Magna Graecia in the 4th Century BC (from Wikipedia)

The term Magna Graecia (literally, ‘Greater Greece’) is generally used to refer to those parts of peninsular Italy that were colonised by Greeks over a period from the 8th to the 4th centuries BC. These Greek-speaking coastal polities (which are often referred to as the ‘Italiotes’) shared southern Italy with Italian (mostly Oscan-speaking) tribes such as the Apuli, the Lucani, the Brutti, the Campani and (to the north) the Samnites. They also had cultural and political links with the Greek-speaking polities of Sicily and, to a lesser extent, with the Greek-speaking cities around the Mediterranean.

Tarentum

Arthur Eckstein (referenced below, at p. 147) observed that:

-

“Tarentum (Greek Taras) was founded in ca. 725BC, primarily by colonists from Sparta. It had the best harbour in southeastern Italy and a large, fertile hinterland.”

It was the only Greek city in Apulia, and was regularly attacked by its Italian neighbours: as Eckstein observed (at p. 148):

-

“One result [of this potential vulnerability] was that the Tarentium developed a policy (not unlike Rome) of placing new colonies at strategic defensive positions on indigenous land.”

One such colony was Heraclea, which the Tarentines had founded as a colony in 433 BC.

As Kathryn Lomas (referenced below at p. 31) observed, possibly from the late 6th century BC, the Greeks of southern Italy attempted:

-

“... to create some degree of unity ... [by adherence to an association of some kind] known to modern scholars as the Italiote League ...”

However, Dionysius I of Syracuse invaded southern Italy in the 390s BC and occupied a number of Italiote cities, including Croton. Tarentium (which might not have been a member of the league bat this time) seems to have escaped this invasion relatively unscathed. As Kathryn Lomas observed (at p. 33):

-

“The capture of Croton left the Italiote League without a hegemon, and it is probably at this point that Tarentim assumed the leadership of the league and transferred the treasury to Heraclea.”

Arthur Eckstein (referenced below, at p. 152) similarly observed, by the late 380s BC:

-

“The military power of Tarentum overawed [its other Greek neighbours] and made Tarentum [their] champion ... against the highland people who were threatening them [at this time] ...”

However, as we shall see, this did not mean that Tarentium was able to count of the subservience of the other league members

Arthur Eckstein (referenced below, at p. 152) observed that, in the decades that followed, the balance of power began to change in favour of the highlanders, until:

-

“The situation ... became so severe that the Tarentines called in warlords from European Greece for help:

-

✴first, King Archidamus III of Sparta (in 343 - 338 BC); and then

-

✴King Alexander of Epirus (336 - 331 BC).”

It will be useful to begin the discussion of the Romans’ conquest of the area with an account of the second of these ‘foreign’ interventions in peninsular Italy.

Alexander of Epirus in Italy (336 - 331 BC)

Map showing Epirus in relation to Macedonia and Molossia

From Wikipedia, my additions in red

Epirus is the name given to the territory in the northwest of ancient Greece that lay between Macedonia and the Ionian Sea. It was inhabited by a number of tribes, the most important of which (at least by the 4th century BC) were the Molossians, the Chaonians and the Thesprotians. As Elizabeth Meyer (referenced below, 2014, at p. 302) pointed out:

-

✴the Chaonians and the Thesprotians no longer had kings be the time of the Peloponnesian War (431-405 BC); but

-

✴Molossia was still a monarchy at this time and its kings controlled the sanctuary of Dodona (the oldest oracle in ancient Greece, and the second most prestigious pan-hellenic sanctuary of this kind after Delphi) until the monarchy ended in 232 BC.

Alexander’s Early Life (ca. 363 - 356 BC)

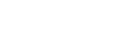

As indicated in the family tree above, Alexander was the son of Neoplotemus I of Molassia. The most important event in his life occurred in 357 BC, when his (probably older) sister, Olympias, married Philip II of Macedon in 357 BC. At this time, Neoplotemus was dead, and it was their uncle, King Arybbas, who arranged Olypias’ diplomatic marriage (since Philip was the enemy of his enemies, the Illyrians to the north). Olympias, who was probably Philip’s fifth wife (see below), probably improved her position at the (polygamous) Macedonian court, probably in the first year of the marriage, by giving birth to a son, Alexander, whom we know as Alexander the Great.

According to the obscure Pompeius Trogus (whose work, written in ca. 20 AD, is known to us only through the epitome of it that the equally obscure Justinus produced about a century later), at some point after his marriage to Olympias, Philip:

-

“... decided to depose Arrybas, king of Epirus (sic) ... and [therefore] invited Alexander... into Macedonia in [Olympias’] name ... When [Alexander] was 20, [Philip duly] took the kingdom [of Molossia] from Arrybas and gave it [him] ...”, (‘Epitome of Pompeius Trogus' Philippic Histories’, 8: 6).

I discuss Philip’s deposition of Arybbas below; for the moment, we should simply note that, as we shall see, it probably occurred in ca. 343 BC, when Alexander was probably about 20. It is therefore usually (and reasonably) assumed that:

-

✴he joined Olympias at the Macedonian court soon after her marriage;

-

✴he was educated and had received military training with other well-bred young men at court (some of whom, like Alexander himself, would have been the young relatives of Philip’s allies); and

-

✴by ca. 343 BC, he had convinced Philip that he would be capable of ruling Molossia in Arybbas’ stead.

Philip’s Deposition of Arybbas (ca. 343 BC)

Diodorus of Siculus recorded that, in either 346 or, more probably, 342/1 BC:

-

“... [Arybbas], king of the Molossians, died (sic) after a rule of ten years, leaving a son Aeacides ... , but Alexander, the brother of Olympias succeeded to the [Molossian] throne with the backing of Philip of Macedon”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 72: 1).

Arrybas was actually deposed on this occasion, but he did not die: instead, as Jessica Piccinini (referenced below, at pp. 471-2) pointed out, a surviving inscription indicates that, at this point, he:

-

“... renewed a long-established alliance [with the Athenians], reinforcing the pledge of mutual aid. The opening lines of the [relevant] decree contain explicit mention of previous citizenship honours granted by the Athenians to [two earlier] members of the Molossian royal family, Arybbas’ father and grandfather (that is to say, Alcetas I and Tharyps)... “

Thus, Arybbas’ dealings with Philip in 357 BC had represented a potential departure from his families traditional loyalties, which he reversed, for whatever reason, some 15 years later. The closing part of the Athenian inscription contains a threat that was clearly aimed primarily at Philip:

-

“... if anyone murders Arybbas, or any of the children of Arybbas, the penalties shall be the same as those that apply for other Athen citizens; and the [Athenian] generals in office shall ensure that Arybbas and his children recover their ancestral rule.”

Ian Worthington (referenced below, at pp. 116-7), who dated Alexander’s arrival at Philip’s court to 350 BC, suggested that, in 343 BC, when Philip’s relations with Athens were deteriorating:

-

“... Ayrbbas may have been taking steps to ensure the continuation of his rule [in Molossia by making] overtures to the Athenians ... At the best of times, Philip could not allow any form of insurrection to his south-west, but especially not now, with [his current peace agreement with Athens] looking shakier every day. Thus, [he] decided:

-

✴to invade Epirus [in order] to secure his south-western border once and for all; and

-

✴to stall any Athenian military support for Arybbas [by diplomatic means].”

It seems that his timing was impeccable:

-

✴he quickly deposed Arybbas in a bloodless campaign; and

-

✴although the Athenians provided Arybbas with a safe place of exile, they did nothing to implement their promise to use force on his behalf in order to recover his throne.

Adolfo Domínguez ((referenced below, 2015, at p. 112) pointed out that:

-

“In the [pseudo]-Demosthenes’ oration ‘‘On the Halonnesus’ (at 7: 32), written and perhaps delivered in 343/2 BC, the hostile actions carried out by Philip II ... are enumerated, among them that [he]:

-

‘... advanced with his army on Ambracia, razed and scorched the territory of the three poleis of Cassopaea: Pandosia, Boucheta and Elateia, colonies of the Eleans (sic.), and, [after] taking those cities by force, he handed them over to Alexander, his brother-in-law, to be his slaves’.

-

It is highly probable that this action took place at the same time as his [deposition of Arybbas] ...”

In an earlier paper, Domínguez (referenced below, 2014, at pp. 208-9) also noted that, from this time, Alexander:

-

“... controlled all the territory south of the middle and lower [stretches of the] Acheron river, including the northwestern coast of the Gulf of Ambracia up to the limits of Ambracia itself”, (my translation).

Adrian Goldsworthy (referenced below, at p. 190) observed that Philip’s specific:

-

“... aim was to secure Epirus’ border and to enrich [Alexander’s] kingdom, [since] these cities ... controlled the maritime trade to and from the wider world.”

In short, by his surprise attack on Arybbas’ territory and the coastal cities to the south of it, Philip:

-

✴improved the military value of the region between Macedonia and the sea as a bulwark against Ambracia and Athens; and

-

✴ensured that it was in the hands of a king on whom he could rely.

Alexander, King of Molossia (343 - 331 BC)

Ben Raynor (referenced below, 2017, at p. 255) observed that, in 343 BC, Alexander was now:

-

“... in a heady position. As a young king with important connections, he had received an education at the Macedonian court which had emphasised competition and athletic and military skills. He was backed by the strongest power on the Balkan peninsula and, thanks to Philip’s gift [of Pandosia, Boucheta and Elateia], controlled substantially more territory than any previous Molossian king, including a valuable outlet to the sea. More than anything else, he had grown up seeing from within the benefits that successful aggressive expansion under Philip II had brought to Macedonia. Inspired by the Macedonian experience of empire, Alexander I would prove hungry for conquest and glory himself.”

It is interesting to note that Alexander’s nephew, Alexander of Macedon (who was probably only about five years younger than he was) was also beginning to emerge as a figure in his own right at about this time:

-

✴a letter that he received from the ageing orator Isocrates in 342 BC suggests that he was considered to be Philip’s likely heir at that time, since his older brother, Arrhidaeus (see below) was incapacitated in some way; and

-

✴according to Plutarch:

-

“While Philip was making an expedition against Byzantium [in 340 BC], Alexander, though only 16 years of age, was left behind as regent in Macedonia and keeper of the royal seal,. During this time he subdued the rebellious Maedi and, after taking their city, drove out the Barbarians, settled a mixed population there and named the city Alexandropolis”, (‘Life of Alexander’, 9:1).

Battle of Chaeronea ( 338 BC) and its Aftermath

We know almost nothing about Alexander’s rule in Molossia before 337 BC, although it is entirely possible that he saw military service as Philip’s ally in the campaigns that had led to his victory over the Greeks. This campaign culminated in Philip’s victory over Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC:

-

✴both Diodorus Siculus, ‘Library of History’, 16: 86: 1) and Plutarch, ‘Life of Alexander’, 9:2-3) recorded that Philip’s son, Alexander of Macedon made an important contribution to this crucial victory; and

-

✴as Carl Roebuck (referenced below, at p. 75 and note 14) observed, Phillip’s allies at this time included:

-

“... Thessaly, Epirus (sic), and Aetolia ... Philip ... had established his brother-in-law, Alexander, as king in Epirus (sic), allowing [him] an extension of territory in Chaonia.”

Carl Roebuck (referenced below, at p. 83) also observed that, although most of the Greek cities that had been ranged against Philip escaped severe retribution:

-

“Corinth, [which had surrendered without offering resistance], had considerable strategic value as the gate-keeper of the Peloponnesus ... [It was therefore] singled out to house a Macedonian garrison, as Ambracia and Thebes had been.”

In relation to Ambracia, he noted (at p. 76 and notes 16 and 22) that:

-

“... Philip evidently considered that Ambracia was the key point for insuring his control over [western Greece]. It offered access to the Ionian Sea from Macedonia, and formed a wedge of territory between Epirus, Aetolia, and Acarnania, from which an eye might be kept on [these three territories]. Accordingly, in 343/2 BC, Philip had developed a claim through the convenient, if legendary, activity of his Heraclid ancestors and had made preparations to occupy the country. At that time, however, Athens had succeeded in preventing Philip's invasion by sending a force to Ambracia and gaining the support of Acarnania and the large islands in the Ionian Sea. After Chaeronea, Philip was in a position to make good his claim. A garrison was [duly] placed in Ambracia ... If Philip had already laid claim to Ambracia as part of his hereditary possessions, he might have administered the district through the garrison commander or, more probably, have depended on an oligarchy of his own adherents.”

Significantly, minting at Ambracia ended at this point, underlining the city’s loss of its independence. There is no evidence that Philip added Ambracia to Alexander’s territory: it probably remained part of Macedonia until 294 BC, when another Alexander, the son of the recently-deceased King Cassander of Macedonia, gave it to King Pyrrhus of Molossia/Epirus, who developed it as his capital.

Common Peace of the Greeks (337 BC)

Having established these strategically important outposts in Greece, Philip’s priority was to establish a ‘Common Peace’ across the region, in order to allow him to concentrate his military resources on a campaign in Asia. He therefore summoned all of the Greek states to Corinth in the winter of 338/7 BC, and ‘suggested’ that they should form a ‘Community of the Greeks’ (now usually known as the Corinthian League), the members of which would vow to refrain from harming:

-

✴any of the other members of the league; or

-

✴Philip himself and his descendants.

In spring 337 BC, Philip arranged a second meeting at Corinth at which he was ‘elected’ as hegemon of the league (albeit that he was not, formally, a member of it). As Ian Worthington (referenced below, at p. 163) observed, Philip:

-

“... had finally defeated the Athenians, rendered the Thebans impotent, stabilised the Peloponnese, neutralised the Spartans and crafted a ‘Common Peace’ that ... made Greece subservient to Macedonia ... [In short, he] had established an empire and, in so-doing, had created the first national state in the history of Europe.”

According to Diodorus, at this meeting, Philip had spoken:

-

“... about the war against Persia and, by raising great expectations, won over the representatives [of the Greeks to participate in it]. The Greeks elected him the general plenipotentiary of Greece, and he began accumulating supplies for the campaign. He prescribed the number of soldiers that each city should send for the joint effort, and then returned to Macedonia”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 89: 3).

As Philip prepared to leave for Asia, he probably considered Alexander’s Molossian kingdom and the Macedonian-held cities of Corinth and Ambracia as a buffer zone that would protect the southwestern border of Macedonia itself, should his arrangements under the ‘Common Peace’ break down during his absence.

Philip’s Last Marriage (337 BC)

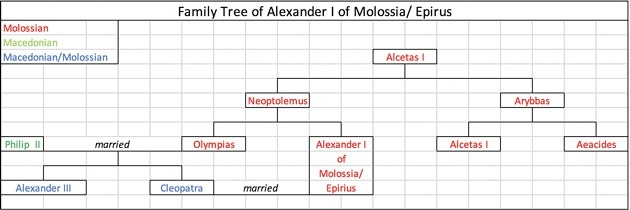

Yellow boxes = kings of Macedonia; Red = Molossian

Adapted from Wikiwand

According to Athenaeus (ca. 200 AD):

-

“Philip of Macedon did not ... take women along [when he went] to war: ... : rather, ... [he contracted diplomatic marriages that were relevant to his current wars]. Satyrus [see below], in his biography of [Philip], says:

-

‘In the 22 years he was king', he married:

-

✴Audata the Illyrian, who bore him a daughter, Cynna;

-

✴then Phila [of Elimeia in northern Macedonia], the sister of Derdas and Machatas;

-

✴then (since he wanted to appropriate the Thessalian people ... on grounds of kinship), he fathered children by two Thessalian women:

-

•... Nikesipolis of Pherae, who bore him [a daughter], Thessalonike; and

-

•... Philinna of Larissa, who bore him [a son], Arrhidaeus;

-

✴then, he acquired of kingdom of the Molossians ... by marrying Olympias, who bore him Alexander [the Great] and Cleopatra; and

-

✴then, when he conquered Thrace, Cothelas, the king of the Thracians, came over to him, bringing him his daughter Meda, ... [whom] he brought into his household besides Olympias;

-

✴then, in addition to all these, he married Cleopatra, the sister of Hippostratus and niece of Attalus, having fallen in love with her.

-

When he brought [Cleopatra] into his household beside Olympias, he threw his whole life into confusion. For, during the wedding celebrations, Attalus said:

-

‘Now, surely, there will be born for us true-bred kings, [rather than] bastards.’

-

When Alexander, [Philip’s son by Olympias], heard this, he threw [a cup, probably containing wine, at Attalus, who responded in kind]. After this:

-

✴Olympias fled to the Molossians; and

-

✴Alexander (fled) to the Illyrians.

-

Cleopatra bore Philip the daughter named Europa’”, (‘Deipnosophists’, 8: 557 b-e, translation from Adrian Tronson, referenced below, at pp. 119-20).

Troson pointed out (at p. 117) that Satyrus (knowns as ‘the Peripatetic’) probably wrote his biography of Philip in the late 3rd or early 2nd century century BC. He argued (at p. 125) that the information that Athenaeus had taken from Satyrus might well have been no more than:

-

“... a list of Philip’s wives and children, of a kind conventionally included in ancient biography, often as part of an obituary. ... Satyrus, as an early (if not, a primary) source might provide a chronologically reliable list of Philipp’s wives, as well as a reasonably accurate (though somewhat sensational) account of Macedonian court life.”

Thus, although scholars sometimes feel free to discount some of these marriages and/or re-order them in order to fit in with the chronology of Philip’s ‘diplomatic offensives’, there is actually no basis to dispute a list of this kind that was written only decades after Philip’s death. However, he cautioned that it was Athenaeus himself, rather than Satyrus, who was responsible for the theses that:

-

✴Philip’s first six marriages were all contracted for political reasons (see p. 120); and

-

✴he ‘threw his whole life into confusion’ by his seventh marriage, when, for the first time, he allowed love to influence his decision (see p. 123).

There is no reason to doubt that, during the celebration of Philip and Cleopatra’s marriage:

-

✴some sort of confrontation occurred between Philip’s son, Alexander, and Cleopatra’s guardian, Attalus; and

-

✴this caused Olympias and Alexander to leave Philip’s court.

It is also likely that Alexander of Molossia found his sister’s arrival at his court something of an embarrassment. It seems that Alexander of Macedon soon returned from his self-imposed exile.

However, for whatever reason, Philip found it expedient to arrange the marriage of Cleopatra (his daughter by Olympias) to her uncle, Alexander of Molossia: as Ian Worthington (referenced below, at 177) observed:

-

“The union would tie the two ruling houses even more closely together. ... [Alexander] accepted, and the marriage was scheduled ... for the ... summer of 336 BC.”

Philip‘s Preparations for the Invasion of Asia (336 BC)

According to Diodorus, shortly afterPhilip announced his forthcoming marriage to Cleopatra:

-

“... [he] opened the [pan-hellenic] war against Persia by sending Attalus and Parmenion into Asia [Minor] as an advance party, assigning tpart of his forces to them and ordering them to liberate the Greek cities [there]”, (‘Library of History’, 16: 91: 2).

Parmenion, as a long-standing commander in Philip’s army, was probably in overall command of this advance party. (As it happens, we know from a passage by Quintus Curtius Rufus (‘History of Alexander’, 6: 9: 17, translated by John Yardley, referenced below, at p. 137) that, at some point before he left for Asia, Attalus married a daughter of Parmenion).

Philip II appointed a general called Antipater to govern Macedon as his regent while he campaigned in Thrace. When Philip died in 336 BC, Antipater became an adviser to Alexander the Great, who set out for the East in 334 BC, leaving Antipater as both regent in Macedonia and strategos of Europe. Thus, Alexander of Epirus had little scope for independent action at home, and it is unsurprising that he apparently welcomed the Tarentine’s invitation to spread his wings in Magna Graeca. (From this point, the exploits of Alexander the Great no longer concern us, and I can therefore refer to Alexander of Epirus as ‘Alexander’).

Alexander’s Status in relation to Epirus

Ben Raynor (referenced below, 2017, at p. 255):

-

It is hardly credible that, between assuming the throne [of Molossia] in 343/2 BC and departing for Italy in 334 BC, Alexander I had not tried to build upon his initial strong position within Epirus itself.”

Adolfo Domínguez (referenced below, 2018, at p. 34):

-

“This period probably witnessed the creation of the much-disputed συμμαχία τῶν Ἀπειρωτᾶν, [(symmachy/alliance of the Epirotes) - SGDI 1336], whose origins and duration continue to give rise to multiple interpretations, but whose foundation in our opinion must correspond to the reign of Alexander . The strength of the Molossian State is witnessed by the fact that this [Alexander], without any fear about what he was leaving behind, could embark on an expedition to Italy, a venture that would end terribly for him but would lead to the ... succession to the throne of ... his [widow], Cleopatra ... .”

According to Livy:

-

“It seems that it was in this year [341 BC, sic] that Alexander, Epiri regem (King of Epirus), landed in Italy and [embarked on] a war that, had it prospered initially, would have undoubtedly have extended to Rome. This was about at the time of the exploits of Alexander the Great, the son of [Olympias], a man invincible in war, who was fated to die from disease while still a young mann, in another part of the world”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 3: 6-7).

We can discount Livy’s absolute chronology, although he is correct that both Alexanders left Greece at almost the same time:

-

✴as we shall see, Alexander the Great became King of Macedonia in 338 BC, crossed to Asia in 334 BC and died at Babylon in 323 BC; and

-

✴the Alexander whom Livy designated as king of Epirus almost certainly landed in Italy in 334 BC.

However, what concerns us here is whether Olympias’ brother, who was certainly the king of Molossia, was also, in any formal sense, the king of a wider polity known as Epirus.

It seems that Livy’s opinion that this was, indeed, his title was shared by the obscure Pompeius Trogus: in his epitome of Trogus, Justinus recorded that, countless generations after the foundation of the kingdom Epirus by the mythical Pyrrhus, the son of Achilles:

-

“The throne... passed in regular descent to Tharybas [i.e., Arybbas], ... [who had received his education in] Athens ... He was the first king to establish laws, a senate, annual magistrates and a regular form of government ... A son [sic] of this king was Neoptolemus, the father of:

-

✴Olympias, the mother of Alexander the Great; and

-

✴Alexander, who occupied the throne of Epirus after [Neoptolemus], and died in Italy in a war with the Bruttii”, (‘Epitome of Pompeius Trogus' Philippic Histories’, 17: 9-15).

However, no surviving Greek source refers to Alexander as basileus (king) of Epirus. Plutarch recorded that, by 297 BC:

-

“It was customary for the kings[of Molossia], after sacrificing to Zeus Areius at Passaron (a place in the Molossian land), to exchange solemn oaths with the Epirots:

-

✴the kings swearing to lead according to the laws; and

-

✴the people [presumably the Epirots] swearing to guard the kingdom according to the laws.

-

Accordingly, this was now done; both the kings, [Neoptolemus II (Alexander’s son) and Pyrrhus (the son of Alexander’s cousin)] were present, and associated with one another ... and many gifts were interchanged”, (‘Life of Pyrrhus’, 5: 2-3).

Thus, it seems that Plutarch believed that, by 297 BC, it was customary for the kings of Molossia to exercise sovereignty over ‘the Epirots’.

Ben Raynor (referenced below, 2017, at p. 253) discussed a series of bronze coins bearing the legend ΑΠΕΙΡΩΤΑΝ (“of the Epirotes, sometimes abbreviated as ΑΠ). He observed that, since this coinage is usually dated to ca. 330/325 BC, it has:

-

“... been seen as evidence of the emergence of a new Epirote state after Alexander’s death [in 331 BC]. However, an additional specimen of this series found during excavations at Cassope [has] strong stylistic links to mid-4th century coins of Syracuse and, particularly, to certain silver staters of Alexander I, [which has therefore been] dated to ca. 334 BC. The excavators argued for a date of ca. 342 BC and the accession of Alexander I for the beginning of this coinage. [Whether or not this precise date is accepted, the] find at least persuasively dates the start of the coinage ‹of the Epirotes› to before Alexanders death in 331/330 BC.”

He argued (at p. 256) that Alexander’s putative use on his coins:

-

“... of a term that had formerly been used to describe the wider area seems to express a claim to a sovereignty extending over the entire region. This was an ambitious claim but, thanks to Philip’s gift, Alexander was at least the first [Molossian] king whose subject territories extended significantly beyond Molossia. Besides, he would not be the only ruler in history to lay claim to a greater sovereignty than he had achieved as a declaration of aggressive intent.”

Adolfo Domínguez (referenced below, 2018, at p. 34) argued that:

-

“Epirus, which, [under Arybbas, had been] excessively pro-Athenian for Philip II’s liking, went on to be governed by a faithful ally and supporter of Macedonia, the young Alexander, Philip’s brother-in-law ... This period probably witnessed the creation of the much-disputed συμμαχία τῶν Ἀπειρωτᾶν, [(alliance of the Epirotes)], whose origins and duration continue to give rise to multiple interpretations, but whose foundation in our opinion must correspond to the reign of Alexander . The strength of the Molossian State is witnessed by the fact that this [Alexander], without any fear about what he was leaving behind, could embark on an expedition to Italy, a venture that would end terribly for him but would lead to the ... succession to the throne of ... his [widow], Cleopatra ... .”

José Pascual (referenced below), at pp. 63-5) argued that:

-

“The bringing together of the Epirote ethne under the [Molossian] dynasty, what we might call unification, was already a fact during the time of Pyrrhus, [who] is quite often referred to as the King of Epirus by ancient authors. ... However, we do not necessarily have to conclude that Pyrrhus was the unifier of Epirus, but rather that his kingdom could have been a terminus ante quem:

-

✴Cleopatra, [Alexander’s widow], who inherited the kingdom upon the [Alexander’s] death appears ... as the theorodoka for Epirus on the Argos list; and

-

✴Lycurgus (Leocr. 26) refers to her as Queen of Epirus.

-

All of this would point towards an already unified Epirus [by ca. 331-324 BC].”

Lycurgus of Athens (in a speech of 330 BC in which he attacked a fellow-citizen, Leocrates, who was accused of having deserted the city when it had fallen to Philipp II in 338 BC) claimed that the defendant had subsequently and illegally:

-

“... shipped corn, which had been bought from Cleopatra, from Epirus to Leucas and from there to Corinth”, (‘Against Leocrates’, 26).

This suggests that Cleopatra, Alexander’s widow, had represented Epirus in this transaction. Two surviving inscriptions from the same period similarly suggest her role as the representative of Epirus in pan-Hellenic matters:

-

✴SEG 9: 2, from Cyrene, lists shipments of grain from that region that were made during a period of famine in Greece:

-

“... to the Athenians, 100,000 medimnoi; to Olympias, 60,000 medimnoi; to the Argives, 50,000 medimnoi; to the Larissaeans, 50,000 medimnoi; to the Corinthians, 50,000 medimnoi; to Cleopatra, 50,000 medimnoi; ...”

-

This suggests that:

-

•Olympias was representing Alexander the Great in Macedonia during his absence; and

-

•Cleopatra was representing her young son, Neoptolemus II, presumably (given the size of her shipment) in Epirus rather than simply in Molossia;

-

✴SEG 23: 189 (see Milena Melfi and Jessica Piccinini, referenced below, at p. 54), which lists the theorodokoi ( the individuals responsible for receiving the theoroi of major sanctuaries when they visited to announce festivals and invite delegates) in northwestern Greece in the case of games held at Argos:

-

•Ambracia: Phorbadas

-

•Epirus: Cleopatra

-

•Fenice: Satyrinos, Pyladas, Karchax

-

•Kemara(?): Mnasalkidas (?) Aischron, son of fTeuthras

-

•Apollonia: Do[...]theos Orikos: [...]

-

•Corcira: nai[..]

-

As Melfi and Piccinini observed (at note 35):

-

“Cleopatra, the wife of Alexander, is the only woman attested in the [surviving] lists of Thearodokia. The fact that the queen is a single representative of Epirus suggests that the entire region was under the leadership of the Molossi (with the exception of Caonia, for which Fenice is mentioned separately)”, (my translation).

The view that Alexander exercised sovereignty over the whole of Epirus is not universally accepted: see for example, Elizabeth Meyer, referenced below, particularly at pp. 64-5 and p. 77). Furthermore, Ben Raynor (referenced below, 2019, at p. 326) subsequently presented what seems to me to be a more nuanced picture, in which he argued that, in the period ca. 340 - 232 BC:

-

“... the Molossians appear [in our surviving sources] acting as a group in a military capacity only as part of a larger Epirote army [except for one occasion in 323 BC, when they acted independently at a time] when regional cooperation was weak or had broken down. This suggests some division of competencies between different levels of organisation within the early Hellenistic Epirote state:

-

✴for matters of high politics and war, the Epirotes [apparently] acted together as a regional group led by the [Molossian] king; [while]

-

✴for other matters, including the quotidian exchanges of inter-community relations, the regional population groups (Molossians, Chaonians, Thesprotians, and others) acted independently.

-

Perhaps this was a natural compromise between:

-

✴the increasing need to band together for mutual defence following the rise of Macedon and other large hegemonic powers; and

-

✴the [natural] desire for individual communities in Epirus ... to maintain a sense of differentiation and independence.

-

Such a compromise could be sustained while [Molossian] kings acted as successful charismatic leaders around [whom] a regional military machine [could be built]. ... [However, after] the extinction of that line, survival required a fuller institutional elaboration of regional cooperation: so emerged the Epirote koinon after 232 BC.”

Alexander in Italy (334 - 331 BC)

Our surviving sources for Alexander’s wars in Italy are discursive and hard to disentangle:

Strabo recorded that:

-

“... the Tarantini were exceedingly powerful ... when they enjoyed a democratic government; for they not only had acquired the largest fleet of all peoples in that part of the world but were also able to muster an army of 30,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry, and 1,000 commanders of cavalry. ... But later, ... luxury prevailed to such an extent that they celebrated more annual public festivals than there were days in the year; and in consequence of this they also were poorly governed. One evidence of their bad policies is the fact that they employed foreign generals; for they sent for Archidamus, the son of Agesilaüs , Alexander the Molossian to lead them in their war against the Messapians and Leucanians, and, later on,[a number of others] ... . And yet, they could not give precedence to those whom they called in, and would [therefore] earn their enmity. At all events, it was out of enmity that Alexander:

-

✴tried to transfer the general festival assembly of all Greek peoples in that part of the world from Heracleia in Tarantine territory to Thurian territory; and

-

✴began to urge that a place for the meetings be fortified on the Acalandrus River.

-

Furthermore, it is said that the unhappy end that befell him was the result of their ingratitude”, (‘Geography’, 6: 3: 4)

Livy recorded that:

-

“The landing of Alexander of Epirus near Paestum, [Greek Poseidonia] led the Samnites to make common cause with the Lucanians, but he defeated their united forces in a pitched battle. He then pacem cum Romanis fecit (made peace with the Romans), but it is very doubtful how far he would have maintained them had his other enterprises been equally successful, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 17: 9-10).

He then used the occasion of Alexander’s death in Italy in 331 BC to look back on his Italian campaign:

-

“When he was invited by the Tarentines into Italy, he received a warning to beware of the water of Acheron and the city of Pandosia; for it was there that the limits of his destiny were fixed. This made him cross over into Italy all the sooner, so that he might be as far as possible from the city of Pandosia in Epirus and the river Acheron, which flows from Molossis into the ... Thesprotian Gulf. But, as often happens, in trying to avoid his fate he rushed upon it. He won many victories over the nationalities of Southern Italy:

-

✴inflicting numerous defeats upon the legions of Bruttium and Lucania;

-

✴capturing the city of Heraclea, a colony of settlers from Tarentum; and

-

✴taking:

-

•Potentia [and other cities] from the Lucanians;

-

•Sipontum from the Apulians;

-

•Consentia and Terina from the Bruttii; and

-

•other cities from the Messapians ... .

-

He sent 300 noble families[from these captured cities] to Epirus to be detained there as hostages”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 24: 2-5).

According to Pompeius Trogus, as epitomised by Justinus:

-

“Alexander, ... having been invited into Italy by the Tarentines (who desired his assistance against the Bruttians) had gone thither as eagerly as if, in a division of the world,

-

✴the east had fallen by lot to Alexander, the son of his sister Olympias,; and

-

✴the west to himself, [where he hoped to have as much] to do in Italy, Africa, and Sicily [as his cousin would have] in Asia and Persia.

-

On his arrival in Italy, his first contest was with the Apulians, ... [where] he soon concluded a peace and alliance with their king. ... He engaged also in war with the Bruttians and Lucanians, and captured several cities; and he formed foedus amicitiamque (treaties and alliances) with the Metapontines, the Poediculi, and Romans. But, when the Bruttians and Lucanians had collected reinforcements from their neighbours, they renewed the war with fresh vigour; Alexander was killed near the city Pandosia and the river Acheron, not knowing the name of this fatal place before he found himself in it ... The Thurians ransomed his body at the public expense and buried it”, (‘Epitome of Pompeius Trogus' ‘Philippic Histories’, 12: 2: 1-15).

Read more:

Goldsworthy A. J., “Philip and Alexander: Kings and Conquerors”, (2020) London

Domínguez A. J., “New Developments and Tradition in Epirus: The Creation of the Molossian State”, in:

Domínguez A. J. (editor), “Politics, Territory And Identity In Ancient Epirus”, (2018) Pisa, at pp. 1-42

Pascual J., “From the 5h Century to 167 BC: Reconstructing the History of Ancient Epirus”, in:

Domínguez A. J. (editor), “Politics, Territory And Identity In Ancient Epirus”, (2018) Pisa, at pp. 43-100

Domínguez A. J.,”’Phantom Eleans' in Southern Epirus”, Ancient West and East, 14, (2015) 111-43

Piccinini J., “Between Epirus and Sicily: An Athenian Honorary Decree for Alcetas, King of the Molossians?”, Archeologia Classica, 66 (2015) 467-79

Domínguez A. J., “Filipo II, Alejandro III de Macedonia y Alejandro I el Moloso: La Unidad de Acción de sus Políticas Expansionistas”, Polifemo, 14 (2014) 203-36

Meyer E,, “Molossia and Epeiros”, in:

Beck H. and Funke P. (editors), “Federalism in Greek Antiquity”, (2014) Cambridge, at pp. 297-318

Melfi M. and Piccinini J., “I Fonti”, in:

Perna R. and Çondi D. (editors), “Hadrianopolis II: Risultati delle Indagini Archeologiche (2005-2010)”, (2012), Bari, at pp. 51-65

Worthington I., “Philip II of Macedonia”, (2008) New Haven and London

Eckstein A. M., “Mediterranean Anarchy, Interstate War and the Rise of Rome”, (2006) Berkeley, Los Angeles and London

Lomas K., “Rome and the Western Greeks, 350 BC - 200 AD: Conquest and Acculturation in Southern Italy”, (1993) London

Tronson A., “Satyrus the Peripatetic and the Marriages of Philip II”, Journal of Hellenic Studies, 104 (1984) pp. 116-26

Yardley J. (translator) and Heckel (introduction and notes), “Quintus Curtius Rufus: History of Alexander”, (1984) London

Roebuck C., “Settlements of Philip II with the Greek States in 338 BC”, Classical Philology, 43:2 (1948) 73-92

Return to Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)