Census of 318 BC

It seems that the Caudine Peace of 318 BC left space for the Romans to continue with the consolidation of their earlier expansion. The fasti Capitolini recorded that:

-

✴the censors of 332 BC (Spurius Postumus Albinus and Quintus Philo Publilius) completed the 24th lustrum; and

-

✴those of 318 BC (Lucius Papirius Crassus and Caius Maenius) completed the 25th lustrum.

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 268) pointed out that there is fragmentary evidence for the appointment of censors in 319 BC, but they seem to have abdicated before the completion of their term. In other words, the census of 318 BC was probably only the second to be completed since the end of the Latin War.

The census of 332 BC (discussed on the previous page) seems to have been largely concerned with the formalisation of the settlement in Latium after the Latin War (albeit that, according to Velleius Patroculus, the censors of 332 BC, were responsible for the incorporation of Campanian Acerrae). Now that relations with the Samnites were quiescent, the Romans could address the consolidation of the territory outside Latium that they had acquired during and after this earlier war.

Livy did not refer directly to the census that took place in 318 BC, but he recorded that, in this year:

-

“At Rome, two tribes were added, the Oufentina and the Falerna”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 20: 6).

Diodorus Siculus also noted that, in this year, the Romans:

-

“... added two new tribes to those already existing: Falerna and Oufentina”, (‘Library of History’, 19: 10: 2).

These were the first new tribes that had been created since 332 BC, when (in the census of that year) the Maecia and the Scaptia had been created for new citizens in Latium.

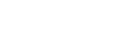

Oufentina

Adapted from G. Tol et al. (referenced below) p. 114, Figure 1)

According to Festus:

“Oufentinae tribus initio causa fuit nomen fluminis Ofens, quod est in agro Privernate mare intra et Terracinam”, (‘de verborum significatu’, 212, Lindsay)

“The Oufentina was named for the Ufens river, which is in the ager Privernus,

between the sea and Tarracina” (my translation)

According to Strabo:

-

“In front of Tarracina lies a great marsh that is formed by two rivers, the larger of which is called Aufidus. It is here that Via Appia [see below] first touches the sea”, (‘Geography’, 5: 3: 6).

According to Duane Roller (referenced below, at p. 251):

-

“[Strabo’s] Aufidus is probably the Ufens (modern Uffente), which flows down the east side of the Pomptine plain, with its mouth just west of Taracina.”

Given the context, the other river must have been the Amasenus (modern Amaseno).

As Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 268) pointed out:

-

“[The Oufentina] must have been established on land confiscated from Privernum, whose territory was thereby restricted to the Amaseno valley and its surroundings.”

It is not clear whether this land was confiscated in 340 or in 329 BC. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 393) observed that creation at the latter date would explain why the Oufentina was created in the census of 318 rather than in that of 332 BC, although he pointed out (at p. 394, note 1) that:

-

“... the matter cannot be decided beyond all doubt.”

In either event, it seems likely that the land of the senators who were exiled in 329 BC would also have become available for citizen settlement at this point.

Centres underlined in blue (Privernum; Tarracina,; Frusino ?; and Aquinum) = Oufentina

As Heikki Solin (referenced below, at p. 78) pointed out,

-

“The Oufentina was [eventually] the tribe of citizens of [the following centres in] Regio I: Aquinum; [possibly] Frusino; Privernum; and Tarracina” (my translation).

(For the uncertainty about the assignation of Frusino, see his note 1 at p. 71).

-

✴It seems likely that the Oufentina was created for the viritane settlers on the land that had been confiscated from Privernum in 340 and/0r 329 BC.

-

✴As discussed on the previous page, 300 citizens were enrolled in a new colony at Tarracina in 329 BC on land that had been confiscated from Privernum. Its colonists were presumably also re-registered in the Oufentina in 318 BC.

-

✴Viritane citizen settlers on land that was confiscated from Frusino in 303 BC might have re-registered in the Oufentina shortly thereafter.

-

✴When the people of Privernum, Frusino and Aquinum were eventually enfranchised (probably after the Social War), they too were (or, in the case of Frusino, were probably) assigned to the Oufentina.

Falerna

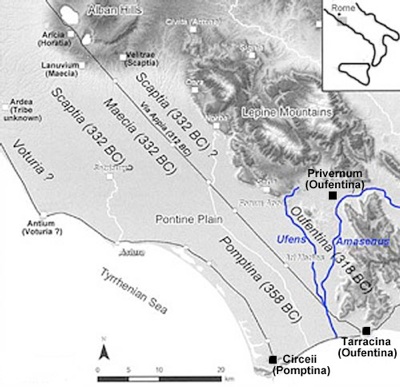

Underlined in blue = assigned to the Falerna tribe

Other tribes: Cumae = Claudia ?; Suessula and Casilinum = unknown tribe (if any)

See G. Camodeca (referenced below) for these tribal assignations

Red asterisks (Volturnum; Liternum; Puteoli; and Salernum) = citizen colonies founded in 194 BC

Underlined in green = Campanian prefectures (see below)

Adapted from this map on the webpage on Roman Campania by Jeff Matthews

According to Festus:

“Falerina tribus ab agro Falerno in Campania”, (‘de verborum significatu’, ??? Lindsay)

“The Falerna tribe is named for the ager Falernus in Campania” (my translation)

There is little doubt that this was the land north of the Volturnus that the Romans had confiscated from Capua in 340 BC. Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, at pp. 301-2, entry 5) suggested that this territory had been confiscated in its entirety and (at note 20) that, since:

-

“There is no record of the later distribution of land in the area, .. the whole ager Falernus seems to have been distributed in its entirety [at the time of its confiscation].”

However, as noted on the previous page, the 1,600 Campanian knights who had remained loyal to Rome during the Latin revolt had received citizenship and had been exempted from this confiscation:

-

✴We might reasonably assume that the Falerna was created for the re-registration of the ‘old’ citizens who had been settled on the remaining land here during the 22 years since its confiscation.

-

✴According to Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 160, note 3):

-

“There is no evidence for t[he tribe to which the 1,600 knights of Capua who had been fully incorporated into the Roman state in 340 BC were registered], but it may have been the Falerna ...”

-

It seems to me that, since they had retained their land in the ager Falernus in 340 BC, this putative assignation to the Falerna is almost certain.

-

✴According to Giuseppe Camodeca (referenced below), a single inscription suggests that the citizens of Forum Popillii in the ager Falernus, which was presumably a Roman foundation, were assigned to the Falerna.

As with the Oufentina, we might wonder why the Romans waited so long to create the Falerna for settlers on land that had been confiscated in 340 BC. However, new tribes were always added in even numbers (to preserve the total as an odd number, thereby avoiding tied elections), and it might be that the delay related to the situation in the ager Privernus, rather than that in the ager Falernus.

As discussed on the previous page, Capua was incorporated sine suffragio in 338 or (more probably) 334 BC. Despite this, it revolted against Rome in 216 BC, during the Hannibalic War and (as we shall see) suffered the confiscation of the entire ager Campanus. Two citizen colonies (Voltumnum and Liternum) were founded on coastal sites here in 194 BC, along with two others on the coast of Campania (Puteoli, the port of Cumae; and Salernum): the citizen colonists at all four were (or, in the cases of Liturnum and Salernum, were probably) assigned to the Falerna. The case of Capua itself is more complex: according to Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 160, note 3):

-

“The ager Campanus [remained as] public land until 59 BC, and was not assigned to a tribe. ... Capua [itself] was assigned to [the Falerna] when it was colonised by [Julius Caesar in 59 BC].

When the majority of the people of Campania were eventually enfranchised after the Social War, a number of them, including those of Calatia, Atella, Suessula and Nola, were assigned to the Falerna: however, according to Giuseppe Camodeca (referenced below), there is no surviving epigraphic evidence for the Falerna at Cumae, and some for its assignation to the ancient Claudia tribe.

Roman Laws at Capua and Antium (318 BC ?)

Capua

According to Livy:

-

“... praefecti (Roman prefects) began to be appointed for Capua after legibus ab L. Furio praetore datis (the praetor Lucius Furius had given/ imposed laws) on the Campani. The Campani themselves had asked for both [the appointment of a prefect and the imposition of Roman laws], as a remedy for the distress occasioned by internal discord”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 20: 5-6).

In this translation, I have attempted to reflect the comments of Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at pp. 266-7) and Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 61). Both of these authors cited Jerzy Linderski (referenced below, 1979, at p. 248, note 5), who summarised the situation as follows:

-

“The Capuans asked the Romans to provide them with [laws] and to send prefects for the administration of justice. ... It is obvious that a praetor could [neither give laws to anyone nor] send out the prefects without being authorised to do so by the Senate or the [Roman] people.”

This arrangement seems to have been an administrative innovation: according to Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p.61_:

-

“The early appearances of the praetor in Livy are [all]:

-

✴outside Rome; [and]

-

✴in a military capacity ... .

-

When we do see the praetor acting in [Rome itself] ... he is doing practically everything accorded to him by virtue of his imperium except hearing cases at law. ... In one case, we we do see him in a law-making context, but [this case concerns] Capua ....”

This case is also the first time that Livy mentioned dispatch of Roman prefects (presumably as delegates of the praetor) to administer justice in out-lying districts that were under Roman jurisdiction.

Degree of Administrative Independence at Capua (340 - 211 BC)

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at pp. 556-7) pointed out that, at the time that Capua defected to Hannibal in 216 BC, it clearly enjoyed substantial independence from Rome. For example, Livy recorded that, on the eve of this revolt, the consul Caius Terentius Varro reminded the Campani that:

-

“... after you surrendered [to Rome in 340 BC], we:

-

✴gave you a treaty on equal terms;

-

✴allowed you to retain your own laws; and ...

-

✴granted our citizenship to most of you; and

-

✴made you members of our commonwealth”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 5: 5).

There is also other evidence that Capua retained its pre-Roman magistracies up to that point:

-

✴According to Livy, by 216 BC

-

“... Pacuvius Calavius held the senate of Capua entirely in his power ... He happened to be in summo magistratu (the chief magistrate at Capua) in the year in which [Hannibal defeated the Romans at Lake Trasimene (i.e., in 218 BC)] ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 23: 2: 3).

-

✴In 216 BC, we find Marius Blossius, as praetorem Campanum, dealing directly with Hannibal (‘History of Rome’, 23: 7: 8).

-

✴In 215 BC, we find Marius Alfius, the medix tuticus, presiding over a local ritual at Hamae, near Cumae. Livy gave him his Oscan title here, and then explained that this was the title of the chief Campanian magistrate (‘History of Rome’, 23: 35: 13).

Michael Fronda and François Gauthier (referenced below, at pp. 317-8 and note 37) noted that, despite the variety of terms that Livy used in these passages, all three magistrates were Campanian medices. Furthermore, Livy referred to four other medices (two of whom were unnamed) before this final Campanian revolt ended in 211 BC. Only then did Capua lose its independence: according to Livy, some 370 prominent Campani were executed:

-

“... and the remaining mass of citizens were sold [into slavery]. ... The whole [of the ager Campanus] ... became public property of the Roman people. While Capua survived as a nominal city, ... it was decided that it should have no political body (neither senate nor council of the plebs) and no magistrates. ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 26: 16: 6-10).

Thus, we can reasonably assume that Capua also retained its own laws until 211 BC. If so, we need to consider how the laws that Lucius Furius imposed on the Campani in 318 BC sat alongside Campanian law. However, before addressing this question, we need to consider more fully what kind of laws those imposed by Furius might have been.

Nature of the Leges Datae of 318 BC

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 267) argued that the expression ‘legibus a ... praetore datis ’ used in the passage above is:

-

“... a general expression for the imposition of a law, [rather than] a technical term. Nevertheless, it is ... often found in the context of a Roman magistrate arranging the affairs of a community under Rome’s jurisdiction ...”

He cited a number of examples of this type of arrangement, all of which came from part of speech (‘in Verrem’, 2: 2) that Cicero delivered in his prosecution Caius Verres, the erstwhile governor of the province of Sicily, in 70 BC. Verres was charged with (inter alia) using bribery to subvert the rule of law in Sicily, and the material that Cicero presented in court in this part of his speech throws light on the way in which Roman law supplemented traditional Sicilian law at this time.

Oakley’s first example related to the so-called leges Rupiliae, which were named for Publius Rupilius, who was consul and then proconsul in Sicily at the time of the First Sicilian Slave War (132-131 BC). As Oakley pointed out, Cicero’s phrase:

‘legem esse Rupiliam, quam P. Rupilius consul ... dedisset’ (2: 2: 39)

the lex Rupilia, which Publius Rupilius had given/imposed

is very similar to that used by Livy in the passage under discussion here. Jonathan Prag (referenced below, at p. 170) argued that laws of this kind:

-

“... were not statute laws of the Roman people, but leges datae from an individual magistrate in the field, which in turn came to be maintained and enshrined within the edicts of subsequent governors of Sicily, at their individual discretion, but at the injunction of the original senatus consultum.”

Cicero also claimed that, before Verres became governor:

-

“... everyone had most strictly observed the leges Rupiliae on all points, and especially in judicial matters (2: 2: 40).

From this, it is clear that Rupilius had given the province of Sicily a number of laws, only some of which involved judicial matters.

Cicero threw further light on only one of Rupilius’ laws:

-

“If a Sicilian has a dispute with another Sicilian from a different city, then the praetor is to assign judges of that dispute according to the law of Publius Rupilius, which ... the Sicilians call the lex Rupilia”, (2: 2: 32).

From the context of this last remark, we know that this lex Rupilia operated along other Sicilian laws:

-

✴disputes between Sicilians of the same city were decided “according to the laws there existing”;

-

✴in disputes between Sicilians from different cities, the judge was selected in accordance with a lex Rupilia;

-

✴disputes between a Sicilian and his own community were decided by the arbitration of another city;

-

✴a Sicilian judge was assigned in cases in which a Roman citizen made a claim against a Sicilian;

-

✴a Roman citizen was appointed to judge cases in which a Sicilian made a claim against a Roman citizen;

-

✴‘in all other matters’, judges were appointed from among the Roman citizens who lived in the relevant community; and

-

✴in cases between the farmers and the tax collectors, trials were regulated by the ‘law about corn’ that was known as the Lex Hieronica (which was probably named for Hiero II, the tyrant of Syracuse in 270 - 215 BC)

Oakley’s other examples from in Verrem are more directly relevant to the case of Capua, because they related to leges datae at individual Sicilian cites. As Jonathan Prag (referenced below, at pp. 170-1) pointed out, Cicero described three such laws in this speech, which related to the cities of:

-

“...Agrigentum, Halaesa and Heraclea, and [which] were composed by, respectively:

-

✴an unidentified Scipio (some time in the 2nd century BC?);

-

✴Caius Claudius Pulcher, the praetor de repetundis of 95 BC; and

-

✴Publius Rupilius [whose provincial legislation was discussed above].”

In fact, we can identify the ‘Scipio’ who gave laws to Agrigentum, because Cicero referred to him again in a passage (2: 2: 86-7) that clearly related to the activities of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus in Sicily immediately after the fall of Carthage in 146 BC: this passage is translated in the website of ‘Attalus’, alongside a confirming inscription. We might therefore reasonably assume that the Scipio associated with the leges datae at Agrigentium was Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, and that this law was given in or shortly after 146 BC.

Taking these three site-specific leges datae in chronological order:

-

✴Agrigentum:

-

“The people of Agrigentum have old laws about appointing their senate, given to them [in ca. 146 BC by Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus], in which the same principles [as those of the law of Claudius Pulcher at Halaesa - see below] are laid down. [However], there are two classes of citizens of Agrigentum:

-

✴one class made up of the old inhabitants; and

-

✴the other made up of the new settlers whom Titus Manlius, when praetor [in 197 BC], had led from other Sicilian towns to [a new colony at] Agrigentum, in obedience to a resolution of the Senate.

-

[For this reason], the laws of Scipio [contained a provision that was not subsequently needed at Halaesa]: that the number of senators drawn from the [colonists of 197 BC] should not exceed the number drawn from the old inhabitants of Agrigentum”, (2: 2: 123).

-

✴Heraclea:

-

“Publius Rupilius [as proconsul in 131 BC] had led settlers [to Heraclea] and legesque similis ... dedisset (had given them similar laws) [to those that Scipio had given to Agrigentum] that dealt with:

-

✴the appointment of the senate; and

-

✴the [proportions] of the old and new senators”, (2: 2: 125).

-

✴Halaesa:

-

“The citizens of Halaesa had long retained their own laws, in return for [their loyalty and that of] their ancestors to our Republic. [However], in the consulship of Lucius Licinius Crassus and Quintus Mucius Scaevola Pontifex [i.e., in 95 BC], they requested laws from our Senate, as they had disputes among themselves about the elections into their senate. Our Senate ... voted that Caius Claudius Pulcher, the son of Appius the praetor, should draw up regulations for the elections to their senate. [He duly] gave laws to the men of Halaesa (leges Halaesinis dedit) ... in which he laid down many rules relating to: the age of the men who might be elected (no one might be under 30 years of age); trade (those engaged in it were ineligible); [the minimum required] income; and all other matters”, ( 2: 2: 122).

Jonathan Prag (as above) pointed out that Cicero used these three examples because they related to:

-

“... the principal occasions on which Verres’ interference in local civic arrangements could be presented as most unreasonable [to Roman eyes, because these cities had all] ... received specific charters from imperium-holding Roman magistrates, backed by the Roman Senate.”

This is clearest in Cicero’s charge that Verres had ignored:

-

“... not only the laws of the Sicilians, but even those that had been given to them by the Senate and the People of Rome: for the laws made by those:

-

✴whose supreme command had been given to them by the Roman people: and

-

✴whose authority to make laws had been conferred on them by the Senate;

-

ought to be considered the laws of the Senate and People of Rome”, (2: 2: 122).

The most interesting things about these three leges datae for our present purpose are that:

-

✴they all relate to the election of local senators;

-

✴at the colonies of Agrigentum and Heraclea, they regulated (inter alia) the proportion of ‘old’ and ‘new’ inhabitants who could be elected at any one time; and

-

✴at Halaesa, the people (however defined) asked for leges datae to replace existing local laws that (for whatever reason) had become the subject of contention.

This body of evidence from ‘in Verrum’ contains most of what we know about leges datae. It seems to me that we might hypothesise about its content on the basis of the following facts:

-

✴Livy identified seven cities that had been incorporated sine suffragio since 338 BC (Capua, Cumae, Suessula, Acerrae, Privernum, Fundi and Formiae), but only one that received leges datae (Capua, in 318 BC). Thus, it seems unlikely that a law of this kind was needed to supplement other legislation (presumably bilateral treaties and/ or municipal charters) that regulated the new relationships of the civitates sine suffragio with Rome.

-

✴In particular, although Livy noted the creation of the Falerna and the Oufentina tribes in 318 BC, which indicate that there was a significant level of citizen settlement on land that had been confiscated from (respectively) Capua and Privernum, he did not record leges datae at Privernum.

-

•It is possible that hostility between the citizen settlers in the ager Falernus and the native Campani caused the settlers to ask for the laws that Lucius Furius imposed on Capua. If so, then they would probably have related to legal disputes between the native Campani and the recent settlers from Rome.

-

•However, it is difficult to imagine why relations between the native Privernates and the recent settlers from Rome in its erstwhile territory should have been less hostile.

-

✴There is one way in which Capua can be distinguished from all of the other six new civitates sine suffragio, including Privernum: 1,600 Campanian knights had received full citizenship in 340 BC. This might well have prompted a lively debate about:

-

•whether local or Roman law applied to the enfranchised Campani;

-

•how legal disputes between enfranchised and un-enfranchised Campani were to be resolved; and

-

•the proportions in which enfranchised and un-enfranchised Campani could be elected to the local senate at any one time.

-

It seems to me that the most likely scenario is that the enfranchised Campani asked for the laws that Lucius Furius imposed on Capua, and that it dealt with matters like these.

The Practice of Sending Roman Prefects to Capua

As noted above, Livy recorded that, in 318 BC:

-

“... praefecti (prefects) began to be appointed for Capua ... as [part of] a remedy for the distress occasioned by internal discord”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 20: 5-6).

As noted above, this is the first time that Livy mentioned dispatch of Roman prefects (presumably as delegates of the urban praetor) to administer justice in out-lying districts under Roman jurisdiction.

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at pp. 555-6) pointed out that Livy:

-

“... need not imply that prefects were sent to Capua every year [from this point]: rather, [in this year] Capua had appealed to Rome, and the praetor consequently passed some laws, [after which] a prefect was dispatched to apply them.”

Oakley was making two suggestions here:

-

✴that the first prefects sent to Capua wer sent specifically and solely for the purpose of applying the leges datae and thereby remedying the internal conflict there; and

-

✴that Livy’s phrasing does not imply that the sending of prefects was a regular occurrence thereafter. In his opinion (see Oakley, 1998, at p. 556):

-

“How often prefects went to Capua after 318 BC we simply cannot say."

It seems to me that Oakley’s first suggestion needs further consideration.

In the section above, I suggested that:

-

✴it was probably the enfranchised Campanian knights who asked the Romans for the imposition of leges datae on Capua in 318 BC; and

-

✴this body of Roman law probably addressed matters such as:

-

•whether local or Roman law applied to the enfranchised Campani;

-

•how legal disputes between enfranchised and un-enfranchised Campani were resolved; and

-

•the proportions in which enfranchised and un-enfranchised Campani could be elected to the local senate at any one time.

If this is correct, then the likelihood is that, after its imposition, Roman law would have governed disputes:

-

✴between enfranchised Campani; and

-

✴(probably) between enfranchised and un-enfranchised Campani.

Although Capua still had its own magistrates, they could hardly have been tasked with the application of Roman law, not least because at least some of them would not have been proficient in Latin. In other words, I think that, from this point, Roman prefects were probably sent regularly (perhaps annually) to Capua for the purpose of administering the legal affairs of enfranchised Campani.

Date of these Legislative Innovations at Capua

As noted above, Livy asserted that, in 318 BC,

-

✴the people of Capua asked the Romans to:

-

•provide them with leges datae; and

-

•begin the practice of sending prefects; and

-

✴that these measures were needed:

-

“... as a remedy for the distress occasioned by internal discord”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 20: 6).

Adrian Sherwin White (referenced below, at p. 43) argued that:

-

“... the leges a praetore datae should have provided a permanent solution of the troubles of the time".

However, as we shall see, the Campani revolted again in 314 BC, in circumstances that suggest that internal discord had by no means ended in 318 BC. It therefore seems to me that it is at least possible (pace Livy) that the legal innovations discussed here were actually made after that rebellion was ended. I discuss this possibility at the end of the section below on the Campanian Revolt (314 BC).

Antium (318 BC ?)

The people of what was then the Volscian city of Antiumhad joined the Latins in ther rebellion agains Rome in 340 - 338 BC. Livy had described the Roman settlement with the Antiates after thier surrender as follows:

-

“... a colony was dispatched to Antium, with an understanding that the Antiates were permitted, if they wished, to enrol as colonists. ... They were granted civitas (citizenship)”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 14: 7-9).

Since Livy recorded that the Antiates received civitas (as opposed to civitas sine suffragio) we might reasonably assume that they were incorporated optimo iure after their final defeat. Thus, after 338 BC, ‘the Antiates’ comprised:

-

✴citizens from Rome who were enrolled in the colony; and

-

✴the people of the Volscian city, all of whom were fully enfranchised, who included:

-

•some who were also enrolled in the colony; and

-

•others who were not.

In 318 BC, according to Livy:

-

“Once it had become known among the allies that the affairs of Capua had been stabilised by Roman discipline, the Antiates, too, complained that they were living without fixed statutes and without magistrates. The Senate designated the colony's own patrons give laws [to them]”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 20: 10).

There has been a debate among scholars as to which ‘Antiates’ had complained that they were in a legal vacuum. However, as Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1998, at p. 566) pointed out, the colony:

-

“... must always have had [at least] some constitution ...”

He therefore argued (at p. 566) that:

-

✴during the twenty years after they received civitas optimo iure, the Antiates who had not enrolled in the colony had no urban settlement to which they might belong; and

-

✴thereafter, the laws drawn up by the patrons of the colony meant that they were regulated from it.

This view now seems to be widely accepted: for example, Jeremia Pelgrom (referenced below, at Chapter 5, p. 179) observed that:

-

“... the consensus now seems to be that the Antiates who were the recipients of a corpus of legal regulations (iura statuenda) from the patrons of the colony were the indigenous people of Antium [who were not colonists].”

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 2005, at p. 275) suggested that the ‘patrons’ who drew up these laws would have been the triumviri coloniae deducendae, the three magistrates who had founded the colony, enrolled its colonists, divided its territory for assignation to the colonists, and given it its laws.

Conclusions: Laws Imposed at Capua and Antium in 318 (?) BC

It is interesting to compare the scenarios suggested above for the imposition of Roman laws at Capua and at Antium:

-

✴Both bodies of law probably applied specifically to anomalous groups of ‘natives’:

-

•the enfranchised Campani at the civitates sine suffragio of Capua; and

-

•those enfranchised Antiates who had chosen not to be enrolled at the citizen colony of Antium.

-

✴Both of these anomalous groups contained only Roman citizens.

-

✴However:

-

•the urban praetor seems to have appointed a prefect to draw up the leges datae given to Capua; while

-

•the triumviri coloniae deducendae were available at Antium to draw up the corpus of legal regulations that applied to those Antiates who were not enrolled in the colony.

If these scenarios are accepted, we can also infer why prefects sent to Capua but not to Antium:

-

✴Roman prefects would have been needed on a regular basis to apply the Roman leges datae at Capua, since the Campanian magistrates there who applied local law would not have been qualified to do so.

-

✴However, there would have been no need for prefects at Antium, since the colony’s existing [and presumably Roman] magistrates who already administered the legal aspects of the colonial charter would have been well-placed to take on the administration of the enfranchised Antiate who were not enrolled in the colony.

I discuss below the possibility that these new measures at Capua and Antium were actually taken after the revolt of the northern Campani in 314-3 BC.

Date of the Leges Datae at Capua (314 BC ?)

As noted above, Livy asserted that, in 318 BC, the people of Capua had asked the Romans to provide them with leges datae (and to begin sending prefects to the city):

-

“... as a remedy for the distress occasioned by internal discord”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 20: 6);

Adrian Sherwin White (referenced below, at p. 43) argued that:

-

“... the leges a praetore datae should have provided a permanent solution of the troubles of the time".

However, when Rome faced a serious threat from the Samnites in 314 BC, a pro-Samnite faction at Capua was still strong enough to foment a pro-Samnite rebellion that might well have been finally ended only in 313 BC:

-

✴There is a danger of applying hindsight here: it is possible that the Romans were sufficiently in control of events in 318 BC to impose these laws, and that the subsequent revolt at Capua took them by surprise.

-

✴However, as discussed above, it is at least possible that these measures followed the revolt of 314-3 BC, at which time the pro-Roman faction at Capua (which would surely have included most of the knights who had been enfranchised in 340 BC) would have been in the ascendancy. In other words, this would have been the ideal time for them to request (and for the Romans grant the) measures that would enshrine their position

In this context, we might look again at how Livy concluded his account of the imposition of the leges datae at Capua:

-

“Once it had become known among the allies that the affairs of Capua had been stabilised by Roman discipline, the Antiates, too, complained that they were living without fixed statutes and without magistrates. The Senate designated the colony's own patrons give laws [to them. Now, not only] Roman arms, but also Roman law, began to exert a widespread influence”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 20: 10).

Thus, it seemed to Livy that, with the imposition of the leges datae at Capua, the way in which Rome controlled the outlying areas under her jurisdiction changed fundamentally. Thus, in my view, it is at least possible that this measure belonged in the period 314-2 BC, in which the Romans:

-

✴defeated the Aurunnci and seized their territory (above);

-

✴suppressed the revolt of the norther Campani; and

-

✴defeated the Campanian city of Nola;

-

✴established or re-established a chain of Latin colonies on the western border of Samnium; and

-

✴built the Via Appia from Rome to Capua, through what was now a continuous tract of territory that was securely within the jurisdiction of Rome.

Census of 312 BC and the Via Appia

Red squares = citizen maritime colonies: Antium (338 BC); Tarracina (329 BC)

Black squares = Latin colonies: Circeii (before 338 BC); Cales (334 BC); Fregellae (328, refounded 313 BC);

Luceria (314 BC); Saticula (313 BC); Suessa Aurunca (313 BC); Pontiae (313 BC); Interamna Lirenas (312 BC)

The fasti Capitolini record that the censors of 312 BC (Appius Claudius and Caius Plautius) completed the 26th lustrum. Livy described the context:

-

“The war with the Samnites was practically ended. ... The year was noteworthy for the censorship of Appius Claudius and Caius Plautius, although Appius’ name was ... [better-remembered] because he built a road, and also brought water into the City. He carried out these undertakings by himself, [after] his colleague had resigned ...”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 29: 6-7).

Michel Humm (referenced below, 1t p. 713, note 42) observed that:

-

“The Roman expansion into Campania and southern Italy in the 2nd half of the 4th century BC and the Samnite threat certainly induced Appius Claudius to build a road that offered a faster and safer alternative to via Latina ...: the road built by Appius Claudius followed the route of an old, coastal road ...”

He also gave the distances from Rome to Capua by each of these roads:

-

✴Via Latina: 147 Roman miles (218 km); and

-

✴Via Appia: 132 Roman miles (196 km).

Its route is described in the Unesco website:

-

“For the first 90 km [from Rome, Via Appia ran straight [across the Pontine marshes] to Tarracina. ... for the last 28 [of these 90 km, it was flanked] by a canal collecting waters of the reclamation works; travellers could then change to boats instead of travelling in wagons or on horseback. After Tarracina, the road swerved towards Fundi, across the towering gorges of Itri and then down to Formiae, Minturnae and Sinuessa; from there straight again towards Casilinum ... on the river Volturnus, and then on to ...Capua ... .”

As Stephen Oakley (2005, at pp. 373-4) suggested that:

-

“From Minturnae, the original course to Capua is uncertain, but it probably passed through Suessa Aurunca and the ager Falernus. Later, it passed through Sinuessa, but this route would have left the new Latin colony at Suessa Aurunca isolated: [this route is unlikely to have been followed before the foundation of the citizen colony of Sinuessa in 296 BC]”

He observed that:

-

“The construction of Via Appia was one of the most important [events] in Roman history: it was the first road that the Romans constructed for imperialistic purposes, and the precedent was to be repeated all over what was to become the Roman Empire.”

Read more:

D. Roller, “A Historical and Topographical Guide to the Geography of Strabo”, (2018) Cambridge

M. Fronda and F. Gauthier , “Italy and Sicily in the Second Punic War: Multipolarity, Minor Powers, and Local Military Entrepreneurialism”, in

T. Ñaco del Hoyo and F. López Sánchez (eds.), “War, Warlords and Interstate Relations in the Ancient Mediterranean”, (2017) Boston

J. Prag, “Cities and Civic Life in Late Hellenistic Roman Sicily”, Cahiers Du Centre Gustave Glotz 25 (2014) 165-208

G. Tols et al., “Minor Centres in the Pontine Plain: the Cases of 'Forum Appii' and 'Ad Medias'’”, Papers of the British School at Rome, 82 (2014) 109-134

J. Pelgrom, “Colonial Landscapes: Demography, Settlement Organisation and Impact of Colonies founded by Rome (4th-2nd centuries BC)”, (2012) thesis, Leiden University

G. Camodeca, “Regio I (Latium et Campania): Campania”, in

M. Silvestrini (Ed.), “Le Tribù Romane: Atti della XVIe Rencontre sur l’Epigraphie du Monde Romaine (Bari, 8-10 Ottobre 2009)”, (2010) Bari, at pp. 179-83

S. Roselaar, “Public Land in the Roman Republic: A Social and Economic History of Ager Publicus in Italy, 396 - 89 BC”, (2010) Oxford

H. Solin, “Problemi delle tribù nel Lazio meridionale”, in

M. Silvestrini (Ed.), “Le Tribù Romane: Atti della XVIe Rencontre sur l’Epigraphie du Monde Romaine (Bari, 8-10 Ottobre 2009)”, (2010) Bari, at pp. 71-9

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume III: Book IX”, (2005) Oxford

T. C. Brennan, “The Praetorship in the Roman Republic”, (2000) Oxford

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume II: Books VII and VIII”, (1998) Oxford

M. Humm, “Appius Claudius Caecus et la Construction de la Via Appia”, Mélanges de l'Ecole Française de Rome (Antiquité), 108:2 (1996) 693-746

J. Linderski, “Legibus Praefecti Mittebantur (Mommsen and Festus 262. 5, 13 L)”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 28:2 (1979) 247-250

A. N. Sherwin-White, “The Roman Citizenship (Second Edition)”, (1973) Oxford

L. Ross Taylor, “The Voting Districts of the Roman Republic: The 35 Urban and Rural Tribes”, (1960) Rome

T. Cornell, “Crisis and Deformation in the Roman Republic: the Example of the Dictatorship”, in

V. Gouschin and P. Rhodes (Eds), “Deformations and Crises of Ancient Civil Communities” (2015) Stuttgart, at pp. 101-26

P. Camerieri, “Il Castrum e la Pertica di Fulginia in Destra Tinia”, in:

G. Galli (Ed.), “Foligno, Città Romana: Ricerche Storico, Urbanistico e Topografiche sull' Antica Città di Fulginia”, (2015) Foligno, at pp. 75-108

J. C. Yardley (translation) and D. Hoyos (introduction and notes), “Livy: Rome's Italian Wars: Books 6-10”, (2013), Oxford World's Classics

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume IV: Book X”, (2007) Oxford

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV Secolo a.C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume III: Book IX”, 2005 (Oxford)

S. Sisani, “Lucius Falius Tinia: Primo Quattuorviro del Municipio di Hispellum”, Athenaeum, 90.2 (2002) 483-505

A. Drummond, “The Dictator Years”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 27:4 (1978), 550-72

W. Harris, “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

E. Salmon, “Samnium and the Samnites’, (1967) Cambridge

W. B. Anderson, “Contributions to the Study of the Ninth Book of Livy”, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 39 (1908) 89-103

Return to Site Map: Romans