Roman Italy (1st century BC)

First Triumvirate (43 - 38 BC)

Roman Italy (1st century BC)

First Triumvirate (43 - 38 BC)

Formation of the Triumvirate (late 43 BC)

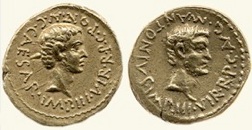

Aureus struck by Octavian in Cisalpine Gaul (RRC 493/1, late 43 BC)

Obverse: C·CAESAR·IMP·III·VIR·R·P·C·PONT·A͡VG: Head of Octavian (bearded)

Reverse M·ANTONIVS·IMP·III·VIR·R·P·C·A͡VG: Head of Mark Antony (bearded)

III·VIR·R·P·C = triumvir rei publicae constituendae, an unprecedented formal title

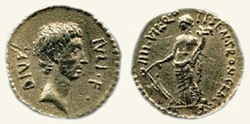

Aurei struck by Mark Antony in Cisalpine Gaul (late 43 BC)

Obverse: M·ANTONIVS·III·VIR·R·P·C: Obverse: M·ANTONIVS·III·VIR·R·P·C:

Head of Mark Antony, with lituus Head of Mark Antony, with lituus

Reverse: C·CAESAR·III·VIR·R·P·C: Reverse: M·LEPIDVS·III·VIR·R·P·C:

Head of Octavian (bearded) Head of Lepidus, with aspergillum and simpulum

According to Appian, in late 43 BC:

“Octavian and [Mark] Antony composed their differences on a small, depressed islet in the river Lavinius, near the city of Mutina. [Cassius Dio, at ‘Roman History’, 46: 54: 3, placed this meeting at nearby Bononia.] Each had five legions of soldiers whom they stationed opposite each other, after which each proceeded with 300 men to the bridges over the river. Lepidus, who had gone before them, searched the island and waved his military cloak as a signal to them to come. Then, [Octavian and Mark Antony each left their men on the bridges and advanced to the middle of the island, ... [where] the three sat together in council, Octavian in the centre because he was consul. They were in conference from morning till night for two days, and came to these decisions:

✴that Octavian should resign the consulship and that -the praetor, P.] Ventidius should take it for the remainder of the year;

✴that a new magistracy for suppressing civil dissensions should be created by law, which Lepidus, Antony, and Octavian should hold for five years with consular power (for this name seemed preferable to that of dictator, perhaps because of Antony's decree abolishing the dictatorship);

✴that these three should at once designate the yearly magistrates of the city for the five years;

✴that a distribution of the provinces should be made:

•[Mark] Antony would receive the whole of Gaul except the part bordering the Pyrenees Mountains, which was called Old Gaul;

•Lepidus would receive Old Gaul and Spain; and

•Octavian would receive Africa, Sardinia, Sicily and the other nearby islands.

Thus was the dominion of the Romans divided by the triumvirate among themselves”, (‘Civil Wars’, 4: 2:1 - 3:1).

Cassius Dio recorded that:

“It was further agreed that, [as triumvirs]:

✴they would [collectively] bring about the murder of their personal enemies;

✴Lepidus, after being appointed consul [for 42 BC] in place of Decimus, would keep guard over Rome and the remainder of Italy; while

✴[Mark Antony and Octavian] would make an expedition against Brutus and Cassius.

They confirmed these arrangements by oath”, (‘Roman History’, 46: 53: 6).

Cassius Dio then recorded that:

“... in order that the soldiers might ostensibly ... witness [this secret agreement, Mark Antony, Lepidus and Octavian] called them together .. [and told them] all that it was proper and safe to tell them. Meanwhile, [Mark] Antony’s soldiers (obviously having received prior orders) recommended to [Octavian that he should marry] the daughter of Fulvia, [Mark] Antony's wife], whom she had by Clodius. [The young lady in question was Clodia Pulchra, Fulvia’s daughter by her first husband, P. Clodius Pulcher, who had been murdered in 52 BC]. Despite the fact that Octavian was already betrothed to another, he did not refuse [the hand of] Clodia ... ”, (‘Roman History’, 46: 53: 6).

Cassius Dio had earlier recorded that, shortly after Caesar’s murder in 44 BC, Mark Antony (then consul) had given:

“... his daughter, [Antonia, from his second marriage, to his cousin, Antonia Hybrida] in marriage to Lepidus’ son and made arrangements to have Lepidus himself appointed as pontifex maximus, so as to prevent his meddling with what he himself was doing”, (‘Roman History’, 44: 53: 6).

Lex Titia (27th November 43 BC)

According the Appian:

“Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus entered the City separately on three successive days, each with his praetorian cohort and one legion. As they arrived, the City was speedily filled with arms and military standards, disposed in the most advantageous places. A public assembly was forthwith convened in the midst of these armed men, and a tribune, P.Titius, proposed a law providing for a new magistracy for settling the present disorders, to consist of three men, namely, Lepidus, Antony, and Octavian, to hold office for five years with the same power as consuls. ... No time was given for scrutiny of this measure, nor was a fixed day appointed for voting on it, but it was passed forthwith”, (‘Civil Wars’, 4: 7).

The Augustan fasti Colotiani recorded that:

“[M.] Aemilius, [[M. Antonius,]] Imperator Caesar: IIIviri rei publicae constituendae (triumvirs for the restoration of the state), from the 27th November 43 BC, [presumably the date of the lex Titia] to the 6th December 38 BC”

As Michael Crawford (referenced below, at p. 740) observed:

“... both [Mark Antony] and Octavian celebrated the event with issues of portrait gold [illustrated above] ...”

Augustus (as Octavian became in 27 BC) made two references to his appointment as triumvir in 43 BC in his ‘Res Gestae’:

✴“In [43 BC], the people appointed me:

•as consul after both consuls had fallen in war, and [then]

•[as] IIIvir rei publicae constituendae”, (‘Res Gestae’, 1: 4, translated by Alison Cooley, referenced below, at p. 59); and

✴“I was one of the IIIviri rei publicae constituendae for ten consecutive years, (‘Res Gestae’, 7: 1, translated by Alison Cooley, referenced below, at p. 65).

This was extremely economical with the truth: as Alison Cooley (referenced below, at p. 114) pointed out:

“After having extorted the consulship by threats of violence [in 43 BC], Octavian promptly resigned from the post in order to join ranks with [Mark] Antony and Lepidus as triumvir”

She also noted (at 133) that the triumvirate had been negotiated between the parties in secret and the lex Titia, which conferred the appearance of legitimacy on these proceedings:

“... was voted into effect immediately, without the statutory wait for three days between prposal and vote, to allow for scrutiny of the measure. In theory, the triumvirs received consular powers, but they took upon themselves the tasks of [immediately] appointing ... magistrates for each of their five years in office and of sharing out the provinces between themselves.”

Proscriptions

According to Appian, having made their agreement at Bononia, and while they were still together on the island in the river there, Octavian, Mark Antony and Lepidus:

“... joined in making a list of those who were to be put to death. They put on the list:

✴those whom they suspected because of their power;

✴ heir personal enemies ... ; and

✴[a number of wealthy individuals], because they needed a great deal of money to carry on the war (since the revenue from Asia had been diverted to Brutus and Cassius ... and Europe and especially Italy were exhausted by wars and exactions).

They also levied very heavy contributions from the plebeians and even from women, and contemplated taxes on sales and rents. ... The number of senators who were sentenced to death and confiscation was about 300, and of the knights about 2,000. The list of the proscribed included brothers and uncles of the triumvirs and also some of the officers serving under them... . As they left the conference to proceed to Rome, they postponed the proscription of the greater number of victims, but they decided to send executioners in advance and without warning to kill [a few of] the most important ones, among whom was Cicero. Four of these were slain immediately, [which caused the sort of panic that would be expected] in a captured city: when it became known that men were being seized and massacred, although there was no list of those who had been previously sentenced, every man thought that he was [about to be next. In an attempt to end the panic], the consul Pedius hurried around with heralds, urging everyone to wait till daylight and get more accurate information. When morning came, Pedius, contrary to the intention of the triumvirs, published a list of 17 men who were considered to be the sole authors of the civil strife and the only ones condemned. To the rest he pledged the public faith, being ignorant of the determinations of the triumvirs. Pedius died in consequence of fatigue the following night”, (‘Civil Wars’, 4: 5-6).

An eye-witness account of the vagaries of the proscriptions survives in Cornelius Nepos’ biography of T. Pomponius Atticus:

“When [Mark Antony] returned into Italy [in late 43 BC], everyone thought that Atticus would be in great peril, on account of his closeness to both Cicero and Brutus. He accordingly withdrew from the forum ... and lived in retirement at the house of P. Volumnius, to whom... he hadrecently given assistance; (such were the vicissitudes of fortune in those days ... ) ... However, [Mark Antony], although he was moved with such hatred towards Cicero that he [also proscribed] all his friends, ... [was nevertheless] mindful of the obliging conduct of Atticus; and, after ascertaining where he was, wrote to him with his own hand, assuring him that he need be under no apprehension, but might come to him immediately ... When [Atticus] had delivered himself from these troubles, his only concern was to assist as many people as possible, by whatever means he could. Thus, while the common people, in consequence of the rewards offered by the triumvirs, were searching for the proscribed, no one went into Epirus, [where Atticus had a large estate], without finding a supply of everything and full permission to stay there permanently”, (‘Life of Atticus’, 10:1 - 11:1).

As I discussed on my page Octavian 44 -43 BC, Octavian and Q. Pedius, as consuls in 43 BC, had already instituted legal proceedings against those who had actually or allegedly conspired to murder or had actually murdered Caesar. However, as Kathryn Welch (referenced below, 2014, at p. 145) observed:

“The sources are in agreement ... on the matter of punishment: [at this point, it involved] interdiction rather than summary execution.”

Augustus referred to these earlier proceedings in his ‘Res Gestae’:

“Those who killed my father [i.e., Caesar], I banished through legitimate trials, exacting vengeance for their sacrilege ... , (‘Res Gestae’, 2, translated by Alison Cooley, referenced below, at p. 60).

However, the ‘Res Gestae’ contains no reference to the subsequent triumviral proscriptions. As Kathryn Welch (referenced below, 2014, at p. 138) observed

“It is true, as commentators have suggested, that [Augustus’] referring only to the court process must have been an important strategy for avoiding any mention of [these infamous] proscriptions.”

However, she argued (at p. 161) that Augustus. motives went beyond this:

“The Pedian court and the [triumviral] proscriptions were separate responses to the punishment of Caesar’s murderers. The trials [under the lex Pedia] should not be seen as a prelude to the proscriptions and the proscriptions should not be regarded as an inevitable extension of the [‘Pedian’ process. In fact, the two programs arose from the intense competition between [Octavian and Mark Antony] for the title of ultor Caesaris, [(avenger of Caesar)].

✴In August 43 BCE, [Octavian] took advantage of his position as consul to bring the assassins to trial and convict them quickly, even before he restored full citizen status to Antonius and Lepidus.

✴Later, he had no reason to mention proscription in the ‘Res Gestae’ and every reason to remain silent about it, not merely because it became the most hated episode of the era but because it [would have] enabled [Mark Antony and Lepidus] to claim partial credit in a cause he had always wanted and needed to make entirely his own.

Triumphs of Plancus and Lepidus (late December)

The Augustan fasti Triumphales record two triumphs in 43 BC:

✴L. Munatius, proconsul, from Gaul (29th December)

✴M. Aemilius Lepidus (II), triumvir r.p.c., proconsul, from Spain (31st December)

Plancus’ epitaph (CIL X 6087, ca. 15 BC) at Gaieta (on the coast to the north of modern Naples) recorded that:

“... triump ex Raitis; aedem Saturni fecit de manibis ...” (he ... triumphed over the [Gallic tribe of the] Raetians; founded the Temple to Saturn with the spoils of war; ...)

Velleius Paterculus recorded that:

“... [Mark] Antony had L. Caesar, his uncle, placed upon the list, and Lepidus his own brother Paullus. Plancus also had sufficient influence to arrange for his brother Plancus Plotius to be enrolled among the proscribed. Thus, the troops who followed the triumphal car of Lepidus and Plancus kept repeating (among the traditional soldiers' jests but amid the execrations of the citizen) that:

'De germanis non de Gallis duo triumphant consule’ (our two consuls triumph over [their brothers], rather than over the Gauls)”, (‘Roman History’, 2: 67: 4).

The brothers in question were (allegedly): L. Aemilius (Lepidus)? Paullus; and L. Plautius Plancus (who was originally named C. Munatius Plancus before his adoption by a L. Plautius). However, as Hannah Mitchell (referenced below, at p. 14) pointed out:

✴there are factual problems with his passage:

•neither Plancus nor Lepidus was consul in 43 BC;

•they triumphed separately (on 29 and 31 December 43); and

•Lepidus triumphed ex Hispania; and

✴it might well have been distorted to conform with Velleius’ consistent bias in favour of Octavian (at the expense of Mark Antony, Lepidus and Plancus).

Events of 42 BC

Cassius Dio recorded that:

“It was further agreed that, [as triumvirs]:

they would [collectively] bring about the murder of their personal enemies;

Lepidus, after being appointed consul [for 42 BC] in place of Decimus, would keep guard over Rome and the remainder of Italy; while

[Mark Antony and Octavian] would make an expedition against Brutus and Cassius.

They confirmed these arrangements by oath”, (‘Roman History’, 46: 53: 6).

Lepidus and Plancus served as consuls in this year, which meant that Lepidus could remain in Rome while Mark Antony and Octavian dealt with Cassius and Brutus (now the most prominent of Caesars’ assassins).

Cult of Divus Julius

According to Cassius Dio, on the first day of 42 BC, the triumvirs:

“... took an oath and made all the rest swear that they would consider all [of Caesar’s] acts binding ... They also:

✴laid the foundations of [the Temple of Divus Julius] in the Forum, on the spot where his body had been burned;

✴caused an image of him, together with an image of Venus, to be carried in the procession at the Circensian games;

✴decreed that, whenever news came of a [Roman] victory anywhere, a thanksgiving should be made to the victor by himself and also to Caesar (though dead) ... ;

✴compelled everybody to celebrate [Caesar’s] birthday ... [albeit that, since the actual day fell during] the ludi Apollinares, they decreed that his ‘official’ birthday] should be celebrated on the previous day ... ;

✴made the day on which Caesar had been murdered ]unavailable for public business, [despite the fact that] there had always been a regular meeting of the Senate on this day....

✴built the Curia Julia (named in his honour) beside the Comitium ... ;

✴forbad any likeness of him to be carried at the funerals of his relatives, as if he were, in very truth, a god; and

✴decreed that no-one who took refuge in his [temple] in order to secure immunity should be driven or dragged away from there, a distinction which had never been granted to any god since the days of Romulus ...”, (‘Roman History’, 47: 18:4 - 19:3).

Lex Rufrena (42 BC ?)

An inscribed statue base (CIL VI 0872) from Ocriculum, which is now in the Sala Rotunda, Musei Vaticani, reads:

Divo Iulio iussu / populi Romani/ statutum est lege/ Rufrena

It records that the base supported a statue of divus Julius that had been erected by order of the Roman people in accordance with the lex Rufrena. The existence of two other similar inscriptions:

✴CIL I 2972, from Minturnae in Latium et Campania (now in the lapidarium of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Minturno); and

✴CIL IX 5136, from Interamna Praetuttiorum in Picenum (now in the church of San Pietro at Campli, near Teramoo, in the Abruzzo region);

suggests that this law required such cult statues to be erected across Italy. Stefan Weinstock (referenced below, at p.397, note 5) noted that Rufrenus, whom Cicero mentioned as serving under Lepidus in 43 BC, could have issued this law as Tribune of the Plebs (a post that he might have held in 42 BC), but this is far from certain.

Octavian’s First Battle against Sextus (October)

Sextus had escaped from the scene of Caesar’s famous victories over his father:

✴at Pharsalus, in modern Egypt) in 46 BC, after which his father had been killed; and

✴at Munda (in modern Spain) in 45 BC, the battle in which his older brother had been killed.

Sextus had remained in Spain and continued to cause problems for the Romans until 43 BC, when Lepidus, on behalf of the Senate, had persuaded him to withdraw with honour. Nevertheless, Octavian had proscribed him under the lex Pedia.

Appian described the events that led to his first confrontation with Octavian:

“When the triumvirate was established, [Sextus Pompeius] sailed to Sicily and, since Bithynicus, the governor, would not yield the island, he besieged it, until Hirtius and Fannius, (two men who had been proscribed and had fled to [Sextus] from Rome) persuaded Bithynicus to surrender Sicily to him. ... [He now] had:

✴ships;

✴an island lying convenient to Italy; and

✴an army, now of considerable size, composed of

•his own men;

•those who had fled from Rome, ...;

•those sent to him by the Italian cities that had been [selected by the triumvirs] as prizes of victory for [their] soldiers; and ...

•many seafaring men from Africa and Spain, skilled in naval affairs ...

When Octavian learned these facts he sent [his ally, Q. Salvidienus Rufus] with a fleet, as though it were an easy task to come alongside of [Sextus] and destroy him, while he himself passed through Italy with the intention of joining Salvidienus at Rhegium”, (’Civil Wars’, 4: 84: 5).

Appian then described the ensuing naval battle in which Sextus’ more experienced seamen had the better of the fighting:

“Salvidienus retired to the port of Balarus, ... where he repaired what was left of his damaged and wasted fleet. When Octavian arrived, he gave a solemn promise to the inhabitants of Rhegium and Vibo [two of the towns selected for veteran settlement, that they should now] be exempt from the [list], because he feared them on account of their nearness to the straits [of Messina]. As Antony had sent him a hasty summons, he set sail to join the latter at Brundusium ...”, (’Civil Wars’, 4: 85-6).

As Kathryn Welch (referenced below, 2012, at p. 179) pointed out, our surviving sources contain relatively little about Sextus’ victory over Salvidienus, but its importance:

“... must be [discerned] by noting [Octavian’s] route around Sicily. When he eventually set out to join [Mark Antony] (and it was many months before this was possible), he had to circumnavigate the island because the straits of Messina were closed to him.”

Mark Antony’s Victory at Philippi (October)

By late 42 BC, Cassius and Brutus had confiscated sufficient wealth from the unfortunate provincials in the east to buy the services of a large army made up principally from men who had fought under Caesar. This army was assemble at Philippi, on the coast of Macedonia.

Lepidus was left in Rome when Mark Antony and Octavian embarked with a joint force from Brundisium across the Adriatic to meet it. At the first battle (3rd October), Mark Antony defeated Cassius and stormed his camp, where Cassius, believing that Brutus had also been defeated, committed suicide. In fact, Brutus had defeated the army led by Octavian and had captured the camp of Mark Antony and Octavian. Octavian, who had not taken part in the battle, had fortunately left the camp in time: according to Plutarch:

“[Octavian], as he himself tells us in his [memoirs], barely succeeded in having himself carried forth [from the camp] following a vision... of his friend, Marcus Artorius, [in which he was told to] ... rise up from his bed and depart ... [His departure went unnoticed and] he was thought to have been slain; for his litter, when empty, was pierced by the javelins and spears of his enemies”, (’Life of Brutus’, 41:7-8).

Brutus, perhaps unwisely, offered battle again on 23rd October, was defeated and committed suicide.

Appian ended his account of the battles as follows:

“Thus did Octavian and [Mark] Antony, by perilous daring and by two infantry engagements, achieve an unprecedented success. Never before had such numerous and powerful Roman armies come in conflict with each other. ... Nor was there ever such fury and daring in war as here, when citizens contended against citizens, families against families, and fellow-soldiers against each other. The proof of this is that, taking both battles into the account, the number of the slain mong the victors appeared to be not fewer than among the vanquished. Thus the army of [Mark] Antony and Octavian confirmed the prediction of their generals, passing in one day and by one blow from extreme danger and famine and fear of destruction to lavish wealth, absolute security, and glorious victory. Moreover, the result that[Mark] Antony and Octavian had predicted as they advanced into battle came about: their form of government was chiefly decided by that day's work ...”, (’Civil Wars’, 4: 137-8).

Cassius Dio reached a similar conclusion:

“That this struggle ... surpassed all previous civil conflicts of the Romans would be naturally surmised ... now, as never before, liberty and popular government were the issues of the struggle; ... one side was trying to lead [the Romans] to autocracy, the other side to self-government. [Once the first side, led by Mark Antony and Octavian, had won], the [Romans] never again attained absolute freedom of speech, even though [they had been] vanquished by no foreign nation; ... [they] triumphed over and were vanquished by themselves, defeated themselves and were defeated, and consequently they exhausted the democratic element and strengthened the monarchical”, (’Roman History’, 47: 39).

In short, the Roman Republic had defeated itself.

After Philippi

As Cassius Dio pointed out, after the Battle of Philippi, almost all of Caesar’s assassins were either dead or shortly to die.

“As for [Mark Antony and Octavian], on the other hand, they secured an advantage over Lepidus for the moment, because he had not shared the victory with them; yet they were destined before long to turn against each other. For it is a difficult matter for three men, or even two, who are equal in rank and as a result of war have gained control over such vast interests, to be of one accord. ... Thus, they immediately redistributed the empire, so that:

✴Spain and Numidia [passed from Lepidus to Octavian]; and

✴Gaul and Africa [passed from Lepidus] to [Mark] Antony;

and they further agreed that, if Lepidus showed any vexation at this, they should give up Africa to him. This was all they allotted between them, since Sextus [Pompeius] was still occupying Sardinia and Sicily, and the other regions outside of Italy were still in a state of turmoil. ... So, they left Italy and the places held by Sextus as common property.

✴[Mark] Antony undertook to reduce those who had fought against them [in the east] and to collect the money [there] necessary to pay what had been promised to the soldiers; and

✴[Octavian] undertook:

•to curtail the power of Lepidus, if he should make any hostile move;

•to conduct the war against Sextus [Pompeius]; and

•to assign to those of their troops who had passed the age-limit the land which they had promised them.

... After making these agreements..., putting them in writing and sealing them, they exchanged copies , ... so that, if any transgression were committed, it might be proved by these records. Thereupon [Mark] Antony set out for Asia and [Octavian] for Italy”, (’Roman History’, 48: 1-2).

The situation facing Octavian when he returned to Rome was extremely fraught:

✴the proscriptions had taken their toll;

✴many of the towns and cities of Italy lived in dread of the confiscations that would be needed for the settlement of the veterans who had returned with Octavian;

✴these veterans were impatient and very hard to control; and

✴Sextus Pompeius was disrupting the supply of grain to Rome.

In addition, two supporters of Mark Antony, Lucius Antonius (his brother) and Servilius Isauricus, took office as the consuls of 41 BC, while Mark Antony’s wife and Octavian’s mother-in-law, the redoubtable Fulvia, pursued her own agenda.

Events of 41 - 40 BC

Consuls of 41 BC

Aureus (RRC 516/1, 41 BC) issued by Mark Antony to commemorate the appointment of L. Antonius as consul

Obverse: Legend: A͡N͡T·A͡VG·IMP·III·V·R·P·C: head of Mark Antony

Reverse: PIETAS·COS (a reference to L. Antonius, Mark Antony’s ‘pius’ brother)

Fortuna holding rudder in right hand and cornucopiae in left hand, with stork

The consuls appointed for 41 BC were L. Antonius, the brother of Mark Antony, and P. Servilius Vatia Isauricus (who, as we shall see, played little part in the momentous events of the year).

David Sear (referenced below, at p. 193) observed that four traditional moneyers held office in Rome:

“... during the troubled year of 41 BC, ... [but] the scarcity of their issues suggests only a brief period of activity, and this accords well with the situation in Italy, where Octavian was maintaining only a precarious hold on power ...”

However, as Michael Crawford (referenced below, at p. 742) observed, Mark Antony:

“... struck two issues [in the east], one in his own name and one in the names of a series of legates:

✴the first issue, [RRC 516], celebrates with the legend PIETAS COS the consulship of his brother ..., the reverse type changing from Fortuna (as in RRC 516/1, illustrated above) to Pietas; and

✴the second issue, [RRC 517], alternates the portrait of Octavian with that of L. Antonius, [while] the portrait of [Mark Antony himself] forms the constant obverse type.”

This situation suggests that Mark Antony remained the senior partner in the triumvirate, notwithstanding his absence from Rome.

Veteran Settlement

Appian recorded that, before Mark Antony, Lepidus and Octavian had returned to Rome from Bononia in late 43 BC, they had placated Caesar’s long-suffering veterans by announcing to them that:

“... 18 cities of Italy (cities which excelled in wealth, in the splendour of their estates and houses were to be given to them as colonies and divided among them (land, buildings, and all), just as though they had been captured from an enemy in war. The most renowned among these were Capua, Rhegium, Venusia, Beneventum, Nuceria, Ariminum, and Vibo. Thus were the most beautiful parts of Italy marked out for the soldiers.”, (’Civil Wars’, 4: 3).

Plancus’ epitaph (CIL X 6087, as above)recorded that agros divisit in Italia Beneventi (he distributed land in Benevento in Italy). He presumably did so in 41 BC, soon after Mark Antony’s victory at Philippi:

Veteran Settlement

Appian recorded that, before Mark Antony, Lepidus and Octavian had returned to Rome from Bononia, they had placated Caesar’s long-suffering veterans by announcing to them that:

“... 18 cities of Italy (cities which excelled in wealth, in the splendour of their estates and houses were to be given to them as colonies and divided among them (land, buildings, and all), just as though they had been captured from an enemy in war. The most renowned among these were Capua, Rhegium, Venusia, Beneventum, Nuceria, Ariminum, and Vibo. Thus were the most beautiful parts of Italy marked out for the soldiers.”, (’Civil Wars’, 4: 3).

As Laurence Keppie (referenced below, at p. 61) observed:

“The method of acquiring land was simple and callous: wholesale confiscation from owners [who were] mostly innocent of any disaffection or disloyalty [to the newly-elected triumvirs]. With good reason could the dispossessed complain of the injustice of their plight.”

Benevetum

Plancus’ epitaph (CIL X 6087, as above) recorded that agros divisit in Italia Beneventi (he distributed land in Beneventum in Italy). Laurence Keppie (referenced below, at p. 155 argued that this colonisation almost certainly took place in 41 BC, soon after Mark Antony’s victory at Philippi.

At Fulvia's urging, he sent aid Lucius Antonius in the Perusine war. He defeated one of Octavian's legions, but retreated to Spoletium (App. BC 5.33; cf. Vell. 2.74.2)

As Enrico Zuddas and Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, p. 58, note 13) pointed out:

“Within a year, the operation was almost complete, when the Perusine War broke out” (my translation).

Hispellum

Laurence Keppie (referenced below, at p. 63) deduced the probable identities of the 18 towns that had been earmarked for confiscation at Bononia in 43 BC. Crucially for our understanding of the Perusine War (below), Keppie’s list included Hispellum (Spello), for which he cited the last line of this passage by the poet Propertius.

“Ancient Umbria ... bore you [Propertius] ... Where misty Mevania (Bevagna) wets its hollow field and Lake Umber warms the summer waters, the ramparts of towering Asisium (Assisi) - made more famous by your genius - surge from [the hilltop]. You gathered bones that should not have been gathered so young - your father’s bones - and were yourself forced into modest quarters: for when countless bulls were [still] ploughing your fields, the dull measuring-rod [of the Roman land surveyors] took away [your] wealth” (Elegy 4:1, adapted from the translation by Vincent Katz, referenced below, at pp. 343-5).

It seems that land in the Valle Umbra that had belonged to the Propertius’ family had been confiscated for veteran settlement when Propertius himself was still a boy. According to Keppie (at pp. 178-9):

“... the misfortunes of the Propertii seem best associated with the foundation of the [colony of Hispellum], an event that may be confidently placed in 41 BC.”

Thus it seems that Propertius’ father had died during the confiscation of at least part of his land. Since the young Propertius had gathered his father’s bones, we might reasonably assume that he had died violently, perhaps when he had tried to obstruct the process of confiscation.

Keppie (at p. 178) also referred to what was probably a single male relative of Propertius (perhaps his maternal uncle) who was the subject of two other of his poems (Elegy 1: 21 and 22). This man seems to have escaped the siege of Perusia (below) but to have been killed by brigands before he could reach safety. As Keppie observed:

“The Propertii of Assisium, recently deprived of a substantial part of their property (or under threat of deprivation) are easily envisaged as supporters of ... [the rebels at] nearby Perusia.”

As we shall see below, the war at Perusia was not primarily a local revolt: rather Perusia and its surrounding territory (which included the lands of the Propertii) found itself (probably unexpectedly) at the centre of a civil war between Romans in late 41 BC. However, when Octavian’s Roman enemies took refuge in Perusia (as discussed below), the local support that they found in the Valle Umbra has to be viewed in the context of the confiscations of that year. Furthermore, the roots of this ‘anti-Roman’ sentiment went back beyond the latest outrage: Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 208) wrote memorably of the Perusine War that it had:

“... blended with an older feud and took on the colours of an ancient wrong. Political contests at Rome and the civil wars into which they degenerated had been fought at the expense of Italy [for decades]. Denied justice and liberty, Italy rose against Rome [as personified by Octavian] for the last time.”

Perusine War (41 - 40 BC)

Outbreak of War

It seems that many of the Italians who faced dispossession at the hands of Octavian looked to them for support and that they, in turn, were inclined to give it (perhaps in the interests of justice or, more probably, because they saw political advantage in so-doing). Mark Antony seems to have contrived to make his own position as ambiguous as possible. Thus, Lucius Antonius and Fulvia were drawn into an open war with Octavian without being able to rely for more that hesitant support on those of Mark Antony’s legions that were still in the west.

The opening phase of the war took place in Rome and then in southern Italy (and need not concern us). The first recorded signs of revolt in central Italy occurred at Nursia (Norcia) and at Sentinum, on the Adriatic coast. Thus, Cassius Dio:

“[Octavian] made an expedition against Nursia, among the Sabines, and routed the garrison encamped before it, but was repulsed from the city [itself] by Tisienus Gallus [an ally of Lucius Antonius]. Accordingly he went over into Umbria and laid siege to Sentinum, but failed to capture it. For Lucius meanwhile ... had suddenly marched against [Sentinum] himself, [and taken possession of it]. So, on ascertaining this, [Octavian] left Quintus Salvidienus Rufus to look after [sic !] the people of Sentinum, while he set out for Rome”, (‘Roman History’, 48: 13: 2-4).

While Octavian had been distracted by the revolt at Nursia, Lucius had consolidated his position in Rome. Cassius Dio continued:

“Now, when Lucius learned of [Octavian’s imminent return to Rome], he withdrew [from the city]..., having had a vote passed authorising him to leave ... in order to begin a war; ... Thus [Octavian] was received into the capital without striking a blow and, when he pursued Lucius and failed to capture him, he returned [to Rome] and kept a more careful watch over [it]. Meanwhile, [things went well for Octavian at Sentinum and at Nursia]:

✴[As] soon as [Octavian] had left Sentinum and C. Furnius, [whom Lucius had left as] the defender of the walls [there], had issued forth and pursued him a long distance, [Salvidienus] unexpectedly attacked the citizens inside and, capturing the town [for Octavian], plundered and burned it.

✴The inhabitants of Nursia [then] came to terms without having suffered any ill treatment. However, the Nursians, after burying those who had fallen in the battle ... with [Octavian], inscribed on their tombs that they had died contending for their liberty. They were punished by an enormous fine, so that they abandoned their city and ... all their territory”, (‘Roman History’, 48: 13: 5-6).

These were but two of a number of skirmishes that must have taken place in this febrile period. They give a clear indication of the level of unrest that the confiscations (or perhaps the fear of further confiscations) had engendered, and the role that Lucius played in fanning the flames.

Siege of Perusia

According to Cassius Dio, as Octavian approached Rome:

“... Lucius withdrew from [the city], as I have stated, and set out for Gaul, [where he presumably hoped to join his brother’s legions, led by P. Ventidius Bassus and C. Asinius Pollio]; but, finding his way blocked [by Octavian’s army], he turned aside to Perusia, an Etruscan city. There, he was intercepted first by the lieutenants of [Octavian] and later by [Octavian] himself, and was besieged”, (’Roman History’, 48: 14: 1).

Cassius Dio then briefly summarised the war itself:

“The investment [of Perusia] proved a long operation, since the place is naturally a strong one and had been amply stocked with provisions. Horsemen whom Lucius had sent before he was entirely hemmed-in greatly harassed the besiegers and many others also came speedily to his defence from various quarters. Many attacks were made upon these reinforcements separately and many engagements were fought close to the walls, until the followers of Lucius, even though they were generally successful, nevertheless were forced by hunger to capitulate.” (‘Roman History’, 48: 14: 2-3).

Appian gave a more detailed account, which included events that touched on other Umbrian cities, including Spoletium (Spoleto) and Fulginia (Foligno):

✴“Octavian ... drew a line of palisade and ditch around Perusia 56 stades in circuit, on account of the hill on which it was situated; he also extended long arms to the Tiber, so that nothing might be introduced into the place. Lucius, for his part, built a similar line of contravallation, thus fortifying the foot of the hill. Fulvia urged Ventidius, Asinius, Ateius and Calenus to hasten from Gaul to the assistance of Lucius, and collected reinforcements [from Southern Italy], which she sent to Lucius under the command of [L. Munatius Plancus]. Plancus destroyed one of Octavian's legions, which was on the march to Rome”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 33).

✴“While Asinius and Ventidius were proceeding ... to the relief of Lucius, ... Octavian and Agrippa, leaving a guard at Perusia, threw themselves in the way. [Asinius and Ventidius] retreated: Asinius to Ravenna; and Ventidius to Ariminum [Rimini]. Plancus took refuge in Spoletium. Octavian stationed a force in front of each, to prevent them from forming a junction, and returned to Perusia, where he speedily strengthened [the siege]”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 33).

✴“When the work of Octavian was finished, famine fastened upon Lucius [in Perusia], and the evil grew more pressing ... Knowing this fact, Octavian kept the most vigilant watch. On the day preceding the Calends of January, Lucius thought to avail himself of the holiday, in the belief that the enemy would be off their guard, and to make a sally by night against their gates, hoping to break through them and bring in his other forces ... But the legion was lying in wait nearby, and ... Lucius ... was driven back ...”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 34).

✴“Ventidius and his officers, ashamed to look on while Lucius was starving, [finally] moved to his support, intending to overpower [the besieging army]. Agrippa and Salvidienus went to meet them with still larger forces. Fearing lest they should be surrounded, they diverted to the stronghold of Fulginium, 160 stades from Perusia. There Agrippa besieged them, [although they were able to light] many fires as signals to Lucius”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 35).

✴“[The men under siege at] Perusia rejoiced when they saw the fires, but, ... when the fires ceased, they thought that [Ventidius’ army] had been destroyed. Lucius, oppressed by hunger, again fought a night battle ... ; but he failed and was driven back into Perusia. There he took an account of the remaining provisions, forbade the giving of any to the slaves and prohibited them from escaping, lest the enemy should gain better knowledge of his desperate situation ...”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 35).

✴“As no end of the famine or of the deaths could be discerned, the [besieged] soldiers became restive ... and implored Lucius to make another attempt [to break out of Perusia] ... Lucius marched out at dawn ...”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 36).

✴[After heavy fighting, during which Octavian was able to call up fresh reserves], Lucius ... sounded a retreat. Then Octavian’s troops joyfully clashed their arms as for a victory, whereupon [Lucius’ men defiantly returned to the fight]. Lucius ran among them and besought them to sacrifice their lives no longer, and led them back groaning and reluctant. This was the end of this hotly contested siege ...”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 37-8).

For whatever reason, Octavian allowed Lucius and his army to withdraw from Perusia (although, as set out below) the civilians in the besieged city were less fortunate.

These events effectively brought the war to an end. Thus, according to Cassius Dio:

“After the capture of Perusia in the consulship of Cnaeus Calvinus (who was serving for the second time) and Asinius Pollio [i.e. in 4o BC], the other places in Italy also went over to [Octavian], partly as the result of force and partly of their own accord”, (’Roman History’, 48:15).

Reprisals

It seems that Octavian dealt harshly with the leaders of the rebellious Perusians. Thus, according to Appian:

“He then commanded the Perusians, who stretched out their hands to him from the walls, to come forward, all except their town council, and, as they presented themselves, he pardoned them; but the councillors were thrown into prison and soon afterwards put to death, except L. Aemilius, who had sat as a judge at Rome in the trial of the murderers of [Julius] Caesar, had voted openly for their condemnation and had advised all the other [judges] to do the same in order to expiate the guilt”, (‘Civil Wars’, 5: 48).

Although the ordinary citizens of Perusia apparently escaped execution, their suffering was not yet at an end:

“Octavian intended to turn Perusia itself over to the soldiers for plunder, but Cestius, one of the citizens, who was somewhat out of his mind ... set fire to his house and plunged into the flames. A strong wind fanned the conflagration and drove it over the whole of Perusia, which was entirely consumed, except the temple of Vulcan. Such was the end of Perusia, a city renowned for its antiquity and importance. It is said that it was one of the first 12 cities built by the Etruscans in Italy in olden time. For this reason, the worship of Juno had prevailed there, as among the Etruscans generally. But, thereafter, those [Peusians who survived the destruction of their city] took Vulcan for their tutelary deity instead of Juno”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 49).

Cassius Dio reported a higher death toll among the Perusians than Appian’s account suggests, and he implied that the fire in the city was the work of Octavian’s army:

“Of the people of Perusia and the others who were captured there, the majority lost their lives, and the city itself (except the temple of Vulcan and the statue of Juno) was entirely destroyed by fire. This statue, which was preserved by some chance, was brought to Rome, in accordance with a vision that [Octavian] saw in a dream, and it secured for [Perusia] the privilege of being peopled again by any who desired to settle there, though they did not acquire anything of its territory beyond the first mile”, (’Roman History’, 48:14).

The suggestion here seems to be that the cult statue of Juno, the old protector of Perusia, had been ritually ‘called’ to Rome in an ancient ceremony known as ‘evocatio deorum’. This vindictive act was presumably intended to replicate the evocation of the Etruscan god Voltumna to Rome after the fall of the Volsinii (Orvieto) in 264 BC. Cassius is our only source for the information that (at Juno’s behest) the Perusians were allowed to return to their ruined city (now protected by Vulcan), but that all their territory beyond a mile from its walls was confiscated.

The final direct casualties of the war were a number of eminent civilians from Rome who had apparently accompanied Lucius to Perusia. According to Appian:

“... Octavian made peace with all of them, but [his] soldiers [nevertheless persisted in attacking them and some were] killed. These were the chief personal enemies of Octavian, [who included] Cannutius, C. Flavius [and] Clodius Bithynicus ... . Such was the conclusion of the siege of Lucius in Perusia, and thus came to an end a war that had promised to be long-continued and most grievous to Italy”, (’Civil Wars’ 5: 49).

Two other authors gave more lurid accounts of these events, which they claimed had involved human sacrifice on an altar dedicated to divus Julius:

✴Cassius Dio:

“...most of the senators and knights [taken prisoner in Perusia] were put to death. And the story goes that they did not merely suffer death in an ordinary form, but were led to the altar consecrated to [divus Julius] and 300 knights and many senators were sacrificed there. They included Tiberius Cannutius, [despite the fact that], previously, during his tribuneship, he had assembled the [Roman] populace for [Octavian]”, (’Roman History’, 48: 14).

✴Suetonius:

“After the capture of Perusia, [Octavian] took vengeance on many, meeting all attempts to beg for pardon or to make excuses with the one reply: ‘You must die’. Some write that 300 men of both orders were selected from the prisoners of war and sacrificed on the Ides of March, like so many victims, at the altar raised to the deified Julius”, (’Life of Augustus’ 15: 1).

These two accounts differ in some details, which led Dominique Briquel (referenced below, at p. 42) to conclude that their respective authors:

“... had a common source, which they summarised differently” (my translation).

It is noteworthy that neither author had full confidence in this putative source, as evidenced by the phrases: ‘and the story goes that’ (Cassius Dio); and ‘some write that’ (Suetonius).

How likely is it then that these accounts of human sacrifice were true? Many scholars have agreed with Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 211), who believed that, while there had been executions at Perusia:

“These judicial murders were [subsequently] magnified by defamation and credulity into a hecatomb [mass sacrifice] of 300 Roman senators and knights in solemn and religious ceremony on the Ides of March before an altar dedicated to divus Julius.”

However, Octavian certainly portrayed this war as one of vengeance for the assassination of Caesar, and it is clear that his army also saw it in that way:

✴famously, two of the 48 sling shots recovered from the site (CIL XI 6721, numbers 45 and 46 in this entry in the EDR database) that were fired by Legio XI were inscribed: ‘div(om) Iul(ium)’; and

✴as noted above, Appian reported L. Aemilius, alone among the councillors of Perusia, was spared execution because he:

“... had sat as a judge at Rome in the trial [in absentia] of the murderers of [Julius] Caesar, had voted openly for their condemnation, and had advised all the other [judges] to do the same in order to expiate the guilt [presumably with the blood of the convicted assassins, should they be captured]”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 48).

Furthermore, as noted above, Cassius Dio recorded that the men who were allegedly sacrificed on the altar of divus Julius included:

“... Tiberius Cannutius, [despite the fact that] previously, during his tribuneship, he had assembled the [Roman] populace for [Octavian against Mark Antony]”, (’Roman History’, 48:14).

However, Cannutius’ actions at this assembly (which had taken place in November 44 BC) had been motivated, not by his esteem for Octavian. but by his detestation of Mark Antony. One wonders whether Cannutius had been among the tribunes who had prevented Octavian from exhibiting Caesar’s golden chair and his crown at the theatre earlier in the year (as discussed in my page on divus Julius)? This is at least possible and, if so, Cannutius might have paid for this denial of one of Caesar’s divine honours with his life.

In the light of this atmosphere of vengeance, some scholars have perceived at least an element of truth in the accounts of human sacrifice at the altar of divus Julius. Thus:

✴James Smith Reid (referenced below, search on ‘dragged’):

“If mock sacrifice [of at least some of the Roman prisoners at Perusia] really took place, it was [probably] the work [of Octavian’s soldiers, as Appian (above) had claimed]. They may have dragged victims before the altar of Caesar. Their ardent desire to avenge him is attested by some of the sling bullets discovered on the site, ... [which] were ... inscribed ‘divom Iulium’.”

✴Stefan Weinstock (referenced below, at pp. 398-9):

“After the surrender [at Perusia, Octavian] slaughtered many senators and knights, but certainly not as many as 300, at the altar of divus Julius on 15th March 40 BC. [Weinstock then set out series of historical precedents that demonstrated, to his satisfaction, that] the incident at Perusia was not isolated.”

✴Jonathan Warner (referenced below, at pp. 8-9):

“In a final assessment, the agreement of Suetonius and Dio, along with the confusion and bias of ... Appian, suggests that some form of human sacrifice took place at the fall of Perusia. ... Given the likelihood that this extraordinary event happened, it has some important implications for our understanding of Roman culture and history. The elements of human sacrifice found in Roman myths and rituals suggest, for example, that the practice was not completely alien. Moreover, the ordeal and stress of civil war makes human sacrifice plausible as an act of vengeance and pietas [i.e. in recognition of the vengeance owed to Julius Caesar]. Octavian’s human sacrifice was not simply a barbaric act of impiety. Rather, it speaks to the complexity of Roman religion, a system that, at times, could rationalise extremely violent acts.”

✴Zsuzsanna Várhelyi, referenced below, p. 137) observed that:

“Syme [as quoted above] thought that these were primarily judicial murders, which the anti-[Octavian] propaganda enlarged into a sacrificial scene. While that judicial aspect was likely present as a possible interpretation of events, to my mind the parallel between these post-siege murders and the divine references on the sling bullets [see above] suggests that a religious interpretation of the conflict should also be considered as a context in which to read this horrible event.”

Whatever the truth, the allegation that Octavian had engaged in human sacrifice was certainly widely believed and long-remembered. Thus, when Seneca the Younger wrote for the young Emperor Nero in ca. 50 AD, he observed that the characteristic clemency of Octavian/ Augustus had developed:

“ ... only after the sea at Actium had been stained with Roman blood [in 31 BC], only after both his own and his enemy’s fleets had been shattered off Sicily [in 36 BC], only after the arae Perusinae [altars of Perugia in 41 BC] and the proscriptions [of 43 BC]”, (’de Clementia’, 1:11; slightly adapted from the translation by Zsuzsanna Várhelyi, referenced below, p. 137).

Thus, even after a century or more, the horror of these allegations could be invoked in only two words: ‘arae Perusinae’.

Peace of Brundisium (early October 40 BC)

In the summer of 40 BC, Mark Antony appeared off the coast of Brundisium at the head of a substantial fleet. When Octavian’s men prevented his landing there, he moved further along the coast and then laid siege to the city. He also negotiated an alliance with Sextus Pompeius. However, as Octavian approached with a substantial army, and as both men realised that their respective armies would probably not fight each other, they settled their differences by negotiation. According to Plutarch, during their meeting:

“... Antony..., as a favour to [Octavian], was appointed to the priesthood of [divus Julius]: [Mark Antony and Octavian] transacted everything else also of the most important political nature ... in a friendly spirit” (‘Life of Mark Antony’, 33:1).

The so-called Peace of Brundisium was sealed by the betrothal of Mark Antony to Octavian’s sister, Octavia.: first husband, C. Claudius Marcellus (cos 50 BC) had died in May 40 BC, and she became the fourth wife of Mark Antony (after Fulvia’s recent death) in October. (Mark Antony had had his first, brief affair with Cleopatra by this time, and their twins were born in Alexandria on 25th December 40 BC.)

Octavian now received Mark Antony’s Gallic provinces, making him master of the west, while Lepidus was left with Africa. The ovation that Octavian received soon after was recorded in the ‘Fasti Triumphales’ as:

Imp. Caesar Divi f. (C. f.) IIIvir r(ei) p(ublicae) c(onstituendae)

ovans an. DCCXIII quod pacem cum M. Antonio fecit'

Imperator Caesar, son of the god [Julius], triumvir for the regulation of the Republic

an ovation because he made peace with Mark Antony

According to Plutarch:

“After this settlement, Antony sent [his genera], Ventidius, on ahead into Asia to oppose the further progress of the Parthians. He himself, as a favour to [Octavian], was [finally !] appointed to the priesthood of the elder Caesar; they transacted together everything else of the most important political nature in a friendly spirit”, (‘Life of Mark Antony’, 33: 1).

Appian recorded the tasks that now fell to Octavian and Mark Antony, who:

“... made a fresh partition of the whole Roman empire between themselves (the boundary line being Scodra, a city of Illyria, which was supposed to be situated about midway up the Adriatic gulf)):

“All provinces and islands east of this place, as far as the river Euphrates, were to belong to Antony and all west of it to the ocean to Octavian. Lepidus was to govern Africa, inasmuch as Octavian had given it to him:

✴Octavian was to make war against Pompeius unless they should come to some agreement; and

✴[Mark] Antony was to make war against the Parthians to avenge their treachery toward Crassus”, (‘Civil Wars’, 5: 65).

Pact of Misenum (Summer 39 BC)

Infuriated by the Peace of Brundisium, from which he was excluded, Sextus Pompeius renewed his blockade of Italy. However, in 39 BC,the triumvirs negotiated this pact with him: he agreed to end the blockade and, in return, his control of Sicily and Sardinia was recognised and he acquired Corsica. He was promised a future augurate and consulship, and Octavian married his relative Scribonia. The exiles who had taken refuge with Pompeius (except those implicated in Caesar’s murder) were allowed to return to Rome and to recover a quarter of their confiscated property. This effectively marked the end of the proscriptions.

Coinage

(RRC 525/1: 40 BC)

As it happens, Octavian was commemorated as the son of divus Julius in a number of issues in the short period between the Perusine War and the Battle of Naulochus:

✴Coins of this type had been minted for the first time by Ti Sempronius Gracchus: RRC 525/1-4 and Q. Voconius Vitulus: RRC 526/1-4 in 40 BC, shortly after Octavian’s victory in the Perusine War.

✴The iconography made its second appearance in the coins from military mints in 38-7 BC, the period that witnessed a series of naval battles against Sextus Pompeius. These issues comprised:

•three by Agrippa as consul designate in 38 BC (RRC 534/1-3); and

•two by Octavian at about this time (RRC 535/1 -2), the first of which was represented in the thesaurus.

✴The iconography was used again in the military issue of 36 BC (RRC 540/1-2), at the time of Octavian’s eventual victory over Pompeius at Naulochus.

As David Sear (referenced below, at p. 192) observed:

“The bearded Octavian makes his final appearance [in RRC 540/1-2]. With the defeat of the last Pompeians [whose army included the last of the erstwhile adherents of Caesar’s assassins, Octavian] reverted to being clean-shaven, a sure sign that [Caesar’s murder] had at last been avenged ...”

We might therefore reasonably wonder why all 18 of the bronzes in the thesaurus belonged to only one of the five issues (i.e. RRC 535/1) from military mints in 38-7 BC.

Read more:

Mitchell H., “The Reputation of L. Munatius Plancus and the Idea of Serving the Times’”, in:

Osgood J., Morrel K. and Welch K. (editors), “The Alternative Augustan Age” K.,(2019) Oxford, at pp. 163-81

Welch K., “The Lex Pedia of 43 BCE and its Aftermath”, Hermathena, 196-7 (2014) 137-62

Welch K., “Magnus Pius: Sextus Pompeius and the Transformation of the Roman Republic”, (2012) Swansea

Cooley A., “Res Gestae Divi Augusti: Text, Translation and Commentary”, (2009) Cambridge

Lange C. H., “Res Publica Constituta: Actium, Apollo and the Accomplishment of the Triumviral Assignment”, (2009) Leiden and Boston

Sear D., “History and Coinage of the Roman Imperators 49-27 BC”, (1998) London

Watson A. J. M., “Maecenas’ Administration of Rome and Italy”, Akroterion, 39 (1994) 98-104

Gabba E., “Trasformazioni Politiche e Socio-Economiche dell' Umbria dopo il 'Bellum Perusinum'”, in:

Catanzaro G. and Santucci F. (editors), “Bimillenario della Morte di Properzio”, (1986) Assisi, pp. 95-104

Keppie L., “Colonisation and Veteran Settlement in Italy, 47–14 BC”, (1983) Rome

Crawford M., “Roman Republican Coinage”, (1974) Cambridge

Harris, W., “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

Syme R., “The Roman Revolution” (1939, latest edition 2002) Oxford

Return to Roman History (1st Century BC)