Verrucosus’ Extraordinary Career

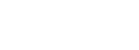

Copy of the Augustan elogium of Q. Fabius Maximus Verrucosus (, Museo della Civiltà Romana, Rome

The original (CIL XI 1828), from Arezzo, is now in the National Archaeological Museum, Florence

Verrucosus’ career was summarised in the inscription under his statue in the Augustan Forum, which probably belongs to the period 19 - 2 BC. Only a small fragment of the original has come down to us, but it can be completed from the copy of it that survives among the so-called elogia Arretina:

-

“[Quintus Fabius] Maximus, son of Quintus, twice dictator, consul five times, censor, twice interrex, curule aedile, twice quaestor, twice military tribune, pontifex, and augur.

-

✴In his first consulship, he subdued the Ligurians and he celebrated a triumph over them.

-

✴In his third and fourth consulships, he held in check warlike Hannibal from several victories by following him around.

-

✴The dictator came to the aid of Minucius, the master of the horse, whose imperium the people had made equal with the imperium of the dictator, and he came to the aid of the army after they had been conquered, and for that reason he was addressed by the name father by the Minucian army.

-

✴As consul a fifth time, he captured Tarentum, he celebrated a triumph.

-

He was considered the most cautious commander of his own generation and the most experienced in military affairs. He was appointed as the first man in the Senate for two periods of five year”, (CIL XI 1828, translated by Brad Johnson, referenced below, at p. 101).

Rachel Feig Vishnia (referenced below, at p. 19, note 2) observed that:

-

“It is unlikely that elogia in general and this one in particular would contain false information, as there were many who could refute it. ... [Verrucosus] was:

-

✴dictator for the 2nd time in 217 BC;

-

✴dictator, probably for holding the elections, sometime between 222 and 219 BC [see below];

-

✴consul in 233, 228, 215, 214 [and] 209 BC [and triumphed during his 1st and 5th consulships]; [and]

-

✴censor in 230 BC.

-

The elogium is the only source recording both his [two] interregna and the lower magistracies. He was pontifex from 216 BC and augur from 265 BC, [assuming he replaced his recently-deceased father, and] was chosen princeps senatus in 209 and 204 BC.”

Rachel Feig Vishnia observed (at p. 19, note 2) that the most surprising thing about Verrucosus’ career is that, despite his impeccable family credentials:

-

“... it seems highly probable... that, when [he] was first elected consul in 233 BC, he was about 60 years old, far older than the average age of consuls in that period.”

Having analysed all of the surviving sources that pointed tin this direction, she concluded (at p. 23) that:

-

“... Verrucosus was at least 90 years old when he died [in 203 BC], which means that he was born [at about the time] of his father’s first consulship (292 BC) and perhaps even earlier, and was [indeed] about 60 years old when he became consul for the first time in 233 BC.”

Livy honoured Verrucocus with an unusually long obituary:

-

“The death occurred [in 203 BC] of Quintus Fabius Maximus at a very advanced age ( if it be true, as some authorities assert, that he had been augur for 62 years). He was a man who [would have] deserved the great surname that he bore, even if he had been the first to bear it. He surpassed his father in his distinctions, and equalled his grandfather, Rullianus]:

-

✴[the grandfather] had won more victories and fought greater battles; but

-

✴[the] grandson had Hannibal for an opponent and that made up for everything.

-

He was held to be cautious rather than energetic, and though it [is debatable] whether he was naturally slow in action or whether he adopted these tactics as especially suitable to the character of the war, nothing is more certain that that, as Ennius says:

-

‘One man, by his slowness, restored the State’.

-

He had been both augur and pontifex; his son Q. Fabius Maximus succeeded him as augur and Ser. Sulpicius Galba as pontifex”, (‘History of Rome’, 30: 26: 7-11).

Cicero (‘On Duties’, 1: 84) recorded a fuller version of the praise that Verrucosus had been given by the epic poet Ennius (ca. 17o BC):

-

“One man, cunctando (by delaying), restored the State to us. He did not put popular opinion above safety: so now the man’s glory shines ever brighter with passing time”, (‘Annales’, Book 12, fragment 1, translated by Sander Goldberg and Gesine Manuwald, referenced below, at p. 293).

First Two Consulships of Verrucosus

First Consulship (233 BC)

Gareth Sampson (referenced below, at pp. 52 -6) described what little is known about the first of Rome’s wars with the Ligurians, an Italic tribe that had been pushed out of the Po valley by the Gauls and subsequently taken refuge in the mountains of northwest Italy (overlooking modern Genoa). This first ‘war’ (238 - 233 BC) was probably caused by the Ligurians’ role as mercenaries in the pay of the Sardinians, since the fasti Triumphales record triumphs awarded to:

-

✴P. Cornelius Lentulus,, over the Ligurians in 236 BC;

-

✴T. Manlius Torquatus, over the Sardinians in 235 BC;

-

✴Sp. Carvilius Maximus, over the Sardinians in 234 BC;

-

✴M'. Pomponius M'.f. M'.n. Matho, over the Sardinians in 233 BC; and

-

✴Q. Fabius Maximus Verrucosus over the Ligurians in 233 BC.

Plutarch recorded that, in the battle that led to his first triumph in 233 BC, Verrucosus:

-

“... defeated [the Ligurians] in battle, inflicting heavy losses on them in the process, and they retired into the Alps, where they ceased plundering and harrying the adjacent parts of Italy”, (‘Life of Fabius Maximus’, 2: 1).

It therfore seems that Verrucosus had dealt with a Ligurian incursion into the Po valley, and that his action had brought an end to hostilities there.

The only other surviving record for Verrucosus’ actions as consul at this time comes in passage by Cicero (ca. 45 BC):

-

“Vides Virtutis templum vides Honoris (You can see the temple of Virtus; you can see [the temple] of Honos), restored by M. Marcellus, which Q. Maximus had dedicated many years earlier, during the war with Liguria”, (‘On the Nature of the Gods’, 2: 61, translated by H. Harris Rackham, referenced below, at p. 181).

This is the only surviving literary source for the existence of a templ of Honos outside Porta Capena, which Verrucosus presumably dedicated as consul in 233 BC [Link to my page on temples of Honos and Virtus].

Second Consulship (228 BC)

Almost nothing is known about the events of this year, except that Cn. Fulvius Centumalus was awarded a naval triumph over the Illyrians as proconsul.

Two (?) Dictatorships of Verrucosus

The second part of the entry in the fasti Capitolini for 217 BC can be translated as:

-

Dictator: Q. Fabius Q.f. Q.n. Maximus Verrucosus; master of horse: M. Minucius C.f. C.n. Rufus - because of an interregnum (interregni caussa).

No record of Verrucosus as dictator II appears in these fasti, which survive in their entirety for the period between 219 and 203 BC (the year of Verrucosus’ death). As we have seen, the Augustan elogium (above) had Verrucosus as dictator on two occasions and (as we shall see), Livy recorded that almost all of his sources recorded that the dictatorship of 217 BC had been Verrucosus’ second. This apparent discrepancy can only be reconciled if we assume that:

-

✴Verrucosus’ first dictatorship dated to the period 221-219 BC, for which the relevant entries in the fasti no longer survive (see, for example, the comment to this effect by Rachel Feig Vishnia); and

-

✴he should have been, but was not, recorded as dictator II in the surviving entry for 217 BC.

This would also explain why we have no account by Livy of Verrucosus’ first dictatorship: it would have been recorded in his now-lost Book 20, which covered the period ca. 240-220 BC.

Verrucosus’ Putative First Dictatorship

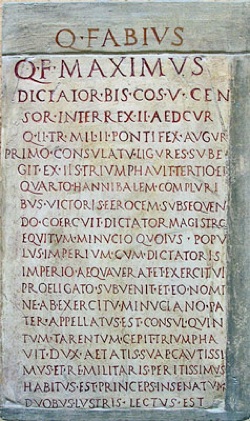

CIL VI 0284: Hercolei sacrom M(arcus) Minuci(us) C(ai) f(ilius), dictator vovit

From via Tiburtina, in the Campo Verano, now in Musei Capitolini

Image from the website ‘History of Ancient Rome’

We can throw further light on the likely date of Verrucosus’ earlier dictatorship by considering what we know about the career of Minucius, his master of horse in 217 BC. The evidence of two inscriptions is of direct relevance here:

-

✴As we have seen, the Augustan elogium recorded that, in 217 BC, Verrucosus:

-

“... came to the aid of Minucius, the master of the horse, whose imperium the people had made equal with the imperium of the dictator, and he came to the aid of the army after they had been conquered, and for that reason he was addressed by the name father by the Minucian army.”

-

I discuss the circumstances in which these events took place below: for the moment, we might simply note that Minucius arguably held the rank of dictator for part of 217 BC.

-

✴The inscription illustrated above (which is on a tufa block that served as the base of a statue) indicates that this was a statue to Hercules that Minucius had dedicated as dictator (almost certainly for the first time).

The obvious conclusion would be that Minucius had dedicated this statue of Hercules shortly after the enhancement of his imperium to equality with that of Verrucosus.

However, Plutarch recorded another occasion on which Minucius served as dictator: in a digression in which he discussedthe importance that the Romans attached to the religious aspects of the appointment of their magistrates, he recorded that:

-

“... because the squeak of a shrew-mouse (the Romans call it ‘sorex’) was heard just as Minucius, the dictator, appointed C. Flaminius as his master of horse, the people deposed these officials and put others in their places”, (‘Life of Marcellus’, 5: 4).

If this record reflected a genuine dictatorship of Minucius, then:

-

✴since it is not recorded in either the surviving books by Livy or the surviving entries in the fasti Capitolini, it must date to the period 221-219 BC inclusive; and

-

✴since nothing in the surviving sources indicates the need for a dictator for military purposes at this time, Minucius must have been appointed comitiorum habendorum caussa (in order to hold [consular] elections).

We can rule out 221 BC because, as Robert Broughton (referenced below, at p. 235, note 3) pointed out, he and his consular colleague engaged in an expedition against the Istrians: he was therefore either:

-

✴available in Rome at the end of that year in order to hold the elections as consul: or

-

✴still in Istria, and thus unavailable to hold elections in Rome.

On the other hand, since Flaminius began his term as censor in 220 BC, he is unlikely to have been nominated as master of horse in either 220 or (pace Mark Wilson, referenced below, 2017, at p.550, entry 73) in 219 BC. Thus, Plutarch was almost certainly incorrect when he claimed that Minucius had chosen Flaminius as master of horse, which leaves us with two possibilities:

-

✴Minucius was appointed as dictator comitiorum habendorum caussa in 219 BC, and chose a now-unknown master of horse (and that he dedicated the statue of Hercules recorded in inscription illustrated above during this, his first dictatorship); or

-

✴the testimony of Plutarch (our only source for Minucius’ putative earlier dictatorship) should be completely rejected, in which case:

-

•there is no basis for the assumption that Minucius held a dictatorship at any time before 217 BC; and

-

•we must assume that he made the dedication to Hercules after his imperium was enhanced in 217 BC.

As it happens, there is a good reason for the complete rejection of Plutarch’s testimony: Valerius Maximus recorded that:

-

“... the singing of a sorex (shrew) furnished cause for the setting aside of the dictatorship of Q. Fabius Maximus [Verrucosus] and [his master of] horse, C. Flaminius”, (‘Memorable Deeds and Sayings’, 1: 5), translated by Mark Wilson, 2017, at p. 436).

There is no a priori reason why Verrucosus could not have been appointed as dictator comitiorum habendorum caussa in 221 BC, with Flaminius as his master of horse. Thus, Robert Broughton (referenced below, at p. 234):

-

✴asserted that Plutarch had been mistaken when he named Minucius rather than Verrucosus as the dictator who appointed Flaminius as his master of horse; and

-

✴attributed only one dictatorship to Minucius: that of 217 BC (see p. 243).

It was also the view of Michele Bellomo (referenced below, t p. 158 and note 34). On this basis, Minucius would probably have made this dedication to Hercules shortly after the enhancement of his imperium to equality with that of Verrucosus.

More importantly for our purposes, we might reasonably assume that Verrucosus was appointed as dictator for the first time in 221 BC in order to hold the elections for the consuls of the following year, and that he chose Flaminius as his master of horse on this occasion: as Mark Wilson (referenced below, 2017, at p, 436,note 36) observed:

-

“The controversial and ill-omened C. Flaminius, the consul who died at Lake Trasimene in 217 BC, would have been an attractive candidate for such a story [as the vitiation of both appointments because of the singing of a sorex].

Verrucosus’ Career to 217 BC: Conclusions

On the basis of the arguments made so far, it seems that Verrucosus was already about 75 years old when he became dictator in 217 BC, and that his career up to that point had proceeded as follows:

-

✴265 BC: probably appointed augur at this point (on the death of his father)

-

✴233 BC: consul I (when he was already about 60 years old)

-

✴230 BC: censor

-

✴228 BC: consul II

-

✴221 BC: dictator I in order to hold elections in the consuls’ absence - vitiated

-

✴217 BC: dictator II, shared imperium with Minucius for part of this year.

Verrucosus’ Appointment as Dictator (217 BC)

According to Polybius, when the news of the disaster at Trasimene arrived in Rome (probably in early July):

-

“... the [leading magistrates] were unable to conceal or soften the facts, owing to the magnitude of the calamity, and were obliged to summon a meeting of the people and announce it. The praetor [therefore] announced from the Rostra that:

-

‘We have been defeated in a great battle.’

-

This produced such consternation that, to those who were present on both occasions, the disaster seemed much greater now than it had seemed during the actual battle. ... [However] the Senate ... remained self-possessed, concentrating on the future, considering what should be done ... and how best to do it”, (‘Histories’, 3: 85: 7-10).

According to Livy, the arrival at Rome of the news from Trasimene:

-

“... brought the citizens into the Forum in a frightened and tumultuous throng ... The crowd, like some vast public assembly, turned to the Comitium and the Senate House and called for the magistrates [until], at last, Marcus Pomponius, the praetor, announced that:

-

‘A great battle has been fought, and we were beaten.’

-

Although they learned nothing more definite from him, they soon picked up a rumour ... that [Flaminius] and a great part of his soldiers had been [killed. .... While panic in the city mounted], the praetors kept the Senate in session in the Curia for some days, ... debating which commander ... could oppose the victorious Carthaginians”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 7: 14).

Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 660) suggested that M. Aemilius Regillus, the urban praetor, chaired the meeting in the Senate, assisted by M. Pomponius, praetor inter peregrinos. It is likely that, at this stage, the Senate was trying to decide whether:

-

✴a suffect consul should be appointed to take command of what remained of Flaminius’ army and to reinforce it with new recruits; or

-

✴a dictator should be given overall command against Hannibal .

However, according to Livy, when the news of Centenius’ defeat reached Rome, hot on the heels of the news from Trasimene:

-

“... the civitas (citizens) had recourse to a remedy that had been neither employed nor needed for a long time: the creation of a dictator”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 8: 5-6).

According to Polybius, it was at this point that the Romans:

-

“... appointed as dictator Quintus Fabius ... [and], at the same time, they appointed Marcus Minucius as master of horse”, (‘Histories’, 3: 87: 6-9).

The surviving accounts of the process by which Verrucosus and Minucius were appointed are somewhat at variance. As Livy described it:

-

“... because:

-

✴the [surviving consul, Servilius], who alone possessed the power to nominate [a dictator], was [still] absent; and

-

✴Italy was beset [by Carthaginian] arms, so that it was no easy matter to get a courier or a letter through to him;

-

the people did something that they had never been done before: they appointed Q. Fabius Maximus dictator and M. Minucius Rufus as master of horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 8: 5-6).

The relevant entry in the fasti Capitolini can be translated as:

-

Dictator: Q. Fabius Q.f. Q.n. Maximus Verrucosus; master of horse: M. Minucius C.f. C.n. Rufus - because of an interregnum (interregni caussa).

As far as we know, this is the only dictatorship recorded in the fasti Capitolini as interregni caussa, and, as Michele Bellomo (referenced below, at p. 151) observed, whatever this implied in precise procedural terms, it certainly indicated that:

-

“... the procedure of the interregnum was used for the nomination of the dictator”, (my translation

He argued that the testimonies of Livy and the fasti were incompatible, although Mark Wilson (referenced below, 2017, at p. 26) suggested a procedure that might have been consistent with both testimonies:

-

“With no consul available, [Verrucosus] was appointed [as dictator] by a meeting of the comitia tributa (assembly of the people), the lex [that permitted this appointment] perhaps being rogated [i.e., put to the assembly] by a presiding interrex, [who would have been appointed by the Senate for the purpose].”

As Mark Wilson (referenced below, 2021, at p. 290) pointed out, we know of another occasion on which an interrex was involved in the appointment of a dictator: when Sulla had himself appointed as dictator in 82 BC, he arranged for the appointment of an interrex who would lay the necessary legislation before the Senate (see, for example, Frederik Vervaet, referenced below, at p. 39). Since none of the surviving sources for the appointment of 217 BC records the appointment of an interrex for the purpose of lay the necessary legislation before the comitia tributa, we cannot rule out the possibility that the intervention of an interrex in 217 BC was ‘discovered’ only in 82 BC.

Our surviving sources also differ in relation to the way in which Minucius was appointed. As we have seen, both Polybius and Livy claimed that he, like Verrucosus, had been appointed by the comitia tributa. However, Plutarch gave a slightly different account of these events, in which Pomponius’ speech (also described by both Polybius and Livy):

-

“... threw the City into commotion ... [It was agreed] that the situation demanded a sole and absolute authority, which [the Romans] call a dictatorship, and ... that [Verrucosus], and he alone, was [qualified for the task] ... This course was adopted, and [Verrucosus] was appointed dictator: he himself appointed Marcus Minucius to be his master of horse”, (‘Life of Fabius Maximus’, 3:4 - 4:1).

This would have been entirely conventional: indeed, as Mark Wilson (referenced below, 2017, at p. 159) observed, the election of a master of horse by the comitia tributa would have been:

-

“... as great a deviation [from the established norms] as the election of a dictator, if not a greater.”

Nevertheless, Plutarch’s next remark suggests that, even if [Verrucosus] had formally appointed his own master of horse, he had felt the need to underline his right of overall command in the field, since he:

-

“... at once asked permission of the Senate to use a horse himself when in the field, [although] this ... was forbidden by an ancient law”, (‘Life of Fabius Maximus’, 4: 1).

Mark Wilson (referenced below, 2017, at p. 159) argued that:

-

“If the choice [of Minucius had been] imposed on [Verrucosus] by the masses [as recorded by Polybius and Livy, then this] might at least explain why [Verrucosus ended up with a master of horse who was] so out of sympathy with his own strategies and tactics [see below].”

None of the sources considered so far (including Livy, at ‘History of Rome’, 22: 8: 6) expressed any doubts that Verrucosus had been elected dictator by the comitia tributa.

To sum up: it is likely that Verrucosus and Minucius were appointed as dictator and master of horse respectively at this time under an unprecedented procedure in which:

-

✴the Senate elected an interrex;

-

✴this interrex convened the comitia tributa and put before it a law in which:

-

•both men were named; and

-

•their designated task was defined as the defence of Rome during the current emergency; and

-

✴the comitia tributa duly approved the law that had been put before them.

As we have seen, we can trace the record of Verrucosus’ unprecedented appointment as dictator by ‘the people’ back to Coelius (late 2nd century BC). However, the role of an interrex in his appointment is deduced from a single source, the Augustan fasti Capitolini, which describe Verrucosus (but no other dictator, as far as we know) as dictator interregni caussa.

Livy’s Change of Heart

As we have seen, Livy initially described Verrucosus’ dictatorship of 217 BC as his second (‘History of Rome’, 22: 9: 7). He also described the law that Metilius (the plebeian tribune) had drafted and Varro (an ex-praetor) had put before a public assembly part way through Verrucosus’ term as:

-

“... a moderate measure de aequando magistri equitum et dictatoris iure (that the master of horse should have the same legal status as the dictator)”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 25: 10).

Significantly, at this point in his narrative, Livy still regarded Verrucosus as dictator and Minucius as his master of horse, even after this legislation had passed. Three later sources also maintained this view:

-

✴the fasti Capitolini named Verrucosus as dictator in this year, with Minucius as his master of horse;

-

✴the elogium of Verrucosus (above) referred to Minucius as:

-

“... [Verrucosus’] master of the horse, whose imperium the people had made equal with the imperium of the dictator ... ”, (CIL XI 1828, translated by Brad Johnson, referenced below, at p. 101); and

-

✴Plutarch recorded that:

-

“[The people] voted that Minucius should:

-

•have an equal share in the command [against Hannibal]; and

-

•conduct the war with the same powers as [Verrucosus];

-

a thing which had not happened before in Rome”, (‘Life of Fabius Maximus’, 9: 3).

However, our earliest surviving source, Polybius (ca. 150 BC) flatly contradicted this later evidence:

-

“[The Romans] took an entirely unprecedented step, investing [Minucius], like [Verrucosus], with absolute power, in the belief that he would very soon put an end to the war. So, two dictators were actually appointed for the same field of action, a thing which had never before happened at Rome”, (‘Histories’, 3: 103: 3-4).

For Polybius, after the legislation mentioned above was passed, Verrucosus and Minucius were both dictators.

It is therefore somewhat surprising that Livy subsequently changed his mind and became convinced that, in 217 BC, Verrucosus had been appointed pro dictatore (as an ‘acting dictator). He began by reiterating that:

-

“Nearly all the annalists state that [Verrucosus] was [serving as] dictator in his campaign against Hannibal; Coelius even writes that he was the first man to be created dictator by the people”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 31: 8-9)

Livy’s ‘Coelius’ was almost certainly L. Coelius Antipater, the author of a history of the Hannibalic War in late 2nd century BC (see, for example, John Briscoe, in T. J. Cornell (editor), referenced below: vol. I, at pp. 256-7; and vol. III, at pp. 248). Briscoe observed that, while Livy still accepted that almost all writers agreed that Verrucosus was dictator in 217 BC it seems that:

-

“... at least one annalist said that [he was rather] pro dictatore.”

He argued (at p. 249) that Coelius (who clearly held the majority view) had apparently:

-

“... emphasised, perhaps at the end of his narrative of [Verrucosus’] campaign, the fact that [he] was the first directly-elected dictator: there is no implication:

-

✴that other writers consulted by Livy thought [that there had been earlier directly-elected dictators]; or

-

✴... that Coelius was the only writer to say that [Verrucosus] was popularly elected.”

Livy now decided to reject the majority view because:

-

“... Coelius and the rest forget that the right to appoint a dictator lay with the one surviving consul, Cn. Servilius, who was at that time far off in his province of Gaul]. It was because the Romans, appalled by their great disaster, could not countenance a long a delay that they resorted to the popular election of an acting dictator (pro dictatore)”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 31: 9-11).

It seems that, on reflection, Livy had concluded that it was easier to believe that Verrucosus had been appointed as an unprecedented pro dictatore than that he had been appointed as a ‘full’ dictator by an unprecedented vote of the people (even though all of the sources available to him had apparently accepted this ‘fact’).

John Briscoe (in T. J. Cornell (editor), referenced below: vol. III, at p. 248) observed that this was one of six occasions in the surviving books on which Livy added a ‘self correction’. The most famous of these variant passages came at the end of his account of the events of 437 BC, when he discussed an amendment to his account of the dedication of the spolia opima in the temple of Jupiter Feretrius: his earlier sources had all claimed that A. Cornelius Cossus had dedicated them as military tribune in 437 BC, but this was:

-

“... confuted by the actual inscription on the spoils, which ... Augustus Caesar ... read ... with his own eyes, ... [and in which Cossus] described himself ... as consul, [the post that he held in 428 BC]”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 6-11).

Interestingly, Livy based his argument for the self-correction under discussion here partly on epigraphic evidence: he suggested that the judgement of ‘Coelius and the rest’ had been clouded by:

-

“... [Verrucossus’] successes, his great renown and augentes titulum imaginis posteros (augmentations by his descendants to the inscription on his image), [which] made it easy to believe that one who had been made [only] acting dictator had been a [full] dictator”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 31: 11).

While it is tempting to identify Livy’s ‘augmented’ inscription on Verrucossus’ image as the elogium (late 1st century BC) in the Forum of Augustus (which certainly described Verrucosus as having served as dictator on two occasions), it seems to me that he must have had in mind here an inscription that had been ‘augmented’ by the gens Fabia and had arguably been misleading ‘Coelius and the rest’ since at least the late 2nd century BC. [I wonder, for example, whether the Fornix Fabianus (121 BC) sported an image of Verrucosus that gave him two dictatorships for the first time, but this is mere speculation.]

Given the flimsy nature of the case made by Livy for this self-correction, it is perhaps unsurprising that most scholars have rejected it. For example, John Briscoe argued (at vol. III, p. 249) that Livy was almost certainly incorrect here, and that, in 217 BC:

-

“The Romans ... [had] demonstrated their customary flexibility in a crisis. All [of our other surviving] sources ... concur that [Verrucosus] was dictator and either explicitly state or are consistent with the view that [he] was elected by the comitia.”

Robert Broughton (referenced below, at p. 245, note 2) similarly dismissed Livy’s suggestion that Verrucosus was elected pro dictatore in 217 BC as ‘unacceptable’. In any case, as Gregory Golden (referenced below, at p. 29) wisely remarked:

-

“... it really is unimportant whether [Verrucosus] was, in legal terms, dictator or only pro dictore. The strange designation ‘interregni caussa’ in the [fasti Capitolini ] is also immaterial. [We might reasonably add that the precise procedure by which Minucius became [Verrucosus’] master of horse is of little fundamental significance]. ... [The key fact is that, from the time of Verrucosus’ appointment, he] carried out the duties normal for a dictator named to face an external threat.”

In other words, Verrucosus acted as a ‘normal’ dictator rei gerundae caussa throughout his dictatorship and, as we shall see, he resigned when he had completed the task for which he had been appointed.

Events of Verrucosus’ Dictatorship

Verrucosus in Rome (July)

Livy recorded that Verrucosus:

-

“... convened the Senate on the day he entered upon his office. Taking up first the question of religion, he convinced the Fathers that the consul Flaminius had erred more through his neglect of the ceremonies and the auspices than through his recklessness and ignorance. ... He prevailed on them to do what is rarely done except when dreadful prodigies have been announced, and order the decemvirs to consult the Sibylline books. When the decemvirs had [done so], they reported to the Fathers that:

-

✴the offering that had been made to Mars on account of this war had not been duly performed and must be performed afresh and on a grander scale;

-

✴great games must be vowed to Jupiter;

-

✴temples must be vowed to Venus Erycina and to Mens;

-

✴a supplication and lectisternium must be celebrated in honour of the gods; and

-

✴a vow should be made to hold Sacred Spring, provided that the war went well and the State remained as it had been before the outbreak of hostilities.

-

The Senate, seeing that [Verrucosus] would be occupied with the conduct of the war, commanded Marcus Aemilius, the praetor, as the college of pontifices had recommended, to see that all these measures were promptly put into effect”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 9: 7-11).

These measures were duly put in hand and, before Verrucosus left Rome:

-

“The [two] temples were ... vowed:

-

✴that to Venus Erycina by [Verrucosus], the dictator, because the Books of Fate had given out that he whose authority in the state was paramount should make the vow; and

-

✴that to Mens by the praetor, T. Otacilius Crassus”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 10: 10).

Livy then recorded that, having attended to his religious duties, Verrucosus:

-

“... called on the Senate to decide the number and nature of the legions [that were needed to deal with the emergency]. It was decreed that he should take over Servilius’ army ... and enrol ... as many horsemen and foot-soldiers as he thought fit. ... [Verrucosus] announced that he would add two legions to the army, .... [which would be] enlisted by his master of the horse and ... assembled at Tibur on a given day. He also ordered that the inhabitants of unfortified towns and hamlets should move to places of safety; and that all those living in districts through which Hannibal was likely to march should abandon their farms after burning their buildings and destroying their crops, so that there might be no supplies for him of any kind”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 11: 1-4).

Verrucosus then went out to meet Servilius in order to assume command of his army: he left Rome:

-

“... by the Via Flaminia ... and when he approached the Tiber near Ocriculum (Otricoli), he first ... saw [Servilius] riding towards him at the head of his cavalry ... [He summoned Servilius] to appear before him without lictors. [Servilius] obeyed ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 11: 5-6).

This did not mean that Servilius was deprived of his imperium. Thus, when:

-

“... a dispatch arrived from the City, announcing that [the Roman] ships that had been taking supplies from Ostia to the army in Spain had been captured off the port of Cosa. ... [Verrucosus] ordered Servilius to leave at once for Ostia and to pursue the enemy's fleet and protect the coasts of Italy, manning [any ships that he could find] at Rome or Ostia”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 11: 6-8).

Verrucosus and Minucius in Campania (ca. July - October)

Verrucosus caught up with Hannibal at Arpi in Apulia, which he had reached by marching along the coastal plain. As Livy noted:

-

“He refused to stake all on a general engagement [with the Carthaginians]. However, by means of little skirmishes undertaken from a safe position and with a place of refuge close at hand, he at length accustomed his [demoralised] soldiers .. to be less unsure of their own courage and good fortune. Unfortunately, [Minucius was as frustrated as] Hannibal was ... by these prudent measures: [indeed], he was only prevented from plunging the Roman cause into ruin by [the fact that he enjoyed only] subordinate authority”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 12: 10-11).

Hannibal then increased the pressure on Verrucosus by marching across Samnium and into Campania, where he established his camp on the Volturnus. From this base, he pillaged the Roman ager Falernus, which was an important source of corn. Verrucosus refused to prevent these depredations, content to establish a base on Monte Massico from which he could potentially defend the routes to Rome along either Via Appia or Via Latina. Livy claimed that Minucius stridently and publicly opposed Verrucosus’ cautious strategy, and attributed to him a speech in which he asked the assembled soldiers:

-

“Have we come here as spectators, to enjoy the sight of our allies being butchered and their property burned? Even if we feel no shame in front of anyone else, do we not feel it before these fellow citizens of ours, men whom our fathers sent to Sinuessa as colonists to make this area secure from the Samnite foe? Now it is not s Samnite who is burning this land, but a Carthaginian foreigner, who has made his way here from the very ends of the earth thanks to our cunctatione et socordia (delays and inertia). Is this how far we fall short of our forefathers?”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 14: 3-5).

In this passage, Livy’s Minucius levels the charge of cunctatio against all those who had been responsible for handling of the war, although his target was clear: he was drawing on a now-lost passage by Ennius, which was preserved by Cicero (as mentioned above):

-

“How much better was the behaviour of [Verrucosus], of whom Ennius says:

-

‘One man, and he alone, restored our state by cunctando (delaying). Not in the least did fame, for him, take precedence over safety. Therefore, his glory now shines bright and grows ever brighter’”, (‘On Duties’,1: 24, translated by Walter Miller, referenced below, at p. 87).

Of course, in the mouth of Minucius, cunctatio (delay) was meant to earn Verrucosus a badge of shame, and Livy suggested that this rhetoric brought the army close to mutiny:

-

“The soldiers showed unmistakably that, if they had had the right to elect their own leader, they would have preferred Minucius to [Verrucosus]”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 14: 15).

If Hannibal had expected to find local allies in Campania at this time, he was temporarily disappointed. Furthermore, Verrucosus almost managed to block his escape route as winter approached. Interestingly, Livy gave equal credit to Minucius in this endeavour:

-

“It happened that Minucius had joined [Verrucosus] on that day: he had been sent to secure the pass ... [at Lautulae], above Tarracina, in order to prevent the Carthaginians from taking the Appian Way from Sinuessa into Roman territory. Combining their forces, [Verrucosus and Minucius] camped on the road where Hannibal was going to march. The enemy [camp] was two miles away. Next day the Carthaginians were on the march, filling the road which lay between the two camps. The Romans had formed up just under their rampart and clearly occupied the most advantageous position. ... The Carthaginians attacked at one point after another, dashing up and then retreating, but the Roman line stood firm. The battle was long drawn out but [Verrrucosus] had the better of the fighting: he lost 200 men while Hannibal lost 800. Hannibal now seemed to be hemmed in, since the road to Casilinum was blocked. The Romans had Capua and Samnium at their backs and all their wealthy allies to furnish them with provisions; but the Carthaginians faced the prospect of passing the winter and amid tangled forests between the cliffs of Formiae and the sands and marshes of Liternum”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 15: 11 - 16:4).

However, Hannibal managed to escape through the pass beside Mount Callicula and was able to return to Apulia, where he seized the town of Gerunium. Livy then recorded that Verrucosus:

-

“... established his camp in the country about Larinum [some 20 miles south of Geronium] and, being summoned thence to Rome on religious business, [ordered Minucius] to put more trust in prudence than in fortune ... [and thus to continues with his strategy of surveillance, containment and non-engagement]. When [Verrucosus] had thus fore-warned Minucius (albeit in vain), he set out for Rome”, (History of Rome’, 22: 18: 8-10).

With both armies now in their winter camps, the campaigning season was almost over, and Verrucosus probably returned to Rome in order to oversee the appointment of a suffect consul to replace the dead Flaminius (see below).

Verrucosus’ Return to Rome and Mincius’ ‘Co-Dictatorship’

It seems that Minucius’ allies had been active in Rome in the aftermath of Hannibal’s escape from Campania, to the extent that, when Verrucosus arrived in the City, he found them in the ascendant. Matters came to a head when news arrived that Minucius had engaged with Hannibal’s army outside Gerunium:

-

“6,000 of the enemy had been slain and fully 5,000 Romans. Nevertheless, though the losses had been so nearly equal, [the] foolish tale that was carried to Rome [was] of an extraordinary victory, with a letter from [Minucius himself] that was more foolish still”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 24: 14).

The response to this letter was electric:

-

“Then M. Metilius, a tribune of the plebs, cried out that this was past all bearing: not only had [Verrucosus] prevented a successful engagement being fought while he was present, but now he even objected that the victory was won, and persisted in drawing out the war and wasting time, in order that he might stay longer in ... sole possession of authority:

-

✴of the consuls:

-

•[Flaminius], had fallen in battle; and

-

•[Servilius], had been sent away from Italy on the pretext of pursuing the Punic fleet;

-

✴the two praetors were employed in places that had no need of a praetor at this time

-

•[T. Otacilius Crassus] in Sicily; and

-

•[A. Cornelis Mamulla] in Sardinia; and

-

✴[Minucius] had been kept almost a prisoner so that he might not ... carry out any military operation ...

-

Thus, it had actually come to pass that, not only Samnium, ... but also Campania and the districts of both Cales and Falerii had been utterly laid waste, while [Verrucosus] had remained aloof at Casilinum and used the legions of the Roman People to protect his own estate. The army ... and [Minucius] had been virtually ... confined within the rampart [at Casilinum] ... At last, when [Verrucosus] had left, they had come out from behind their fortifications ... routed their enemies and put them to flight”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 25: 3-9).

Having expressed what was probably the prevailing opinion among the Romans at that moment, Metilius came to the point:

-

“[Metilius claimed that], for all these reasons, he would have proposed the abrogation of [Verrucosus’] command if [he had thought that] the Roman plebs [would have agreed]; as it was, he would propose only a moderate measure de aequando magistri equitum et dictatoris iure (that the master of horse should have the same legal status as the dictator)”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 25: 10).

Verrucosus’ speech against this proposal seems to have cut no ice. He therefore:

-

“... presided over the election of M. Atilius Regulus [as suffect consul] and then he left by night for the army, so that he avoided taking a personal part in the [debate on Metilius’] resolution. When, at break of day, the people assembled for the consilium plebis, ... one man alone was found to urge the passage of the bill. This was C. Terentius Varro, a praetor of the year before ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 25: 17-9).

Livy remarked that:

-

“Everyone, whether in Rome or with the army, whether friend or foe, looked on the passing of this bill as an insult to [Verrucosus] ... While still on the way [back to Larinum], he received a dispatch from the Senate de aequato imperio (about the equal division of imperium). Since he was fairly confident that, though the authority of the commanders had been equalised, their abilities had not, he returned to the army with [his] spirit [unbroken] ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 26: 5-7).

According to Livy, it was Verrucosus who decided how Metilius’ law would actually be put into effect:

-

“Although he had been forced to share his imperium with [Minucius], it had not been taken from him ... He would not agree to [Minucius’ suggestion that each of them would command the shared army on alternate days]. Rather, he would divide the army and, [by continuing] with his own strategy [as commander of his own army], he would save what he could, since he was not permitted to save everything. He thus achieved the division of the legions between them, as was the normal practice for consuls. ...[Minucius] chose that [the camps of the two armies] should be separated”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 27: 8-10).

Perhaps inevitably, Minucius marched his army towards an almost certain defeat, until Verrucosus and his men marched to their rescue. According to Livy, after this close shave, the contrite Minucius:

-

“... marched in column to [Verrucosus’] camp, to the astonishment of [Verrucosus] himself and everyone else there. When they had planted their ensigns before the tribunal, [Minucius] advanced ... and addressed [Verrucosus] by the name of ‘Father’, and his entire army saluted [Verrucosus’] soldiers as their patrons. ... Minucius acknowledged that:

-

‘[To you, dictator], I owe both my own salvation and that of my men. And so, I am the first to reject and repeal that decree of the people, [which is] onerous to me rather than an honour,. I put myself, once more, under your imperium and auspices, and restore to you these standards and legions ... Please forgive us, order me to hold the position of master of horse, and allow these men to retain their various ranks’”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 30: 1-5).

While the scene above is probably taken from Livy’s imagination, it is entirely possible that Verrucosus was once more in overall command of all the Roman forces by the time that he and Hannibal returned to their respective winter quarters.

Servilius’ Naval Command (ca. July - October)

As we saw above, when Verrucosus had taken over command of Servilius’ army, he had sent Servilius to consolidate the Roman’s naval resources at Ostia and to protect the coasts of Italy. Thereafter, according to Livy, while Verrucosus had been occupied with his given task of containing Hannibal’s army, Servilius had left Ostia and:

-

“... sailed round Sardinia and Corsica with a fleet of 120 ships. After taking hostages from both [in order to deter them from helping the Carthaginians, he] sailed for ... the coast of Africa and disembarked his troops. [Some of his men], who went off to pillage the countryside, ... quickly fell into an ambush ... and were driven back to their ships in a bloody and disgraceful rout. Fully 1,000 men were lost, including the quaestor, Ti. Sempronius Blaesus. Moorings were cast off and the fleet ... [hurriedly departed] for Sicily. At Lilybaeum, it was handed over to the praetor, T. Otacilius, to be ... [returned] to Rome. Servilius himself proceeded overland through Sicily to the straits, where he crossed into Italy, in obedience to a dispatch from [Verrucosus]”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 31: 1-7).

Verrucosus Resignation and the Election of New Consuls

According to Livy, towards the end of the year:

-

“...[Verrucosus] had sent for both Servilius and [the suffect consul], M. Atilius [see above] ... to take over his armies [i.e., his own army and that of Minucius], since his semestri imperio (six-month command) was drawing to a close”, (‘History of Rome’, 22: 31: 7).

Since the disaster at Trasimene had occurred in late June (see above), Verrucosus’ semestri imperio (six-month command) would have ended in late December. This is often taken to mean that Verrucosus had been appointed as dictator in June for a fixed period of six months. However, as Mark Wilson (referenced below, 2021, at p. 254) pointed out, such an inflexible term for his imperium would have been:

-

“... unthinkable for [a dictator who had been] put at the head of Rome’s capacity for defence in [what was already] a year-long war that ... was going badly, ... and had recently resulted in unprecedented disasters.”

Wilson acknowledged that Appian had specifically recorded that:

-

“The six months that limited the terms of dictators among the Romans now expired, and the consuls Servilius and Atilius resumed their offices and came to the camp [at Larinum], while [Verrucosus] returned to Rome”, (‘Roman History’, 7: 16);

However, he rejected Appian’s interpretation of the situation, and argued (at p. 255) that what Livy had meant is that:

-

“... [Verrucosus]:

-

✴assessing the campaigning season to be over ... ; and

-

✴deciding that the task [of monitoring Hannibal in his winter camp] did not require a dictator, and was better performed by consuls;

-

saw saw his job as done. [He therefore] provided for his armies and stood down.”

On this basis, the course of events would have been as follows:

-

✴At the end of the campaigning season (December 217 BC), Verrucosus decided that he had accomplished the task for which he had been appointed and duly handed over command to the consuls Servilius and Atilius (‘History of Rome’, 22: 31: 7). This was the end of Livy’s narrative account of Verrucosus’ dictatorship: he presumably assumed that, at this point, Verrucosus and Minucius returned to Rome.

-

✴For the remaining part of the consular year (i.e., until the Ides of March, 216 BC), the consuls Servilius and Atilius carried on the war on the lines laid down by Verrucosus (‘History of Rome’, 22: 32: 1).

-

✴Neither Servilius nor Atilius felt able to return to Rome to preside over the election of their successors in March 216 BC, so they appointed a dictator, L. Veturius Philo, to act on their behalf. However, he had to resign on a technicality (‘History of Rome’, 22: 33: 11-2).

-

✴Servilius and Atilius were prorogued as proconsuls, although it is not clear on whose authority. An interregum was established (‘History of Rome’, 22: 34: 1) for the purpose of holding the consular elections.

-

✴After a tumultuous process presided over by the second interrex, L. Aemilius Paullus and C. Terentius Varro were elected. (‘History of Rome’, 22: 35: 4).

However, as Mark Wilson (referenced below, 2021, at p. 256) pointed out, Polybius flatly contradicted this version of events. In his account, when Verrucosus had saved his fellow-dictator, Minucius, from defeat:

-

“The Romans ... had received a practical lesson: [Verrucosus and Minucius] again fortified a single camp, joined their forces in it and in future, [Minucius ?] paid due attention to [Verrucosus] and his orders. The Carthaginians ... [duly] made their preparations [to winter at Geronium] undisturbed”, (‘Histories’, 3: 105: 11).

However. it is clear that Polybius still regarded Verrucosus and Minucius as co-dictators in March 216 BC, when:

-

“The time for the consular elections was ... approaching, and the Romans elected L, Aemilius Paulus and C. Terentius Varro. On their appointment, the dictators laid down their office. The consuls of the previous year, Cn. Servilius and M. Regulus (who had been appointed after the death of Flaminius) were invested with proconsular authority by Aemilius and, taking command in the field, directed the operations of their forces as they thought fit”, (‘Histories’, 3: 106: 1-2).

On this scenario, Servilius and Regulus either stayed with the army at Larinium over the winter or travelled there in March in order to take over command from the joint dictators, Verrucosus and Munucius, as proconsuls, at which point Verrucosus and Minucius presumably returned to Rome.

The scenarios presented by Polybius and by Livy are fundamentally irreconcilable, not least because Polybius believed that Verrucosus and Minucius held imperium of some sort from June 217 to March 216 BC. If one accepts the view expressed by Appian (and perhaps adumbrated by Livy) that dictators could not serve for more that six moths, then Polybius must have been mistaken. However, as Mark Wilson (referenced below, 2021, at p. 250) pointed out, our surviving historical narratives never record that, during a crisis that lasted for more than six months, a dictator either had his imperium extended or was replaced. Furthermore, in every case for which we have a clear narrative history, dictators were appointed for specific tasks, and in most cases, they retired voluntarily when they judged that task to have been completed. In other words, if Wilson’s analysis is accepted, then the only difference between the accounts of Livy and Polybius is that:

-

✴according to Livy, Verrucosus judged that his task had been completed by December, six months after his appointment, when the opposing armies had retired to their respective winter quarters; while

-

✴according to Polybius, Verrucosus judged that his task was completed when new consuls were elected in March 216 BC.

On balance, it seems to me that, once Hannibal had retired to his winter quarters at Gerunium, there would have been very little for Servilius and Attilius to do. Livy was therefore probably correct when he recorded that Verrucosus summoned both of them to Larinium at this point in order to hand over the armies there:

-

✴there is no reason to doubt that the praetor, T. Otacilius assumed Servilius’ naval command at this point since we find him in command of an augmented fleet of 75 ships on Sicily as propraetor in 216 BC (Livy, ‘Roman History’, 22: 37: 13); and

-

✴Attilius’ continued presence in Rome would have been unnecessary once the danger that Hannibal would march on the City had disappeared.

Read more:

Wilson M., “Dictator: The Evolution of the Roman Dictatorship”, (2021) Ann Arbor, Michigan

Goldberg S. M. and Manuwald G. (translators), “Ennius: Fragmentary Republican Latin, Vol. I:”, (2018), Cambridge, MA

Bellomo M., “Il Contributo delle Fonti Epigrafiche allo Studio della Seconda Guerra Punica: Alcuni Casi Eccezionali”, in:

M. Bellomo and S. Segenni (editors), “Epigrafia e Politica : il Contributo della Documentazione Epigrafica allo Studio delle Dinamiche Politiche nel Mondo Romano”, (2017) Milan, at pp. 147-70

Wilson M., "The Needed Man: Evolution, Abandonment and Resurrection of the Roman Dictatorship", (2017) thesis of City University of New York

Sampson G., “Rome Spreads Her Wings: Territorial Expansion Between the Punic Wars”, (2016) Barnsley

Cornell T. J. (editor), “The Fragments of the Roman Historians”, (2013) Oxford

Golden G., “Crisis Management During the Roman Republic: the Role of Political Institutions in Emergencies”, (2013) Cambridge

Feig Vishnia R., “The Delayed Career of the ‘Delayer’: The Early Years of Q. Fabius Maximus Verrucosus, the Cunctator”, Scripta Classica Israelica, 26 (2007) 20-37

Vervaet F. J., “The Lex Valeria and Sulla’s Empowerment as Dictator (82-79 BC)”, Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz, 15 (2004) 37-84

Johnson B., “The Elogia of the Augustan Forum”, (2001) thesis of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario

Brennan T. C., “The Praetorship in the Roman Republic”, (2000) Oxford

Broughton T. R. S., “Magistrates of the Roman Republic: Volume I”, (1951) New York

Rackham H. H. (translator), “Cicero: 'On the Nature of the Gods'; 'Academics'”, (1933), Cambridge MA.

Miller W. (translator), “Cicero: On Duties”, (1913), Cambridge, MA