Black asterisks = centres incorporated sine suffragio after the Latin War

Red squares = Roman citizen colonies

Black squares = Latin colonies

Prior Events

Changing Balance of Power on the Roman/Samnite Border

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 639) observed, by 327 BC:

-

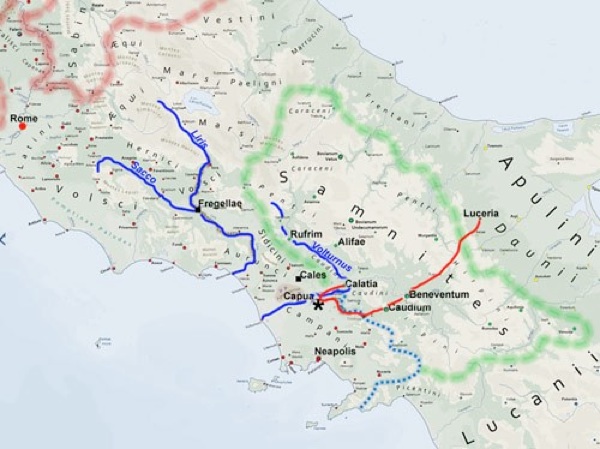

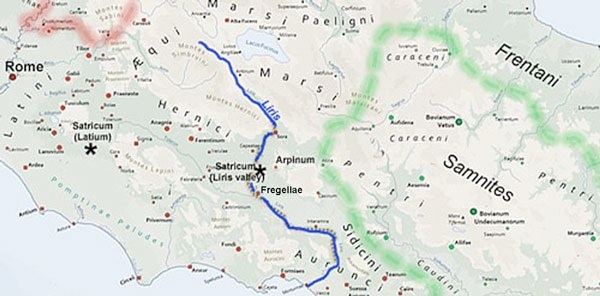

✴the Romans’ incorporation of Capua and its satellite towns from 338 BC had greatly strengthened Roman power in northern Campania; and

-

✴subsequent victories over the Aurunci, the Ausones and the Sidicini had been followed by the foundation of Roman colonies at Cales (in 334 BC) and Fregellae (in 328 BC) and the incorporation of Privernum (in 329 BC).

He also pointed out (at p. 638) that the Samnites had been distracted in the period 334-1 BC by the gains on their southern border made by made by Alexander of Epirus, initially as a mercenary acting for the Greeks of Tarentum (who were threatened by the Lucanians and Apulians) but ultimately on his own behalf, and Samnite fears must have increased when the Romans made some sort of treaty with him in 332 BC (‘History of Rome’, 8: 17: 9-10). Alexander’s murder in 331 BC removed the threat to both Tarentum and the Samnites. From this point, the Samnites were once more able to confront the threat that the Romans represented on their southwestern border.

Outbreak of the Neapolitan War (328 - 7 BC)

The Greek city-state of Neapolis (modern Naples) must have been concerned when, in 338 BC, the Romans incorporated Capua, Cumae and Suessula (followed by Acerrae in 332 BC). When the Samnites renewed interest in their border with Campania after the murder of Alexander in 331 BC, the Neapolitans probably realised that they would have to choose between the hegemony of the Romans or that of the Samnites.

Immediate Cause of the Roman’s War with Neapolis

According to Livy, the conflict began in 328 BC when a Greek city called Palaepolis, which was:

-

“... not far from where Neapolis now stands ... committed numerous hostile acts against the Romans who inhabited the ager Campanus and the ager Falernus”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 22: 7).

In the parallel account by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, the conflict began:

-

“When [the Romans received] repeated charges and complaints from the Campanians against the Neapolitans ... ”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 15: 5: 1).

The apparent difference between Livy’s ‘Romans who inhabited the ager Campanus and the ager Falernus’ and Dionysius’ Campanians need not concern us since, by this time:

-

✴the people of norther Campania (including Capua) had been incorporated as Roman citizens without voting rights; and

-

✴the ager Falernus had been confiscated and distributed to Roman citizens (for whom the Falerna tribe would be established in 318 BC).

More problematic is Livy’s reference to ‘Palaepolis’, a city that is known only from this passage and a related entry in the fasti Triumphales (see below). Livy explained that, at the time of these hostilities, Palaepolis and Neapolis were:

-

“... inhabited by one people, [and the nearby Greek colony of Cumae had been] their mother city”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 22: 5).

Interestingly, Dionysius never mentioned Palaepolis at any point in the surviving and extensive fragments his account of this war. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 643) argued that:

-

“It is absurd to believe that, in 327 BC, there was [an independent] sovereign state called Palaepolis [so close to Neapolis] ...”

He suggested (at p. 644) that:

-

“The best way of accounting for the surviving [linguistic, literary and archeological] evidence is to hold that the Neapolitan populus did indeed occupy two sites:

-

✴one was the site of the city of Neapolis itself; and

-

✴the other was on the height known today as Pizzofalcone, ... [which would have offered] a good defensive position. ...

-

Livy’s account may be accepted if we adopt this interpretation of the name Palaepolis and argue that [Livy’s sources only] recorded fighting [at Palaepolis] ... ”

In short, it seems that the Romans’ potentially hostile interactions with the Neapolitans began when the people of northern Campania complained to them about Neaploitan hostilities on their territory.

Roman Embassy to Neapolis

According to Livy, in 327 BC:

-

“When L. Cornelius Lentulus and Q. Publilius Philo (for the second time) were consuls, fetials were dispatched to Palaepolis to demand redress [for their recent hostile acts in Campania]. When [the fetials] received a spirited answer from the Greeks (a race more valiant in words than in deeds), the [Roman] people acted upon a resolution of the Senate and commanded that war be made upon Palaepolis ..”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 22: 8-10).

A much more informative account of this embassy is found in surviving fragments of the now-lost Book 15 of the ‘Roman Antiquities’ of Dionysius of Halicarnassus: on receiving complains from northern Campania of Neapolitan hostilities there:

-

“... the Senate voted to send ambassadors to [the Neapolitans] to demand that they should do no wrong to the subjects of Rome. Rather, they should act justly and settle any differences between them ... by negotiation ... [The Senate also instructed that], if the ambassadors were able to gain the favour of the influential Neapolitans, they [should use them in order to instigate the defection of] Neapolis from the Samnites to the Romans”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 15: 5: 1).

Interestingly, Dionysius made no mention of fetials sent to Neapolis.

Other Embassies to Neapolis

Dionysius is our only surviving source for the fact that other ambassadors soon arrived at Neapolis to make the case for continuing Samnite hegemony:

-

“It chanced that, at this same time, ambassadors were sent to Neapolis from Tarentium ... and by [the Osco-Campanian city of] Nola ... to ask the Neapolitans not to make an agreement with the Romans or their subjects but instead to retain their friendship with the Samnites.

These ambassadors promised that:

-

“If the Romans should make this [refusal] their pretext for war, the Neapolitans should not be alarmed ... by the strength of the Roman. ... Rather, they should stand their ground and fight as befitted Greeks, relying on:

-

✴their own army and the reinforcements that would come from the Samnites; and

-

✴the large and excellent naval force that the Tarentines would send in the event that their own naval force proved to be insufficient ..., (‘Roman Antiquities’, 15: 5: 2-3).

The Samnites themselves then addressed the Neapolitan popular assembly in order to present their case themselves:

-

“[They] recounted their own services [to the Neapolitans and] made many accusations against the Romans, charging them with being faithless and treacherous ... [They then] made some remarkable promises to the Neapolitans, if they would enter the war: they would:

-

✴send an army ... as large as the Neapolitans required to guard their walls;

-

✴furnish marines for their ships as well as all the rowers; and

-

✴meet all the expenses of the war, not only for their own armies but also but for the others.

-

Furthermore, when the Neapolitans had repulsed the Romans, the Samnites would:

-

✴recover Cumae from the Campanians (who had occupied Cumae two generations earlier, after expelling the Cumaeans);

-

✴restore their lost possessions to those of the surviving Cumaeans who had been driven out of their own city and received by the Neapolitans ... ; and

-

✴grant to the Neapolitans themselves some of the non-urban land that was then in Campanian hands ... , (‘Roman Antiquities’, 15: 6: 3-4).

Dionysius then gave an interesting account of the debate between the Neapolitan factions:

-

“The element among the Neapolitans that was reasonable and able to foresee ... the disasters that would come upon the city from the war wished to remain at peace [with Rome]; but, the element that was fond of innovations and sought the personal advantages to be gained from turmoil joined forces [to press for] war. There were mutual recriminations and skirmishes, and the strife was carried to the point of hurling stones, but, in the end, the worse element overpowered the better, so the Roman ambassadors returned home without having accomplished anything. [This was thus Livy’s ‘received a spirited answer from the Greeks’]. For these reasons the Roman Senate resolved to send an army against the Neapolitans”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 15: 6: 7).

Roman Preparations for War with Neapolis (327 BC)

According to Livy:

-

“When L. Cornelius Lentulus and Q. Publilius Philo (for the second time) were consuls ... :

-

✴the war with the [Neapolitans] was assigned to Publilius; and

-

✴Cornelius ... was ordered to be ready in case the Samnites should take the field: since it was rumoured that [the Samnites] were only waiting to bring up their army the moment the Campanians began a revolt, [the border of Campania and Samnium] seemed to be the best place for Cornelius’ camp”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 22: 8-10).

In due course:

-

“Both consuls informed the Senate that there was very little hope of peace with the Samnites:

-

✴Publilius reported that 2,000 soldiers from Nola and 4,000 Samnites had forced entry into Palaepolis, under compulsion from the people of Nola rather than by the request of the Greeks themselves.

-

✴Cornelius reported that:

-

•the Samnite magistrates had proclaimed a military levy;

-

•the whole of Samnium was up in arms; and

-

•the Samnites were openly urging the neighbouring cities of:

-

-Privernum, [which the Romans had incorporated without citizenship in 329 BC];

-

-Fundi [which the Romans had incorporated without citizenship in 338 BC and rebelled briefly in 329 BC]; and

-

-Formiae [which the Romans had incorporated without citizenship in 338 BC];

-

to join them.

-

In view of these facts, the Senate ... voted to send ambassadors to the Samnites before [finally deciding whether it was time to declare war on them] ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 23: 1-3).

Roman Embassy to the Samnites (327 BC)

According to Livy, the Roman ambassadors:

-

“... received a defiant answer from the Samnites, who] went so far as to accuse the Romans of improper conduct and vigorously denied the Roman allegations against them, asserting that:

-

✴they had given no advice or aid to the Neapolitans]; and

-

✴they had not encouraged the people of either Fundi or Formiae to defect ...

-

On the other hand, they could not hide the outrage of their nation that the Romans had:

-

✴rebuilt Fregellae, which they [i.e., the Samnites] had captured from the Volsci and destroyed; and

-

✴founded a colony in [what they now regarded as] Samnite territory, which the Roman colonists actually called ‘Fregellae’.

-

This was an insult and an injury and, if the Romans did not redress it [presumably by abandoning the colony], then they would do their utmost to remove them”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 23: 4-10).

The Roman ambassadors suggested independent arbitration:

-

“... to which the Samnite spokesman replied:

-

‘Why do we beat about the bush? Our differences, Romans, will be decided [by neither negotiation nor] arbitration, but by:

-

✴the Campanian plain, where we must meet in battle;

-

✴the sword; and

-

✴the fortunes of war.

-

Let us therefore camp, facing each other, between Suessula and Capua, and settle the question of whether the Samnites or Romans are to govern Italy. The Roman legates having replied that they go not where the enemy summoned them but where their generals led them ...’”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 23: 8-10).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at pp. 657-8) addressed the problem of the lacuna in the surviving manuscripts at the end of 8: 23: 10 and suggested that a significant amount of information (perhaps, for example, a report to the Senate) has been lost.

Dionysius (in another surviving fragment of the now-lost Book 15) also recorded that:

-

“The Romans, learning that the Samnites were assembling an army, first sent ambassadors to them. They complained that:

-

‘In spite of your treaty obligations ... ;

-

✴this last year, when the Neapolitans were afraid to declare war against us, you:

-

•devoted all your efforts to encouraging (or rather compelling) them to do so;

-

•are paying all the expenses; and

-

•are occupying their city with your own forces; and

-

✴now, you are :

-

•preparing an army ... and have resolved to lead it against our colonists [at Fregellae]; and

-

•inviting the Fundans and Formians, as well as some others to whom we have granted citizenship, to join you in this endeavour.

-

Although you were thus openly and shamelessly violating our treaty of friendship and alliance, we, nevertheless ... decided to send an embassy to you, trying negotiations before taking action. The things that we ask you to do [in reparation] are these: we wish you:

-

✴to withdraw the military assistance that you have sent to the Neapolitans; and

-

✴desist from:

-

•sending out any army against our colonists; and/or

-

•inviting our subjects to to participate in your encroachments.

-

If some of you have been doing these things ... on their own initiative, we ask you to surrender them to us for trial. If we gain these demands, we are content; but if we fail to obtain them, we call to witness the gods and lesser divinities by whom you swore in making the treaty, and we have come bringing with us the fetials for this purpose.’

-

[The] Samnites delivered the following reply ... :

-

✴‘It is true that there are some of our troops in Neapolis, ... [but]:

-

•this city .... [has been] our friend and ally ... [for] two generations, and yet] you enslaved it without cause; and

-

•.... even in these circumstances, it is not the Samnite State that has wronged you, ... [since the Samnite force at Neapolis is made up of]

-

-some men who are connected by private ties of hospitality ... and friends of the Neapolitans who are aiding that city of their own free will; and

-

-... [others who] are serving as mercenaries.

-

✴As for stealing away your subjects, we have no need of such a course; for even without the Fundans and Formians, we are quite able to succour ourselves if we are driven to the necessity of war.

-

✴The preparation of our army in readiness is not the act of those who are intending to rob your colonists of their possessions, but rather of those who intend to keep their own possessions.

-

We ask you in turn, if you wish to pursue the just course, to retire from Fregellae, which, after we had conquered it in war a short time ago (and this is the most legitimate title to possession) you unjustly appropriated and now hold for the second year. If we on our side gain these points, we shall not feel that we are wronged in any respect”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 15: 7:1 - 8:4).

It seems that both Livy and Dionysius dated this embassy to 327 BC:

-

✴Livy certainly placed it in the year in which Publilius and Cornelius were consuls; and

-

✴as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 647) pointed out, in the case of Dionysius, this is indicated by a later reference to Cornelius (see below) and by his reference at the end of the passage discussed above that the Fregellae, which the Romans had taken in 328 BC, was in their hands for the second year.

Declaration of War with the Samnites (327 or 326 BC)

According to Dionysius, when the Samnites countered the Roman’s demand for reparations with similar demands of their own:

-

“... the Roman fetial replied:

-

‘Now that you Samnites have so openly violated your oaths to maintain the peace, there is no longer anything to prevent [a lacuna follows - presumably there was nothing to prevent a Roman declaration of war]. [Do not try to] lay the blame on the Roman people, because they have done everything according to the sacred and time-honoured laws ...’

-

As he was about to depart, he drew his mantle down over his head and, raising his hands toward heaven, as is the custom, he uttered prayers to the gods:

-

‘If the Roman people, having suffered wrongs at the hands of the Samnites and [having been unable to secure reparations], should proceed to war, may the gods ... inspire them with good counsels and grant that her undertakings ... may prove successful. However, if they are guilty of committing any violation of the oaths of friendship or of inventing false grounds for hostility, may ... their undertakings fail.’", (‘Roman Antiquities’, 15: 9).

It is clear that Dionysius regarded the fetials’ pronouncement as a provisional declaration of war because he continued:

-

“When [the Samnites and Romans] had departed from the assembly ... :

-

✴the Samnites expected that the Romans would move rather slowly, as it is their custom to do when they are about to begin war; and

-

✴the Romans believed that the Samnite army would soon proceed against their colonists in Fregellae.

-

[However, they each had their expectations confounded]:

-

✴the Samnites, while making their preparations and delaying, lost the opportunities for action, whereas

-

✴the Romans, having everything prepared and in readiness, as soon as they learned the answer given to their ambassadors, voted for war and sent out both consuls. Before the enemy was aware that [the consuls] had sent out, both:

-

•the newly-enrolled force; and

-

•the one that was [already] wintering among the Volscians, under the command of Cornelius;

-

were inside the Samnite borders", (‘Roman Antiquities’, 15: 10).

This chronology does not agree with that assumed by Livy, who noted that, as the end of the consular year approached (after the Roman embassy to the Samnites but before their formal declaration of war on the Samnites):

-

“Publilius [had established his camp in] a favourable position between Palaepolis and Neapolis. [Since] the time drew near for the elections, and it was not to the advantage of the state that Publilius ... should be called away from ... [Neapolis],... the Senate [arranged for] the tribunes to propose a popular enactment, providing that [he] should continue the campaign as proconsul until the [Neapolitans] had been conquered. [Since the Senate was also reluctant to recall] Cornelius, who had already entered Samnium, ... they sent him a letter directing him to name a dictator for conducting the elections”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 23: 11-13).

After:

-

✴ a long passage on the difficult elections that resulted in the election of the consuls C. Poetelius Libo Visolus and L. Papirius Cursor(see below);

-

✴and a digression at 8: 24 (in which he dealt with the death of Alexander of Epirus);

Livy recorded that Poetelius and Papirius:

-

“... sent fetials, as commanded by the People, to declare war on the Samnites, ... [and] began ... to prepare for it on a much greater scale in every respect than they had done against the [Neapolitani]”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 25: 2).

The harmonisation of these two chronologies is still debated: for example:

-

✴Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at pp.648-9) suggested that Dionysius’ record that war on the Samnites was declared in 327 BC was preferable; while

-

✴John Rich (referenced below, at p. 221 and note 143) argued that, pace Oakley:

-

“Dionysius’ indications should probably be interpreted as placing both the [Roman embassy to the Samnites] and the ensuing war vote in 326 BC.”

As I indicated above, it seems to me that both Dionysius and Livy placed this embassy in 327 BC. Amazingly, the presence of lacunae in both accounts (as they now survive) mean that we do not actually know when either of them placed the formal declaration of war. However, we might usefully look again at Dionysius’ remark that:

-

“Before the [Samnites were] aware that [the consuls] had sent out [from Rome], both:

-

✴the newly-enrolled force; and

-

✴the one that was [already] wintering among the Volscians, under the command of Cornelius;

-

were inside the Samnite borders", (‘Roman Antiquities’, 15: 10).

As we shall see, in 326 BC, Publilius actually remained as proconsul at Neapolis, where he presumably retained his army. Thus, the most obvious reading of this passage by Dionysius is that the Romans began their preparations for war during the long interregum, so that, immediately on their election, the new consuls, Poetelius and Papirius, formally declared war on the Samnites and left Rome, with:

-

✴one of them taking over command of Cornelius’ army; and

-

✴the other commanding a new army that had already been recruited.

First Phase of the Samnite War (326 - 321 BC)

Election of the Consuls of 326 BC

As we have seen, Livy recorded that, since neither of the consuls of 327 BC was able to leave his army in order to hold the elections for their successors, the Senate instructed one of them, Cornelius, to name a dictator comitiorum habendorum caussa (for holding elections). He:

-

“... named M. Claudius Marcellus, who named Sp. Postumius as his master of the horse. However, [Marcellus] did not hold the comitia because the regularity of his appointment was called in question. The augurs were consulted, and announced that the procedure appeared faulty”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 23: 11-13).

According to Livy:

“this sentence the tribunes by their accusations made suspect and infamous; for the flaw, as they pointed out, could not easily have been discovered, since the consul rose in the night and appointed the dictator in silence, neither had the consul written to anyone [p. 93]regarding the transaction, whether officially or5 privately, nor was there a single mortal living who could say that he had seen or heard a thing that would bring to naught the auspices; [16] nor yet could the augurs have divined, as they sat in Rome, what obstacle the consul had met with in the camp. was there anyone, they would like to know, who could not see that the plebeian standing of the dictator was the thing which had seemed irregular to the augurs? [17] These and other objections were made by the tribunes to no purpose;

Livy then recorded that:

-

“... the state at length reverted to an interregnum and, after the comitia had been repeatedly postponed on one pretext or another, the 14th interrex, L. Aemilius [Mamercinus Privernas], finally procured the election of consuls”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 23: 17).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 662) observed that:

-

“All this amounted to another grave crisis in the [so-called] ‘Struggle of the Orders’, a crisis doubtless exacerbated by the threat of war with the Samnites.”

The identity of this 14th interrex, L. Aemilius Mamercinus, is possibly significant: as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 212) pointed out, Publilius (whose imperium had been extended into 326 BC) had:

-

✴served as Mamercinus’ master of horse in 335 BC and

-

✴shared the consulship with Tib. Aemilius Mamercinus (probably Lucius’ brother) in 339 BC.

This might suggest a political alliance between Publilius and the Aemilii Mamercini, in which case, Publilius might well have disrupted the electoral process to ensure that his favoured candidates were elected.

Livy identified the new consuls as:

-

“... C. Poetelius Libo Visolus and L. Papirius Mugillanus: in other annals, I find the name of [Paprius] Cursor”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 23: 17).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 664) reasonably argued that the cognomina Mugillanus and Cursor belonged to the same L. Papirius. As discussed further below, it seems likely that Papirius’ election as consul in 326 BC marked the start of a close relationship with Publilius, who (as we have seen) continued in office as proconsul.

-

[They soon] received new and ... quite unexpected help: the Lucanii and Apulii. who had had no previous dealings with the Romans, put themselves under their protection and promised arms and men for the war. They were accordingly received into a treaty of friendship”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 25: 2-3).

If Livy is correct here, then the Samnites, having lost their alliance with Neapolis to the Romans, now found that there were also other Roman allies on their southern and eastern borders. However, as we shall see, the putative alliances with the Lucanii and the Apulini seem to have been short-lived (if they existed at all).

Both consuls:

-

“... conducted a successful campaign in Samnium: three towns (Allifae, [the now-unknown] Callifae and Rufrium) fell into their hands, and the rest of the country was devastated far and wide ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 25: 4).

Thus, as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 649) pointed out:

-

“... it seems that the Romans were raiding the middle Volturnus valley ..., an area that they could have reached quite easily ... from their bases at Capua or Cales. [As we shall see], Allifae was back in Samnite hands by 310/9 BC at the latest, but this is hardly problematic: the Romans did no more than raid in 326 BC and may not have tried to install a garrison.”

According to Livy:

-

“ ... by taking up a favourable position between Palaepolis and Neapolis, Publilius ... [prevented the Samnites at Neapolis from sending reinforcements]. However, the time for the [consular] elections drew near and, since it would have been disadvantageous for Publilius ... to be called away from the prospective capture of the city, the Senate [arranged that he should continue in office as proconsul] until the Greeks had been conquered”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 23: 10-12).

He then described the dreadful plight of the Palaepolitani, since:

-

“... things were going on within their walls that were much more dreadful than the perils with which the [besieging Romans] threatened them; they were subjected to outrage ... and suffered all the horrors of captured cities, as if they were prisoners of their own defenders.. [For this reason, when they received a report that reinforcements were on their way from both the Tarentines and the Samnites:

-

✴they felt that they already had more Samnites within their city than they wanted; but

-

✴being Greeks, they looked forward to the coming of their fellow Greeks, the young men of Tarentum, to enable them to resist the Samnites and the Nolani, no less than their enemies, the Romans.

-

In the end, [when the Tarentine reinforcements had presumably failed to arrive], it appeared to them that surrender to the Romans was the least intolerable evil: [the Greek] Charilaus and [the Oscan] Nymphius, their principal citizens, took counsel together and arranged the part that each should play in order to bring this about”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 25: 5-9).

He described at length the subsequent ruse that allowed:

-

✴the Romans to enter it and expel the Nolani; while

-

✴the Samnites, who had already been tricked into breaking out of it:

-

“... returned to their homes, despoiled and destitute, a laughing stock not only to strangers but also to their own countrymen”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 26: 5).

Livy then acknowledged that he was :

-

“... aware of the other tradition, which ascribes the capture [of Palaepolis] to betrayal by the Samnites, but I have followed the authorities who are more deserving of credence; moreover, [the presumably favourable terms of the ] treaty with Neapolis (to which place the Greeks now transferred the seat of government) makes it more likely that they renewed the friendship voluntarily”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 26: 6).

It is likely that Livy or his sources were mistaken here, and that the seat of government had always been in the city in the plain. He acknowledged that some sources attributed the fall of Palaepolis to its betrayal by the Samnites, but he noted that:

-

“[The presumably favourable] terms of this treaty make it more likely that the Greeks [had not been forced to surrender, but had rather] renewed the friendship [with Rome] voluntarily”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 26: 6).

The existence of this treaty was confirmed by Cicero, who noted that:

-

“... a great part of the inhabitants of [Heraclea and Neapolis] preferred ... the freedom that they enjoyed under their own [treaties with Rome to Roman citizenship]”, (‘Pro Balbo’, 21, translated by Robert Gardner, referenced below, at pp. 649-51).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 685) observed that:

-

“This [treaty] will certainly have required [the Neapolitani] to furnish [the Romans with] ships, [which they did, for example, in 193 and 191 BC.]”

Finally, Livy noted that

-

“Publilius was decreed a triumph, since it was generally believed that the enemy had surrendered only because they had been broken by the siege [of Palaepolis]. Publilius had thus received two unprecedented distinctions:

-

✴an extension of his command, something that had never before been granted to any [serving consul]; and

-

✴a triumph after the expiration of his [extended] term”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 26: 6).

The ‘fasti Triumphales’ recorded that Q. Publilius Philo was the first proconsul to be awarded a triumph, in this case over the Samnites and the Palaepolitani (sic).

Events of the Dictator Year 325/4 BC

This was the second of the four so-called dictator years, which are discussed collectively in my page on Dictator Years (334/3; 325/4; 310/9; and 302/1 BC). They are so-called because some relatively late sources record:

-

✴a normal consular year (in this case, 325 BC Varronian), followed by;

-

✴a fictitious year (in this case, 324 BC Varronian), in which a dictator and his master of horse ruled without consuls.

Livy, who never recognised the existence of the fictitious consul-free dictator years, recorded the events of periods such as these in a single consular year: in this case, the year under discussion here is therefore designated as 325/4 BC. We might reasonably follow Livy in assuming that:

-

✴the consuls for this year were L. Furius Camillus (for the second time) and D. Junius Brutus Scaeva; and

-

✴as we shall see, when Camillus was incapacitated, his command passed to a dictator, L. Papirius Cursor, who appointed Q. Fabius Maximus Rullianus as his master of horse.

War with the Vestini

According to Livy, the Vestini rebelled in 325 BC. The consuls brought the matter before the Senate, who had been reluctant to address it since:

-

“... the race as a whole was fully equal to the Samnites in military power, since it included the Marsi, and the Paeligni and Marrucini, all of whom [would take the part of the Vestini, should they] be attacked. [However, despite these fears], the people voted a war against the Vestini, and this command was assigned by lot to Brutus”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 29: 4-7).

He devastated the territory and drove the Vestini back into their strongholds, two of which (the now-unknown Cutina and Cingilia) he destroyed. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 701) noted that this is the first time that the tribes of the Abruzzo had appeared in Livy’s work since 340 BC, when they had allowed the Romans passage into Samnium for their planned joint attack with the Samnites on Capua. Oakley argued that:

-

“... two interpretations of [the situation in 325 BC, as Livy described it] are possible: either

-

✴the Vestini, alone of these tribes, were not prepared to guarantee Roman armies passage and [therefore] had to be brought to heel; or

-

✴their defeat made it clear, to themselves and to the other tribes, that they should not try to resist the passage of Roman arms.”

War in Samnium

While Brutus was fighting the Vestini, Camillus marched into Samnium in order to prevent them from aiding the Vestini. However, according to Livy, soon after he arrived in Samnium, he:

-

“... became dangerously ill and was forced to relinquish his command; L. Papirius Cursor, who was by far the most distinguished soldier of the time, [took over his command] as dictator, ... with Q. Fabius Maximus Rullianus as his master of the horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 29: 8-9).

At this time, the young Fabius had featured only once before in Livy’s narrative (as curule aedile in 331 BC), but he was reach the consulship for the first of five times in 322 BC.

Papirius’ Feud with Fabius

Livy now introduced the main theme of his account of 325/4: Papirius and Fabius:

-

“... were a pair famous for the victories won while they were magistrates; but their quarrelling, which almost went the length of a mortal feud, made them more famous still”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 29: 10).

Fabius’ Offence

The scene was set when it became apparent that:

-

“The expedition into Samnium [had been] attended by ambiguous auspices ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 30: 1).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 707) explained:

-

“... the army had [apparently] set out without its being clear whether or not the auspices were favourable.”

Papirius had presumably taken over Camillus’ camp in or on the border of Samnium by the time that the problem was discovered, and was forced to return to Rome, leaving Fabius in command.

Livy recorded that:

-

“As Papirius was setting out for Rome ... to take the auspices afresh, he warned Fabius not to engage in battle with the enemy in his absence. However, when Fabius [subsequently] ascertained from his scouts ... that the enemy were ... [behaving] as if there had been not a single Roman in Samnium, ... he put the army in fighting trim and, advancing upon a [now-unknown] place they call Imbrinium, engaged in a pitched battle with the Samnites. This engagement was so successful that no greater success could have been gained, had [Papirius] been present; ... It is said that [20,000 Samnites] were killed that day”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 30: 2-7).

Livy now addressed the inconsistency that he had found in his sources for this incident:

-

“I find it stated by certain writers that Fabius fought the enemy twice while Papirius was absent, and twice gained a brilliant victory. {however],:

-

✴he oldest historians give only this single battle; and

-

✴in certain annals the story is omitted altogether”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 30: 7).

He then returned to the main narrative: he concluded that, whether after one or two engagements, Fabius:

-

“... found himself, after so great a slaughter, in possession of extensive spoils. He piled the enemy's arms in a great heap ... and burnt them:

-

✴this may have been done in fulfilment of a vow to one of the gods; or

-

✴if one chooses to accept the account of [the historian] Fabius (see below), it was done] in order to prevent Papirius from reaping the harvest of his [i.e. Fabius’] glory and inscribing his name on the arms or having them carried in his triumph.

-

Fabius sent the dispatch reporting the success to the Senate rather to [Papirius], which certainly suggests that he had no mind to share the credit with Papirius. At all events, [Papirius] so received the news that, while everyone else was rejoicing at the victory, he showed only signs of anger and discontent”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 30: 8-10).

And so, a feud was born.

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 696) observed that:

-

“Many (and perhaps most or all) of these details are likely to be the product of a process of elaboration that ... reached its peak with Livy, and it would be unwise to have confidence in any of them. Yet, it would be unwise entirely to reject the historicity of the quarrel.”

Livy’s reference to the historian Fabius almost certainly indicates Fabius Pictor, an ancestor of the offended in this narrative, whose history of Rome covered the period down to 217 BC: thus, as Oakley pointed out:

-

“... it cannot be the work of later annalists.”

Edward Bispham and Timothy Cornell (in T. C. Cornell, referenced below, 2013, Volume III, at p. 34, Fragent 17) concluded that details of this feud (including Fabius’ letter to the Senate) had probably been preserved in the family archive, and:

-

“ ... written up by Fabius Pictor, but [left] no record in the [state archives, which] would account for Livy’s comment that, in some annals, the whole incident was left out.”

Papirius’ Retribution

Fabius had committed at least two grievous offences: he had engaged the enemy while the auspices were uncertain; and (more importantly for what was to follow) he had ignored the explicit command of a dictator. Papirius wanted the death penalty and Rome was in crisis. Matters came to a head when:

-

“... the Roman people ... entreated and adjured [Papirius] to remit the punishment of Fabius for their sake. The tribunes, too, fell in with the prevailing mood and earnestly besought Papirius to allow for human frailty and for the youth of Fabius, who had suffered punishment enough. First [Fabius] himself and then his father, M. Fabius Ambustus, forgetting their previous animosity, threw themselves at Papirius’ feet and attempted to avert his anger”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 35: 1-3).

No one denied that Fabius was guilty as charged. However, Papirius probably had no choice but to agree to his reprieve. Thus, he pronounced:

-

“Live, Q. Fabius, more blest in this desire of your fellow citizens to save you than in the victory over which you were exulting a little while ago ! Live, though you dared a deed which not even your own father would have pardoned, had he been in the place of L. Papirius ! You shall be reconciled with me when you will”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 35: 6-7).

Then:

-

“When [Papirius] had:

-

✴placed L. Papirius Crassus in charge of the City; and

-

✴forbidden Q. Fabius, the master of the horse, to exercise his magistracy in any way;

-

he returned to the camp [in Samnium]”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 36: 1).

Digression: Crassus as Praefectus Urbi

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 745) argued that Livy’s description of Crassus’ appointment:

-

“... can only mean that [he] was appointed praefectus urbi [Urban Prefect/Prefect of Rome]. This office was not elective: prefects [of this kind] were appointed by the consuls (or a dictator) when all the senior magistrates were absent from Rome.”

Like Stephen Oakley (as above), Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 73) pointed out that the office of praefectus urbi is not attested in the Republic after the mid-5th century BC. He also noted (at p. 72) that:

-

“The primary role of the early praetors was probable the defence of the City.”

Thus, one would have expected Papirius Cursor to rely on the serving praetor for the defence of Rome. However, Brennan observed (at p. 73) that:

-

“Crassus was a relative of the dictator ... [His appointment] as praefectus urbi might be explicable if:

-

✴the consul [Camillus, whom had Papirius replaced in Samnium] was too ill to act [as defender of Rome]; and

-

✴Papirius had taken the praetor into the field as a substitute for the disgraced Fabius, who was debarred ... from further action.

-

[In these circumstances, Papirius might well have] put a man he could trust in charge of the City, and ordered all the regular magistrates [there] not to interfere.”

He acknowledged (at p. 72) that this record of Crassus’ appointment as praefectus urbi might not be genuine, but pointed out that:

-

“... at the very least, [it shows that] such an appointment was conceivable in the later historical period.”

We hear no more about the appointment of a praefectus urbi until 47 BC, when M. Antonius (whom Caesar, as dictator, had appointed as master of horse with responsibility for Rome and Italy while he himself continued the civil war in Spain) appointed his uncle, L. Caesar, to take charge in Rome while he (i.e. Mark Antony) dealt with a mutiny of Caesar’s veterans in Campania.

Digression: M. Valerius as Legate ?

Livy provides a name for the legate who replaced Fabius:

-

“It happened in that year that, every time that Papirius left the army, there was a rising of the enemy in Samnium. But, with the example of Fabius before his eyes, M. Valerius, the lieutenant who commanded in the camp, feared the dread displeasure of Papirius more than any violence of the enemy. And so, when a party of foragers had fallen into an ambush and ... had been slain, it was commonly believed that [Valerius] might have rescued them, had he not quailed at the thought of those harsh orders”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 35: 10-11).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 744) observed that:

-

“Presumably Livy and his sources imagined that this legate to have been either:

-

•M. Valerius Maximus Corvus (consul for the first time in 348 BC); or

-

•his son, M. Valerius Maximus (consul for the first time in 312 BC).

-

But, it is most unlikely that there was authentic evidence for the role of [either] M. Valerius in the events of this year ... .”

Papirius’ Victory

Livy then embarked on an elaborate account of how the dispirited Roman army was defeated by the Samnites, and how Papirius personally directed the treatment of his wounded men and took other measures to restore their morale. With his army re-motivated, Papirus then:

-

“... engaged [again] with the Samnites, ... and routed and dispersed them to such an extent that this was the last time they joined battle with him. His victorious army then ... traversed their territory without encountering any resistance ... Discouraged by these reverses, the Samnites sought peace of Papirius and agreed to give every [man in his army] a garment and a year's pay. Papirius told them to go before the Senate, but they replied that they would wait for him there, committing their cause wholly to his honour and integrity. So the army was withdrawn from Samnium”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 36: 8-12).

Livy then recorded that Papirius returned to Rome in triumph (‘History of Rome’, 8: 37: 1). The fasti Capitolini record that he triumphed over the Samnites as dictator for the first time in the fictitious dictator year of 324 BC. Livy then noted that Papirius:

-

“... would have laid down his office, but was commanded by the Senate first to hold a consular election [see below]”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 37: 1)

In his final remarks on the events of this year were, Livy noted that:

-

“The treaty [with the Samnites] was not completed, owing to a disagreement over terms, and the Samnites left the City with a truce for a year; nor did they scrupulously hold even to that; so encouraged were they to make war, on learning that Papirius had resigned”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 37: 2).

Papirius’ Fictitious Dictator Year

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 695) observed:

-

“There is no good reason to doubt that Papirius Cursor was dictator in this year. ... [This is, for example], presupposed by the legend of his quarrel with Fabius ...”

This is an important point: Papirius’ dictatorship was documented at least a century before the invention of his fictitious dictator year.

Having said that, the inventor of the dictator year would have had to assemble an account of an entire additional year in which Papirius campaigned in Samnium and emerged triumphant, and it is likely that Livy incorporated at least some of this information into his account of the events of 325/4 BC. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998,at p. 696) pointed out that, since the only specific location mentioned in this account is the now-unknown Imbrinium:

-

“... we do not even know whether Papirius and Fabius were fighting in the Liris Valley or in Campania.”

Oakley suggested (at p. 697) that:

-

“Livy’s account [at 8: 36: 1-12] of Papirius’ ultimate victory over the Samnites is told as a pendant to his story of the quarrel [with Fabius], and its details seem to be largely his own or his sources’ invention. It is just possible, that the Samnites did sue for peace and were granted indutae at the end of the year, but the continued fighting [in the following consular year, to which Livy alluded - see below] ... scarcely enhances the credibility of the report.”

However, he argued that:

-

“The basic facts that Papirius ... won a victory and celebrated a triumph need not doubted: they are supported by the fasti Triumphales [above] and also by the fact that [he] must have won a military reputation in order to have been elected as consul in the year after the disaster at the Caudine Forks [see below].”

I am not sure that this is certain proof of Papirius’ triumph:

-

✴the triumph could have been invented by the inventor of the dictator year, whose account pre-dated the fasti Triumphales; and

-

✴as we shall see, it is possible that Papirius secured his election in 320 BC on the basis of his political relationship with Q. Publilius Philo.

In other words, while it seems certain that Papirius campaigned in Samnium as dictator, with Fabius as his master of horse, it is entirely possible that neither of them achieved very much, except for the enduring fame that they achieved by their ‘mortal feud’.

Livy did not explain why the Senate asked Papirius to hold the consular elections before resigning his dictatorship, a task that would normally have fallen to one of the serving consuls:

-

✴It is possible that Camillus had died during his consular year: the only later reference in our surviving sources that might refer to him is in 318 BC, when Livy (‘History of Rome’, 9: 20: 5) recorded that the praetor L. Furius gave laws to the Campani (see below). However, even if he was not killed in 325/4 BC, he might have remained severely incapacitated at the time of the elections.

-

✴There is no particular reason to think that Brutus was detained by the military situation in the Vestini, but we cannot exclude the possibility that he had pressed on into northern Samnium.

In other words:

-

✴it is possible that Livy had a reliable source for the information that Papirius presided over the election of the consuls of 323 BC before resigning his dictatorship; but

-

✴it is also possible that his source here was the inventor of the consul-free dictator year.

Events of 323 and 322 BC

Events of 323 BC

According to Livy, L. Papirius Cursor, the dictator of 325/4 BC:

-

“... would have laid down his office [after his triumph over the Samnites], but was commanded by the Senate first to hold a consular election. He announced that C. Sulpicius Longus had been chosen for the second time, together with Q. [Aulius] Cerretanus”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 37: 1)

See Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 753) for the correct name of this second consul.

Livy recorded that:

-

“ ... the defection of the Samnites [in this year] was followed by a new war with Apulia, [and] armies were sent out in both directions”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 37: 3).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 752) observed, Livy’s sources were at variance with each other, and the detail of these campaigns in now unrecoverable. He concluded that:

-

“Whatever the truth in this matter, Livy’s testimony for this year supports the view that the Romans were involved in Apulia before [their disastrous engagement with the Samnites at the] Caudine Forks [see below].”

Events of 322 BC

According to Livy, in 322 BC:

-

“... when Q. Fabius [Maximus Rullianus] and L. Fulvius [Curvus] were consuls, the dread of a serious war with the Samnites (who were said to have gathered an army of mercenaries from neighbouring tribes) occasioned the appointment of Aulus Cornelius Arvina as dictator and M. Fabius Ambustus as master of the horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 38: 1).

Livy had sources for two variant versions of the campaigning of this year in Apulia and Samnium. According to Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at pp. 757-8), Livy’s preferred version (which he presented in chapters 38-39) involved a campaign fought at an unknown location in Samnium that led to a triumph for the dictator Arvina. However, Livy noted that:

-

“Some writers hold that this war was waged by the consuls, and that it was they who triumphed over the Samnites; they say that Fabius even advanced into Apulia, where he took a great deal of booty. There is no dispute that Aulus Cornelius was dictator in that year: the doubt is whether he was appointed to administer the war, or in order that there might be somebody to give the signal to the chariots at the ludi Romani (since the praetor, L. Plautius, happened to be very sick) and whether, having discharged this office, ... he resigned the dictatorship”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 40: 1).

He noted (in a famously exasperated passage) that:

-

“ ... it is not easy to choose between these accounts ... I think that the records have been vitiated by funeral eulogies and by lying inscriptions under portraits, every family endeavouring mendaciously to appropriate victories and magistracies to itself, a practice that has certainly wrought confusion in the achievements of individuals and in the public memorials of events. Nor is there extant any writer contemporary with that period on whose authority we may safely take our stand”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 40: 3-5).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at pp. 757-8) preferred Livy’s second version, not least because the ‘fasti Triumphales’ recorded triumphs in this year for:

-

✴Fabius, over the Samnites and the Apulini; and

-

✴Fulvius, over the Samnites.

He suggested (at p. 759) that:

-

“... a dictatorship for the holding of games is far more likely to have been changed by a sensationalising annalist into one for [military purposes] that vice versa.”

He also noted (at p. 150) that Fabius Ambustus was the father of the consul, Fabius Maximus,, and that the fighting attributed to him by Livys preferred sources:

-

“... nearly 40 years after his first consulship looks most implausible.”

He observed (at p. 760) that the choice of this variant allows us to discount Livy’s:

-

“... glamorous battle ... as nothing more than annalistic invention and its account of Samnite overtures for peace as nothing more than moralising in preparation for [his account of the Romans’ defeat] at the Caudine Forks [see below].

It might be added that, if this battle did take place, no significant strategic advantage seems to have been gained from the victory. Oakley also observed that the more likely variant:

-

“... provides further evidence for the Romans’ involvement in Apulia in the years before the Caudine Forks ”.

Disaster at the Caudine Forks (321 BC)

Livy began Book 9 by describing 321 BC as the year of:

-

“... the Caudine Peace, the notorious sequel to a disaster to the Roman arms:

-

✴the [unfortunate] consuls were T. Veturius Calvinus and Sp. Postumius [Albinus]; and

-

✴the Samnite’s general for that year was C. Pontius:

-

•his father Herennius far excelled [all the Samnites] in wisdom; while

-

•[C. Pontius himself] was their foremost warrior...”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 1: 1).

Thus Livy set the scene for his account of a Roman humiliation that is still remembered as such to this day.

Fresco (4th century BC) from Tomb 114 of the Andriulo Necropolis near Paestum

Now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Paestum

From the website I Sanniti

This fresco is often taken to portray the Samnite victory at the Caudine Forks (321 BC)

Livy’s account of the encounter under discussion here began with Pontius’ army:

-

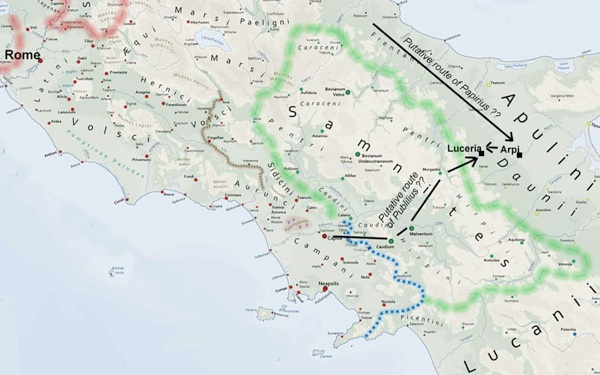

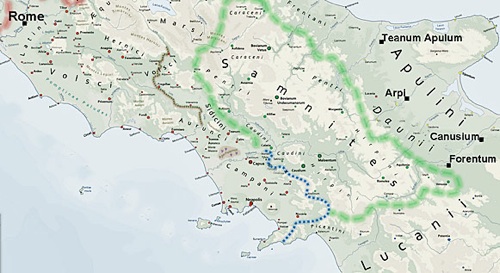

“... camped in the vicinity of Caudium. [From this secret location], he dispatched ten soldiers disguised as shepherd in the direction of Calatia, where he had heard that the Roman consuls were already camped. [The ‘shepherds’] were ordered to graze their flocks at different places near to the Romans and, on encountering [Roman] raiding parties, they were all to say the same thing; that the Samnite levies were in Apulia, where they were laying siege ... to Luceria [in Apulia], which they were on point of taking it by assault. ... The Romans [took the bait and] did not hesitate in deciding to help their good and faithful allies of Luceria, [not least because they wanted] to avoid a general defection Apulia”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 2: 1-5).

This suggests that the Apulini, including those of Luceria, had honoured the agreement that they had reached with the Romans in 226 BC (see above). Thus:

-

“The only question was the route that they should take. There were two roads [from Calatia] to Luceria:

-

✴one skirted the Adriatic and, though open and unobstructed, was as long as it was safe; while

-

✴the other, which led through the Caudine Forks, was shorter, but [much more dangerous, since it passed through] two narrow, deep and wooded defiles ... Having entered the first of these, [the army would have only two options: to retrace its steps [through the first ravine] or to continue through the second, which was even narrower and more difficult than the first”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 2: 5-8).

The Romans decided on the second route and marched into the inevitable ambush: with the Samnites blocking both ravines, all they could do was build a fortified camp in the plain between them. The consuls had no alternative other than to sue for peace. In Livy’s account:

-

“Pontius made answer that, ... since they would not acknowledge their defeat, ... he intended to send them, unarmed and with a single garment each. under the yoke [an arch of spears]”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 4: 3).

The details of Livy’s account of the preceding events have been shown to have been largely invented. In particular, as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 26) observed:

-

“... it seems rather unlikely that, in 321 BC, the Romans would have contemplated marching through the middle of Samnium. It is therefore more likely that [the consuls] were trying to deliver a decisive blow against Samnite communities in the area of Caudium and Beneventum.”

He also pointed to other sources that suggest that the Romans were almost certainly defeated in battle before they sued for peace:

-

✴According to Cicero:

-

“Veturius and Sp. Postumius ... lost the battle at the Caudine Forks, and our legions were sent under the yoke”, (‘De Officiis’, 3:109).

-

✴According to Appian:

-

“... the Romans were defeated by the Samnites and compelled to pass under the yoke”, (‘Samnite Wars’, fragment 6).

Thus, it seems that the army did indeed submit to the humiliation of marching, almost naked, under the yoke.

Livy then recorded a surprisingly generous offer from Pontius: once the Romans accepted this humiliation:

-

“The other peace conditions would be on equal terms: if the Romans would evacuate the Samnite territory and withdraw their colonies, then Romans and Samnites would live thereafter by their own laws on the basis of an equal foedus. He was ready to strike a foedus with the consuls on these terms but, if any of them unacceptable to them, he forbade their envoys to return to him”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 4: 3-5).

However, Livy claimed that these terms were not accepted:

-

“The consuls ... declared that no foedus (treaty) could be made without the authorisation of the Roman people, the presence of fetials and the customary ritual. Consequently, the Caudine Peace was entered into:

-

✴not by means of a foedus, as people in general believe and as [Q. Claudius Quadrigarius] actually states; but

-

✴by a sponsio (solemn pledge) [made by the consuls]”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 5: 1-2).

However, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 31 et seq.) presented arguments in favour of the testimony of Quadrigarius, observing (at p. 31) that:

-

“... the whole notion of sponsio [a pledge given by a defeated Roman commander, which required ratification] is a late fiction.”

Livy seems to have adopted it because:

-

✴his sources invented a subsequent Roman victory in 320 BC that expunged the humiliation of the Caudine Peace (see below); and

-

✴this would have violated a formal treaty.

Oakley argued (at pp. 34-6) that, in fact, a foedus was struck and peace prevailed between the Romans and Samnites, at least in 320 BC, and (at p, 36) that:

-

“There is ... no reason to believe that the Romans either repudiated or broke their foedus with the Samnites in either 321 or 320 BC.”

He also argued at p. 76) that:

-

“The Romans almost certainly lost control of Fregellae [under the terms of this treaty - see below]; it is assumed by many historians that they also lost control of Cales, and the [fact that Livy referred to colonies in the plural] perhaps supports this.”

Caudine Peace (320 - 316 BC)

Events of 320 BC

Election of the Consuls for 320 BC

According to Livy, when Postumius and Veturius, the disgraced consuls of 321 BC, returned to Rome, they:

-

“... shut themselves up in their houses and refused to transact any public business, except that the Senate forced them to name a dictator to preside at the election [of their successors]. They designated Q. Fabius Ambustus [as dictator], with Publius Aelius Paetus as the master of the horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 7: 12-13).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 112) observed:

-

“Livy writes somewhat slackly: it was impossible for both consuls to nominate a dictator and, [furthermore], a dictator appointed his own [master of horse].”

Livy then recorded that:

-

“A flaw in [the appointment of the dictator and the master of horse] occasioned [their] replacement by M. Aemilius Papus, as dictator and L. Valerius Flaccus, as master of the horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 7: 14).

Livy did not explain the nature of the flaw that led to the vitiation of Ambustus’ appointment: Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 113) observed that:

-

“... it is tempting to argue that the [vitiation] ... came about because of [Ambustus’] nomination by consuls whose imperium was regarded as imminutum [diminished] after their military defeat.”

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 113) observed that this double dictatorship is sometimes doubted (and the record in the fasti Capitolini for this year no longer survives). However, Oakley argued that:

-

“... in the aftermath of a major defeat such as that at the Caudine Forks, it is hardly surprising that there was something of a political crisis at Rome.”

As it happens, even the appointment of a second dictator did not resolve the situation: according to Livy, Aemilius was unable to hold the consular elections:

-

“... because the people were dissatisfied with all the magistrates of that year. The state [therefore] reverted to an interregnum. The interreges were: first Q. Fabius Maximus, [who presumably failed to hold elections within the allowed five-day period]; and then M. Valerius Corvus, who announced the election to the consulship of:

-

✴Q. Publilius Philo (for the third time); and

-

✴L. Papirius Cursor (for the second time).

-

[This secured] the unmistakable approval of the citizens, for there were, at that time, no leaders more distinguished”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 7: 14-5).

Interestingly, the protracted and controversial nature of the election process for the consuls of 320 BC is very similar to that for the consuls of 326 BC (discussed above). I argued above that Q. Publilius Philo (consul in 327 BC , prorogued as proconsul in 326 BC) had orchestrated Paprius’ election to his first consulship in 326 BC, and that this marked the start of a close relationship between the two men: they then shared the consulship in both 320 and 315 BC. Their respective elections in the aftermath of the disaster at the Caudine forks is unsurprising:

-

✴Publilius had already triumphed in 339 BC (over the Latins) and in 326 BC (over the Samintes and the Neapolitani); and

-

✴Paprius had already triumphed in 325/4 BC (over the Samnites).

Nevertheless, it seems that they had had to overcome significant political opposition in order to return to the consulship in 320 BC.

Dictators of 320 BC

The fasti Capitolini, list three dictators among the magistrates of 320 BC:

-

✴C. Maenius, with M. Foslius Flaccinator as his master of horse;

-

✴L. Cornelius Lentulus, with L. Papirius Cursor (II) as his master of horse; and

-

✴T. Manlius Imperiosus Torquatus, (III), with L. Papirius Cursor (III) as his master of horse.

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 168) observed:

-

“Nowhere else in our sources for the history of the Roman Republic are three dictatorships recorded for one year, ... [although], in a year of crises [like 320 BC], one should not be unduly surprised by an odd pattern in the fasti.”

None of the surviving sources specify the reason for these dictatorships: as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 167) observed, the fasti would have provided an indication of the respective causae, but this information is no longer legible. To take this further, we need to look at each of the putative dictators in turn.

Dictatorships of C. Maenius

Maenius had triumphed as consul following the Romans’ definitive victory in the Latin War in 338 BC. The fasti Capitolini recorded that he was subsequently appointed as dictator on two occasions:

-

✴320 BC: C. Maenius [record of causa lost], with M. Folius Flaccinator as his master of horse; and

-

✴314 BC: C. Maenius II, rei gerundae causa, with M. Folius Flaccinator II as his master of horse.

Livy was apparently unaware of Maenius’ dictatorship in 320 BC, but he recorded his dictatorship of 314 BC in some detail, and our analysis can conveniently begin by looking at what Livy had found in his sources for that year.

Livy began his account of the putative dictatorship of 314 BC by recording that, after the Samnites had defeated the Romans at Lautulae in 315 BC, many of Rome’s allies began to show signs of defecting and:

-

“... there were even secret conspiracies among the nobles at Capua. When these were reported to the Senate, ... tribunals of enquiry were voted, and it was decided to appoint a dictator quaestionum exercendarum causa (to conduct investigations). C. Maenius was nominated, and he named M. Folius as master of the horse. This development caused great alarm [at Capus], and the ringleaders, Ovius and Novius Calavius, did not wait to be denounced to the dictator ... [before committing suicide]”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 26: 5-7).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at pp. 3oo-1) observed:

-

“There is no reason to doubt that that Maenius held a quaestio (investigation) at Capua [in 314 BC], but Diodorus Siculus must be right to suggest [at ‘‘Library of History’, 19: 76: 3] that he had gone] there as the head of an army and was prepared to fight, [albeit that this proved to be unnecessary].”

Livy then had Maenius return to Rome and, as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 3o4) pointed out:

-

“His account of what actually happened [there] is quite bizarre...”

This account began with assertion that:

-

“... [since] the field of enquiry at Capua [had been exhausted, the proceedings were transferred to Rome: [it was claimed that the Senate had appointed a not dictator] for the investigation of specified individuals in Capua, but ... [for the investigation] of all who had anywhere combined or conspired against the State; and coitiones honorum adipiscendorum causa factas (coalitions that had been formed for the purpose of winning honours) were against the interests of the State”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 26: 8-9).

In other words, Livy claimed that Maneius was appointed as dictator quaestionum exercendarum causa in 314 BC to investigate any and all conspiracies against the State, irrespective of whether these had been hatched in Rome or in any of the allied communities (including Capua).

This leaves us with two mutually exclusive assertions relating to Maenius’ dictatorship of 314 BC:

-

✴the fasti Capitolini recorded and and Diodorus Siculus implied that Maenius was as dictator rei gerundae causa in order to investigate the conspiracy at Capua and to take whatever action (presumably involving his army as required)in order to suppress it; and

-

✴Livy (who did not claim that Maenius had command of an army) recorded that he was appointed as dictator quaestionum exercendarum causa in order to investigate any and all conspiracies against the State (starting with Capua and then Rome, but subsequently extending to the territories of all the Roman allies).

We now need to look at the particular claims that Livy made for Maenius’ putative actions in Rome as dictator quaestionum exercendarum causa in 314 BC:

-

✴He claimed that these investigations were to be very wide-ranging:

-

“The enquiry began to take a wider range, in respect both of charges and of persons, and the dictator was content that there should be no limit to the jurisdiction of his court. Certain nobiles were accordingly impeached, and no-one was allowed to appeal to the tribunes to arrest proceedings”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 26: 9-11).

-

✴At this point, the nobiles allegedly hit back:

-

“When matters had gone thus far, the nobility (and not only those against whom information was being laid, but the order as a whole) protested that the charge did not lie on the patricians, to whom the path to honours always lay open unless it was obstructed by intrigue, but on the novi homines (new men). They even asserted that [Maenius and his] master of horse were more fit to be put upon their trial than to act as inquisitors in cases where this charge was brought, and they would find that out as soon as they had vacated their office [and were, themselves, open to prosecution]”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 26: 11-3).

-

✴However, Maenius and Foslius chose to resign immediately in order to defend themselves, and Maenius, in his resignation speech, asserted that:

-

“The very fact that this office was conferred on me is witness to my innocence; for, it was necessary to select as dictator exercendis quaestionibus (to conduct investigations):

-

•not the most distinguished soldier (as has often been done at other times, when some crisis in the state required it); but

-

•a man who had lived a life far removed from these cabals”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 26: 15).

Finally, Livy described the end of this affair in three sentences:

-

✴“[Maenius and Foslius }were the first to be tried before the consuls (for so the Senate ordered, and, as the evidence given by the nobiles against them completely broke down, they were triumphantly acquitted”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 26: 20).

-

✴“Even Publilius Philo, a man who had repeatedly filled the highest offices as a reward for his services at home and in the field, but who was disliked by the nobiles, was put on his trial and acquitted”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 26: 21).

-

✴“As usual, however, this inquisition was a novelty that it had strength enough to attack illustrious names only when it was a novelty; it soon began to stoop to humbler victims, until it was finally stifled by the very cabals ... that it had been instituted to suppress”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 26: 22).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 304) argued that:

-

“Difficulties and inconsistencies abound [in this part of Livy’s account] ... and, above all, [it] is replete with the motifs and terminology of the late Republic. Modern attempts to explain [it] are extraordinarily diverse in their interpretations.”

He concluded (at p. 306) that:

-

“It is conceivable that a dim memory did survive of an occasion on which Maemius had tried to extend the powers of his dictatorship so as to carry out political business at Rome ..., and this may be the seed from which Livy’s full account grew. ... [However], Diodorus Siculus gives no hint that the dictatorship [of 314 BC] was in any way controversial, and ... it is easier to believe that the annalists invented most of the episode in order to provide a colourful scene in the ‘Struggle of the Orders’. ... [This hypothesis] would explain why scholars have struggled to find a satisfactory explanation of the episode: it is [probably] difficult to interpret because most of the events described by Livy never happened.”

On the other hand, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 168) also pointed out that:

-

“... the very [fact of the] extraordinary nature of the notices in the fasti Capitolini [of three dictatorships in 320 BC] strengthens their credibility. They are rejected by [some scholars, ... but others] are rightly more cautious.”

In other words, it is quite likely that Maenius did indeed serve as dictator in 320 BC, albeit that none of our surviving sources now record the causa for this dictatorship. It is important, in this context, to take account of a later passage by Livy, which comes in a speech of 310 BC that he attributed to the plebeian tribune P. Sempronius Sophus (in which Sempronius allegedly demanded the resignation of the censor Ap. Claudius Caecus):

-

“Recently, within these ten years [i.e., at some time in the period 320 - 310 BC], when the dictator, C. Maenius, quaestiones exerceret (conducted investigations) more rigorously than was safe for certain great men, he was accused by his ill-wishers of being tainted with the very felony that he was investigating and abdicated the dictatorship so that he might face the charge as a private citizen”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 34: 14-5).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p 167, note 1) observed that Attilio Degrassi (in completing the record for 320 BC in the surviving fasti Capitolini) gave the causa of Maenius’ dictatorship in this year as ‘quaest(ionum) exerc(endarum)’, (in order to hold investigations), albeit that Degrassi acknowledged that this was only a guess. To see how good a guess this might have been, we need to consider:

-

✴what might have provoked a formal investigation of coitiones honorum adipiscendorum causa factas (coalitions that had been formed for the purpose of winning honours); and

-

✴why might such an investigation been made in 320 BC.

On the first point, Roberta Stewart (referenced below, at pp. 167-8 and note 84), who accepted 314 BC as the date of Maenius’ investigations as dictator, suggested that the coitiones honorum adipiscendorum causa factas (coalitions that had been formed for the purpose of winning honours) that he investigations had addressed a charge of malpractice in the election of Publilius and Papirius as consuls for that year, despite the fact that they should have been ineligible, since they had:

-

✴already served together in 320 BC; and

-

✴both iterated in 314 BC without waiting for the required period of ten years between consulships.

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 306) rejected this, reasonably pointing out that:

-

“... we have no record of similar iterations of consular pairs causing difficulties”; and

he had earlier pointed out (at p. 39) that, among many other examples of iterating consular pairs:

-

✴T. Veturius Calvinus and Sp. Postumius Albinus (the first consular pair to be elected on two occasions after the passing of the lex Genucia in 342 BC) had served together in both 334 and 321 BC; and

-

✴Q. Fabius Maximus Rullianus and P. Decius Mus had served together in 308, 297 and 295 BC).

However, Oakley’s observations would not rule out the election of Maenius as dictator in order to investigate electoral malpractice in 320 BC, since:

-

✴the election T. Veturius Calvinus and Sp. Postumius Albinus as cos I in 334 BC and cos II in 321 BC (which must have involved electoral ‘co-operation’, if not ooutright malpractice) might have been put forward as one reason for the disaster that had characterised their second consulship;

-

✴as we have seen, the process for electing Publilius and Papirius as consuls of 320 BC had been chaotic, and could easily have given rise to charges of electoral malpractice, particularly if (as argued above) Publilius could have been thought to have ‘engineered’Paprius election to his consulship of 326 BC ; and

-

✴both Publilius and Papirius had already held the consulship in the previous decade:

-

•Publilius was cos II in 327 BC and cos III in 320 BC; and

-

•Paprius was cos I in 326 BC and cos II in 320 BC.

I therefore suggest that we might reasonably:

-

✴accept:

-

•the surviving evidence from the fasti Capitolini that Maenius served as dictator in 320 BC (as well as in 314 BC);

-

•Livy’s evidence at 9: 34: 14-5 that Maenius was appointed as dictator quaestionum exercendarum causa’ at some time in the period 320 - 310 BC;

-

•Attilio Degrassi’s guess that this causa was recorded in the now-lost part of record of Maenius’ dictatorship of 320 BC; and

-

•Roberta Stewart’s suggestion that the coitiones honorum adipiscendorum causa factas that Maenius investigated as dictator had addressed a charge of malpractice in the election of Publilius and Papirius as consuls; but

-

✴assume that these investigations had related to the consular elections of 320 rather than those of 314 BC.

In support of this hypothesis, it should be noted that:

-

✴not a single dictator quaestionum exercendarum causa is recorded in the fasti Capitolini as they survive; and

-

✴Maenius is the only dictator of this type recorded in the surviving passages in Livy’s ‘History of Rome’.

This does not prove that Maenius was the only man ever appointed as dictator quaestionum exercendarum causa during the Roman Republic, but it does indicate that such appointments were extremely rare, and, as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 168) observed (above):

-

“... in a year of crises [like 320 BC], one should not be unduly surprised by an odd pattern in the fasti.”

Dictatorship of L. Cornelius Lentulus

The fasti Capitolini record Cornelius as:

-

✴Publilius’ consular colleague in 327 BC; and

-

✴dictator [causa illegible] in 320 BC, with L. Papirius Cursor (II) as his master of horse

This is the only dictatorship that Livy recorded in 320 BC : he professed himself to be amazed that some sources claimed that the Romans’ victories over the Samnites in 320 BC (discussed below) were:

-

“... won by:

-

✴L. Cornelius [Lentulus], as dictator, with L. Papirius Cursor as master of the horse; rather than

-

✴the consuls [Publilius and Papirius] and, in particular, by Papirius”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 15: 9-10).

We know from a passage of Aulus Gellius that Q. Claudius Quadrigarius, who was writing in the early 1st century BC, probably held the view that Livy had rejectd: in a section in which Gellius investigated the precise meaning of the word indutiae (a truce), he asked rhetorically:

-

“ ... if a truce is to be defined as only lasting for a few days, what are we to say about the fact, recorded by Quadrigarius in the 1st book of his ‘Annals’, that C. Pontius, the Samnite, asked the Roman dictator for a truce of six hours ?” (‘Attic Nights’, 1: 25: 6).

John Briscoe (in T. Cornell, referenced below, 2013, Volume III, p. 308, Fragment 16) observed that:

-

“The fragment [under discussion here] will belong to [Quadrigarius’] account of the alleged Roman victory revenging Caudium in 320 BC ... [His apparent reference to ‘the Roman ‘dictator’] demonstrates that, in his account, the campaign was conducted by the dictator L. Cornelius Lentulus, with L. Papirius Cursor as [his master of horse, as in the alternative sources described by Livy] ...”

Obviously if (as both Stephen Oakley and John Briscoe suggest), the battle of 320 BC is fictitious, then the accounts of it by both Livy and Quadrigarius must be discounted. Furthermore, as Oakley pointed out (above), if this is accepted, then we have no reliable evidence for any fighting between Rome and the Samnites in 320 BC. Even if there were unrecorded Roman military engagements in this year (perhaps, for example, in the Liris valley):

-

✴the consuls Publilius and Papirius would presumably have been experienced enough to deal with them without the need for a dictator; and

-

✴even if the Senate had pressed for the appointment of a dictator for military purposes, it is hard to imagine the circumstances in which Papirius would have agreed to serve as his second-in-command.

For these reasons, I think that we can discount the possibility that Cornelius’ dictatorship was for military purposes. I return to the question of the likely causa for this dictatorship after discussing that of T. Manlius Imperiosus Torquatus.