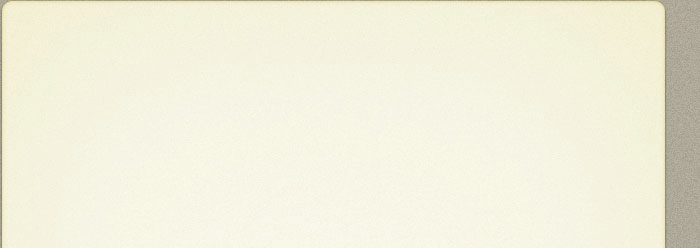

Civil War in Italy (83 - 81 BC)

Civil War in Italy ( 83-2 BC)

Adapted from Gareth Sampson (referenced below, Map 5, at p. 15)

According to Appian, in early 83 BC, when Sulla had completed his arrangements for the continuing governance of the provinces in the east, he sailed:

-

“... from the Piraeus to Patrae with five legions of Italian troops and 6,000 horse, to which he added some other forces from the Peloponnesus and Macedonia, in all about 40,000 men. He then sailed from Patrae to Brundusium in 1600 ships”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 77).

According to Plutarch:

-

“When Sulla [had been] about to transport his soldiers, he had been concerned that, when they had reached Italy, they might disperse to their several cities. [However], they [had taken] an oath of their own accord to stand by him and to do no damage to Italy without his orders ... Sulla, ... after thanking them and rousing their courage, crossed over to confront, as he himself says, 15 hostile commanders with 450 cohorts”, (‘Life of Sulla’, 27: 3).

At the time of Sulla’s arrival, Cn. Papirius Carbo, who had ended the previous year as sole consul, still held imperium as proconsul in Italy and Cisalpine Gaul. The Augustan fasti Capitolini record the serving consul as L. Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus and C. Norbanus, and Appian was clear that these three men shared the task of preventing Sulla’s return to Rome:

-

“C. Norbanus and L. Scipio, who were then the consuls, and with them Carbo, who had been consul the previous year (all of them moved by equal hatred of Sulla and more alarmed than others because they knew that they were more to blame for what had been done), levied the best possible army from the city, joined with it the Italian army, and marched against Sulla in detachments. They had 200 cohorts of 500 men at first, and their forces were considerably augmented afterward”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 82).

Sulla’s First Coinage in Italy

As discussed in the previous page, Sulla was able to rely on L. Licinius Lucullus (who remained in Asia as proquaestor) to collect the huge fines that he (Sulla) had imposed there, and to direct part of this and other ‘booty’ from the east to finance of Sulla’s war in Italy. As a result, Sulla was able to use the mint that travelled with him to convert bullion from the east into coinage in Roman denominations, which was presumably fungible with the ‘legitimate’ coinage that was minted at Rome. His coinage allowed him to pay (and hence to maintain the loyalty of) his soldiers after their return to Italy and, once it was in circulation, to establish his credentials with the Italians. In the sections below, I discuss these early issues and the messages that they might have conveyed to Sulla’s ‘audience’.

RRC 359/1 and RRC 359/2

Aureus issued by Sulla, probably n 84/83 BC, when on his way back from Greece to Italy (RRC 359/1)

Obverse: L. SULLA: Head of Venus, wearing diadem; Cupid holding palm-branch on right

Reverse:IMPER ITERVM: jug and lituus flanked by two trophies

Probably produced at a military mint travelling with Sulla

The issue that Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at pp. 373-4) catalogued as RRC 359 comprises:

Both the gold and the silver coins have the same iconography, in which the issuer is identified as ‘L. SULLA, IMPER ITERVM’, with the honorific indicated that Sulla held the title imperator (commander-in-chief of an army) and had held it on at at least one earlier occasion. I discuss the likely significance of this title in a later section.

The goddess on the obverse is Venus, identified here by the accompanying and unmistakable figure of Cupid. This seems to have been the earliest appearance on the obverse of a Roman coin, as evidenced by this extract from the CRRO database, which lists, in chronological order, all the issues in which she appears before 78 BC (the year of Sulla’s death): the diadem worn by Sulla’s Venus became her defining attribute when her bust subsequently appeared on Roman coins. She had previously appeared on the reverses of:

-

✴issues by two families that are known to have claimed descent from Aeneas and thus of Venus:

-

•the gens Julia (RRC 258/1 and 320/1); and

-

•a minor wing of the gens Memmia (RRC 313/ 2-4 and 349/1 - see the comment on their family claims by Michael Crawford, referenced below, at p. 321); and

-

✴possibly on the reverse of RRC 205/2, which was issued by Sulla’s grandfather (see the comment by Michael Crawford, referenced below, at p. 250).

It is possible that Sulla used her on his obverse because the Cornelii Sullae claimed descent from Venus and Aeneas. However, his claims on her patronage extended beyond any such familial link: we know from Plutarch that:

-

“... when writing to the Greeks on official business, [Sulla] styled himself Epaphroditus (Favourite of Aphrodite/ Venus); and, in [Greece], his name is inscribed on his trophies as: ‘Lucius Cornelius Sulla Epaphroditus, [where the agnomen means ‘favourite of Aphrodite/ Venus’’]”, (‘Life of Sulla’, 34: 2).

As we saw on the previous page, Plutarch refers here to a pair of trophies that Sulla erected at Chaeronea in commemoration of his victory over Mithridates’ army there in 86 BC. These are surely the trophies that were represented on the reverse of the coin. We also know that Sulla referred to himself as his army’s imperator after this battle. In short, these coins proclaimed Sulla as the imperator who was the favourite of Venus, the ancestress of Aeneas and Romulus, through whose never-failing patronage he had defeated Mithridates and driven him out of Asia. The fact that Cupid on the obverse held a palm branch presumably indicated that Sulla had now crossed to Italy to bring peace.

A jug and a lituus (curved staff of the augurs) appear at the centre of the reverse, within the space enclosed by words IMPER and ITER and the two trophies. These are clearly religious objects:

-

✴the lituus (curved augural staff) frequently appeared on coins issued by or in commemoration of members of the college of augurs and (as Stewart pointed out at p. 171) unambiguously referred to augury; but

-

✴(as Stewart pointed out at p. 173) the jug, which often appears in both:

-

•pictorial representations of the act of sacrifice; and

-

•friezes depicting sacrificial implements;

-

usually does so as the container of the liquid (presumably wine) that is about to be used in a ritual libation.

This is the earliest known Roman issues in which this combination appears, as evidenced by this extract from the CRRO database (which lists in chronological order all the entries that include the words jug and lituus), and we might reasonably wonder why Sulla chose to use it at this time. However, we should first consider the significance of the augural lituus in isolation.

The lituus (without the jug) had appeared in four issues by the before RRC 359, as evidenced by this extract from the CRRO database, (which lists, in chronological order, all the issues in which the lituus appears before 78 BC, the year of Sulla’s death). The presence of the lituus in the first three of these issues in easily explained:

-

✴in each of the first two (RRC 241/1 and 243/ 1-5), the lituus refers to the issuer’s cognomen, Augurinus; and

-

✴in the third (RRC 264/1), the lituus (which is behind the head of Roma on the obverse) refers to the augurate of the issuer’s ancestor, M. Servilius Pulex Geminus (see Michael Crawford, referenced below, at p. 289).

That leaves RRC 334/1, which was issued in 97 BC by L. Pomponius Molo, who claimed descent from Numa Pompilius (the legendary second king of Rome): the lituus appears on reverse of his coin in the hand of Numa, as he stands before an altar and prepares to sacrifice a goat. As Victoria Győri (referenced below, at pp. 49-50), in her discussion of this coin, observed that Numa was traditionally believed to have been an augur, as evidenced by the following passage by Livy:

-

“[Numa instructed] the people ... [about] what prodigies ... were to be attended to and expiated. To elicit these signs of the divine will, he dedicated an altar to Jupiter Elicius on the Aventine and consulted the god through auguries about which prodigies were to receive attention”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 20: 7).

The likelihood is that, on Pomponius’ coin, Numa was depicted consulting Jupiter ‘through auguries’.

On the basis of this prior evidence, the most obvious interpretation of the lituus in RRC 359 is that it refers to Sulla’s augurate. The evidence that he belonged to the College of Augurs at some point comes from:

-

✴a passage by Suetonius:

-

“[The grammarian] Cornelius Epicadus was a freedman of L. Cornelius Sulla, the dictator, and [served as] one of his calatores (summoners) in the augural priesthood...”, (‘Lives of Illustrious Men: Grammarians’, 12, translated by John Rolfe, reference below, at p 401); and

-

✴one side of a coin (RRC 434/2) that Sulla’s grandson, Q. Pompeius Rufus issued in 54 BC, where he is designated as ‘COS’ and represented by a lituus and a curule chair.

However, as we saw on the previous page, according to Appian, during Sulla’s failed negotiations with the Senate immediately prior to his return to Italy, he had:

-

“... demanded ... his former dignity, his property, and the priesthood, and that they should restore to him in full measure whatever other honours he had previously held”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 79).

Andrew Drummond (referenced below, at p. 398) argued that:

-

“... the strong probability is that the augural symbols of RRC 359 refer to Sulla's augurate and that [these coins were issued] before or soon after [his] invasion of Italy. The augurate is the only priesthood we know Sulla to have held and it is this priesthood alone that Sulla himself advertises on his coinage ...

He argued that:

-

✴the priesthood of which Sulla had been deprived (according to Appian in the passage quoted above) was his augurate; and

-

✴he now demanded its restoration.

That is, indeed, very likely. However, Drummond conceded (at p. 391) that:

-

“... the basis of the association of the jug with the augurate is not self-evident ...”

It seems to me that, if this is all that Sulla wanted to achieve by the iconography of his coins, well-established and well-understood symbol of the lituus itself would have been sufficient for his purposes. We therefore need to consider:

-

✴the precise significance of his introduction of the jug to the iconography of RRC 359 ; and

-

✴why this combination of the jug and lituus subsequently appeared so frequently on coins issued from this point until (as we shall see) it was used for the last time on denarii issued in 37 BC by the triumviri Mark Antony and Octavius.

Victoria Győri (referenced below, at pp. 49-50) argued that:

-

“From the time of Sulla onwards, however, there was a tendency to symbolise the extension of the augur’s duty to the military sphere and the lituus began to be combined with military iconography.”

In the case of RRC 359/1-2, she cited part of the the following passage Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at pp. 373-4:

-

“The jug an lituus, normally the symbols of the augurate, are ... puzzling [here]. The most probable view, on the basis of literary anf epigraphical evidence, is that Sulla was not an augur in 84-3 BC, ... [albeit that] he was certainly one at some stage. ... On balance, I incline to the view that he became an augur only in 82 BC, dispossessing L. Scipio Asiaticus. As for the jug and lituus on this issue, although they could theoretically allude to the augurate of an ancestor of Sulla, it seems to be more satisfactory to hold that they were regarded by Sulla as symbolising a claim to [legitimate] imperium ...[He] could reasonably attach some [sic] importance to the claim that his declaration as hostis was invalid and that his Lex Curiata, [which would have been passed in the presence of the augurs was] consequently still valid.”

I argue here that the jug and lituus refer to the pontifical and augural jurisdiction over the ritual preliminaries to political action, and particularly to the ceremonies of investiture of Roman magistrates: namely initial auspices; sacrifice; and vows. From the political context of each [of the issues depicting the jug and lituus], I suggest that the symbols allude to ritual in order to legitimise military power.

However, there is no hard evidence for the dates at which Sulla was an augur (and, in particular, it is unclear whether he would have been expelled from the augural college when he was declared a public enemy, had he belonged to it at that time). Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at p. 374) discussed the possibilities and concluded that:

-

“”.

If this is correct, and if, for the reason above, the coins were issued before that date, then the jug and lituus motif must have had a more general religious significance.

Roberta Stewart (referenced below, at pp. 178-9) pointed out that RRC 359 is the first of 14 Republican coins on which the jug/lituus combination combination appears, and argued that:

-

“ The particular political context for the issue of each [of them] suggests the political function of the symbols: in each instance, the legitimate authority of the commander/moneyer was open to question.”

She concluded (at p. 186) that:

-

“On the coins of Sulla and Metellus Pius [see below] in the 80s BC, ... the jug and lituus countered the pronouncements of a politically hostile government in power at Rome. ... [These] symbols of the augury and sacrificial rituals invoked the traditional religious sanctions of political power [in Rome] and represented the commander's right to command, most immediately to command his army.”

If I have understood her correctly, she argued that issuers like Sulla, whose right to command his armies was denied by the State, nevertheless remained in command on the basis of divine approval (as witnessed by his success in war).

RRC 367

Aureus issued on Sulla’s behalf by L. Manlius Torquatus, probably soon after Sulla’s return to Italy (RRC 367/2)

Obverse: L·MANLI T PROQ: Helmeted head of Roma

Reverse: L·SVLLA·IM[P]: Triumphator, crowned by flying Victory, in quadriga

Probably produced at a military mint travelling with Sulla

Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at pp. 386-7) established that the issue that he catalogued as RRC 367/1-5 (see this extract from the CRRO database):

-

“... forms by far the largest part of the Sullan coinage.”

Although it comprises:

-

✴two forms of the aurei (types 2 and 4); and

-

✴three forms of the denarii (types 1, 3 and 5);

the iconography is essentially consistent across the issue. The reverse inscription identifies the issuer as L. Manlus Torquatus, proquaestor, and he was presumably the ‘Torquatus’ who, according to Plutarch (‘Life of Sulla’, 29:4) was present with Sulla at the Colline Gate in 82 BC (see below). Since Sulla is still identified only as imperator on these coins, they (like RRC 359 above) must have been issued before 82 BC.

The reverse cannot represent Sulla’s triumph, which (as we shall see) he celebrated as dictator in 81 BC. Lucia Carbone and Liv Yarrow (referenced below, at p. 313) argued that:

-

“... the triumphator on the reverse of the coins of RRC 367 leads in the same direction as the trophies on the reverse of RRC 359, namely the depiction of Sulla as an imperator beloved by the Gods, who succeeded in iberating the Roman east from one of Rome’s archenemies.”

They also pointed out (at p. 314) that, in this case, triumphator holds the caduceus, a herald’s staff that was generally a symbol of peace, concord, and reconciliation (like Cupid’s palm branch on RRC 359).

Sulla’s First Coinage in Italy: Analysis and Conclusions

Lucia Carbone and Liv Yarrow (referenced below, at p. 313 and note 67) argued that:

-

“... hoard evidence suggests a date very close in time for the two issues RRC 359 and 367, which could even be contemporary.”

They also argued (at p. 312 and note 63) that, despite the ‘Greek’ connotations of RRC 359,

-

“... the very scant presence of Roman currencies in Greece and in Asia Minor before the 40s BC makes it very difficult to ... [believe that] the RRC 359 issues were produced in Greece or in Asia Minor.”

Since, as noted above, Torquatus, who issued RRC 367 on behalf of Sulla, was in Italy with Sulla at least by 82 BC. Carbone and Yarrow (referenced below, at p. 314) agreed with Piere Assenmaker (referenced below, at pp. 261-3):

-

“... that these coinages were struck [either]:

-

✴at the time of the end of Sulla’s sojourn in the east (and then sent to Italy with the army), or, more probably

-

✴ in Italy, right after Sulla’s army landed in Italy, as the presence of the coins in Southern Italian hoards leads one to think.”

Thus the likelihood is that the propraetor Torquatus was in charge of the mint that had travelled with Sulla to Italy and that RC 359 and 367 were first produced by this mint there in 83-2 BC.

Although Carbone and Yarrow did not attempt to estimate the volume of gold coins issued at this time, they concluded (at p. 316) that:

-

“... the [silver] denarii of the RRC 359 and 367 issues, [which were] the issues financing Sulla’s reconquest of Italy, were ... roughly one half of the issues of the Roman mint in the year 82 BC, ... [which] was a year of extraordinary production.”

They commented (at p. 327) that their estimate of the production size of RRC 359/2 and 367/1, 3 and 5 was far greater than previously estimated. Their conclusion (at p. 326) as to the provenance of the bullion for these issues was as follows:

-

“While only metallurgical analyses will (hopefully) allow us to settle the question in a definitive way, the quantitative analyses pursued in ... this paper made the eastern provenance of the [silver] used for RRC 359/2 and RRC 367/1, 3 and 5 very likely. In sum, [Michael Crawford, referenced below, 2000, at p. 124] was right when he suggested that RRC 359/2 (and possibly RRC 367/1, 3 and 5):

-

‘were made with metal from the Greek world, presumably in large measure melted down booty’”.

Their final, overall conclusions (at pp. 327-8) were as follows:

-

“... a comparison between these Sullan issues and the contemporary coinages produced at Athens and in the province of Asia. ... suggested that Sullan Roman Republican issues and the ‘Sullan’ coinages issued in Athens and in the province of Asia between 85 and 81 BC were of similar size. Integrated with the available literary sources, the production data deriving from different mints allowed us to see historical production beyond a single mint and begin to understand better the scale of the striking necessary to fund Sulla’s march on Rome.”

This is probably only the second instance of the use of the honorific ‘imperator’ on a Roman coin: as I discussed on the previous page, the renegade commander C. Flavius Fimbria, who had killed the legitimate proconsul of Asia, taken command of his two legions and expelled Mitridates from Pergamum (before Sulla captured and executed him), is represented as ‘FIMBRIA IMERAT on three coins discovered there.

-

✴I argued on the previous page that Fimbria’s honorific must indicate that the men under his command at Pergamum had hailed him as imperator after his victory there in 85 BC. If so, then ‘IMPER ITERVM’ on RRC 359 1/2 would indicate that Sulla’s army had hailed him as imperator on two occasions

-

✴As I pointed out on the previous page, the evidence of our surviving sources indicates that Sulla’s army had hailed him at as imperator after his victory at Chaeronea in 86 BC. However, the date of the other (presumably earlier) acclamation is unknown, although a number of scholars (including, for example, Michael Crawford, referenced below, 1974, at p. 374) suggest that this took place in Cilicia in the 90s BC.

-

I think that Fimbria and Sulla each employed the honorific imperator, the title that he had been given by his army, because he had no other legitimate title at his disposal. If this is correct, then :

-

✴Sullas’ putative assertion that his army had given him this honorific twice would smack of one-upmanship; and, more importantly,

-

✴RRC 359 must have been minted before 82 BC, when he became dictator.

In construction from this point

This brings us to the fact that the issue RRC 359/1 comprised coins made from Greek gold. As this extract from the database CRRO demonstrates, this aurei that Sulla issued on his arrival were the first Roman coins to be produced from gold since those issued in 196 BC in honour of T. Quinctius (RRC 548/1). Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at p. 544) argued that this much earlier issue:

-

“... appears to have been struck in Greece. ... If the ‘T. Quinctius’ of the reverse is T. Quinctius Flamininus], the conqueror of Philip V [of Macedonia (and there is no other serious candidate), then the obverse type will be his portrait ..., [a Roman usage that is] otherwise unknown before [Julius Caesar in 44 BC]. Given the extravagant honours paid to Flamininus by the Greeks, it seems to me most likely that the issue was struck [by Greeks] in honour of Flamininus, not by Flamininus [himself].”

In other words, Sulla’s issue of RRC 359/1 in Italy would have been quite extraordinary, particular since (as we shall see) L. Manlus Torquatus produced another issue of aurei of Sulla’s behalf. Meanwhile, Sulla’s soldiers were presumably exchanging the denarii RRC 359/2 with Italian civilians as they marched on to Campania as if they were what we would call ‘legal tender’.

Cn. Pompeius

Shortly after Sulla’s arrival in Italy, the young Pompey assembled three legions from among his father's veterans and led this private army towards Sulla’s camp. According to Plutarch (see below), during this march, he found himself surrounded by armies led by three different commanders:

-

✴two who were to go on to serve as praetor in the following year:

-

•C. Carinas; and

-

•L. Junius Brutus Damasippus; and

-

✴the otherwise unknown Cloelius.

He seems to have evaded them and then engaged with a squadron of cavalry sent by Carbo himself, as he (Carbo) returned to Rome, via Picenum, from his province in Cisalpine Gaul (see below).] Having thus established his credentials and enhanced the size of his army, he marched on towards Sulla’s camp, and:

-

“... when Sulla saw him advancing with an admirable army of young and vigorous soldiers, elated and in high spirits because of their successes, he dismounted his horse and, after being saluted, as was his due, with the title of imperator, he saluted Pompey in return as imperator. [This was remarkable, since] no-one could have expected that a young man, and one who was not yet a senator, would receive this title from Sulla”, (‘Life of Pompey’, 8).

Marcus Licinius Crassus

It seems that Sulla had left his most senior commanders in the east, and that the most senior of the men who accompanied him to Italy was the young Marcus Licinius Crassus.

According to Plutarch, in 87 BC:

“When Cinna and Marius got the upper hand ... [in Rome, Crassus’ father and brother had been among] those who were caught and slain ... Crassus himself, being very young, [had] escaped the immediate peril ... and fled with exceeding speed into Spain, where he had been before,)while his father was praetor there [in 97-3 BC]) and had made friends”, (‘Life of Crassus’, 4: 1).

T. Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 502) observed that Spain had apparently been without a ‘legitimate’ Roman governor for a decade after the return of the elder Crassus to Rome, and that Roman outlaws of both persuasions had therefore taken refuge there in this period. We do not know when the younger Crassus arrived but, when he heard of Cinna’s death in 84 BC, he emerged from hiding and:

“... many flocked to his standard, out of whom he selected 2,500 men, and ... [plundered] Malaca ... as many writers testify, but they say that he himself denied the charge ... After this, he ... crossed into Africa and joined Metellus Pius (see below), an illustrious man, who had raised a considerable army. However, he remained there for only a short time: after dissension with Metellus, he left [for the east] and joined Sulla, with whom he stood in a position of special honour”, (‘Life of Crassus’, 6: 1-2).

Sulla’s Commanders in Italy

Since Sulla had left his most senior commander, L. Licinius Murena, in the east, his most important commanders in Italy joined him after his arrival from Greece:

-

✴Q. Caecilius Metellus Pius; and

-

✴Cn. Pompeius (the future Pompey the Great).

Q. Caecilius Metellus Pius

Denarius issued by Q. Caecilius Metellus Pius after Sulla’s return to Italy (RRC 374/2)

Obverse: Head of Pietas; stork (symbol of piety towards parents)to the right right

Reverse:IMPER: jug and lituus inside a laurel wreath

Probably produced at a military mint travelling with Sulla

Metellus had served as praetor in 89-8 BC and, as we have seen, had acted as a negotiator between Octavius and Cinna in 87 BC. According to Appian, as Sulla began his advance from Brundisium towards Rome in 83 BC:

-

“He was met on the road by ... Metellus, who had been chosen [as proconsul] some time before to finish the Social War, but had not returned to the city for fear of Cinna and Marius. He had been awaiting the turn of events in [Africa], and now offered himself [to Sulla] as a volunteer ally with the force under his command, as he was still a proconsul (for those who have been assigned to this office may retain it until they return to Rome)”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 80: 1).

Metellus’ decision to take refuge in Africa after 87 BC is easily understood: his father, Q. Caecilius Metellus Numidicus, had held the African command against Jugurtha in 109-7 BC, until his enemy Marius had effectively robbed him of his command. (The elder Metellus had then gone into exile, and ‘our’ Metellus had earned the epithet ‘Pius’ because of his efforts to secure his recall, which had taken place in 99 BC). Thus he would have had many potential supporters there. Furthermore, it seems that the province was outside the control of the ‘legitimate’ government: in 88 BC, when Marius had fled from Sulla, the governor of Africa, P. Sextilius, had denied him asylum there, and we know of no later ‘legitimate’ governors until C. Fabius Hadrianus (mentioned above) landed in in 84 BC. Thus, as T. Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 543) observed, Metellus (who probably retained the imperium from his Italian command) seems to have had total control over Africa for much of the period before the arrival of Hadrianus:

-

✴According to Plutarch (‘Life of Crassus’, 6: 1-2), in 84 BC, Metellus was still in Africa, where he had raised a considerable army.

-

✴According to the surviving summary of the now-lost Book 84 of Livy’s ‘History of Rome’:

-

“After ... Metellus... , who had embraced the politics of [Sulla] and provoked a war in Africa, had been defeated by the praetor C. Fabius [Hadrianus], the faction of Carbo and the adherents of Marius passed a senatorial decree that all armies everywhere ought to be disbanded”, (‘Periochae’, 84:5).

Sensibly, Sulla appointed him as second-in-command and, as we shall see, he was consequently declared a public enemy shortly thereafter.

A denarius (RRC 374/2, illustrated above), which Metellus issued from a mint in northern Italy, celebrated his agnomen ‘Pius’ on the obverse and designated him as imperator on the reverse. Michael Crawford (referenced below, 1974, at p. 390) observed that some scholars attribute the jug and lituus on the reverse to:

-

“... an unattested augurate [of Metellus. ... However,], the type seems clearly derived from the reverse type of RRC 395/1-2 ...”

As we shall see, Sulla issued these earlier coins at the time of his arrival in Italy, when Metellus still claimed that he retained his proconsular imperium despite his ejection from Africa and the decree that made him a public enemy. Roberta Stewart (referenced below, at p. 180) argued that, in the case of both RRC 359/1-2 and RRC 374/2, the‘jug and lituus’ motif:

-

“... sanctioned the propriety of [the issuer’s] command.”

Liv Yarrow (referenced below, at p. 273) observed that Metellus presents himself as Sulla’s equal:

-

“... engaged in a common endeavour [but] not his subordinate.”

Sulla’s Battles for Rome (83-2 BC)

The new consuls, Norbanus and Scipio, marched from Rome into Campania, in order to stop Sulla’s march on Rome. Juan Strisino (referenced below, at pp. 33-4) summarised the subsequent events as follows:

-

“Sulla ... arrived at Campania in the summer of [83 BC, and partially defeated ... Norbanus ... near Canusium.. ... follwong which, Norbanus withdrew with the remnants of his army to Capua. In the meantime, Scipio, commanding second consular army with Sertorius at his side, was advancing on Teanum Sidicium ... Sulla, who was heading for Rome, found himself sandwiched between the consular armies and and [therefore] retreated to Cales ... Somewhere between Teanum and Cales, Sulla and Scipio agreed to talk, much against Sertorius' advice. ... What followed with some certainty is that some form of agreement was reached and Sertorius was sent to inform Norbanus about [it]. Instead, [Sertorius] marched to Suessa in July ... and captured the town, thus [causing] the rapprochement to break down.”

Cicero threw some further light on this attempted rapprochement in a speech that he delivered in the Senate in 43 BC:

-

“Sulla and Scipio met between Cales and Teanum [in July 83 BC], one with the flower of the nobility at his side and the other with his wartime allies, to discuss terms and conditions relating to the authority of the Senate, the votes of the people, and the right of citizenship, [should Sulla be allowed to return to Rome]. It is true that faith was not kept at that conference, but there was no [immediate] violence or danger”, (‘Philippics’, 12: 27, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, 2010, referenced below, at p. 215)

When news about Sertorius’ action, Scipio’s army defected to Sulla, who then allowed Scipio to return to Rome (possibly believing that he would still put his terms to the Senate). However, Appian recorded that:

-

“When Sulla, was unable to induce Scipio to change, he sent him away with his son unharmed. He also sent other envoys to Norbanus at Capua to open negotiations ... As nobody came forward, ... Sulla again advanced, devastating all hostile territory, while Norbanus did the same thing on other roads. Carbo hastened to the city and caused Metellus, and all the other senators who had joined Sulla, to be decreed public enemies”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 86).

In the event, both consuls managed to return to Rome, and the war continued. Sertorius proceeded via Etruria to to his praetorian province of Spain (see below). Carbo also returned to Rome from his province of Cisalpine Gaul [possibly via Picenum, where he might have been checked by the young Pompey - see above.] Carbo now declared Metellus and all the senators who had defected to Sulla to be enemies of the State. To add to the sense of doom that must have descended on the City, a disastrous fire of the Capitol destroyed the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus: Plutarch (‘Life of Sulla’, 27) dated the fire to 6th July. Scipio and Norbanus then presided over election of the consuls for the following year:

-

✴Carbo (for his third consulship); and

-

✴C. Marius the Younger (the son of the great C. Marius and, at 26, the youngest consul ever elected).

At the start of the next campaigning season, Sulla sent Metellus and Pompey to Picenum. According to Appian:

-

“At the beginning of spring, there was a severe engagement on the banks of the river Aesis ... between Metellus and [C.] Carinas, Carbo's lieutenant. Carinas was put to flight after heavy loss, whereupon all the country thereabout seceded from the consuls to Metellus. Carbo ... besieged [Metellus, somewhere in Picenum] until he heard that Marius, the other consul, had been defeated in a great battle near Praeneste [see below], at which point he led his forces back to Ariminum, with Pompey ... [in close pursuit]”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 87).

After a digression to report on the Sulla’s parallel activity in Latium (see below), Appian recorded that:

-

“About the same time Metellus gained a victory over another army of Carbo and here, again, five cohorts ... deserted to Metellus during the battle. Pompey overcame [C. Marcius Censorinus] near [Sena Gallica] and plundered the town”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 88).

It seems likely that Carbo’s second battle was located between Ariminum and Sena Gallica. Following these engagements::

-

✴Carbo moved to Clusium in Etruria (see below);

-

✴Pompey followed Carinas as he fled southwards into Umbria and:

-

“In the plain of Spoletium, Pompey and Crassus ... killed some 3,000 of Carbo's men and besieged Carinas, the opposing general”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 90).

-

This cannot be completely accurate: Carinas surely found refuge in the hilltop city of Spoletium itself. He managed to escape in the night and continued south, in order to go to the aid of the beleaguered Marius at Praeneste (see below). Crassus also captured Tuder (in Umbria) at about this time.

-

✴Metellus sailed north:

-

“... toward Ravenna, and took possession of the level wheat-growing country of Uritanus [now unknown]”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 89).

Appian began his parallel account of the events in Latium with Sulla’s capture of Setia, after which, he defeated Marius at a now-unknown location called Sacriportus:

-

“This was the beginning of a terrible disaster for Marius. His shattered army fled to Praeneste with Sulla in hot pursuit. The Praenestines gave shelter to those who arrived first but the gates were closed as Sulla approached the city, and Marius had to be hauled over the walls by ropes. There was another great slaughter round the walls ..., [in which] Sulla captured a large number of prisoners and killed all the Samnites among them ...”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 87).

Sulla then erected siege works around Praeneste, hoping to starve Marius out of the city. According to Appian:

-

“When Marius saw that his condition was hopeless, he hastened to put his private enemies out of the way. He wrote to Brutus [probably L. Junius Brutus Damasippus], the city praetor, to call the Senate together on some pretext or other and to kill [four of them]:

-

✴P. Antistius [Pompey’s father-in-law];

-

✴the other Papirius [C. Papirius Carbo Arvina - see Robert Broughton, referenced below, at p.26, note 8);

-

✴L. Domitius [Ahenobarbus]; and

-

✴[Q.] Mucius Scaevola, the pontifex maximus ....

-

Their bodies were thrown into the Tiber ...”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 88).

Meanwhile, having established that Rome was undefended, Sulla established his camp on the Campus Martius and stayed there long enough to:

-

✴arrange for the confiscation of the property of those of his enemies, who had fled; and

-

✴reassure ‘the people’ at a public assembly.

Thereafter:

-

“Having arranged such matters as were pressing and put some of his own men in charge of the city, [Sulla] set out for Clusium, where the war was still raging”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 89).

As we shall see, Sulla’s hold on Rome was not yet secure.

It seems from Appian’s account that Carbo had now established a base of operations at the Etruscan city of Clusium, and that Sulla left Rome in order to confront him there. En route, he defeated:

-

✴a detachment of Celtiberian cavalry that had been sent to Carbo by ‘the praetors in Spain’ (which might be a confused reference of Q. Sertorius, mentioned above), in an engagement on the banks of the river Glanis;

-

✴another enemy detachment, in an engagement near Saturnia;

after which:

-

“A severe battle was fought near Clusium between Sulla himself and Carbo, lasting all day. Neither party had the advantage by the time that darkness put an end to the conflict”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 89).

In the same passage, Appian recorded that another Sullan army attacked Neapolis (presumably because it was in some sort of alliance with the Samnites), killed most of its inhabitants and stole its fleet of warships.

Carrinas joined Carbo in Etruria, where he was confronted by Sulla. After what seems to have been an inconclusive engagement near Clusium, Sulla was forced to return to Praeneste, where an army of Samnites and Lucanians was attempting to release Marius. The rebels lifted the siege and marched on the undefended Rome, but Sulla caught up with them outside the Colline gate (in the northern stretch of the walls of Rome). His definitive victory there:

-

✴put an end to what had, in effect, been a post-script to the Social War; and

-

✴extinguished the hopes of Sulla’s opponents in Rome.

Praeneste soon fell to Sulla’s army, now commanded by Q. Lucretius Afella, and Marius committed suicide: according to Appian, when his corpse was discovered:

-

“Lucretius cut off his head and sent it to Sulla, who exposed it in the forum in front of the rostra”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 94).

Carbo fled to Africa and then to Sicily (see below).

Sulla’s Dictatorship (82 - 79 BC)

Proscriptions

The first thing we hear about Sulla after he became master of Rome in November 82 BC is that he summoned the remnants of the Senate to meet at the Temple of Bellona in the Campus Martius, outside the pomerium: according to Plutarch, as he began to address the Senate:

-

“... those assigned to the task in the [nearby Circus Maximus] began to cut to pieces the 6,000 [prisoners that he had taken at the Colline Gate]. he shrieks of such a multitude, who were being massacred in a narrow space, filled the air, of course, and the senators were dumbfounded; but Sulla, with the calm and unmoved countenance with which he had begun to speak, ordered them to listen to his words and not concern themselves with what was going on outside, for it was only that some criminals were being admonished, by his orders. This gave even the dullest Roman to understand that, in the matter of tyranny, there had been an exchange [of tyrants rather than] a deliverance”, (‘Life of Sulla’, 30: 3-4).

As Catherine Steel (referenced below, at p. 662) observed:

-

“It had only been a matter of weeks since ... M. Iunius Brutus Damasippus [see above] had ordered a massacre at a meeting of the Senate that he had convened; now Sulla was demonstrating what would happen to his enemies. This initial act of terror was followed over the next six months by the organised terror of the proscriptions.”

Alexander Thein (referenced below) described this programme as follows:

-

“Proscription was a system of state-sponsored political violence invented by Sulla [at this time] . The names of [his] enemies were published on lists set up in the forum at Rome, and their properties were confiscated and sold at public auction. Anyone whose name appeared on the list was an outlaw who could be killed with impunity. An official reward of two talents or 12,000 denarii was promised to anyone who killed one of the proscribed. There were also rewards for informers who betrayed the hiding places of the proscribed ... , while anyone who saved the lives of proscribed fugitives or offered them assistance of any kind was threatened with harsh penalties up to and including [their own] proscription. Sulla posted three lists with a total of 520 names in the first instance ... [According to Appian(‘Civil Wars’, 1: 95)] the total figure was in excess of 40 senators and 1,600 knights. The original meaning of the Latin word ‘proscriptio’ was ‘publication’, often the advertisement of items for sale at auction. After Sulla, it also acquired the meaning of ‘death list’. For Sulla, the logic of proscription was to cement his power by rewarding his friends and exacting vengeance on his enemies. The proscribed were all men of wealth and status from the elites of Rome and small-town Italy and, in theory, they were all guilty of civil war opposition to Sulla, but many were added to the lists because they had incurred the private enmity or greed of Sulla’ s adherents. Confiscated estates were auctioned for far less than their true value, and Sulla ensured that his followers received the most attractive bargains. The proscribed were hunted down and killed by freelance assassins or soldiers motivated by the promise of the bounty, and some were killed or betrayed by members of their own family or household.”

According to Appian:

-

“When everything had been accomplished against [Sulla’s] enemies as he desired, and there was no longer any hostile force except that of Sertorius, who was far distant[see below], Sulla sent Metellus into Spain against him and seized upon everything in the city to suit himself. There was no longer any occasion for laws, or elections, or for casting lots, because everybody was shivering with fear and in hiding, or silent. Everything that Sulla had done as consul, or as proconsul, [presumably including the proscriptions], was confirmed and ratified, and his gilded equestrian statue was erected in front of the rostra with the inscription:

-

‘Cornelius Sulla, the ever Fortunate’;

-

for so his flatterers named him on account of his unbroken success against his enemies. And this flattering title still attaches to him.”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 97).

Sulla’s Appointment as Dictator

CIL I2 0723 (2): L(ucio) Cornelio L(uci) [f(ilio)]/ Sullai Felic[i]/ dic(tatori)

From Clusium (Chiusi), now reused in the Piazza del Duomo there

Adapted from Bill Thayer’s webpage on the Loeb translation of Plutarch’s ‘Life of Sulla’

Frederik Vervaet (referenced below, at pp. 37-8) described the unprecedented events that led up the appointment of a Roman dictator in 82 BC after an interval of some 120 years:

-

“During the years 88-82 BC, [in the aftermath of] the exhausting Social War, Rome itself was, for the first time in its history, thrice shattered by the horrors of full-scale civil war.”

As Appian recorded, this terrible chain of events culminated when:

-

“... Sulla became king, or tyrant, de facto, unelected and holding power by force and violence. However, since he needed the pretence of being elected, this was ... managed in the following way. ... [In normal circumstances], retiring consuls always presided over the election of their successors in office, and if there chanced to be no consul at such a time, an interrex was appointed for the purpose of holding the consular comitia. Sulla took advantage of this custom: since here were no consuls at this time (Carbo having lost his life in Sicily and Marius in Praeneste), Sulla went out of the City for a time and ordered the Senate to choose an interrex. They chose [L.] Valerius Flaccus, expecting that he would soon hold the consular comitia”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 98).

It seems that Flaccus initially thought that he had been appointed to hold consular elections. However, he was disabused when he received a letter from Sulla:

-

“... ordering Flaccus to represent to the people his own strong opinion that it was to the immediate interest of the city to revive the dictatorship ... He told them not to appoint the dictator for a fixed period, but until such time as he should firmly re-establish the city and Italy and the government generally, shattered as it was by factions and wars. [Sulla] made it clear that] this proposal referred to himself, ... declaring openly at the conclusion of the letter that, in his judgment, he could be most serviceable to the City in that capacity”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 98).

In short, Flaccus, as interrex, was ordered to arrange for Sulla to be appointed as dictator in the comitia centuriata.

Cicero criticised this unconventional procedure on at least two occasions, in terms that indicate that it did much more than enable Sulla’s appointment as dictator:

-

✴In a speech in the Senate on 1st January 63 BC, he condemned the fact that it had given Sulla legal immunity from prosecution:

-

“I think that the most iniquitous of all the laws ... is the one that L. Flaccus, the interrex, passed in regard to Sulla, [which provided] that all his acts, whatever they were, should be ratified. For, while in all other states, when tyrants are set up, all laws are annulled and abolished, in this case, by his law, Flaccus established a tyrant in a Republic”, (‘On Agrarian Law’, 3: 2: 5 , translated by John Freese, referenced below, at p. 489).

-

✴In a work on the ideal legislative system that might well have remained unfinished when he was killed in 43 BC, he wrote that:

-

“In my opinion, the law that a Roman interrex proposed, to the effect that a dictator might, with impunity, put to death any citizen he wished, even without a trial, should be considered unjust”, (‘On the Laws’, 1: 42, translated by Clinton Keyes, referenced below, at p 343).

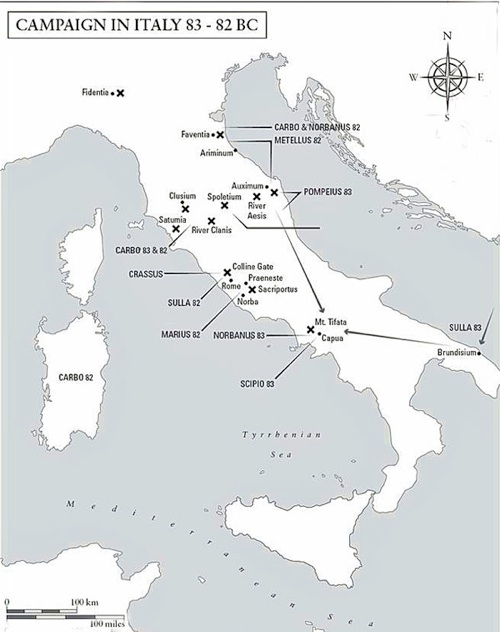

As we have seen, L. Valerius Flaccus (cos 100 BC) was the princeps senatus and he had tried to mediate between Sulla and the consuls in 85 BC. Catherine Steel (referenced below, at p. 660) noted that he was one of only four ex-consuls (apart from Sulla) who were still alive at this time: the other three were:

-

✴his cousin, C. Valerius Flaccus, cos 93 BC, who (as we shall see) was still in his province of Further Gaul;

-

✴M. Perperna, cos 92 BC, the Marian governor of Sicily, who was still in his province (see below); and

-

✴L. Marcius Philippus, cos 91 BC, who captured Sardinia for Sulla in 82 BC and executed its Marian governor, Q. Antonius Balbus.

In other words, it is hard to see who else Sulla could have chosen for his purposes. Cicero threw light on the process used for Sulla’s appointment in a letter that he wrote to Atticus on 25th March 49 BC, when it seemed that Caesar’s appointment as dictator was imminent:

-

“... Sulla [arranged] ... to be nominated [as dictator in 82 BC] by an interrex [whom he then chose as his] master of horse. [In the light of this precedent], why [should] Caesar [not behave in a similarly illegal way]?”, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 183, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at Vol. III, pp. 85-7).

The entry in the Augustan fasti Capitolini for 82 BC can be translated and completed as follows:

-

[Consuls]: C. Marius C.f. C.n. - killed in office ; Cn. [Papirius Cn.f. C.n. Carbo III - killed in office];

-

[Dictator]: L. Cornelius L.f. P.n. Sulla Felix; [master of horse]: L. Valerius L.f. L.n. Flaccus;

-

[legibus scribundis et rei publicae constituendae (in order to write laws and to reconstitute the State)]

Mark Wilson (referenced below, 2021, at p. 290) argued that that Flaccus probably oversaw, not the election of a dictator, but rather the passage of a law in the comitia centuriata naming Sulla as dictator, and that this was probably followed by his investment with imperium. Appian implied that the Senate had been tricked when the interrex presided over the appointment of a dictator rather than the election of suffect consuls, but this is unlikely to have been the case: as Mark Wilson (referenced below, 2021, at pp. 292) pointed out:

-

“Consular elections might have been even more of a farce than [reviving the dictatorship for the first time in 120 years] ... No-one would have been put up for the consulship who was unacceptable to Sulla. ... [His] top lieutenants were hunting down Marian renegades in Spain, Sicily and elsewhere, and the most prominent and capable members of the Senate and nobility had been slaughtered in the recent mutual proscriptions.”

It is possible that Cicero (who entered public life during Sulla’s dictatorship) regarded the appointment of a dictator by an interrex as illegal. This is suggested by the forebodings he expressed in a letter he wrote to Atticus on 25th March 49 BC, when Caesar (who had driven the serving consuls from Italy) was about to enter Rome:

-

✴he thought that Caesar would probably:

-

“... [‘encourage a serving] praetor either to hold consular elections or to nominate a dictator, neither of which is legal, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 183, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at vol. 3, pp. 85-7); and

-

✴resignedly pointed out that:

-

“... if Sulla could arrange ... to be nominated [as dictator in 82 BC] by an interrex [whom he then chose as his] master of horse, why not Caesar?”, (‘Letters to Atticus’, 183, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, 1999, at vol. 3, p. 87).

However, while Cicero clearly (and reasonably) considered that Sulla’s action had been highly unusual and that it might well encourage Caesar to take adopt an even more unusual procedure, he did not claim that it had been illegal; indeed, he would have been well aware of the

It seems that Sulla served as dictator, along with a pair of annually-elected consuls, until 78 BC: for example, Appian recorded that:

-

✴in 81 BC:

-

“... by way of keeping up the form of the Republic, [Sulla] allowed [the people] to appoint consuls. M. [Decula] and [Cn.] Cornelius Dolabella were chosen. But Sulla, like a reigning sovereign, was dictator over the consuls”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 100).

-

✴in 80 BC:

-

“... Sulla, although he was dictator, undertook the consulship a second time, with [Q. Caecilius] Metellus Pius for his colleague, in order to preserve the pretence and form of democratic government”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 103).

-

✴in 79 BC:

-

“... in order to pay court to Sulla, the people chose him consul again, but he refused the office and nominated P. Servilius [Vatia] Isauricus and [Ap.] Claudius Pulcher, and [thereafter] voluntarily laid down the supreme power, although nobody forced him to. It seems wonderful to me that Sulla should have been the first ... tyrant to abdicate such vast power without compulsion, bequeathing it not to sons ... but to the very people he had tyrannised”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 103).

Plutarch also noted that, for reasons that he found hard to comprehend:

-

“... [Sulla] laid down his office of dictator [when he had finished the task for which he had been appointed] and put the consular elections in the hands of the people”, (‘Life of Sulla’, 34: 3).

Suetonius recorded that Caesar, as dictator, became:

-

“... arrogant [in]his public utterances: [for example, as] Titus Ampius records, [he asserted that] the State was nothing, a mere name without body or form, and that Sulla did not know his alphabet [i.e. he did not know what he was doing] when he laid down his dictatorship ... (‘Life of Julius Caesar’, 77)

Appian recorded that Sulla’s letter to Flaccus had included the instruction that the appointed dictator should serve:

-

“... not for a fixed period, but for [however long it took him] to firmly re-establish the City and Italy and the government generally, shattered as it was by factions and wars”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 98).

He elaborated on this in the following paragraph:

-

“The Romans did not appreciate [Sulla’s instructions], but ... [they resigned themselves to the fact that they had no option but to accept] this pretence of an election ... and chose Sulla as their absolute master for as long a time as he pleased. There had been autocratic rule of the dictators before, but it had been limited to short periods. However, under Sulla, for first time, the dictatorship became unlimited and so [a vehicle for] absolute tyranny. All the same, they added, for propriety's sake, that they had chosen him dictator for the enactment of such laws as he himself might deem best and for the regulation of the commonwealth”, (‘Civil Wars’, 1: 99).

Thus, it seems that Appian believed that Sulla’s appointment as dictator was uncongenial to the Roman people primarily because it was not time-limited.

However, Plutarch believed that the Romans resented the revival of a magistracy that he not been used for generations:

-

“... not only [Sulla’s] massacres [of his enemies, but also] the rest of his proceedings ... gave offence. [For example], he proclaimed himself dictator, reviving this particular office after a lapse of 120 years”, (‘Life of Sulla’, 33: 1).

The last dictator recorded in our surviving sources who was appointed for a purpose other than the holding of elections was M. Iunius Pera, in the aftermath of the Romans disastrous defeat at Cannae in 216 BC (see Mark Wilson, referenced below, 2017, at p. 553, entry 77).

Distribution of Roman Provinces between Sulla and the Senate in 83-2 BC

Adapted from Gareth Sampson (referenced below, Map 6, at p. 15)

My addition in Italics: C. Valerius Flaccus, who governed Further/Nearer Spain and Gaul, was apparently unaligned

Second Mithridatic War (83 - 81 BC)

On his departure from Asia, Sulla had left behind his legate, L. Licinius Murena, in command of the legions that he had taken from Fimbria. According to Robert Broughton (referenced below, at p. 64) he:

-

“... invaded Pontic territory in both 83 and 82 BC, in violation of Sulla’s agreement with Mithrdates, but was repulsed in 82 BC with serious losses, [and Sulla] ordered him (perhaps in 81 BC) to cease hostilities,”

Cicero criticised at least three of the laws passed under Sulla’s dictatorship:

-

✴in a speech of 80 BC, when Sulla was still dictator, he criticised the way in which a law that had been meant to deal with land that was confiscated during the proscriptions had actually been applied in the case of the land that had belonged to Sextus Roscius of Ameria

-

“My question is this: how, by virtue of the law dealing with proscription (the Valerian or [Sullan] law, for I ...do not know which it is) ... could the property of Sextus Roscius have been sold? For it is said that it runs as follows:

-

‘that the property of those who have been either proscribed ... or killed in enemy lines should be sold’.

-

[Sextus Roscius had not been proscribed and], as long as there were any lines, he was within those of Sulla: ... he was killed at Rome, during a time of perfect peace, after we had finished fighting”, (‘Pro Roscio Amerino’, 125 , translated by John Freese, referenced below, at p. 235).

Read more:

Wilson M., “Dictator: The Evolution of the Roman Dictatorship”, (2021) Ann Arbor, Michigan

Yarrow L., “The Roman Republic to 49 BC: Using Coins as Sources”, (2021) Cambridge

Carbone L. and Yarrow L., “The Aftermath of The First Mithridatic War And Sulla's Dictatorship: Some Preliminary Historical Analyses Using The 'Roman Republican Die Project’”, Revue Belge de Numismatique et de Sigillographie, 166 (2020) 285-333

Assenmaker P., “La Frappe Monétaire Syllanienne dans le Péloponnèse Durant la Première Guerre Mithridatique: Retour sur les Monnaies ‘Luculliennes”, in:

Apostolou E. and Doyen C., “Coins in the Peloponnese: Mints, Iconography, Circulation, History.: From Antiquity to Modern Times: Volume 1: Ancient Times”, (2018) Athens, at pp. 411-24

Thein A. “Proscriptions”, in:

Bagnall R. et al. (editors), “The Encyclopedia of Ancient History”, (2018) online

Zoumbaki S., “Sulla, the Army, the Officers and the Poleis of Greece: A Reassessment of Warlordism in the First Phase of the Mithridatic Wars”, in:

Ñaco del Hoyo T. and López Sánchez F. (editors), “War, Warlords, and Interstate Relations in the Ancient Mediterranean”, (2018) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 351-79

Wilson M., "The Needed Man: Evolution, Abandonment and Resurrection of the Roman Dictatorship", (2017) thesis of City University of New York

Győri V., “The Lituus and Augustan Provincial Coinage”, Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 55: 1-4 (2015) 45-60

Steel C., “Rethinking Sulla: the Case of the Roman Senate”, Classical Quarterly, New Series, 64, 2 (2014) 657-68

Sampson G., “The Collapse of Rome: Marius, Sulla and the First Civil War (91-70 BC)”, (2013) Barnsley

Shackleton Bailey D. R. (translator), “Cicero: Philippics , 1-6 (Vol. I) and Books 7-14 (Vol. II)”, (2010) Cambridge, MA

Vervaet F. J., “The Lex Valeria and Sulla’s Empowerment as Dictator (82-79 BC)”, Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz, 15 (2004) 37-84

Strisino J., “Sulla and Scipio: 'Not to be Trusted' ? The Reasons why Sertorius Captured Suessa Aurunca”, Latomus, 61:1 (2002) 33-40

Brennan T. C., “The Praetorship in the Roman Republic: Volume 1: Origins to 122 BC”, (2000) Oxford

Crawford M., “The Sullan and Caesarian Periods”, in:

Hollstein W. (editor), “Metallanalytische Untersuchungen an Münzen der Römischen Republik”, (2000) Berlin, at pp. 124-9

Shackleton Bailey D. R. (translator), “Cicero: Letters to Atticus, Volumes I- IV”, (1999) Cambridge MA

Stewart R., “The Jug and Lituus on Roman Republican Coin Types: Ritual Symbols and Political Power”, Phoenix, 51:2 (1997) 170-189

Kallet-Marx R., “Hegemony to Empire: The Development of the Roman Imperium in the East from 148 to 62 BC”, (1996) Berkeley, Los Angeles and Oxford

Crawford M., “Roman Republican Coinage”, (1974) Cambridge

Broughton T. R. S., “The Magistrates of the Roman Republic,Volume II (99 - 31 BC)”, (1952) New York

Freese J. H. (translator), “Cicero: Pro Quinctio; Pro Roscio Amerino; Pro Roscio Comoedo; On the Agrarian Law”, (1930) Cambridge MA

Keyes C. W. (translator), “Cicero:On the Republic; On the Laws”, (1928) Cambridge MA

Rolfe J. C. (translator), “Suetonius: Vol. II”, (1914) Cambridge MA

Return to Roman History (1st Century BC)