Events of 311 BC

Livy recorded that the year started with military reforms. one result of which was that:

-

“... two military commands began to be conferred by the people; for it was enacted, first, that 16 military tribunes should henceforth be chosen by popular vote for the four legions: previously these places had been for the most part in the gift of dictators and consuls ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 30: 3).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 391) pointed out, we learn here:

-

“... that, at some point in or before 311 BC, the consular army was doubled from one legion to two.”

Livy also noted that, at this time, the Romans:

-

“ ... were preoccupied with two mighty wars”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 30: 10).

Timothy Cornell (referenced below, at p. 354) observed, although, from this point, the Romans:

-

“... were no longer in any serious danger of defeat ... [in Samnium, they conducted] campaigns [here] every year down to 304 BC, with varying success.”

However, this involved only one of the of the consular armies: as Cornell pointed out (at p. 355):

-

“... from around 312 BC onwards, the [war in Samnium] had ceased to be the Romans’ principal concern: ... [they now] concentrated their efforts ... on Etruria and Umbria ...”

Junius in Samnium

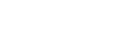

Cluviae = (probably) modern Piano Laroma, near Casoli

Bovianum = modern Boiano

Red dot = Interamna Lirena (Latin colony)

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

According to Livy, in 311 BC:

-

“The consuls [Caius Junius Bubulcus Brutus (for the third time) and Quintus Aemilius Barbula] divided the commands between them: to Junius the lot assigned the Samnites, to Aemilius the new war with Etruria”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 31: 1).

He recorded that:

-

“In Samnium, the Roman garrison at Cluviae, which had defended itself successfully against assault, was starved into submission. The Samnites ... [executed] the prisoners. Incensed by this ... Junius took the place by storm on the day he arrived before it, and killed all the adult males. From there, he led his victorious army to Bovianum ... [which was also taken]”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 31: 2-5).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 403) observed that there is no compelling reason to reject an attack on the relatively obscure settlement at Cluviae (assuming that it was near modern Casoli): since the Romans had already had successes against the Frentani in 319 BC , its location would not have posed a problem. However, he doubted that they could have marched on Bovianum, the capital of the territory of the Pentri, at this time.

Livy then had the Romans ambushed in saltum avium (in a remote glade), but they escaped and:

-

“... the Samnites [were caught] in a trap of their own devising: very few of them were able to escape, and some 20,000 of them men were killed”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 31: 16).

However Zonoras, after Cassius Dio, recorded that, in this ambush, the Romans:

-

“... met with disaster ... the Samnites surrounded them and slaughtered them ... ”, (‘Roman History’, 8: 1).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 404) observed that, since Junius vowed a temple to Salus during this engagement:

-

“... probably guarantees that [he] was not defeated too heavily, or at least that he finished the campaign with honour in tact.”

Livy did not refer to this vow here, but he later recorded that:

-

✴as censor in 306 BC, Junius:

-

“... let the contract for the temple of Salus [on the Quirinal], which he had vowed, while consul, during the Samnite war”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 43: 25); and

-

✴as dictator in 302/1 BC, he:

-

“... dedicated the temple of Salus, which he had vowed as consul, and the construction of which he had contracted for when censor”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 1: 9).

The Calendar of Philocalus records that the temple was dedicated on the nones (5th) of August.

The fasti Triumphales recorded that Junius was awarded a triumph over the Samnites in 311 BC, but Livy made no mention of it. Oakley (as above) suggested that, since the fasti Triumphales allege that this triumph was held on the same date as the [later] dedication of the temple (nones of August - see above):

-

“... it is perhaps best to reject it.”

However, it seems to me that the Senate might have done Junius the additional honour of dedicating ‘his’ temple on the anniversary of his triumph.

Events of 310/9 BC

Digression: Complication of a Dictator Year

This was the third of the four dictator years, so-called because:

-

✴in the fasti Capitolini:

-

•throughout 310 BC, Q. Fabius Maximus Rullianus (for the second time) and C. Marcius Rutilus served as consuls for the entire consular year of 310 BC; and

-

•throughout 309 BC, L. Papirius Cursor as a dictator for the second time and his master of horse, C. Junius Bubulcus Brutus, managed ‘public affairs’ without any consuls; and

-

✴in the fasti Triumphales, both Papirius and Fabius triumphed in 309 BC:

-

•Papirius, as dictator for the second time, over the Samnites; and

-

•Fabius, as proconsul, over the Etruscans.

In fact (discussed in my page on Dictator Years (334/3; 325/4; 310/9; and 302/1 BC)), four consul-free years (333, 324, 309 and 301 BC) were introduced in the late Republic in order to address difficulties with the Roman calendar. As far as we can tell, these fictitious years were ignored in all the later historical (as opposed to calendar-based) sources. Thus, Livy’ describes a single year in which the consuls were:

-

✴Q. Fabius Maximus Rullianus (for the second time), who campaigned in Etruria; and

-

✴C. Marcius Rutilus, who was wounded, presumed dead, in Samnium and replaced there by a dictator, L. Papirius Cursor, who appointed C. Junius Bubulcus Brutus as his master of horse.

Both Papirius and Fabius triumphed at the end of this consular year:

-

✴Papirius, over the Samnites; and

-

✴Fabius, over the Etruscans

For convenience, scholars designate this consular year as 310/9 BC.

C. Marcius Rutulus in Samnium

Livy recorded that:

-

“Quintus Fabius[Maximus Rullianus], consul [for the second time in 310/9 BC], took over the campaign at Sutrium [in Etruria] and was given Caius Marcius Rutulus as his colleague”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 33: 1).

Livy then launched his account of Fanius, campaign in Etruria. Five chapters later, we learn that:

-

“While these things were going on in Etruria, the other consul, Gaius Marcius Rutulus captured Allifae [in the valley of the Volturnus. near the border with Campania] from the Samnites by assault. Many other forts and villages were also either wiped out in the course of hostilities or fell to the Romans”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38: 1).

Diodorus Siculus also recorded that:

-

“Marcius, setting out against the Samnites, took the city of Allifae by storm and freed from danger those of the allies who were being besieged [there]”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 35: 2).

As we shall see below, Allifae, had changed hand on at leat two earlier occasions, was to change hands again in 307 BC..

Livy then switched to events in Etruria and, by the time that he returned to those in Samnium, Fabius had marched north from Sutrium through the Ciminian Forest and into upper Etruria. Livy described how the Romans feared that he might be marching into an ambush, similar to that of 321 BC at the Caudine Forks, and asserted that these fears among the Romans were matched by:

-

“... the rejoicings that took place among the Samnites ... However, their joy soon began to be mixed with [resentment] that Fortune should have transferred the glory of the Roman war from the Samnites to the Etruscans. So, they hastened to bring all their strength to bear upon crushing Caius Marcius ... Marcius met them [at an unspecified location], and the battle was fiercely contested on both sides, but without a decision being reached. Yet, although it was doubtful which side had suffered most, the report gained ground that the Romans had been worsted ... and, most conspicuous of their misfortunes, Marcius himself was wounded. These reverses ... were further exaggerated in the telling, and the Senate ... determined on the appointment of a dictator”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38: 4-10).

Obviously, this account of the Samnites’ inner thoughts must have been speculation on the part of Livy or his sources. However, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at pp. 460) pointed out that Marcius probably did suffer a reverse at this time, since:

-

“... the annalistic tradition is unlikely to have invented a Roman defeat ...”

However, Marcius was certainly not killed in this engagement: he served as a legate at the Battle of Sentinum (295 BC) and went on to be censor in 294 and again in 265 BC: he was given the name Censorinus during this unique second censorship.

Appointment of L. Papirius Cursor as Dictator

According to Livy, once the Senate had decided to transfer Marcius’ in Samnium to a dictator:

-

“Nobody could doubt that Papirius Cursor, who was regarded as the foremost soldier of his time, would be designated”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38: 10).

Formally, the appointment had to be made by one of the consuls and, since Marcius was missing in action, it had to be made by Fabius. Since he:

-

“... had a private grudge against Papirius, ... the Senate decided to send a deputation of former consuls to him ... [in order to] induce him to forget those quarrels in the national interest. The ambassadors [duly] went to Fabius and delivered the resolution of the Senate, with a discourse that suited their instructions”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38: 10-13).

Fabius, who had recently defeated the Etruscans in upper Etruria and agreed truces with Arretium, Cortona and Perusia, was presumably still at his camp in this region. His initial response to the ambassadors’ request were unsettling:

-

“Fabius, his eyes fixed on the ground, retired without a word ... Then, in the silence of the night, as custom dictates, he appointed Papirius dictator. When the envoys thanked him ... , he continued obstinately silent, ... so that it was clearly seen what agony his great heart was suppressing. Papirius named Caius Junius Bubulcus [the consul of 311 BC -see above], as his master of the horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38: 13-15).

Cassius Dio, gave a shorter account of these events:

-

“The men of the city put forward Papirius as dictator and, fearing that Fabius might be unwilling to name him on account of [their mutual hostility], they sent to him and begged him to place the national interest before his private grudge. Initially, he gave the envoys no response, but when night had come (according to ancient custom it was absolutely necessary that the dictator be appointed at night), he named Papirius, and by this act gained the greatest renown. (‘Roman History’, 8: 36: 26).

It seems likely that these accounts had a common source, albeit that Livy accepted or invented some elaborations relating to Fabius’ strange behaviour. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 461) observed that:

-

“In this period, the appointment of a dictator was a regular Roman response to military difficulty, and there is therefore no compelling reason to doubt [Papirius’ dictatorship], even if Livy’s account of panic at Rome after the defeat of Marcius derives only from his own imagination or that of his sources. Even though Diodorus Siculus ignored Papirius’ campaign against the Samnites, it would probably be an excess of scepticism to reject it out of hand.”

Papirius’ Engagement with the Samnites at Longula

Livy recorded that, immediately upon his appointment as dictator, Papirius:

-

“ ... took command of the legions that had been raised [at Rome] during the scare connected with [Fabius’ earlier campaign in Etruria], and led them to Longula [an unknown location, presumably in Samnium. There, having also taken] over Marcius’ troops, he marched out and offered battle, which the enemy on their part seemed willing to accept”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 39: 1-2).

Livy’s account of the subsequent engagement (presumably with the Samnites, although Livy did not name them) ended abruptly (at least in the surviving manuscripts):

-

“... while the two armies stood armed and ready for the conflict, ... night overtook them. [They retired to their respective camps], which were within a short distance of each other, and remained [there] for some days: they did not doubt their own strength, but neither did they underestimate that of the enemy”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 39: 3-4).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 499) pointed out that:

-

“It is quite likely that [this] was not originally the end of Livy’s description of this part of Papirius’ campaign, but was [instead] leading up to an account of a battle that was about to take place.”

He hardened this conclusion at p. 500:

-

“The arguments in favour of a lacuna after [“they remained quiet for some days, not through any distrust of their own strength or any feeling of contempt for the enemy”] ... are ... overwhelming.”

Papirius’ Victory the Samnites (perhaps at Longula)

Livy’s account resumed after this lacuna with a victory achieved by an un-named commanded over an Etruscan army that had been raised under a lex sacrata. He then observed that:

-

“The war in Samnium, immediately [after this war in Etruria], involved as much danger and reached an equally glorious conclusion”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 40: 1).

This sounds like a new war in Samnium, rather than a continuation of the engagement at Longula described above. However, if so, it is surprising that Livy did not describe its location and the circumstances that lead up to it. Indeed, it was to be some time before he referred directly to the fact that Papirius was in command of the victorious army.

Livy’s Account of the Glorious Battle

Instead, surprisingly, first Livy launched into an account of the Samnite armour:

-

“The enemy, besides their other warlike preparations, had made their battle line to glitter with new and splendid arms”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 40: 2).

This army that was now so splendidly attired was made up of two divisions:

-

✴the men of one, who wore multi-coloured tunics, had gilded shields and sheaths and golden baldrics, and the saddle cloths of their horses were embroidered with gold thread; and

-

✴the men of the other, who wore tunics of dazzling white linen, had silver shields, sheaths and baldrics.

The first of the corp fought in the left wing and the second on the right.

In the next section, again surprisingly, Livy put the initial exhortation to the Roman troops in indirect speech that was attributed to the unnamed commanders:

-

“The Romans had already learned of these splendid [Samnite] accoutrements, and their generals had taught them that a soldier should be rough to look on, unadorned with gold and silver but [rather] putting their trust in iron and courage: indeed. [gold and silver] were more truly spoils than arms, shining bright before a battle but losing their beauty in the midst of blood and wounds. Manhood, they said, was the adornment of a soldier; all those other things went with the victory, and a rich enemy was the prize of the victor, however poor”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 40: 5-7).

It is only at this point that we learn that:

-

“Papirius led them into battle. He took up his own post on the right, and committed the left to the master of the horse [C. Junius Bubulcus Brutus]. From the first moment, there was a mighty struggle with the enemy, and a struggle no less sharp between Papirius and Junius to decide which wing [of the Roman army] would inaugurate the victory”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 40: 7-9).

As things turned out:

-

“... Junius was the first to make an impression on the Samnites. With the Roman left, he faced the enemy's right, where [the Samnites] had consecrated themselves, as their custom was, and for that reason were resplendent in white [linen] tunics and equally white [silver] armour. Declaring that he offered up these men in sacrifice to Orcus [a god of the underworld], Junius charged, threw their ranks into disorder, and clearly made their line recoil”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 40: 9-11).

Here we learn that the white linen tunics of the men on the Samite right wing indicated that they had consecrated themselves in some way. Henk Versnel (referenced below, at p. 407) observed that, in the Roman ‘devotio’, a Roman general would:

-

“... consecrate himself in the literal sense of the word by ... [surrendering] his life into the possession of the gods [in return for victory, thereby making] himself ‘sacer’.”

Stephen Oakley, citing Versenl, observed that:

-

“... Junius, in a grim jest, pronounces that he will do the sacrificing [to Orcus], on behalf of the Romans.”

This again seems odd: one would have expected Papirius himself to have claimed the honour of facing the Samnite corps that was made up of men who had consecrated themselves.

Livy then returned to the theme of the competition between the Roman commanders: when Papirius saw Junius’ success, he:

-

“... cried [out to his men]:

-

‘Shall ... the dictator's division follow the attack of others [rather than] carry off the honours of the victory ?’

-

This fired the [rest of the Roman] soldiers with new energy; nor did ... the [legates display] less enthusiasm than the generals: [Marcus Valerius Maxiumus Corvus] on the right and [Publius Decius Mus] on the left, both men of consular rank, ... charged obliquely against the enemy's flanks. [The Samnites took flight and] the fields were soon heaped with dead soldiers and glittering [enemy] armour”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 40: 10-14).

In other words, there was significant tension between Papirius and his senior colleagues, and only they are recorded as making any significant contribution to the victory.

Nevertheless, whatever his actual contributions:

-

“... as decreed by the Senate, Papirius celebrated a triumph, in which by far the finest show was afforded by the captured [Samnite] armour. So magnificent was its appearance that the shields inlaid with gold were divided up amongst the owners of the moneychangers' booths, to be used in decking out the Forum. From this is said to have come the custom of the aediles adorning the Forum whenever the tensae ( covered chariots of the gods) were conducted through it. Thus:

-

✴the Romans made use of the splendid armour of their enemies to do honour to the gods; while

-

✴the Campanians, in consequence of their pride and in hatred of the Samnites, equipped the gladiators who furnished them entertainment at their feasts after this fashion, and bestowed on them the name of Samnites.”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 40: 15-18).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 524) observed that:

-

“This passing comment implies, perhaps correctly, that the Campani had served as allies [of the Romans] in this campaign.”

That, of course assumes that Livy had included this information in the correct place in his narrative.

Authenticity of Livy’s Account

I addressed above the fact that the putative lacuna after 9: 39: 4 makes it difficult to be sure whether or not the war described at 9: 40: 1-14 was a continuation of that at Longula. However, line 1 seems to indicate a new war and line 2 refer’s the the Samnites’ new and particular sumptuous armour. This, the likelihood is that this was, indeed a new war, in which case it is surprising that Livy did not describe its location and the circumstances that lead up to it.

The most difficult thing about Liv’s account of this was is the fact, as Edward Salmon (referenced below, at pp. 245-6) observed:

-

“The crushing victory that [Papirius] is said to have scored in [310/9 BC)], which is reflected in the fasti Triumphales, is recognised, even by Livy [see below], to contain features borrowed from his son’s victory ... in the Third Samnite War.”

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 176) expressed a similar opinion :

-

“The fame of both Cursor and his son, and the fact that they both [apparently] won great victories over the Samnites, seems to have produced some confusion between them. In particular, both are said to have faced special ‘consecrated’ armies of the Samnites, whose arms were adorned in gold and silver: the father in 310/9 BC and the son at Aquilonia in 293 BC. ... While [both] may have faced ‘consecrated’ armies ... , it seems rather more likely that the same motifs, perhaps originally independent of the annalistic tradition, were [later] attached to both.”

He detailed (at pp. 505-6) the points of close similarity between the two accounts, which also included that the same exhortation to the troops appeared in both of them. However, he concentrated here on the motif of the spoils won for Rome, and concluded (at p. 506) that:

-

“... Livy’s comment at 40: 16-7 ... should perhaps be referred to 293 rather than to 310/9 BC.”

As I discuss in my page on the Third Samnite War, I agree that all of these elements of Livy’s account belong in 293 BC.

Edward Salmon (referenced below, at p. 246) also pointed to another aspect of Livy’s account that arouses suspicion: Livy named:

-

“... no fewer than four of the most renowned generals of the Roman Republic as participants in [this glorious war]:

-

✴[the legates], M. Valerius Corvus and P. Decius Mus;

-

✴the dictator, L. Papirius Cursor; and

-

✴the master of horse, C. Junius Brutus.”

-

The victory, if not entirely fictitious, was, at most, merely a local success that helped maintain Roman diversionary pressure on the western borders of Samnium. Even so, it did not prevent the Samnites from striking at central Italy in the following year [see below].””

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 461) expressed a similar (albeit more nuanced) opinion :

-

“Even though Diodorus ignored Papirius’ campaign against the Samnites [in 310/9 BC], it would probably be an excess of scepticism to reject it out of hand; ... Nevertheless, the details of the fighting offered by Livy are unlikely to be sound... [and] it is possible that [they] are all unauthentic ...”

The obvious conclusion is that partisan sources that recorded Papirius’ achievements in 310/9 BC reproduced elements of surviving accounts of the victory and triumph of his homonymous son in 293 BC. Indeed, as is often pointed out, passages in Livy’s account of these later events betray his awareness of this possibility:

-

✴He started his account by observing that:

-

‘The triumph that [the younger Papirius] celebrated while still in office was a brilliant one for those days. ... The spoils of the Samnites attracted much attention; their splendour and beauty were compared with that of the spoils that his father had won [in 310/9 BC], which were familiar to all through their being used as decorations of public places”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 46: 2-4).

-

✴He noted that the younger Papirius dedicated the temple of Quirinus, presumably at the time of his triumph, and added:

-

“I do not find in any ancient author that it was he who had vowed this temple in the crisis of a battle, and certainly he could not have completed it in so short a time; it [must have been] vowed by his father when dictator [in 310/9 BC]: the son dedicated [the completed temple] when consul, and adorned it with the spoils of the enemy. There was such a vast quantity of these spoils that, not only were the temple and the Forum adorned with them, but they were distributed amongst the allied peoples and the nearest colonies to decorate their public spaces and temples”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 46: 7-8).

-

✴He had the younger Papirius urging his men not to be intimidated by the magnificence of the enemy armour by pointing out that:

-

“My father ... annihilated a Samnite army all in gold and silver [in 310/9 BC], and those [enemy] trappings brought more glory to the victors as spoils than ... to the wearers. It might, perhaps, be a special privilege granted to my name and family that the greatest efforts that the Samnites ever made should be frustrated and defeated under our generalship, and that the spoils that we brought back should be sufficiently splendid to serve as decorations for the public places of Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 39: 9-13).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 506) pointed out:

-

“There is no difficulty [in principal] in believing that two Papirii Cursores won important victories over the Samnites, but it is harder to have confidence that these two victories were won in such similar circumstances ... [Furthermore,] Livy’s awareness of the similarities only increases the suspicion that ... the details of one victory were merged with those of the other. If this did happen, then it is more likely that a large quantity of Samnite arms was brought to the city in 293 BC than in 310/9 BC, since:

-

✴the victory ...at Aquilonia was more celebrated and more important [in strategic terms];

-

✴the description of the triumph [that followed it] is one of the more reliable features of [Livy’s Book 10]; and

-

✴Livy’s testimony for that year is reinforced by that of Pliny [the Elder - see above].”

In other words, it is likely that much of Livy’s exuberant description of the elder Papirius’ victory over a consecrated Samnite army that was sworn to fight to the death can be safely discounted. This is bound to raise the question of whether Livy or his sources ‘borrowed’ details of the the victory of the younger Papirius in 293 BC in order to add colour to what was probably a much less impressive victory won by his father in 310/9 BC.

Events of 308 BC

According to Livy, in 308 BC:

-

“In recognition of his remarkable conquest of Etruria, Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus was continued in the consulship, and was given Publius Decius Mus for his colleague. ... The consuls cast lots for the commands, Etruria falling to Decius and Samnium to Fabius.”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 1-3).

Fabius in Samnium

Victory at Nuceria Alfaterna

Asterisks (Capua, Cumae, Suessula, Acerrae) = centres incorporated sine suffragio in Campania before 308 BC

Black squares (Suessa Aurunca, Cales) = Latin colonies founded near Campania before 308 BC

Underlined (Neapolis, Nola) = Campanian centres allied to Rome before 308 BC

According to Livy, Fabius’ first campaign took place in Campania. Soon after his re-election, he:

-

“... marched against Nuceria Alfaterna ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 3).

Prior Events

We know from Diodorus Siculus that, in 317 BC:

-

“The inhabitants of Nuceria, which is called Alfaterna, yielding to the persuasion of certain persons, [had] abandoned their friendship for Rome and made an alliance with the Samnites, (‘Library of History’, 19: 65: 7).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 462) pointed out, once the Campanian city of Nola had fallen to Rome in 313 BC (as described on the previous page), Nuceria Alfaterna still still represented a significant threat to Rome’s allies in this region. It seems that, during Fabius’ second consulship in 310/9 BC, the Romans attempted one of their earliest-known naval attacks: according to Livy:

-

“... a Roman fleet, commanded by Publius Cornelius, whom the Senate had placed in charge of the coast, sailed for Campania and put into Pompeii. From there the sailors and rowers set out to pillage the territory of Nuceria. Having quickly ravaged the nearest fields, from which they might have returned in safety to their ships, they were lured on ... by the love of booty ... While they roamed through the fields, nobody interfered with them, though they might have been utterly annihilated; but as they came trooping back, ... the local farmers overtook them not far from the ships, stripped them of their plunder, and even killed some of them; those who escaped the massacre were driven, a disordered rabble, to their ships”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38 2-4).

See Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 483) for the candidates for the identity of this naval commander.

Fabius’ Victory

According to Livy, Fabius rejected:

-

“... the overtures of peace [made by Nuceria Alfaterna] because its people had declined [peace] when it had been previously] offered to them. [Instead]. he laid siege to the place and forced it to surrender”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 3).

With the submission of Nuceria Alfaterna, Roman control of Campania was complete.

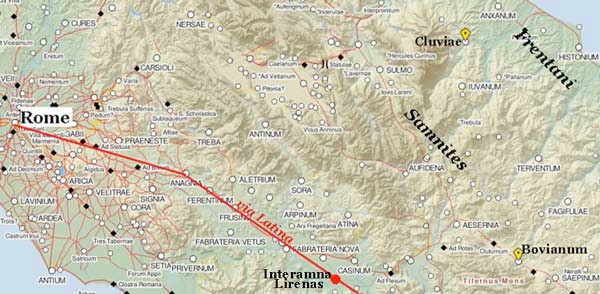

Campaigns Against the Samnites, Marsi and Paeligni

According to Livy, immediately after the submission of Nuceria Alfaterna:

-

“A battle was fought with the Samnites, in which the enemy were defeated without much difficulty. Indeed, the engagement would not have been remembered but for the fact that it was the first time that the Marsi had made war against the Romans. The Paeligni, who imitated the defection of the Marsi, met with the same fate”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 4-5).

Diodorus Siculus had a different version of this encounter: when Charinus was archon at Athens (i.e. in 308-7 BC):

-

“In Italy, the Roman consuls went to the aid of the Marsi, against whom the Samnites were making war. [They] were victorious in the battle and killed many of the enemy”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 44: 8).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 530) observed that Livy was probably correct to claim that the Romans fought against the Marsi at this time, while:

-

“There can be little doubt that Diodorus was in error [when he claimed that the Romans were protecting the Marsi from the Samnites].”

Diodorus was probably also in error when he claimed that both consuls engaged with the Samnites at this time: although Livy does not specifically name the Roman commander, this engagement:

-

✴followed on from Fabius’ victory at Nuceria Alfaterna, and

-

✴was followed by the observation that

-

“Decius, the other consul, was also successful in war”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 5).

Thus, we might reasonably assume (with, for example, Stephen Oakley, referenced below, 2005, at p. 532), that Livy attributed it to Fabius.

Livy makes it clear that this was the first time that the Marsi (and by implication, the neighbouring Paeligni, had engaged in hostilities with Rome. Both tribes bordered on northern Samnium, and it is interesting to note that, in 310/9 BC, the Samnites had considered whether they should:

-

“... march forthwith into Etruria, through the countries of the Marsi and the Sabines”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38: 4-8);

in order to reinforce the Etruscan army that was about to engage with the Romans. Given the strategic importance of the Marsi and Paeligni to both the Romans and the Samnites, we might reasonably assume that:

-

✴the Samnites had incited and aided their respective rebellions; and

-

✴the consequent battles took place on their respective territories.

Although both tribes were easily defeated, they did not apparently agree treaties with Rome until 304 BC (as described in my page ...).

Campaign at Allifae (307 BC)

The Samnite centre at Allifae, which occupied a strategic position in valley of the Volturnus (see the map below), has already appeared twice in Livy’s account of the war:

-

✴At the start of the war, in 326 BC. the Romans:

-

“... conducted a successful campaign in Samnium: three towns (Allifae, [the now-unknown] Callifae and Rufrium) fell into their hands, and the rest of the country was devastated far and wide ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 25: 4).

-

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 649) argued that:

-

“... the Romans did no more than raid in 326 BC and may not have tried to install a garrison.”

-

✴In 310 BC:

-

“... Caius Marcius Rutulus, captured Allifae from the Samnites by assault. Many forts and villages besides were either wiped out in the course of hostilities or came intact into the hands of the Romans”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38: 1).

-

Diodorus also recorded this engagement: he had both consuls campaigning in Etruria, until they received news that:

-

“ ... the Samnites ... were plundering with impunity those Iapyges who supported the Romans. The consuls, therefore, were forced to divide their armies; Fabius remained in Etruria, but Marcius, setting out against the Samnites, took the city Allifae by storm and freed from danger those of the allies who were being besieged”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 35: 1-2).

If Allifae did indeed fall into Roman hands in 310 BC, then the Samnites soon recovered it: according to Livy:

-

“The proconsul Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus fought a pitched battle with the army of the Samnites near the city Allifae. The result was decisive, for the enemy were routed and driven into their camp, which they only managed to hold because there[was] very little daylight left. ... The next day, before dawn, they began to surrender. The Samnites among them bargained to be dismissed in their tunics; all these were sent under the yoke. The allies of the Samnites were protected by no guarantee, and were sold into slavery ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 42: 6-8).

However, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 25) suggested that the Romans gained permanent control of this part of the valley of the Volturnus only at the end of the Third Samnite War (298 - 290 BC).

Hernician War (307 - 306 BC)

Green dots (Anagnia and Frusino) = rebels in the Hernician War

Yellow dots (Aletrium, Ferentinum, Verulae) = non-combatants in the Hernician War

As already discussed, the Hernici had submitted to Rome in 358 BC, and part their territory in the upper Sacco valley was confiscated for viritane citizen settlement and designated as the Poblilia voting district. From this point, although the Hernici retained their independence, they did so under the hegemony of Rome.

Thus, it was a serious matter when (according to Livy) the Romans discovered that Hernician soldiers had been serving in a Samnite army that had surrendered to them at Alifae in 307 BC. For this reason, the captured Hernici were separated from the other prisoners-of-war and:

-

“... sent to the Senate in Rome ... There, an enquiry was held as to whether they had been conscripted or had fought voluntarily for the Samnites against the Romans. They were then parcelled out amongst the Latins to be guarded. [In the following year], the new consuls, Publius Cornelius Arvina and Quintus Marcius Tremulus, ... [initiated] fresh action, [which] the Hernici resented. The people of Anagnia assembled a concilium populorum omnium (council of all the Hernician people) except for those of Aletrium, Ferentinum and Verulae, [at which, the assembled rebels] declared war on Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 42: 8-11).

In response, while Cornelius remained in Samnium, Marcius was sent to deal with:

-

“The new enemies (for, by this time, the Romans had declared on the men of Anagnia and other Hernici) ... [These rebels], having lost three camps in the space of a few days, negotiated a truce of 30 days so that they could send envoys to the Senate in Rome ... The Senate sent them back to Marcius, having passed a resolution empowering him to deal with them as he saw fit. He received their ... unconditional surrender”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 43: 2-7).

After further activity in Samnium:

-

“Marcius returned to Rome, which he entered in a triumph over the Hernici. An equestrian statue was decreed to him and erected in front of the temple of Castor in the Forum”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 43: 24).

The ‘fasti Triumphales’ record that, in this year, Marcius was awarded a triumph ‘over the Anagnini and Hernici’.

Incorporation of Anagnia

Livy noted that, after the Roman victory:

-

“Their own laws were restored to the three Hernican peoples of Aletrium, Verulae, and Ferentinum [who had remained loyal throughout the war], because they preferred them to Roman citizenship ... [However], the people of Anagnia and the others that had borne arms against Rome were:

-

✴admitted to citizenship without voting right;

-

✴prohibited from holding councils; ... and

-

✴allowed no magistrates other than those who had charge of religious rites”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 43: 24).

In other words, Aletrium, Verulae, and Ferentinum retained their nominal independence under Roman hegemony, but the people of Anagnia and other Hernici who had joined their rebellion were incorporated into the Roman state

Frusino

Our surviving sources link the town of nearby Volscian town of Frusino to this conflict:

-

✴Following his account of Roman activity in Samnium in 306 BC, Diodorus Siculus recorded that:

-

“[The Romans] declared war on the Anagnitae, who were acting unjustly, and, taking Frusino, they distributed the land”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 80: 4).

-

✴Livy recorded that:

-

“The Frusinonians were fined a third part of their lands [in 303 BC], because it was discovered that they had incited the Hernici to rebel [three years before]; and the heads of that conspiracy ... were beaten with rods and beheaded”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 1: 3).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 557 and note 1) suggested that:

-

“... the easiest interpretation of the evidence is that Frusino revolted in 307-6 BC and was captured by Marcius in 306 BC, but that its punishment was effected only after the Samnites had made peace [in 304 BC. If so, then] Diodorus will have merged the narrative of several years into one ...”

Fall of Bovianum (306 - 304 BC)

According to Livy, in 306 BC, when Marcius was engaged in the suppression of the revolt at Anagnia (above), the Samnites took:

-

“Calatia and Sora with their Roman garrisons ... , and the captured soldiers were treated with shameful rigour. Accordingly, Publius Cornelius was dispatched in that direction with an army”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 43: 1).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 577) argued that Livy’s ‘Calatia’ was actually Caiata, in the Monti Trebulani northeast of Capua, and (at p. 576) that this was probably the base from which they raided the ager Falernus in Campania in 305 BC.

According to Livy, in order to deal with this Samnite incursion, the consuls of 305 BC, Lucius Postumius Megellus and Tiberius Minucius Augurinus, were:

-

“... dispatched into Samnium in different directions, Postumius marching on Tifernum and Minucius on Bovianum” (‘History of Rome’, 9: 44: 6).

Livy had conflicting sources for the first phase of the battle, but it is clear that the two consular armies subsequently combined at Postumius’ camp at Bovianum:

-

“... there, the two victorious armies assailed the enemy... and overwhelmingly routed them, capturing 26 standards, as well as Statius Gellius, the commander of the Samnites, and many other prisoners... On the following day, they embarked on the siege of Bovianum: on its capture, which quickly ensued, the consuls crowned their glorious achievements with a triumph. ... [Also] in that year, Sora, Arpinum and Cesennia were won back from the Samnites, [and] the great statue of Hercules was set up and dedicated on the Capitol”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 44: 1-16).

Diodorus Siculus gave a very similar account:

-

“... since the Samnites were plundering [the ager Falernus], the consuls took the field against them, and, in the battle that followed, the Romans were victorious. They took 20 standards and made prisoners of more than 2,000 soldiers. The consuls at once took the city of Bola, but Gellius Gaius, the leader of the Samnites, appeared with 6,000 soldiers. A hard fought battle took place in which Gellius himself was made prisoner: most of the other Samnites were cut down, but some were captured alive. The consuls, taking advantage of such victories, recovered those allied cities that had been captured: Sora, Harpina, and Serennia”, (‘Library 0f History”, 20: 90: 3-4).

The putative triumph of Postumius and Minucius is only mentioned by Livy (above). However, he also noted that:

-

“Some writers state that Minucius ... was severely wounded and died after being carried back to his camp. They add that Marcus Fulvius was made suffect consul in his place, and that it was he who ... captured Bovianum”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 44: 15).

The ‘fasti Triumphales’ record that it was M. Fulvius Curvus Paetinus alone who triumphed as consul over the Samnites in 305 BC. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 577 and note 5) argued that:

-

“Since there is no obvious motive for the invention of a suffect consulate and a triumph for Fulvius, we should accept the tradition that he took Bovianum. If so, then:

-

✴Livy erred in saying that both consuls triumphed; and

-

✴his picturesque battle [above] would have been fiction: Minucius was already dead.”

Renewal of the Treaty (304 BC)

In 304 BC, the Samnites sued for peace. Livy’s description of this humiliation of the Samnites is oddly low-key:

-

“[In 304 BC], the Samnites, whether seeking to end or simply to postpone hostilities, sent envoys to Rome to sue for peace. The Romans’ answer to their humble supplications was that, if they had not frequently sought peace [in the past] while preparing for war, a treaty could have been arranged by mutual discussion: as it was, since [their] words had hitherto proved worthless, the Romans would have to take their stand on facts. P. Sempronius, the consul, who was someone whom they would be unable to deceive as to whether [they really wanted] peace or war, would shortly be in Samnium with an army. After a thorough investigation, he would report his findings to the Senate and, on his leaving Samnium, their envoys might attend him. The Roman army [duly] marched all over Samnium; the people were peaceable and furnished the army liberally with supplies. Accordingly, in that year, the ancient treaty was restored again to the Samnites”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 45: 1-4).

The ‘fasti Triumphales’ record that P. Sulpicius Saverrio, one of the consul of this year, triumphed over the Samnites, bit there is no other record of this triumph and Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 588 pointed out that, after the successes of the previous year, there would have been little for Sulpicius to do in Samnium.

Read more:

M. Wilson, "The Needed Man: Evolution, Abandonment, and Resurrection of the Roman Dictatorship" (2017) thesis of City University of New York

P. Camerieri, “Il Castrum e la Pertica di Fulginia in Destra Tinia”, in:

G. Galli (Ed.), “Foligno, Città Romana: Ricerche Storico, Urbanistico e Topografiche sull' Antica Città di Fulginia”, (2015) Foligno, at pp. 75-108

J. C. Yardley (translation) and D. Hoyos (introduction and notes), “Livy: Rome's Italian Wars: Books 6-10”, (2013), Oxford World's Classics

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume IV: Book X”, (2007) Oxford

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV Secolo a.C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume III: Book IX”, 2005 (Oxford)

S. Sisani, “Lucius Falius Tinia: Primo Quattuorviro del Municipio di Hispellum”, Athenaeum, 90.2 (2002) 483-505

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume II: Books VII and VIII”, (1998) Oxford

T. Cornell, “The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (ca. 1000-264 BC)”, (1995) London and New York

A. Drummond, “The Dictator Years”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 27:4 (1978), 550-72

H. S. Versnel, “Two Types of Roman Devotio”, Mnemosyne (4th Series), 29:4 (1976) 365-410

W. Harris, “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

E. Salmon, “Samnium and the Samnites’, (1967) Cambridge

W. B. Anderson, “Contributions to the Study of the Ninth Book of Livy”, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 39 (1908) 89-103

Return to Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)