Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Fourth Dictator Year (302/1 BC)

Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)

Fourth Dictator Year (302/1 BC)

Introduction

The year that is conventionally designated at 302/1 BC was the last of the four so-called dictator years, a difficult concept that I discuss in my page on Dictator Years (334/3; 325/4; 310/9; and 302/1 BC): in summary:

✴A scholar who was working in the late Republic ‘corrected’ the annalistic record in order to resolve difficulties with the Roman calendar by inserting four fictitious years in which a dictator held office without consuls, Andrew Drummond (referenced below, 1978, at pp. 556-63), in his fundamental paper on the dictator years, suggested that the ‘guilty’ scholar was probably T. Pomponius Atticus, in a work published in 47 BC.

✴Although these fictitious years were recorded (for example) in the Augustan fasti Capitolini and fasti Triumphales, they were ignored by all of our surviving annalistic sources (including Livy).

I described Livy’s account of the events of this year in my page Between 2nd and 3rd Samnite Wars (304-299 BC): in this page, I consider how the ‘discovery of the dictator year of 301 BC might have affected Livy’s narrative.

Livy’s Chronology for 302/1 BC

As note above, the Augustan fasti recognised the four dictator yeas. In the period under discussion here:

✴For 302 BC:

•the fasti Capitolini recorded:

-Consuls: [M. Livius . .] Denter and [M. Aemilius L.f. L.n. Paullus] (completed from ‘History of Rome’, 10: 1: 7)

-Dictator: C. Junius Bubulcus Brutus; and

•the fasti Triumphales recorded that C. Junius Bubulcus Brutus triumphed as dictator over the Aequi.

✴For 301 BC:

•the fasti Capitolini recorded the there was a dictator [and master of horse, without any consuls] (completed from the entry for 309 BC):

-Dictator: [M. Valerius] Maximus [Corvus]; and

•the fasti Triumphales recorded that M. Valerius Corvus triumphed as dictator over the Etruscans and the Marsi.

I also noted above that Livy (who would have been aware of the antiquarian ‘discovery’ of this dictator year) he did not insert it into his account: instead, he assumed that all of the magistrates above had served in a single consular year (conventionally designated as 302/1 BC), in which:

✴M. Livius Denter and M. Aemilius Paullus served as consuls (‘History of Rome’, 10: 1: 7);

✴C. Junius Bubulcus Brutus was appointed as dictator to deal with the Aequi and triumphed over them, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 1: 8-9); and

✴M. Valerius Maximus Corvus was appointed as dictator to deal with:

•rebels at the Etruscan city of Arretium, who had ousted the ‘powerful house of the Cilnii’; and

•the Marsi, who were obstructing the foundation of a Roman colony on or near their territory (History of Rome’, 10: 3: 2-3).

After Valerius defeated the Marsi:

“The war was now turned against the Etruscans”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 3: 5-6).

Livy knew of two entirely different traditions regarding Valerius’ activities in Etruria:

✴He noted in a postscript to his preferred account that:

“Some of my sources claim that Etruria was pacified without any important battle being fought, simply through the settlement of the troubles in Arretium and the restoration of the Cilnii to popular favour”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 5: 13).

✴However, in his preferred account (discussed below), Valerius:

“... [broke] the power of the Etruscans ... for the second time., ... granted [them] a two years' truce, ... [and] returned in triumphal procession to Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 5: 12-3).

In other words, Livy accepted Valerius’ dictatorship but placed it in the year in which Livius and Aemilius were consuls (when Junius also served as dictator).

M. Valerius Corvus in 302/1 BC

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at pp. 46-7) argued that:

“Livy’s brief version [of Valerius’ Etruscan campaign] exposes his longer version as the product of annalistic elaboration and invention. ... Since the [Augustan fasti] make Valerius dictator in the dictator year 301 BC, ... it is conceivable that:

✴this long tale was invented at the same time as the dictator years; and

✴Livy’s narrative had been influenced by an account that, [like the fasti], recognised these [fictitious] years.

... [However, despite] the general inauthenticity of Livy’s longer narrative, some items in it could perhaps ... be reliable.”

In this section, I attempt to identify those parts of this longer account that are reasonably likely to be reliable.

Rebellion at Arretium

Both of Livy’s variants began with the information that one of the reasons for Valerius’ appointment as dictator was that rebels at Arretium had ousted the ‘powerful house of the Cilnii’, who presumably enjoyed Roman support. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 46) observed that:

“The authenticity of these references to the Cilnii has been questioned, on the grounds that he fame of Maecenas in Livy’s own generation [arguably] led to a gratuitous insertion of the clan into [this narrative. ... However], we know that the family was old, and there is no strong reason for suspicion.”

This is particularly the case since Livy had already recorded that, in 311 BC:

“... the whole of the cities of Etruria, with the exception of Arretium, took up arms and began what proved to be a serious war by an attack on [the Roman colony of] Sutrium”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 32: 1).

In Livy’ shorter account (as we have seen), Valerius restored the Cilnii to power without the need for a battle. However, the longer version does not record that Valerius actually reached Arretium: all we know about his itinerary in this account is that:

✴he left his camp under the command of the master of horse while he returned to Rome to take the auspices afresh (‘History of Rome’, 10: 3: 7);

✴in his absence, the master of horse was defeated while foraging near this camp, which led to fears that Rome itself might be attacked (‘History of Rome’, 10: 4: 1);

✴by the time he returned, the camp had been moved back into a safer position (‘History of Rome’, 10: 4: 4);

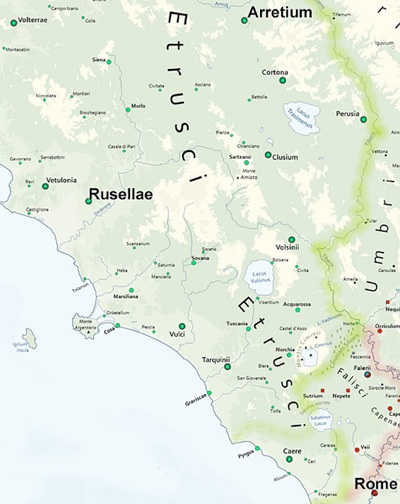

✴he moved it forward into the neighbourhood of Rusellae (‘History of Rome’, 10: 4: 6);

✴his legatus, Cn. Fulvius ( probably Cn. Fulvius Maximus Centumalus, the future consul of 298 BC - see Stephen Oakley, referenced below, at p. 75), who was in command of a Roman outpost, detected an Etruscan attempt to lure his men into an ambush at a nearby village (‘History of Rome’, 10: 4: 8);

✴when the ambush failed, Fulvius attacked the men who had been concealed and found himself confronting ‘the Etruscans, [who were] present in their full strength’ (‘History of Rome’, 10: 5: 4); but

✴he managed to keep his army in the field until Valerius arrived on the scene (‘History of Rome’, 10: 5: 4).

William Harris (referenced below, at p. 64) observed that:

“The mention of Rusellae [as the location for this battle] is surprising: [and]

✴a campaign [at Rusellae] seems too far from Arretium to be plausible in these circumstances; and

✴[Rusellae] is rather a long way to the north for a new Roman war with the Etruscans.

[However], arbitrary limits should not be set on Roman movements ...”

While Harris’ reluctance to reject Livy’s preferred scenario is understandable, it does seem odd that Livy himself failed to describe the circumstances in which so many Etruscan city states apparently combined to take up the cause of the rebels of Arretium by blocking the Romans’ advance on the city near Rusellae. I suggest below that:

✴Livy’s sources for Valerius’ putative intervention in the rebellion at Arretium and his putative victory at Rusellae were probably entirely separate;

✴he inserted his account of the victory at Rusellae after his first draft of the events of 302/1 BC (including the intervention at Arretium) at was complete; and

✴the apparent link between the two traditions was Livy’s own invention.

Battle Near Rusellae

In Livy’s account of the battle near Rusellae, Valerius’ direct involvement in it began as he responded to Fulvius’ appeals for support against ‘the Etruscans, [who were] present in their full strength’. As he advanced towards the fighting, he kept his cavalry to the rear and left a gap in the forward ranks of his infantry in order to facilitate an unexpected cavalry charge. At the appropriate moment:

“The [Roman] legions raised the battle cry and ... the cavalry charged [through the gap in their ranks]. The enemy were unprepared for such a hurricane, and a sudden panic set in. .... [The] result did not long remain in doubt. ... In this battle the power of the Etruscans was broken for the second time. ... [Valerius gave them] permission to send envoys to Rome to sue for peace: a regular treaty of peace was refused, but they were granted a two years' truce”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 5: 7-13).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 47) suggested that:

“The reference to the two-year [truce of 302/1 BC] is the detail [from Livy’s essentially inauthentic longer version] most likely to be sound ...”

Interestingly, in 299 BC, we find that:

✴the Etruscans decided to break their truce and prepare for war (‘History of Rome’, 10: 10: 5); and

✴after the death of the consul who had been sent to deal with this emergency:

“The Senate were prepared to order the nomination of a dictator but ... the leading patricians [demanded the election of a suffect consul instead. ... The man elected was] M. Valerius, the man whom the Senate had [originally] decided upon as dictator. The legions were at once ordered to Etruria. Their presence [checked the ambitions of] the Etruscans. ... Valerius devastated their fields and burnt their houses ... but he failed to bring [them] to battle”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 11: 4-6).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 48) pointed out that some scholars have suggested that Livy’s account of Valerius’ victory at Rusellae in 302/1 BC represented:

“... a retrojection of the campaign of M. Valerius in 299 BC.”

In this case, the breaking in 299 BC of the putative 2-tear truce of 301 BC would have been an invention. However, while this is possible, there is nothing to suggest that the fields and houses that Valerius destroyed in 299 BC were in or near Rusellae.

At the end of Livy’s longer account (and before he embarked on the shorter version), he recorded that Valerius:

“... returned in triumphal procession [from Rusellae] to Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 5: 13)

As noted above) the fasti Triumphales recorded that he triumphed as dictator (without consuls) in 301 BC over both the Etruscans and the Marsi. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at at p. 47) that:

“The report of the triumph of Valerius Corvus over the Etruscans in the fasti Triumphales proved only that [these fasti] were based on a source that also included this [claim], and not that the triumph itself is authentic. Nevertheless, it is not impossible ... that Valerius really did triumph triumph over both Marsi and Etruscans.”

His argument (if I have correctly understood it) was that, perhaps:

✴Valerius had been awarded a triumph for a military victory over the Marsi (paralleled by Junius’ triumph over the Aequi); and

✴his earlier diplomatic success in Etruria might have been included in his putative Marsian triumph.

He therefore suggested that:

“The absence of any [authentic] notice of a battle against the Etruscans [in 302/1 BC] might explain the inventions in Livy’s longer version.”

However, it seems to me that, if an authentic record of Valerius’ triumph over the Marsi existed (with or without an associated triumph over the Etruscans), it is hard to see why Livy ignored it.

M. Valerius Corvus in 302/1 BC: My Conclusions

It is now time to revisit the hypothesis of Stephen Oakley with which I began this section: that it is conceivable that Livy’s longer version of Valerius’ activity in Etruria in 302/1 BC came from a source had been invented at the same time as the dictator years. I suggested above that:

✴Livy’s sources for Valerius’ putative intervention in the rebellion at Arretium and his putative victory at Rusellae were probably entirely separate;

✴he inserted his account of the victory at Rusellae after his first draft of the events of 302/1 BC (including the intervention at Arretium) at was complete; and

✴the apparent link between the two traditions was Livy’s own invention.

I suggest here, more specifically, that:

✴Livy’s source for Valerius’ putative victory at Rusellae wrote this account to explain what Valerius achieved in his (fictitious) year as dictator without consuls in 301 BC; and

✴Livy inserted it into his earlier description of the events of 302 BC, between:

•“The war was now turned against the Etruscans”, ((‘History of Rome’, 10: 3: 6); and

•“[Some of my authorities aver that] Etruria was pacified without any important battle being fought, simply through the settlement of the troubles in Arretium and the restoration of the Cilnii to popular favour”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 5: 13).

I would also like to suggest that support for this can be found in the fact that:

✴in Livy’s account of a Roman victory at Lake Vadimonis in the dictator year 310/9 BC, a Roman commander whom he did not name. he claimed that:

“... for the first time, broke the might of the Etruscans ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 39: 11); and

✴in his account of Valerius’ victory at Rusellae in the dictator year 302/1 BC, he claimed that:

“... the power of the Etruscans was broken for the second time ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 5: 7-13).

Read more:

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume IV: Book X”, (2007) Oxford

Shackleton Bailey D. R. (translator), “Cicero: ‘Letters to Atticus’ (Volumes I-IV)”, (1999), Cambridge MA

Drummond A., “The Dictator Years”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 27:4 (1978), 550-72

Harris W. M., “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

Return to Rome in the Early Republic (509 - 241 BC)