Lombard Invasion (568 AD)

The Lombards, who had settled north of the Alps, first entered Italy as allies of the Byzantine general, Narses, in 552. Narses subsequently fell from imperial favour, and it might have been at his instigation that the Lombards invaded Italy, led by King Alboin, in 568. Narses seems to have died soon after.

The Lombard army had little difficulty in taking most of northern Italy. Pavia, which had been King Theoderic’s northern capital, held out for a while but fell to them in 572 after a three-year siege. It now became the capital of the Lombard Kingdom of Italy.

Lombard Interregnum

King Alboin was murdered by his wife in ca. 572, at which point she fled to the court of Longinus, the Byzantine Exarch at Ravenna. During the 10-year interregnum that followed, power devolved to some 30 Lombard dukes. In ca. 576, the Byzantines took the opportunity provided by this apparent power vacuum to attempt to recoup some of the territory that they had lost. Baduarius, the son-in-law of the emperor Justin II, assembled a considerable army at Ravenna and marched into the occupied territory. However, the attempt failed.

In ca. 575, one of the rebellious Lombards, Faroald, who seems to have been a mercenary in the Byzantine army, seized Classe (the port of Ravenna) along with a considerable amount of plunder. He then marched south and conquered a swathe of territory that extended from the Adriatic coast along the valley of Spoleto, taking in Spoleto itself, Camerino, Norcia, Foligno and Assisi to the north, and Terni, Rieti and the Sabine lands to the south. He thus became Duke Faroald I, and his territory became known as the Duchy of Spoleto. (Another Lombard mercenary managed to establish the Duchy of Benevento to the south at about the same time).

Droctulf (or Drocton), a Byzantine general who had entered Italy with the Lombards, emerged as the leader of the Byzantine resistance to their expansion in Italy. He retook Classe in ca. 576: his epitaph in San Vitale, Ravenna recorded that: “when Faroald withheld by treachery Classe, ... [Drocton] conquers and overcomes numberless Langobard bands ...”.

Kings Authari (584-90)

The Emperor Maurice established the Exarchate at Ravenna in 584, in order to address the Lombard presence in Italy. He also negotiated an anti-Lombard alliance with Childepert II, king of the Franks. This threat prompted the Lombard dukes of northern Italy to elect Authari as their king.

The Exarch Smaragdus, who led the Byzantine resistance to the Lombards from Ravenna, made little headway against Authari, mainly it seems because of poor communications with the army that Childepert II sent to assist him. This army duly withdrew across the Alps, and Smaragdus was recalled to Byzantium (589). At this time, Authari strengthened his position by marrying Theodelinda, the daughter of the Duke of Bavaria.

When Authari died in 590, Agilulf (who might have poisoned him) seized his crown and his wife, the redoubtable Theodelinda.

Pope Gregory I (590 - 604)

The emergence of King Agilulf broadly coincided with the election of Pope Gregory I and the arrival at Ravenna of a new Byzantine exarch, Romanus.

In his “Dialogues”, Gregory I set out how he viewed the political scene that he inherited:

-

“The barbarous and cruel nation of the Lombards ... left their own country, and invaded ours: by reason whereof the people, which before ... were like thick corn-fields, remain now withered and overthrown: for cities are wasted, towns and villages spoiled, churches burnt, monasteries of men and women destroyed, farms left desolate, and the country remains solitary and void of men to till the ground, and destitute of all inhabitants: beasts possess those places, where before great plenty of men did dwell”.

In 592, shortly after he succeeded his father as Duke of Spoleto, Ariulf seized Perugia, while Duke Arichis of Benevento threatened Naples. In the face of this duel threat to Rome itself, and in the absence of any military support from Ravenna, Gregory I paid a considerable bribe to secure a truce with the Ariulf. Romanus refused to recognise this truce, and withdrew forces from Narni and Rome in order to retake Perugia. Gregory I bitterly described Romanus’ action as “abandoning Rome so that Perugia might be held”. Romanus managed to take a number of cities from the Lombards, including Todi, Amelia and Perugia: according to Paul the Deacon (‘History of the Romans’, 4:8) , Perugia fell because Duke Maurice (the first official of this title for whom we have a name) defected from the Lombards to the Romans.

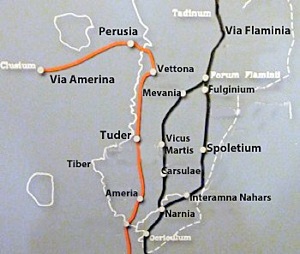

Since a large stretch of the Via Flaminia lay in the Duchy of Spoleto, the Via Amerina (which had originally swung west from Perugia to Chiusi) was subsequently extended to the north east to provide an alternative route from Rome to Ravenna through what is usually called the Byzantine corridor. This territorial division between:

-

✴the Lombard Kingdom to the north;

-

✴the Byzantine corridor from Rome to Ravenna; and

-

✴the independent Lombard duchies of Spoleto and Benevento;

provided the backdrop to the history of central Italy for the next two centuries. Perugia became a garrison town at the heart of a newly constituted duchy, an administrative division administered by a duke who reported to the exarch. Thomas Noble (referenced below) regarded it “something of a historical accident, whose only reason for being was to secure communications between Rome and Ravenna”. However, the Byzantine corridor and the Duchy of Perugia within it also served to separate the Lombard kingdom from the Lombard duchies of Spoleto and Benevento.

In ca. 593, King Agilulf retook Perugia (and executed the traitor Maurice) before marching on Rome. Gregory I paid another enormous bribe to persuade him to withdraw. He then began a diplomatic initiative aimed at securing a wider peace between the Lombards and the Byzantines. The exarch Romanus died in 597, and was replaced by the more amenable Callinicus, who finally agreed a truce with Agilulf in 598. Callinicus broke the truce in 601, but Agilulf defeated him before the walls of Ravenna. He was recalled in 603, when Smaragdus was sent back to Ravenna to replace him. This led to a long period of uneasy peace that nevertheless lasted for more than a century.

Orvieto

The first known bishop of “Urbe vetere” was Bishop Giovanni, who received a stern letter from Pope Gregory I in ca. 590 (Epistle XII):

-

“Agapitus, abbot of the monastery of San Giorgio, informs us that he endures many grievances from your Holiness; and not only in things that might be of service to the monastery in time of need, but that you even prohibit the celebration of masses in the said monastery, and also that you interdict burial of the dead there. If this is so, we exhort you to desist from such inhumanity and allow the dead to be buried and masses to be celebrated there without any further opposition, lest the aforesaid venerable Agapitus should be compelled to complain again concerning these matters”.

Candidus appears in the papal registers shortly thereafter:

-

✴as bishop of “Urbe vetere” in 591.

-

✴as bishop of “civitas Bulsinensis” in 595, when he attended the synod in Rome held by Gregory I; and

-

✴as bishop of “Urbe veteri maior” in 596.

It seems therefore that the originally separate dioceses merged at about this time.

In 596 AD, the Lombard King Agilulf (590-616) took advantage of the papal weakness and incorporated Orvieto into his kingdom as part of the Duchy of Tuscany.

Records in the Dialogues relevant to Orvieto are:

-

✴Book I, Chapters 11-2 SS Severus and Martirius of Orvieto

-

✴Book III, Chapter 5 St Sabinus of Canosa, whose relics were venerated at Orvieto

Spoleto

Letters from Gregory I to Bishop Chrysanthus of Spoleto suggest that, while the bishop was well established in the city despite its occupation by the Arian Lombards, the diocesan structure within the Duchy had disintegrated:

-

✴In 597, Gregory I asked Bishop Chrysanthus to assume responsibility for the formerly separate diocese of Bevagna.

-

✴In 603, Gregory I asked Bishop Chrysanthus to discipline the priests of Norcia, which probably did not have a bishop at this time.

Tradition has it that Chrysanthus also administered the vacant dioceses Spello and Trevi, although there is no surviving documentary evidence of this.

Records in the Dialogues relevant to Spoleto are:

-

✴Book III, Chapter 14 St Isaac and the foundation of San Giuliano

-

✴Book III, Chapters 21 Eleutherius, Abbot of San Marco and a pious nun

-

✴Book III, Chapter 29 How an Arian bishop was blinded at San Paolo inter Vineas

-

✴Book III, Chapter 33 Eleutherius, Abbot of San Marco

Norcia

As noted above, Gregory I asked Bishop Chrysanthus to discipline the priests of Norcia in 603, which suggests that the city did not have a bishop at this time.

Records in the Dialogues relevant to Spoleto are:

-

✴Book III, Chapter 15 SS Eutychius and Florentius of Norcia

-

✴Book III, Chapter 37 St Sanctulus, a priest at Norcia

-

✴Book IV, Chapter 10 St Spes of Norcia

-

✴Book IV, Chapter 11 Ursinus, a priest at Norcia

Otricoli

Bishop Domenico of Otricoli was recorded at synods held in Rome by Pope Gregory I in 595 and 601.

St Fulgentius, Bishop of Otricoli at the time of Totila, appears in the Dialogues in Book III, Chapter 12

Narni

Two bishops are known in this period:

-

✴Prejecto (Praeiecticius; Preiectizio), who received a letter from Gregory I in 591 complaining of a pagan presence in his diocese; and

-

✴Costantinus, who attended the synod held in Rome by Pope Gregory I in 595, and who seems to have been appointed as visitor to the diocese of Terni in 598.

St Cassius, Bishop of Narni in 536-58, appears in two accounts in the Dialogues: Book III, Chapter 6 ; and Book IV, Chapter 56.

Gubbio and Gualdo Tadino

In 599, Gregory I put the diocese of Tadinum (Gualdo Tadino) under the care of Bishop Gaudiosus of Gubbio: this diocese had been without a bishop since it had been seized by the Lombard Duke Ariulf of Spoleto in 591, but the situation had improved to the extent that Gregory I could ask Gaudiosus to preside over the election of a new bishop for it.

Other Umbrian Cities in the Dialogues

Gregory I included other references relevant to Umbria in his dialogues: Book I, Chapter 10 St Fortunatus of Todi

-

✴Book III, Chapter 13; St Herculanus of Perugia (reputed to have been Bishop of Perugia at the time of Totila)

-

✴Book III, Chapter 35; St Floridus of Città di Castello (“Tivoli”), who was Bishop of Città di Castello in ca. 593 and also the source for the accounts of:

-

-St Herculanus (above); and

-

-St Amantius (deacon of St Floridus).

Duchy of Spoleto in the 7th Century

When Ariulf died in 601, there followed the relatively uneventful (or at least undocumented) reigns of:

-

✴Duke Teudelapius (601 - 53), the son of the former Faroald I, who emerged after a contest for power with his brother;

-

✴Duke Atto (653 - 63); and

-

✴Duke Transamund I (663 - 703), whom King Grimuald, the former Duke of Benevento, appointed after he took the Lombard crown in a coup in 662.

Pope Martin I (649-54) and the Monothelite Heresy

Martin I was born in what is now Pian di San Martino, outside Todi, but nothing is known about him before he began his career in Rome. He was elected to the papacy without the formal approval of the Emperor Constans II, who duly declared his election invalid. One of his first acts after his election was to convene the Lateran Council (649) in Rome. Its purpose was to condemn Monothelitism, the last of the great Christological heresies, which advanced by three eastern patriarchs: Sergius of Constantinople, Cyrus of Alexandria, and Athanasius of Antioch.

The strong position taken by Martin I brought him into conflict with Constans II, who ordered his arrest. The support of his colleagues in Rome saved him initially. However, in 653, Constans II ordered the new Exarch of Ravenna to arrest and depose him, and to send him to Byzantium. He was humiliated, imprisoned and condemned to death, a sentence that was commuted to exile in the Crimea. Martin I was dismayed when his colleagues in Rome elected another pope (Eugenius I) in May 654. He died on 16th September 655, apparently as a direct result of his harsh treatment.

After the death of Constans II in 668, the new Emperor Constantine IV was inclined to repair his relations with Rome, and this inclination increased after he was forced to face a Muslim siege of Constantinople in 678. He therefore invited Pope Agatho (678 -81) to send delegates to an ecumenical council to be held at Constantinople. By way of preparation, Agatho convened a synod that met Rome at Easter 680. This unsurprisingly condemned Monothelitism, and a report of this condemnation accompanied the western delegates to the the western delegates to the Council of Constantinople (680-1). This Council almost unanimously condemned Monothelitism, and the controversy was at an end.

Lateran Council (649)

The bishops attending included:

-

✴Adeodato of Amelia

-

✴Aquilino of Assisi

-

✴Marciano of Bevagna

-

✴Luminoso, Città di Castello

-

✴Anastasio of Narni

-

✴Lorenzo of Perugia

-

✴Adeodato of Spoleto

-

✴Lorenzo of Todi

Council of Rome (680)

The bishops attending included:

-

✴Teodoro of Amelia

-

✴Florus of Foligno

-

✴Decentius of Forum Flaminii

-

✴Deusdedito of Narni

-

✴Giovanni of Norcia

-

✴Agnellus of Orvieto (Agnellus Vulsiniensis)

-

✴Benedetto of Perugia

-

✴Felice of Spoleto

-

✴Bonifacio of Todi

Duke Faroald II (ca. 703-20)

The religious situation improved over the course of the 7th century as the Lombard nobility was assimilated into the local culture. In particular, Duke Faroald II seems to have been a devout and orthodox Christian:

-

✴In 705, he aided the restoration of the Abbazia di Farfa, an important abbey in the Sabine hills that was at that time within the duchy. Pope John VII granted it important privileges in a letter that referred to Faroald as his "glorious son".

-

✴He apparently became a monk at the Abbazia di San Pietro in Valle (possibly founded by Duke Faroald I - see above) when his son, Duke Transamund II deposed him in 72o (see below).

The political situation however deteriorated as Byzantine authority in Italy crumbled. In 717, Duke Faroald took Classe, although King Liutprand (see below) forced him to return it to the Exarch. In 717, he seized Imperial Narni as part of a wave of unrest. His reluctance to press further may account for his deposition in ca. 720.

King Liutprand (714-41)

King Liutprand (712-44) was the first Catholic king of the Lombards. His law codes, issued in the period 713-35 acknowledged the primacy of the papacy in religious affairs. Nevertheless, his success in uniting much of Italy under his rule frequently brought him into conflict with the papacy, as well as with the independent dukes of Spoleto and Benevento.

King Liutprand’s territorial ambitions were helped by the deterioration in the relations between Pope Gregory II (715-31) and the Byzantine Emperor Leo III (717-41). The initial cause was the high level of imperial taxes. The Exarch Paul sent an army against Rome to enforce his demands in ca. 723, but Duke Transamund II of Spoleto blocked his way and he was forced to withdraw.

It is unlikely that King Liutprand was pleased by this display of independence on the part of Transamund II.

Imperial-papal relations became much worse in 726, when Leo III issued a decree that prohibited the use and display of icons, a move that led to an Italian revolt. From this point, the Duchy of Perugia came effectively under the direct control of the papacy and, together with the Duchy of Rome, formed the kernel of the emerging Papal States.

In 727, King Liutprand used this opportunity to march on Ravenna. He crossed the Po and took a number of imperial cities in Emilia and the Romagna, including Classe. However, he could not take Ravenna itself.

A mob killed the Exarch Paul there soon after.

In 729, King Liutprand somewhat opportunistically made an agreement with Paul’s successor, Eutychius, to the effect that they would depose Gregory II and end the independence of the Duchies of Spoleto and Benevento. In fact, the respective dukes, Transamund II and Godescalc, surrendered to King Liutprand and swore loyalty to him soon after, removing his need for the deal. He duly marched on Rome but met with Gregory II at Sutri and reached an understanding with him. He also brokered a reconciliation between Gregory II and Eutychius.

It seems that King Liutprand believed that he could now replace the hated Leo III as the secular head of the Catholic Church in the west:

-

✴His peace with Gregory II involved the so-called Donation of Sutri, by which Sutri itself and some hill towns in Latium passed to the papacy: this first extension of papal territory beyond the confines of the Duchy of Rome marked the beginning of the Papal States.

-

✴When he entered Rome, he deposited his royal insignia on the tomb of St Peter in a token of acknowledgement of the spiritual supremacy of the papacy.

-

✴He also prayed before an icon of St Anastasius the Persian that had come to symbolise western resistance to iconclasm. He claimed to have had a vision there, following which he built a church dedicated to St Anastasius at Cortelona, near Pavia. In the inscription that commemorated this event, he prayed to Christ that “the Catholic order might grow with me”.

Unfortunately for King Liutprand’s aspirations, Gregory II died in 731.

In 738, Duke Transamund II tried to re-assert his independence from King Liutprand and this heralded a period of great instability in Spoleto:

-

✴King Liutprand took the Duchy in 739 and installed Duke Hilderic there.

-

✴Transamund II fled to Rome and the protection of Pope Gregory III.

-

✴Liutprand marched on Rome, taking a number of others cities, including Amelia, on the way.

-

✴Gregory III sent an embassy to Charles Martel, the effective ruler of the Franks, and he in turn sent back his own embassy to mediate between the warring parties.

-

✴Gregory III helped Transamund II to regain the Duchy of Spoleto in 740 and to depose Duke Hilderic.

-

✴Transamund II however refused to honour his promise to retake the cities that King Liutprand had captured and to return them to the papacy. Indeed, he prepared to march on Rome.

At this moment, Gregory III died and his successor, Pope Zacharias forged an alliance with King Liutprand. With papal help, King Liutprand retook the Duchy of Spoleto in 742 and installed his own nephew, Agiprand, as duke.

Like Duke Transamund II before him, King Liutprand was reluctant to honour the promises that he had made. Zacharias therefore proposed a meeting. According to the “Liber Ponificalis”, they met “ad basilicam beati Valentini episcopi et martyris sitam in praedicta Teramnensium urbe ducatus Spolitini” (near the basilica of the Blessed Valentine, bishop and martyr, in the previously mentioned Terni, city of the Duchy of Spoleto) in 742. (This is the first mention of the existence of the basilica and the only source for the information that Terni was within the Duchy of Spoleto at this time). King Liutprand agreed to return a number of cities (including Amelia and the other three cities that had been recently disputed, along with other territories, including Narni) to the papacy and to a truce of 20 years. The restitutions of the territories in question was made to “beato Petro apostolorum principi” (blessed Peter, first of the Apostles). Thus, Zacharius regained the property for the papacy, independently of any other temporal authority.

During the mass at San Valentino after this agreement, Zacharius agreed to a request from Liutprand that he should ordain a bishop for a town in the Lombard territory, the identity of which is unclear. A convivial celebration followed, and Liutprand “did not remember when he had eaten so much and so pleasantly”. Zacharius collected the keys of three of the returned cities (Amelia, Orte and Bomarzo). he was then granted safe conduct across Lombard territory to avoid a circuitous journey to the fourth of the returned cities, Bieda, some thirty miles from Rome.

[Bishop Gregorius of Orvieto attended the council that Pope Zacharias held in Rome in 743.]

King Aistulf (749-56)

King Liutprand died in 744. His immediate successor, King Ratchis did not oppose the independence of the Duchy of Spoleto. Duke Transamund II was able to regain his position there in ca. 744 and hold it until he died in 745. However, he was to be the last independent Duke of Spoleto.

King Ratchis besieged the city in 749 but Pope Zacharias was able to persuade him to relent.

King Aistulf (who had deposed his brother, Ratchis) captured Ravenna in 752 and threatened Rome. This prompted Pope Stephen II to despair of the Byzantine Emperor and to turn instead to King Pepin III of the Franks. He could expect a good reception because his predecessor, Pope Zacharias, had allowed his legate to anoint Pepin III only two years before, thereby legitimising what had really been a usurpation of power.

In 753, Stephen II became the first pope to cross the Alps and was graciously received at Ponthion by Pepin III. At a second meeting in 754 Stephen II received the “Donation of Pepin”, by which Pepin III guaranteed papal possession of Rome, Ravenna, the Exarchate and large tracts of land that was still in Lombard occupation. (The document is lost and the precise territorial extent of this “donation” is unclear). Pepin had yet to acquire control of these territories: the papal claim on them laid the foundation for the establishment of the Papal States. In return, Stephen III re-anointed Pepin III in person.

Pepin III duly crossed the Alps in 754 and easily defeated King Aistulf, who was forced to swear to hand over to Stephen III the lands that he had recently conquered. When Pepin III returned to Francia, King Aistulf reneged on his promises, seized Narni and laid siege to Rome. Pepin III returned to Italy in 756, by which time Aistulf had abandoned the siege and returned to Pavia. Again he was defeated and again he managed to hang on to his crown. We will never know whether Aistulf would have honoured his promises this time because he was killed in a riding accident almost as soon as Pepin III returned to Francia.

Before he left Italy, Pepin formally acknowledged papal sovereignty over the land that had belonged to the Exarchate of Ravenna, a donation that was to form the basis of the Papal States. The relevant documentation has been lost, but it seems from later confirmations of the donation that it included the following Umbrian cities: Amelia; Gubbio; Narni; Otricoli; Perugia; and Todi.

King Desiderius (756-74)

When King Aistulf died in 756, his brother, King Ratchis resumed the throne and the nobles of the Duchy of Spoleto asserted their independence under a new duke, Alboin, apparently with the agreement of the new Pope Stephen II and King Pepin. However, his rule was to be short-lived. Stephen II miscalculated by backing a coup that deposed King Ratchis in favour of King Desiderius in return for a promise that Desiderius would transfer Imola, Osimo, Ancona, and Bologna to the papacy. When Stephen II died in 757, his brother succeeded him as Pope Paul I.

Desiderius soon showed his metal by marching south and taking the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento in 758. Paul I complained to Pepin that he had failed to deliver the cities that he had promised to the papacy, and that he had devastated the Pentapolis on this expedition against Spoleto and Benevento. After his success at Benevento, Desiderius travelled to Naples, where he secured a promise of help from George, the representative of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine V, to help him to capture the fugitive Duke of Benevento in return for his assistance with a Byzantine invasion of Ravenna (then in papal hands).

Desiderius then met with and threatened Paul I at Rome. The frightened pope managed to get an appeal through to Pepin, who sent two envoys (his brother, Bishop Remidius of Rouen and Duke Authar) to Desiderius in early 760. Pepin was keen to undermine the alliance between Desiderius and the Byzantines, so his envoys acted diplomatically and succeeded in negotiating an uneasy compromise between Desiderius and Paul I: Desiderius kept the disputed cities but refrained from prejudicing the papal hold over Ravenna.

Paul I could now concentrate on his dispute with Constantine V in relation to his iconoclasm. Constantine had summoned the Council of Hieria in 757, at which the veneration of icons was anathematised. Paul I made the monastery of SS Stefano e Silvestro, which he had established in his home in Rome in 761, available to monks from the east fleeing persecution. He secured the support of Pepin agains iconoclasm in 767.

The position in Italy was now in a state of equilibrium. However, Desiderius’ position was transformed by the death of Paul I later in 767 and that of Pepin in 768.

Read more:

T. Noble, “The Republic of St Peter: the Birth of the Papal State (680-825)”, (1986) Pennsylvania

R. Poole, “The Chronology of Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica and the Councils of 679-680”, Journal of Theological Studies, 20 (1919) 24-40

Return to the page on the History of Umbria.

Continue to the page on Umbria under Charlemagne.