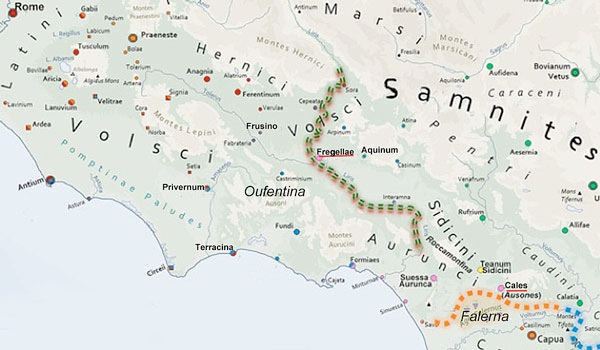

Underlined in red = Latin colonies founded in this period: Cales (336 BC) and Fregellae (328 BC)

War with the Sidicini (337 -332 BC)

Having secured their control over Latium and Campania in the Second Latin War (341-338 BC), the Romans now turned their attention to their potential unstable position in relation to the the strip of land between Campania and Samnium.

Events of 337 BC

The Sidicini and the Aurunci had been allied with the Latins and Campanians during the Latin War, and the fasti Triumphalis recorded that T. Manlius Imperiosus Torquatus was awarded triumph over the Latins, Campani, Sidicini and Aurunci in 340 BC. We hear no more about the Sidicini and the Aurunci until the consulship of C. Sulpicius Longus and P. Aelius Paetus (337 BC), when Livy recorded that:

-

“... a war broke out between the Sidicini and the Aurunci. Since the Aurunci had surrendered [to Rome] in the consulship of T. Manlius and had given no trouble since that time, they had the better right to expect assistance from the Romans”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 15: 1-2).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 572) observed that there is no reason to doubt that the Aurunci had surrendered in 340 BC, and that they had subsequently remained in the Roman sphere of influence. This passage by Livy suggests that, unlike the Aurunci, the Sidicini had not troubled to endear themselves to the Romans in 340-337 BC. The Senate therefore:

-

“... directed the consuls to defend the Aurunci. However, before they marched from Rome, news arrived that:

-

✴the Aurunci had abandoned their [original city on the Monte Roccamonfina] and ... taken refuge ... in [a new city, Suessa Aurunca] ..., which they had fortified; and

-

✴the Sidicini had destroyed the original city of the Aurunci , together with its ancient walls”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 15: 1-5).

Since the Aurunci were now safely ensconced in Suessa Aurunca, the consuls decided not to march against the Sidicini.

According to Livy, this failure to take action:

-

“... made the Senate angry with the consuls, whose tardiness had led to the betrayal of [the Aurunci]. They therefore ordered a dictator to be appointed. The nomination fell to C. Claudius Inregillensis, who named C. Claudius Hortator as his master of horse. A religious difficulty was then raised about the dictator and, when the augurs reported that there seemed to have been a flaw in his appointment, the dictator and his master of the horse resigned”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 15: 5-6).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 576) argued that the obscurity of C. Claudius Inregillensis and C. Claudius Hortator makes it unlikely that a dictatorship was invented for them. He was therefore inclined to accept its authenticity, although he considered that Livy’s explanation of the reasons for the appointment of a dictator was suspect, noting that:

-

“... this was a period in which there were many dictatorships, and it is easy to believe that only the bare notice of this one survived, without any indication of its purpose.”

War with the Sidicini and the Ausones of Cales (336-5 BC)

Events of 336 BC

According to Livy, the year of the consulship of L. Papirius Crassus and Caeso Duillius (336 BC):

-

“... was remarkable for a war (more novel than important) with the Ausones of Cales, who had joined forces with their neighbours, the Sidicini”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 16: 1-2).

The Ausones, who seem to have been ethnically related to the Aurunci, were based around Cales, a strategically-located stronghold that makes its entry into recorded history at this point. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 571) suggested that:

-

“The peoples east and west of the Roccamonfina may once have formed part of a united tribe, but it is probable enough that, by 337 BC, the power of the Sidicini had divided them.”

The novel feature of this war was apparently the fact that:

-

“The Romans defeated the army of the two peoples in a single and by no means memorable battle”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 16: 3).

This single defeat drove the two enemy armies back into their respective strongholds. However, it seems that the consuls were unable to take these strongholds and that the consular year ended in stalemate.

Events of 335 BC

According to Livy, as the consular elections approached:

-

“The Senate ... remained concerned over this war, because the Sidicini ... [had caused the Romans problems] so many times before. They therefore made every effort to elect M. Valerius Corvus, the greatest soldier of that age, to his fourth consulship, giving him M. Atilius Regulus as his colleague. [Furthermore], lest there should by chance be some miscarriage, they requested of the consuls that [Valerius] be given the command, without the drawing of lots ”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 16: 3-5).

Valerius therefore:

-

“... took over the victorious army from the previous consuls and marched on Cales, where the war had originated. He routed the Ausones (who had as yet not even recovered from the panic of the earlier encounter) and ... attacked [Cales] itself. ... [With the help of M. Fabius, a Roman prisoner at Cales who had escaped from his drunken guards], Valerius easily captured the Ausones and their city. ... Huge spoils were taken, a garrison was established in the town, and the legions were led back to Rome, where Valerius triumphed ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 16: 6-11).

Livy then recorded that:

-

“... lest Atilius should go without his share of glory, the Senate directed both consuls to march against the Sidicini, having named a dictator to preside at the elections. Their choice fell on L. Aemilius Mamercinus, who selected Q. Publilius Philo to be master of the horse. Under the presidency of the dictator, T. Veturius [Calvinus] and Sp. Postumius [Albinus]were chosen consuls”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 16: 11).

There are a number of problems with this account:

-

✴Livy stressed that the Senate had played a decisive role in securing Valerius’ election as consul As Nathan Rosenstein (referenced below, at p. 319) pointed out:

-

“Only in a single instance between 367 and 218 BC does evidence exist of a senatorial effort to influence the voters’ choice of consuls: in the elections for 335 BC, Livy reports that the [Senate] moved heaven and earth to ensure that the city's top general, M. Valerius Corvus, held the consulship for the fourth time, in order to lead a war against the Sidicini. Few, however, would be willing to take Livy's testimony for events [of this type] at such an early date at face value without strong corroborating evidence, of which none is forthcoming here.”

-

In other words, pace Livy, it is most unlikely that the Senate took unusual steps to ensure Corvus’ election.

-

✴Livy then had Valerius defeat the Ausones of Cales and return to the city in triumph. The fasti Triumphalis also record the award of a triumph to Valerius over the Caleni. However (as we shall see), the ‘Chronography of 354 AD’ recorded the consuls of 335 BC as ‘Caleno’ and ‘Corvo IV’, suggesting that Valerius’ colleague, M. Atilius Regulus (who is known only from these two sources) acquired the cognomen ‘Calenus’. Thus, as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 573) pointed out it is possible that a variant tradition credited him with this victory, and observed that:

-

“[Although] though the authority of the [Chronography] is not high, a victory is more likely to have been transferred to, rather than away from, Valerius Corvus. Alternatively, both consuls may have been involved in the fighting. This kind of problem is common in our sources for this period, ... but it need not affect the credibility of the evidence for the capture of Cales itself.”

-

In other words, although there is no reason to doubt that Cales was taken in 335 BC, we might reasonably doubt Livy’s insistence that M. Atilius Regulus (Calenus) played no part in this victory. This niggling uncertainty is arguably reinforced by Livy’s somewhat patronising assertion that:

-

“... so that Atilius might have his share of glory, the Senate [then] directed both consuls to march against the Sidicini ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 16: 11).

-

✴Livy recorded that the Senate took this unusual step so that Valerius could lead the war against the the Sidicini, but, as Nathan Rosenstein (referenced below, at p. 319, note 16) pointed out:

-

“... despite Livy’s mention of the Senate’s particular concern over this war, it seems to have been a comparatively minor affair.”

-

Indeed, as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 573) observed, Livy did not record:

-

“... any battle against the Sidicini [in this year], and the Romans probably contented themselves with plundering.”

It is therefore possible that, in this year:

-

✴Atilius acquired his agnomen ‘Calenus’ when he defeated and triumphed over the Ausones of Cales; and

-

✴Valerius confined his activities to the Sidicini without securing a definitive victory over them.

According to Livy (‘History of Rome’ 8: 16: 12), L. Aemilius Mamercinus was appointed as dictator to hold the elections for the consuls of the following year, which suggests that suggests that Valerius and Atilius remained in the territory of the Sidicini until they were relieved by the new consuls.

Dictator Year 334/3 BC

The year in which T. Veturius Calvinus and Sp. Postumius Albinus served as consuls is conventionally referred to as 334/3 BC. I set out the background to this odd dating convention in my page on Dictator Years (334/3; 325/4; 310/9; and 302/1 BC): in summary, it arises because:

-

✴a scholar who was working in the late Republic inserted into the annalistic record four fictitious years in which a dictator held office without consuls in order to resolve difficulties with the Roman calendar; and

-

✴although these fictitious years were included in (for example) the Augustan fasti Capitolini and were reflected in the contemporary fasti Triumphales, they were ignored by all of our surviving annalistic sources (including Livy).

Andrew Drummond (referenced below, 1978, at pp. 556-63), in his fundamental paper on the dictator years, suggested that the ‘guilty’ scholar was probably T. Pomponius Atticus, in the ‘Liber Annalis’, which was published in 47 BC.

The entry in the fasti Capitolini for 334/3 no longer survive. However, the ‘Chronography of 354 AD’, which was probably based on them, recorded the relevant consulships of this period as follows:

-

335 BC: Consuls: Caleno [=M. Atilius Regulus (Calenus)] and Corvo IV [= M. Valerius Corvus]

-

334 BC: Consuls: Caudino [=Sp. Postumius Albinus (Caudinus)] and Calvino [= T. Veturius Calvinus]

-

333 BC: In this year there was a dictator and a master of horse, without any consuls

-

329 BC: Privernas II [= L. Aemilius Mamercinus Privernas] and Deciao (= C. Plautius Decianus]

In these transcriptions, I have:

-

✴completed the names of magistrates from other sources;

-

✴rendered in bold the names of triumphing magistrates recorded in the fasti Triumphales; and

-

✴completed the entry for 333 BC from the equivalent line in the fasti Capitolini for 309 BC.

We might now compare this dating with that of Livy, who (as noted above) ignored the year in which the fasti recorded the rule of a dictator without consuls: if we designate the consular year of M. Atilius Regulus and M. Valerius Corvus as ‘Year 1’’ and indicate Livy’s triumphing magistrates in bold, we have:

-

Yr 1 (= 335 BC in the fasti): Consuls: M. Atilius Regulus and M. Valerius Corvus

-

Yr 2 (= 334 and 333 BC in the fasti): Consuls: Sp. Postumius Albinus and T. Veturius Calvinus

-

Dictator: P. Cornelius Rufinus (with M. Antonius as his master of horse)

-

Yr 6 (= 329 BC in the fasti): Consuls: L. Aemilius Mamercinus Privernas and C. Plautius Decianus

This illustrates how the conventional designation of Livy’s ‘Year 2’ as 334/3 BC removes the complications caused by the fictitious dictator year in the official fasti.

Unfortunately, the ‘Chronography of 354 AD’, which is our only source for a dictator year in 334/3 BC, did not name the corresponding dictator. However, we can identify the dictators who allegedly held office in the other three dictator years from the fasti Triumphales (which are complete for the whole of the period relevant to this discussion):

-

✴325/4 BC: L. Papirius Cursor, as dictator for the first time, defeated the Samnites and was awarded his first triumph;

-

✴310/9 BC: L. Papirius Cursor, as dictator for the second time, defeated the Samnites and was awarded his third triumph; and

-

✴302/1 BC: M. Valerius Corvus, as dictator for the second time, defeated the Etruscans and the Marsi and was awarded his fourth triumph.

Livy dealt with these triumphs by describing the heroic deeds of the dictator in question in his account of the preceding consular year. On this basis, Andrew Drummond (referenced below, 1978, at p. 565, note 93 and p. 572) made what he called ‘the usual assumption’ that the dictator of the first dictator year was the man whom Livy had recorded as dictator in 334/3 BC: namely P. Cornelius Rufinus. I return to this assumption below.

Foundation of a Latin Colony at Cales

According to Livy,

-

“Under the presidency of the dictator (see above), T. Veturius [Calvinus] and Sp. Postumius [Albinus] were chosen consuls [for 334/3 BC. Despite the fact that war with the Sidicini continued, they first] brought in a proposal for sending out a colony to Cales in order to anticipate the desires of the plebs by doing them a service. The Senate resolved that 2,500 men should be enrolled for [the new colony], and they appointed a commission of three:

-

✴Caeso Duillius, [the consul of 336 BC];

-

✴T. Quinctius [Poenus, the consul of 354 and 351 BC]; and

-

✴M. Fabius [either Ambustus (cos. 360, 356 and 354 BC); or Dorsuo (cos. 345 BC];

-

to conduct the settlers to the land and to apportion it amongst them”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 16: 12-4, see Amanda Coles, referenced below, at pp. 311-2 for the identities of these commissioners).

Velleius Patroculus (‘Roman History’, 1: 14: 3) also dated the foundation of this colony to 334/3 BC.

Cales was a Latin colony, as evidenced be the fact that it appeared in Livy’s list of the 30 Latin colonies that existed in 209 BC (at ‘History of Rome’, 27: 9: 7). Furthermore, it was the first such colony to be added to the list, alongside five continuing priscae Latinae coloniae (Ardea; Circeii; Norba; Setia; and Signia). Its foundation thus marked an important development in Rome’s expansionist policy. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 582) observed its site:

-

“... was a strategic one:

-

✴it guarded the western foothills of the Monti Trebulani, which, at this point, were controlled by the Samnites;

-

✴its territory separated the Sidicini ... from [the] Samnites; and

-

✴above all, it was only 13 km northwest of Capua, which it was thus able to watch.”

Resumed war with the Sidicini

According to Livy, having presented their plans to the Senate for the new colony at Cales, Veturius and Postumius:

-

“... took over the army from their predecessors and, entering the territory of the Sidicini, laid it waste as far as the walls of the [unnamed] city”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 17: 1).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at pp. 573-4) suggested that:

-

✴the Romans had probably contented themselves with plundering the territory of the Sidicini in 335 BC, possibly because Teanum Sidicinum was so well fortified that they did not dare to attack it; and

-

✴the unnamed city mentioned in the passage quoted above in the context of the campaign of 334/3 BC was probably Teanum Sidicinum.

He also suggested (at p. 574) that the bland account in this passage:

-

“... may well be no more than annalistic reconstruction for a campaign about which the authentic testimony was silent ...”

It seems to me that the most likely scenario is that Valerius and Atilius had begun the siege of Teanum Sidicinum in 335 BC, and that Veturius and Postumius took over this besieging army.

Appointment of P. Cornelius Rufinus as Dictator

Livy then flagged up a sudden state of emergency:

-

“At this juncture, since:

-

✴the Sidicini had raised an enormous army and seemed likely to make a desperate struggle on behalf of their last hope [of survival]; and

-

✴there was a rumour that Samnium was arming;

-

the Senate authorised the consuls to nominate a dictator. They appointed P. Cornelius Rufinus, and M. Antonius was made master of horse. [However], a scruple was subsequently raised about their appointment, and they resigned their office ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 17: 2-4).

There is no reason to doubt that:

-

✴Veturius and Postumius, at the behest of the Senate, appointed Rufinus as dictator; and

-

✴he appointed Antonius as his master of horse.

However, neither of them is known to have had any experience of military command: as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at pp. 587-8) observed:

-

✴Livy’s account of this vitiated dictatorship is the only reference to Rufinus in our surviving sources (although he might have been the grandfather of P. Cornelius Cn. f. P. n. Rufinus, the consul of 290 BC and thus a direct ancestor of Sulla); and

-

✴his master of horse, M. Antonius, is also otherwise unknown (although he could have been a direct ancestor of the homonymous consuls of 99 BC and 44 BC).

It is therefore most unlikely that Rufinus was appointed to deal with a military emergency (particularly since men like M. Valerius Corvus would have been available, had the need arisen). On the other hand, as we shall see, Livy recorded that there was an epidemic in Rome at this time, which means that Rufinus could have been appointed clavi figendi caussa (to fix the nail) as Cn. Quinctius Capitolinus was in 331 BC (see below).

What is clear is that, if Livy is correct in his assertion that Rufinus’ appointment was immediately vitiated, he most certainly did not appear in the fasti as the dictator who served without consuls in 333 BC (as discussed further below)

Interregnum

Livy recorded that a plague that followed Rufinus’ vitiated appointment as dictator was taken as a sign that:

-

“... all the auspices had been affected by [the irregularity in his appointment], and the state reverted to an interregnum”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 17: 4).

In other words, it seems that the irregularity in Rufinus’ appointment was so serious that it also removed the consuls’ power to preside over the election of their successors, causing the Senate to appoint one of its members as interrex in order to do so. Is so, then the first interrex would have been appointed for a period of 5 days, on the understanding that, if he proved unable to complete these elections within that time, he would choose a successor, in a process that would continue until the elections were completed. According to Livy, on this occasion:

-

“... M. Valerius Corvus, the fifth interrex from the beginning of the interregnum, finally achieved the election to the consulship of Aulus Cornelius [Cossus Arvina] (for the second time) and Cn. Domitius [Corvinus]”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 17: 5).

We should pause again at this point to consider the reliability of Livy’s claims that:

-

✴the putative flaw in Rufinus’ appointment impugned ‘all of the auspices’, including those of both consuls, so that an interex was needed to preside over the election of the consuls for the following year; and

-

✴four interreges failed before the fifth, M. Valerius Corvus, succeeded.

Confidence in these claims is undermined by facts that Sp. Postumius Albinus and T. Veturius Calvinus held the consulship together on two occasions (in 334/3 BC and again in 321 BC) and that, on each occasion:

-

✴the Senate called upon them to appoint a dictator;

-

✴his appointment was subsequently vitiated;

-

✴this led to an interregnum followed by the election of the consuls for the following year under the auspices of the interrex M. Valerius Corvus.

This surely suggests that there is some duplication at work here.

-

✴In 321 BC, Veturius and Postumius were in command of the armies that were disastrously defeated by the Samnites at the Caudine Forks and, after their subsequent return to Rome, they:

-

“... shut themselves up in their houses and refused to transact any public business, except that the Senate forced them to name a dictator to preside at the election [of their successors]. They designated Q. Fabius Ambustus [as dictator], with P. Aelius Paetus as the master of the horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 7: 12-13).

-

As in 334/3 BC, the dictator’s appointment was soon vitiated:

-

“A flaw in [the appointment of the dictator and the master of horse] occasioned [their] replacement by M. Aemilius Papus, as dictator and L. Valerius Flaccus, as master of the horse. However, they too failed to hold an election and, because the people were dissatisfied with all the magistrates of that year, the state reverted to an interregnum”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 7: 12-14).

-

On this occasion:

-

“The interreges were Q. Fabius Maximus , [followed by] M. Valerius Corvus. ... [who] announced the election to the consulship of Q. Publilius Philo ... and L. Papirius Cursor ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 7: 15-16).

-

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 113) argued that it is unsurprising that there was a political crisis in Rome after the defeat at the Caudine Forks in 321 BC, and that this probably explains the vitiation in quick succession of the dictatorships Fabius Ambustus and (probably) of M. Aemilius Papus. Furthermore, the loss of faith among the electorate in the magisterial class probably explains the need for a respected interrex such as M. Valerius Corvus to preside over the election of new consuls.

-

✴There is nothing in Livy’s account that suggests that there was a similar political crisis at Rome in 334/3 BC. It is, of course, perfectly possible that:

-

•neither consul was available to preside over the elections, perhaps because they both remained in the territory of the Sidicini; and

-

•M. Valerius Corvus was therefore appointed in some capacity in order to performed this task.

-

However, if so, then he is more likely to have presided over the consular elections as dictator (see below).

End of the War with the Sidicini (332 BC)

Livy recorded that, when the consuls of 332 BC, Cn. Domitius Calvinus and A. Cornelius Cossus Arvina, took office:

-

“There was now peace.

-

✴[However, a rumour of a Gallic War led to the appointment of M. Papirius Crassus as dictator, but this proved to be a false alarm.]

-

✴Samnium likewise had now for two years been suspected of hatching revolutionary schemes, for which reason the Roman army was not withdrawn from the Sidicine country. However, an invasion by Alexander of Epirus in drew the Samnites off into Lucania,”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 17: 6-9).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 574) observed:

-

“At this point, the Sidicini disappear from Livy’s narrative until [297 BC, see ‘History of Rome’, 10: 14: 4], and we should probably assume that some kind of treaty brought an end to the fighting.”

As we have seen:

-

✴in 335 BC, Valerius and Atilius had apparently begun the siege of Teanum Sidicinum; and

-

✴in 334/3 BC, Veturius and Postumius:

-

“... took over the army from their predecessors and, entering the territory of the Sidicini, laid it waste as far as the walls of the [unnamed] city”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 17: 1).

Livy did not report any further fighting, and he did not indicate that Domitius and Cornelius had entered the territory of the Sidicini as consuls. It therefore seems to me that

-

✴the ‘two years’ in which the Romans had maintained a presence in this territory had been 335 and 334/3 BC;

-

✴by 332 BC, the Sidicini appreciated that, although Teanum Sidicini itself would be difficult to take by force, they would have to choose at some point between the hegemony of the Samnites or that of the Romans;

-

✴the arrival Alexander of Epirus in southern Italy in 334/3 BC (see Stephen Oakley, referenced below, 1998, at p. 406 for the date) would have led them to choose the Romans; and

-

✴their putative treaty between the Romans must therefore dated to late 334/3 BC or early 332 BC.

Events of 334/3 BC: Conclusions

In my view, although Veturius and Postumius might well have spent much of their consulship in the territory of the Sidicini, their task was simply to maintain the siege of Teanum Sidicini: Livy only mentioned the danger of an intervention of the Samnites as a rumour in 343/2 BC, presumably in order to account for Rufinus’ dictatorship. It is true that the foundation of the colony at Cales at the start of the year would have annoyed the Samnites, but (as Livy recognised) they had more important priorities when Alexander of Epirus appeared on their southern borders. Thus, the most likely scenario is that there was no military crisis in this year: rather, the Romans and the Sidicini arrived at a stalemate that ended with some sort of agreement (possibly enshrined in a treaty) in late 334/3 BC or early 332 BC.

In relation to the other magistracies of this year:

-

✴Livy was probably correct in recording Rufinius’ dictatorship, and possibly in recording its immediate vitiation. However, since there was arguably no military crisis in this year but there was probably an outbreak of plague, this dictatorship (whether vitiated or not) was probably clavi figendi caussa (for fixing the nail).

-

✴Livy was also possibly correct in recording that M. Valerius Corvinus presided over the election of the consuls of 332 BC, but there is no obvious reason why he would have done so as interrex, rather than as dictator comitiorum habendorum caussa (for holding elections).

This leaves us wondering why Atticus chose 334/3 BC for his first dictator year.

As noted above, we can be fairly certain how he selected the other three: each of these dictators had actually celebrated a triumph in the preceding consular year. Furthermore, John Rich (referenced below, in his tables at pp. 247-251 in which he completed the fasti Triumphales) concluded that there were only four dictator triumphs between 356 BC (when C. Marcius Rutulus triumphed as dictator) and 81 BC (when Sulla triumphed as dictator):

-

✴324 BC*: L. Papirius Cursor;

-

✴3o9 BC*: L. Papirius Cursor (for the second time);

-

✴302 BC: C. Junius Bubulcus Brutus; and

-

✴301 BC*: M. Valerius Corvus.

Thus, it seems that Atticus chose three of these dictator triumphs (those marked here by an asterisk) for re-allocation to a fictitious dictator-year (leaving Junius to triumph as dictator in the consular year 302 BC while pushing Valerius’ triumph forward into a fictitious dictator year.

However, Andrew Drummond (referenced below, at p. 570) argued that Atticus’ invention of the consul-free dictator years was:

-

“... so anomalous that some deeper motivation seems required beyond mere misunderstanding or the need to fill a supposed chronological gap. Nor is it difficult to supply that motivation if ... [these so-called] dictator years were invented ... [as late as] 47 BC.”

His point is that Atticus work would have been published at the height of the controversy that attended Caesar’s second dictatorship. According to Plutarch, after Caesar’s defeat of Pompey at Pharsalus in 48 BC:

-

“... he crossed to Italy and went up to Rome, at the close of the year, [and was, for] a second time ... chosen dictator, although that office had never before been for a whole year”, (‘Life of Caesar’, 51: 1).

Caesar left Italy soon after this appointment in order to engage with the remnants of Pompey’s army, and Plutarch noted that:

-

“... he chose Mark Antony as his master of horse and sent him to Rome. This office is second in rank when the dictator is in the city; but when he is absent, it is the first ...”, (‘Life of Mark Antony’, 8:3).

Cassius Dio recorded that:

-

“... the augurs strongly opposed [the appointment of Mark Antony], declaring that no-one could be master of horse for more than six months. This gave rise to a great deal of ridicule because, after having decided that the dictator himself should be chosen for a year, contrary to all precedent, they were now splitting hairs about the master of the horse”, (‘Roman History’, 42: 21: 1-2).

This is probably indicative of the general reaction to the constitutional outrage of a dictator and his master of horse appointed for a year. The fasti Capitolini for this period record:

-

47 BC: Dictator: C. Julius Caesar [(II), magister equitum] M. Antonius [in order to manage public affairs] - It seems that Mark Antony’s name was removed from the fasti (perhaps after his defeat by the future Emperor Augustus in 30 BC) but subsequently reinstated.

-

Consuls in the same year: Q. Fufius Calenus and P. Vatinius

-

46 BC: Consuls: C. Julius Caesar (III) and M. Aemilius Lepidus.

A passage in a letter that Cicero sent to Atticus in December 48 BC (Letter to Atticus, 11: 7: 2, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, at p. 203) indicates that Mark Antony was acting as master of horse by that date. Thus, the likelihood is that this second dictatorship lasted for a calendar year and was followed by a short period with Q. Fufius Calenus and P. Vatinius as consuls. Andrew Drummond argued (at p. 571) that:

-

“It is difficult to believe that the sudden appearance ... of [dictator] years in works of just this period was independent of the controversy of 48 BC, or that Atticus would show sufficient independence to ignore fictions so convenient to Caesar and his lieutenant ...”

This probably explains why Atticus chose to characterise the four years that he added to the calendar as years in which a dictator and his master of horse ruled without consuls. However, Drummond made another observation as his parting shot (at pp. 571-2):

-

“ ... it was a further particularly happy notion that the [master of horse] of the first of these dictators (P. Cornelius Rufinus in [‘333 BC’ ]) should himself be a M. Antonius.”

In other words, Drummond suggested that Atticus chose 334/3 BC as his first dictator year because there was evidence to hand for:

-

✴an emergency in that year that had justified the appointment of a dictator; and

-

✴the appointment in that year of a dictator, P. Cornelius Rufinus, whose master of horse had been (or who could be represented as) an ancestor of Mark Antony.

Events in Rome (332-1 BC)

Rumours of a Gallic Invasion (332 BC)

As we have seen, Cn. Domitius Calvinus and A. Cornelius Cossus Arvina were elected consuls for 332 BC. Livy recorded that, at the start of their term of office:

-

“The rumour of a Gallic war (coming, as it did, when all was tranquil) worked like an actual rising, and caused the Senate to have recourse to a dictator. M. Papirius Crassus was the man, and he named P. Valerius Publicola as his master of the horse. While they were conducting their levy, more strenuously than they would have done for a war against a neighbouring state, scouts were sent out, and returned with the report that all was quiet amongst the Gauls”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 17: 6-7).

As Mark Wilson (referenced below, at pp. 422-3) observed, once Livy had recorded that:

-

“The Gauls [were reported to be quiet] and the Samnites [had been] drawn off to fight Alexander of Epirus, nothing further is said of Papirius’s dictatorship.”

Census of 332 BC

Red asterisks = centres incorporated as non-colonial civitates optimo iure by 332 BC:

Tusculum (in 381 BC); and Nomentum, Pedum, Lanuvium and probably Veltrae (in 338 BC)

Red dots = citizen colonies: Ostia (probably before 350 BC) and Antium (338 BC)

According to Livy, in 332 BC:

-

“... the census was taken and new citizens were assessed. On their account, the Maecian and Scaptian tribes were added. The censors who added them were Q. Publilius Philo and Sp. Postumius”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 17: 11).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 592) pointed out that:

-

“This was the first census since the settlement of 338 BC [that ended the Latin War]:

-

✴It put into effect the measures of that year and allowed the new [full citizens from cities in Latium] to vote in their tribes ...; and

-

✴it re-registered Romans who had gone to settle on [land in Latium that had been confiscated in 340 and 338 BC].

-

Some of the new registrations could be could be incorporated by extensions [of the territories] of existing tribes but, as this was not always [practical], two new tribes had to be created.”

Tusculum, Aricia, Nomentum and Pedum

Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, 1960, at p. 41) noted that there is, in fact, a dearth of epigraphic evidence for the tribes to which the newly-enfranchised peoples of Latium were assigned. However, she noted (at p. 43) that at least two of the six peoples under discussion here (both of which were about 25 km from Rome) can be securely assigned to existing tribes:

-

✴Tusculum was assigned to the Papiria; and

-

✴Aricia was assigned to the Horatia.

She further suggested (at pp. 43-4) that the people of Nomentum and Pedum (both of which were also about 25 km from Rome) might also been assigned to old tribes (the Cornelia and the Menenia respectively), although Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 543, note2) argued that the tribes of these two centres are, in fact, unknown.

Ostia, Antium and the Voturia Tribe

According to Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 42) Ostia, Rome’s oldest maritime colony, was securely assigned to the ancient Voturia tribe. She also suggested (at p. 42 and in her more detailed analysis at at p. 320) that the Voturia:

-

“.... was extended down the coast [from Ostia] to Antium [in 332 BC. However], the much more abundant testimony for the Quirina [at Antium] needs to be explained. I suggest that it was a secondary tribe... , given to veterans settled in a colony there by [the Emperor Nero (54 - 68 AD)] soon after his succession.”

The evidence for Nero’s colony rests with Suetonius, who recorded that Nero was born in Antium (‘Life of Nero’, 6:1), and added that:

-

“He established a colony at Antium, enrolling the veterans of the praetorian guard and joining with them the wealthiest of the chief centurions, whom he compelled to change their residence; and he also made a harbour there at great expense”, (‘Life of Nero’, 9:1).

In other words, it is possible that the Voturia was extended southwards in 332 BC for:

-

✴the registration of the newly-enfranchised Antiates;

-

✴the re-registration of the newly-enrolled colonists from Rome.

On this model, Nero (for whatever reason) would have arranged for the veterans that he settled there in ca. 54 AD to be registered in the Quirina.

Heikki Solin (referenced below, at p. 75), in his discussion of the epigraphic evidence for the tribe of Antium. He concluded that it indicated two possible candidates: the Quirina and/or the Voturia:

-

✴the evidence for the Quirina is extensive and secure, but this tribe was created only in 241 BC; while

-

✴the evidence for the Voturia rests on only two inscriptions, neither of which (as we shall see) can be securely related to a native of Antium.

It has to be said that the epigraphic evidence for the presence of the Voturia at Antium before ca. 54 AD consists of only a single inscription (CIL VI 0903), which records an aedile, L. Scrìbonius Celer, of the Voturia tribe and which can be securely dated to 36 AD. Furthermore, as Heikki Solin (referenced below, at p. 76) pointed out, Scribonius might have come from Ostia, where his family name was well-attested. Nevertheless, the southwards extension of the Voturia would have been an obvious way of accommodating the new colonists and the newly-enfranchised Antiates in 332 BC. Solin concluded (at p.7) that:

-

“The tribal history of Antium remains an open question, although hypothesis of ... Lily Ross Taylor is certainly possible, even plausible” (my translation).

New Citizens Assigned to the Maecia and Scaptia

We might reasonably assume that citizens at Lanuvium and Velitrae would have been assigned to one of the new tribes of 332 BC:

-

✴Livy (above) recorded that these new tribes were needed for the new citizens; and

-

✴since Lanuvium and Velitrae (both about 35 km from Rome) were the two newly-incorporated centres that were furthest from Rome, they are likely to have been the the least easily absorbed into existing voting districts.

Lanuvium and the Maecia

The evidence that Lanuvium was assigned to the Maecia is compelling:

According to Paul’s epitome of Festus’ epitome of the now-lost lexicon of the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus:

-

“Maecia tribus a quodam castro sic appellata”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 121 Lindsay

-

“The Maecia tribe was named for a castrum (military camp)” (my translation)

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 407) pointed out:

-

“... we know [from Livy, ‘History of Rome’, 6: 2: 8] that this [castrum] was not far from Lanuvium ... [and thus that] Lanuvium was almost certainly in the Maecia tribe ...”

(See also, Lily Ross Taylor, referenced below: at p. 54 and note 24; and at p. 273, where she listed a number of senatorial families from Lanuvium that were assigned to the Maecia.)

Velitrae and the Scaptia

Since the Maecia was probably formed for Lanuvium, it is tempting to assume (with Lily Ross Taylor, referenced below, at p. 55) that the Scaptia was created for the Roman citizens at Velitrae:

-

✴Taylor herself assumed that the people of Velitrae were incorporated without voting rights in 338 BC, and that the Scaptia was created for citizens from Rome who settled on land that had been confiscated from the exiled Veliternian senators.

-

✴However, as discussed above, it is possible that the tribe was created for both existing (but re-registered) and new Roman citizens at Veliitrae.

However, there is no hard evidence to support either of these hypotheses since we know neither:

-

✴the precise location of the Scaptia voting district; nor

-

✴the tribe to which the citizens at Velitrae were assigned.

As far as the location of the Scaptia voting district is concerned, we have the testimony of Paul’s epitome of Festus’ epitome of the now-lost lexicon of the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus:

-

“S<captia tribus a no> mine urbis Scaptiae a<ppellata, quam Latini > incolebant””, (‘De verborum significatu’, 465 Lindsay)

-

“The Scaptia tribe is named for the Latin city of that name” (my translation)

According to Pliny the Elder (who was writing in the 1st century AD), Scaptia was among the 53:

-

“... famous towns of Latium ... [that had] disappeared without leaving any traces of their existence”, (‘Natural History’, 3:9).

There are two main strands of scholarly thought as to its original location:

-

✴Julius Beloch (referenced below, at p. 26) placed it between Ardea and Aricia, because (according to Livy, ‘History of Rome’, 3: 71-72), when these two centres both claimed a particular piece of land in 466 BC, an old man called Scaptius testified that, as a young soldier, he had fought with the army that had won the land in question for Rome.

-

✴As noted above, Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at pp. 54-5) suggested that the Scaptia had more probably been created for the Romans who settled on confiscated land at Velitrae in 338 BC. She based this on evidence from Suetonius’ biography of Caius Octavius (better known as the Emperor Augustus), to the effect that:

-

•“... the family of the Octavii was of the first distinction in Velitrae” (‘Life of Augustus’, 1); and

-

•“[Augustus was enrolled in both] the Fabian and Scaptian tribes”, (‘Life of Augustus’, 40: 2).

-

She reasoned that, since the Fabia was the tribe of Augustus’ father by adoption (Julius Caesar), the Scaptia must have been the tribe of his natural father (also called Caius Octavius) and this branch of the gens Octavii, and thus of the people of Velitrae.

Unfortunately, it is not certain that Velitrae was assigned to the Scaptia in 338 BC. The surviving epigraphic evidence for the tribe of Velitrae is unhelpful in this respect: Heikki Solin (referenced below, at p. 77) cited four surviving inscriptions, each of which apparently related to a native of the town, and each of which placed the native in question in a different tribe: the Clustumina; the Pollia; the Quirina; or the Stellatina. He observed that this disparate evidence:

-

“... does not rule out the possibility that ... , when [the people of Velitrae finally received] full citizenship, its inhabitants were registered in [the Scaptia]. However, this cannot be demonstrated from the sources at our disposal: [in the absence of any other evidence], the fact that Augustus' father belonged to the Scaptia is not enough to prove that this was the tribe of the people of Velitrae, because his family was not necessarily of remote Veliternian origin” (my translation).

Given these uncertainties, there are at least two schools of thought, as represented by the opinions of Heikki Solin and Stephen Oakley:

-

✴Heikki Solin (referenced below, at p. 77), who believed that the people of Velitrae had been incorporated in 338 BC without voting rights, concluded that:

-

“I would look for the territory of the Scaptia tribe (according to Livy and in agreement with Beloch) between Ardea and Aricia” (my translation).

-

✴Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 592), who believed that the people of Velitrae had been incorporated with voting rights, was of the opinion that:

-

“On current evidence, the matter [of their tribal assignation at this point] must remain undecided.”

However, he observed (at p. 543) that, whether the Scaptia was between Ardea and Aricia or around Velitrae:

-

“... the creation, in 332 BC of ... the Maecia and the Scaptia [would have] linked the outlying Pomptina and Poblilia [voting districts] with the rest of Roman territory.”

Events of 331 BC

According to Livy, 331 BC was:

-

“A terrible year ... , whether owing to the unseasonable weather or to man's depravity. The consuls were M. Claudius Marcellus and C. Valerius: I find Flaccus and Potitus severally given in the annals, as the surname of Valerius, but it does not greatly signify where the truth lies in regard to this”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 18: 1-2).

The fasti Capitolini record the Valerian consul as C. Valerius Potitus.

More importantly, this was the year of the first known magistracy of Q.Fabius Maximus: as we shall see, he served in this year as he curule aedile.

Appointment of a Dictator Clavi Figendi Causa (331 BC)

Livy recorded reluctantly that the year witnessed a spate of deaths among the leading citizens of Rome and, while originally attributed to an epidemic of some sort:

-

“... were in reality destroyed by poison”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 18: 3).

The truth came to light when:

-

“... a certain serving woman came to Q. Fabius Maximus [Rullianus], the curule aedile, and declared that she would reveal the cause of the general calamity, if he would give her a pledge that she should not suffer for her testimony. Fabius at once referred the matter to the consuls, and the consuls to the Senate ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 18: 4-6).

This led to an investigation that revealed that some 170 Roman matrons were tried and found guilty of murder. Livy noted that:

-

“... there had never before been a trial for poisoning in Rome. [The behaviour of the matrons] was regarded as a prodigy, and suggested madness rather than felonious intent. Accordingly, when a tradition was revived from the annals, which recorded that:

-

✴in secessions of the plebs, a nail had been driven by the dictator; and

-

✴how the minds of men who had been driven mad by civil discord had been restored to sanity by that act of atonement;

-

[the Senate] resolved on the appointment of a dictator to hammer in the nail. The appointment went to Cn. Quinctilius, who named L. Valerius master of the horse. The nail was [duly] hammered in and they [then] resigned”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 18: 11-13).

The fasti Capitolini record this dictatorship but disagree with Livy as to the identities of the dictator and his master of horse: they named

-

✴Cn. Quinctius Capitolinus as dictator clavi figendi causa; with

-

✴C. Valerius Potitus, son of L., as his master of horse (after he resigned as consul).

Renewed Threat from Samnium (331 BC)

In 334 BC, the Greek city-state of Tarentum (who were threatened by the Lucanians and Apulians) had invited the mercenary Alexander of Epirus to Italy to come to their aid. However, he soon began to operate on his own behalf in both Lucania and Apulia. According to Livy, his operations :

-

“... [ had drawn] the Samnites off into Lucania, and these two peoples [i.e., the Samnites and the Lucanians] engaged in a pitched battle with [Alexander] as he was marching up from Paestum. The victory remained with Alexander, who then made a treaty of peace with the Romans; with what faith he intended to keep it, had the rest of his campaign been equally successful, is a question”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 17: 9-10).

However the Samnites were freed from this distraction when Alexander was murdered in 331 BC, and they were now able to address the growing threat from the Romans on their northwestern border.

Privernum and Fundi (330 -328 BC)

With the Sidicini, the Hernici, the Antiates and the northern Campani securely under Roman control, the days of Volscian independence were obviously numbered. Thus, Livy recorded that, in 330 BC:

-

“... ambassadors came to Rome from the Volscians of Fabrateria and the Lucani, requesting acceptance into the fides of Rome and promising that, if they were defended from the arms of the Samnites, they would faithfully and obediently accept the government of the Roman people. The Senate sent ambassadors to warn the Samnites to refrain from aggression against these peoples. This embassy proved effective, not because the Samnites were desirous of peace, but because they were not [yet] prepared for war”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 19: 1-3).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at pp. 606-7) explained, the most natural reading of ‘ex Volscis Fabraterni et Lucani’ is that both were Volscian centres, albeit that Volscian Luca is otherwise unknown.

Revolt of the Peoples of Privernum and Fundi (330 - 329 BC)

We should start by summarising Livy’s account of the relevant events of 341 -33 BC:

-

✴In 341 BC, after a brief revolt, Privernum surrendered to Rome. Although it retained its independence at this point, it suffered the confiscation of two thirds of its territory (‘History of Rome’, 8: 1: 3).

-

✴In 340 BC, this confiscated land was distributed in small allotments among the Roman plebs (‘History of Rome’, 8: 11: 15).

-

✴In 338 BC:

-

“... the peoples of Fundi and Formiae [were granted civitas sine suffragio], because they had always afforded [the Romans] a safe and peaceful passage through their territories [presumably even during the Latin War]”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 14: 10).

Then, in 330 BC, at a time when (as noted above) the Samnites were causing trouble in the area:

-

“... a war broke out [between the Romans and] the people of Privernum, who were supported by the people of [recently-incorporated people of] Fundi were their supporters. The [rebel] leader was Vitruvius Vaccus of Fundi, who was a man of distinction, not only at home, but also in Rome ... [The consul] L.s Papirius Crassus, having set out to oppose him whilst he was devastating the [Roman-controlled] districts of Setia, Norba, and Cora, posted himself near his camp. ... [Vitruvius’ army was easily defeated and] repaired to Privernum in trepidation, so that the soldiers might protect themselves within its walls ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 19: 4-9).

In 329 BC, the consul C. Plautius Decianus was charged with ending the revolt at Privernum. Livy had at least two sources for the subsequent events:

-

“Some say, that Privernum was taken by storm, and that Vitruvius was taken alive, while others maintain that the townsmen surrendered to Plautius ... and that Vitruvius was delivered up by his own troops”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 20: 6).

In any event, after Plautius’ success:

-

“The Senate ... sent word that [he] should demolish the walls of Privernum and, leaving a strong garrison there, return to Rome and enjoy the honour of a triumph. They also ordered that Vitruvius should be kept in prison in Rome until Plautius arrived ... [Furthermore], they decreed that all those who had continued to act as a senator of Privernum during the revolt should henceforth reside on the farther side of the Tiber, under the same restrictions as [the exiled senators] of Velitrae [see above]. ... Vitruvius and his accomplices were put to death after Plautius had triumphed”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 20: 4-10).

The fasti Triumphales record that both consuls (Plautius and his colleague L. Aemilius Mamercinus, who is given the surname ‘Privernas’) were awarded triumphs against the Privernates.

Settlement with Privernum

According to Livy, Plautius argued in the Senate against any further punishment of the people of Privernum, who:

-

“... are neighbours to the Samnites, whose peaceful relations with ourselves are at this time most precarious: [we should therefore ensure] that as little bad feeling as possible is created between them and us”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 20: 12).

This argument prevailed, and it was agreed that:

-

“... a bill to confer civitas to the people of Privernum should be brought before the people”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 21: 10).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 620) argued that:

-

“... this grant of citizenship [to the people of Privernum] must have been sine suffragio ..."

Settlement with Fundi (and Formiae ?)

There had, of course, been repercussions for the people of Fundi: in 330 BC, while L. Papirius Crassus was engaged at Privernum:

-

“The other consul, L. Plautius Venox ... led his army into the territory of Fundi. The senate there met him as he was crossing their borders, declaring that they had not come to intercede on behalf of Vitruvius [and] his faction, but on behalf of the [other, blameless] people of Fundi ... [where there was] ... gratitude for the [Roman] citizenship that the people had received. They begged Plautius to refrain from war .... Plautius ... [duly] despatched letters to Rome [reporting that] the people of Fundi had preserved their allegiance, and then marched on Privernum”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 19: 9-13).

Livy acknowledged that the annalist Q. Claudius Quadrigarius had recorded a different version of the fate of the people of Fundi:

-

“Claudius states that Plautius first punished those people of Fundi who had been at the head of the conspiracy. According to him, 350 of the conspirators were sent in chains to Rome, but that the Senate refused to accept their submission because they considered that the people of Fundi wished to escape with impunity by the punishment of needy and humble persons”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 19: 14).

However, Livy does not inform us of the penalty (if any) inflicted on Fundi in this version of events.

Colonies (329 -8 BC)

Underlined in red = Latin colonies: Cales (334/3 BC); and Fregellae (328 BC)

Underlined in green = maritime colony of Tarracina (39 BC)

Colonia Maritima at Anxur/ Tarracina (329 BC)

Livy ended his account of 329 BC by recording that:

-

“... 300 colonists were sent to Anxur, where they each received 200 iugera of land”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 21: 10-11).

Velleius Patroculus (‘Roman History’, 1: 14: 4) also recorded the foundation of a colony here in 329 BC, albeit that he referred to it by its Roman name, Tarracina. It was the first citizen colony that the Romans had created since that of Antium in 338 BC. Livy listed it among the seven coloniae maritimae that resisted an emergency military levy in 207 BC. As discussed below, it is likely that it was founded on land that had been confiscated from Privernum. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 621) suggested that:

-

“... its foundation in the year in which Privernum and Fundi were defeated can hardly have been coincidental, and its purpose will have been to exercise some control over the activities of those Volscian towns.”

As we shall see on the following page, the citizen colonists at Tarracina were probably registered in a new tribe, the Oufentina, which was created in 318 BC.

Fregellae (328 BC)

Livy noted (somewhat laconically) that the following year (328 BC):

-

“... was not marked by any significant military or domestic event, except that a colony was sent out to Fregellae, a territory that had belonged [originally] to the people of Signia [sic ?], and afterwards to the Volsci”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 22: 1-2).

Fregellae occupied a strategically-important site at the confluence of the Liris and the Sacco/Tolerus rivers. Although Livy claimed here that the new colony had been built on Volscian territory, this was disingenuous: when the Romans sent envoys to the Samnites in 326 BC to demand redress for their alleged transgressions before declaring war, they countered by saying (inter alia) that:

-

“... they could not disguise the chagrin of the Samnite nation that Fregellae, which they had captured from the Volsci and destroyed, should have been restored by the Roman people, and that a colony [had been] planted in the territory of the Samnites that the Roman settlers called by that name””, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 23: 6).

Fregellae fell to the Samnites at least once during the war that followed, as the Romans and Samnites fought for control of the Liris valley.

Read more:

Coles A. J., “Founding Colonies and Fostering Careers in the Middle Republic”, Classical Journal, 112:3 (2017) 280-317

Wilson M., "The Needed Man: Evolution, Abandonment, and Resurrection of the Roman Dictatorship" (2017) thesis of City University of New York

Solin H., “Problemi delle tribù nel Lazio meridionale”, in

Silvestrini M. (editor)), “Le Tribù Romane: Atti della XVIe Rencontre sur l’Epigraphie du Monde Romaine (Bari, 8-10 Ottobre 2009)”, (2010) Bari, at pp. 71-9

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume III: Books IX”, (2005) Oxford

Shackleton Bailey D. (translator), “Cicero: Letters to Atticus, Volume III”, (1999) Cambridge MA

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume II: Books VII and VIII”, (1998) Oxford

Cornell T. J. , “The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (ca. 1000-264 BC)”, (1995) London and New York

Rosenstein N., “Competition and Crisis in Mid-Republican Rome”, Phoenix, 47: 4 (1993), 313-38

Welch K., “The Praefectura Urbis of 45 B.C. and the Ambitions of L. Cornelius Balbus”, Antichthon, 24 (1990) 53-69

Drummond A., “The Dictator Years”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 27:4 (1978), 550-72

Falconer W, (translator), “Cicero: On Old Age; On Friendship; On Divination”, (1923) Cambridge MA

Return to Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)