Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Political Settlements in Etruria: from the

Fall of Veii (396 BC) to the Destruction of Volsinii (265 BC)

Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Political Settlements in Etruria: from the

Fall of Veii (396 BC) to the Destruction of Volsinii (265 BC)

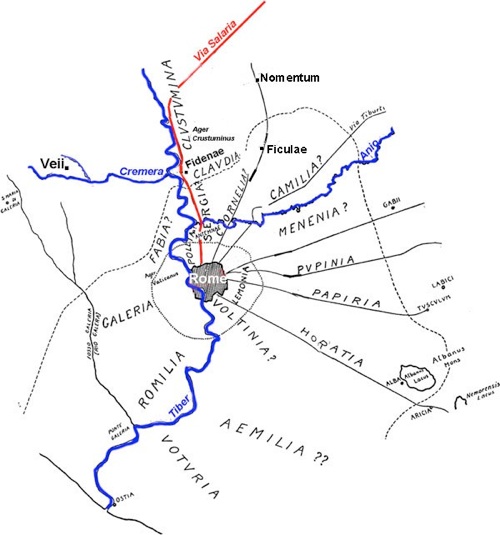

Roman Frontier with Veii (426 BC)

Seventeen Oldest Roman Tribes (G. C. Susini, 1959)

From Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, after p. 354)

Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 36) argued that the last of the original 17 rural tribes were probably the Claudia and the Clustumina, and that they had probably been established in ca. 495 BC Thus, in 426 BC, when the Romans finally wrested control of Fidenae from Veii:

✴three rural tribes had been established on the left bank of the Tiber to the north of its confluence with the Anio:

•the Sergia;

•the Claudia; and

•the Clustumina; and

✴the Fabia had been established on the opposite bank of this stretch of the river.

Ross Taylor observed (at p. 37) that:

“When Fidenae was captured and destroyed in 426 BC, its territory was apparently added to the Claudia ...”

In other words, the Claudia was extended northwards in order to embrace the Roman citizens who settled on the land confiscated from Fidenae.

Settlement after the Fall of Veii (396 - 383 BC)

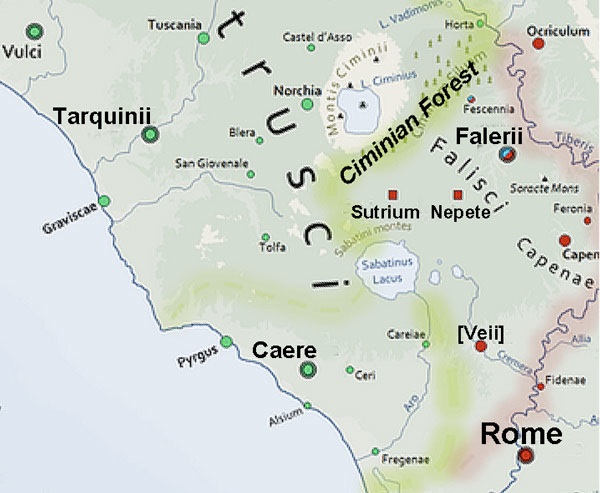

Likely locations of the new voting districts of 387 BC (Tromentina, Arnensis, Sabatina, Stellatina)

After Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, second end map)

Red squares = Colonies at Sutrium and Nepet (ca. 383 BC)

As Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, at pp. 298-9, entry 1) observed, when Veii fell into Roman hands in 396 BC, the whole of its territory was confiscated:

✴Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, 1960, at pp 47-8) noted that this confiscation increased the Roman territory by some 50%; and

✴Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 440) observed that it:

“... represented the largest increase to Roman territory in the history of the state.”

As Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, at p. 41) pointed out:

“After the conquest of Veii in 396 BC, there was, for the first time, a large quantity of ager publicus available to [the State].”

After taking Veii, the Romans attacked its allies Capena and Falerii, which surrendered in quick succession. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 347) observed that, although Livy’s account of the surrender of Falerii:

“... may be an exaggeration, Rome certainly [confiscated] land from Falerii upon which the Latin colonies of Nepete and Sutrium were later established [see below]. These operations gave [Rome] control of the area between the Tiber and the Ciminian Mountain ... .”

As we shall see, it seems likely that some of the territory of the Capenates passed into Roman hands at this point.

Livy described the viritane assignation of some of the newly-acquired territory in southern Etruria in 393 BC, when the Senate decreed:

“... that 7 iugera [about 4 acres] of Veientian territory should be allotted to each plebeian [in Rome who wanted it], and not only to the heads of families: account was taken of all the children in the house ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 30: 8).

According to Diodirus Siculus:

“... Romans portioned out in allotments the territory of the Veians, giving each holder 4 plethra [about an acre), but according to other accounts, 28”, (‘Library of History’, 14: 102: 4);

However, as we shall see, it is likely that only a small part of the newly acquired Roman ager publicus was actually allocated to settlers at this time, quite possibly because of the disruption caused by the Gallic invasion of Rome (in ca. 390 BC). According to Livy, in 389 BC:

“... those Veientians, Capenatians, and Faliscans that had [remained loyal to Rome] received citizenship and an allotment of land”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 4: 4).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at pp. 345) argued that, although Livy:

“... regarded this as a reward for those who had deserted to Rome, ... his notice [more probably indicated] the wholesale incorporation [into the Roman state] of the inhabitants of the conquered area”.

We might reasonably assume that, at this early date, the incorporated citizens would have had voting rights.

Creation of Four New Voting Districts (387 BC)

According to Livy, in 387 BC:

“Four tribes were added from the new citizens: the Stellatina; the Tromentina; the Sabatina; and the Arnensis; which took the number of [Roman voting] tribes to 25”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 5: 8).

This was the first occasion since 495 BC on which new tribes had been created, and we might reasonably assume that they were created for the Roman citizens that had acquired land that had belonged to Veii, Capena and Falerii before 389 BC.

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at pp. 440-1) observed that:

“The exact positions of [these] four tribes can be determined only approximately:

✴the Tromentina seems to have been on the site of Veii, since it was the tribe of the [much later] municipium Veiens ... ;

✴the Stellatina, later the tribe of Capena, must have been northeast, towards the Tiber;

✴the Arnensis, whose name may be derived from the ancient name for the river Arrone, lay to the northwest; and

✴[the Sabatina lay] to the north, adjoining the lake known in ancient times as the lacus Sabatinus ...”

See, also Daniel Gargola (referenced below, 2017, map 4, at p. 95). I have reflected this in the map above). The establishment of these four new tribes indicates that there were a number of new citizens in the areas in question. However, as Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, at p. 41) observed:

“There are many references [in the surviving sources continuing] availability of land in the area in periods long after the conquest of Veii, [which suggests that] the remaining amount of ager publicus [remaining after 387 BC] must ... have been great.”

Colonies Founded at Nepete and Sutrium (ca. 383 BC)

Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, pp. 298-9, entry 1) suggested that both colonies were established in 383 BC on land that had been confiscated from Vei in 396 BCi. However, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 347) argued that:

“... Rome certainly [confiscated] land from Falerii [in 394 BC]upon which the Latin colonies of Nepete and Sutrium were later established.”

He also argued that the precise timing of these foundations is uncertain, although he acknowledged (at p. 341) that they both took place in the early 4th century BC. Interestingly, the colonists had only Latin rights (and thus did not belong to a voting tribe. (When Nepete was enfranchised after the Social War, it was assigned to the Stellatina, although, for whatever reason, Sutrium was assigned to the Papiria (see Lily Ross taylor, referenced below, at p. 275 and p. 273 respectively).

Settlement after the Fall of Veii (396 - 383 BC): Conclusions

The effectiveness of this programme of:

✴the effective destruction of Veii and the confiscation of its erstwhile territory;

✴further land confiscations fro Capena and fakerii;

✴viritane settlement in a large tract of land that was assigned to four new voting tribes; and

✴the foundation of the strategically placed Latin colonies of Sutrium and Nepete;

is evidenced by the fact that there is no record of further hostilities between the Romans and the Etruscans until 358 BC.

Hostilities of the 358-1 BC

Livy recorded a series of confrontations in the 350s BC between Rome and an alliance of Tarquinii and Falerii, presumably caused by the Romans’ expansionary inclinations and their control over Sutrium and Nepete. As Hampus Olsson (referenced below, at p. 128) observed:

“Livy’s account of the events of the 350s BC between the Romans and the Tarquinienses has long been called into question by scholars. While there is a general agreement regarding the reliability of the basic outline of Livy’s narrative, there are several details that are in doubt: ....”

The most authentic components in his account are probably;

✴the triumph over the Etruscans awarded to C. Marcius Rutilus (the first plebeian dictator) in 356 BC, which was also recorded in the fasti Triumphales;

✴the intervention of Caere in 353 BC and their subsequent withdrawal, following which they were granted an indutiae for 100 years (see below); and

✴the end of hostilities with Tarquinii and Falerii in 351 BC, following which they were each granted an indutiae for 40 years (‘History of Rome’, 7: 22: 5).

As Olsson observed (at pp. 129-30):

“Livy treats the outcome of the hostilities as a Roman victory, but he does not report of any territorial gains on the part of the Romans; rather it seems that the war resulted in a [return to the] status quo, ... the true conquest of Etruria began a few decades later, ... [when] the truce between Rome and Tarquinii ended in 311 BC ... “

In Construction

Latin colonies: Nepete and Sutrium (383 BC); Cosa (273 BC); Heba ? (ca. 150 BC)

Maritime citizen colonies (ca. 264 - 245 BC): Castrum Novum; Pyrgi; Alsium; Fregenae

Citizen colony: Saturnia (183 BC); Graviscae (181 BC)

Prefectures listed by Festus: Caere ; Saturnia

Other prefectures: Forum Clodii (CIL XI 3310a, Pliny the Elder); Statonia (Vitruvius)

Underline indicates known or likely tribal assignation:

Tribes formed in 387 BC: Turquoise = Tromentina (Veii); Blue = Stellatina;

Red = Sabatina; Yellow = Arnensis (Blera and Ocriculum)

Green = Voltinia (old tribe)

Statonia has recently been located near Bomarzo, as shown on the map

The location that was previously assigned to it (between Vulci and Saturnia) is indicated in italics

Caere

Cassius Dio recorded that:

“The [people of Caere], when they learned that the Romans were disposed to make war on them, despatched envoys to Rome before any vote was taken and obtained peace upon surrendering half of their territory” (‘Roman History’, 10: fragment 33).

The tribe of Caere is usually deduced from a funerary inscription (known in two versions, CIL XI 3615 and 3257, that can be dated to the period 40-70 AD), which commemorates Titus Egnatius Rufus: the inscriptions were documented at Sutri in the 16th century, but Egnatius’ cursus included the post of dictator, an office that he almost certainly held at Caere. Early readings of the inscription had Egnatius assigned to the Voturia tribe (see, for example, Lily Ross Taylor, referenced below, at p. 276). However, there are two other inscriptions from Caere that suggest that this should be read as the Voltinia (one of the original 17 rural tribes):

✴an inscription (CIL XI 7613) from the Necropoli della Banditaccia commemorates Lucius Campatius of the Voltinia; and

✴an inscription (AE 2003, 0648) from Caere that commemorates a now-anonymous ‘L(ucius)’, who was assigned to the Voltinia.

Thus, we can reasonably assume that Egnatius was also assigned to the Voltinia, and that this was the tribal assignation of Caere from the time of its enfranchisement (which, as discussed below, possibly occurred after the Social War).

Forum Clodii

The tribe of Forum Clodii can be deduced from two inscriptions commemorating Quintus Cascellius Labeo:

✴an inscription (CIL XI 3303) from Forum Clodii, which is dated to 18 AD, reproduces a decree of the decurions in which it is noted that Cascellius had undertaken to finance in perpetuity a banquet on the birthday of the Emperor Tiberius; and

✴his epitaph (CIL VI 3510) from Rome gives his tribe as the Voltinia.

Other inscriptions from Forum Clodii that confirm this tribal assignation include: CIL XI 7556; AE 1992, 597; and AE 1992 598. As discussed below, Forum Clodii was almost certainly established on the Via Clodia for newly-settled Roman citizens,: they were presumably assigned to the Voltinia at the unknown date of settlement.

Coloniae Maritimae of 264-41 BC

There is epigraphic evidence that suggests that two of the citizen coloniae maritimae founded during the First Punic War (264-41 BC) were also assigned to the Voltinia:

✴An inscription (CIL VI 0951, dated to 97 AD) from Rome records Lucius Sertorius Evanthus, of the Voltinia, an aedile of a colony ‘C(---) N(---)’: this is usually completed as Castrum Novum and considered to be the Etruscan colonia maritima of this name.

✴Annarosa Gallo (referenced below, at p. 351 and note 36) referred to a recently-discovered fragmentary inscription from Alsium that records a now-anonymous member of the Voltinia.

The tribal assignations of the other two of these coloniae maritimae (Pyrgi and Fregenae) are unknown. However, most scholars (see, for example, Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, 2010, at pp. 315-6, entry 26) assume that all four were founded on land that had been confiscated from Caere.

Viritane Settlement on Land Confiscated from Caere: Discussion

Having analysed the evidence for the Voltinia in the area around Caere, Annarosa Gallo (referenced below, at pp. 351-2) put forward the hypothesis that:

“... the censors had progressively extended the tribe of the Roman citizens who were already settled on the ager publicus that had been confiscated [from Caere in 273 BC]” (my translation).

She also suggested that this extension of the Voltinia had encompassed not only the three centres above for which there is epigraphic evidence, but also Pyrgi and Fregenae (see her map at p. 343). On this model:

✴the putative viritane settlers on the land confiscated from Caere in ca. 280 BC were assigned to the Voltinia;

✴this assignation was given to the citizen colonists enrolled in the coloniae maritimae in 264-41 BC and to the citizen settlers at Forum Clodii (which, I suggest below, was constituted in the 2nd century BC); and

✴Caere itself was assigned to the Voltinia when it was enfranchised, which might not have occurred until after the Social War.

However, I doubt that there would have been much viritane settlement here during the Pyrrhic War (280-75 BC) and the First Punic War (264-41 BC): the Latin colony at Cosa had been founded to counter the growing naval threat from Carthage and this threat became manifest in the war that followed.

An alternative model might be suggested by looking at viritane settlement in three adjacent territories that were conquered in 290 BC but probably settled in ca. 270 BC: Sabina tiberina, the alta Sabina, and the territory of the Praetutti, on the Adriatic in southern Picenum. The developments here are discussed in by page on the ‘Settlement of the Sabine Lands’: in summary:

✴The main centres of Sabina tiberina, including Cures, were assigned to the Sergia, one of the original 17 rural tribes, presumably when they were given full Roman citizenship in 268 BC.

✴The other areas were assigned to one of two tribes that were formed only in 241 BC:

•The main centres of the alta Sabina (including Reate) were assigned to the Quirina.

•The Roman ‘new town’ of Interamnia Praetuttorum in the territory of the Praetuttii was assigned to the Velina.

Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 64) observed that these names “did not fit” the areas to

which they were assigned:

✴the Quirina, which (according to Festus) was named for Cures in Sabina tiberina, was assigned to Reate and the other centres of the alta Sabina; while

✴the Velina, which was named for the lacus Velinus , near Reate, was assigned to Picenum on the Adriatic, starting at Interamnia Praetuttorum.

She suggested (at pp. 64-5) that the names for the new tribes had been chosen by Curius Dentatus (who had conquered the territory and subsequently drained the lacus Velinus in order to facilitate its settlement) when he became censor in 272 BC. This putative plan would have been disrupted when Curius was forced to resign the censorship on the death of his colleague in mid-term. Curius himself died in 270 BC. Lily Ross Taylor (as above) suggested that:

“... the next censors, in 269-8 BC, made a different arrangement for Cures, placing it in the [existing tribe of the] Sergia. The [Quirina and the Velina existed only ‘on paper’] until the First Punic War was over.”

In other words, although the Quirina and the Velina had existed on paper since 272 BC, they had remained unassigned, first because of the death of Curius Dentatus and then because of the distraction of the First Punic War. On this model, the significant number of citizen settlers in the alta Sabina and the erstwhile territory of the Praetutti would have remained in their original tribes until 241 BC.

If we return now to the ager publicus near Caere, I argued above that:

✴the first significant influx of citizen settlement here probably comprised the 1,200 or so colonists that were enrolled at the four the coloniae maritimae during the First Punic War; and

✴the purpose of these colonies might well have included the facilitation/ nucleation of citizen settlement on the surrounding ager publicus after the war.

On the precedent of the Sabine lands, we might reasonably assume that they retained their original tribal allocations until 241 BC, when those at Castrum Novum (and possibly those at Pyrgi and Fregenae) were assigned to the Voltinia. If this is correct, then we might make minor changes to the model proposed by Annarosa Gallo (above):

✴the citizen colonists enrolled in the coloniae maritimae during the First Punic War retained their original tribes until the war was over, at which point they were assigned to the Voltinia;

✴the putative viritane settlers on the ager publicus near Caere and the citizen settlers at Forum Clodii were so-assigned thereafter; and

✴when Caere itself was enfranchised (which might not have occurred until after the Social War) it to was assigned to the Voltinia.

We know that both Caere and Forum Clodii were constituted as prefectures at some point: I argue below that the Roman prefects who had their seats here administered the legal affairs of this body of citizen settlers.

Tarquinii

According to Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 275), 8 of the 13 towns assigned to the Stellatina tribe (one of the four rural tribes organised in 387 BC after the fall of Veii) were in the Augustan seventh region:

✴Capena, possibly in 389 BC, when those Capenatians who had remained loyal to Rome during the Gallic sack of Rome were given full citizenship and received an allotment of land;

✴Graviscae, the citizen colony founded in 181 BC; and

✴six centres that were enfranchised after the Social War:

•Tarquinii;

•Tuscana;

•Ferntium;

•Horta;

•Nepet; and

•Cortona (which is not discussed here because it is some 150 km north of Tarquinii).

In addition, Statonia has recently been tentatively assigned to the Stellatina.

However, it seems likely that there was also a programme of viritane settlement of the coastal plain. It might be possible to develop this hypothesis by considering the subsequent tribal allocations of the area. Unfortunately, the tribe of the colony of Cosa is unknown. However:

✴Vulci and Tarquinii, which had both probably suffered land confiscation in ca, 280 BC, were later assigned to tribes that had been formed after the fall of Veii in 387 BC:

•Vulci was assigned to the Sabatina, as were: the prefecture/ colony of Saturnia (see below); and the colony of Heba (founded in ca. 150 BC); and

•Tarquinii was assigned to the Stellatina, as were: the colony of Graviscae, founded in 181 BC; and (probably, see below) the prefecture of Statonia.

✴Caere, together with: the prefecture of Forum Clodii and the maritime colonies of Castrum Novum, Pyrgi, Alsium, and Fregenae, was probably assigned to the Voltinia.

These tribal assignations, which are indicated in the map above, are sourced as follows:

✴Those centres assigned to the Sabatina and Stellatina (with the exception of that of Statonia) are taken William Harris (referenced below, at pp. 330-5).

✴The evidence for the likely assignation of Statonia to the Stellatina is discussed below.

✴So too are all the assignations to the Voltinia.

Vulci

According to Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 274) 4 of the 5 towns assigned to the Sabatina tribe (one of the four rural tribes organised in 387 BC after the fall of Veii) were in the Augustan seventh region:

✴the citizen colony Saturnia, founded in 183 BC; and

✴three centres that were enfranchised after the Social War:

•Vulci;

•Visentium (discussed below); and

•Volaterrae (which is not discussed here because it is some 180 km north of Vulci).

The only centre in her list that was in another regions was Mantua. William Harris (referenced below, at p. 332) suggested that Heba (also in the seventh region) might also have beem assigned to the Sabatina, since a now-lost funerary inscription (AE 1957, o219) from Heba, which dates to the period 200-330 AD commemorated:

C(aio) Petisio C(ai) f(ilio) Sab ...

The EDR database (see the AE link above) accepts the completion ‘Sabatina’, although (like Harris) it notes that Sab ... could alternative;y have been a cognomen. It seems to me that, given the concentration of the Sabatina in the seventh region, we can reasonably assume that this was, indeed the tribe at Heba.

Visentium

According to Debora Rossi (referenced below, at pp. 289-90):

“It used to be believed that the territory of Visentium, like most of the area to the west of Lake Bolsena, was on land expropriated from Vulci and reorganised in the first half of the 3rd century BC in a prefecture headed by Statonia. ... However, the recent proposal for the location of Statonia in the Tiber area gives rise to a different geopolitical scenario: [it now seems likely] that the Romans have left under the control of Vulci not only part of the territories between the [rivers] Arrone and Fiora, but also those towards on the western shore of of Lake Bolsena. That being the case, Visentium ... remained dependent on Vulci until it became a municipality: like other communities in the ancient territory of Vulci, it was assigned to the Sabatina tribe. It became a municipium {administered by duoviri, in the middle of the 1st century BC]” (my translation).

Prefecture of Caere (3rd century BC ?)

The Etruscan city of Caere appeared in Festus’ list of prefectures and also in his list of municipia (in a category that also included Aricia and Anagnia). Mario Torelli (referenced below, at p. 265) incorporated the suggestions of both Beloch and Sherwin-White into the traditional account of Caere’s early incorporation and postulated a simultaneous introduction of the prefecture:

“In 273 BC, Caere was the last south Etruscan city to be conquered [by Rome] .... Its [putative ancient] status as civitas sine suffragio was confirmed, but in a new, negative way ... The Romans confiscated half of the Caeretan land ... As a municipium, Caere lost its customary magistrates and was governed by a Roman prefect, who was responsible for justice in the city and throughout the former Caeretan territory. [This territory ?] was occupied by Roman viritane colonists and turned into a praefectura ...”

In fact, the surviving record of the revolt of 273 BC provides no evidence that, after the revolt, Caere:

✴was municipalised;

✴lost its customary magistrates; and/or

✴was constituted as a prefecture.

These assumptions are based only on information from Festus, who recorded only that Caere was constituted as both a municipium and a prefecture at some time prior to the early Augustan period.

Was Caere Incorporated before the Social War ?

According to Fabio Colivicchi (referenced below, at p. 195), recent excavations at Caere have unearthed evidence that:

“... its story ... after 273 BC is no less important than [in its former] splendour. The ancient sanctuaries of the Etruscan city ... were quite active and probably underwent significant renovations after the momentous date of 273 BC, possibly along with a large-scale urban renovation. This was a visible statement of prosperity and continuity of the community (albeit in politically renewed form) rather than of disruption. That the population of Caere was still clearly Etruscan in culture is confirmed by the continuity of funerary customs, ... and by the use of Etruscan as the standard language until the Social War, when the concession of full citizen rights, and therefore the requirement to enrol in a voting tribe, prompted the general adoption of Latin.”

Thus, there is apparently no archeological evidence for the Romanisation of Caere before the Social War. It is true that the ‘renewed’ political form of Caere mentioned by Colivicchi probably included the constitution of a prefecture, as indicated by Festus and suggested by other evidence (discussed below). However, as noted above, we cannot assume that it included the constitution of a municipium: as noted above, Festus is our only source for this information, and his source might well have relied on Strabo, whose testimony differs from that of Livy.

The next mention of Caere in the surviving sources relates to the events of in 205 BC, when Scipio Africanus assembled a fleet at his base at Sicily for an assault on Carthage: according to Livy:

“Scipio, though he could not obtain leave [from the Senate] to levy troops ... obtained leave to take with him such as volunteered their services; and also ... to receive what was furnished by the socii (allies) for building fresh ships. First, the states of Etruria engaged to assist the consuls to the utmost of their respective abilities. The people of Caere furnished corn and provisions of every description for the crews; the people of Populoni ... Tarquinii... Volaterrae ... Arretium ... Perusia, Clusium, and Rusella [also furnished supplies]”, (‘History of Rome’, 28: 45: 13-8).

Opinions vary as to the precise significance here of the term socii: for example, William Harris (referenced below, at p. 90), who assumed that Caere was a civitas sine suffragio at this time, did not see any problem with its inclusion in Livy’s list of Etruscan socii. However, it seems to me that this passage implies that Caere, like the other Etruscan city-states, still enjoyed nominal independence under Roman hegemony.

Edward Bispham (referenced below, at p. 462) included Caere in his list of centres that were municipalised in the Republican period, and cited Festus (at p. 466, note 22) in this context. However, he reasonably commented that:

“The history of the incorporation of Caere is opaque.”

It seems to me that this history was probably equally opaque to Festus’ source, who might have relied on Strabo (or another similar source), overlooking the contrary testimony of Livy. In other words, the surviving documentary evidence does not, in my view, allow us to conclude beyond doubt that Caere was a civitas sine suffragio prior to the Social War.

Prefecture at Caere

Robert Knapp (referenced below, at p. 32, note 68), who assumed that Caere was a civitas sine suffragio before the Social War, observed that:

“.... [this] status is not attested for [the following centres in Festus’ list of prefectures]; Venafrum; Allifae; Privernum; Frusino; Reate; and Nursia. As troublesome as this is, it appears reasonable to suppose these towns to be [civitates sine suffragio] on the basis of the attestation of that status for other towns in Festus' list.”

In other words, in his view, since six of the twelve prefectures in Festus’ list of non-Campanian prefectures are recorded as civitates sine suffragio, the other six must have shared this status. However, as Knapp recognised himself, this is ‘troublesome’. Indeed, given the doubts about the status of Caere, only five of Festus’ twelve non-Campanian prefectures are securely recorded as civitates sine suffragio before the Social War. Thus, it is at least possible that some of the other seven of these prefectures, including Caere, were constituted for a period as prefectures but not as municipia.

As noted above, Mario Torelli (referenced below, at p. 265) suggested that Caere was constituted as a prefecture in 273 BC. He found evidence to support this hypothesis in the form of the following graffiti, which was scratched on the wall of an underground complex at Caere:

C(aios) Genucio(s) Clousino(s), prai(? fectos)

He identified the subject as Caius Genucius Clepsina, the consul of 276 and 270 BC, and suggested (given these dates) that Genucius had also been Caere’s first Roman prefect in 273 BC. However, Christer Bruun (referenced below, at p. 275) was more circumspect:

“There is an on-going debate about what the official function of this Roman senator was at Caere [since the completion ‘praifectos’ is not completely secure]. He appears to be the C. Genucius Clepsina who was consul in 276 and 270 BC [although this again is not certain].”

Corey Brennan (referenced below, 2000, at p. 654) also had reservations:

“It is possible that C. Genusius, if really the consul [of the 270s BC], was sent to [Caere] as praetor in an earlier period of unrest. ... Alternatively, our C. Genusius [could be] a descendant of the consul of the 270s, to be placed later in (most likely) the 3rd century BC. ... In purely statistical terms, it is overwhelmingly probable that Genucius, whatever his exact date and identity, was a praefectus and not a praetor.”

In other words, the Genucius of the graffiti was probably a prefect, presumably at Caere, but he cannot be identified beyond doubt as the consul of 276 and 270 BC: thus the graffiti most probably supports Festus’ view that Caere was a prefecture, but it does not securely indicate that this prefecture was constituted in 273 BC.

There is other circumstantial evidence that suggests that the prefecture was constituted here in the 3rd century BC: according to Graham Mason (referenced below, at pp. 82-3), the four maritime colonies founded on the Etruscan coast (mentioned above and marked on the map above) were established on land that had been ceded by Caere in ca. 273 BC. Velleius Paterculus gave the foundation dates of three of these colonies:

“At the outbreak of the First Punic War [in 264 BC], Firmum [in Picenum] and Castrum [Novum] were occupied by colonies, ... Alsium seventeen years later [i.e. in 247 BC], and Fregenae two years later still”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 14: 8).

It is usually assumed that Pyrgi, like Castrum Novum, was founded in ca. 264 BC. We might reasonably assume that viritane citizen settlement also took place in this period on land that had been confiscated from Caere, and that this might have given rise to the constitution of a prefecture.

We might usefully explore this possibility by exploring the known tribal assignations in this area. The tribe of Caere is usually deduced from a funerary inscription (known in two versions, CIL XI 3615 and 3257), which can be dated to the period 40-70 AD and which commemorates Titus Egnatius Rufus: the inscriptions were documented at Sutri in the 16th century, but Egnatius’ cursus included the post of dictator, an office that he almost certainly held at Caere. Early readings of the inscription had Egnatius assigned to the Voturia tribe. However, there are two other inscriptions from Caere that suggest that this should be read as the Voltinia (one of the original 17 rural tribes):

✴an inscription from the Necropoli della Banditaccia commemorates Lucius Campatius of the Voltinia; and

✴an inscription discovered in 1970 and published by Lidio Gasperini (referenced below, 2003, at pp. 511-5) commemorates a now-anonymous ‘L(ucius)’, who was assigned to the Voltinia.

Thus, we can reasonably assume that Egnatius was also assigned to the Voltinia, and that this was the tribal assignation of Caere from the time of its enfranchisement. There is also epigraphic evidence that suggests the assignations of three nearby centres to the Voltinia:

✴An inscription (CIL VI 0951, dated to 97 AD) from Rome records Lucius Sertorius Evanthus of the Voltinia, an aedile of a colony ‘C(---) N(---)’, usually completed as Castrum Novum and attributed to the Etruscan maritime colony of this name.

✴Annarosa Gallo (referenced below, at p. 351 and note 36) referred to a recently-discovered fragmentary inscription from Alsium, another nearby maritime colony, that records a now-anonymous member of the Voltinia.

✴The tribe of the prefecture of Forum Clodii (below) can be deduced from two inscriptions commemorating Quintus Cascellius Labeo:

•an inscription (CIL XI 3303) from Forum Clodii, which is dated to 18 AD, reproduces a decree of the decurions in which it is noted that Cascellius had undertaken to finance in perpetuity a banquet on the birthday of the Emperor Tiberius; and

•his epitaph (CIL VI 3510) from Rome gives his tribe as the Voltinia.

I think that the ‘alternative hypothesis’ is more likely to be correct: the Voltinia was probably the tribe assigned (for whatever reason) to viritane settlers from Rome on land confiscated from Caere in 273 BC. On this model:

✴a prefecture would have been established at Caere as the seat of a prefect who administered the legal affairs of viritane and perhaps colonial citizen settlers, as soon as their numbers were sufficient to require this arrangement;

✴Caere itself would have been assigned to the Voltinia at the unknown date of its enfranchisement, which might well have post-dated the Social War.

Colonies in Etruria after the Conquest

Latin Colony at Cosa (273 BC)

Livy (‘Periochae’, 14) recorded the foundation of the colony of Cosa in 273 BC. We know that this was a Latin colony because Livy (‘Roman History’, 27: 9 - 27:10) included it among the 12 (out of 30) extant Latin colonies that did not refuse to meet their military obligations to Rome in 209 BC. (This was the only Latin colony in Etruria that was founded by the Romans after the latin War). Pliny the Elder’s account of the centres of this stretch of coast in the Augustan seventh region included:

“... Cosa of the Volcientes, founded by the Roman people ...”, (‘Natural History’, 3: 8)

This suggests that the colony was sited on virgin land that had been confiscated from Vulci, presumably in 279 BC: if so, then is our earliest record of the utilisation of the Etruscan territory that had been confiscated at around this time, according to Elizabeth Fentress and Phil Perkins (referenced below, at pp. 378-9):

“Cosa occupied a virgin site on a promontory between two fine natural harbours ... It dominates the coast from a hill rising some 110 m above the sea ... We do not know much about the initial colony ... Certainly its walls, in splendid polygonal masonry, were built in this period. These exploit the defences provided by the natural terrain of the hilltop, encircling 14 hectares ... .”

Unfortunately, two of the things that we do not know about the original colony are:

✴the number of colonists who were enrolled here; and

✴the size of the initial land allotments.

Edward Salmon (referenced below, at p. 38) pointed out that the number of initial colonists at those broadly contemporary Latin colonies for which the information is known is in the range 4,000-6,000. He noted that Cosa received 1,000 new colonists in 197 BC to replace numbers lost in the intervening period (see below) and suggested that this made the archeologists’ estimate of 2,500 original colonists seem low (since the need for reinforcement of 40 % seems excessive). He therefore suggested that the figure of 4,000 was perhaps more likely. He observed that:

“Whatever the original total, it seems likely that many of them lived on their [allotted land] holdings, perhaps miles away from Cosa [itself]. Its territory was large and could easily provide for them.”

Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, 2011, at paragraph 28) gave an interesting account of the way in which the colonists interacted with their local neighbours:

“Archaeological evidence suggests that a number of radical changes took place immediately after the conquest and the foundation of the colony [of Cosa]. Most of these point to an active attempt by the Romans to exclude local inhabitants from the colony, making it likely that, in this case, the traditional image of a Latin colony - with expulsion of local population to marginal areas - is accurate to some degree. The local inhabitants seem to have moved, on their own accord or by order of the Romans, to marginal areas. This is attested by the fact that some settlements located mainly to the north and east of the centuriated territory ( e.g. Telamon, Ghiaccioforte, and Poggio Semproniano) remained in use and even became larger, while new settlements emerged in these areas as well.”

The new colony might have protected the surrounding ager publicus. However, it was not optimally sited for this function, and no colonies were needed for this purpose on the land recently confiscated from Caere and Tarquinii. Furthermore, the location of Cosa strongly suggests an important role in maritime defence: as Edward Salmon (referenced below, at p. 79) observed:

“As the Pyrrhic War was drawing to a close, Carthaginian naval power [was becoming] menacing.”

Read more:

Olsson H., “Cultural and Socio-Political development in South Etruria. : The Biedano Region in the 5th to 1st Centuries BC”, (2021) thesis of the university of Lund

Fentress E. and Perkins P., “Cosa and the Ager Cosanus”, in

Cooley A. (editor), “Companion to Roman Italy”, (2016) Chichester

Torelli, M., “The Roman Period”, in:

Thomson De Grummond N. and Pieraccini L. (editors), “Caere”, (2016) AustinTX, at pp 263–70.

Bruun C. “Roman Government and Administration”, in:

Bruun C. and Edmondson J. (editors.), “The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy”, (2015) New York, at pp. 74-98

Colivicchi F., “After the Fall: Caere after 273 B.C.E.”, Etruscan Studies, 18:2 (2015) 178-99

Rossi D., “Il Territorio di Visentium in Età Romana”, in:

Di Nocera G. et al. (editors), “Archeologica e Memoria Storica: Atti delle Giornate di Studio (Viterbo 25-26 Marzo 2009)”, (2012) Viterbo, at pp. 289-310

Roselaar S., “Colonies and Processes of Integration in the Roman Republic”, Melanges de l'Ecole Francaise de Rome: Antiquite, 123:2 (2011) online

Gallo A., “M. Herennius M. f. Mae. Rufus (ILLRP 441) e la Tribù dei Coloni di Alsium”, in:

Silvestrini M. (editor), “Le Tribù Romane: Atti della XVIe Rencontre sur l’Épigraphie (Bari 8-10 Ottobre 2009)”, (2010) Bari, at 349-54

Roselaar S., “Public Land in the Roman Republic: A Social and Economic History of Ager Publicus in Italy, 396 - 89 BC”, (2010) Oxford

Bispham E., “From Asculum to Actium: The Municipalisation of Italy from the Social War to Augustus”, (2008) Oxford

Sisani S., “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

Sisani S., “Umbria Marche (Guide Archeologiche Laterza)”, (2006) Rome and Bari

Gasperini L., “Ancora sulla tribù Voltinia dei Ceriti”, in:

Corda A. M., (editor), “Cultus Splendore: Studi in Onore di Giovanna Sotgiu”, (2003) Cagliari

Brennan T. C., “The Praetorship in the Roman Republic”, (2000) Oxford

Mason G., “The Agrarian Role of Coloniae Maritimae: 338-241 BC”, Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 41:1 (1992) 75-87

Knapp R., “Festus 262 L and Praefecturae in Italy", Athenaeum, 58 (1980) 14-38

Harris W., “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

Salmon E, “Roman Colonisation under the Republic”, (1970) New York

Ross Taylor L., “The Voting Districts of the Roman Republic: The 35 Urban and Rural Tribes”, (1960) Rome

Return to Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)