Roman Italy (1st century BC)

Second Triumvirate (37 - 31 BC)

Roman Italy (1st century BC)

Second Triumvirate (37 - 31 BC)

Octavian’s Second Battle against Sextus

Sextus resumed his blockade of Italy in early 38 BC. However, Menodorus, who held Sardinia for Sextus, defected to Octavian with 60 ships and 3 legions. Octavian asked Antony (who was then in Athens with Octavia) to meet him at Brundisium. Antony duly arrived but left again when (for whatever reason) Octavian failed to make an appearance. He apparently wrote to Octavian urging him to honour the Pact of Misenum.

Octavian nevertheless assembled two fleets for an invasion of Sicily, one under the joint command of Calvisius Sabinus (who had been consul in 39 BC) and Menodorus, which set sail from Etruria and the other under his own command. Before the fleets could meet up, that first was checked and that under Octavian suffered an outright defeat. Soon after, what remained of both of them was destroyed in a storm.

Octavian divorced Scribonia immediately upon the birth of their daughter Julia (probably in October 39 BC) and, after an indecently short period, married the recently-divorced Livia (already the mother of Tiberius and pregnant with Drusus) in January 38 BC.

War with Sextus Pompeius (38-6 BC)

Octavian’s problems did not end with this victory at Perusia: the grievances that had caused the war and those that were caused by the subsequent the reprisals were exacerbated by the actions of Sextus Pompeius (the son of Pompey the Great), who was securely based on Sicily and was able to use his formidable naval capability to disrupt the Italian grain supply.

C. Calvisius Sabinus who was famously one of only two senators who had tried to defend Octavian’s ‘father’, Julius Caesar, when he was murdered in 44 BC, subsequently became an active supporter of Octavian. He served as consul of 39 BC and then as the admiral of Octavian’s fleet. Together with Menodorus, who had defected from Sextus to Octavian in 39 BC, he assembled one of the two fleets with which Octavian intended to invade Sicily in 38 BC. Sabinus and Menodorus duly set sail from Etruria, but were intercepted before they could join up with the second fleet, which was under Octavian’s command and which suffered an outright defeat. Soon after, what remained of both of fleets was destroyed in a storm. When Menodorus subsequently deserted again, this time back to Sextus, Octavian relieved Sabinus of his naval responsibilities and appointed Agrippa in his place.

Octavian was not able to assemble a fleet for a second attempt against Sextus until July 36 BC.

Octavian suffered a serious setback off Mylae in August 36 BC.

He secured a definitive victory off Naulochus in September 36 BC.

Second Triumvirate (37 - 31 BC)

Aureus (RRC 540/1, 36 BC)

Obverse: bearded head of Octavian: inscription: IMP CAESAR DIVI F III·VIR ITER R P C

Reverse: temple of Divus Julius: inscription: DIVO IVL (on temple architrave); COS ITER ET TER DESIG

Meeting of Octavian and Mark Antony at Tarentum (mid 37 BC)

As the first triumvirate (which had been instituted for 5 years on 27th November 43 BC) approached its end, Octavian sent Maecenas (see below) to Mark Antony with a request for another meeting in Italy. Antony and Octavian duly met at Tarentum in the summer of 37 BC and apparently renewed their agreement, apparently on the basis that two matters still required resolution:

✴Octavian had yet to defeat Pompeius; and

✴Mark Antony had yet to defeat the Parthians.

Antony gave Octavian the 120 ships (and their commander, Titus Statilius Taurus) that he had brought from the east and received the promise of troops from Italy for his planned Parthian campaign. The promises made to Sextus in relation to the augurate and designated consulship were formally rescinded.

It is unclear whether or not the renewal of the triumvirate was formalised and backdated to the start of 37 BC:

✴Mark Antony continued to be designated as III·VIR on his coins of this period; while

✴Octavian was designated as III·VIR·ITER on four issues of 37 -6BC (RRC 538/1; RRC 538/2; RRC 540/1 (illustrated above); and RRC 540/2).

Formal reappointment was also implied retrospectively in:

✴the entry for 37 BC in the Augustan fasti Capitolini ((in which, Mark Antony’s name seems to have been removed and subsequently reinstated):

[Triumvirs:] M. Aemilius M.f. [Q.n. Lepidus II], M. Antonius M.f. [M.n. II] , Imp. Caesar Divi f. [C.n. II] ...

Consuls: M. Agrippa L.f. , ...’; and

✴the entry for 36 BC in the Augustan fasti Triumphales, which recorded an ovation on Octavian’s return to Rom after his victory at Naulochus (see below).

Octavian’s Victory over Pompeius at Naulochus (36 BC)

Kathryn Welch (referenced below, 2012, at p. 268) suggested that the agreement that Octavian and Mark Antony in relation to Pompeius might have been part of a plan to:

“... detach as many of Pompeius’ adherents as possible before making an outright attack on him.”

He therefore prepared for another attack, and his prospects improved when Menodorus returned to his allegiance. At about this time, Octavian relieved Calvisius Sabinus of his naval responsibilities and appointed Agrippa in his place. Agrippa (who was recalled from Gaul) spent much of his consular year of 37 BC building a magnificent artificial port (named Port Julius) near Puteoli, in which he assembled a new and powerful fleet for the invasion of Sicily.

Octavian began his invasion of Sicily in July 36 BC, with three fleets:

✴the one that Mark Antony had donated, under Titus Statilius Taurus;

✴another recently built and now commanded by Agrippa; and

✴a third under Lepidus, which had sailed from Africa.

Their first attempt (in August) nearly met with failure: Agrippa secured a naval victory off Mylae but Octavian was defeated and wounded off Tauromenium, at which point he found it expedient to send Maecenas (see below) back to Rome to ensure his position there. However, the decisive naval encounter was a victory for Agrippa off Naulochus (in September), and Pompeius’ position was further undermined when Lepidus managed to land with his army at Lilybaeum. As Kathryn Welch (referenced below, 2012, at p. 279) observed:

“In late 36 BC, Pompeius escaped from the [subsequent] carnage of Sicily and lived for another year.”

However, his chances of ever returning to Rome were over. More importantly, Sicily was now securely in the Octavian’s hands: Lepidus subsequently attempted to assert his own claim on the island, but Octavian entered his camp and faced him down in front of his own army, which duly defected. Octavian then sent him into exile, from which point his claims to the title of triumvir were purely notional.

According to Appian, when Octavian returned to Rome:

“... the Senate voted him unbounded honours, giving him the privilege of accepting all, or such as he chose. ... Of the honours voted to him, he accepted an ovation and annual solemnities on the days of his victories, and the erection of a golden image in the Forum, with the garb he wore when he entered the city, to stand on a column covered with the beaks of captured ships. There the image was placed bearing the inscription:

‘PEACE, LONG DISTURBED, HE RE-ESTABLISHED ON LAND AND SEA’”, (‘Civil Wars’, 5: 130).

The ovation that Octavian received on 13th November 36 BC to mark this victory was recorded in the fasti Triumphales as:

Imp. Caesar Divi f. C. f. II, IIIvir r(ei) p(ublicae) c(onstituendae) II

ovans ex Sicilia idibus Novemb

Imperator Caesar, son of the god [Julius], triumvir for the regulation of the Republic:

an ovation from Sicily, 13th November

David Sear (referenced below, at p. 192) observed that:

“The bearded Octavian makes his final appearance [in these coins]. With the defeat of the last Pompeians [whose army included the last of the erstwhile adherents of Caesar’s assassins, Octavian] reverted to being clean-shaven, a sure sign that [Caesar’s murder] had at last been avenged ...”

Rebellion in Rome and Etruria (36 BC)

According to Cassius Dio, in Octavian’s absence from Rome in 36 BC:

“Other matters in the City and in the rest of Italy were administered by one C. Maecenas, a knight, both then [i.e., in July - November 36 BC] and for a long time afterwards”, (’Roman History’, 49: 16:2).

✴Appian recorded that, when Octavian’s fleet was damaged in the storm early in the campaign:

“In anticipation of more serious misfortune, [Octavian] sent Maecenas to Rome on account of those who were still under the spell of the memory of Pompey the Great, for the fame of that man had not yet lost its influence over them”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 99).

According to A. J. M. Watson (referenced below, at p. 99):

“... it seems that [this] was more of a diplomatic mission than one with a military purpose; ... because the populace in Rome began to riot, Maecenas, Octavian's principal diplomat, was sent to Rome to mollify them.”

✴When Octavian suffered a more serious setback off Tauromenium in August, Appian recorded that:

“He sent Maecenas again to Rome on account of the revolutionists; and some of these, who were stirring up disorder, were punished”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 112).

A. J. M. Watson (referenced below, at p. 99) suggested that:

“The tenure of [Maecenas’] administration [of Rome and Italy] really began in mid-August, with the naval defeat ... off [Tauromenium]. As a result of this [defeat], a rebellion began in Etruria [as recorded by Cassius Dio, above] and Octavian gave Maecenas control of Rome and Italy, [with orders] to keep Rome loyal and to [suppress] the [Etruscan] rebellion ... However, before he could deal with [the latter], there was [another] outburst of unrest in Rome ... [which became] Maecenas' first objective ...”

Our sources indicate two distinct episodes of violence in Etruria at this time:

✴According to Cassius Dio, during Octavian’s absence from Italy in 36 BC:

“... parts of Etruria ... had been in rebellion, [but they] become quiet as soon as word came of his victory [at Naulochus]”, (’Roman History’, 49: 15: 1).

✴According to Appian, even after the victory:

“... Italy and Rome itself were openly infested with bands of robbers, whose doings were more like barefaced plunder than secret theft. Octavian appointed [C. Calvisius] Sabinus to correct this disorder. He [Sabinus] executed many of the captured brigands and, within one year, brought about a condition of absolute security”, (’Civil Wars’, 5:132).

Thus, Emilio Gabba (referenced below, at p. 100) summarised:

“Still in 36 BC, the entire area of Etruria was in revolt, and Octavian had to entrust ... Sabinus with the task of wiping out the armed bands that still roamed across central Italy”, (my translation).

Putting these accounts and interpretations together, we might reasonably assume that the revolt in Etruria broke out in August 36 BC and that Maecenas, who was tied up in Rome, delegated the task of suppressing it, probably to Sabinus (although no surviving source actually identifies him at this point). Sabinus’ task was made much easier by the news of the victory at Naulochus, which brought an end to the famine and simultaneously removed any hope that the rebels might have had of a rival to Octavian in the west. Thereafter, Sabinus turned his attention to the lawlessness that still engulfed the region (which might be a euphemism for a programme of reprisals against the former rebels).

It would be a mistake, in my view, to regard this short revolt in Etruria as an isolated event. Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 208) wrote of the Perusine War that it had:

“... blended with an older feud and took on the colours of an ancient wrong. Political contests at Rome and the civil wars into which they degenerated had been fought at the expense of Italy [for decades]. Denied justice and liberty, Italy rose against Rome for the last time.”

In my view, the revolt in Etruria in 36 BC represented a final postscript to the incipient rebellion in central Italy (and elsewhere on the peninsular) that had occupied much of the century. William Harris (referenced below, at p 313-4) suggested (without giving his sources) that:

“Of the more important towns of Etruria, only Tarquinii, Volsinii and Clusium may have survived the triumvirs and Augustus fairly untroubled.”

However, the imperial estate that seems to have been created to the north of Bolsena (link needed) suggests that the area might have suffered confiscations at the hands of Octavian.

Relations with Mark Antony (35-30 BC)

After his meeting with Octavian at Tarentum in 37 BC, Mark Antony crossed the Adriatic with the pregnant Octavia but, during their subsequent journey to the east, he sent her back to Italy. When he arrived in the east, he resumed his affair with Cleopatra. He also embarked on his invasion of Parthia, a campaign that ended in disaster in 36 BC. His daughter with Octavia (named Antonia) and his son with Cleopatra were both born in this year.

In 35 BC, Octavia travelled to Athens with supplies for Mark Antony: he accepted the supplies but refused to meet Octavia and ordered her return to Rome.

Antony finally broke with Octavian in 34 BC. He celebrated a triumph against the Armenians in Alexandria, formally bestowed territories on Cleopatra and their three children (acknowledging paternity of the twins and naming them Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene) and proclaimed that Caesarion (Cleopatra’s first child) was the legitimate heir of Caesar.

33: Second Triumvirate runs out again; Octavian campaigns in Illyria

32: Octavian reads Antonyʹs will (which again declares Caesarion as Caesarʹs lawful heir) in the Senate. The Senate declares war on Egypt and authorises Octavian (who currently holds no magisterial office) as dux or leader of the war effort.

31: Octavian (now consul for the third time) and Agrippa are victorious over Antony and Cleopatra at Actium.

30: Octavian and his forces take Alexandria; Antony and Cleopatra commit suicide

29: Octavian celebrates a triple triumph at Rome (Illyria, Actium and Alexandria) on three successive days, August 13‐15, and attributes the success to Apollo.

28: Octavian dedicates a temple to Apollo on the Palatine Hill next to his home.

27: Octavian ʺhands the Republic back to the peopleʺ and in return receives the title Augustus and a proconsular province including Spain, Gaul, Syria and Egypt.

Rebellion in Rome and Etruria (36 BC)

According to Cassius Dio, in his absence from Rome in 36 BC:

“Other matters in [Rome] and in the rest of Italy were administered by one Caius Maecenas, a knight, both then [i.e., in July - November 36 BC] and for a long time afterwards”, (’Roman History’, 49: 16:2).

✴Appian recorded that, when Octavian’s fleet was damaged in a storm early in the campaign:

“In anticipation of more serious misfortune, [Octavian] sent Maecenas to Rome on account of those who were still under the spell of the memory of Pompey the Great, for the fame of that man had not yet lost its influence over them”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 99).

According to A. J. M. Watson (referenced below, at p. 99):

“... it seems that [this] was more of a diplomatic mission than one with a military purpose; ... because the populace in Rome began to riot, Maecenas, Octavian's principal diplomat, was sent to Rome to mollify them.”

✴When Octavian suffered a more serious setback off Mylae in August, Appian recorded that:

“He sent Maecenas again to Rome on account of the revolutionists; and some of these, who were stirring up disorder, were punished”, (’Civil Wars’, 5: 112).

A. J. M. Watson (referenced below, at p. 99) suggested that:

“The tenure of [Maecenas’] administration [of Rome and Italy] really began in mid-August, with the naval defeat ... off Mylae. As a result of this [defeat], a rebellion began in Etruria [as recorded by Cassius Dio, above] and Octavian gave Maecenas control of Rome and Italy, [with orders] to keep Rome loyal and to [suppress] the [Etruscan] rebellion ... However, before he could deal with [the latter], there was [another] outburst of unrest in Rome ... [which became] Maecenas' first objective ...”

Putting these accounts and interpretations together, we might reasonably assume that the revolt in Etruria broke out in August 36 BC and that Maecenas, who was tied up in Rome, delegated the task of suppressing it, probably to Sabinus (although no surviving source actually identifies him at this point). Sabinus’ task was made much easier by the news of the victory at Naulochus, which brought an end to the famine and simultaneously removed any hope that the rebels might have had of a rival to Octavian in the west. Thereafter, Sabinus turned his attention to the lawlessness that still engulfed the region (which might be a euphemism for a programme of reprisals against the former rebels).

Our sources indicate two distinct episodes of violence in Etruria at this time:

✴According to Cassius Dio, during Octavian’s absence from Italy in 36 BC:

“... parts of Etruria ... had been in rebellion, [but they] become quiet as soon as word came of his victory [at Naulochus]”, (’Roman History’, 49: 15: 1).

✴According to Appian, even after the victory:

“... Italy and Rome itself were openly infested with bands of robbers, whose doings were more like barefaced plunder than secret theft. Octavian appointed [Caius Calvisius] Sabinus to correct this disorder. He [Sabinus] executed many of the captured brigands and, within one year, brought about a condition of absolute security”, (’Civil Wars’, 5:132).

Thus, Emilio Gabba (referenced below, at p. 100) summarised:

“Still in 36 BC, the entire area of Etruria was in revolt, and Octavian had to entrust ... Sabinus with the task of wiping out the armed bands that still roamed across central Italy”, (my translation).

It would be a mistake, in my view, to regard this short revolt in Etruria as an isolated event. Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 208) wrote of the Perusine War that it had:

“... blended with an older feud and took on the colours of an ancient wrong. Political contests at Rome and the civil wars into which they degenerated had been fought at the expense of Italy [for decades]. Denied justice and liberty, Italy rose against Rome for the last time.”

In my view, the revolt in Etruria in 36 BC represented a final postscript to the incipient rebellion in central Italy (and elsewhere on the peninsular) that had occupied much of the century. William Harris (referenced below, at p 313-4) suggested (without giving his sources) that:

“Of the more important towns of Etruria, only Tarquinii, Volsinii and Clusium may have survived the triumvirs and Augustus fairly untroubled.”

However, the imperial estate that seems to have been created to the north of Bolsena (above) suggests that the area might have suffered confiscations at the hands of Octavian.

After Naulochus (36 BC)

Caius Calvisius Sabinus

Constantine I, recut from a bust of Octavian Octavian C. Calvisius Sabinus

From the “basilica forense” of Volsinii Both from the Roman theatre, Spoleto

Museo Nazionale Etrusco, Viterbo Both in Museo Archeologico, Spoleto

We next hear of Sabinus after Octavian’s victory at Naulochus, when, as we have seen, he was charged with the eradication of banditry in Etruria. I suggested above that Maecenas might well have delegated to him the task of suppressing the revolt in Etruria that had probably broken out in the previous month. Whether or not this was the case, there is circumstantial evidence that he participated in a subsequent programme designed to reconcile the Etruscans with their erstwhile oppressor. This is in the form of bust of Octavian, which was re-cut in ca. 315 AD to represent the Emperor Constantine I (illustrated to the left, above), and which was discovered during excavations of a basilica that stood in the later forum of Volsinii (now the archeological area at Poggio Moscini, Bolsena). According to Annarena Ambrogi and Ida Caruso (referenced below, 2012 and 2013), the original bust of Octavian had been of the so-called Béziers-Spoleto type, which is dated to ca. 40 BC. The Spoletan version of this bust (illustrated above, at the centre), which is among the earliest known representations of Octavian, was found during the excavation of the theatre of Spoleto, near a broadly contemporary bust that almost certainly represents Sabinus (illustrated above, on the right): in addition to his posts under Octavian described above, Sabinus was the patron of Spoleto. Spoleto seems to have supported the rebels during the Perusine War but, as Emilio Gabba (referenced below, at p. 102) pointed out, it escaped serious reprisals thereafter (apart from the transfer of the sanctuary at the source of the Clitumnus to Octavian’s new colony at Hispellum). Gabba suggested that Spoletium had fared so well because of Sabinus’ patronage. It seems likely (at least to me) that Sabinus commissioned both:

✴the Spoletan bust of Octavian, as part of a programme of reconciliation during what seems to have been the rapid and successful pacification of the whole Valle Umbra after the Perusine War; and

✴the Volsinian bust of Octavian, this time as part of a programme (perhaps directed by Maecenas) to consolidate Octavian’s position in Etruria after the revolt there and in the euphoria that followed the victory at Naulochus.

The original location of the bust in Volsinii is a matter for conjecture (particularly since the forum in which it was found was not established as such until the Flavian period):

✴As already noted, the Spoletan prototype was found in the Roman theatre there: the similar bust from Volsinii might also have been in a theatre, assuming that (as discussed below) a permanent theatre existed in the city at this time.

✴Another possibility is that the Volsinian bust was commissioned for the Temple of Nortia at Campo della Fiera. This possibility follows from:

•the information (cited above) from Appian that, after Naulochus:

“Cities joined in placing [Octavian] among their tutelary gods”, (’Civil Wars’, 5:132); and

•a suggestion by Marco Ricci (referenced below, p. 19) in connection with the Augustan revival of the Etruscan Federation:

“It is even possible that initially (as was the case elsewhere), Augustus may have associated himself with an existing cult [presumably the cult to which the revived federation was dedicated]” (my translation).

A slightly later example of this practice might be found at the temple of Fortuna Augusta at Pompeii, the cella of which contained a cult statue of Fortuna (a Roman equivalent of Nortia), and also statues of Augustus and other members of the imperial family in the side niches. Ittai Gradel (referenced below, at pp 103-5) stressed that the addition of the adjective ‘Augusta’ (rather than the genitive ‘Augusti’) to Fortuna’s name associated Augustus with Fortuna without transforming her cult here in any fundamental way: Augustus’ image here was not a cult image but simply an image that was located in Fortuna’s temple in order to demonstrate his association with her cult. Thus, it is possible that Sabinus (perhaps directed by Maecenas) associated Octavian in a similar manner with the cult of Nortia at Campo della Fiera.

As Josiah Osgood (referenced below, at p.300) observed, after Naulochus:

“Everything changed so suddenly. There was now only Mark Antony [in the east] and Octavian. Maybe, as Octavian announced, there would be an end to civil wars.”

He referred here to the following passage from Appian:

“When [the victorious Octavian] arrived at Rome [in November, 36 BC], the Senate voted him unbounded honours ... The next day he made speeches to the Senate and to the people .... He proclaimed peace and goodwill, said that the interviews [relating to the triumviral proscriptions] were ended, remitted the unpaid taxes, and released the farmers of the [tax] revenue and the holders of public leases from what they owed. Of the honours voted to him, he accepted ... [inter alia] a golden image to be erected in the forum ... to stand on a column covered with the beaks of captured ships. There the image was placed, bearing the inscription:

‘PEACE, LONG DISTURBED, HE RE-ESTABLISHED ON LAND AND SEA’

... This seemed to be the end of the civil dissensions. Octavian was now 28 years of age. Cities joined in placing him among their tutelary gods”, (’Civil Wars’, 5:130 -2).

Octavian now seems to have embarked on a carefully planned propaganda programme. Josiah Osgood (referenced below, at pp.323-4) commented on his:

“... new persona after Naulochus, ...[which represented the] most significant of several shifts in [his] public image during the triumvirate. ... Now, he would try to ... [repair his image among] the segment of [Italian] society that [he] had antagonised terribly with land confiscations and dissatisfied still further with the war against Sextus... [He now wanted] to show that there would be an end to chaos, that ... property rights did matter. [Among the measures he took with this in mind, he started] dealing with the gangs of bandits that had seized on civil war as an opportunity to menace the Italian countryside. ... In 36 BC, [he] appointed ... Calvisius Sabinus to crush the outlaws, a task that he [carried out] with notable success ...”

Osgood acknowledged that:

“The record that we have in our sources must surely be an echo of Octavian’s own advertisement of this crackdown on crime.”

In my view, Octavian probably elided the categories of rebels (i.e., political enemies) and criminals. Whether or not this was the case, any reprisals against the former were probably minimal: as Josiah Osgood (referenced below, at p. 324) pointed out:

“This time, ... there was no need for dispossessed landowners [in Italy] to take up arms. To settle the 20,000 time-served men who had been fighting at least since the battle of Mutina [of 43 BC], Octavian .... used public land ... and some plots abandoned in the colonies of 41 BC, ... [while] other veterans were sent [outside Italy], especially to Gaul, a province in his control.”

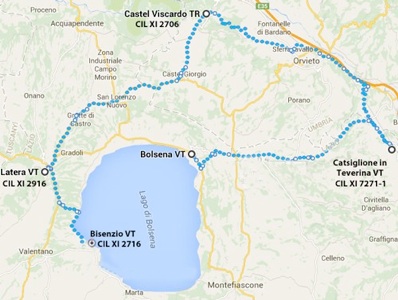

An Imperial Estate near Volsinii ?

Find spots of inscriptions suggesting an imperial estate north of Bolsena

(The routes marked by blue dots are the existing roads between the various marked locations)

Francis Tassaux (referenced below, at pp. 557-60) recorded five inscriptions from the area to the north of Bolsena that might indicate an imperial estate here, at least in the imperial period if not before:

✴Two of these, which date to the reign of the Emperor Augustus (as Octavian became in 27 BC), were found by a farmer in Santa Maria in Paterno, Castiglione in Teverina (some 15 km from Campo della Fiera):

•AE 1904, 0194 commemorated Germanus, a freedman of Augustus and procurator, who had financed the building of a Caesarium and its decoration:

Germanus Aug(usti) / lib(ertus) proc(urator)

Caesareum fec(i)t / et omni cul/tu exornavit

•AE 1904, 0195 commemorated Epaphroditus and Hyacinthus (each of whom was also a freedman of Augustus and procurator) who had restored a shrine dedicated to Apollo Augustus that had apparently fallen into disrepair:

Apollini Aug(usto) Epaphro[ditus Aug(usti) lib(ertus) proc(urator)]

Apollini Aug(usto) Hyacinthus Aug(usti) lib(ertus) p[roc(urator)

aediculam vetustate]/ delapsam(!) sua pecunia [refecit]

The cult site evidenced by the these two inscriptions, which seems to have comprised a Caesarium and a temple of Apollo Augusto, might have been built early in the imperial period: Octavian, who regarded Apollo as his personal patron, dedicated a new temple of Apollo near his palace on the Palatine in 28 BC. The involvement of freedmen of Augustus suggest that this cult site at Castiglione in Teverina was part of an imperial estate and served a private rather than a municipal cult (as noted by Ittai Gradel, referenced below, at p. 83). It is possible that the Caesarium was devoted to Augustus himself (as Gradel assumed), although it is also possible that it was devoted to divus Julius (as suggested, for example, by Stefan Weinstock, referenced below, p. 407, note 4).

✴The other three inscriptions cover a period from the reign of the Emperor Tiberius to that of the Emperor Trajan (i.e., from 14 - 114 AD:

•An inscription (CIL XI 2916) from Latera reads:

Chryseros Ti(berii) Caesaris Drusianus, vil(icus ??)

The possible completion “vilicus” suggests that Chryseros was a slave charged with the management of a villa in this area owned by Tiberius and/or his son, Drusus Julius Caesar (died 23 AD).

•A double-sided inscription (CIL XI 2716) from Visentium (Bisenzio, across the lake from Bolsena), reads:

Neronis Caesaris Aug(usti)

This suggests that the nearby land belonged to the Emperor Nero (54-68 AD).

•The inscription (CIL XI 2706) from Castel Viscardo commemorates a freed slave, Ulpiae Terpsidi, the well-deserving wife of Securus and pious mother of Hilarus. Securus (who was still a slave) held the post of imperial dispensator (treasurer). (referenced below, at p. 558, note 71) suggested that:

“... in all likelihood [Ulpiae] had been a freed woman of the Emperor Trajan [98-117 AD]” (my translation).

As Tassaux observed (at p. 558):

“Certainly, a mere inscription of an imperial slave or freedman is not sufficient to prove the existence of an imperial property. However, the concentration of [these] five testimonies in three specific locations around Bolsena (on the one hand on the shore of Bisentium, on the other hand on the main axis of the [Via] Traiana Nova), which relate to a dispensator, a possible procurator, a possible vilicus and a possible imperial workshop, ... make such a hypothesis likely ” (my translation).

It is, of course, possible that these lands were accumulated over a long period and, indeed, that they never formed a single estate. However, it is tempting to postulate a single imperial estate here that had its origins in land confiscations that might well have occurred here under Octavian in ca. 40-36 BC (see below).

Read more:

D. Briquel, “Il Sacrificio dopo la Guerra di Perugia”, in

G. Bonamenti (Ed.), “Augusta Perusia: Studi Storici e Archeologici sull' Epoca del Bellum Perusinum”, (2012) Perugia, pp. 39-64

J. Warner, “Human Sacrifice at Perusia”, (2012), Sunoikisis Research Symposium

Welch K., “Magnus Pius: Sextus Pompeius and the Transformation of the Roman Republic”, (2012) Swansea

Zs. Várhelyi, “Political Murder and Sacrifice: from Republic to Empire,” in:

J.W. Knust and Zs. Várhelyi (Eds.), “Sacrifice in the Ancient Mediterranean: Images, Acts, Meanings”, (2011) Oxford, 125-41

E. Zuddas and M. Spadoni, “La Lemonia nella Valle Umbra”, in

M. Silvestrini (Ed.), “Le Tribù Romane: Atti della XVIe Rencontre sur l’ Épigraphie (Bari 8-10 ottobre 2009”, (2010) Bari

V. Katz, “The Complete Elegies of Sextus Propertius” (2004) Princeton

L. Keppie, “Colonisation and Veteran Settlement in Italy, 47–14 BC”, (1983) Rome

S. Weinstock, “Divus Julius”, (1971) Oxford

R. Syme, “The Roman Revolution” (1939, latest edition 2002) Oxford

J. S. Reid, “Human Sacrifices at Rome and Other Notes on Roman Religion”, Journal of Roman Studies, 2 (1912) 34‑52

Return to Roman History (1st Century BC)