Gallic War (283 BC)

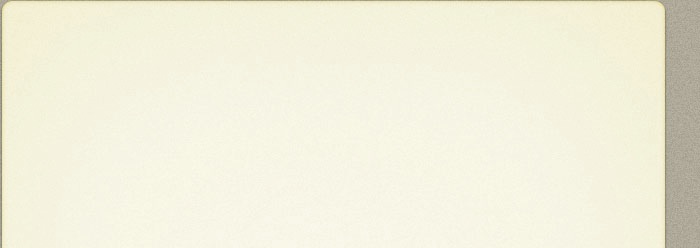

Colonies underlined in blue: Narnia (299 BC); Hadria, Castrum Novum and Sena Galica (280s BC - see below);

Ariminum (268 BC); Firmum Picinum (264 BC); Spoletium (241 BC)

Roman allies underlined in turquoise: Camerinum (310 BC); Ocriculum (308 BC); and the Picenti (299 BC)

Defeated peoples underlined in black: Umbrians (308 BC);

some Etruscans, including Arretium, Perusia and Volsinii (294 BC); Sabines and Praetuttii (290 BC)

Blue road (‘proto-Flaminia’ = most convenient route from Rome to the Adriatic coast in 295 - 220 BC

(see, for example, Federico Uncini , referenced below, at pp. 21-9)

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

Death of the Praetor L. Caecilius and Roman Envoys (283 BC)

Polybius recorded that, in 283 BC:

-

“... the Gauls besieged Arretium, [an Etruscan town that had agreed a truce for 40 years with the Romans in 294 BC]. The Romans went to the assistance of the town and were beaten in an engagement under its walls. Since the strategos (praetor) Lucius had fallen in this battle, Manius Curius [Dentatus] was appointed in his place. He sent ambassadors to treat with the Gauls for the release of prisoners, but the Gauls treacherously murdered them”, (‘Histories’ 2: 19: 7-10).

The summary of Livy’s now -lost Book 12 recorded these events in a different order:

-

“When Roman envoys were killed by Gallic Senones, war was declared against the Gauls. The praetor L. Caecilius and his legions were killed by them” (‘Periochae’, 12:1 ).

Probably drawing on Livy’s now-lost account, Paulus Orosius recorded that:

-

“... during the consulship of Dolabella and Domitius [283 BC], the Lucanians, Bruttians, and Samnites made an alliance with the Etruscans and Senonian Gauls, who were attempting to renew war against the Romans. The Romans sent ambassadors to dissuade the Gauls from joining this alliance, but the Gauls killed them. The praetor Caecilius was sent with an army to avenge their murder and to crush the uprising of the enemy. However, he was overwhelmed by the Etruscans and Gauls, and perished. Seven military tribunes were also slain in that battle, many nobles were killed, and 30,000 soldiers likewise met their death”, (‘History against the Pagans’, 3: 22).

Reconciliation of the Polybian and the Livian Traditions

Corey Brennan (referenced below, 1994, at p. 429) observed that:

-

“Both traditions must refer to the death of the same Roman commander (presumably L. Caecilius Metellus Denter, the consul of 284 BC, the only L. Caecilius known to be active at that time) and to the same occasion.”

In other words, the praetor that Polybius identified only as ‘Lucius’ must have been L. Caecilius Metellus Denter, the consul of 284 BC. Since the fasti Capitolini do not mention his death while consul, the war in which he was killed (as praetor) must have taken place in 283 BC.

Corey Brennan (referenced below, 1994, at p. 438) observed that:

-

“The Livian epitomes hint at an even more dramatic story [than that of Polybius]: although the massacre of the envoys is a causus belli (as in Polybius), the death of the praetor L. Caecilius Metellus Denter follows. This version is a bit illogical: it may be asked why the praetor was at Arretium if the Senones killed the Roman legati in their native land, as all the sources seem to agree.”

Brennan suggested (at p. 438) that:

-

“The following is probably the most we can make out of our conflicting sources:

-

✴Near the end of consular year 284 BC, certain Gauls ... besieged the pro-Roman town of Arretium.

-

✴The Romans sent the consul Caecilius to relieve it.

-

✴[Since Caecilius was] unable to achieve this ... [before the end of the consular year], he was elected praetor ... for the following year.

-

✴In early 283 BC, Caecilius, while still in charge of what had been his consular army, ... [returned to] Arretium ..., [where] the Gauls ... were now joined by rebel Etruscans.

-

✴Caecilius met his death at the hands of their combined forces.

-

✴As it was still quite early in the year, the Romans elected a praetor suffectus, the experienced consul M’ Curius Dentatus, to replace Caecilius.”

It would have been at this point that Curius sent envoys into the territory of the Senones to negotiate the release of prisoners of war, a decision that led to their murder.

Appian and Polybius

Appian gave two essentially identical accounts of an occasion on which the Senones murdered Roman envoys in 283 BC:

-

✴“The Senones, although they had a treaty with the Romans, nevertheless furnished mercenaries against them. The Senate therefore sent an embassy to them to remonstrate against this infraction of the treaty. Britomaris, the Gaul, being incensed against the Romans on account of his father (who had been killed by the Romans while fighting on the side of the Etruscans in this very war), murdered the ambassadors while they held the [herald's staff] and wore the garments that symbolised their office. He then cut their bodies in small pieces and scattered them in the fields. ”, (‘Gallic Wars’, 2.13).

-

✴“Once, a great number of the Senones, a Gallic tribe, aided the Etruscans in war against the Romans. The latter sent ambassadors to the towns of the Senones and complained that, while they were under treaty stipulations, they were furnishing mercenaries to fight against the Romans. Although they bore the [herald's staff] and wore the garments of their office, Britomaris cut them in pieces and flung the parts away, alleging that his own father had been slain by the Romans while he was waging war in Etruria”, (‘Samnite Wars’, 2.13).

Corey Brennan (referenced below, 1994, at p. 426) observed that, despite some differences, these two accounts probably relate to the events described by Polybius (above), and that they:

-

“... contribute some details ... that are not found in other authors:

-

✴the slaughter of the [envoys by the Senones] is put in the context of an Etruscan war;

-

✴the Romans sent these [envoys] to the towns of the Senones ... because, [although they had a treaty with the Romans], they had furnished mercenaries to the Etruscans ... ; and

-

✴the Gaul Britomaris ... , who had lost his father in this war, killed the legates with his own hands.”

Brennan reconciled the accounts of Polybius and Appian by suggesting (at p. 438) that, soon after the election of the new consuls of 283 BC, the Romans:

-

“... prepared to advance into Etruria. In connection with this campaign, [the praetor suffectus] M’ Curius Dentatus sent [envoys] to the Senones [Polybius] in an effort to:

-

✴regain Roman prisoners-of-war (Polybius); and

-

✴dissuade them from assisting the Etruscans as mercenaries (Appian).”

Conquest of the Senones (283 BC)

One thing that is clear from the sources above is that the death of L. Caecilius and of the Roman envoys provided the causus belli for a Roman attack on the Senones. Thus, according to Polybius, when they heard of the murder of the envoys:

-

“... the infuriated Romans sent an expedition against [the Gauls] that was met by the [Gallic] tribe called the Senones. This [enemy] army was cut to pieces in a pitched battle, [following which], the rest of the tribe was expelled from [their territory on the Adriatic coast]. The Romans sent the first colony that they ever planted in Gaul [to this territory]: this colony was named Sena [Gallica] for the tribe that had formerly occupied it”, (‘Histories’ 2: 19: 10-12).

Polybius did not identify the Roman commander who defeated the Senones and confiscated their territory. However, Appian (again in two essentially identical accounts) identified him as P. Cornelius Dolabella, one of the new consuls of 283 BC:

-

✴The consul [Dolabella], who learned of this abominable deed while he was on the march, moved with great speed against the towns of the Senones by way of the Sabine country and Picenum, and ravaged them all with fire and sword. He reduced the women and children to slavery, killed all the adult males without exception, devastated the country in every possible way, and made it uninhabitable for anybody else. He then carried off Britomaris alone as a prisoner for torture”, (‘Gallic Wars’, 2.13).

-

✴The consul [Dolabella], who learned of this abominable deed while he was on the march, abandoned his campaign against the Etruscans and dashed with great rapidity by way of the Sabine country and Picenum against the towns of the Senones, which he devastated with fire and sword. He carried their women and children into slavery, and killed all the adult youth except a son of Britomaris, whom he reserved for awful torture, and led in his triumph”, (‘Samnite Wars’, 2.13).

This is confirmed by:

-

✴Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who referred to:

-

“... P. Cornelius [Dolabella], who, while consul [in 283 BC], had waged war on the whole tribe of Gauls and had slain all their adult males, ...”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 19: 13: 1); and

-

✴Florus recorded that:

-

“... near the lacus Vadimonis [see below] in Etruria, [P. Cornelius] Dolabella destroyed all that remained of the tribe [of the Senones], so that none might survive of the race to boast that he had burnt the city of Rome”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 1: 8: 21).

All of the surviving sources that identify the commander who destroyed the Senones identify him as P. Cornelius Dolabella, the consul of 283 BC. Corey Brennan (referenced below, at p. 425) pointed out that, although Polybius recorded that M’ Curius Dentatus sent envoys to the Senones in that year, he:

-

“... does not state that it was M.' Curius Dentatus who marched against the Senonian Gauls or planted the colony [of Sena Gallica], an erroneous supposition which has caused much confusion.”

This apparent confusion has persisted in part because the relevant entries in the Augustan fasti Truiumphales are now lost. John Rich observed that:

-

“The Capitoline entry for Curius’ final triumph in 275 BC over Pyrrhus and the Samnites confirms that it was his fourth. The entries for his first three are all lost in the lacuna between the triumphs of 291 and 282 BC, a period for which the loss of Livy also leaves us poorly informed. Curius’ first two triumphs, over the Samnites and Sabinesm are attested as held in his consulship in 290 BC, making him the first to triumph twice in the same magistracy. For his third we have only the report in his short biography in the late and often erratic ‘De viris illustribus’, 33: 3] that:

-

“The third time he entered the city in ovation from the Lucani.”

-

... Earlier writers supposed that he held this ovation, like his triumphs, as consul in 290 BC or alternatively as proconsul in 289 (so Degrassi). However, Brennan, [as above], has made a strong case for dating the ovation to 283, when the Romans are attested as coming into conflict with the Lucanians, and for supposing that Curius defeated them and held his ovation as praetor, having been appointed to the office as a suffect following the death of L. Caecilius Metellus Denter in battle with the Gauls, as reported by Polybius (2.19.8). Since this appears to be the best reconstruction available, I have adopted it in my [reconstructed triumphal list].”

Thus, in this reconstruction of the fasti Triumphales (see his Table 6, at p. 248), Rich proposed the following consecutive entries (100-3):

-

✴290 BC: M’ Curius Dentatus I, consul de Sabnitibus

-

✴290 BC: M’ Curius Dentatus II, consul, de Sabineis

-

✴283 BC: M’ Curius Dentatus III, praetor ? (Ovation) de Lucaneis

-

✴283 BC: P. Cornelius Dolabella, consul, de Gallis Senonibus

Colony at Sena Gallica

There are two distinct traditions for the date of the foundation of the colony at Sena Gallica:

-

✴An entry on the surviving summary of Livy’s now-lost Book 11 records that:

-

“Colonies were founded at Castrum [Novum in Picenum], Sena [Gallica] and Hadria”, (‘Periochae’, 11: 7).

-

It seems that this book began in 290 BC and ended before the death of the praetor L. Caecilius in 283 BC (which, as we have seen, was the first event recorded in Book 12). If the entries in the perioche are in date order, then these three colonies would have been founded:

-

•after the double triumph of M’ Curius Dentaus recorded at 11: 5, which (as we have seen) he celebrated as consul of 290 BC; and

-

•before the census recorded at 11: 9, which Robert Broughton (referenced below, at p. 184 and note 2) dated to 289 BC.

-

✴However, as we have seen:

-

•according to Polybius, the colony was founded in 283 BC, on land that the Romans had confiscated from the Senones; and

-

•although Appian did not mention the foundation of the colony, he did record that, in revenge for the murder of the legates, Dolabella, who was consul in 283 BC, had:

-

“... ravaged [all of the towns of the Senones] with fire and sword. He reduced the women and children to slavery, killed all of the adult males without exception, devastated the country in every possible way, and made it uninhabitable for anybody else”, (‘Gallic Wars’, 2.13).

In fact, these records can probably be reconciled: as Michael Fronda (referenced below, at p. 429) pointed out,:

-

“In his surviving books, Livy reports colonial foundations in one of two ways: he either:

-

•states that a colony was founded, using formulae as colonia(e) deducta(e) or deduxerunt coloniam/-as: or

-

•mentions that legislation was passed to found a colony at some later point, employing future constructions such as ut colonia(e) deducere tur/ -ntur or colonia(e) deducenda(e).

-

[However], no matter what phrase Livy uses, the periochae ... invariably report colonial foundations with the formula colonia(e) deducta(e).

In other words, in this case, we can assume that the legislation for the foundation of all three colonies was passed in 290-89 BC, but we cannot automatically assume that all three were then immediately founded ‘on the ground’. It is, of course, extremely unlikely that the Romans would have passed enabling legislation for the foundation of colonies on land that was not under Roman control:

-

✴This is not a problem in relation to the colonies of Castrum Novum in Picenum and at Hadria: since, according to Florus, M’ Curius Dentatus had confiscated the necessary land for during his conquest of the Sabines in 290 BC, when:

-

“... the Romans laid waste with fire and sword all the tract of country that is enclosed by the Nar [on which stood the colony of Narnia], the Anio and the sources of the Velinus, and bounded by the Adriatic Sea. By this conquest, so large a population and so vast a territory was reduced, that even [Curius] could not tell which was of greater importance”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 1: 10).

-

✴On the other hand, it is a problem for Sena Gallica unless there are grounds for believing that the land on which it was subsequently founded was in Roman hands in ca. 290 BC.

An odd aspect of Appian’s account of the events of 283 BC (above) might throw some light on this potential problem: he recorded that, in 283 BC, the Roman legates who were sent to the Senones had argued that the fact that Senonian mercenaries were taking service with Rome’s enemies was represented a violation of a Romano-Senonian treaty. This information is not found in any of our other surviving sources, but Nathan Rosenstein (referenced below, at pp. 38) argued that the Romans had probably forced this treaty on the Senones after their victory over the Samnites, Gauls, Etruscans and Umbrians at Sentinium (on the border of Senonian territory) in 295 BC, and that they might also have forced them to cede a portion of their land to Rome at this time. If so, then it is at least possible that the Romans passed legislation enabling the foundation of a colony here in 290-89 BC, but that the actual foundation of the colony was postponed until the land in question was more securely under Roman control, which would account for the fact that the actual foundation probably took place after the conquest of 283 BC.

It seems that Sena Gallica was formally a maritime citizen colony, as evidenced by the fact that (according to Livy, ‘History of Rome’, 27: 38: 4) it was among seven such colonies that pleaded their ‘sacrosancta vacatio militiae’ [notionally inviolable exemption from military service] in 207 BC. It is often asserted that only 300 citizen settlers were enrolled for this type of colony, and that this was therefore the case at Sena Gallica. However, the number of colonists is known for only 6 of about 20 known maritime colonies:

-

✴Tarracina, which also appears in Livy’s list such colonies in 207 BC; and

-

✴5 founded in 194 BC (Livy, ‘History of Rome’, 32: 29: 3).

It is true that the number of colonists in each of these 6 was indeed 300. However this does not prove that this necessarily applied at Sena Gallica (or at any other 13 known colonies of this type). Indeed, according to Giuseppe Lepore (referenced below, in the English abstract of this paper), the archeological evidence suggests that this:

-

“... first [maritime colony] on the Adriatic [had] the shape and size of a [Latin colony], recalling the situation that, 20 years later, characterised the [Latin] colony of Ariminum [on the northern border of the ager Gallicus]. The new [evidence gained from the excavations] allows us to hypothesis that Rome adopted a new form of [citizen colony as part of] its ‘Adriatic policy’.”

In the body of his paper (at pp. 231-2), he expanded as follows:

-

“We can recognise [from the new archeological data] a city of dimensions quite unlike those of other maritime colonies: we are looking at [an area of some] 18 hectares, compared with 2-2.5 hectares for the older maritime colonies on the Tyrhenian coast” (my translation).

He suggested that this new model had also applied at the citizen maritime colony of Castrum Novum Picenum, which, as we have seen, had been founded to the south (on land recently confiscated from the Praetutti) at about the same time. More recently, Frank Vermeulem (referenced below, at p. 193 pointed out that the Adriatic coastal plain had been essentially unurbanised at the start of the 3rd century BC, and argued (at p. 194) that the series of colonies that the Romans built here shortly thereafter can be:

-

“... seen as successful weapons used by Rome to take full possession of central Italy.”

He noted (at p. 195) that our surviving sources record five such colonies in the two decades following the conquest of the ager Gallicus:

-

✴the citizen colonies of Castrum Novum (ca. 290 BC) and Sena Galica (2803 BC;

-

✴the Latin colonies of Hadria (ca. 290 BC), Ariminum (268 BC); Firmum Picinum (264 BC);

and observed that, on the basis of archeological evidence:

-

“... despite their different legal status, they [apparently had] characteristics that [were] very similar to those of quite large population centres, [and would have] generated a strategically well-balanced urban strip along the coast, controlling the sea and the now expanded easternmost part of the ager Romanus.”

Federico Uncini (referenced below, at pp. 21-9) suggested that, before the building of Via Flaminia in 220 BC, the Romans could have reached it using existing roads (including those that he designated as the proto-Flaminia illustrated on the map at the top of the page). Nevertheless, the lines of communication were long and, as Graham Mason (referenced below, at p. 82) observed, since it would not have been easily provisioned from Rome, the colonists would have needed to provide for themselves by farming the broad alluvial plain on which it was located.

Roman Victory at the Lacus Vadimonis (283BC)

According to Polybius, still in 283 BC:

-

“Seeing the expulsion of the [Gallic] Senones [from their territory on the Adriatic coast], and fearing the same fate for themselves, the [neighbouring Gallic tribe known as the] Boii [whose territory was in the Po valley]: made a general levy; summoned the Etruscans to join them; and set out to war [against Rome] . They mustered their [combined] forces near the lacus Vadimonis and there gave the Romans battle”, (‘Histories’, 2:20).

As noted on my page on an earlier engagement here between the Romans and the Etruscans (in 310/9 BC), although this ancient lake no longer exists, its general location is known: it was in Etruscan territory (on the left bank of the Tiber), about:

-

✴50 km southeast of the Etruscan city-state of Volsinii; and

-

✴70 km east of the Etruscan city-state of Tarquinii.

More importantly for the Romans, it was about 40 km north of the Latin colonies of Sutrium and Nepet, which guarded the way to Rome.

Polybius gave no description of the battle at the lacus Vadimonis, simply noting that:

-

“... the Etruscans suffered a loss of more than half their men, while scarcely any of the Boii escaped”, (‘Histories’, 2:20).

However, it seems that the Romans’ victory here was not completely decisive: according to Polybius, in the following year (282 BC), the Boii and the Etruscans:

-

“... joined forces once more: after mobilising even those of them who had only just reached manhood, they gave the Romans battle again. It was not until they had been utterly defeated in this engagement that they humbled themselves so far as to send ambassadors to Rome and to make a treaty”, (‘Histories’, 2:20).

Corey Brennan (referenced below, 1994, at p. 427) observed that:

-

“Although Polybius does not name the Roman commander [at the lacus Vadimonis], later tradition unanimously ascribes the victory to Dolabella.”

He cited (inter alia):

-

✴Florus

-

“... near the Lake of Vadimo in Etruria, Dolabella destroyed all that remained of the [Gallic Senones], so that none might survive of the race to boast that [his ancestors] had burnt the city of Rome”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 1: 8: 21); and

-

✴Eutropius

-

“After an interval of a few years [after the end of the Third Samnite War in 290 BC], the forces of the Gauls united with those of the Etruscans and the Samnites against the Romans; but, as they were marching to Rome, they were cut off by the consul Cnaeus [sic] Cornelius Dolabella”, (‘Abridgement of Roman History’, 2.10).

He concluded that, when the Romans became aware that the Etruscans and the Boii were mustering a their men at the lacus Vadimonis:

-

“Dolabella must have hurried back from [devastating] the land of the Senones to return to his original mission, a campaign against the Etruscans.”

Polybius also failed to identify the Roman commander who defeated the remnants of the enemy armies after the battle at the lacus Vadimonis. However, Appian seems to have identified him as Dolabella’s consular colleague, Cnaeus Domitius Calvinus:

-

“A little later [i.e. immediately after Dolabella had ravaged and confiscated their territory], those Senones who were serving as mercenaries, having no longer any homes to return to, fell boldly upon the consul Domitius. After he defeated them, they killed themselves in despair. Such punishment was meted out to the Senones for their crime against the ambassadors.”, (‘Gallic Wars’, 2.13).

Corey Brennan (referenced below, 1994, at p. 427) observed that this victory:

-

“... is found only in Appian. It is not immediately clear what Appian is talking about. Some scholars have (wrongly) thought Appian is referring to Vadimon. ... I would suggest that Domitius' conflict with the Senonian Gauls [actually] belongs to the period immediately following Vadimon, but still in his consular year of 283 BC.”

He suggested (at p. 428) that the following surviving fragment from Cassius Dio might support this hypothesis:

-

“... When the enemy saw that another general had also arrived, they ceased to heed the common interests of their expedition: each cast about to secure his own safety, as is the common practice of those who:

-

✴form a union that is not cemented by kindred blood; or

-

✴make a campaign without common grievances; or

-

✴lack a single commander:

-

... And so, arranging their flight, each in the way that seemed safest in his own judgment ... ”, (‘Roman History’, 8: fragment 38)

As Brennan observed (at p. 428):

-

“It has long been thought that [the now-unidentified anti-Roman alliance was that of the] Etruscans, Boii and Senones, at the time of Vadimon: this must be correct. I would further suggest that that the [the now-unidentified approaching second Roman commander] is the consul Domitius, who had now moved into Etruria ... to support his colleague ... Dolabella. It is not impossible that, after defeat at Vadimon and the splintering of the coalition (described here by Dio), a band of desperate Senones attacked Domitius, with dire results ”

Revolt of Volsinii (282-280 BC)

According to the Periochae, wars against the Volsinians and Lucanians broke out in 282 BC, when the Romans

-

“... decided to support the inhabitants of Thurii against them” (‘Periochae’, 11).

This incident formed part of the growing tension between the Romans and the inhabitants of Tarentum, the important Greek city in southern Italy that regarded its neighbour Thurii (also Greek) as within its sphere of influence. Thus, when Thurii turned to Rome rather than to Tarentum for protection from the Lucanians, hostilities became inevitable.

Etruscan Revolt (ca. 280 BC)

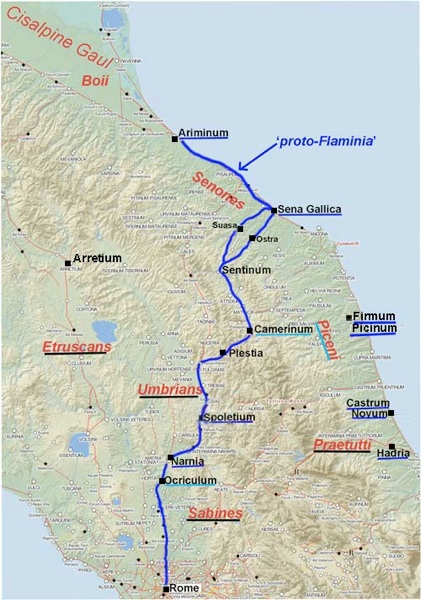

Latin colonies: Nepete and Sutrium (383 BC); Cosa (273 BC); Heba ? (ca. 150 BC)

Maritime citizen colonies (ca. 264 - 245 BC): Castrum Novum; Pyrgi; Alsium; Fregenae

Citizen colony: Saturnia (183 BC); Graviscae (181 BC)

Prefectures listed by Festus: Caere ; Saturnia

Other prefectures: Forum Clodii (CIL XI 3310a, Pliny the Elder); Statonia (Vitruvius)

Underline indicates known or likely tribal assignation:

Tribes formed in 387 BC: Turquoise = Tromentina (Veii); Blue = Stellatina;

Red = Sabatina; Yellow = Arnensis (Blera and Ocriculum)

Green = Voltinia (old tribe)

Statonia has recently been located near Bomarzo, as shown on the map

The location that was previously assigned to it (between Vulci and Saturnia) is indicated in italics

It seems that hostilities resumed in Etruria in ca. 280 BC: for example, the ‘Fasti Triumphales’ record triumphs awarded to:

-

✴Quintus Marcius Philippus, over the Etruscans in 281 BC; and

-

✴Titus Coruncanius, over the Vulsinienses and Vulcientes (i.e. over Volsinii and Vulci) in 280 BC.

Land Confiscated from Caere in ca. 280 BC

Cassius Dio recorded that:

-

“The [people of Caere], when they learned that the Romans were disposed to make war on them, despatched envoys to Rome before any vote was taken and obtained peace upon surrendering half of their territory” (‘Roman History’, 10: fragment 33).

Scholars are divided on the likely date of these events at Caere. For example:

-

✴William Harris (referenced below, p. 83 and note 3) dated them to 274 or 273 BC, after the end of the Pyrrhic War; while

-

✴Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, 2010, at p. 42) asserted that:

-

“...the [Romans’] last war with Etruria ended in 281 BC. It is usually assumed that, on this occasion, Caere, Vulci, Volsinii and Tarquinii lost part of their land.”

The tribe of Caere is usually deduced from a funerary inscription (known in two versions, CIL XI 3615 and 3257 that can be dated to the period 40-70 AD), which commemorates Titus Egnatius Rufus: the inscriptions were documented at Sutri in the 16th century, but Egnatius’ cursus included the post of dictator, an office that he almost certainly held at Caere. Early readings of the inscription had Egnatius assigned to the Voturia tribe (see, for example, Lily Ross Taylor, referenced below, at p. 276). However, there are two other inscriptions from Caere that suggest that this should be read as the Voltinia (one of the original 17 rural tribes):

-

✴an inscription (CIL XI 7613) from the Necropoli della Banditaccia commemorates Lucius Campatius of the Voltinia; and

-

✴an inscription (AE 2003, 0648) from Caere that commemorates a now-anonymous ‘L(ucius)’, who was assigned to the Voltinia.

Thus, we can reasonably assume that Egnatius was also assigned to the Voltinia, and that this was the tribal assignation of Caere from the time of its enfranchisement (which, as discussed below, possibly occurred after the Social War).

As indicated on the map above, the Voltinia tribe, as were three nearby centres:

-

✴at Forum Clodii; and

-

✴at two of the colonae maritimae on this stretch of coast: Castrum Novum and Alsium.

Forum Clodii

The tribe of Forum Clodii can be deduced from two inscriptions commemorating Quintus Cascellius Labeo:

-

✴an inscription (CIL XI 3303) from Forum Clodii, which is dated to 18 AD, reproduces a decree of the decurions in which it is noted that Cascellius had undertaken to finance in perpetuity a banquet on the birthday of the Emperor Tiberius; and

-

✴his epitaph (CIL VI 3510) from Rome gives his tribe as the Voltinia.

Other inscriptions from Forum Clodii that confirm this tribal assignation include: CIL XI 7556; AE 1992, 597; and AE 1992 598. As discussed below, Forum Clodii was almost certainly established on the Via Clodia for newly-settled Roman citizens,: they were presumably assigned to the Voltinia at the unknown date of settlement.

Coloniae Maritimae of 264-41 BC

There is epigraphic evidence that suggests that two of the citizen coloniae maritimae founded during the First Punic War (264-41 BC) were also assigned to the Voltinia:

-

✴An inscription (CIL VI 0951, dated to 97 AD) from Rome records Lucius Sertorius Evanthus, of the Voltinia, an aedile of a colony ‘C(---) N(---)’: this is usually completed as Castrum Novum and considered to be the Etruscan colonia maritima of this name.

-

✴Annarosa Gallo (referenced below, at p. 351 and note 36) referred to a recently-discovered fragmentary inscription from Alsium that records a now-anonymous member of the Voltinia.

The tribal assignations of the other two of these coloniae maritimae (Pyrgi and Fregenae) are unknown. However, most scholars (see, for example, Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, 2010, at pp. 315-6, entry 26) assume that all four were founded on land that had been confiscated from Caere.

Viritane Settlement on Land Confiscated from Caere: Discussion

Having analysed the evidence for the Voltinia in the area around Caere, Annarosa Gallo (referenced below, at pp. 351-2) put forward the hypothesis that:

-

“... the censors had progressively extended the tribe of the Roman citizens who were already settled on the ager publicus that had been confiscated [from Caere in 273 BC]” (my translation).

She also suggested that this extension of the Voltinia had encompassed not only the three centres above for which there is epigraphic evidence, but also Pyrgi and Fregenae (see her map at p. 343). On this model:

-

✴the putative viritane settlers on the land confiscated from Caere in ca. 280 BC were assigned to the Voltinia;

-

✴this assignation was given to the citizen colonists enrolled in the coloniae maritimae in 264-41 BC and to the citizen settlers at Forum Clodii (which, I suggest below, was constituted in the 2nd century BC); and

-

✴Caere itself was assigned to the Voltinia when it was enfranchised, which might not have occurred until after the Social War.

However, I doubt that there would have been much viritane settlement here during the Pyrrhic War (280-75 BC) and the First Punic War (264-41 BC): the Latin colony at Cosa had been founded to counter the growing naval threat from Carthage and this threat became manifest in the war that followed.

An alternative model might be suggested by looking at viritane settlement in three adjacent territories that were conquered in 290 BC but probably settled in ca. 270 BC: Sabina tiberina, the alta Sabina, and the territory of the Praetutti, on the Adriatic in southern Picenum. The developments here are discussed in by page on the ‘Settlement of the Sabine Lands’: in summary:

-

✴The main centres of Sabina tiberina, including Cures, were assigned to the Sergia, one of the original 17 rural tribes, presumably when they were given full Roman citizenship in 268 BC.

-

✴The other areas were assigned to one of two tribes that were formed only in 241 BC:

-

•The main centres of the alta Sabina (including Reate) were assigned to the Quirina.

-

•The Roman ‘new town’ of Interamnia Praetuttorum in the territory of the Praetuttii was assigned to the Velina.

Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 64) observed that these names “did not fit” the areas to

which they were assigned:

-

✴the Quirina, which (according to Festus) was named for Cures in Sabina tiberina, was assigned to Reate and the other centres of the alta Sabina; while

-

✴the Velina, which was named for the lacus Velinus , near Reate, was assigned to Picenum on the Adriatic, starting at Interamnia Praetuttorum.

She suggested (at pp. 64-5) that the names for the new tribes had been chosen by Curius Dentatus (who had conquered the territory and subsequently drained the lacus Velinus in order to facilitate its settlement) when he became censor in 272 BC. This putative plan would have been disrupted when Curius was forced to resign the censorship on the death of his colleague in mid-term. Curius himself died in 270 BC. Lily Ross Taylor (as above) suggested that:

-

“... the next censors, in 269-8 BC, made a different arrangement for Cures, placing it in the [existing tribe of the] Sergia. The [Quirina and the Velina existed only ‘on paper’] until the First Punic War was over.”

In other words, although the Quirina and the Velina had existed on paper since 272 BC, they had remained unassigned, first because of the death of Curius Dentatus and then because of the distraction of the First Punic War. On this model, the significant number of citizen settlers in the alta Sabina and the erstwhile territory of the Praetutti would have remained in their original tribes until 241 BC.

If we return now to the ager publicus near Caere, I argued above that:

-

✴the first significant influx of citizen settlement here probably comprised the 1,200 or so colonists that were enrolled at the four the coloniae maritimae during the First Punic War; and

-

✴the purpose of these colonies might well have included the facilitation/ nucleation of citizen settlement on the surrounding ager publicus after the war.

On the precedent of the Sabine lands, we might reasonably assume that they retained their original tribal allocations until 241 BC, when those at Castrum Novum (and possibly those at Pyrgi and Fregenae) were assigned to the Voltinia. If this is correct, then we might make minor changes to the model proposed by Annarosa Gallo (above):

-

✴the citizen colonists enrolled in the coloniae maritimae during the First Punic War retained their original tribes until the war was over, at which point they were assigned to the Voltinia;

-

✴the putative viritane settlers on the ager publicus near Caere and the citizen settlers at Forum Clodii were so-assigned thereafter; and

-

✴when Caere itself was enfranchised (which might not have occurred until after the Social War) it to was assigned to the Voltinia.

We know that both Caere and Forum Clodii were constituted as prefectures at some point: I argue below that the Roman prefects who had their seats here administered the legal affairs of this body of citizen settlers.

Land Confiscated from Tarquinii in ca. 280 BC

According to Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 275), 8 of the 13 towns assigned to the Stellatina tribe (one of the four rural tribes organised in 387 BC after the fall of Veii) were in the Augustan seventh region:

-

✴Capena, possibly in 389 BC, when those Capenatians who had remained loyal to Rome during the Gallic sack of Rome were given full citizenship and received an allotment of land;

-

✴Graviscae, the citizen colony founded in 181 BC; and

-

✴six centres that were enfranchised after the Social War:

-

•Tarquinii;

-

•Tuscana;

-

•Ferntium;

-

•Horta;

-

•Nepet; and

-

•Cortona (which is not discussed here because it is some 150 km north of Tarquinii).

In addition, Statonia has recently been tentatively assigned to the Stellatina.

However, it seems likely that there was also a programme of viritane settlement of the coastal plain. It might be possible to develop this hypothesis by considering the subsequent tribal allocations of the area. Unfortunately, the tribe of the colony of Cosa is unknown. However:

-

✴Vulci and Tarquinii, which had both probably suffered land confiscation in ca, 280 BC, were later assigned to tribes that had been formed after the fall of Veii in 387 BC:

-

•Vulci was assigned to the Sabatina, as were: the prefecture/ colony of Saturnia (see below); and the colony of Heba (founded in ca. 150 BC); and

-

•Tarquinii was assigned to the Stellatina, as were: the colony of Graviscae, founded in 181 BC; and (probably, see below) the prefecture of Statonia.

-

✴Caere, together with: the prefecture of Forum Clodii and the maritime colonies of Castrum Novum, Pyrgi, Alsium, and Fregenae, was probably assigned to the Voltinia.

These tribal assignations, which are indicated in the map above, are sourced as follows:

-

✴Those centres assigned to the Sabatina and Stellatina (with the exception of that of Statonia) are taken William Harris (referenced below, at pp. 330-5).

-

✴The evidence for the likely assignation of Statonia to the Stellatina is discussed below.

-

✴So too are all the assignations to the Voltinia.

Land Confiscated from Vulci in 279 BC

According to Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 274) 4 of the 5 towns assigned to the Sabatina tribe (one of the four rural tribes organised in 387 BC after the fall of Veii) were in the Augustan seventh region:

-

✴the citizen colony Saturnia, founded in 183 BC; and

-

✴three centres that were enfranchised after the Social War:

-

•Vulci;

-

•Visentium (discussed below); and

-

•Volaterrae (which is not discussed here because it is some 180 km north of Vulci).

The only centre in her list that was in another regions was Mantua. William Harris (referenced below, at p. 332) suggested that Heba (also in the seventh region) might also have beem assigned to the Sabatina, since a now-lost funerary inscription (AE 1957, o219) from Heba, which dates to the period 200-330 AD commemorated:

C(aio) Petisio C(ai) f(ilio) Sab ...

The EDR database (see the AE link above) accepts the completion ‘Sabatina’, although (like Harris) it notes that Sab ... could alternative;y have been a cognomen. It seems to me that, given the concentration of the Sabatina in the seventh region, we can reasonably assume that this was, indeed the tribe at Heba.

Visentium

According to Debora Rossi (referenced below, at pp. 289-90):

-

“It used to be believed that the territory of Visentium, like most of the area to the west of Lake Bolsena, was on land expropriated from Vulci and reorganised in the first half of the 3rd century BC in a prefecture headed by Statonia. ... However, the recent proposal for the location of Statonia in the Tiber area gives rise to a different geopolitical scenario: [it now seems likely] that the Romans have left under the control of Vulci not only part of the territories between the [rivers] Arrone and Fiora, but also those towards on the western shore of of Lake Bolsena. That being the case, Visentium ... remained dependent on Vulci until it became a municipality: like other communities in the ancient territory of Vulci, it was assigned to the Sabatina tribe. It became a municipium {administered by duoviri, in the middle of the 1st century BC]” (my translation).

Prefecture of Caere (3rd century BC ?)

The Etruscan city of Caere appeared in Festus’ list of prefectures and also in his list of municipia (in a category that also included Aricia and Anagnia).

Mario Torelli (referenced below, at p. 265) incorporated the suggestions of both Beloch and Sherwin-White into the traditional account of Caere’s early incorporation and postulated a simultaneous introduction of the prefecture:

-

“In 273 BC, Caere was the last south Etruscan city to be conquered [by Rome] .... Its [putative ancient] status as civitas sine suffragio was confirmed, but in a new, negative way ... The Romans confiscated half of the Caeretan land ... As a municipium, Caere lost its customary magistrates and was governed by a Roman prefect, who was responsible for justice in the city and throughout the former Caeretan territory. [This territory ?] was occupied by Roman viritane colonists and turned into a praefectura ...”

In fact, there the surviving record of the revolt of 273 BC provides no evidence that, after the revolt, Caere:

-

✴was municipalised;

-

✴lost its customary magistrates; and/or

-

✴was constituted as a prefecture.

These assumptions are based only on information from Festus, who recorded only that Caere was constituted as both a municipium and a prefecture at some time prior to the early Augustan period.

Was Caere Incorporated before the Social War ?

According to Fabio Colivicchi (referenced below, at p. 195), recent excavations at Caere have unearthed evidence that:

-

“... its story ... after 273 BC is no less important than [in its former] splendour. The ancient sanctuaries of the Etruscan city ... were quite active and probably underwent significant renovations after the momentous date of 273 BC, possibly along with a large-scale urban renovation. This was a visible statement of prosperity and continuity of the community (albeit in politically renewed form) rather than of disruption. That the population of Caere was still clearly Etruscan in culture is confirmed by the continuity of funerary customs, ... and by the use of Etruscan as the standard language until the Social War, when the concession of full citizen rights, and therefore the requirement to enrol in a voting tribe, prompted the general adoption of Latin.”

Thus, there is apparently no archeological evidence for the Romanisation of Caere before the Social War. It is true that the ‘renewed’ political form of Caere mentioned by Colivicchi probably included the constitution of a prefecture, as indicated by Festus and suggested by other evidence (discussed below). However, as noted above, we cannot assume that it included the constitution of a municipium: as noted above, Festus is our only source for this information, and his source might well have relied on Strabo, whose testimony differs from that of Livy.

The next mention of Caere in the surviving sources relates to the events of in 205 BC, when Scipio Africanus assembled a fleet at his base at Sicily for an assault on Carthage: according to Livy:

-

“Scipio, though he could not obtain leave [from the Senate] to levy troops ... obtained leave to take with him such as volunteered their services; and also ... to receive what was furnished by the socii (allies) for building fresh ships. First, the states of Etruria engaged to assist the consuls to the utmost of their respective abilities. The people of Caere furnished corn and provisions of every description for the crews; the people of Populoni ... Tarquinii... Volaterrae ... Arretium ... Perusia, Clusium, and Rusella [also furnished supplies]”, (‘History of Rome’, 28: 45: 13-8).

Opinions vary as to the precise significance here of the term socii: for example, William Harris (referenced below, at p. 90), who assumed that Caere was a civitas sine suffragio at this time, did not see any problem with its inclusion in Livy’s list of Etruscan socii. However, it seems to me that this passage implies that Caere, like the other Etruscan city-states, still enjoyed nominal independence under Roman hegemony.

Edward Bispham (referenced below, at p. 462) included Caere in his list of centres that were municipalised in the Republican period, and cited Festus (at p. 466, note 22) in this context. However, he reasonably commented that:

-

“The history of the incorporation of Caere is opaque.”

It seems to me that this history was probably equally opaque to Festus’ source, who might have relied on Strabo (or another similar source), overlooking the contrary testimony of Livy. In other words, the surviving documentary evidence does not, in my view, allow us to conclude beyond doubt that Caere was a civitas sine suffragio prior to the Social War.

Prefecture at Caere

Robert Knapp (referenced below, at p. 32, note 68), who assumed that Caere was a civitas sine suffragio before the Social War, observed that:

-

“.... [this]status is not attested for [the following centres in Festus’ list of prefectures]; Venafrum; Allifae; Privernum; Frusino; Reate; and Nursia. As troublesome as this is, it appears reasonable to suppose these towns to be [civitates sine suffragio] on the basis of the attestation of that status for other towns in Festus' list.”

In other words, in his view, since six of the twelve prefectures in Festus’ list of non-Campanian prefectures are recorded as civitates sine suffragio, the other six must have shared this status. However, as Knapp recognised himself, this is ‘troublesome’. Indeed, given the doubts about the status of Caere, only five of Festus’ twelve non-Campanian prefectures are securely recorded as civitates sine suffragio before the Social War. Thus, it is at least possible that some of the other seven of these prefectures, including Caere, were constituted for a period as prefectures but not as municipia.

As noted above, Mario Torelli (referenced below, at p. 265) suggested that Caere was constituted as a prefecture in 273 BC. He found evidence to support this hypothesis in the form of the following graffiti, which was scratched on the wall of an underground complex at Caere:

C(aios) Genucio(s) Clousino(s), prai(? fectos)

He identified the subject as Caius Genucius Clepsina, the consul of 276 and 270 BC, and suggested (given these dates) that Genucius had also been Caere’s first Roman prefect in 273 BC. However, Christer Bruun (referenced below, at p. 275) was more circumspect:

-

“There is an on-going debate about what the official function of this Roman senator was at Caere [since the completion ‘praifectos’ is not completely secure]. He appears to be the C. Genucius Clepsina who was consul in 276 and 270 BC [although this again is not certain].”

Corey Brennan (referenced below, 2000, at p. 654) also had reservations:

-

“It is possible that C. Genusius, if really the consul [of the 270s BC], was sent to [Caere] as praetor in an earlier period of unrest. ... Alternatively, our C. Genusius [could be] a descendant of the consul of the 270s, to be placed later in (most likely) the 3rd century BC. ... In purely statistical terms, it is overwhelmingly probable that Genucius, whatever his exact date and identity, was a praefectus and not a praetor.”

In other words, the Genucius of the graffiti was probably a prefect, presumably at Caere, but he cannot be identified beyond doubt as the consul of 276 and 270 BC: thus the graffiti most probably supports Festus’ view that Caere was a prefecture, but it does not securely indicate that this prefecture was constituted in 273 BC.

There is other circumstantial evidence that suggests that the prefecture was constituted here in the 3rd century BC: according to Graham Mason (referenced below, at pp. 82-3), the four maritime colonies founded on the Etruscan coast (mentioned above and marked on the map above) were established on land that had been ceded by Caere in ca. 273 BC. Velleius Paterculus gave the foundation dates of three of these colonies:

-

“At the outbreak of the First Punic War [in 264 BC], Firmum [in Picenum] and Castrum [Novum] were occupied by colonies, ... Alsium seventeen years later [i.e. in 247 BC], and Fregenae two years later still”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 14: 8).

It is usually assumed that Pyrgi, like Castrum Novum, was founded in ca. 264 BC. We might reasonably assume that viritane citizen settlement also took place in this period on land that had been confiscated from Caere, and that this might have given rise to the constitution of a prefecture.

We might usefully explore this possibility by exploring the known tribal assignations in this area. The tribe of Caere is usually deduced from a funerary inscription (known in two versions, CIL XI 3615 and 3257), which can be dated to the period 40-70 AD and which commemorates Titus Egnatius Rufus: the inscriptions were documented at Sutri in the 16th century, but Egnatius’ cursus included the post of dictator, an office that he almost certainly held at Caere. Early readings of the inscription had Egnatius assigned to the Voturia tribe. However, there are two other inscriptions from Caere that suggest that this should be read as the Voltinia (one of the original 17 rural tribes):

-

✴an inscription from the Necropoli della Banditaccia commemorates Lucius Campatius of the Voltinia; and

-

✴an inscription discovered in 1970 and published by Lidio Gasperini (referenced below, 2003, at pp. 511-5) commemorates a now-anonymous ‘L(ucius)’, who was assigned to the Voltinia.

Thus, we can reasonably assume that Egnatius was also assigned to the Voltinia, and that this was the tribal assignation of Caere from the time of its enfranchisement. There is also epigraphic evidence that suggests the assignations of three nearby centres to the Voltinia:

-

✴An inscription (CIL VI 0951, dated to 97 AD) from Rome records Lucius Sertorius Evanthus of the Voltinia, an aedile of a colony ‘C(---) N(---)’, usually completed as Castrum Novum and attributed to the Etruscan maritime colony of this name.

-

✴Annarosa Gallo (referenced below, at p. 351 and note 36) referred to a recently-discovered fragmentary inscription from Alsium, another nearby maritime colony, that records a now-anonymous member of the Voltinia.

-

✴The tribe of the prefecture of Forum Clodii (below) can be deduced from two inscriptions commemorating Quintus Cascellius Labeo:

-

•an inscription (CIL XI 3303) from Forum Clodii, which is dated to 18 AD, reproduces a decree of the decurions in which it is noted that Cascellius had undertaken to finance in perpetuity a banquet on the birthday of the Emperor Tiberius; and

-

•his epitaph (CIL VI 3510) from Rome gives his tribe as the Voltinia.

I think that the ‘alternative hypothesis’ is more likely to be correct: the Voltinia was probably the tribe assigned (for whatever reason) to viritane settlers from Rome on land confiscated from Caere in 273 BC. On this model:

-

✴a prefecture would have been established at Caere as the seat of a prefect who administered the legal affairs of viritane and perhaps colonial citizen settlers, as soon as their numbers were sufficient to require this arrangement;

-

✴Caere itself would have been assigned to the Voltinia at the unknown date of its enfranchisement, which might well have post-dated the Social War.

Colonies in Etruria after the Conquest

Latin Colony at Cosa (273 BC)

Livy (‘Periochae’, 14) recorded the foundation of the colony of Cosa in 273 BC. We know that this was a Latin colony because Livy (‘Roman History’, 27: 9 - 27:10) included it among the 12 (out of 30) extant Latin colonies that did not refuse to meet their military obligations to Rome in 209 BC. (This was the only Latin colony in Etruria that was founded by the Romans after the latin War). Pliny the Elder’s account of the centres of this stretch of coast in the Augustan seventh region included:

-

“... Cosa of the Volcientes, founded by the Roman people ...”, (‘Natural History’, 3: 8)

This suggests that the colony was sited on virgin land that had been confiscated from Vulci, presumably in 279 BC: if so, then is our earliest record of the utilisation of the Etruscan territory that had been confiscated at around this time, according to Elizabeth Fentress and Phil Perkins (referenced below, at pp. 378-9):

-

“Cosa occupied a virgin site on a promontory between two fine natural harbours ... It dominates the coast from a hill rising some 110 m above the sea ... We do not know much about the initial colony ... Certainly its walls, in splendid polygonal masonry, were built in this period. These exploit the defences provided by the natural terrain of the hilltop, encircling 14 hectares ... .”

Unfortunately, two of the things that we do not know about the original colony are:

-

✴the number of colonists who were enrolled here; and

-

✴the size of the initial land allotments.

Edward Salmon (referenced below, at p. 38) pointed out that the number of initial colonists at those broadly contemporary Latin colonies for which the information is known is in the range 4,000-6,000. He noted that Cosa received 1,000 new colonists in 197 BC to replace numbers lost in the intervening period (see below) and suggested that this made the archeologists’ estimate of 2,500 original colonists seem low (since the need for reinforcement of 40 % seems excessive). He therefore suggested that the figure of 4,000 was perhaps more likely. He observed that:

-

“Whatever the original total, it seems likely that many of them lived on their [allotted land] holdings, perhaps miles away from Cosa [itself]. Its territory was large and could easily provide for them.”

Saskia Roselaar (referenced below, 2011, at paragraph 28) gave an interesting account of the way in which the colonists interacted with their local neighbours:

-

“Archaeological evidence suggests that a number of radical changes took place immediately after the conquest and the foundation of the colony [of Cosa]. Most of these point to an active attempt by the Romans to exclude local inhabitants from the colony, making it likely that, in this case, the traditional image of a Latin colony - with expulsion of local population to marginal areas - is accurate to some degree. The local inhabitants seem to have moved, on their own accord or by order of the Romans, to marginal areas. This is attested by the fact that some settlements located mainly to the north and east of the centuriated territory ( e.g. Telamon, Ghiaccioforte, and Poggio Semproniano) remained in use and even became larger, while new settlements emerged in these areas as well.”

The new colony might have protected the surrounding ager publicus. However, it was not optimally sited for this function, and no colonies were needed for this purpose on the land recently confiscated from Caere and Tarquinii. Furthermore, the location of Cosa strongly suggests an important role in maritime defence: as Edward Salmon (referenced below, at p. 79) observed:

-

“As the Pyrrhic War was drawing to a close, Carthaginian naval power [was becoming] menacing.”

Fall of Volsinii (264 BC)

The Periochae record that Rome finally defeated the Volsinians in 264 BC. Fortunately, other writers (Paulus Orosius; and John Zonaras, drawing on Cassius Dio) also record this tragic event, which is described in detail in the page on the ancient history of Volsinii/ Orvieto. It seems that, in response to an uprising by their slaves, the nobles of Volsinii sought the help of Rome. The Consuls of 265 BC, Quintus Fabius Maximus Gurges and Lucius Mamilius Vitulus duly marched on Volsinii , but Fabius Maximus was killed as he attempted to take the city. The Romans then besieged it, and it fell to the Consul Marcus Fulvius Flaccus in 265 BC. He razed it to the ground and settled its pro-Roman citizens on another site, Volsinii Nova, which was probably near modern Bolsena.

The fasti Triumphales record that the Marcus Fulvius Flaccus was awarded a triumph in 264 BC for his victory over the “Vulsinienses”. He also seems to have destroyed the Fanum Voltumnae, the federal sanctuary of the Etruscans, which was almost certainly located just outside the city. He ‘called’ to Rome the presiding deity, Veltune, whom the Romans called Voltumna or Vertumnus, thus marking the end of Etruscan independence.

Destruction of Volsinii (264 BC)

Etruscan Volsinii was almost certainly located on the site of modern Orvieto, which rises on a cylindrical tufa cliff that would have controlled a vast territory in the plain below. It seems that the Romans agreed a foedus (treaty) with Volsinii after defeating them in 279 BC: thus, according to Cassius Dio (as summarised by John Zonaras):

-

“In [265 AD], the Romans] made an expedition to Volsinii to secure the freedom of its citizens [i.e. the noble faction that had appealed for their help in suppressing a slave revolt]; for they were under treaty obligations to them”, (‘Roman History’, 10 - search on “Volsinii”).

Cassius Dio also described how the Romans besieged Volsinii , which was eventually forced to surrender in 264 BC. The consul, Marcus Fulvius Flaccus, then:

-

“... razed the city to the ground; the native-born citizens, however, and any servants who had been loyal to their masters, were settled by him on another site””, (‘Roman History’, 10 - search on “Volsinii”).

The “fasti Triumphales” record that Flaccus as awarded a triumph in the following year for his victory over the “Vulsinienses”.

-

At this point, the history of Etruscan Orvieto effectively ended: there are no significant Roman remains on the site of Orvieto. The surviving population was moved to the ‘new’ Volsinii, at modern Bolsena, some 20 km to the southwest, on the shores of what became know as the lacus Volsiniensis, which might originally have been part of the territory of the Etruscan city. Livy had recorded a series of meetings of the ancient Etruscan Federation at the fanum Voltumnae in the period 434-389 BC but he never specified its location. However, Propertius, in an elegy that took the form of a monologue delivered by a statue of Vertumnus in Rome, had this statue insisting:

-

“[Although] I am a Tuscan born of Tuscans, [I] do not regret abandoning Volsinii’s hearths in battle” (‘Elegies’ 4.2).

Scholars reasonably assume that the fanum Voltumnae had been located in the territory of Volsinii, and that a cult statue of Voltumnus/ Vertumnus that had adorned it had been ritually called to Rome after the sanctuary itself was destroyed in 264 BC. Thus, the events at Volsinii in 264 BC marked not only the end of an ancient Etruscan city: they made manifest the end of anything resembling a confederation of independent Etruscan city states.

Ancient Latin colonies at Sutrium and Nepete protected Rome

Treaties agreed with Camerinum (310/9 BC); Ocriculum (308 BC); and the Picenti (299 BC)

Latin Colony of Narnia founded in 299 BC

40 year truces agreed with Arretium, Perusia and Volsinii in 294 BC

Lands of the Sabines and Praetuttii confiscated in 290 BC

Latin colony of Hadria and citizen colony of Castrum Novum founded in ca. 290 BC

Citizen colony of Sena Gallica founded in ca. 290 BC (Livy) or 283 BC (Polybius)

Read more:

Vermeulen F., “The Urban Landscape of Roman Central Adriatic Italy”, in:

De Light L. and Bintliff J. (editors), “Regional Urban Systems in the Roman World, 150 BCE - 250 CE” (2020) Leiden, at pp. 188–216

Fentress E. and Perkins P., “Cosa and the Ager Cosanus”:, in

Cooley A. (editor), “Companion to Roman Italy”, (2016) Chichester

Torelli, M., “The Roman Period”, in:

Thomson De Grummond N. and Pieraccini L. (editors), “Caere”, (2016) AustinTX, at pp 263–70.

Bruun C. “Roman Government and Administration”, in:

Bruun C. and Edmondson J. (editors.), “The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy”, (2015) New York, at pp. 74-98

Colivicchi F., “After the Fall: Caere after 273 B.C.E.”, Etruscan Studies, 18:2 (2015; )178-99

Rich J., “The Triumph in the Roman Republic: Frequency, Fluctuation and Policy”, in:

Lange C. and Vervaet J.(editors), “The Roman Republican Triumph: Beyond the Spectacle”, (2014) Rome, at pp. 197-258

Lepore G., “La Colonia di Sena Gallica: un Progetto Abbandonato?” , in:

Chiabà M. (editor), “Hoc Quoque Laboris Praemium: Scritti in Onore di Gino Bandelli”, (2014) Trieste, at pp. 219- 42

Rosenstein N., “Rome and the Mediterranean: 290 to 146 BC”, (2012) Edinburgh

Rossi D., “Il Territorio di Visentium in Età Romana”, in:

Di Nocera G. et al. (editors), “Archeologica e Memoria Storica: Atti delle Giornate di Studio (Viterbo 25-26 Marzo 2009)”, (2012) Viterbo, at pp. 289-310

Fronda M., “Polybius 3.40, the Foundation of Placentia and The Roman Calendar (218–217 BC)”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 60:4 (2011) 425-57

Roselaar S., “Colonies and Processes of Integration in the Roman Republic”, Melanges de l'Ecole Francaise de Rome: Antiquite, 123:2 (2011) online

Gallo A., “M. Herennius M. f. Mae. Rufus (ILLRP 441) e la Tribù dei Coloni di Alsium”, in:

Silvestrini M. (editor), “Le Tribù Romane: Atti della XVIe Rencontre sur l’Épigraphie (Bari 8-10 Ottobre 2009)”, (2010) Bari, at 349-54

Roselaar S., “Public Land in the Roman Republic: A Social and Economic History of Ager Publicus in Italy, 396 - 89 BC”, (2010) Oxford

Bispham E., “From Asculum to Actium: The Municipalisation of Italy from the Social War to Augustus”, (2008) Oxford

Sisani S., “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

Uncini F., “La Viabilità Antica nella Valle del Cesano”, (2004) Monte Porzio

Brennan T. C., “The Praetorship in the Roman Republic”, (2000) Oxford

Brennan T. C., “M’. Curius Dentatus and the Praetor's Right to Triumph”, Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 43: 4 (1994), 423-39

Mason G., “The Agrarian Role of Coloniae Maritimae: 338-241 BC”, Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 41:1 (1992) 75-87

Knapp R., “Festus 262L and Praefecturae in Italy", Athenaeum, 58 (1980) 14-38

Harris W., “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

Salmon E, “Roman Colonisation under the Republic”, (1970) New York

Ross Taylor L., “The Voting Districts of the Roman Republic: The 35 Urban and Rural Tribes”, (1960) Rome

Broughton T. R. S., “Magistrates of the Roman Republic: Volume 1: 509 BC - 100 BC”, (1951) New York

Return to Site Map: Romans