Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Wars in Gaul and Etruria (283 - 1 BC)

Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Wars in Gaul and Etruria (283 - 1 BC)

Gallic War (283 BC)

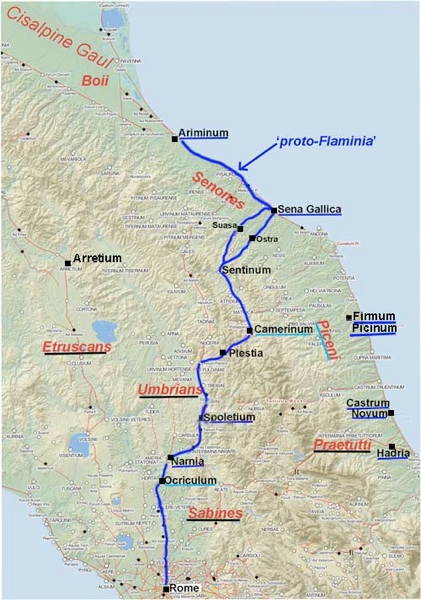

Colonies underlined in blue:

Narnia (299 BC);

Hadria, Castrum Novum and Sena Galica (280s BC - see below);

Later colonies: Ariminum (268 BC); Firmum Picinum (264 BC); Spoletium (241 BC)

Roman allies underlined in turquoise: Camerinum (310 BC); Ocriculum (308 BC); and the Picenti (299 BC)

Defeated peoples underlined in black: Umbrians (308 BC);

some Etruscans, including Arretium, Perusia and Volsinii (294 BC); Sabines and Praetuttii (290 BC)

Blue road (‘proto-Flaminia’ = most convenient route from Rome to the Adriatic coast in 295 - 220 BC

(see, for example, Federico Uncini (referenced below, at pp. 21-9)

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Death of the Praetor L. Caecilius and Roman Envoys (283 BC)

Polybius recorded that, in 283 BC, ‘the Gauls’ besieged Arretium, an Etruscan town that had agreed a truce for 40 years with the Romans in 294 BC. Polybius did not identify the Gallic tribes that had participated in this assault, but they would have included those settled to the north of the Apennines, including the Insubres (around modern Milan), the Boii and the Senones:

“The Romans went to the assistance of [Arretium] and were beaten in an engagement under its walls. Since the strategos (praetor) Lucius had fallen in this battle, Manius Curius [Dentatus] was appointed in his place. He sent ambassadors to treat with the Gauls for the release of prisoners, but the Gauls treacherously murdered them”, (‘Histories’ 2: 19: 7-10).

The summary of Livy’s now-lost Book 12 gave a different account of these events:

“When Roman envoys were killed by Gallic Senones, war was declared against the Gauls. The praetor L. Caecilius and his legions were killed by them” (‘Periochae’, 12:1 ).

Probably drawing on Livy’s now-lost account, Paulus Orosius recorded that:

“... during the consulship of [P. Cornelius] Dolabella and [Cn.]Domitius [Calvinus: i.e., 283 BC], the Lucanians, Bruttians, and Samnites made an alliance with the Etruscans and Senonian Gauls, who were attempting to renew war against the Romans. The Romans sent ambassadors to dissuade the Gauls from joining this alliance, but the Gauls killed them. The praetor Caecilius was sent with an army to avenge their murder and to crush the uprising of the enemy. However, he was overwhelmed by the Etruscans and Gauls and perished. Seven military tribunes were also slain in that battle, many nobles were killed, and 30,000 soldiers likewise met their death”, (‘History against the Pagans’, 3: 22).

Reconciliation of the Polybian and the Livian Traditions

Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 429) observed that:

“Both traditions must refer to the death of the same Roman commander (presumably L. Caecilius Metellus Denter, the consul of 284 BC, the only L. Caecilius known to be active at that time) and to the same occasion.”

In other words, the man that Polybius identified only as ‘the praetor Lucius’ must have been L. Caecilius Metellus Denter, the consul of 284 BC. Since the fasti Capitolini do not mention his death while consul, the war in which he was killed (as praetor) must have taken place in 283 BC. Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 431) argued that, since:

“... Metellus seems to have failed to bring the Gauls to a decisive battle within his actual year of office [as consul in 284 BC], I would suggest that he then was elected praetor for 283 BC, probably in absentia.”

Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 438) observed that:

“The Livian epitomes hint at an even more dramatic story [than that of Polybius]: although the massacre of the envoys is a casus belli (as in Polybius), the death of the praetor L. Caecilius ... follows. This version is a bit illogical: it may be asked why the praetor was at Arretium if the Senones killed the Roman legati in their [own territory], as all the sources seem to agree.”

Brennan argued (at p. 438) that:

“The following is probably the most we can make out of our conflicting sources:

✴Near the end of consular year 284 BC, certain Gauls ... besieged the pro-Roman town of Arretium.

✴The Romans sent the consul [Metellus] to relieve it.

✴[Since Metellus was] unable to achieve this ... [before the end of the consular year], he was elected praetor ... for the following year.

✴In early 283 BC, Metellus, while still in charge of what had been his consular army, ... [returned to] Arretium ..., [where] the Gauls ... were now joined by rebel Etruscans.

✴[Metellus] met his death at the hands of their combined forces.

✴As it was still quite early in the year, the Romans elected a praetor suffectus, the experienced consul M’ Curius Dentatus, to replace Metellus.”

It would have been at this point that Curius sent envoys into the territory of the Senones to negotiate the release of prisoners of war, a decision that led to their murder.

Appian

Appian gave two essentially identical accounts of an occasion on which the Senones murdered Roman envoys in 283 BC:

✴“The Senones, although they had a treaty with the Romans [see below], nevertheless furnished mercenaries against them. The Senate therefore sent an embassy to them to remonstrate against this infraction of the treaty. Britomaris, the Gaul, being incensed against the Romans on account of his father (who had been killed by the Romans while fighting on the side of the Etruscans in this very war), murdered the ambassadors , [despite the fact that] they held the [herald's staff] and wore the garments that symbolised their office. He then cut their bodies in small pieces and scattered them in the fields”, (‘Gallic Wars’, 2.13).

✴“Once, a great number of the Senones, a Gallic tribe, aided the Etruscans in war against the Romans. The latter sent ambassadors to the towns of the Senones and complained that, while they were under treaty stipulations, they were furnishing mercenaries to fight against the Romans. Although they bore the [herald's staff] and wore the garments of their office, Britomaris cut them in pieces and flung the parts away, alleging that his own father had been slain by the Romans while he was waging war in Etruria”, (‘Samnite Wars’, 2.13).

Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 426) observed that, despite some differences, these two accounts probably relate to the events described by Polybius (above), and that they:

“... contribute some details ... that are not found in other authors:

✴the slaughter of the [envoys by the Senones] is put in the context of an Etruscan war;

✴the Romans sent these [envoys] to the towns of the Senones ... because, [although they had a treaty with the Romans], they had furnished mercenaries to the Etruscans ... ; and

✴the Gaul Britomaris ... , who had lost his father in this war, killed the legates with his own hands.”

Brennan reconciled the accounts of Polybius and Appian by suggesting (at p. 438) that, soon after the election of the new consuls of 283 BC (see below), the Romans:

“... prepared to advance into Etruria. In connection with this campaign, [the praetor suffectus] M’ Curius Dentatus sent [envoys] to the Senones [Polybius] in an effort to:

✴regain Roman prisoners-of-war (Polybius); and

✴dissuade them from assisting the Etruscans as mercenaries (Appian).”

In summary, although the detail of the events that led to the Romans’ war with the Senones are confused, it is likely that the casus belli was the murder of envoys that Curius (as praetor suffectus) had sent to the Senones.

Conquest of the Senones (283 BC)

According to Robert Broughton (referenced below, at p. 188), the consuls elected for 283 BC were P. Cornelius Dolabella and Cn, Domitius Calvinus Maximus. According to Polybius, when news of the murder of the envoys that had been sent to the Senones reached Rome, early in the consular year:

“... the infuriated Romans sent an expedition against [the Gauls] that was met by the [Gallic] tribe called the Senones. This [enemy] army was cut to pieces in a pitched battle, [following which], the rest of the tribe was expelled from [their territory on the Adriatic coast]. The Romans sent the first colony that they ever planted in Gaul [to this territory]: this colony was named Sena [Gallica] for the tribe that had formerly occupied it”, (‘Histories’ 2: 19: 10-12).

Polybius did not identify the Roman commander who defeated the Senones and confiscated their territory. Some scholars identify him as M’ Curius Dentatus (who, as we have seen, had sent ambassadors to treat with the Gauls the suffect pretor in 284 BC): for example, Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 215) argued that the early viritane settlement in the area around Pisaurum (evidenced by presence in this area of the Camilia voting tribe) had immediately followed:

“... the extermination of the Senones in 284 BC, which carried the sure sign of Curius Dentatus, [who had famously exterminated the Sabines in 290 BC - see below]”, (my translation).

However, Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 425) pointed out that, although Polybius recorded that Curius sent envoys to the Senones in that year, he:

“... does not state that it was [Curius] who [either] marched against the Senonian Gauls or planted the colony [of Sena Gallica], an erroneous supposition that has caused much confusion.”

He plausibly argued (see p. 437) that Curius did no more than replace L. Caecilius as praetor and send envoys ambassadors to the Gauls, after which he departed for southern Italy, where he triumphed over the Lucanians in southern Italy (see below).

Appian (again in two essentially identical accounts) identified the Roman commander who defeated the Senones and confiscated their territory as Dolabella, who was, as we have seen, one of the consuls of 283 BC:

✴The consul [Dolabella], who learned of this abominable deed while he was on the march, moved with great speed against the towns of the Senones by way of the Sabine country and Picenum, and ravaged them all with fire and sword. He reduced the women and children to slavery, killed all the adult males without exception, devastated the country in every possible way, and made it uninhabitable for anybody else. He then carried off Britomaris alone as a prisoner for torture”, (‘Gallic Wars’, 2.13).

✴The consul [Dolabella], who learned of this abominable deed while he was on the march, abandoned his campaign against the Etruscans and dashed with great rapidity by way of the Sabine country and Picenum against the towns of the Senones, which he devastated with fire and sword. He carried their women and children into slavery, and killed all the adult youth except a son of Britomaris, whom he reserved for awful torture and led in his triumph”, (‘Samnite Wars’, 2.13).

This is confirmed by:

✴Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who referred to:

“... P. Cornelius [Dolabella], who, while consul [in 283 BC], had waged war on the whole tribe of Gauls and had slain all their adult males, ...”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 19: 13: 1); and

✴Florus recorded that:

“... near the lacus Vadimonis [see below] in Etruria, Dolabella destroyed all that remained of the tribe [of the Senones], so that none might survive of the race to boast that he had burnt the city of Rome [in the early 4th century BC]”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 1: 8: 21).

In short, all of the surviving sources that identify the commander who destroyed the Senones as P. Cornelius Dolabella, the consul of 283 BC.

Colony at Sena Gallica

There are two distinct traditions for the date of the foundation of the colony at Sena Gallica:

✴An entry in the surviving summary of Livy’s now-lost Book 11 records that:

“Colonies were founded at Castrum [Novum in Picenum], Sena [Gallica] and Hadria”, (‘Periochae’, 11: 7).

This book probably began in 290 BC and certainly ended before the death of the praetor L. Caecilius in 283 BC (which, as we have seen, was the first event recorded in Book 12). If the entries in the Perioche are in date order, then these three colonies would have been founded:

•after the double triumph of M’ Curius Dentaus recorded at 11: 5, (which he celebrated as consul of 290 BC, over the Samnites and the Sabines); and

•before the census recorded at 11: 9, which Robert Broughton (referenced below, at p. 184 and note 2) dated to 289 BC.

✴However, as we have seen:

•according to Polybius, the colony was founded in 283 BC, on land that the Romans had confiscated from the Senones; and

•although Appian did not mention the foundation of the colony, he did record that, in revenge for the murder of the legates, Dolabella, as consul in 283 BC, had:

“... ravaged [all of the towns of the Senones] with fire and sword. He reduced the women and children to slavery, killed all of the adult males without exception, devastated the country in every possible way, and made it uninhabitable for anybody else”, (‘Gallic Wars’, 2.13).

In fact, these records can probably be reconciled: as Michael Fronda (referenced below, at p. 429) pointed out,:

“In his surviving books, Livy reported colonial foundations in one of two ways: he either:

•stated that a colony was founded, using formulae as colonia(e) deducta(e) or deduxerunt coloniam/-as: or

•mentioned that legislation was passed to found a colony at some later point, employing future constructions such as ut colonia(e) deducere tur/ -ntur or colonia(e) deducenda(e).

[However], no matter what phrase Livy uses, [in the original], the Periochae ... invariably report colonial foundations with the formula colonia(e) deducta(e).

In other words, in this case, we can reasonably assume that the legislation for the foundation of all three colonies was passed in 290-89 BC, but we cannot automatically assume that all three were then immediately founded ‘on the ground’. It is, of course, extremely unlikely that the Romans would have passed enabling legislation for the foundation of colonies on land that was not under Roman control:

✴This is not a problem in relation to the colonies of Castrum Novum in Picenum and at Hadria since, according to Florus, Curius had confiscated the necessary land during his conquest of the Sabines in 290 BC, when:

“... the Romans laid waste with fire and sword all the tract of country that is enclosed by the Nar [on which stood the colony of Narnia], the Anio and the sources of the Velinus, and bounded by the Adriatic Sea. By this conquest, so large a population and so vast a territory was reduced, that even [Curius] could not tell which was of greater importance”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 1: 10).

✴On the other hand, it is a problem for Sena Gallica unless there are grounds for believing that the land on which it was subsequently founded was in Roman hands in ca. 290 BC.

An odd aspect of Appian’s account of the events of 283 BC (above) might throw some light on this potential problem: he recorded that, in 283 BC, the Roman legates who were sent to the Senones had argued that the fact that Senonian mercenaries were taking service with Rome’s enemies was represented a violation of a Romano-Senonian treaty. This information is not found in any of our other surviving sources, but Nathan Rosenstein (referenced below, at p. 38) argued that the Romans had probably forced this treaty on the Senones after their victory over the Samnites, Gauls, Etruscans and Umbrians at Sentinium (on the border of Senonian territory) in 295 BC, and that they might also have forced them to cede a portion of their land at this time. If so, then it is at least possible that the Romans passed legislation enabling the foundation of a colony here in 290-89 BC, but that its foundation was postponed until the land in question was more securely under Roman control, which would have been the case after the conquest of 283 BC.

It seems that Sena Gallica was formally a maritime citizen colony, as evidenced by the fact that (according to Livy, ‘History of Rome’, 27: 38: 4) it was among seven such colonies that pleaded their ‘sacrosancta vacatio militiae’ [notionally inviolable exemption from military service] in 207 BC. It is often asserted that only 300 citizen settlers were enrolled for this type of colony, and that this was therefore the case at Sena Gallica. However, the number of colonists is recorded for only 6 of about 20 known maritime colonies:

✴Tarracina, which also appears in Livy’s list such colonies in 207 BC; and

✴5 founded in 194 BC (Livy, ‘History of Rome’, 32: 29: 3).

It is true that the number of colonists in each of these 6 was indeed 300, but that does not prove that this necessarily applied at Sena Gallica in 283 BC (or at any other 13 known colonies of this type). Indeed, according to Giuseppe Lepore (referenced below, in the English abstract of his paper), the archeological evidence suggests that this:

“... first [maritime colony] on the Adriatic [had] the shape and size of a [Latin colony], recalling the situation that, 20 years later, characterised the [Latin] colony of Ariminum [on the northern border of the ager Gallicus]. The new [evidence gained from recent excavations] allows us to hypothesis that Rome adopted a new form of [citizen colony as part of] its ‘Adriatic policy’.”

In the body of his paper (at pp. 231-2), he expanded as follows:

“We can recognise [from the new archeological data] a city of dimensions quite unlike those of other maritime colonies: we are looking at [an area of some] 18 hectares, compared with 2-2.5 hectares for the older maritime colonies on the Tyrhenian coast” (my translation).

He suggested that this new model had also applied at the citizen maritime colony of Castrum Novum in Picenum, which, as we have seen, had been founded to the south (on land recently confiscated from the Praetutti) at about the same time. More recently, Frank Vermeulem (referenced below, at p. 193 pointed out that the Adriatic coastal plain had been essentially unurbanised at the start of the 3rd century BC, and argued (at p. 194) that the series of colonies that the Romans built here shortly thereafter can be:

“... seen as successful weapons used by Rome to take full possession of central Italy.”

He noted (at p. 195) that our surviving sources record five such colonies in the two decades following the conquest of the ager Gallicus:

✴the citizen colonies of Castrum Novum (ca. 290 BC) and Sena Galica (283 BC); and

✴the Latin colonies of Hadria (ca. 290 BC), Ariminum (268 BC); Firmum Picinum (264 BC);

and observed that, on the basis of archeological evidence:

“... despite their different legal status, they [apparently had] characteristics that [were] very similar to those of quite large population centres, [and would have] generated a strategically well-balanced urban strip along the coast, controlling the sea and the now expanded easternmost part of the ager Romanus.”

Federico Uncini (referenced below, at pp. 21-9) suggested that, before the building of Via Flaminia in 220 BC, the Romans could have reached Sena Gallica using existing roads (including those that he designated as the proto-Flaminia illustrated on the map at the top of the page). Nevertheless, the lines of communication were long and, as Graham Mason (referenced below, at p. 82) observed, since it would not have been easily provisioned from Rome, the colonists would have needed to provide for themselves by farming the broad alluvial plain on which it was located.

Victory at the Lacus Vadimonis (283 BC)

Ancient Latin colonies at Sutrium and Nepete protected Rome

Treaties agreed with Camerinum (310/9 BC); Ocriculum (308 BC); and the Picenti (299 BC)

Latin Colony of Narnia founded in 299 BC

40 year truces agreed with Arretium, Perusia and Volsinii in 294 BC

Lands of the Sabines and Praetuttii confiscated in 290 BC

Latin colony of Hadria and citizen colony of Castrum Novum founded in ca. 290 BC

Citizen colony of Sena Gallica founded in ca. 290 BC (Livy) or 283 BC (Polybius)

According to Polybius, still in 283 BC:

“Seeing the expulsion of the [Gallic] Senones [from their territory on the Adriatic coast], and fearing the same fate for themselves, the [neighbouring Gallic tribe known as the] Boii:

✴made a general levy [among their own people];

✴summoned the Etruscans to join them; and

✴set out to war [against Rome].

They mustered their [combined] forces near the lacus Vadimonis and there gave the Romans battle”, (‘Histories’, 2:20).

Although this ancient lake no longer exists, its general location is known: it was in Etruscan territory (on the left bank of the Tiber), about:

✴50 km southeast of the Etruscan city-state of Volsinii; and

✴70 km east of the Etruscan city-state of Tarquinii.

More importantly for the Romans, it was about 40 km north of the Latin colonies of Sutrium and Nepet, which guarded the way to Rome.

Polybius gave no description of the battle at the lacus Vadimonis, simply noting that:

“... the Etruscans suffered the = loss of more than half their men, while scarcely any of the Boii escaped”, (‘Histories’, 2:20).

However, it seems that the Romans’ victory here was not completely decisive: according to Polybius, in the following year (282 BC), the Boii and the Etruscans:

“... joined forces once more: after mobilising even those of them who had only just reached manhood, they gave the Romans battle again. It was not until they had been utterly defeated in this engagement that they humbled themselves so far as to send ambassadors to Rome and to make a treaty”, (‘Histories’, 2:20).

Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 427) observed that:

“Although Polybius does not name the Roman commander [at the lacus Vadimonis], later tradition unanimously ascribes the victory to Dolabella.”

He cited (inter alia):

✴Florus

“... near the Lake of Vadimo in Etruria, Dolabella destroyed all that remained of the [Gallic Senones], so that none might survive of the race to boast that [his ancestors] had burnt the city of Rome”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 1: 8: 21); and

✴Eutropius

“After an interval of a few years [after the end of the Third Samnite War in 290 BC], the forces of the Gauls united with those of the Etruscans and the Samnites against the Romans; but, as they were marching to Rome, they were cut off by the consul Cnaeus [sic] Cornelius Dolabella”, (‘Abridgement of Roman History’, 2.10).

He concluded that, when the Romans became aware that the Etruscans and the Boii were mustering a their men at the lacus Vadimonis:

“Dolabella must have hurried back from [devastating] the land of the Senones to return to his original mission, a campaign against the Etruscans.”

Polybius also failed to identify the Roman commander who defeated the remnants of the enemy armies after the battle at the lacus Vadimonis. However, Appian seems to have identified him as Dolabella’s consular colleague, Cn. Domitius Calvinus:

“A little later [i.e. immediately after Dolabella had ravaged and confiscated their territory], those Senones who were serving as mercenaries, having no longer any homes to return to, fell boldly upon the consul Domitius. After he defeated them, they killed themselves in despair. Such punishment was meted out to the Senones for their crime against the ambassadors”, (‘Gallic Wars’, 2.13).

Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 427) observed that this victory:

“... is found only in Appian. It is not immediately clear what Appian is talking about. Some scholars have (wrongly) thought Appian is referring to Vadimon. ... I would suggest that Domitius' conflict with the Senonian Gauls [actually] belongs to the period immediately following Vadimon, but still in his consular year of 283 BC.”

He suggested (at p. 428) that the following surviving fragment from Cassius Dio might support this hypothesis:

“... When the enemy saw that another general had also arrived, they ceased to heed the common interests of their expedition: each cast about to secure his own safety, as is the common practice of those who:

✴form a union that is not cemented by kindred blood; or

✴make a campaign without common grievances; or

✴lack a single commander:

... And so, arranging their flight, each in the way that seemed safest in his own judgment ... ”, (‘Roman History’, 8: fragment 38)

As Brennan observed (at p. 428):

“It has long been thought that [the now-unidentified anti-Roman alliance was that of the] Etruscans, Boii and Senones, at the time of Vadimon: this must be correct. I would further suggest that the [unidentified approaching second Roman commander] is the consul Domitius, who had now moved into Etruria ... to support his colleague ... Dolabella. It is not impossible that, after defeat at Vadimon and the splintering of the coalition (described here by Dio), a band of desperate Senones attacked Domitius, with dire results [for themselves].”

Final War with the Etruscans (282 - 280 BC)

Our surviving sources for the period immediately following the Romans’ victory at the lacus Vadimonis are very sparse::

✴according to the surviving summary of Livy’s now-lost Book 11, wars against the Volsinians and Lucanians broke out in 282 BC (‘Periochae’, 11: 12); and

✴the ‘Fasti Triumphales’ record triumphs awarded to:

•Q. Marcius Philippus, over the Etruscans in 281 BC; and

•T. Coruncanius, over the Vulsinienses and Vulcientes (i.e. over Volsinii and Vulci) in 280 BC.

Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, 2010, at p. 42) asserted that:

“... the [Romans’] last war with Etruria ended in [280] BC. It is usually assumed that, on this occasion, Caere, Vulci, Volsinii and Tarquinii lost part of their land.”

Read more:

Vermeulen F., “The Urban Landscape of Roman Central Adriatic Italy”, in:

De Light L. and Bintliff J. (editors), “Regional Urban Systems in the Roman World, 150 BCE - 250 CE” (2020) Leiden, at pp. 188–216

Lepore G., “La Colonia di Sena Gallica: un Progetto Abbandonato?” , in:

Chiabà M. (editor), “Hoc Quoque Laboris Praemium: Scritti in Onore di Gino Bandelli”, (2014) Trieste, at pp. 219- 42

Rich J., “The Triumph in the Roman Republic: Frequency, Fluctuation and Policy”, in:

Lange C. J. and Vervaet F. (editors), “The Roman Republican Triumph: Beyond the Spectacle”, (2014 ) Rome, at pp. 197-258

Rosenstein N., “Rome and the Mediterranean: 290 to 146 BC”, (2012) Edinburgh

Fronda M., “Polybius 3.40, the Foundation of Placentia and The Roman Calendar (218–217 BC)”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 60:4 (2011) 425-57

Roselaar S., “Public Land in the Roman Republic: A Social and Economic History of Ager Publicus in Italy, 396 - 89 BC”, (2010) Oxford

Sisani S., “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

Uncini F., “La Viabilità Antica nella Valle del Cesano”, (2004) Monte Porzio

Brennan T. C., “M’. Curius Dentatus and the Praetor's Right to Triumph”, Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 43: 4 (1994), 423-39

Mason G., “The Agrarian Role of Coloniae Maritimae: 338-241 BC”, Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 41:1 (1992) 75-87

Broughton T. R. S., “Magistrates of the Roman Republic: Volume 1: 509 BC - 100 BC”, (1951) New York

Return to Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)