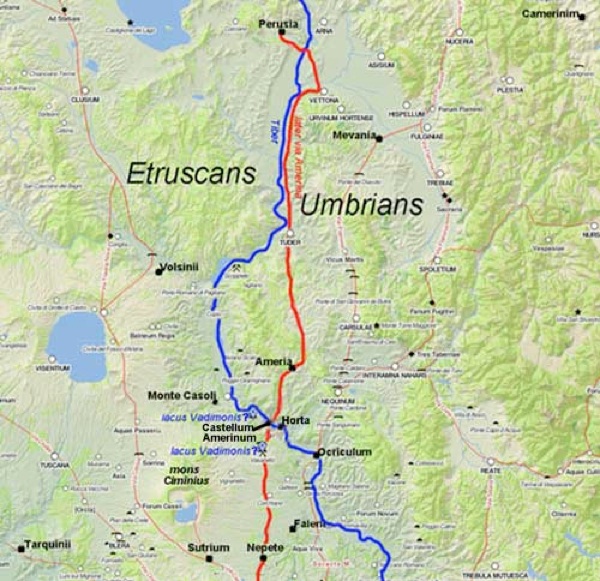

Red italics (Sabatina, Tromentina, Stellatina, Arnensis) = voting tribes established for citizen settlers in 387 BC

Red dots = Latin colonies of Sutrium and Nepete, founded in ca. 383 BC

Green dots = Etruscan cities with truces: Caere (100 years from 353 BC);

Tarquinii (40 years: 351 - 308 BC, allowing for three dictator years in this period);

Blue dot = Falerii, which was probably given a treaty in 343 BC;

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Prior Events

During their wars in Etruria in 358-1 BC, the Romans extended their territory northwards as far as the Latin colonies of Sutrium and Nepete. They also agreed:

-

✴a truce of 100 years with the Etruscan city-state of Caere in 353 BC;

-

✴a truce of 40 years with the Etruscan city-state of Tarquinii in 351 BC; and

-

✴a truce of 40 years with Faleri (the main centre of the Faliscans) in 351 BC, which was exchanged for a treaty of friendship in 343 BC.

In the later stages of the Second Samite War, in or before 311 BC, the Romans doubled the size of the consular army from one legion to two. As Timothy Cornell (referenced below, at pp. 354) observed, by this time, the Romans:

-

“... were no longer in any serious danger of defeat [by the Samnites ... and], from around 312 BC onwards, the [war in Samnium] had ceased to be the [their] principal concern.”

However, Livy noted that, in 312 BC, after almost 40 years of peace in Etruria:

-

“... the rumour of an Etruscan war sprang up. In those days, there was no other race ( apart the risings of the Gauls) whose arms were more dreaded, not only because their territory lay so near, but also because of their numbers. Accordingly, ... [the Romans prepared for war]”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 29: 1-5).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 344) suggested that the Etruscans:

-

“... chose ... to make their move [against Rome at this decisive point in the Samnite War] because they wished to preserve the balance of power in central Italy ...”

Thus, although one of the consular armies was still sent into Samnium every year during the last noe years of that war, the other was available to concentrate on the Etruscans.

Engagement at Sutrium (311 BC)

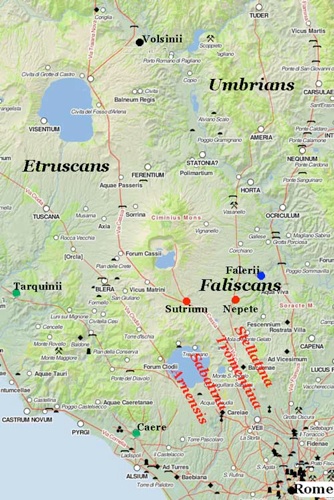

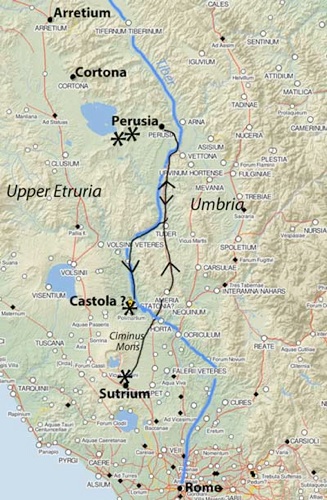

Sutrium and the Ciminian Forest in 310/9 BC

Veii fell to Rome in 396 BC and its territory was confiscated

Blue italics (Tromenina, Stellatina, Sabatina,Arnensi) = approximate location of Roman tribes of 387 BC

Blue dots (Sutrium and Nepete) = Latin colonies (386-383 BC)

Underlined = centres with treaties: Caere (100 years from 353 BC); Tarquinii (40 years from 351 BC)

Green dots = allied centres: Falerii (from 343 BC); Ocriculum (from 308 BC)

Later Roman roads ( Cassia; Amerina; Flaminia) probably indicate earlier lines of communication

Adapted from Hampus Olsson (referenced below, p. 49, Figure 1)

The consuls elected for 311 BC were Caius Junius Bubulcus Brutus (for the third time) and Quintus Aemilius Barbula. Livy, recorded that they:

-

“... divided the commands between them: [following the drawing of lots], the Samnites were assigned to Junius and the new war with Etruria was assigned to Aemilius”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 31: 1).

According to Livy:

-

“... omnes Etruriae populi (all the peoples of Etruria) except those of Arretium had ... set in train a tremendous war, beginning with the siege of Sutrium, a city in alliance with Rome and forming, as it were, the key to Etruria”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 32: 1).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 404) observed that Livy’s assertion that:

-

“... Arretium separated herself from the rest of Etruria and was at peace with with Rome in 311 BC ... appears plausible ...”

Furthermore, William Harris (referenced below, at p. 54) argued that it is unlikely that the Etruscan forces massed at Sutrium included all of the Etruscan city states except Arretium, since these states:

-

“... do not seem to have cohered sufficiently at this period to have produced such an effect.”

It seems to me that the fact that Sutrium was the centre of tension at this point throws further light on this matter: John Ward Perkins (referenced below, at p. 142) observed that:

-

“... Sutrium commanded the Sutri gap, the only practicable road up into central Etruria, between the Monti Sabatini and Monte Cimino, through country that was still densely forested.”

Thus, the likelihood is that the enemy army that assembled at Sutrium came largely from the Etruscan city-states of central Etruria (Volsinii, Clusium, Perusia, Cortona), with the notable exception of Arretium.

According to Livy, at the start of the consular year, Aemilius duly marched there at the head of an army. After what Livy characterised as a Roman victory over the besieging Etruscans:

-

“... both armies retired to their camps. Thereafter, there was nothing worth recording done at Sutrium in that year”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 32: 2).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at pp. 404-5) observed that:

-

“... there is no compelling reason to reject the Etruscan campaign of this year. Whether the fasti Triumphales were correct to record a triumph for Aemilius Barbula is more doubtful: Livy’s narrative suggests that he accomplished little, and ... it is easier to believe that a triumph was invented for this year than that it was ignored [by Livy].”

As we shall see, it is certainly the case that the Etruscan siege of Sutrium continued into the following year.

Events of 310/9 BC

Digression: Complication of a Dictator Year

This was the third of the four dictator years, so-called because:

-

✴in the fasti Capitolini:

-

•throughout 310 BC, Q. Fabius Maximus Rullianus (for the second time) and C. Marcius Rutilus served as consuls for the entire consular year of 310 BC; and

-

•throughout 309 BC, L. Papirius Cursor as a dictator for the second time and his master of horse, C. Junius Bubulcus Brutus, managed ‘public affairs’ without any consuls; and

-

✴in the fasti Triumphales, both Papirius and Fabius triumphed in 309 BC:

-

•Papirius, as dictator for the second time, over the Samnites; and

-

•Fabius, as proconsul, over the Etruscans.

In fact (discussed in my page on Dictator Years (334/3; 325/4; 310/9; and 302/1 BC)), four consul-free years (333, 324, 309 and 301 BC) were introduced in the late Republic in order to address difficulties with the Roman calendar. As far as we can tell, these fictitious years were ignored in all the later historical (as opposed to calendar-based) sources. Thus, Livy’ describes a single year in which the consuls were:

-

✴Q. Fabius Maximus Rullianus (for the second time), who campaigned in Etruria; and

-

✴C. Marcius Rutilus, who was wounded, presumed dead, in Samnium and replaced there by a dictator, L. Papirius Cursor, who appointed C. Junius Bubulcus Brutus as his master of horse.

Both Papirius and Fabius triumphed at the end of this consular year:

-

✴Papirius, over the Samnites; and

-

✴Fabius, over the Etruscans

For convenience, scholars designate this consular year as 310/9 BC.

Fabius in Etruria in the Period Before Papirius’ Dictatorship

Livy recorded, after his election as consul for the second in 310/9 BC, Fabius:

-

“... took over the campaign at Sutrium... [He] brought up replacements from Rome, and a new army came from Etruria to reinforce the enemy ”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 33: 1).

As he approached:

-

“The Etruscans, forgetting everything but their numbers, ... [impetuously launched an offensive. ... The Roman response] was too much for the Etruscans, who ... fled, headlong towards their camp. [When] the Roman cavalry ... presented themselves in front of the fugitives, [they] abandoned the attempt to reach their camp and sought the mountains; from which they made their way ... to the silva Ciminia (Ciminian Forest).. The Romans, having slain many thousand Etruscans and captured 38 standards, took possession also of the enemy's camp, with a very large booty. They then began to consider the feasibility of a pursuit”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 35: 1-8).

From this, it seems that Fabius succeeded in lifting the siege of Sutrium, but that the Etruscan army had regrouped in the safety of the nearby forest.

Ciminian Forest

Livy then digressed in order to describe the Ciminian Forest, which was to feature prominently in his subsequent account of this phase of the war:

-

“In those days, the Ciminian Forest was more inuia atque horrenda (impenetrable and terrifying) than even the forests of Germany are today, and no-one [presumably he meant no Roman], not even a trader, had visited it up to that time: hardly anyone but [Fabius] was bold enough to to enter it: the recollection of [the Roman catastrophe in 321 BC at] the Caudine Forks was still too vivid for almost everyone else”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 36: 1).

We can reasonably assume that the silva Ciminia was named for the mons Ciminus (marked on the map above). We know little about its extent in Livy’s day, and still less about its extent in the 4th century BC (although Livy clearly assumed that it had extended southwards as far as Sutrium).

Before Fabius set out into this dreadful forest in order to pursue the fleeing Etruscans, he needed reconnaissance. Fortunately (according to Livy):

-

“... one of those present, the consul's brother Marcus Fabius:

-

✴some say that it was [his half-brother], Fabius Caeso; while

-

✴others that it was Caius Claudius, a son of the same mother as the consul;

-

offered to explore and to return in a short time with definite information about everything. He had been educated at Caere [and thus] ... knew the Etruscan language well. It is said that his only companion was a slave [who was]... acquainted, like his master, with the language. ... They went dressed as shepherds and [although they were] armed with rustic weapons, ... [they received greater protection from] the fact that [the locals did not believe] that any stranger would enter the Ciminian defiles”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 36: 2-6).

However, before they returned, they had a further mission to accomplish.

Treaty with the Umbrian Camertes

Livy’s account of Fabius’ campaign of 310/9 BC, before the appointment of the dictator

Large black asterisk = battle that ended the siege of Sutrium (9: 35)

Green route = possible route to the territory of the Camertes Umbros taken by Fabius’ scouts (9:36)

I have suggested that they descended to the later route of Via Amerina and turned east at Tuder, to follow

Via Todina (see P. Camerieri, referenced below, at p. 102, Figure 10), and that they crossed the Apennines at Plestia

*? = territory possibly raided after Fabius’ descent from mons Ciminius (9:36)

Red asterisks = Livy’s alternative sites for the definitive defeat of the Etruscans (9:37)

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

According to Livy, these intrepid scouts:

-

“... are said to have penetrated as far as the ‘Camertes Umbros’ (the Umbrian people of Camertium or Camerinum), where [their leader] revealed his identity. It is said that he was introduced into the [local] senate, with whom he spoke, in the consul's name, de societate amicitiaque (of an agreement of friendship and alliance). ... He was warmly received and told to report to the Romans:

-

✴that 30 days' provisions would be waiting for the them if they came into that region; and

-

✴that the young men of the Umbrian Camertes would be armed and ready to obey their orders”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 36: 7-8).

In the map above, I have assumed that Fabius’ scouts first climbed to the top of the Ciminian Mountain (since, as we shall see, this was the route that Fabius himself was to take). I have also assumed that:

-

✴the territory of the Umbrian Camertes was around Camertium/ Camerinum (modern Camerino); and

-

✴the most convenient route from the top of the Ciminian Mountain involved:

-

•descending to the point at which the proto-Amerina crossed the Tiber;

-

•continuing along the river to Tuder; and

-

•turning east there along to the ancient route designated by Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, at p. 102, Figure 10) as the Via Todina to the Apennine pass at Plestia (modern Colfiorito), which is at the southern end of the syncline valley that leads to modern Camerino.

Livy clearly had at least two sources for this expedition, since he mentioned two conflicting records of which of Fabius’ brothers had been involved. He obviously had less than complete confidence in their accuracy in other respects, since he recorded that:

-

✴“it is said” that the younger Fabius’ only companion was a slave; and

-

✴ more importantly, that the two men “are said to have” penetrated as far as the ‘Camertes Umbros’.

Nevertheless, Frontinus, who was writing in the 1st century AD, used Livy (or one of his sources) for one of his examples of a Roman military strategy that had involved ‘Finding Out the Enemy’s Plans’:

-

“During the war with Etruria, when shrewd methods of reconnaissance were still unknown to Roman leaders, Quintus Fabius Maximus commanded his brother, Fabius Caeso, who spoke the Etruscan language fluently, to put on Etruscan dress and to penetrate into the Ciminian Forest, where our soldiers had never before ventured. He showed such discretion and energy in executing these commands that, after traversing the forest and observing that Umbros Camertes were not hostile to the Romans, he brought them into an alliance”, (‘Strategies’, 1: 2: 2).

Guy Bradley (referenced below, at p. 108) pointed out that:

-

“Camerinum, on the other side of the Apennines, is a surprisingly remote destination for a spying mission through the Ciminian Forest. ... Some [scholars (but not Bradley himself) have therefore] ... explained this passage as originating in a reference to Clusium [modern Chiusi], a city much nearer to the Ciminian Forest, which, according to Livy [‘History of Rome’, 10: 25: 11], was once called ‘Camars’.”

However, there is no doubt that the Camertes of the eastern Apennines had secured a famously ‘equal’ treaty with Rome at an early date:

-

✴According to Livy, in 205 BC:

-

“The Camertes, even though they were joined with the Romans in a treaty on equal terms (foedus aequam), nevertheless sent an armed cohort of 600 men [to fight against the Carthaginians]”, (‘History of Rome’, 28: 45: 12).

-

✴Cicero also mentioned this treaty in his speech ‘pro Balbo’ (ca. 70 ), when he referred to the fact that Caius Marius had awarded Roman citizenship to:

-

“... cohortis duas universas Camertium civitate (two whole cohorts from the city of Camertium), [despite knowing] that Camertium foedus sanctissimum atque aequissimum (the treaty that had been made with Camertium had been most solemnly ratified, and was in all respects a most equitable one)” (46, with the translation into English by Kathryn Lomas, referenced below, at p. 43).

-

✴An inscription (CIL XI 5631) from Camerino records that, in 210 AD, the Camertes thanked the Emperor Septiums Severus for confirming their foedus aequum with Rome (albeit that, at this late date, this would obviously have been a purely symbolic gesture).

Those scholars who doubt that the younger Fabius crossed the Apennines generally suggest that the Romans actually made this treaty with the Camertes in 295 BC, at the time of the Battle of Sentinum. However, Livy clearly meant the people of Camerinum in Umbria: it is surely significant that there is no surviving evidence that Etruscan Clusium or ‘ Camars’ was ever the beneficiary of a favourable treaty with Rome.

Thus, Guy Bradley (as above) and Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at pp. 459-60), among others, have argued in favour of Livy’s information that Fabius’ scouts reached the territory around modern Camerinum in 310/9 BC. The Camertes would certainly have been an attractive candidate for such a treaty, since they controlled a tract of strategically important territory, which Cicero (in his speech ‘pro Sulla’ in 63 BC) implied was of a similar extent and/or importance to that which the Romans subsequently took from the Picenes and the Gallic Senones:

-

“Where ... was Sulla? ... Was he in agro Camerti, Piceno, Gallico (the lands of the Camertes, the Picenes or the [Senonian] Gauls), which ... that frenzy [i.e. the Catilinarian conspiracy] had infected most particularly ?”, (paragraph 53).

The Camertes might well have agreed to the treaty at this point because they feared the intentions of their Gallic neighbours (as argued, for example, by William Harris, referenced below, at p. 56). However, Fabius would have been equally anxious to deter the Gauls from joining the fray as he prepared to march a Roman army into upper Etruria for the first time in its history. Thus, it is entirely possible that Fabius’ scouts set out for Camerinum via the Ciminian Forest with this objective in mind. In other words, although Livy’s tale of the exploits of the younger Fabius had obviously grown in the telling, we should probably accept Livy’s record of the agreement of an alliance between the Romans and the Umbrian Camertes at this time. As William Harris (referenced below, at p. 56) pointed out:

-

“... a plausible explanation of [a Roman treaty with Camerinum] being made in 310/9 BC can be found: Camerinum was threatened by the Senonian Gauls.”

Fabius’ March to the Top of the Mons Ciminius

By the time that Fabius received news from his scouts of:

-

✴a route through the Ciminian Forest by which he might slip past the Etruscan army; and

-

✴the understanding with the Camertes, which would have reduced the possibility that the Gallic Senones might mount an opportunistic raid;

the Etruscans seem to have regrouped and stationed sentries:

-

“... at the entrance to the pass [which was presumably one of the dreaded Ciminian defiles]”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 36: 10).

Thus, although (according to Livy) Fabius had lifted the siege of Sutrium by this time, the Etruscans still apparently controlled the route northwards through the forest. However, now that Fabius had the vital reconnaissance report, he and his army slipped away northwards under cover of darkness. By dawn on the following day:

-

“... he was on the crest of the Ciminian Mountain ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 36: 11).

I suspect that he had waited for news from his brother before moving northwards, not because he needed to know how to cross the forest (which he and his army accomplished in a few hours during the night), but rather because he wanted to know that, as marched into upper Etruria, the understanding with the Camertes was in place.

With the Etruscan army now behind him, he looked down from the mountain:

-

“ ... over the rich ploughed fields of Etruria, [which] he sent his soldiers to plunder. After the Romans had [accumulated] enormous booty, they were confronted by certain improvised bands of Etruscan peasants, called together in haste by the chief men of that country, but these peasants were so disorganised that, in seeking to regain the spoils, they nearly became spoils themselves. Having slain or driven off these men and wasted the country far and wide, the Romans returned to their camp, victorious and enriched with all manner of supplies”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 36: 11-13).

Apparently, when Fabius reached this camp, he:

-

“... found five legates, with two tribunes of the plebs, who had come to order [him], in the name of the Senate, not to cross the Ciminian Forest. Rejoicing that they had come too late to be able to hinder the war, they returned to Rome with tidings of victory”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 36: 14).

I will return to the significance of this passage below.

According to Livy:

-

“This expedition of Fabius, instead of putting an end to the war, only gave it a wider range. For the district lying about the base of [the mountain] had felt the devastation, and this had aroused not only Etruria to resentment but also the neighbouring parts of Umbria”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 37: 1).

This is the first time that Livy recorded any Umbrians in conflict with Rome: on the map above, I suggest that:

-

✴the Umbrian territory that Fabius might have raided from the Ciminian Mountain included that along the route towards Tuder, which the younger Fabius had probably already explored; and

-

✴the Etruscan territory involved that of Tarquinii, since the treaty that they had agreed with the Romans was no longer in force.

Fabius’ Victory Over the Etruscans

Livy gave two possible locations for the battle that followed this raid, which I have marked with red asterisks on the map at the top of the page:

-

✴In Livy’s preferred version, after Fabius returned to Sutrium:

-

“... a [new Etruscan army arrived there] that was larger than any [that the Etruscans] had raised before. Not only did they move their camp forward out of the woods but, in their eagerness for combat, they even came down into the plain ... in battle formation ... [and] advanced up to the rampart [of the Roman camp]. When they saw that even the Roman sentries had retired within the works, they began shouting to their generals that ... [they should immediately] attack the enemy's stockade. ... [However, Fabius chose not to give battle, but rather decided to allow his men to eat and to rest, presumably because they had only recently arrived.] Then, when the signal was given a little before dawn,... the Romans ... fell upon their enemies, who were lying all about the field. [This surprise Roman attack put the enemy to flight, and their] camp, being situated in the plain, was captured the same day. ... On that day, 60,000 [Etruscan combatants] were killed or captured”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 37: 2-11).

-

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 480) noted that this figure of 60,000:

-

“... is a much larger figure than that usually reported by Livy [after Roman victories].”

-

✴Livy acknowledged that :

-

“Some historians relate that this famous battle was fought on the other side of the Ciminian Forest, near Perusia, and that Rome was in a panic lest the army should be surrounded and cut off in that dangerous defile by the Etruscans and Umbrians rising up on every hand”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 37: 11).

Result of Fabius’ ‘Famous Victory’

Livy concluded that, whether this famous victory was won to the north or to the south of the Ciminian Forest:

-

“... the Romans were the victors. And so, ambassadors from Perusia and Cortona and Arretium, which, at that time, were effectively capita Etruriae populorum (the chief cities of the Etruscan people), came to Rome to sue for peace and a foedus (treaty). They obtained truces for 30 years”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 37: 12).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, a2005, at p. 415) suggested that:

-

“If this notice is sound, ... it may imply that, [although Arretium did not fight in 311 BC, as Livy claimed, it joined the Etruscan reinforcements of 310/9 BC. Alternatively], Roman successes in Etruria may have encouraged [Arretium] to formalise an already friendly link with Rome.”

I return to this point below.

Probable Location of Fabius’ Famous Victory

Livy did not deny that the ‘alternative’ sources for this famous battle were correct when they claimed that there had been disquiet at Rome about Fabius’ crossing of the Ciminian Forest, but he related it to Fabius’ earlier surprise raid on upper Etruria from the summit of the Ciminian Mountain, after which (as noted above) he returned safely to his camp at Sutrium, only to find:

-

“... five legates, with two tribunes of the plebs, who had come to order [him], in the name of the Senate, not to cross the Ciminian Forest. Rejoicing that they had come too late to be able to hinder the war, they returned to Rome with tidings of victory”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 36: 14).

There are at least two problems with this ‘preferred’ account:

-

✴It seems odd (at least to me) that an encounter with what Livy described as:

-

“... improvised bands of Etruscan peasants”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 36: 12);

-

would now be characterised as a war (bellum): Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 475):

-

•pointed out that:

-

“... one might have expected [Livy] to use the word expeditionem [expedition or campaign]”;

-

•and noted that this had been Livy’s earlier usage:

-

“Hac expeditione consulis motum latius erat quam profligatum bellum”

-

“This expedition of the consul, instead of putting an end to the war, only gave it a wider range, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 37: 1)

-

✴Furthermore, it seems odd that the legates regarded as a victory an expedition that had actually escalated the war and brought more men, both Etruscan and Umbrian, to Sutrium.

It is surely more likely that the legation arrived in Fabius’ camp after Fabius’ famous victory. In other words, if this record of the legation from Rome is correct, then Livy probably placed it too early in his account: it belonged more naturally after the ‘famous battle’, which was therefore fought (as Livy’s alternative sources suggested) on the far side of the Ciminian Forest.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 33) made the case for the ‘alternative’ hypothesis from a different perspective: he argued that Livy’s preferred version of events contained a number of internal contradictions:

-

“The concentration of all these events in the restricted area between the Ciminian Mountain and the Tiber [see the map above] is suspect. ... [It would, for example, have rendered pointless] the sending of emissaries to the Camertes, [whose territory] was so far from the theatre of war. [It also seems odd that]:

-

✴a war that had been conducted in southern Etruria should be followed by the surrender of three northern centres, Perusia, Cortona and Arretium, particularly since Livy explicitly affirmed that the last of these had not taken part in the siege of Sutrium; and

-

✴... the devastation of the territory immediately below the Ciminian Mountain had caused the uprising of the nearby Umbrians, [since their territory was on the other side of the] Tiber” (my translation).

It seems to me that the case for locating Fabius’ famous victory at Perusia is overwhelming, particular since it would account for otherwise strange fate of Arretium, which might well have joined the Perusia and Cortona in resisting the Romans only after Fabius had crossed into central Etruria.

Parallel Account of Diodorus Siculus

Approximate route for Fabius’ campaign of 310/9 BC, following Diodorus

I have shown here the direct route from Sutrium, along the later route of Via Amerina to Perusia

Asterisks = sites of the four battles described by Diodorus (the first of which he attributed to both consuls)

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 454 pointed out, Diodorus Siculus recorded that the truces with Arretium Cortona and Perusia followed a victory at Perusia rather than one at Sutrium:

-

✴First, as the Etruscans moved to reinforce the army besieging Sutrium, Fabius outflanked them by slipping away to the north:

-

“While the Etruscans were gathering in great numbers against Sutrium, Fabius marched without their knowledge through the country of their [Umbrian] neighbours and into upper Etruria, which had not been plundered for a long time. Falling upon it unexpectedly, he ravaged a large part of the country; and, in a victory over those of the inhabitants who came against him, he killed many of them and took no small number of them alive as prisoners”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 35: 2-3).

-

On the map above, I have assumed that:

-

•Fabius marched along the line of the later Via Amerina, through Umbrian Ameria and Tuder, before crossing the Tiber into upper Etruria (although, as we shall see, Livy had him first slip away from Sutrium to the top of the mons Ciminius); and

-

•Fabius’ first battle in upper Etruria (like his second) took place near Perusia (although Diodorus Diodorus was unspecific here).

-

✴Fabius then fought a much more important battle near Perusia:

-

“Thereafter, defeating the Etruscans in a second battle near the place called Perusia and destroying many of them, he overawed the nation, since he was the first of the Romans to have invaded that region with an army. He also made truces with the peoples of: Arretium and [Cortona]; and likewise with those of Perusia”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 35: 4-5).

-

✴He then marched south and:

-

“... taking by siege the city called Castola, he forced the Etruscans to raise the siege of Sutrium”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 35: 5).

-

This is the only surviving reference to the existence of the Etruscan centre of Castola. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 457) was inclined to accept Diodorus account precisely because, in his view:

-

“...a reference to so obscure a site is most unlikely to have been invented.”

-

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at: p. 36, note 37; and p. 34, Figure 1) also argued that Fabius might well have engaged with an Etruscan army that was still besieging Sutrium as he marched back to Rome. He suggested that ‘Castola’ might have been the ancient fortified site at Monte Casoli, near modern Bomarzo, marked on the map above. If so, then the most convenient route from Perusia would have been back along Via Amerina to the vicinity of Tuder and then along the Tiber valley (as marked on the map above).

As discussed below, the engagement at ‘Castola’ might have followed the appointment of Papirius as dictator, which Diodorus did not record. I will therefore return to it in the section on the period of Papirius’ dictatorship.

This alternative version of events meets at least two of the objections raised by Simone Sisani in relation to Livy’s preferred version (above):

-

✴Fabius might well have arranged for an understanding with the Camertes before he crossed the Tiber into upper Etruria, not least because it would have reduced the risk that the Gallic Senones would attempt to take advantage; and

-

✴the shock of this first appearance of a hostile Roman army in upper Etruria, followed by a significant Roman victory, might well have prompted Perusia, Cortona and Arretium to sue for peace.

Fabius in Etruria in the Period Before Papirius’ Dictatorship: Conclusions

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at pp. 455) demonstrated that much of the accounts of Diodorus and Livy can be reconciled by assuming that Fabius:

-

✴marched to relieve Sutrium and defeated the Etruscans there;

-

✴crossed the Ciminian Forest, as reported only by Livy;

-

✴defeated a peasant army in upper Etruria;

-

✴defeated a significant Etruscan army near Perusia; and then

-

✴agreed truces with Arretium, Cortona and Perusia. (Note that Livy is the only surviving source for the valuable information that these were truces for 30 years.)

He also noted that we might reasonably accept:

-

✴the mission of Fabius‘ brother to the Umbrian Camertes (mentioned by at least two of Livy’s sources);

-

✴an embassy from Rome to Fabius (which, on this scenario, would have reached him after his victory near Perusia); and

-

✴contact with the Umbrians (presumably in the context of the defeat of a peasant army in upper Etruria.

Appointment of L. Papirius Cursor as Dictator

Marcius’ Indisposition

According to Livy, when news emerged that Fabius had crossed the Ciminian Forest (but before his famous victory at Perusia) the Samnites, who expected that he would be defeated:

-

“... hastened to bring all their strength to bear upon crushing [the other consul], C. Marcius ... [He] met them [at an unspecified location in Samnium], and the battle was fiercely contested on both sides, but without a decision being reached. Yet, although it was doubtful which side had suffered most, the report gained ground that the Romans had been worsted ... and, most conspicuous of their misfortunes, Marcius himself was wounded. These reverses ... were further exaggerated in the telling, and the Senate... determined on the appointment of a dictator”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38: 8-10).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at pp. 460) pointed out that Marcius probably did suffer a reverse at this time, since:

-

“... the annalistic tradition is unlikely to have invented a Roman defeat ...”

Senatorial Deputation to Fabius

According to Livy, once the Senate had decided to appoint a dictator to replace Marcius in Samnium:

-

“Nobody could doubt that Papirius Cursor, who was regarded as the foremost soldier of his time, would be designated”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38: 10).

Formally, the appointment had to be made by one of the consuls and, since Marcius was missing in action, it had to be made by Fabius. Since he:

-

“... had a private grudge against Papirius, ... the Senate decided to send a deputation of former consuls to him ... [in order to] induce him to forget those quarrels in the national interest. The ambassadors [duly] went to Fabius and delivered the resolution of the Senate, with a discourse that suited their instructions”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38: 10-13).

As we have seen above, when Fabius had returned to his camp, probably after his famous victory near Perusia, he:

-

“... found five legates, with two tribunes of the plebs, who had come to order [him], in the name of the Senate, not to cross the Ciminian Forest. Rejoicing that they had come too late to be able to hinder the war, they returned to Rome with tidings of victory”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 36: 14).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 456) argued that:

-

“... it is most unlikely that, in the course of one campaign, the Senate sent two embassies to a consul ...

He also argued (at p. 457) that

-

“ the important points [from his previous analysis] are that:

-

✴much of Livy’s Etruscan narrative after 37: 12 duplicates what he recounts between 35: 1 and 37: 12; and

-

✴all of it is likely to be fictional.”

In other words, the likelihood is that both of these records probably refer to a single senatorial deputation. If so, then:

-

✴it would have been sent to warn him not to cross the Ciminian Forest and to order him to appoint Papirius as dictator; and

-

✴it would have reached him on his return to his camp immediately after his famous victory at Perusia.

Fabius’ initial response to the envoys’ request were unsettling:

-

“Fabius, his eyes fixed on the ground, retired without a word ... Then, in the silence of the night, as custom dictates, he appointed Papirius dictator. When the envoys thanked him ... , he continued obstinately silent, ... so that it was clearly seen what agony his great heart was suppressing. Papirius named Caius Junius Bubulcus [the consul of 311 BC -see above], as his master of the horse”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 38: 13-15).

Cassius Dio, gave a shorter account of these events:

-

“The men of the city put forward Papirius as dictator and, fearing that Fabius might be unwilling to name him on account of [their mutual hostility], they sent to him and begged him to place the national interest before his private grudge. Initially, he gave the envoys no response, but when night had come (according to ancient custom it was absolutely necessary that the dictator be appointed at night), he named Papirius, and by this act gained the greatest renown. (‘Roman History’, 8: 36: 26).

It seems likely that these accounts had a common source, albeit that Livy accepted or invented some elaborations relating to Fabius’ strange behaviour. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 461 and note 1) observed that, although some scholars reject this dictatorship:

-

“In this period, the appointment of a dictator was a regular Roman response to military difficulty, and there is therefore no compelling reason to doubt [Papirius’ dictatorship], even if Livy’s account of panic at Rome after the defeat of Marcius derives only from his own imagination or that of his sources.”

Manuscript Corruption at 9: 39: 4-5

Livy now switched to an account of Papirius’ first engagement with the Samnites at Longula (a now-unknown location that was probably in Samnium). His account of this engagement ended abruptly (at least in the surviving manuscripts):

-

“... while the two armies stood armed and ready for the conflict, ... night overtook them. [They retired to their respective camps] ... and remained [there] for some days: they did not doubt their own strength, but neither did they underestimate that of the enemy”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 39: 3-4).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 499) pointed out that:

-

“It is quite likely that [this] was not originally the end of Livy’s description of this part of Papirius’ campaign, but was [instead] leading up to an account of a battle that was about to take place.”

He hardened this conclusion at p. 500:

-

“The arguments in favour of a lacuna after [this passage] ... are ... overwhelming.”

The surviving manuscripts therefore continue with a non sequitur:

-

“Nam et cum Umbrorum exercitu acie depugnatum est; fusi tamen magis quam caesi hostes, quia coeptam acriter non tolerarunt pugnam; et ad Vadimonis lacum Etrusci lege sacrata coacto exercitu ...”

-

“For, a battle was fought with the Umbrians: they were unable to maintain the fury with which they began it, and they fled before they had suffered any great loss. And, at Lake Vadimo, the Etruscans had concentrated an army raised under a lex sacrata ...” (‘‘History of Rome’, 9: 39: 4-5, my translation).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 497) pointed out, the transcribers responsible for some of the surviving manuscripts placed obeli († ... †) around the words †nam et cum Umbrorum ... et ad Vadimonis lacum† in order to flag that this passage seemed to them to be to be corrupt. Oakley

-

✴observed that:

-

“... this is one of the most desperate textual cruces [puzzling or difficult passages] in Livy’s first [ten books] ...”; and

-

✴argued that Charles Walters:

-

“... was right to obelise[this] passage [in his edition of the Latin text (referenced below, at p. 283)].”

He also noted that the transcribers of a small number of other surviving manuscripts had attempted to ‘correct’ them in transcription:

-

✴one of them (M) had inserted ‘et rurae’ (presumably to suggest ‘in Etruria’) as an introductory supplement before ‘nam’; and

-

✴two of them (Pc and U) had inserted ‘interea res in Etruria gestae‘ (meanwhile, achievements in Etruria) before ‘et ad Vadimonis lacum’: Oakley commented (at p. 498) that:

-

“... looks like a desperate attempt to restore sense to a corrupt text.”

Published translations into English often omit this passage completely and insert a linking ‘meanwhile’: for example:

-

✴Benjamin Foster (referenced below, at p. 317) translated the relevant passages as:

-

“For some time... [the armies at Longula] remained quietly in the camps that they had established near each other, neither lacking confidence in themselves nor yet making light of their adversaries. Meanwhile, the Etruscans, employing a lex sacrata ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 39: 4-5).

-

He addressed the manuscript problem at p. 316, note 1. Thus, in the translation, the Umbrian engagement is omitted completely, along with the reference to Lake Vadimo.

-

✴John Yardley (referenced below, at p. 213) did likewise, albeit that he flagged the existence of the obelised passage as † ...† and reproduced it in Latin in a note at p. 289.

However, William Roberts (whose older translation is available on-line) included the obelised passage and the insertion based on that of Pc and U (which I have put in italics):

-

“Meantime, the Romans were meeting with success in Etruria: for, in an engagement with the Umbrians, the enemy were unable to keep up the fight with the spirit with which they began it, and, without any great loss, were completely routed. An engagement also took place at Lake Vadimo, where the Etruscans had concentrated an army raised under a lex sacrata ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 39: 4-5).

Robert Ogilvie (referenced below, at p. 167) also proposed this solution, although Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at pp. 498-9) addressed the problems with it at some length.

An Engagement with the Umbrians ?

As discussed above, Livy’s entire account of this engagement is contained within the obelised passage. If it is in the correct place in Livy’s narrative, then it took place after:

-

✴Fabius’ famous victory near Perusia; and

-

✴the appointment of Papirius as dictator; and

-

✴immediately before an engagement at Lake Vadimo with an Etruscan army that had been raised under a lex sacrata (discussed below).

As its it stands, Livy’s narrative does not reveal:

-

✴who ‘the Umbrians’ were (or even whether they were recognisably an army, as opposed to an unorganised band of some sort);

-

✴where this rout took place; or

-

✴who commanded the Roman army that effected it.

Furthermore, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at pp. 498-9) identified two other problems with this passage:

-

✴In his paragraph (a), he noted that it clearly contradicts a later passage in which Livy claimed that:

-

“The tranquillity that ... obtained in Etruria [in 308 BC] was disturbed by a sudden revolt of the Umbrians, [who had, up to that point], escaped all the distress of war, except that a [Roman] army had [previously] passed through their territory”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 8).

-

✴In his paragraph (c), he noted that the battle itself:

-

“... is recounted with extraordinary brevity: this might be expected at the end of the narrative of a year or of a long campaign, but it is something of a surprise in the middle of the account of the campaigns of 310/9 BC. Sandwiched between ... a campaign against the Samnites and then one against the Etruscans, the Umbrians make a most odd appearance.”

As we have seen, some scholars resolve these problems by simply omitting this passage. However, as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 500) observed:

-

“... it is hard to see why this insertion would be made .”

He pointed out that William Anderson (referenced below, at pp. 101-3) argued that the obelised passage should be inserted after 9: 39: 11. However, as he also pointed out, the account at 9:41 of a major engagement between the Romans and the Umbrians in 308 BC is essentially complete as it stands. In fact, it seems to me that 9: 39: 4 represents an excellent précis of it:

-

✴In 9: 39: 4, a now-unnamed Roman commander engaged with:

-

“... the Umbrians ... , [who] were unable to keep up the fight with the spirit with which they began it, and, [without having suffered] any great loss, were completely routed.”

-

✴In the engagement described in 9: 41, which took place against an organised pan-Umbrian army mustered at Mevania in 308 BC:

-

•an Umbrian army began the engagement by threatening to:

-

“... [leave the consul] Decius in their rear and [march]... on Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 9); but

-

•on realising that P. Decius Mus had outflanked them and that the other consul (Fabius again) had arrived to engage with them, the Umbrians quickly lost heart. Thus, in the battle that followed:

-

“More [Umbrians] were captured than were killed, and only one cry was heard throughout their ranks: ‘Lay down your arms!’ So, on the field of battle, the prime authors of the war surrendered”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 19)

In my view, the most obvious reason for this is that these descriptions relate to the same battle, but that Livy had failed to recognise this because his sources for it contained conflicting information on (inter alia):

-

✴the year in which it was fought (310/9 BC or 308 BC ??);

-

✴the importance of this engagement (a minor skirmish in Etruria or the defeat of an army that had been assembled at Mevania and represented a credible threat to Rome itself ??).

-

✴the place at which it was fought (near Etruria or at Mevania ??);

-

✴the character of the enemy (an unorganised rabble or a large and properly mustered army); and

-

✴the identity of the victorious Roman commander (Fabius, in his second consulship of in 310/9 BC; Papirius, in his second term as dictator in 310/9 BC; Fabius, in his third consulship of 308 BC; or Decius, the other consul of 308 BC ??).

I also think that one of Livy’s sources:

-

✴ attributed this battle (and the one at Lake Vadimo that followed it) to Papirius; and

-

✴placed it in the fictitious, consul-free year between Fabius’ second and third consulships.

Engagement with the Etruscans at Lake Vadimo/ Castola ?

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

According to the surviving manuscripts:

-

“†... at Lake Vadimo†, the Etruscans, using a lex sacrata (sacred law), had raised an army cum vir virum legisset (in which each man had chosen another). This army fought with more men and with greater courage than ever before. So savage was the feeling on both sides that ... [the outcome] long hung in the balance. [It seemed to the Romans that they were engaging] with some new, unknown people, rather than with the Etruscans (whom they had so often defeated). ... [However, an unexpected Roman tactic - see below] threw the Etruscan standards into confusion ... and [the Romans] at last broke through their ranks. Their determined resistance was now overcome and ... they soon took flight. That day, for the first time, broke the power of the Etruscans after their long-continued and abundant prosperity. The main strength of their army was left [dead] on the field, and their camp was taken and plundered”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 39: 5-11).

Lake Vadimo

As Simon Stoddart and Caroline Malone (referenced below, at p. 3) pointed out:

-

“Most ancient lakes [in Umbria], such as the ... Vadimone lake, near [Ameria, modern] Amelia ... , have now disappeared.”

The only useful indication in our surviving sources of its location and appearance comes in a letter that Pliny the Younger wrote in the late 1st century AD:

-

“My [father-in-law, Calpurnius Fabatus] desired that I should look over Amerina praedia sua (his estate near Ameria). As I was walking over his grounds, I was shown a lake that lies below them, called Vadimonis, about which several very extraordinary things are told. ... It is perfectly circular in form, ... just as if it had been ... cut out by the hand of art. The water is of a clear sky-blue, though with somewhat of a greenish tinge; its smell is sulphurous, ... Though it is of only moderate extent, the winds have a great effect upon it, throwing it into violent agitation. No vessels are allowed to sail here, as its waters are held sacred; but several floating islands swim about it ... This lake empties itself into a river, which, after running a little way, sinks underground, and, if anything is thrown in, it brings it up again where the stream emerges”, (Letter 93: to Gallus).

In his book about his travels in Etruria in the 1840s, the redoubtable George Dennis (referenced below) believed that he had found the remnants of this lake:

-

“If you follow the banks of the Tiber [westwards] for about 4 miles [from Horta, modern] Orte, you will reach the ‘Laghetto/ Lagherello/ Lago di Bassano’, which [takes its name from] a village in the neighbourhood. [This was] the Vadimonian Lake of antiquity ...”

This site is on a bend in the Tiber, some 4 km northeast of modern Bassano in Teverina, where a sink hole of some 40 meters in diameter survives. However, Ardelio Loppi (referenced below) pointed out, Pliny would not have described the Tiber as simply ‘a river’. He suggested that it was more probably at Poggio del Lago, near modern Vasanello (or Bassanello), some 10 km to the south of Castellum Amerinum, where the later via Amerina crossed the Tiber. I have marked both locations on the map above. Thus, the general location of the ancient lake is clear enough: it was about:

-

✴40 km north of Roman territory (which ended at the Latin colonies of Sutrium and Nepete);

-

✴25 km north of Falerii, which was allied to Rome;

-

✴50 km southeast of the Etruscan city-state of Volsinii; and

-

✴70 km east of the Etruscan city-state of Tarquinii.

Some scholars reject the existence of an engagement of any kind between the Romans and the Etruscans at Lake Vadimo in 310/9 BC: as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 498, paragraph (b)) observed:

-

“It is quite certain that there was a [Roman victory over a coalition of Gauls and Etruscans] at this lake in 283 BC, but [Livy is our only surviving source for] a previous battle against the Etruscans at this site in 310/9 BC.”

In note 3, he cited (inter alia) William Harris (referenced below, at p. 56), who argued that the earlier engagement is:

-

“... generally regarded as a doublet of ... [that of] 283 BC, which is described by Polybius [see below]. The site of the battle is so specific that it is [indeed] necessary to reject one or the other and, in spite of the difficulties [with the surviving sources for the battle] of 283 BC, it clearly belongs to that year.”

Oakley (as above) similarly cautioned that:

-

“... although the notion of [Livy’s putative battle of 310/9 BC] is not ... absolutely incredible, the unreliability of Livy’s general account of events in this year (and, in particular, of 9: 39: 4) means that one should be very cautious indeed about accepting it.”

However, it seems to me that, pace William Harris, it is entirely possible that the Romans engaged with an Etruscan army at Lake Vadimo on more that one occasion: as George Dennis (referenced below) observed:

-

“Whoever visits the [likely site of Lake Vadimo] will comprehend how it was that decisive battles were fought upon its shores. The valley here forms the natural pass into the inner or central plain of Etruria. It ... [occupies] a low, level tract, about a mile wide, hemmed in between the heights [of the mons Ciminius] and the Tiber ... ; ... these heights ... are, even now, densely covered with wood, as no doubt they were in ancient times, this being part of the celebrated Ciminian forest.”

Furthermore, as we have seen, Lake Vadimo was only 40 km north of the Latin colonies of Sutrium and Nepete, which defended the road to Rome. In other words, it seems to me that there is no basis for dismissing Livy’s account of a major battle against the Etruscans at Lake Vadimo in 310/9 BC simply on the basis of its location.

Did the Romans Win Two Major Battles Against the Etruscans in 310/9 BC ?

We might nevertheless wonder whether another significant Roman victory over the Etruscans really did feature among what Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at pp. 35-6), for example, described as:

-

“... the events of the [apparently] interminable 310/9 BC” (my translation).

After all, according to Livy, Fabius had already:

-

✴defeated the largest army that the Etruscans and Umbrians had ever sent against the Romans; and

-

✴imposed 30-year truces on Arretium, Cortona and Perusia, three of the leading city-states of upper Etruria.

Although Livy thought that this ‘famous battle’ had taken place near Sutrium, he acknowledged that some historians located it near Perusia. Diodorus Siculus, who also recorded this victory and the truces with Arretium, Cortona and Perusia that followed it, also placed it at Perusia. However, Livy and Diodorus gave what, at first sight, seem to be different accounts of what happened next in Etruria:

-

✴As we have seen, Livy recorded that a now-unnamed Roman commander defeated an even larger Etruscan army at Lake Vadimo, and that the power of the Etruscans was broken for the first time in this second battle.

-

✴According to Diodorus, Fabius marched south from Perusia and:

-

“... taking by siege the city called Castola, ... forced the Etruscans to raise the siege of Sutrium”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 35: 5).

Modern scholars have taken different positions on whether either or both of these records should be accepted. For example:

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at pp. 35-6) argued that:

-

“The last clash [in Etruria in 310/9 BC], which must have seen the Etruscans and Umbrians deployed against the Romans, took place on the route of Fabius’ return towards Sutrium:

-

•near the lacus Vadimonis [Livy]; and

-

•not far from the possible location of the otherwise unknown city called Castola, which Fabius had seized [Diodorus].

-

It is here that the Romans defeated the troops that were still besieging Sutrium, thereby liberating that city and earning Fabius a triumph” (my translation).

-

He:

-

•suggested (at p. 36, note 37) that ‘Castola’ might have been located at the ancient fortified site that has been excavated at Monte Casoli, near modern Bomarzo, some 15 km west of Lake Vadimo, and

-

•marked battles at each of these locations in his reconstruction of Fabius’ route from Perusia towards Sutrium (in Figure 1, at p. 34).

-

✴Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 456) considered whether the victory at Lake Vadimo:

-

“... is a doublet of that recorded at [near Perusia, mentioned above ... This hypothesis] cannot be proved beyond doubt, but it] involves no historical difficulties and allows a coherent reconstruction of events.”

-

He elaborated (at p. 498, note 3):

-

“If the reference to Vadimo really does belong in the text, then either Livy or his ... sources may have either accidentally produced a doublet or deliberately invented another [campaign here].”

-

However, Oakley (at p. 457), like Sisani, was inclined to accept Diodorus’ account, arguing that:

-

“...a reference to so obscure a site is most unlikely to have been invented.”

We can take this discussion forward by considering another observation by Stephen Oakley: he pointed out (at p. 499, paragraph (g)) that, in the original Latin, the link between 39: 4 and 39: 5 is structured as follows:

-

“nam et cum Umbrorum ... et ad Vadimonis lacum ...”.

He observed that:

-

“One does not expect a trivial campaign against the Umbrians to be linked ... [by the stylistic device] ‘et ...et ...’ with the opening of [the great battle against the Etruscans]” (my changed order of clauses).

He suggested (at p. 500) that there might originally have been text after ‘ad Vadimonis lacum’ that has been lost. In other words, the ‘trivial engagement with the Umbrians’ might originally have been followed by now-lost text that:

-

✴described a relatively trivial engagement with the Etruscans at the lacus Vadimonis; and then

-

✴introduced the battle in which the Romans broke the power of the Etruscans for the first time.

It seems to me that a more economical explanation for this grammatical construct would be that Livy had subsequently embellished what had been a relatively unimportant engagement with the Etruscans in an earlier version of his narrative. Furthermore, Diodorus’ record of Fabius success at Castola would be an obvious candidate for this relatively trivial engagement with the Etruscans, and it is entirely possible (as Sisani suggested) that this Etruscan city was near the lacus Vadimonis. In other words, it is at least possible that, at 9: 39: 5-11, Livy provided an embellished account of the Roman engagement at Castola (which Diodorus attributed, not necessarily correctly, to Fabius).

Which Etruscans Were Defeated at Lake Vadimo/ Castola ?

Livy gave no indication of which Etruscan city-states had sent men to the muster at Lake Vadimo. However, we might make some deductions:

-

✴Livy did not suggest that any of Perusia, Cortona and. Arretium had violated its recently-agreed 30-year truce.

-

✴Furthermore, the 40-year truce that the Romans had agreed with Tarquinii in 351 BC was not due to expire until 308 BC (allowing for 3 dictator years in the intervening period),. Since (as we shall see) it was duly renewed for another 40 years at that point., it seems unlikely that Tarquinii had played a significant role in the hostilities of 310/9 BC.

It seems to me that the most obvious candidate would be Volsinii, which might well have assumed responsibility for the continuing the siege of Sutrium after Arretium, Cortona and Perusia submitted to Rome:

-

✴both Castola and Lake Vadimo might well have been in its territory; and

-

✴(as we shall see) it again suffered the hostile attention of the Romans in 308 BC.

This hypothesis does not exclude the possibility that Etruscans from other city-states had been drawn to Castola from the siege of Sutrium. However, it seems likely that any Etruscans from cities that had truces with Rome participated in the hostilities without the overt sanction of their city states.

Which Roman Commander Secured this Putative Second Victory ?

As we have seen, according to Livy, the Roman commander who was responsible for this victory:

-

“... broke the power of the Etruscans for the first time ... The main strength of their army was left [dead] on the field ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 39: 5-11).

In view of the glory that would have attended such an achievement, it is extremely surprising that, at least in the surviving manuscripts, Livy did not identify him. In my view, this omission is unlikely to be simply the result of missing text: Livy’s account of the battle is written as if the men on both sides fought spontaneously, without needing direction from above:

-

“So savage was the feeling on both sides that, without discharging a single missile, the soldiers began the fight with swords from the start. ... There was not the slightest sign of yielding anywhere: as the men in the first line fell, those in the second took their places to defend the standards. At length, the last reserves had to be brought up, and matters had come to such an extremity of exhaustion and danger that the Roman cavalry dismounted and ... made their way ... to the front ranks of the infantry. They appeared [there] like a fresh army amongst the exhausted combatants, and immediately threw the Etruscan standards into confusion. The [Roman infantry], worn out as they were, nevertheless followed up the cavalry attack, and at last broke through the Etruscan ranks ... They soon took to flight ... , [leaving] the main strength of their army [dead] on the field, and their camp was taken and plundered”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 39: 6-10).

This conundrum had apparently occurred to the scribes responsible for one of the surviving surviving manuscripts ((Fc): Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 499, paragraph (e)) noted that he inserted the phrase ‘interim ab fabio consule in Etruria res feliciter gestae’ (Meanwhile, the consul Fabius was meeting with success in Etruria) before ‘et ad Vadimonis lacum’. Oakley agreed that:

-

“One would rather have expected Fabius to have been in charge on the Etruscan front; but he is nowhere mentioned ... ”.

Instead, as Oakley pointed out:

-

“Scholars tend to assume that Papirius was in command ...”

However, in Oakley’s view, this hypothesis:

-

“... is absurd, [since it has Papirius] moving from [Longula] to Lake Vadimo and then back to Samnium [where he triumphed over the Samnites].”

He added (at paragraph (f)) that, even if one accepts this hypothesis:

-

“... there remains the difficulty that there ought to be some [indication] of how he moved from Longula to Lake Vadimo.”

It is possible that Livy simply had no information as to the identity of this victorious commander, although it is hard to see how it could have been anyone other that Fabius or Papirius. It seems to me that Livy’s silence on the matter arose from the fact that he was struggling to reconcile discordant sources:

-

✴those that favoured Papirius might well have credited him with an excursion from Longula to Lake Vadimo and back to Samnium during his putative dictator year (however absurd this might have been); while.

-

✴those that favoured Fabius might well have :

-

•named him as the victorious commander and described the battle as a trivial mopping-up operation; or

-

•denied that it happened at all.

There is, in fact, another indication that much of Livy’s account came from one or more sources that favoured Papirius: as we have seen, the unnamed commander had defeated an Etruscan army that had been:

-

“... raised ... cum vir virum legisset (by each man had chosen another)”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 39: 5).

As I discuss in my page Second Samnite War III (311 - 308 BC), this detail had probably been taken from an account of the more reliably authentic victory that Papirius’ homonymous son had secured against the Samnites in 293 BC.

Fabius’ Decisive Victory over the Etruscans at Perusia (?)

Having described Papirius’ triumph over the Samnites, Livy immediately turned to a description of what he characterised as Fabius’ decisive victory over the Etruscans:

-

“In the same year, the consul Fabius fought a battle with the remnants of the Etruscan forces near Perusia, which, together with other cities, had broken the truce. [He] gained an easy and decisive victory. After the battle, he marched up to the walls of the city and would have taken the city itself had not ambassadors come out and surrendered the place. [He] placed a garrison in Perusia, and ... sent on before him to the Senate in Rome the Etruscan deputations that had come to him amicitiam petentibus (seeking friendship) ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 40: 18-20).

There are a number of problems with this account. For example as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 455) pointed out, even though Livy claimed that Perusia and other cities had broken the truce, his report:

-

“... follows oddly on [the 30 year truces] agreed earlier in the year with Arretium, Cortona and Perusia.”

It also seems odd that Livy did not record the Senate’s answer to the Etruscan deputations that had come to Fabius seeking friendship. The Romans’ apparently easy victory over Perusia seems equally odd: as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 455) observed:

-

“This is [Livy’s] only report of the surrender of a major Etruscan settlement in the war of 311-308 BC ...[and] it is doubtful whether ... the Romans had an army strong enough to capture or force the surrender of any of the major Etruscan cities [at this time].”

He concluded that:

-

“One cannot prove finally that this section is a doublet ..., but this does seem extremely probable. ”

Simoni Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 35) agreed, and suggested that the memory of Livy’s second version of Fabius victory of 310 BC, which located it to the north of the Ciminian Forest, near Perusia:

-

“... must have been so strong as to push Livy to include it [again] at the end of the interminable 310 BC, thereby duplicating the facts of the engagement that, shortly before, had taken place near the Ciminian Forest and had led to the truces with the centres of northern Etruria” (my translation).

However, in my view, as I discuss further below, Livy inserted this doublet in order to reconcile his account with others that he found in sources that accepted the fictitious dictator year of 309 BC.

Fabius’ Triumph

Livy ended his account of this consular year by recording that, having garrisoned Perusia, and sent on the Etruscan deputations ahead of him to negotiate with the Senate:

-

“... Fabius was borne in triumph into the City, after gaining ... a success more brilliant even than that of Papirius; indeed the glory of conquering the Samnites was largely diverted [from Papirius to his legates], Publius Decius and Marcus Valerius, of whom, at the next election, the people with great enthusiasm made the one consul and the other praetor”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 40: 20-21).

Livy enlarged on this at the start of his record of the consular year that followed:

-

“In recognition of his remarkable conquest of Etruria, Fabius was continued in the consulship, and was given Decius for his colleague. Valerius was for the fourth time chosen praetor”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 1).

The ‘fasti Triumphales’ record that, in the fictitious dictator year of 309 BC:

-

✴Papirius, as dictator, was awarded a triumph over the Samnites on 15th October; and

-

✴Fabius, as proconsul, was awarded a triumph over the Etruscans on 13th November.

In fact, as explained above, the likelihood is that, if these triumphs were actually awarded at all, they were awarded during Fabius’ second consulship: there is no earlier evidence that he subsequently served as proconsul in Etruria, and nothing that casts doubt on Liv’s assertion t that he held his second and third consulships in consecutive years.

It is certainly likely that Fabius’ second consulship culminated in the award of a triumph: as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 456) pointed out, he:

-

“... was the most important Roman general of the Samnite wars and, among his exploits, his campaign in [his second year as consul] had a significance second only to his great victory [over the Samnites, Gauls and Etruscans] at Sentinum in 295 BC.”

Events of 308 BC

Decius in Etruria

As noted above, Livy recorded that, while Fabius was fighting with some success on the borders of Samnium, Decius was also successful in his campaigns in Etruria.

Truce with Tarquinii

Livy first noted that Decius:

-

“... frightened the people of Tarquinii into furnishing corn for his army and seeking a truce for 40 years”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 6).

According to Diodorus, after both consuls had settled matters with the Samnites in the territory of the Marsi, they crossed

-

“... the territory of the Umbrians and invaded Etruria, which was hostile, and took by siege the [now-unknown] fortress called Caerium. When the people of the region sent envoys to request a truce, the consuls made truces:

-

✴for 40 years with the Tarquinians; but

-

✴for only one year with all of the other Etruscans”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 44: 8).

[30 year truces with Perusia, Cortona and Arretium in 310/9 BC ??]

Raids in Volsinian Territory

According to Livy, after Decius had agreed the new 40-year truce with Tarquinii, he:

-

“... captured by storm a number of strongholds belonging to the people of Volsinii and dismantled some of them, lest they should serve as a refuge for the enemy. By devastating far and wide, [Decius] made himself so feared that nomen omne Etruscum (all who bore the Etruscan name) begged him to grant them a foedus (treaty). They were denied this privilege, but truces for a year was granted them, [in return for which] they were required to furnish the Roman army with a year's pay and two tunics for each soldier”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 6-8).

-

The identity of ‘Caerium’ is unknown, but it was presumably one of the ‘strongholds belonging to the people of Volsinii’ that, according to Livy (below), were captured by Decius in 308 BC.

Livy

Livy recorded that:

-

“The consuls [of 308 BC] cast lots for the commands, Etruria falling to Decius and Samnium to Fabius:

-

✴[Fabius put down pro-Samnite revolts in the territory of the Marsi and the Paeligni].

-

✴Then, as we shall see, Decius fell back towards Rome while Fabius marched from Samnium to engage with and defeat an Umbrian army that was camped at Mevania.

Reconciliation of these Sources

We might reasonably follow Livy by placing Fabius in Samnium and Decius in Etruria at the start of the consular year.

Decius in Etruria

Livy had Decius’ campaign begin at Tarquinia. Since the truce between the Romans and the Tarquinians had ended in 311 BC, it seems likely that they had participated in the Etruscan army that threatened Sutrium at that time. Thus, after the Etruscans’ defeat in the ‘famous battle’ near Perusia, it is entirely possible that Decius was able to bully them into supplying his army and agreeing a new 40 year truce (as Livy stated). Diodorus also recorded the agreement of this truce, albeit that he did not record the circumstances in which it was agreed. Livy’s record that Decius then marched north into the territory of Volsinii is equally unsurprising: as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 531) observed, Volsinii was now probably:

-

“... the centre of Etruscan resistance to Rome.”

Oakley also observed that the Volsinian strongholds that, according to Livy, Decius captured might have included Diodorus’ ‘Caerium’ . In other words, the brief accounts by Diodorus and Livy of Decius’ engagements in Etruria in 308 BC are broadly consistent and comprehensible.

Both Diodorus and Livy agreed that this Etruscan War ended with the agreement of one-year truces with:

-

✴‘all of the other Etruscans’ (Diodorus); or

-

✴‘all who bear the Etruscan name’ (Livy).

This suggests that they both relied on one or more then-extent sources that made this claim. However, any such claim is difficult to take at face value: for example, there is no evidence that Caere, with whom (according to Livy) Rome had agreed a truce of 100 years in 353 BC, had participated in either the siege of Sutrium in 310/9 BC or the fighting in upper Etruria that followed it. Why, then, did nomen omne Etruscum (all who bore the Etruscan name, including, for example, Caere) feel so intimidated by Decius’ depredations in 308 BC that they sought a treaty with Rome and, when this was refused, settled for a truce of only a year?

It is interesting to note that Livy used the expression omne nomen Etruscum in connection with the Etruscan War of the 350s, in which only Tarquinii, Falerii and Caere were mentioned by name. In 356 BC, the consul Marcus Fabius Ambustus:

-

“... who was operating against the Faliscans and Tarquinians, met with a defeat in the first battle. ... This led to a rising of omne nomen Etruscum and, under the leadership of the Tarquinians and Faliscans, they marched to the salt-works”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 17: 3 and 6).

William Harris (referenced below, at p. 46 observed that:

-

“Not much trust is to be placed in the statement by Livy that the whole Etruscan nomen took part in the fighting against Rome [at this time]. .... the only reliable element in this narrative is the result:

-

✴the truce of 100 years [that the Romans made with Caere in 353 BC]; and

-

✴... the truce of 40 years that [they] made with Tarquinii and Falerii in 351 BC ...”.

In other words, the phrase omne nomen Etruscum in this context seems also to have been applied to those who were directly involved in the conflict in question, on this occasion to Tarquinii, Falerii and Caere. Thus, the similar expression that he used in 308 BC would relate to all those affected by Decius’ depredations, presumably with the exception of Tarquinii. This is probably why Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 531) assumed that the one-year truces of 308 BC had been agreed with:

-

“... Volsinii and other Etruscan states.”

It would be reasonable to assume that these other states included a number that, like Tarquinii, and Volsinii, had not had truces in place at the start of 308 BC. Whether or not any or all of Arretium, Cortona and Perusia broke their recently-agreed 30 year truces at this point is impossible to say.

Conclusion: Roman Activity in Umbria in 308 BC

The only significant divergence between the accounts of Diodorus and Livy relates to events in Umbria:

-

✴Diodorus had a Roman army crossing Umbrian territory in order to invade Etruria; while

-

✴Livy had it marching into Umbria after the invasion of Volsinian territory, with the sole purpose of engaging with the Umbrians at Mevania.

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 531) suggested the part of this apparent difference might be resolved by assuming that:

-

“... the Romans marched through Umbria, fought the Etruscans, and returned once more to Umbria.”

In other words, the only significant difference between the two accounts is that Diodorus either ignored or was unaware of Livy’s source(s) for Fabius’ victory over the Umbrians at Mevania.

Livy is our only surviving source for this battle. He began his account of it as follows:

-

“The tranquillity that now obtained in Etruria [after the agreement of the one-year truces mentioned above] was disturbed by a sudden defectio (insurrection) of the Umbrians, who had escaped all the distress of war, except that [a Roman] army had passed through their territory ”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 8).

Earlier Incursions of Umbrian Territory

These incursions into Umbrian territory were presumably those that Livy and/or Diodorus had recorded in 310/9 BC:

-

✴According to Diodorus, early in Fabius’ consulship, Fabius drove the Etruscan army that was then besieging Sutrium back into its camp and then outflanked the Etruscan reinforcements that were sent to reinforce them by slipping away into Umbrian territory in order to mount a surprise attack in upper Etruria:

-

“While the Etruscans were gathering in great numbers against Sutrium, Fabius marched without their knowledge through the country of their [Umbrian] neighbours into upper Etruria, which had not been plundered for a long time. Falling upon it unexpectedly, he ravaged a large part of the country; and, in a victory over those of the inhabitants who came against him, he slew many of them and took no small number of them alive as prisoners”, (‘Library of History’, 20: 35: 2-3).

-

✴According to Livy, Fabius’ covert departure involved crossing the Ciminian Forest and climbing to the top of mons Ciminius (the Ciminian Mountain), from whence he looked down:

-

“ ... over the rich ploughed fields of Etruria, [which] he sent his soldiers to plunder. After the Romans had [accumulated] enormous booty, they were confronted by certain improvised bands of Etruscan peasants ... Having slain or driven off these men and wasted the country far and wide, the Romans returned to their camp, victorious and enriched with all manner of supplies”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 36: 11-13).

-

This expedition was apparently initially counter-productive, since:

-

“... instead of putting an end to the war, it only gave it a wider range. For the district lying about the base of [the mountain] had felt the devastation, and this had aroused not only Etruria to resentment but also the neighbouring parts of Umbria”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 37: 1).

-

As discussed above, if we take these two accounts together, we might reasonably assume that, having descended from the Ciminian Mountain, Fabius crossed the Tiber and marched north through Umbrian territory (perhaps along the proto-Amerina), before recrossing the river into upper Etruria.

-

✴We then come to Livy’s ‘famous battle’: although he placed it at Sutrium, he conceded that some of his sources claimed that it was:

-

“... fought on the [north] side of the Ciminian Forest, near Perusia, and that Rome was in a panic lest the army should be surrounded and cut off ... by the Etruscans and Umbrians rising up on every hand”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 37: 11).

-

Diodorus (like some of Livy’s sources) located this battle near Perusia, and this would account for the fact that, after the victory, Fabius agreed truces with Arretium, Cortona and Perusia. It would certainly be unsurprising if the Umbrians, across whose territory the Romans had marched to reach the site of the battle, had indeed sent men to support their Etruscan neighbours.

Muster of an Umbrian and Etruscan Army ?

According to Livy, after Decius’ campaign in Etruria in 308 BC, the Umbrians (for whatever reason) decided to take on the might of Rome:

-

“Calling up all their fighting men, and magna parte Etruscorum ad rebellionem compulsa (pushing the great part of the Etruscans to rebel), they mustered so large an army that they boasted ... that they would leave Decius behind them in Etruria and march off to the assault of Rome”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 41: 9).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 528) suggested that Livy had inserted this passage in order explain why he had described this Umbrian revolt at greater length than any other event of 308 BC:

-

“[Livy’s] justification for this elaboration is provided by:

-

✴the Umbrians’ encouraging [of] the Etruscans to rebel;

-

✴... their [intention of] outflanking Decius; and

-

✴... [their threat] to march on Rome itself.”