Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Third Samnite War (298- 90 BC)

Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Third Samnite War (298- 90 BC)

Prior Events

Gallic Invasion (299 BC)

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

According to Livy, early in 299 BC:

“The Etruscans planned to go to war [with Rome] ... in violation of the truce; but, while they were busy with this project, an enormous army of Gauls invaded their borders ... Putting their trust in money (of which they had great store), they endeavoured to convert the Gauls from enemies into friends, so that, uniting the Gallic army with their own, they might fight the Romans. The barbarians made no objection to an alliance: it was only a question of price. When this had been agreed upon and received, the Etruscans, having completed the rest of their preparations for the war [with Rome], invited their new allies to follow them. However, the Gauls demurred, [arguing that] they had not bargained for a war with Rome ... Nevertheless, they offered to take to the field ..., but on one condition: that the Etruscans allocate to them a part of their land so that they might settle at last in a permanent home. Many of the concilia populorum Etruria (councils of the peoples of Etruria) were held to consider this offer, but nothing could be agreed, not so much because of their reluctance to see their territory reduced, but rather because they were reluctant to have ... so savage a race for neighbours. So, the Gauls were dismissed and departed with a vast sum of money, acquired without any toil or risk. The Romans, who were alarmed by the rumour of a Gallic rising in addition to a war with the Etruscans, lost no time in concluding a treaty with the people of Picenum (‘History of Rome’, 10: 10: 6-12).

Stephen Oakley (2007, at p. 309 conjectured that the Gallic Senones, who had a border with Picenum and who were explicitly mentioned in the context of the Battle of Sentinum in 295 BC, might have been behind this Gallic invasion of Etruria.

Livy noted that T. Manlius Torquatus, who was the consul responsible for Etruria at this time, had fallen off his horse there and died. The Etruscans, having presumably having paid off the Gauls, took Manlius’ accident:

“... as an omen of the war, plucked up courage and declared that the gods had begun hostilities in their behalf. ... The Senate commanded [M. Valerius Corvus Calenus, as suffect consul] to proceed forthwith to the legions in Etruria. His arrival so damped the ardour of the Etruscans that none ventured outside their fortifications ... Nor could [Valerius] entice them into giving battle by ravaging their lands and firing their buildings”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 11: 1-6).

It was at this point that the Romans received news of trouble in Samnium, and:

“... the Senate's anxiety was diverted, in great measure, from Etruria to the Samnites”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 11: 7).

Polybius gave a parallel account that had the Etruscans playing only a minor role in Gallic raid on Roman territory. According to this account, in 299 BC:

“... when a fresh movement [to cross the Alps] began among the Transalpine Gauls, [the tribes of Cisalpine Gaul], who feared that they would soon have a big [inter-Gallic] war on their hands:

✴diverted the migrating tribes from their own territory by bribery and by pleading their kinship;

✴ incited them to attack the Romans instead; and

✴even joined them in this expedition.

They advanced through Etruria, where the Etruscans also joined them, and, after collecting a quantity of booty, they retired quite safely from Roman territory. But, on reaching home, they fell out with each other about the division of the spoil and succeeded in destroying the greater part of their own forces and of the booty itself. (This is quite a common event among the Gauls, when they have appropriated their neighbour's property, chiefly owing to their inordinate drinking and excess)”, (‘Histories’, 2: 19: 1-4).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 152) conceded that these accounts are not mutually exclusive:

“Livy’s version looks very much as if it has been garbled by later annalists and it is perhaps preferable to reject it outright. [In this case], the Etruscans ... helped [the Gauls] to plan a raid on [Roman territory]. This [putative] joint joint expedition [might thus have been] the precursor of the great combined anti Roman armies of 296-5 BC [discussed on the following page].

Treaty with the Picentes (299 BC)

According to Livy:

“The report of a Gallic tumult [in 299 BC], in addition to a war in Etruria, had caused serious apprehensions at Rome; and, with the less hesitation on that account, the Romans concluded an alliance with the state of the Picentes”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 10: 12).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 152) observed that:

“Since the Picentes bordered on the territory of the Gallic Senones, [this] notice of a Romano-Picentine alliance forged in a year in which the Gauls were stirring is particularly credible.”

Declaration of War (298 BC)

According to Livy, in 298 BC, the Romans received information from their new allies that:

“... the Samnites were looking to arms and a renewal of hostilities, and had solicited their help. The Picentes were thanked, and the Senate's anxiety was largely diverted from Etruria [and the Gauls] to the Samnites”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 11: 7-9).

Soon after:

“... envoys from Lucania [a town on the border of Samnium and Campania] came to the new consuls to complain that the Samnites, since they had been unable by offering inducements to entice them into an armed alliance, had invaded their territories with a hostile army and by warring on them were obliging them to go to war. They admitted that the people of Lucania had, on a former occasion, strayed all too far from the path of duty, but they insisted that they were now so resolute as to deem it better to endure and suffer anything than ever again to offend the Romans They besought the Senate to take the Lucani under their protection and to defend them from the violence and oppression of the Samnites. Though their having [already] gone to war with the Samnites was necessarily a pledge of loyalty to the Romans, yet they were none the less ready to give hostages”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 11: 11-13).

After a short discussion:

“The Lucani received a friendly answer, and the league was formed. Fetials were then sent to command the Samnites to leave the country belonging to Rome's allies and to withdraw their army from the territory of Lucania. They were met on the way by messengers, whom the Samnites had dispatched [with instructions] to warn them that, if they went before any Samnite council, they would not depart unscathed. When these things were known at Rome, the Senate advised and the people voted a declaration of war against the Samnites”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 12: 2-3).

First Phase of the War (298 - 295 BC)

Fighting in Etruria (298 BC)

The sources for 298 BC are particularly difficult: there was some Roman engagement in Etruria in that year, which Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 175) characterised as:

“... rather desultory fighting, which had been the norm [in Etruria] since the outbreak of hostilities in [the dictator year] 302/1 BC.”

Fighting in Samnium (297 BC)

Both of the consuls of 297 BC (Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus and Publius Decius Mus) fought in Samnium.

Etruscan/ Samnite Alliance (296 BC)

Livy signalled the start of a more significant phase of the conquest of Etruria in 296 BC, when Decius, who remained as proconsul in Samnium:

“... continued his ravages of Samnite territory until he had driven their army ... outside their frontiers. They made for Etruria, ... where they insisted upon a meeting of principum Etruriae concilium (leaders of the Etruscan council) being convened. ... The Samnite army had come to them completely provided with arms and a war chest, and were ready to follow them at once, even if they led them to an attack on Rome itself”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 16: 2-8).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 200) asserted that the notion that Decius had driven the Samnite army out of its own territory was absurd. Instead, he suggested that a Samnite army under Gellius Egnatius (see below) had:

“... marched north [of its own volition] to help foster the incipient coalition in Etruria and Umbria, and the Romans were either taken by surprise or powerless to stop [it].”

Hostilities in Samnium

According to Livy, the Samnites’ arguments led to:

“... a very serious war against Rome ... being organised in Etruria, in which many nations were to take part. The chief organiser was Gellius Egnatius, a Samnite. Almost all the Etruscan cities had decided on war, the contagion had infected the nearest Umbrian peoples, and the Gauls were being solicited to help as mercenaries. All these [forces] were concentrating at the Samnite camp [at an unknown location in Etruria]”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 18: 1-3).

By this time, L. Volumnius Flamma Violens, one of the the newly-elected consuls, had already left Rome for Samnium so his colleague, Appius Claudius Caecus led an army into Etruria. According to Livy he was initially unsuccessful, and Volumnius;

“Leaving the ravaging of the enemy's fields to [the proconsul] Decius he proceeded with his whole force to Etruria”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 18: 8).

Although (according to Livy) Appius resented Volomnius’ uninvited presence, he eventually yielded and battle commenced.

“Volumnius began to engage before Appius ... and by some accidental interchange of their usual opponents, the Etruscans fought against Volumnius and the Samnites ... against Appius. We are told that Appius, during the heat of the fight, raising his hands toward Heaven ... prayed thus:

‘Bellona, if you grant us the victory this day, I vow to you a temple.’

... after this vow, as if inspirited by the goddess, he displayed a degree of courage equal to that of his colleague and of the troops. ... [Appius and Volumnius] therefore routed and put to flight the enemy ... [and] drove them into their camp. There, by the interposition of Gellius and his Sabellian cohorts (cohortiumque Sabellarum), the fight was renewed for a little time. But ... the camp was now stormed by the conquerors; and whilst Volumnius ... led his troops against one of the gates, Appius, frequently invoking Bellona Victrix, inflamed the courage of his men, who broke in through the rampart and trenches. The [Samnite] camp was taken and plundered, and an abundance of spoil was ... given up to the soldiers. Of the enemy, 7,800 were slain and 2,120 taken [prisoner]”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 19: 16-22).

Ovid recorded that, on 3rd June:

“... Bellona is said to have been consecrated in the Tuscan war, and ever she comes gracious to Latium. Her founder was Appius”, (‘Fasti’, 6).

Livy does not say where this engagement took place. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 211) remarked that this account of it is:

“... notable for the large quantity of annalistic and Livian elaboration to be found in it.”

The so-called ‘Elogium’ of Appius, Elogium’ (CIL VI 40943), which was inscribed with Appius’ statue in the Forum of Augustus (dedicated in 2BC), almost certainly recorded that Appius defeated a force of Etruscans and Sabines and that he built the temple that he had vowed to Bellona: only fragments of it survive, but it can be completed from a copy (CIL XI 1827) that was erected in Arezzo (now in Florence):

“Appius Claudius Caecus, son of Caius, censor, consul twice, dictator, interrex three times, praetor twice, curule aedile twice, quaestor, military tribune three times: has taken many fortresses of the Samnites; has defeated the army of the Sabines and Etruscans; has prevented the concluding of peace with the king Pyrrhus; has paved the Appian way and has conducted water to the city during his censorship; has built the temple of Bellona”

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 2o1) observed that Appius’:

“... vow to Bellona guarantees the report in our sources that he fought a major engagement against the Etruscans, Samnites and Sabines; and the need to make the vow suggests that this battle was hard-fought and desperately close. If, as Livy states, the Romans were victorious, then their victory did no more than stall the build-up of enemy power.”

Hostilities in Campania

The theatre of war now moved to Campania, where the Samnites were devastating the territory of Roman allies, and Volumnius was sent to deal with the situation. According to Livy:

“... it so happened that, just at this time, grave news was received from Etruria. After the withdrawal of Volumnius' army, the whole country, acting in concert with the Samnite captain-general, Gellius Egnatius, had risen in arms; whilst the Umbrians were being called on to join the movement, and the Gauls were being approached with offers of lavish pay. The Senate, thoroughly alarmed at these tidings, ordered all legal and other business to be suspended, and men of all ages and of every class to be enrolled for service ... Arrangements were made for the defence of the City, and the Praetor [Publius Sempronius Sophus] took supreme command”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 21: 1-4).

Fortunately, the crisis was partially relieved when the Senate received:

“... a letter from .. Volumnius informing them that the [Samnite] army that had ravaged Campania had been defeated and dispersed; whereupon, they decreed a public thanksgiving for this success, in the name of the consul. The courts were opened, after having been shut for 18 days, and the thanksgiving was performed with much joy”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 21: 5-6).

Minturnae and Sinuessa

Livy noted that, when the news of victory in Campania had been duly celebrated:

“The next question was the protection of the district that had been devastated by the Samnites. It was decided to settle bodies of colonists about the Vescinian and Falernian country.

✴One was to be at the mouth of the Liris, now called the colony of Minturnae.

✴The other was to be in the Vescinian forest, where it is contiguous with the territory of Falernum. Here, the Greek city of Sinope is said to have stood and, from this, the Romans gave the place the name of Sinuessa.

It was arranged that the tribunes of the plebs should get a plebiscite passed requiring Pub;ius Sempronius, the praetor, to appoint commissioners for the founding of colonies in those spots. But it was not easy to find people to be sent to what was practically a permanent outpost in a dangerously hostile country: [potential colonists preferred to have] fields allotted to them for cultivation”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 21: 7-10).

Velleius Patroculus recorded that:

“... in the 5th consulship of Quintus Fabius, and the 4th of Decius Mus [295 BC], the year in which King Pyrrhus [of Epirus] began his reign, colonists were sent to Minturnae and Sinuessa”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 14: 6).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 233) observed tha:

“... his evidence can be reconciled with [that of Livy] if one argues that the foundations were approved in 296 BC but established only in 295 BC.”

These new colonies on the Tyrrhenian coast were maritime citizen colony, as evidenced by the fact that they were among seven such colonies that (according to Livy, ‘History of Rome’, 27: 38: 4) pleaded their exemption from prolonged military duties elsewhere in 207 BC.

Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 57) noted that both Minturnae and Sinuessa were located on land that the Romans had taken from the Aurunci in 314 BC. (They had already established two Latin colonies, Suessa Aurunca and Interamna Lirensis, on this confiscated land in 313-2 BC). As mentioned on the previous page, the two new citizen colonies were assigned to the Terentia tribe, which had been established in 299 BC, presumably for viritane settlers on the confiscated land. Graham Mason (referenced below, at p. 82) suggested that:

“The main reason for founding both Mintunae and Sinuessa [in 296 BC] was to secure ... the neighbouring fertile lands from the ravages of the Samnites, who had repeatedly overrun the area. Livy ... says as much. ... [The apparent reluctance of prospective colonists] implies no negative attitude toward the two sites as such ... It reflects the circumstances of that point in the Third Samnite War; there was another attempted Samnite incursion into the area the following year ”

However, with the end of the war in 290 BC, the barriers to citizen settlement would have disappeared. Furthermore, it is possible that a more extensive programme for settling this fertile plain, now protected by the new colonies, came to fruition.

Situation in Etruria

On the other hand, the situation in Etruria continued to deteriorate:

“The attention of the Senate was diverted ... to the growing seriousness of the outlook in Etruria. There were frequent despatches from Appius warning them not to neglect the movement that was going on in that part of the world; four nations were in arms together (the Etruscans, the Samnites, the Umbrians, and the Gauls) and they were compelled to form two separate camps, for one place would not hold so great a multitude. The date of the elections was approaching, and Volumnius was recalled to Rome to conduct them, and also to advise on the general policy. Before calling upon the centuries to vote he summoned the people to an Assembly. Here he dwelt at some length upon the serious nature of the war in Etruria: he said that, even when he and his colleague were conducting a joint campaign, the war [there] was on too large a scale for any single general ... to cope with. Since then, he understood that the Umbrians and an enormous force of Gauls had swollen the ranks of their enemies. The electors must bear in mind that two consuls were being elected on that day to act against four nations. The choice of the Roman people would, he felt certain, fall on the one man who was unquestionably the foremost of all their generals. Had he not felt sure of this, he was prepared to nominate him at once as dictator”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 21: 11-15).

The scene was set for Fabius’ election as consul for the 5th time.

Situation in Rome

Livy made a laconic reference to a series of worrying portents that occurred in Rome during 296 BC:

“During that year many prodigies happened. For the purpose of averting them, the Senate decreed a supplication for two days: the wine and frankincense for the sacrifices were furnished at the expense of the public; and numerous crowds of men and women attended the performance”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 23: 1-2).

Zonaras (drawing on Cassius Dio) elaborated on the nature of these portents:

“The Romans, when they learned of [the imminent threat to Rome], were in a state of alarm, particularly since many portents were causing them anxiety:

-On the Capitol, blood is reported to have issued for three days from the altar of Jupiter, also honey on one day and milk on another (if anybody can believe it); and

-in the Forum, a bronze statue of Victory set upon a stone pedestal was found standing on the ground below, without any one having moved it; and, as it happened, it was facing in that direction from which the Gauls were already approaching.

This of itself was enough to terrify the populace, [but they] were even more dismayed by ill-omened interpretations of [the majority of] the seers. However, a certain Manius, by birth an Etruscan, encouraged them by declaring that Victory, even if she had descended [from her pedestal], had at any rate gone forward and, being now established more firmly on the ground, indicated to them mastery in the war. Accordingly, many sacrifices, too, would be offered to the gods; for their altars, particularly those on the Capitol, where they sacrifice thank-offerings for victory, were regularly stained with blood on the occasion of Roman successes and not in times of disaster. [Thus, the blood on the altar of Jupiter there foreshadowed victory.] From these circumstances, then, [Manius] persuaded them to expect some fortunate outcome, [albeit that]:

-from the honey [they could] expect disease, since invalids crave it; and

-from the milk, [they could expect] famine; for they should encounter so great a scarcity of provisions that they would seek for food of natural and spontaneous origin.

Manius, then, interpreted the omens in this way, and as his prophecy turned out to be in accordance with subsequent events, he gained a reputation for skill and foreknowledge” (‘Epitome ton istorio’, 8:1: 2-4).

A fragment of this account from Cassius Dio himself survives:

“In regard to the prophecy [of Manius], the multitude was not capable for the time being of either believing or disbelieving him:

-it neither wished to hope for everything, inasmuch as it did not desire to see everything fulfilled;

-nor did it dare to refuse belief in all points, inasmuch as it wished to be victorious;

[and so, the multitude] was placed in an extremely painful position, distracted as it was between hope and fear. As each single event occurred, the people applied the interpretation to it according to the actual result [i.e. Rome was victorious (see below) but then suffered from the predicted disease and famine], and [Manius] himself undertook to assume some reputation for skill with regard to foreknowledge of the unseen” (‘Roman History’, 8:28).

Battle of Sentinum (295 BC)

Red = Roman allies

Blue = Latin colonies founded between the second and third Samnite wars

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 268) observed that:

“The victory of Q. Fabius [Maximus] Rullianus in the battle of Sentinum, which dominates [Livy’s] account of the events of 295 BC,was one of the great turning points in Rme’s history, opening the way for her hegemony in peninsular Italy.”

This page, in which I discuss it in some detail, forms an excursus from my page on the Third Samnite War.

Dramatis Personae

Livy noted that, in 295 BC:

“... no-one felt the slightest doubt that Fabius would be unanimously elected [as consul]. ... as on the former occasion ... , he again requested that Decius might be his colleague.”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 22: 1-2).

Decius therefore entered his 4th consulship (and his third with Fabius as his colleague). Since, given the serious nature of the crisis, the services of the consuls of the previous year were also still needed:

“Appius Claudius was returned as praetor; ... [and] the Senate passed a resolution ... that Volumnius' command] should be extended for a year”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 22: 1-2).

Livy described a number of versions of the way in which these respective assignments were decided. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 283) suggested that the simplest of these was the most likely: Livy had

“... [found] it stated in some authorities that Fabius and Decius both started for Etruria immediately on entering office, no mention being made of their not deciding their provinces by lot, or of the quarrel between the colleagues that I have described”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 26: 5).

Thus, Appius, as praetor, governed Rome in the consuls’ absence and Volumnius continued to operate in Samnium as proconsul.

Furthermore, we learn from Livy that:

“... two other armies were stationed not far from the Rome, confronting Etruria:

one in the Faliscan district [north of Rome]; and

the other in the neighbourhood of the Vatican [just across the Tiber, to the west of Rome].

The propraetors:

✴Cn. Fulvius [Maximus Centumalus, the consul of 298 BC]; and

✴L. Postumius Megellus [the consul of 305 BC];

had been instructed to fix their standing camps in those positions”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 26; 15).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 288) observed that this arrangement:

“... is entirely credible: in such a great crisis, with both consuls [and their armies] away in the north, [other] forces would have been needed to guard the approach from Etruria to [Rome].”

As we shall see, Livy also named two other ex-consul who served as propraetor in this war:

✴L. Cornelius Scipio Barbatus, the consul of 298 BC, whom Fabius placed in command of the Roman camp at Camerinum (see 10: 25: 11 and 10: 26: 12); and

✴M. Livius Denter, the consul of 302 BC, whom Decius designated as propraetor (see 10: 29: 3)

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at pp. 311-3) explained that propraetorian powers could be established:

✴by the extension of an existing praetorship into the following year;

✴by the delegation of power by a serving consul or other magistrate; or

✴for privati, by the Senate and popular vote.

He observed that, since none of the four propraetors of 295 BC had held curule office in the previous year, the first possibility could be discounted here. He concluded that

✴if Livy is to be believed, then Livius had clearly received propraetorian imperium from Decius as consul (p. 311);

✴while Livy’s wording is unclear, Scipio had probably similarly received his from Fabius (see p. 312 and also Oakley’s note to this effect at p. 305); but

✴since Fulvius and Postumius had each operated separately from the serving consuls, they had probably been appointed by the Senate and popular vote as privati cum imperium (see p. 313).

Initial Roman Deployment in Etruria and Umbria

It seems that Appius had passed the the winter of 296/5 BC in the north with the army that was now to be transferred to the new consuls. Thus, according to Zonoras:

“[When Fabius and Decius] had come with speed to Etruria, and had seen the camp of Appius, which was fortified by a double palisade, they pulled up the stakes and carried them off, instructing the soldiers to place their hope of safety in their weapons”, (‘Epitome of Cassius Dio’, 8:1: 5)

Livy also reported a version of this anecdote, the point of which was to illustrate Appius’ putative reluctance to engage with the enemy. However, he placed it in one of the more complicated of his various accounts of these preliminaries, in which Fabius, who had initially underestimated the seriousness of the situation, had insisted on having sole responsibility for Etruria and marched north with only a small army:

“... to the town of Aharna (modern Civitella d’ Arno, just across the Tiber from Perusia), which was not far from the enemy, and from there went on to Appius’ camp. He was still some miles distant from it when he was met by some [of Appius’] soldiers ... Fabius asked them where they were going, and on their replying that they were going to cut wood, ... he inquired: ‘surely you [already] have a ramparted camp?’ They informed him that they had a double rampart and ditch round the camp, and yet they were in a state of mortal fear [of the enemy]. ‘Well, then,’ he replied, ‘go back and pull down your stockade, and you will have quite enough wood. They returned into camp and began to demolish the rampart, to the great terror of those who had remained in camp, and especially of Appius himself, until the news spread from one to another that they were acting under Fabius’ orders. On the following day, the camp was moved and Appius was sent back to [the safety of] Rome to take up his duties as praetor”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 25: 4).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at pp. 284-5) asserted that:

“... the historicity of the tale of the dismantling of the double palisade ... is ... doubtful. ... Although it cannot be disproved, the idea that the Claudii were not suited to war is a common motif in annalistic narrative, and disputes between Fabius and Appius, [which] are a regular theme of this book, may [also be the product of] annalistic elaboration ... .”

Livy concluded this account by recording that:

“From that time the Romans had no permanent camp: Fabius said that it was bad for an army to remain fixed in one spot, and that frequent marches and changes of position made [the men] became healthier and fitter. [The army therefore] made marches as long and as frequent as the season allowed, for the winter was not yet over. As soon as spring set in, he left the second legion at Clusium [modern Chiusi], formerly called Camars, and placed [L. Cornelius Scipio Barbatus] in charge of the camp as propraetor”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 25: 10-11).

As we shall see in the following section, it is more likely that Scipio and the second legion were stationed at Camerinum: as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 286) pointed out, Livy’s ‘Camars’, which he said was the original name of Clusium, is similar to ‘Camers’, the adjective corresponding to Camerinum.

Roman Defeat at Clusium or Camerinum

Polybius reported an early Roman defeat immediately before the major engagement at Sentinum:

“... the Samnites and Gaul ... gave the Romans battle in the neighbourhood of Camerinum, and slew a large number” (‘Histories’, 2:19: 5).

Livy reported two versions of this engagement, which he located at Clusium. In the first of these:

“... before the consuls arrived in Etruria, the Senonian Gauls came in immense numbers to Clusium with the intention of attacking the Roman camp and the legion stationed there. Scipio, who was in command [as propraetor], thinking to [make up for] the scantiness of his numbers by taking up a stronger position, marched his force on to a hill that lay between his camp and the city. [Unfortunately,] the enemy appeared so suddenly that he had had no time to reconnoitre the ground, and he continued towards the summit after the enemy had already seized it ... So the legion was... completely surrounded. Some authors say that the entire legion was wiped out there, not a man being left to carry the tidings, and that, although the consuls were not far from Clusium at the time, no report of the disaster reached them until Gaulish horsemen appeared with the heads of the slain hanging from their horses' chests and fixed on the points of their spears, whilst they chanted war-songs after their manner”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 26: 7-11).

In the second version, the assailants:

“... were not Gauls at all, but Umbrians. Nor was there a great disaster; [rather, ] a foraging party commanded by L. Manlius Torquatus, a staff officer, was surrounded and, when the propraetor Scipio sent assistance from the camp, ... the Umbrians were defeated and the [Roman] prisoners and booty were recovered, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 26: 12).

Livy then expressed the opinion that:

“It is more probable that this defeat was inflicted by Gauls rather than by Umbrians: dread of a Gallic attack ... were especially present to the minds of the citizens this year”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 26: 13).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at pp 285-6) pointed out that the Roman sources used by Polybius and Livy are unlikely to have invented a Roman defeat, and that the men who inflicted it might have included Gauls and Umbrians, although he thought that Polybius’ inclusion of Samnites here was probably a mistake. However, as Oakley pointed out (at p. 286) that, since the subsequent major engagement:

“... probably took place in Umbria (much closer to Camerinum than to Clusium), most scholars believe that Livy was mistaken, and was persuaded by [one or more] aberrant sources to transfer to Clusium a battle that, in fact, took place at Camerinum.”

Oakley also noted (at p. 282) that:

“Camerinum is said to have made an alliance with [Rome] in 310/9 BC [see my previous page], which perhaps continued unbroken. Roman concern for the protection of Camerinum would explain this [unsuccessful engagement], which almost certainly occurred in her territory.”

Course of the Battle

Tales of the battle at Sentinum reached Duris, the Greek historian who became tyrant of Samos and who was still alive at this time, Thus, Diodorus Siculus noted that:

“According to Duris, the Romans slew 100,000 men in the war with the Etruscans, Gauls, Samnites and the other allies in the consulship of Fabius [295 BC]”, (‘Library of History’, fragment, 6: 1)

Polybius recorded that, in 295 BC:

“... the Gauls made a league with the Samnites and, engaging the Romans in the territory of Camerinum, inflicted on them considerable loss. [However], the Romans, determined on avenging their reverse, advanced again a few days after with all their legions and, attacking the Gauls and Samnites in the territory of Sentinum, put the greater number of them to the sword and compelled the rest to take precipitate flight to their [respective] homes”, (‘Histories’, 2: 19: 1-4).

According to Livy:

“The force with which the consuls had taken the field consisted of four legions and a large body of cavalry, in addition to 1000 picked Campanian troopers detailed for this war, whilst the contingents furnished by the allies and the Latin League formed an even larger army than the Roman army. But in addition to this large force two other armies were stationed not far from the City, confronting Etruria; one in the Faliscan district, another in the neighbourhood of the Vatican. The propraetors, Cnaeus Fulvius and L. Postumius Megellus, had been instructed to fix their standing camps in those positions”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 26: 14-15).

At Sentinum, the Romans, led by Fabius and Decius, first set up a diversionary attack on Clusium , which:

“... drew the Etrurians from Sentinum to protect their own region”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 27: 6).

The strategist Frontinus was to use this as an example of diversionary tactics in a treatise he wrote in the 1st century AD:

“In the 5th consulship of Fabius Maximus, the Gauls, Umbrians, Etruscans, and Samnites had formed an alliance against the Roman people. Against these tribes Fabius first constructed a fortified camp beyond the Apennines in the region of Sentinum. Then, he wrote to Fulvius and Postumius, who were guarding [Rome], directing them to move on Clusium with their forces. When these commanders complied, the Etruscans and Umbrians withdrew to defend their own possessions, while Fabius and his colleague Decius attacked and defeated the remaining forces of Samnites and Gauls” ‘Stratagems’, 8:3).

This tactic does indeed seem to have been decisive: Livy observed that, had the Etruscans and Umbrians been present at the subsequent engagement at Sentinum,

“... the Romans must have been defeated”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 27: 11).

Even without them, the battle was evenly balanced until Decius:

“... spurred forward his horse to where he saw the line of the Gauls thickest and, [deliberately] rushing upon the enemy's weapons, met his death”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 28: 18).

The Roman soldiers took heart at this act of heroic self-sacrifice and the tide of battle turned.

Livy continued:

“Fabius, ... having heard of the [heroic] death of his colleague [Decius Mus], ordered [his men] ... to attack the rear of the Gallic line ..., [further] ordering that, wherever they should see the enemy's troops disordered by the charge, ... [they should] cut them to pieces ... . After vowing a temple and the spoils of the enemy to Jupiter Victor, he proceeded to the camp of the Samnites, whither all their forces were hurrying in confusion. The gates not affording entrance to such very great numbers, those [Samnites] who were necessarily excluded attempted resistance just at the foot of the rampart, and here fell Gellius Egnatius, the Samnite general. ... [Victory followed]: 25,000 enemy soldiers were slain on that day and 8,000 taken prisoner. Nor was the victory an unbloody one [for the Romans themselves]; of the army of Publius Decius, 7,000 were killed; of the army of Fabius, 1,200. Fabius, after sending men to search for the body of his colleague, had the spoils of the enemy collected into a heap and burned them as an offering to Jupiter Victor. [The body of Decius Mus was recovered] and Fabius, discarding all concern about any other business, solemnised the obsequies of his colleague in the most honourable manner, passing on him the high encomiums which he had justly merited”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 29: 15-20).

The fasti Triumphales record that, in this year that in this, his 5th, consulship, Fabius celebrated his 3rd triumph, this time over the Samnites, Etruscans and Gauls As Timothy Cornell (referenced below, 1995, at p. 362) recorded:

“... Fabius [then] returned to Rome in triumph, with an assured place in the Roman tradition as the hero of the Samnite Wars. Sentium sealed the fate of Italy [which now inevitable and progressively fell under Roman control].”

This is only the second Roman military engagement that is recorded in our surviving Greek sources (the first being the Gallic sack of Rome): a surviving fragment of the work of Diodorus Siculus (1st century BC) preserved the following fragment from the work of Duris of Samos (3rd century BC):

“In the war with the Etruscans, Gauls, Samnites and the other allies, the Romans killed 100,000 men [sic] in the consulship of Fabius, according to Duris”, (‘Library of History’, 21: fragment 6: 1).

Fabius’ Temple of Jupiter Victor

To follow

Aftermath in Upper Etruria

While battle had been raging at Sentinum:

“... Cnaeus Fulvius, the propraetor, was succeeding to the utmost of his wishes in Etruria. Not only did he carry destruction far and wide over the enemy's fields, but he fought a brilliant action with the united forces of Perusia and Clusium, in which more than 3,000 of the Perusians and Clusians [were] slain and 20 military standards taken”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 30: 2).

When Fabius emerged from Sentinum, he

“... left Decius' army to hold Etruria ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 30: 8).

Fabius himself:

“... led his own legions back to Rome to enjoy a triumph over the Gauls, the Etruscans, and the Samnites”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 30: 8).

However, this was not the end of hostilities in upper Etruria:

“After Fabius had withdrawn his army, the Perusians recommenced hostilities ... Fabius, who had marched into Etruria, killed 4,500 Perusians and took 1,740 prisoners, who were ransomed at 310 asses per head ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 31: 1-3).

Further Hostilities against the Samnites

Livy described two separate Samnite raids in the period after Sentinum:

✴On the Tyrhenian coast:

“ ... a force of Samnites descended into the territory of Vescia and Formiae, plundering and harrying as they went ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 31: 2); and

✴more, surprisingly, apparently in northern Samnium:

“... another body [of Samnites] invaded the district of Aesernum and the region round the river Volturnus”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 31: 2).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 335) observed that:

“Livy seems to imply that, [at this time], Aesernia was in Roman hands. ... this is possible, but since the site was not to be colonised until 263 BC, ... perhaps Livy should have written that the Samnites raided the middle Volturnus valley from the upper Volturnus valley around Aesernia.”

Apparently, these raiding parties were pursued by (respectively) Appius and Volumnius. Livy recorded that they were both driven into:

“... ager Stellas ... , [where] desperate battle was fought ... The Samnites lost 16,300 killed and 2,700 prisoners; on the side of the Romans 2,700 fell”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 31: 2).

Events at Rome

Livy concluded that:

“As far as military operations went, the year [of 295 BC] was a prosperous one, but it was rendered an anxious one by a severe pestilence and by alarming portents. In many places, showers of earth were reported to have fallen, and a large number of men in the army under Appius Claudius were said to have been struck by lightning. The [Sibylline] Books were consulted in view of these occurrences”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 31: 8).

He then recorded that:

“During this year Q. Fabius [Maximus] Gurges, the consul's son, who was [presumably a curule] aedile, brought some matrons to trial before the people on the charge of adultery. He obtained sufficient money out of their fines to build the temple of Venus which stands near the Circus [Maximus]”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 31: 9).

The likelihood is that the the building of this temple was the result of the consultation of the Sibylline Books.

Fabius’ Gurges Temple of Venus Obsequens

To follow [Oakley 2007 pp. 342-3]

Postumius and Atilius (294 BC)

Despite its importance, the Roman victory at Sentinum and the smaller successes that followed it were not decisive: indeed, the consuls of the following year, L. Postumius Megellus and M. Atilius Regulus (Fabius’ son-in-law), faced considerable difficulties in mopping up the remnants of Etruscan and Samnite armies. Livy recorded that:

“Samnium was assigned to both of them, following a report that the Samnites had raised three armies:

✴one that was to return into Etruria;

✴one that was to resume the devastation of Campania; and

✴one that was to defend their frontiers”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 32: 1-2).

Atilius and Postumius in Samnium

Atilius’ Initial Engagement

According to Livy:

“Postumius was [initially] detained in Rome by ill health, but Atilius marched out at once, ... intent on crushing the Samnites before they could cross the border. As it happened, he encountered them ... [near Sora ... where they] ventured ... to assault the [Roman] camp”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 32: 3-5).

It seems that the Samnites succeeded in inflicting serious Roman casualties, since the arrival of news of this setback at Rome :

“... compelled ... Postumius, although barely recovered, to take to the field. He ... [ordered] his soldiers to assemble at Sora ... ” (‘History of Rome’, 10: 33: 8).

Postumius’ Temple of Victory

Livy recorded that, before Postumius himself left for Sora, he

“... dedicated an aedes Victoriae: ... he had provided for its ... out of the money arising from fines [that he had exacted during his term of office] as curule aedile,” (‘History of Rome’, 10: 33: 9).

Two of the surviving calendar-based fasti record this dies natalis as ist August

✴ fasti Antiates Maiores: Spei Victor(is) II (To Spes; to the two Victories); and

✴fasti Praenestini: Victoriae Victoriae / virgini in Palatio Spei in/ foro Holitorio (To Victory; To Victoria Virgo on the Palatine: to Spes in the Forum Holitorium).

Thus, Postumius’ temple stood on the Palatine and shared its dies natalis with another temple there that was dedicated to Victoria Virgo (a shrine that was built beside it in 194 BC, which was dedicated by Cato the Elder in the following year). None of the surviving sources indicates when Postumius served as aedile, and nothing else is known about the history of its construction.

Postumius’ Arrival in Samnium

According to Livy, Postumius joined his army at Sora and advanced:

“... to the camp of his colleague. The Samnites, despairing of being able to make head against the two armies, retreated, ... and the consuls... proceeded by different routes to lay waste the enemy's lands and besiege their towns”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 33: 8-10).

Postumius then quickly took (the now-unknown) Milionia and Fer(i)trum.

Atilius at Luceria

Livy observed that:

“The war was by no means so easy for ... Atilius: he had been informed that the Samnites had laid siege to Luceria, and when he marched towards it, the Samnites met him on the border of the Lucerian territory”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 35: 1).

The resulting engagement seems to have been a shambles, with casualties high and morale low on both sides. The Romans had started to desert their camp, until Atilius:

“... placing himself in the way of his men, [demanded]:

‘Whither are you going, soldiers? ... not while your consul lives, shall you pass the rampart, unless victorious. Choose therefore which you would prefer: fighting against your own countrymen; or fighting against the enemy.’

... The men then began to encourage each other to return to the battle, while the centurions snatched the ensigns from the standard-bearers and bore them forward ... At the same time, [Atilius], with his hands lifted up towards Heaven and raising his voice so as to be heard at a distance, vowed a temple to Jupiter Stator, if the Roman army should rally from flight, and, renewing the battle, cut down and defeat the Samnites”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 36: 7-11).

Livy then recorded that, while Atilius was engaged near Luceria:

“... the Samnites, with a second army, attempted to seize Interamna [Lirenas], a Roman colony on the via Latina, but could not take it: ... [while pillaging the surrounding territory], they encountered the victorious consul [Atilius] returning from Luceria, .... [who destroyed them]. Atilius then summoned the owners back to Interamna to identify and receive again their property and, leaving his army there, went to Rome for the purpose of conducting the elections. When he sought a triumph, the honour was denied him, on the ground that he had lost so many men ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 36: 16-19).

Atilius’ Temple of Jupiter Stator

When Atilius invoked Jupiter Stator (above), he was reliving tactics that, according to Roman tradition, Romulus himself had employed in similar circumstances: his re-enactment was equally successful, and Roman honour was preserved.

[More]

Postumius in Etruria

According to Livy, towards the end of the consular year:

“...because there was no employment for Postumius’ army in Samnium, he led it into Etruria.

✴He first laid waste the territory of the Volsinians and, when they marched out [of their impregnable city] to protect their country, he gained a decisive victory over them, at a small distance from their own walls. 2,200 of them were slain, although the proximity of their city protected the rest.

✴He then marched into the territory of Rusellae, where the territory was ravaged and the town itself was taken. More than 2,000 men were made prisoners, and somewhat less than that number killed on the walls.

But a peace, effected that year in Etruria, was still more important and honourable than the war had been. Three very powerful cities, the chief ones of Etruria, (Volsinii, Perusia, and Arretium) sued for peace; and having agreed to furnish clothing and corn for his army, on condition of being permitted to send deputies to Rome, they obtained a truce for 40 years, and a fine was imposed on each state of 500,000 asses, to be immediately paid”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 37: 1-5).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 348) pointed out that:

“Never had Rome been so dominant in Etruria as she was in 294 BC: the victories of 295 BC had been followed up; her armies were freely penetrating the country; three major cities [Perusia, Arretium and Volsinii] had been forced to make peace; and, for the first time since 396 BC [when she had taken Veii], she had taken a major Etruscan town [Rusellae]”.

However, when Postumius:

“... demanded a triumph from the Senate in consideration of these services [at Volsinii], ... he [faced considerable opposition. However, he mounted powerful arguments to support his case]. Accordingly... with the support of 3 tribunes of the plebs (against the opposition of 7 who forbade the proceedings) and a unanimous Senate, Postumius triumphed, with the people thronging in attendance”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 37: 6-13).

Discordant Sources

Livy now lapsed into an apologia on the problems he faced in reconciling his sources for these events, for which:

“... the tradition is uncertain:

✴If we follow Claudius [Quadrigarius]:

•Postumius, after capturing several cities in Samnium, was defeated in Apulia and put to flight and (being wounded himself) was forced to take refuge with a few followers in Luceria; while

•Atilius campaigned in Etruria and obtained a triumph.

✴Fabius [Pictor] writes that:

•both consuls fought in Samnium and at Luceria;

•the army was led over into Etruria (by which consul he does not say); and

•at Luceria, both sides suffered heavy losses; in the course of the battle a temple was vowed to Jupiter Stator, as Romulus had vowed one before; but only the fanum, or place set apart for the temple, had been consecrated; this year, however, their scruples demanded that the Senate should order the erection of the building, since the state had now been obligated for the second time by the same vow”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 37: 13-16).

Since the ‘fasti Triumphales’ recorded that, in 294-3 BC:

✴L. Postumius Megellus celebrated a triumph over the Samnites and Etruscans on 27th March; and

✴M. Atilius Regulus celebrated a triumph over the over the ‘Volsones’ (presumably the Volsinians) and Samnites on the following day;

we can reasonably assume that the account of Fabius Pictor was the more accurate. Thus, given that Atilius had triumphed over the ‘Volsones’, one wonders if the treaty with the Etruscans really had been the achievement of Postumius alone.

Events of 293 BC

According to Livy, in 293 BC:

“The whole of the [Samnite] army was summoned to Aquilonia, and some 40,000 men, the full strength of Samnium, were mustered there”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 38: 5).

Adriano La Regina (referenced below, 2004, at pp. 193-4) observed, two years after their defeat at Sentinum, the war with Rome was, for the Samnites:

“ ... in an exclusively defensive phase: their army was mustered in expectation of an imminent invasion, ... which might be launched from any of Cales, Sora, Saticula or Luceria, or perhaps from more than one base. .... The fact that the Samnites were now in desperate conditions is shown by the [extreme measures that were taken to ensure that all their men of fighting age presented themselves for action, on pain of death]” (my translation]

I describe the particular characteristics of the Samnite muster at Aquilonia in my page Leges Sacratae and the Samnite Linen Legion.

Battle of Aquilonia in Samnium (293 BC)

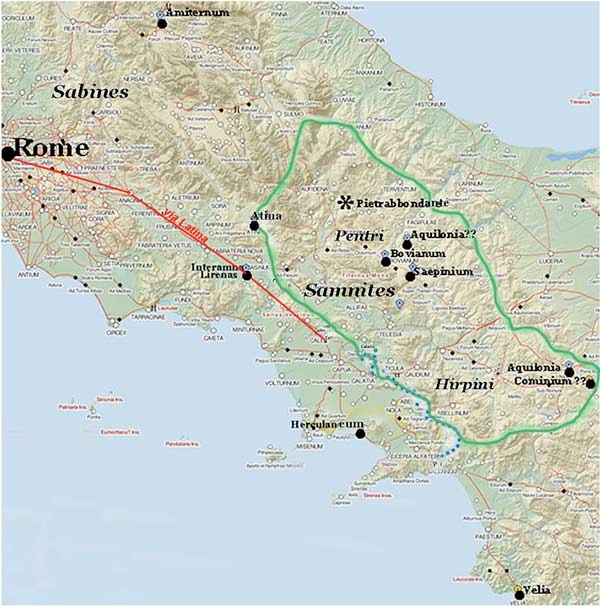

Possible locations of sites mentioned in Livy’s account of the Battle of Aquilonia (293 BC)

Black asterisk = excavated Samnite sanctuary at modern Pietrabbondante

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

According to Livy, the new consuls, L. Papirius Cursor and Spurius Carvilius Maximus, left Rome separately for Samnium:

✴Papirius left Rome with a newly-recruited army and successfully attacked the now-unknown city of Duronia (‘History of Rome’, 10: 39: 3); while

✴Carvilius assumed command of the legions that had wintered in the territory of Interamna (presumably the Latin colony of Interamna Lirenas)and advanced into Samnium. While the Samnites were preoccupied with the levy, he then stormed and captured the town of Amiternum from the Samnites (‘History of Rome’, 10: 39: 1-2)

A town called Amiternum was later documented in the alta Sabina, but this was surely too far from the theatre of war (whether in northern or southern Samnium - see below) to fit into Carvilius’ itinerary. It therefore seems more likely that this Amiternum was a Samnite centre somewhere between Interamna Lirenas and Aquilonia.

Livy (‘History of Rome’, 10: 39: 4) then noted that both consuls then ravaged the territory of Atina, before :

✴Papirius camped outside Aquilonia to confront the main body of Samnites, which was camped there); and

✴Carvilius besieged Cominium, where (we learn later) potential Samnite reinforcements were billeted.

Both consuls participated in the planning of the forthcoming battle:

“The [Roman camps were] separated by an interval of 20 [Roman miles, or some 30 km] but Carvilius was guided in all his measures by the advice of his distant colleague; his thoughts were dwelling more on Aquilonia, where the state of affairs was so critical, than on Cominium, which he was actually besieging”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 39: 7).

Papirius took on and defeated the Samnites who had mustered at Aquilonia, after which, the survivors from the Samnite infantry fled, either into their camp or into Aquilonia, while surviving cavalrymen fled to Bovianum (‘History of Rome’, 10: 41: 11). Thereafter:

✴the legate L. Volumnius Flamma took the Samnite camp (‘History of Rome’, 10: 41: 11); and

✴the other legate L. Cornelius Scipio Barbatus attacked the walled city of Aquilonia , although he had too few men to take it immediately (‘History of Rome’, 10: 41: 12-14).

At about the same time, Cominium fell to Carvilius (‘History of Rome’, 10: 43: 1-8). Aquilonia must also have fallen by then since:

“The consuls, by mutual agreement, gave up the captured cities to be sacked by the soldiery. When they had cleared out the houses they set them on fire and, in one day, Aquilonia and Cominium were burnt to the ground (‘History of Rome’, 10: 44: 1-2).

According to Livy, the consuls now held:

“... a council of war ... to settle whether the time had come for withdrawing one or both armies from Samnium. It was decided to continue the war, and to carry it on more and more ruthlessly as the Samnites became weaker, in order that the consuls might hand over a thoroughly subdued nation to those that succeeded them. As the enemy had now no army in a condition to fight in the open field, the war could only be carried on by attacking their cities ... In pursuance of this plan the consuls sent despatches to Rome giving an account of their operations and then separated, Papirius marching to Saepinum, whilst Carvilius led his legions to the assault on [Velia ?]”, (‘‘History of Rome’’, 10: 44: 6-9),

Subsequently:

✴Papirius captured Saeponium (‘History of Rome’, 10: 45: 12-14); and

✴Carvilius captured [Velia ?), the now-unknown Palumbinum, and Herculaneum from the Samnites, before marching into Etruria (‘History of Rome’, 10: 45: 9-11).

Manuscript variants such as Velia, Veletia and Vella might indicate a place called Velia (as is usually assumed), but, even if this were the correct reading, the centre in question was surely not the Greek colony on the Tyrhenian coast. Furthermore, there is no reason to think that Herculaneum was the well-known city on the Tyrhenian coast of Campania, since nothing suggests that it was giving the Romans cause for hostility at this time. In other words, if the Romans did indeed take places called Velia and Herculaneum from the Samnites in 293 BC, then these would have been now-unknown cites of these names in Samnium.

Location of this Aquilonia

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 383) set out the literary sources that document a Samnite centre called Aquilonia in the territory of the Hirpini in southern Samnium. (This centre, at modern Lacedonia, is marked at the extreme right on the map above). He observed that, since:

“Our sources mention no other Aquilonia, ... one would expect Livy to be referring to this site.”

He also noted (at pp. 383-4) that a place called Cominium Ocritum was documented in or near the Ofanto valley: on the map above, I have marked its possible location (Cominium ??) at modern Monteverde, which lays claim to it. In other words, as Oakley pointed out (at p. 386), the territory of the Hirpini could boast:

“... an Aquilonia whose location is certainly known and a Cominium whose approximate location is known ... [In order to postulate an alternative], one has to postulate the existence of other sites [in Samnium] bearing the same names.”

Furthermore, these would have to have been two walled cities some 20 Roman miles apart.

Given Livy’s references to Interamna (presumably the Latin colony of Interamna Lirenas), Atina, Bovianum (documented as the capital of the Pentri) and Saepinum, we might reasonably locate the Battle of Aquilonia in the territory of the Pentri. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 387) acknowledged that many scholars take this view, but he noted that they:

“... do not agree as to which locations [there] are most probable.”

He surveyed (at pp. 386-390) the essentially speculative nature the many hypotheses that have been proposed, which rely essentially on circumstantial archeological and epigraphic evidence. He characterised that postulated by Adriano La Regina (referenced below, 1989, at pp. 419-20) as the most influential of these: this located:

✴Aquilonia at Monte Vairano, near modern Campobasso (marked Aquilonia ?? on the map above); and

✴Cominium on Monte Saraceno, near modern Pietrabbondante, about 1 km above the famous Samnite sanctuary (marked with an asterisk on the map above), which is about 20 Roman miles from Monte Vairano.

However, the essentially insecure nature of supporting evidence is illustrated by the fact that Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2001, at pp. 142-4) proposed the reversal of these assignations. Thus, while the likelihood is that the battle took place in the territory of the Pentri, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 390) reasonably concluded that:

“... without new discoveries, the [precise] location of neither Aquilonia nor Cominium can be established beyond reasonable doubt.”

Tesse Stek (referenced below, at p. 51) observed :

“... it is not entirely sure that Livy refers to a sanctuary proper [at Aquilonia ... However,] in a recent study [by Simone Sisani, referenced below, 2001], Pietrabbondante has .. been identified with Livy’s Aquilonia. If this is correct, which is difficult to prove, this means that the traditional sanctuary at Aquilonia/ Pietrabbondante was to some extent respected by the later construction phases.”

Livy gave almost all of the credit for the Roman victory over the Samnites in 293 to the consul Papirius, and gave only a supporting role to his colleague, Spurius Carvilius Maximus: in co-ordinated engagements:

✴Papirius drove the Samnites from Aquilonia;

✴Carvilius first besieged nearby Cominius in order to prevent the Samnites billeted there from coming to the aid of the army at Aquilonia and thereafter took the city.

For Livy, this was the point at which the Samnites were finally defeated:

“Subsequently, [Papirius and Carvilius] held a council of war ... to settle whether the time had come for the withdrawal [of one or both Roman] armies from Samnium. [However], they decided that it was best to continue the war, and [indeed] to carry it on more ruthlessly as the Samnites became weaker, in order that they might hand over to the consuls who succeeded them a thoroughly subdued nation. As the enemy no longer had an army in any condition to fight in the open field, the war could only be carried on by attacking their cities: the sack of those that they captured would enrich the soldiers, while the enemy, compelled to fight for their hearths and homes, would gradually become exhausted”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 44: 6-8).

War in Etruscan and Faliscan Territory (293 BC)

Livy noted that news of the victories at Aquilonia and Cominium was received in Rome:

“... with every manifestation of delight ... These successes were not only of great importance in themselves, but they came most opportunely for Rome, as it so happened that, at that very time, information was received that Etruria had again commenced hostilities. ... The Etruscans, acting upon a secret understanding with the Samnites, had seized the moment when both consuls and the whole force of Rome were employed against Samnium as a favourable opportunity for recommencing war. Embassies from the allied states ... complained of the ravaging and burning of their fields by their Etruscan neighbours because they would not revolt from Rome. They appealed to the Senate to protect them from the outrageous violence of their common enemy, and were told in reply that the Senate would see to it that their allies had no cause to regret their fidelity, and that the day was near when the Etruscans would be in the same position as the Samnites. Still, the Senate would have been somewhat dilatory in dealing with the Etruscan question had not news arrived that even the Faliscans, who had for many years been on terms of friendship with Rome, had now made common cause with the Etruscans. The proximity of this city to Rome made the Senate take a more serious view of the position, and they decided to send the fetials to demand redress. Satisfaction was refused, and ... war was [therefore] formally declared against the Faliscans. The consuls were ordered to decide by lot which of them should lead his army from Samnium into Etruria ..., and Etruria fell to Carvilius ...”, (‘‘History of Rome’’, 10: 45: 1-10).

Carvilius consequently marched into Etruria and:

“... [made] preparations to attack [the now-unknown town of] Troilum in Etruria. He allowed 470 of its wealthiest citizens to leave the place after they had paid an enormous sum by way of ransom; and he took by storm the town with the rest of its population. Thereafter, he took five forts that occupied positions of great natural strength, in actions in which the enemy lost 2,400 killed and 2,000 prisoners. The Faliscans sued for peace, and he granted them a truce for one year on condition of their supplying a year's pay to his troops, and an indemnity of 100,000 asses f bronze coinage”, (‘‘History of Rome’’, 10: 46: 10-12).

Triumphs of 293 BC

According to Livy, while Papirius was on his way to Rome after his victories at Aquilonia and Saepinium:

“... a triumph was decreed him with universal consent; and accordingly he triumphed while [still] in office and with extraordinary splendour, considering the circumstances of those times. ... The spoils of the Samnites were inspected with much curiosity, and compared, in respect of magnificence and beauty, with those taken by his [homonymous] father,... 1,330 pounds of silver was taken in the [defeated] cities. All the silver and brass were lodged in the treasury, no share of this part of the spoil being given to the soldiers. The ill humour in the commons was further exasperated, because the tax for the payment of the army was collected by contribution [rather than from the spoils of war]. The temple of Quirinus, vowed by his father when dictator [in 325 0r possibly in 309 BC] ... [was] dedicated and adorned with military spoils. There was such a vast quantity of these that, not only were the temple and the Forum adorned with them, but they were distributed amongst the allied peoples and the nearest colonies to decorate their public spaces and temples”, (‘‘History of Rome’’, 10: 46: 2-8).

According to Pliny the Elder:

“... the Temple of Quirinus (or, in other words, of Romulus himself) one of the most ancient [temples] in Rome” (‘Natural History’ (15:36).

The temple vowed by Papirius Cursor senior and dedicated by his son was presumably built on the site of an ancient predecessor on the Quirinal.

Meanwhile, as noted above, Carvilius, who had also played an important part in the Battle of Aquilonia, had embarked on a war in which he took the now-unknown Etruscan town of Troilum and also pressured the newly-rebellious Faliscans to sue for peace. According to Livy:

“After these successes he went home to enjoy his triumph, which was:

✴less illustrious than [that of Papirius] in regard of the Samnite campaign; but

✴fully equal to it considering his series of successes in Etruria.

He brought into the treasury 380,000 asses out of the proceeds of the war and disposed of the rest:

✴partly in contracting for the building of a temple to Fors Fortuna, near the temple of that deity, that King Servius Tullius had dedicated; and

✴partly as a donative to the soldiers ... This gift was all the more acceptable to the men after the niggardliness of [Papirius]”, (‘‘History of Rome’’, 10: 46: 13-15).

Carvilius’ temple to Fors Fortuna was thus built close to an ancient one attributed to Servius Tullius, in what is now Trastevere.

Livy’s stress on Papirius’ superior contribution to the victories over the Samnites in this year is probably excessive: according to Pliny the Elder, Carvilius:

“... erected the statue of Jupiter that is [still] seen in the Capitol after he had conquered the Samnites, who fought in obedience to a lex sacrata: [this statue was] ... made from their breast-plates, greaves, and helmets ...”, (‘Natural History’, 34: 18).

The ‘fasti Triumphales’ of 293/2 BC record:

✴triumphs against the Samnites for both Carvilius (13th of January) and Papirius (13th of February); and

✴make no mention of a triumph won by either of them over the Etruscans or the Faliscans.

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 381) suggested that:

✴since the fasti preserved the actual dates, this order is probably correct; but

✴Livy is probably correct in claiming that Carvilius also triumphed over the Etruscans.

End of the War (292-90 AD)

292 BC

In the final chapter of Livy’s Book 10, he recorded that:

“The consular elections [for 292 BC] were held by L. Papirius, who declared the election of:

✴Quintus Fabius Gurges, the son of Quintus Fabius Maximus [Rullianus]; and

✴Decimus Junius Brutus Scaeva.

Papirius himself was chosen praetor”, (‘‘History of Rome’’, 10: 47: 5-6).

Unfortunately, Livy’s account of the final stages of the war is lost, although the following summary survives:

“When the consul Q. Fabius Maximus Gurges fought unsuccessfully against the Samnites [in 292 BC], and the Senate discussed his recall from the army, his father, Q. Fabius Maximus [Rullianus], asked to be allowed to save his son from humiliation. The Senate granted this when he promised to help his son as deputy, something that he duly did. With [his father’s] advice and assistance, Gurges defeated the Samnites and celebrated a triumph. Caius Pontius, the Samnite commander, walked in the [triumphal] procession and was [then] beheaded”, (‘Periochae’, 11: 1).

The ‘fasti Triumphales’ record Gurges’ triumph over the Samnites in 291 BC, presumably as proconsul (see below): since his imperium had been extended in this way, it is possible that the account of his initial failure had been exaggerated.

Zonarus, in his epitome of Cassius Dio, recorded that, while Gurges was thus engaged in Samnium in his consular year:

“The Romans ... sent out Carvilius [as legate] with Junius Brutus [to continue the campaign against the Faliscans]. Brutus worsted the Faliscans and plundered their possessions, as well as those of the other Etruscans”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 8: 1: 10, search in this link on ‘Carvilius’).

291 BC

The entries in the fasti Capitolini for the last three years of the war no longer survive, and Livy’s Book 11, which began immediately after the election of the consuls for 292 BC (above) is similarly lost. However, the so-called Chronographer of 354 AD names the consuls of 291 BC (= 463 AUC) as:

✴ ‘Megello III’ (identifiable as L. Postumius Megellus, whose earlier consulships dated to 305 and and 294 BC;

✴‘Bruto’ (identifiable as C. Junius Bubulcus Brutus, who became consul for a second time in 277 BC).

As it happens, in his surviving account of the events of 210 BC, Livy recorded that, when Q. Fulvius Flaccus, who had been appointed as dictator to oversee the consular elections, was elected as consul, he put forward two precedents, in one of which:

“... L. Postumius Megellus ... was elected consul together with C. Junius Bubulcus at the very election over which he was presiding as interrex ...”’ (‘History of Rome’, 27: 6: 8)

Finally, two surviving chapters of Book 17 of the work by Dionysius of Halicarnassus ((‘Roman Antiquities’, 17: 4-5) gave an account of Postumius’ controversial third consulship, in which we learn, inter alia, that:

✴Postumius insisted that he rather than his colleagues, should be assigned to the war with the Samnites; and

✴Quintus Fabius Gurges retained his Samnite command as proconsul (see above), but Posthumius (allegedly) expelled him from the camp at Cominium so that he could have the glory of finally taking the besieged city.

In his reconstruction of the lost fragment of the fasti Triumphales for 291-283 BC, John Rich (referenced below, at p. 248) deduced that Postumius triumphed over as consul over the Samnites and the Apulians.

The surviving fragments from Dionysius also record that Postumius:

“... captured Venusia, a populous place, along with,many other cities, of whose inhabitants 10,000 were slain and 6,200 surrendered their arms. Although he accomplished all this, he not only was not granted any mark of favour or honour by the Senate, but even lost the esteem that had been his before. For, when 20,000 colonists were sent out to ... Venusia, others were chosen to be leaders of the colony, while he, the man who had reduced the city and had made the proposal for the dispatch of the colonists, was not found worthy even of that honour”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 17: 5: 1-2).

We would expect a colony so far from Rome to have Latin rights, and this is confirmed by the fact that it was included among the 30 coloniae populi Romani (colonies of the people of Rome, or Latin colonies) that, according to Livy (‘Roman History’, 27: 10: 7), existed in 209 BC. Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, at pp. 311-2 and note 61) pointed out that many scholars argue that Dionysius’ figure of 20,000 new colonists is much too high, and that the original number of 2,000 was corrupted in transmission. However other scholars caution that this is not necessarily the case: for example, Rafael Scopacasa, referenced below, at pp. 247-8) suggested that:

“... another possibility is that [the 20,000 new colonists that Dionysius recorded] includes Italians who either lived in the town before the colonial foundation ... [or] migrated there afterwards. The possibility that many of these [putative] migrants may have come from Samnium might explain Strabo’s inclination to regard Venusia as a Samnite city [in the Augustan period].

The relevant passage from Strabo recorded that:

“... [after] Grumentum and Vertinae ... we arrive at Venusia, a notable city; but I think that this city (and those that follow in order after it as one goes towards Campania) are Samnite cities”, (‘Geography’, 6: 1: 3).

Velleius Patroculus recorded that, in 291 BC, as the Third Samnite War approached its end and (which he believed was four years after King Pyrrhus of Epirus had begun his reign):

“... [Roman] colonists were sent to ... Venusia”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 14: 6).

The foundation of this colony on the southern border of the territory of the recently-defeated Samnites, might well have worried the Italic and Italiote peoples of southern Italy.

290 BC

The so-called Chronographer of 354 AD names the consuls of 290 BC (= 464 AUC) as ‘Dentato’ and ‘Rufino’. We can cross-refer to a record of Eutropius, who recorded that, after Gurges’ victory of 291 BC:

“Publius Cornelius Rufinus and Manius Curius Dentatus, the two consuls, being sent against the Samnites, reduced their strength in some considerable battles. Thus, they brought the war with the Samnites to an end; a war which had lasted for 49 years. Nor was there any enemy in Italy that put the valour of the Romans more to the test [than the Samnites had done in these 49 years]”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 2: 9: 3).

The entry in fasti Triumphales for 290 BC also no longer survives. However:

✴an entry in the summary of Livy’s Book 11 recorded that

“When the Samnites sued for peace, the treaty was renewed for the fourth time. The consul Curius Dentatus celebrated two triumphs in one year, because he had defeated the Samnites and had also subdued the rebellious Sabines and accepted their surrender”, (‘Periochae’, 11: 5-6); and

✴an author usually identified as Aurelius Victor provided confirmation of these triumphs:

“M. [sic] Curius Dentatus first celebrated a triumph over the Samnites, whom he completely pacified as far as the Adriatic. ... He celebrated a second triumph over the Sabines”, (‘De viris illustribus urbis Romae’, 33: 1-3, my translation).

In his reconstruction of the lost fragment of the fasti Triumphales for 291-283 BC, John Rich (referenced below, at p. 248) deduced that, in 290 BC:

✴both consuls triumphed over the Samnites in 290 BC; and

✴Curius triumphed over the Sabines later in that year.

Cult of Aesculapius

In the closing lines of Livy’s Book 10, he recorded that 293 BC had seen significant victories against the Samnites, but :

“... [these] many blessings ... were hardly a consolation for one misfortune: a pestilence which ravaged both city and countryside. Its devastation was now grown portentous, and the [Sibylline] Books were consulted to discover what ... remedy the gods proposed for this misfortune.. It was discovered in these books that Aesculapius must be summoned to Rome from Epidaurus; but, the consuls were occupied with the warin that year, nothing could be done immediately, except that a supplication for one day was held for Aesculapius”, (‘‘History of Rome’’, 10: 47: 6-7).

The summary of his now-lost Book 11 records that:

“When the people suffered from a plague, envoys were sent to bring a statue of Aesculapius from Epidaurus to Rome. They brought with them a snake that had joined them in the ship, and which no doubt was a manifestation of the god; from the ship, it went to the island in the Tiber, to the place where the temple of Aesculapius has been erected”, (‘Periochae’, 11).

Gil Renburg recorded that:

“Introduced to Rome from [the Greek sanctuary at] Epidauros in response to the devastating plague of 293 BC and given a permanent home in a temple at the southern end of the Tiber Island two years later, Asclepius was among the first gods to be officially imported [to Rome] from the East ... Tradition held that he was [brought] by an ambassador, Quintus Ogulnius Gallus, who was sent by the Senate after a consultation of the Sibylline Oracles in 292 BC. revealed that the god must be enlisted in ending a plague that was devastating the population. Soon thereafter, a public sanctuary was established for Asclepius by the Senate and honoured with a dies natalis on 1 January ...”

The date of the dedication of the temple is unknown, but it would have been in or soon after 291 BC. Although remains of it have never been identified, it is widely accepted that it occupied the southern part of the island.

Writing in ca. 100 AD, Plutarch recorded that the island in the Tiber in Rome:

“... is now a sacred island over against the city, containing temples of the gods and covered walks”, (‘Life of Publicola’, 8:10).

Suetonius, who was writing at about the same time, referred to it as the ‘Island of Aesculapius’ (‘Life of Claudius’, 25: 2).

Read more:

Scopacasa R., “Ancient Samnium: Settlement, Culture, and Identity between History and Archaeology”, (2015) Oxford

Roselaar S., “Public Land in the Roman Republic: A Social and Economic History of Ager Publicus in Italy, 396 - 89 BC”, (2010) Oxford

Stek T., “Cult Places and Cultural Change in Republican Italy”, (2009) Amsterdam

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume IV: Book X”, (2007) Oxford

Renberg G., “Public and Private Places of Worship in the Cult of Asclepius at Rome”, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 51/52 (2006/7), 87-172

Sisani S., “Aquilonia: una Nuova Ipotesi di Identificazione”, Eutopia (New series), 1-2 (2001) 131-47

Cornell T., “The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (ca. 1000-264 BC)”, (1995) London and New York

Return to Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)