Veii and Fidenae

From at least the 6th century BC, Veii, the most southerly of the major Etruscan city-states, seems to have been among the most prosperous of them, with an extensive and well-developed territory that extended southwards towards the Tiber. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 347) observed that early Rome had been:

-

“... dominated by Etruscan influence and culture, and her relationship with Veii must have been particularly close. However, because both cities wished to control the trade route up the Tiber, they clashed often in the 5th century BC.”

Alexandre Grandazzi (referenced below, at p. 76) argued that it is:

-

“... very tempting to explain the incessant wars that Rome waged against Veii [throughout the 5th century BC] ... , at least in part, as a struggle for control of the ... salt fields at the mouth of the Tiber], which were, for the most part, located on the [Etruscan] side of the river ...”

This must at least partly explain why, as Louise Adams Holland (referenced below, at p. 288) observed, in the Iron Age:

-

“... [although] communities did not [generally] grow up on the banks of river, even where excellent sites were available ... [two] towns along the lower Tiber ... survived [from] the most remote legendary period: ... [these were] Rome and Fidenae, both crossing points [on the river].”

She also observed (at p. 306) that the river crossing at Fidenae was the critical point on the route from Veii along the Cremera and on to its markets in the hinterland:

-

“... less because of the break caused by the ferry itself than because the two roads [from Rome] along the Tiber (Via Tiberina, [along the right bank], and Via Salaria) intersected the Etruscan road where it met the river on each side. Veii, which could see all the Sabine hills spread out across the Tiber, had no view of the approaches to the crossing by those Tiber roads. It was chiefly for this reason that the height of Fidenae, directly opposite the opening of the Cremera valley, was essential to Veii's communications. [Observers on] the isolated height that represents the ancient citadel could forewarn the Veientines by signal if people were approaching by water or by land from any direction. ... To Veii, closed in her narrow glen, Fidenae was a prize worth fighting for in times when the bel vedere, still dear to the Italians, was valued for ... reasons [other than] ... aesthetic delight.”

Given the balance of power between Veii and Rome in the 6th century BC, it is almost certain that Fidenae was essentially under Veientine hegemony at that time, whatever claims were made to the contrary by Roman historians. However, none of our surviving sources record Fidenae as an Etruscan settlement. Pliny the Elder recorded it as:

-

✴one of the formerly celebrated towns of Latium (‘Natural History’, 3: 69);

-

✴separate from and slightly to the north of Latium (‘Natural History’, 3: 54); and

-

✴a Sabine town (‘Natural History’, 3: 107).

Henry Rackham (referenced below) translated the relevant passages at p. 53, p. 43 and p. 79 respectively. It seems likely that the Veientines’ primary interest was in the controlling the citadel at Fidenae, and that the land below it was populated by a shifting populations that included Etruscans, Sabines and Latins (including some from Rome).

Rome, Veii and Fidenae in 495 BC

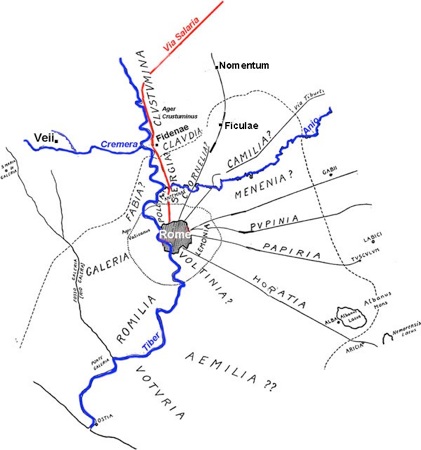

Seventeen Oldest Roman Tribes (G. C. Susini, 1959)

From Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, after p. 354)

The earliest Roman expansion northwards along the Tiber is best hypothesised on the basis of the evidence (such as it is) for the establishment of rural tribes here. The key date is 495 BC, when, according to Livy:

-

“... Appius Claudius [Sabinus Regillensis] and Publius Servilius [Priscus Structus] were chosen as consuls. ... At Rome, 21 tribes were formed”, (‘History of Rome’, 2: 21: 5-7).

This is usually taken to mean that Livy had a source for the formation of at least one new rural tribe in that year, which took the total number (including the original four urban tribes) to 21. The total remained there until 387 BC, when four new rural tribes were established for the Roman citizens who were given land that had bee confiscated from Veii after its final defeat (see below).

As illustrated in the map above, Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below) argued that, by 495 BC:

-

✴three rural tribes had been established on the left bank of the Tiber to the north of its confluence with the Anio:

-

•the Sergia;

-

•the Claudia; and

-

•the Clustumina; and

-

✴the Fabia had been established on the opposite bank of this stretch of the river.

Clustumina

The Clustumina was the only one of the first 17 rural tribes that was not named for a (presumably prominent) Roman clan:

-

✴According to the now-lost lexicon of the Augustan grammarian M. Verrius Flaccus, as summarised by Paul the Deacon:

-

“Crustumina tribus a Tuscorum urbe Crustumerium dicta est”, (‘De verborum significatu’, 48 L)

-

“The [Clustumina] tribe is named for the Etruscan town of Crustumerium”, (my translation).

-

✴According to Livy, in 499 BC:

-

“... Fidenae was besieged [and] Crustumerium taken ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 2: 19: 1-2).

Jorn Seubers, and Gijs Tol (referenced below, at p. 137) began their report of field surveys carried out in 2011-3 in the ager Crustuminus by observing that:

-

“The ancient urban centre of Crustumerium was located about 15 km north of Rome and 5 km north of contemporary Fidenae, on a hill overlooking the Tiber valley. The location of the historically attested city was established by archaeological field surveys in the 1970s ... To our current knowledge, the settlement was founded in the 9th century BC and ceased to be an urban centre at the end of the Archaic period, when it fell prey to early Roman expansionism. As such, the probably gradual abandonment of the town in the 5th century BC, which is confirmed by urban surveys, does not conflict with the historical date of its demise in 499 BC.”

Two surviving records, taken together, suggest that the area was under Roman control by 494 BC:

-

✴according to Livy, in that year, the plebs:

-

“... withdrew to the mons sacer, which is situated across the river Anio, three miles from Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 2: 32: 2); and

-

✴according to Varro:

-

“The Tribuni plebei (tribunes of the plebs) [were so-called] because they were first created from among the military tribunes in the [plebeian] secessione Crustumerina [withdrawal to Crustumerium], for the purpose of defending the [political interests of] plebs”, (‘On the Latin Language’, 6: 18, translated by Roland Kent, referenced below, at p. 79).

It thus seems that the Clustumina was established for Romans settled on land that was confiscated after the fall of Crustumerium: since it was the first of the rural tribes to be named for its location, we might reasonably assume that it was the last of the 17 rural tribes to be founded, and that this occurred in 495 BC. From at least this time, a significant number of Romans would have shared the ager Crustuminus with other Latin and Etruscan communities.

Claudia

Appius Claudius Sabinus Regillensis, the consul of 495 BC was the first securely recorded member of the gens Claudia, for whom the Claudia tribe was named. Dionysius of Halicarnassus (ca. 7 BC) recorded a tradition in which, in 504 BC, during a war between the Romans and an alliance of Sabines, Fidenates and Camerians:

-

“A certain Sabine, Titus Claudius by name, who lived in a city called Regillum, a man of good family and influential for his wealth, deserted to [the Romans], bringing with him many kinsmen and friends and a great number of clients, who removed with their whole households, not less than 500 of whom were able to bear arms. ... ; and, by adding no small weight to [the Roman] cause, [Claudius] was looked upon as the principal instrument in the success of this war. In consideration of this, the Senate and people enrolled him among the patricians and gave him leave to take as large a portion of the city as he wished for building houses; they also granted to him from the public land the region that lay between Fidenae and Picetia [probably Ficulae], so that he could give allotments [of land] to all his followers. In the course of time, these Sabines were placed in a new tribe, the Claudia, a name which it continued to preserve down to my time”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 5: 40: 3-55).

It is likely that this tradition had grown up in order to explain the establishment of the Claudia for Roman settlers on the land between Fidenae and Ficulae: this tribe would have existed in 495 BC, and might have been formed in that year and given the cognomen of Appius Claudius Sabinus.

Support for this hypothesis exists in the form of a now-lost funerary inscription (CIL I2 1709) from Foggia (in southern Italy), which commemorated T. Terentius, ‘dictator Fidenis quater’, who belonged to the Claudia. Edward Bispham (referenced below, at pp. 380-1) suggested that Fidenae had finally been incorporated in ca. 60 BC, prior to which it had:

-

“... enjoyed no corporate existence [within the Roman state] since the 4th century BC.”

In other words:

-

✴after its fall to Rome the 4th century BC (see below), Fidenae had probably survived only as an insignificant settlement; and

-

✴when it was formally incorporated in ca. 60 BC, its newly-enfranchised inhabitants were probably assigned to the Claudia because this was the tribe of existing citizens settled in the surrounding area.

Sergia

The likelihood is that the Sergia tribe was established for settlers on land that was controlled by the gens Sergia. Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 40) suggested that:

-

“The clue to the location [of the Sergia might well lie] in the cognomen Fidenas, which was given to L. Sergius, consul in 437 and 424 BC and military tribune with consular powers in 433, 429 and 418 BC. Livy [at ‘History of Rome’, 4: 17: 7, in a passage concerning the events of 437 BC], has a vague suggestion of [later] military victories as the explanation of this cognomen, but more probable explanation ... is to be found in Sergius’ activity, reported under 428 BC., in a senatorial commission to investigate the participation of the Fidenates in raids on Roman territory [see below].”

Support for this hypothesis might be found in another passage by Livy (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 6), in which he named the members of this commission as:

-

✴L. Sergius;

-

✴Q. Servilius; and

-

✴Mamercus Aemilius.

Unfortunately, the entries in the fasti Capitolini are missing for the period 449- 423 BC, so we cannot be sure that Sergius was given the cognomen Fidenas in 428 BC. However, it is interesting to note that the earliest surviving records of this cognomen Fidenas in the fasti both date to 418 BC, when:

-

✴L. Sergius C.f. C.n. Fidenas was military tribune for the third time; and

-

✴Q. Servilius P.f. Sp.n. Priscus Fidenas was dictator for the second time (having been dictator for the first time in 435 BC).

Ross Taylor (as above) suggested that:

-

“... Sergius (and, perhaps, Servilius too) was placed on the commission because his property and that of his clients had been molested in the raids.”

It is certainly true that there must have been a rural tribe here before the establishment of the Clustumina and the Claudia in ca. 495 BC, and the shared cognomina of the two commissioners of 428 BC might well indicate that both the Sergii and the Servilii were well-established in the area by that time. Furthermore, the cognomen is recorded again on eight occasions before 368 BC, and in every case it belonged to a member of the gens Sergia or the gens Servilia. Thus, as Ernst Badian (referenced below, at p. 202) commented in his review of Lily Ross Taylor’s book:

-

“... on [the location of the] Sergia, she well may be [right: in any case] we can do no better.”

Fabia

Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 41) argued that the site of the Fabia tribe is suggested by:

-

“... the legend that the gens Fabia assumed full control of the war against Veii.”

I discuss this legend below: for the moment, we might simply note that, according to tradition, the gens Fabia assumed responsibility of the ongoing war with Veii in 479 BC, and established a fortified base on the southern bank of the Cremara. Lily Ross taylor (as above) reasonably argued that:

-

“The Fabia tribe [probably embraced] the land [occupied by] the Fabii and their clients, [and this tradition suggests that it] adjoined the territory of Veii south of the Cremera ... [If so, then the Fabia] was the northernmost of the tribes on the right bank [of the Tiber].”

War with Veii (483 - 474 BC)

As Timothy Cornell (referenced below, at p. 311) observed:

-

“The most that we can say about [this war] is that Veii had the best of it. ... the Veientines [advanced] into Roman territory and [occupied] a fortified post on the Janiculum. It was in an attempt to counter this move that the Fabian clan ... [famously] marched out in 479 BC to occupy a small frontier post on [a tributary of the Tiber known as] the ... Cremera. Two years later, they suffered a catastrophic defeat, [in which] the entire clan .. was wiped out, with the exception of a single youth who escaped to keep alive the name of the Fabii.”

The context in which this war was fought is found in the fact that, as Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at p. 195) pointed out:

-

“During each of the seven years 485-79 BC, one of the two consuls was a Fabius. Such domination of the consulship by a single family is unparalleled in the consular fasti of the Republic.”

Livy recorded inconclusive wars with Veii in this period in:

-

✴483 BC (‘History of Rome’, 2: 42: 9);

-

✴482 BC (‘History of Rome’, 2: 43: 1);

-

✴481 BC ((‘History of Rome’, 2: 43: 2); and

-

✴480 BC ( ‘History of Rome’, 2: 46-47).

According to Livy, K. Fabius Vibulanus was elected as consul for the third time in 479 BC. Since the Veientine war continued, he proposed in the Senate that:

-

“A permanent body of defenders rather than a large one is required ... for the [intermittent] war with Veii. [I therefore suggest that[ you attend to the other wars, and assign to the Fabii the task of opposing the Veientes. We undertake that the majesty of the Roman name shall be safe in that quarter. It is our purpose to wage this war as if it were our own family feud, at our private costs: the state may dispense with furnishing men and money for this cause”, (‘History of Rome’, 2: 48: 8-9).

Livy then recorded that this offer was accepted and the Fabii established a fortified camp on the southern bank of the Cremera. However, in 477 BC, they were drawn across the Cremera and into an ambush, in which they:

-

“... were all killed, and their fort was stormed. 306 men perished, as is generally agreed; only one, who was little more than a boy, survived to maintain the Fabian stock ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 2: 50: 11).

The likelihood is that this legend was told to account for the fact that the next Fabian consul recorded in the fasti Capitolini was Q. Fabius Vibulanus in 467 BC, who was probably thought to have been the only survivor of the disaster of 477 BC.

According to Livy, this war with Veii ended in 474 BC when:

-

“...a truce for 40 years was granted [to the Veientines] at their solicitation, and corn and a cash indemnity were exacted of them”, (‘History of Rome’, 2: 54: 1).

Livy made this sound like a Roman victory but, as Timothy Cornell (referenced below, at p. 311) observed, the truce:

-

“... left the Veientines firmly in possession of [the citadel at] Fidenae ... , [which] became the focus of [the next war between them].”

Wars with Veii and Fidenae (438 - 426 BC)

Red road = Via Nomentina; Green road = Via Salaria

Livy’s is the only surviving narrative account of the Romans wars with Veii and Fidenae in this period, a problem that is compounded by the fact that the relevant entries in both fasti Capitolini and the fasti Triumphales. As Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at p. 243 BC), pointed out, if Livy’s account is accurate, then there were two distinct period of war between Rome and Veii for control of Fidenae:

-

✴one in 437-5 BC; and

-

✴the other in 426 BC;

both of which ended in the Romans’ capture of Fidenae. In the following section, I summarise Livy’s account of each of these wars, as a preliminary to a more detailed analysis.

Livy’s Account of the War of 437-5 BC

Cause of the War

According to Livy, the event that gave rise to this war occurred during the magistracy of three consular tribunes: Mam. Aemilius Mamercinus, L. Quinctius Cincinnatus and L. Julius Iullus (438 BC), when:

-

“... Fidenae, a Roman colony, defected to Lars Tolumnius and the Veientines. A greater wickedness was added to this defection: on Tolumnius’ orders, the Fidenates killed the [four] Roman legati [usually translated as ambassadors], C. Fulcinius, Cloelius Tullus, Sp. Antius, and L. Roscius, who were seeking the reason for this new policy”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 17: 1-2).

In later passages (below), Livy identified Lars Tolumnius as the king of Veii.

As Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at p. 243) pointed out, ‘Lars Tolumnius‘ might well have been the Latinised form of the name of an actual king of Veii. Furthermore, the claim that four Roman ambassadors were murdered at Fidenae is almost certainly authentic:

-

✴Livy recorded that statues of them:

-

“... were set up at public expense on the Rostra in the forum”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 17: 6).

-

✴Cicero recorded that:

-

“Lar Tolumnius, the king of Veii, murdered four ambassadors of the Roman people at Fidenae, whose statues were standing in the Rostra until within my recollection [i.e., until their removal when the Rostra was rebuilt in the early 1st century BC]”, (‘Philippics’, 9: 4).

-

Cicero named them as Tullus Cluvius, L. Roscius, Sp. Antius and C. Fulcinius

-

✴Pliny the Elder recorded that:

-

“Among the most ancient [public statues erected at Rome] are those of Tullus Clœlius, L. Roscius, Sp. Nautius, and C. Fulcinus, near the Rostra, all of whom were assassinated by the Fidenates while on their mission as ambassadors”, (‘Natural History’, 34: 11).

There is thus no particular reason to doubt that these events took place in this year. On the other hand, Livy’s claim that Fidenae was a Roman colony in 438 BC cannot be corroborated from our surviving sources. It is true that, by 495 BC, Roman citizens were settled in two adjacent tracts of land:

-

✴one along the right bank of the Tiber, to the south of its confluence with the Cremera (assigned to the Fabia tribe); and

-

✴another along the left bank of the Tiber and the Roman Via Salaria (assigned to the Sergia, the Claudia and the Clustumina).

However, as Timothy Cornell (referenced below, at p. 311) observed, the 40-year truce agreed between Rome and Veii:

-

“... that was made in 474 BC left the Veientines firmly in possession of Fidenae , which they must already have controlled before the Cremera disaster. Thus, Fidenae became the focus of ...[the war between Rome and Veiil that] broke out in 437 BC ... ”

Livy had made no reference before this point to the circumstances in which Fidenae had been made a Roman colony, and Robert Ogilvie (referenced below, at p. 284) reasonably argued that his claim that it was a colony at this point at this point:

-

“... looks like special pleading. It would be galling to Roman pride to accept that a town so small and so near should have retained its independence so long. Rome's subsequent atrocities against [Fidenae] could be sententiously justified if [the settlement there could be represented] as a disloyal colony.”

-

Roman Victory in 437 BC

-

According to Livy, the seriousness of these events caused the Romans to revert to a pair of consuls in 437 BC: M. Geganius Macerinus and L. Sergius (who later acquired the cognomen Fidenas - see above):

-

“[Sergius] was the first who fought a successful action [against Tolumnius] on this side of the Anio. His victory was by no means a bloodless one; there was more mourning [among the Romans] for their countrymen who were killed [in victory] than joy over the defeat of the enemy”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 17: 8).

It seems that the serving consuls were deemed to be incapable of dealing with the resulting emergency:

-

“Owing to the critical aspect of affairs, the Senate ordered Mamercus Aemilius [Mamercinus] to be proclaimed dictator. He chose as his master of horse L. Quinctius Cincinnatus, who had been his colleague in the college of consular tribunes the previous year, a young man worthy of his father. A number of war-seasoned veteran centurions were added to the force that had been levied by the consuls in order to replace the number of those lost in the late battle. [Mamercinus] ordered [L.] Quinctius Capitolinus and M. Fabius Vibulanus to accompany him as seconds in command”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 17: 9-10).

-

Mamercinus drove the Veientine and Fidenate armies back across the Anio and to the walls of Fidenae, where they were joined by a contingent from Falerii. (This marks the first appearance in our surviving sources of Falerii, which was located some 35 km north of Veii). Mamercinus established his camp in a defensive position at the confluence of the Tiber and the Anio and remained there until he saw the agreed signal that the omens were favourable, at which point he marched on Fidenae. Nevertheless, despite the number of experienced officers that apparently fought under Mamercinus, Livy’s account of the ensuing battle :

-

“... a military tribune [serving in the cavalry] called A. Cornelius Cossus, who was extraordinarily handsome, equally strong and courageous, and mindful of his birthright. He had inherited a glorious name that he greatly enhanced and bequeathed to his descendants. .... [When he saw Tolumnius on horseback creating mayhem among the Roman ranks], he charged with levelled spear against him and, having struck and unhorsed him, leapt ... to the ground. As [Tolumnius] was attempting to rise, Cossus ... [killed him] ... Then he despoiled the lifeless body, cut off the head, stuck it on his spear and, carrying it in triumph, routed the enemy, who were panic-struck at the king's death”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 19: 4-5).

This decided the outcome of the battle, and Mamercinus duly led his army to victory. According to Livy:

-

“Successful in all directions, [Mamercinus] returned home to enjoy the honour of a triumph granted him by decree of the Senate and resolution of the people. ... By order of the people, a crown of gold, a pound in weight, was made at the public expense and placed by [Mamercinus] in the Capitol as an offering to Jupiter”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 1-4).

One might reasonably assume that this triumph marked the Romans’ recapture of their putative colony at Fidenae. However, as we shall see, Livy noted that, in 435 BC:

-

“... the Fidenates, who at first had kept to the mountains or their walls, actually came down into Roman territory, intent on plunder”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 21: 7).

Thus, if Mamercinus really did recover Fidenae in 437 BC, then the rebels must have quickly recovered it in an engagement that Livy did not record.

-

Cossus and the Spolia Opima in 437 BC

-

As we have seen, Livy had devoted most of his account of Mamercinus’ victory in 437 BC to the exploits of Cossus, the military tribune who had killed Tolumnius in single combat. In his account of Mamercinus’ subsequent triumph, Livy noted that:

-

“By far the finest sight in the [triumphal] procession was [the military tribune], Cossus, bearing the spolia opima of [Tolumnius], whom he had killed [in single combat]. The soldiers sang rude songs in his honour and placed him on a level with Romulus. In a solemn ceremony, he dedicated the spoils in the temple of Jupiter Feretrius, placing them near the spoils of Romulus, which were the first to be called opima and were the first and (until that time) the only ones known as spolia opima. All eyes were turned from [Mamercinus’] chariot to [Cossus], who almost monopolised the honours of the day”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 2-3).

-

-

Livy then seems to throw doubt on this account:

-

“[In stating] that A. Cornelius Cossus was a military tribune when he brought the secunda spolia opima to the temple of Jupiter Feretrius, I followed all previous authorities. However, [there are two problems with this received wisdom] ... :

-

✴[spoils of war] are properly deemed to be spolia opima only if dux duci detraxit (they have been stripped from a commander by a commander), and we [Romans] know of no commander other than the one under whose auspices the war is conducted; and

-

✴the very words inscribed upon the spoils [that Cossus took from Tolumnius] ... show that Cossus captured them as consul.

-

When I heard that Augustus Caesar, the founder or renewer of all the temples had entered the shrine of Jupiter Feretrius (which he rebuilt when it had crumbled with age) and read the inscription on the linen corselet, I thought that it would be prope sacrilegium (almost sacrilegious to deprive Cossus of Caesar (the restorer of that very temple) as the witness to his spoils”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 5-7).

Livy’s reference to ‘Caesar Augustus’ indicates that this passage was written after 13 January 27 BC, when the erstwhile triumvir Octavian (who had been posthumously adopted by Julius Caesar in 44 BC) was officially named as Augustus, and it is usually assumed that it was a late addition to the original text.

As we shall see, Livy then observed that Cossus had fought under his own auspices on two occasions:

-

✴as consul in 428 BC; and

-

✴as consular tribune and master of horse in 426 BC.

However, he then asserted that:

-

“... I believe that [any speculation about 437 or 426 BC] is useless. The fact remains that ... [Cossus]:

-

✴placed the newly-won spoils ... before Jupiter (to whom they were consecrated), with Romulus looking on (and these two witnesses are to be dreaded by any forger); and

-

✴he described himself in the inscription as: ‘A. Cornelius Cossus: Consul’”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 11).

We might therefore have expected Livy Livy to make corresponding changes to his subsequent accounts of the events of 428 and 426 BC. However, he failed to do so, with the result that his account is inconsistent in its dating of Cossus’ dedication of the spolia opima. I pick this up in my accounts of each of these years and again in the closing section.

Events of 436-5 BC

After a digression in which Livy discussed the possibility that Cossus had actually killed Tolumnius and dedicated the spolia opima in either 428 or 426 BC, as discussed below), Livy turned to the events of 436 BC, when M. Cornelius Maluginensis and L. Papirius Crassus were consuls and:

-

“... [Roman] armies invaded Veientine and Faliscan territory, driving off men and beasts as booty. Nowhere in the countryside did they find the enemy, nor was there any opportunity for fighting. However, the cities [of Veii and Falerii] were not besieged, because a plague attacked the people ... ”,(‘History of Rome’, 4: 21: 1-2).

The plague continued into 435 BC, when:

-

“... C. Julius [Iullus] (for the second time) and L. Verginius were consuls, causing such fear ... in the City and the countryside that no one went beyond Roman territory to plunder, and nor did the senators or plebeians have any thought of making war”,(‘History of Rome’, 4: 21: 6)

It was at this point, less than two years after Mamercinus’ putative triumph, that:

-

“... the Fidenates, who at first had kept to the mountains or their walls, actually came down into Roman territory, intent on plunder. Then they summoned an army from Veii (although neither Rome’s misfortunes nor the prayers of their allies could drive the Faliscans into renewing war). The Fidenates and the Veientines] crossed the Anio, setting up their standards not far from the Colline Gate ”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 21: 7-8).

At this point, according to Livy:

-

“The consul Julius stationed his troops on the rampart and the walls [while his colleague], Verginius, convened the Senate in the temple of Quirinus, [presumably the predecessor of the temple of Quirinus here that was dedicated in 325 BC]. They decreed that Q. Servilius should be nominated dictator:

-

✴according to one tradition, he was surnamed Priscus,

-

✴according to another, Structus.

-

Verginius, ... on gaining his [colleague’s] consent, nominated the dictator at night, [as was the usual practice, and he, in turn], he appointed Postumius Aebutius Helva as his master of horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 21: 9-10).

This dictator was almost certainly the Q. Servilius Priscus Fidenas who is recorded in the fasti Capitolini as dictator for the second time in 418 BC: he presumably acquired the agnomen ‘Fidenas’ after this first dictatorship in 435 BC.

Fall of Fidenae (435 BC)

According to Livy, Servilius:

-

“... ordered everyone able to bear arms to muster at the Colline Gate at dawn. The standards were taken from the treasury and brought to the [him]. Meanwhile, the enemy withdrew to higher ground. [Servilius] advanced with arms at the ready and engaged with Etruscan forces not far from Nomentum. He put them to flight there and then drove them into the city of Fidenae ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 22: 1-2).

He then laid siege to Fidenae but:

-

“... owing to its elevated positron and strong fortifications, [it] could not be carried by assault, and the blockade was quite ineffective because ... a lavish supply [of corn] had been stored up beforehand. So all hope of either storming the place or starving it into surrender was abandoned”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 22: 3).

Servilius concentrated his bombardment on the most heavily defended part of the walls while organising the secret construction of a tunnel into the city from the opposite side:

-

“At last the hill was tunnelled through and the way lay open from the Roman camp up to the citadel. While the attention of the Etruscans was being diverted from their real danger by feigned attacks, the shouts of the enemy above their heads showed them that [Fidenae] was taken”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 22: 6).

Truce with Veii ?

Strangely, Livy did not record anything more about the fall of Fidenae and the subsequent fate of Veii at this point of his narrative. However, in his account of the Romans’ declaration war on Veii in 427 BC (below), he explained that:

-

“There had been recent battles with the Veientines at Nomentum and Fidenae, and indutiaeque inde, non pax facta (a truce had been made, rather than a lasting peace), but the Veientines had renewed hostilities before the term of truce had expired”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 12-14).

This presumably referred to the ending of the hostilities that are described in this section, which suggests that:

-

✴the state of war between Rome and Veii ended in 435 BC with the agreement of a formal truce;

-

✴the war was resumed in 427 BC because the Romans alleged that the Veientines had violated this agreement.

Livy’s Account of the Interwar Period (434 - 427 BC)

Veii’s First Unsuccessful Appeal for Help from the Etruscan League (434 BC)

According to Livy, in 434 BC, following the fall of Fidenae:

-

“There was consternation in Etruria:

-

✴the Veientines, [in particular], were terrified by the fear of a similar fate; and

-

✴the Faliscans [feared retribution because] they had started the war in alliance with the Fidenates, albeit that they had not helped them in their revolt.

-

The two states consequently sent ambassadors around duodecim populos (the twelve peoples) and obtained their agreement to the convening of omni Etruriae concilium (a council of all the Etruscans) at the fanum Voltumnae (shrine of Voltumna)”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 23: 4-5).

This is the first time that Livy identified the national shrine of the Etruscans by this name. Since there was now a real danger that a wider Etruscan war would break out, Mam. Aemilius Mamercinus was appointed to his second dictatorship, and he appointed A.Postumius Tubertus as his master of the horse. However:

-

“The affair ended more quietly than anyone had expected: it was reported by traders that the Veientines had been denied help [from their fellow -Etruscans] and ordered to finish the war with their own resources, since it had been their idea to start it. Nor were they to seek as allies in their misfortune from those men with whom they had not shared their original hopes, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 24: 1-2).

The implication seems to be that Lars Tolumnius had not consulted the other eleven principal members of the League before inciting the putative rebellion at Fidenae and ordering the murder of the Roman ambassadors. When news arrived in Rome that the Etruscan threat had not materialised, Mamercinus resigned his dictatorship.

Veii’s Second Unsuccessful Appeal for Help from the Etruscan League (432 BC)

According to Livy, the outbreak of plague in Rome (which he had first mentioned in 436 BC) continued into 433 BC, when:

-

“A temple was vowed to Apollo on behalf of the people’s health. On the advice of the [Sibylline] books, the duoviri [college of two magistrates] did many things to placate the anger of the gods [in an attempt to end the epidemic]. Nevertheless, a great disaster was sustained in both the city and countryside, as men and cattle perished indiscriminately’, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 25: 3-4).

At this time, the Romans learned that (presumably because of their dire situation):

-

“Projects of war were [being] discussed:

-

✴in the councils of the Volsci and the Aequi; and

-

✴in Etruria at the fanum Voltumnae. There, the question was adjourned for a year and a decree was passed that no [subsequent] council should be held until the year had elapsed, in spite of the protests of the Veientines, who declared that they now faced the fate that had [already] overtaken Fidenae”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 25: 6-9).

The plans of the Volsci and the Aequi culminated to the defeat of their combined armies on the Algidus in 431 BC, after which, Livy was able to proclaim that, in 429 BC, for the moment:

-

“ As far as the Romans were concerned, it was peaceful everywhere”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 3).

Consulship of A. Cornelius Cossus (428 BC)

The consuls for 328 BC were:

-

✴A. Cornelius Cossus (whom Livy credited with having killed Tolumnius as military tribune in 437 BC); and

-

✴T. Quinctius Poenus.

Livy recorded that, in this year:

-

“The Veientines raided on Roman territory. and there was a rumour that some youths from Fidenae had taken part in it”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 5).

Three commissioners:

-

✴L. Sergius (presumably the consul of 437 BC);

-

✴Q. Servilius (presumably the dictator of 435 BC); and

-

✴Mam. Aemilius (presumably the dictator of 437 and 434 BC);

-

were sent to Fidenae investigate the apparent involvement in them of the Fidenates. (I discussed this investigation above in relation to the location of the Sergia tribe). As a result of their investigations:

-

✴those Fidenates who could not explain why they had been away from Fidenae during the time of the raids were banished to Ostia; and

-

✴a number of new Roman settlers at the putative colony at Fidenae were given land that had belonged to men who had fallen in the earlier war.

Although Cossus and Poenus had dealt with Fidenae, Livy recorded that:

-

“The anger against the Veientines was postponed until the following year...”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 12).

-

Cossus and the Spolia Opima in 428 BC

In his account of Cossus’ consulship (above), Livy:

-

✴made no reference to the spolia opima; and

-

✴explicitly stated that the Romans had not engaged with the Veientines in this year (in which case, Tolumnius could not have been killed in that year).

However, as we have seen, in a passage that he had added to his original account of the events of 437 BC, he had noted that no less a person than ‘Augustus Caesar’, who had recently seen the inscription of the corslet dedicated as spolia opima in the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius and reported that it had named the man who had dedicated it as: ‘A. Cornelius Cossus: Consul’. Although Livy could hardly have contradict this outright, he had mused that:

-

“Everyone must judge for himself how the [discrepancy between the available information] came about, [since:

-

✴both the ancient annals and the linen books of magistrates that are preserved in the temple of [Juno] Moneta (which [C.] Licinius Macer frequently cites as his authority) record that A. Cornelius Cossus was consul (together with T. Quinctius Poenus) nine years [after his military tribuneship] ... ; but

-

✴this famous battle cannot be transferred to this later date ... [because], during the three years around the time of Cossus’ consulship, war was impossible owing to pestilence and famine, to the extent that some of the annals ... supply nothing but the names of the consuls”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 8-9).

I discuss the implications of this below.

Preliminaries to the Renewal of War with Veii and Fidenae (427 BC)

According to Livy, Rome was now beset by drought and large sections of the population responded by turning to foreign superstitions:

-

“War with Veii was therefore postponed until 427 BC, when C. Servilius Ahala and L. Papirius [Mugilanus or Cursor] were consuls. Even then, the formal declaration of war and the despatch of troops were delayed on religious grounds; it was considered necessary that the fetials should first be sent to demand reparations [as an alternative to war]”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 12-13).

Livy then explained why the fetials’ services were needed:

-

“There had been recent battles with the Veientines at Nomentum and Fidenae, and indutiaeque inde, non pax facta (a truce had been made, not a lasting peace), but the Veientines had renewed hostilities before the days of truce had expired”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 12-14).

As mentioned above, this presumably referred to the ending of the war of 438-5 BC. Fetials were duly sent to Veii, but when they:

-

“... sought reparation after taking the customary oath, their words were ignored”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 14).

The fetials’ return to Rome with the news that the Veientines had refused redress would usually have triggered a declaration of war. However:

-

“A question then arose as to whether war should be declared by the mandate of the people, or whether a resolution passed by the Senate was sufficient. The [plebeian] tribunes threatened to obstruct the levying of troops and succeeded in forcing the consul Quinctius [sic] to refer the question to the people. The centuries decided unanimously for war. The plebs then gained a further advantage in preventing the election of consuls for the next year”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 30: 15-16).

(Note that ‘the consul Quinctius’ presumably meant T. Quinctius Poenus, who had actually been the consul of the previous year.)

Defeat of Veii and Fall of Fidenae (426 BC)

Because of pressure from the plebs, four consular tribunes were elected for 426 BC. War was duly declared, following which:

-

✴three of the consular tribunes marched against Veii; while

-

✴the fourth, Cossus (who had been consul in 428 BC) took charge of the city.

The conduct of the war was disastrous, and the people:

-

“... demanded a dictator ... Here too, a religious impediment arose, since only a consul could nominate a dictator. The augurs were consulted and removed the impediment: [Cossus duly] nominated Mam. Aemilius [Mamercinus] as dictator [for the third time] and he appointed Cossus as his master of horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 31: 4-5).

According to Livy:

-

“Elated by their success, the Veientines sent envoys round to the peoples of Etruria, boasting that they had defeated three Roman generals in a single battle. However, they could not induce the national council to join them, although they collected from all quarters volunteers who were attracted by the prospect of booty. The Fidenates alone decided to take part in the war”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 31: 8-9).

Before joining the Veientines, the Fidenates:

-

“... as though they thought it impious to begin war without committing a crime, stained their weapons with the blood of the new colonists, as they had previously with the blood of the Roman legati ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 31: 8-9).

Fidenae now became the headquarters of the enemy army. Mamercinus duly marched on Fidenae with two of the consular tribunes in support:

-

✴Cossus (who was also master of horse) led the cavalry; and

-

✴T. Quinctius Poenus, who commanded a reserve army that was stationed in the hills above the city.

Livy recorded that:

-

“The Romans had immediately shattered the foe at the first onset [outside Fidenae], when suddenly, the gates of Fidenae were opened and there burst forth a strange battle line that had never before been heard of or seen. A huge mob, armed with fire and blazing torches, lit up everything as they rushed against the enemy, seemingly driven by frenzied madness. For a moment this unusual kind of fighting terrified the Romans. Then [Mamercinus] summoned [Cossus] and the cavalry and sent for Quinctius to come from the mountains [with the reserves]”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 33: 1-3).

Mamercinus successfully halted the initial panic by encouraging his men to pick up the firebrands and use them against the enemy, while Cossus:

-

“... devised a new cavalry stratagem: ordering his men to release their horses’ reins, he himself led the way and, in his spurs, he was carried right into the midst of the flames on his unbridled horse. The rest of the horses were then also spurred on, bearing their riders with free rein into the enemy. Dust arose, mingled with smoke, obscuring the sight of both men and horses, but the sight that had terrified the soldiers held no terror for the horses and, wherever the cavalry advanced, they spread

-

destruction like toppled buildings”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 33: 7-9).

At this point, Quinctius arrived with the reserves and. as the Etruscans fled in all directions, he captured the defenceless city itself while Mamrcinus capture the enemy camp outside it:

-

“Then he entered the walls [of Fidenae] and marched to the citadel, where he saw the mob of fugitives rushing. The slaughter in the city was not less than there had been in the battle, until, throwing down their arms, the [enemy survivors] surrendered to Mamercinus and begged that at least their lives might be spared. The city and camp were plundered. ... Mamercinus led his victorious army, laden with spoil, back in triumph to Rome. After ordering Cossus to resign his office as master of horse, he himself resigned the dictatorship on the 16th day after his nomination, surrendering amidst peace the sovereign power that he had assumed at a time of war and danger”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 34: 3-6).

Livy (‘History of Rome’, 4: 35: 2) recorded that, at the start of 425 BC, the Veientines were granted a truce of 20 years.

A. Cornelius Cossus and the Spolia Opima in 426 BC

In his account of the start of the battle of 426 BC, Livy imagined Mamercinus restoring the Romans’ morale by reminding them that:

-

“... they now had:

-

✴as dictator, the same Mamercus Aemilius who had defeated the combined forces of Veii and Fidenae, supported by the Faliscans, at Nomentum [sic]; and

-

✴as his master of the horse, ... the same Aulus Cornelius who, as military tribune, had killed Lars Tolumnius, king of Veii, in full sight of both armies, and had carried the spolia opima to the temple of Jupiter Feretrius”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 32: 4-5).

This passages clearly belonged to the original text and had not been updated in the light of the new information, which suggested that Cossus had killed Tolumnius as consul. As we have seen, Livy remained concerned that he could find no record of any fighting between Rome and Veii in the period of Cossus’ consulship, and he had had tentatively mad his own suggestion as to how this difficulty might be resolved:

-

“The second year after Cossus’ consulship [i.e, in 426 BC] finds him [recorded in the annals] as a consular tribune and also as [Mamercinus’] as master of the horse, in which capacity he fought another brilliant cavalry battle. That gives freedom for conjecture ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 10).

Livy was clearly pointing to the possibility that Cossus might have killed Tolumnius and won the spolia opima in the cavalry battle described above, when he held imperium as consular tribune and as Mamercinus’ master of horse. Livy had swiftly rejected this suggestion, but Valerius Maximus (early 1st century AD) seems to have relied on a source who did not:

-

“Next after Romulus, Cornelius Cossus consecrated spoils to the same god, [Jupiter Feretrius], when, as master of horse, he met in battle and killed the leader of the Fidenates [sic]. Great was Romulus, for he began this kind of glory at its inception. Cossus too acquired much, in that he was capable of imitating Romulus”, (‘Memorable Deeds and Sayings’, 3: 2: 3-5, translated by David Shackleton Bailey, referenced below, at p. 239).

The Virgilian commentaries are similarly confusing: John Rich (referenced below, 1996, at p. 87 and note 3) observed that, in his commentary on ‘Aeneid’, 6: 841, which mentioned Cossus among a number of Roman heroes:

Servius recorded that Cossus won the spolia opima as ‘tribunus militum’; but

‘Servius Auctus’ added the words ‘consulari potestate’.

An anonymous work that probably dates to the 4th century AD has Cossus win the spolia opima as master of horse, but names the dictator as Quinctius Cincinnatus:

“The Fidenates, old enemies of the Romans, killed the legati who had been sent to them in order to fight with more courage, without hope of forgiveness; the dictator Quinctius Cincinnatus, sent against them, Cornelius Cossus as master of horse, who killed Lars Tolumnius with his own hand. He was the second after Romulus to dedicate spolia opima to Jupiter Feretrius”, (‘De Viris Illustribus Urbis Romae” 25, my translation)

Read more:

Seubers J. and Tol G., “City, Country and Crisis in the Ager Crustuminus: Confronting Legacy Data with Resurvey Results in the Territory of ancient Crustumerium”, Paleohistoria, 57/8 (2015/6) 137-234

Bispham E., “From Asculum to Actium: The Municipalisation of Italy from the Social War to Augustus”, (2008) Oxford

Forsythe G., “Critical History of Early Rome”, (2005) Berkelely, Los Angeles and London

Shackleton Bailey D. R. (translator), “Valerius Maximus. Memorable Deeds and Sayings”, Vol.I: Books 1-5”, (2000) Harvard MA

Grandazzi A., “Foundation of Rome: Myth and History”, (1997: English edition) Ithaca and London

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume I: Book VI”, (1997) Oxford

Cornell T. C., “The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (ca. 1000-264 BC)”, (1995) London and New York

Adams Holland L., “Forerunners and Rivals of the Primitive Roman Bridge”, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 80 (1949) 281-319

Badian E., “[Review of] The Voting Districts of the Roman Republic by Lily Ross Taylor”, Journal of Roman Studies, 52: 1/2 (1962) 200-10

Ross Taylor L., “The Voting Districts of the Roman Republic: The 35 Urban and Rural Tribes”, (1960) Rome

Rackham H. (translator), “Pliny: Natural History, Volume II (Books 3-7)”, (1942) Cambridge MA

Kent R. (translator), “Varro: On the Latin Language, Volume I (Books 1-7) and Volume II (Books 8-10 and Fragments)”, (1938) Cambridge MA

Return to Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Home