites dispersed in order to find provisions for their huge army:

-

“Seeing the Samnites dispersed about the fields and their stations thinly manned, Valerius ... led [his men] to the assault of the Samnite camp. Having taken it at the first attempt, ... , he marched out in serried column and, sending the cavalry ahead to surround the scattered Samnites ... he made a prodigious slaughter of them. ... so great was their discomfiture and panic that the Romans brought in to Valerius some 40,000 forty [captured] shields (although far fewer) had been killed) ... The victorious army then returned to the Samnite camp and the plunder there was all given to the soldiers (‘History of Rome’, 7: 37: 12-17).

Triumphs of 343 BC

After these battles:

-

“Both the consuls celebrated a triumph over the Samnites (‘History of Rome’, 7: 38: 3).

The fasti Triumphales also record that:

-

✴[M. Vale]rius Corvus, as consul for the third time, was awarded his second triumph, this one over the Samnites on [the 21st September]; and

-

✴his colleague, [Aulus Cor]nelius Cossus Arvina was awarded a triumph over the Samnites [on the following day].

Livy noted that:

-

“A striking figure in the [consuls’ triumphal] procession was Decius, wearing his decorations: in their crude jokes, the soldiers repeated his name as often as those of the consuls” (‘History of Rome’, 7: 38: 3).

These jokes were a usual feature of such processions and, in this case, would have included references to the names Corvus (crow), Cossus (woodworm) and Mus (mouse). Decius’ decorations would have been those that he had received in the camp at Saticula

Livy recorded that, following:

-

“... the success that attended the campaign of 343 BC:

-

✴... the people of Falerii became anxious to convert their 40 years' truce into a permanent treaty of peace with Rome; [and]

-

✴... the Latins abandoned their designs against Rome, and instead employed the force they had assembled against the Paelignians.

-

[Furthermore], the fame of these victories was not confined to Italy; even the Carthaginians sent a deputation to congratulate the Senate, and to present a golden crown that weighed 25 pounds was to be placed in the chapel of Jupiter on the Capitol”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 38: 1).

Samnite Surrender (341 BC)

Rome was beset by internal problems throughout 342 BC (see below). Livy thus recorded no further action against the shattered Samnites until 341 BC, when:

-

“The consul Lucius Aemilius Mamercus, having entered Samnite territory, nowhere encountered a Samnite camp or levies. As he was ravaging their fields... , he was approached by Samnite envoys, who begged for peace. Aemilius referred the envoys to the Senate, ... where they pleaded with Romans to grant them peace and the right to war against the Sidicini ... , a people who had always been [hostile to Samnium] and who had never been friendly to Rome; neither were they under the protection of the Roman people, nor yet their subject. Titus Aemilius, the praetor, laid the Samnites’ petition before the Senate, which voted to renew the treaty with them”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 1: 7-10).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at pp. 308-9) observed that

-

“... if one accepts that Rome won some kind if victory in the period 343-1 BC, then much else follows:

-

✴the Samnites were forced to ... acquiesce in Roman control of Campania; although

-

✴... they remained strong enough to ensure that [their treaty with Rome] of 354 BC was restored, ,,,[allowing them a free hand to] attack the Sidicini ...

-

However, the renewed allowance alarmed the towns and tribes lying between their territories ... : hence the alliance of Latins, Campanians, Volsci, Sidicni and Aurinci ... fought against the Romans and Samnites in the Latin War of 340 BC.”

Sedition of 342 BC

Livy recorded that the consuls of 342 BC were:

-

“... C. Marcius Rutilus, to whom Campania had been allotted as his province ... [and] Q. Servilius, [who remained] in the City ... [Marcius was particularly well-experienced, having] been consul four times, as well as dictator and censor ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 38: 8-9).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p, 361) pointed out, the sources available to Livy clearly fell into two groups, each of which followed a particular historical tradition that was incompatible with the other. Livy set out his preferred tradition in detail, and then quickly described the tradition recorded by ‘other annalists’ in terms of the differences between the two. He concluded that:

-

“... the ancient authorities [for these two traditions] agree on nothing but the simple fact that there was a mutiny [in 342 BC], and that it was suppressed”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 42: 7).

Read more:

R. Scopacasa , “Ancient Samnium: Settlement, Culture, and Identity between History and Archaeology”, (2015) Oxford

J. C. Yardley (translation) and D. Hoyos (introduction and notes), “Livy: Rome's Italian Wars: Books 6-10”, (2013), Oxford World's Classics

M. Fronda, “Between Rome and Carthage: Southern Italy during the Second Punic War”, (2010) Cambridge

M. Beard, “The Roman Triumph”, (2007) Cambridge (Ma.) and London

G. Forsythe, “A Critical History of Early Rome: From Prehistory to the First Punic War”, (2005) Berkeley Ca.

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume II: Books VII and VIII”, (1998) Oxford

T. Cornell, “The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (ca. 1000-264 BC)”, (1995) London and New York

H. S. Versnel , “Triumphus: An Inquiry Into the Origin, Development and Meaning of the Roman Triumph”, (1970) Leiden

Return to Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)