Empires of Mesopotamia:

Akkadian Empire (ca. 2300 - 2200 BC)

Main Page: Akkadian Empire (2300-2200 BC)

Topics

Empires of Mesopotamia:

Akkadian Empire (ca. 2300 - 2200 BC)

Main Page: Akkadian Empire (2300-2200 BC)

Topics

Sargon’s Conquest of Elam

As Daniel Potts (referenced below, at p. 92) observed:

“The history of what has often been called the ‘first world empire’ is generally well known, and the qualitative and quantitative differences between the short-lived hegemony of successive city-states during the Early Dynastic period and the new political, bureaucratic and religious structures created by Sargon of Akkad have been examined in detail in recent years: after subduing both the north and the south of Mesopotamia and setting himself on the path towards the creation of an empire, Sargon turned his attention to the east. In Mesopotamia, each king named a particular year of his reign after an important event that had taken place in the course of the preceding year and [it is extremely significant that]no fewer than three [sic] of Sargon’s four extant year names (see this list in the CDLI website) commemorate his eastern conquests”

Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993, at p. 8) argued that:

✴the ‘year in which Sargon destroyed Uru'a’ (year ba/bb in CDLI, above) related to his defeat of the city of Arawa (a city that was referred to as the ‘bolt of Elam’ in the later ‘Hymn B: Ishbi-Erra and Kindattu’, which suggests that it was located on the western fringes of Elam); and

✴the ‘year in which Sargon destroyed Elam’ (year c: Elam = nimki ) probably referred to Sargon’s subsequent defeat of Susa and its region.

The inscription on a ‘victory’ statue of Sargon at Nippur (known from an Old Babylonian copy, RIME, 2:1:1:1, P461926) described him as:

“Sargon, king of Agade; bailiff (mashkim) of the goddess Ishtar; king of Kish/ the world; anointed priest of the god An; king of the nation (lugal kalam-ma); chief governor of [the god] Enlil (ensi2-gal den-lil2)” , (lines 2-11).

The text then recorded his conquest of Uruk, Ur, Eninmar, Lagash and Umma in southern Mesopotamia, after which:

“... Enlil gave to him [the rest of] the territory from the Lower Sea (Persian Gulf) to the Upper Sea (Mediterranean): [throughout this territory, only] citizens of Agade are governors (ensi2): [even]:

✴Mari [to the northwest]’ and

✴Elam [to the southeast];

serve Sargon, the king of the nation”, (lines 68-86 - see also the translation by Marlies Heinz, referenced below, at p. 76, note 15).

As Heinz observed:

“By removing the local élites in the conquered cities, Sargon secured political control over the occupied territories once his military actions were over.”

Thus, we might reasonably assume that, after his conquest of Elam, Sargon installed his own Akkadian ‘ensi‘ as its new governor (or viceroy).

Two other inscriptions (known from other Old Babylonian copies from Nippur) contain important details relating to Sargon’s conquest of Elam and and Parahshum (Elam’s eastern neighbour:

✴The first text (RIME, 2:1:1:8: P461933), which was on a ‘victory’ monument, began by explicitly naming Sargon as:

“... king of the world (and) conqueror of Elam and Parahshum”. (lines 1-7).

This was followed by a curse on anyone moving the inscription and then by 18 captions, each of which would have identified an image: for example, Caption 2 (lines 25-32), which reproduced lines 1-7, would obviously have accompanied an image of Sargon himself. We learn from other captions that:

•Sargon captured at least two commanders from Elam:

-Luhishan, son of Hishibrasini, king of Elam (lugal elamki - see Caption 5, lines 38-41); and

-Sanam-Shimut, governor of Elam (ensi2 Elamki - Caption 4, lines 35-7); and

•took booty from at least three Elamite cities:

-Arawa (Caption 3, lines 33-4);

-Awan, which (as we shall see) must have been relatively close to Susa (Caption 15, lines 64-5); and

-Susa (Caption 18, lines 72-3); and also

•captured three commanders from Parahshum:

-Dagu, brother of the king of Parahshum (Caption 9, lines 49-51); and

-two generals (shagina) of Parahshum:

‣Ulul (Captiion 8, lines 46-8); and

‣Sidga’u (Caption 16, lines 66-8).

✴The second text (RIME, 2:1:1:9: P461935), which was on a votive object that had been dedicated to Enlil, contained only eight explanatory captions:

•three of these related to Sargon’s Elamite captives:

-Hishibrasini, king of Elam (Caption 7, lines 42-4);

-Luhishan, son of Hishibrasini, king of Elam (Caption 4, lines 31-4); and

-Sanam-Shimut, now described as general of Elam (shagina Elamki - Caption 3, lines 28-30); but

•only one related to a commander from Parahshum: general Sidga’u (Caption 2, lines 25-7).

The most important conclusions to be drawn from this second copy for our current purposes are that Sargon’s Elamite captives included Hishibrasini, king of Elam, as well his son, Luhishan (who was presumably his designated heir at this time.

Since it is unlikely that Luhishan and Sidga’u were both captured in the same two consecutive battles, we might reasonably assume that these two texts related to the same campaign.

As we shall see below, during a subsequent campaign in this region, Sargon’s son, Rimush, captured another enemy commander at a place:

“... between (the cities of) Awan and Susa, by the Qablitum river”, (RIME, 2:1:2:6: CDLI, P461952, lines 33-42).

This suggests that Awan was close to Susa: if so, then the battle described above was fought close to Elam’s western border. (Although Parahshum was also defeated in this battle, there is no surviving evidence that Sargon fought on its territory).

Awan and the Awan King List

Awan and Shimaski king lists from Susa,

now exhibit as Sb. 17729 in the Musée du Louvre (image from the museum website)

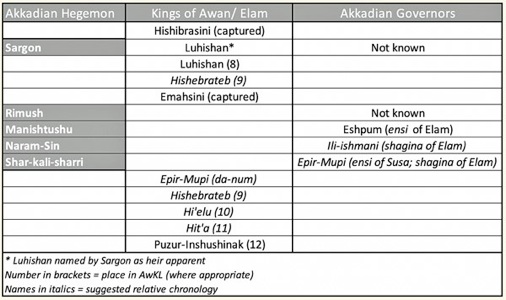

As we have seen above, Sargon claimed to have captured Hishibrasini, king of Elam, and his son, Luhishan, in a battle that was fought near the western border of Elam and affected the cities of Arawa, Awan and Susa. However, on the evidence of an inscription known as the Awan King List (AwKL), it is at least possible that Hishibrasini would have described himself, not as ‘king of Elam’, but as ‘king of Awan’.

To take this suggestion further, we now need to look more closely at the AwKL in some detail. The only evidence for a list of this kind is provided by the Akkadian inscription illustrated above, which is on the obverse of what Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, at p. 38) characterised as:

“... a clay tablet from Susa that can be dated on the basis of its script to the period ca. 1800-1600 BC. The first part of the tablet gives a list of twelve personal names (without regnal years or genealogy) which are summarised by the rubric ‘twelve kings of Awan (LUGAL.MESH sha a-wa-anki)’. The 8th [name], lu-uh-hi-ish-sha-an, is almost certainly a variant spelling of the royal name Luhishan found in a royal inscription of Sargon [see above]”.

A potential problem with this identification is the fact that Sargon had captured Luhishan while he was still only heir apparent. However, the possibility that he survived his capture should not be discounted:

✴as we shall see, a ‘Sidga’u, general of Parhshum’, whom Sargon captured in the same campaign, was apparently captured again in a similar campaign waged by Sargon’s son, Rimush; and

✴the fact that Rimush had to recapture Elam suggests that Sargon had subsequebtly beed driven out, quite possibly by Luhishan.

Another of kings named in the AWKL can also be identified from other sources: Puzur-Inshushinak, the 12th and last king in the list (whose reign is discussed below):

✴in all of the surviving inscriptions in which he was described as a king (all of which came from Susa), he was specifically styled as ‘king of Awan’; but

✴he was also documented by Ur-Namma, the first king of the Ur III dynasty, in ca. 2100 BC, but this time as ‘king of Elam’.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 179) argued that these disparities in geographical terminology:

“... practically assure that ‘Awan’ is a native correspondent of the [Akkadian] ‘Elam’, both terms describing roughly the same geographical area and, during the periods ... , the same political organism.”

In other words, on this hypothesis:

✴while Sargon regarded Awan as a city on the western border of the kingdom of Elam (which extended eastwards as far as Parahshum);

✴Luhishan (and presumably Hishbrasini) would have regarded this stretch of territory as the kingdom of Awan.

Some scholars have argued that Hishibrasini can also be identified in the AwKL: for example, Matthew Stolper (referenced below) argued that the name ‘Hishibrasini’ is a variant of Hishepratep (hi-she-eb-ra-te-eb), the 9th name in the list. It is obviously unlikely that Luhishan ruled before his father, but this could simply mean that one or other of the sources was inaccurate (perhaps due to scribal error). However, other scholars disagree with this identification: for example, having reviewed the previous scholarship, Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 23) concluded that:

“The identification of:

✴Hishibrasini, known from the ... Sargon inscriptions as the father of Luhishan; with

✴Hishebrateb, [the 9th king in the AwKL];

remains doubtful, [in view of] both ...

✴the form of the name: [Hishibrasini ≠ Hishebrateb]; and

✴the reversed order of filiation: [Luhishan, son of Hishibrasini ≠ Hisheprateb, son of Luhishan, as implied by the AwKL].”

However, Hishibrasini’s probable omission from the AwKL does not necessarily mean that he never ruled Awan: it is possible that the compiler of the list:

✴excluded Hishibrasini because he had been deposed by Sargon; but

✴included Luhishan because he had survived his captivity and gone on to drive Sargon from Awan and recover the throne.

Sanam-Shimut

As we have seen, Sargon’s captive Sanam-Shimut was described:

✴as ensi of Elam in RIME, 2:1:1:8; and

✴as shagina of Elam in RIME, 2:1:1:9.

The only other things we know (or can reasonably deduce) about him are that:

✴he had a securely Elamite name; and

✴he was clearly subservient to Hishibrasini (whom Sargon understood to be lugal of Elam).

The second of Sanam-Shimut’s titles, ‘shagina of Elam’ is unproblematic: he was clearly on a par with Ulul and Sidga’u, each of whom was styled as shagina of Parahshum. Thus, the likelihood is that this was a senior military rank (and hence the usual translation as ‘general’). More difficult is the fact that he was also styled (apparently in the same campaign) as ensi of Elam..

To take this further, we need to look at the wider evidence for the significance of the title ‘ensi’ at about this time. Aage Westenholz (referenced below, 2002, at p. 29) observed, in the period before the reign of Sargon, the rulers of the then-independent Sumerian city-states could be styled as either lugal or ensi, albeit that the terms were not freely interchangeable: for example, at Lagash:

“... Urukagina (ca. 2340) styled himself:

✴ensi of Lagash , as his predecessors had done, during the first two years of his reign; but then

✴changed his title to lugal of Lagash and counted his regnal years once again from that event on.

In other words, the difference between being ensi of Lagash and being lugal of Lagash was to him obvious and important enough to merit a renewed year count; but to us it is totally opaque.”

As it happens, we also know something about the use of the title at Elam and Parahshum at around the time of Sargon. conquest:

✴The inscription RIME, 2:1:1:8: P461933 (above) recorded two of the men captured during Sargon’s campaign against Elam and Parahshum as:

• Zina, ensi of Huzi... (lines 56-8); and

• Hidarida-x, ensi of Gunilaha (lines 59-61).

However, this is unproblematic, since they might well have been the rulers of independent cities allied to Elam and Parahshum.

✴The inscription RIME, 2:1:1:1, P461926 (above) records that Sargon gave the title ensi to the men whom he appointed as viceroys in the territories that he had subjugated, and, as we shall see, Eshpum, a later Akkadian viceroy, was indeed styled ‘ensi’ of Elam.

I find it difficult to see what could have been meant by Sanam-Shimut’s title ‘ensi of Elam’ when he was clearly subordinate to Hishibrasini, ‘lugal of Elam’. He could have been Hishibrasini’s ‘first minister’ (as well as his general), although it is unclear to me that Sargon would have regarded a king’s first minister as an ‘ensi’. I think that, in the case of the case of RIME, 2:1:1:8, we should rather rely on our old friend ’scribal error’ and assume that the scribe of RIME, 2:1:1:9 was correct when he styled Sanam-Shimut as ‘shagina of Elam’.

Akkadian Hegemony over Elam after Sargon

Rimush, son of Sargon

As noted above, it seems that Rimush, the son of Sargon, was obliged to return to the fray against Elam and Parahshum. The relevant source here is another Old Babylonian copy on the Nippur Sammeltafeln (RIME, 2:1:2:6: CDLI, P461952), which is based on a ‘royal’ inscription on a statue of Rimush. On this occasion, there were apparently two separate battles:

“Rimush, king of the world, was victorious in battle with Abalgamash, king of Parahshum. Further, Zahara and Elam had assembled in the centre of Parahshum for battle, but he was (again) victorious. ... Further, he captured Emahsini, king of Elam, and all the [...] of Elam. Further, he captured Sidga’u, the shagina of Parahshum and then he captured Sargapi, shagina of ZaÌara, in between (the cities of) Awan and Susa, by the Qablitum river. ... Furthermore, he conquered the cities of Elam, and destroyed their city walls, and he tore out the roots of Parahshum from the land of Elam. [And so, Rimush, king of the world, (now) rules Elam (as) the god Enlil had disclosed (in an omen)”, (lines 1-67).

As noted above, although the site of Awan has yet to be discovered, the phrase ‘between (the cities of) Awan and Susa, by the Qablitum river’ (at lines 37-41) indicates that Awan and Susa were relatively close to each other. Other surviving inscriptions indicate that, after his conquest of Elam and Parahshum, Rimash dedicated booty from Elam at:

It seems that Rimush defeated King Abalgamash before the armies of Zahara and Elam reached Parahshum, and that Rimush then concentrated on restoring Akkadian hegemony over Elam:

•he seems to have captured Emahsini in the second battle; and

•as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 186) observed, the subsequent reference to the destruction of of a number of Elamite cities suggests that he then campaigned in the Elamite highlands (although, again, there is no specific mention here of Anshan).

Rahim Shayegan (referenced below, at p. 261) included King Emahsini of Elam in his list of Elamite rulers. This is surely correct, but again we should add that he would have styled himself king of Awan: his omission from the AwKL might well be the result of the fact he had either submitted to Rimush or died as his captive.

Manishtushu, son of Sargon

Manishtushu’s Conquest of Anshan

No complete examples of Manistushu’s royal inscriptions survive, although:

✴fragments of what seems to have been a ‘standard’ inscription are known from a number of surviving statue fragments (as summarised by Melissa Eppihimer, referenced below, Table 1, at p. 367); and

✴more complete versions of the original (as summarised by Melissa Eppihimer, referenced below, Table 4, at p. 369) are known from:

•two scribal copies from Nippur, one of which is on the Sammeltafeln (CBS 13972) from Nippur mentioned above) and

•another scribal copy from Ur.

The composite version of this standard inscription (RIME 2:1:3:1; CDLI P461968) begins:

“Manishutushu, king of the world: (after he had) conquered Anshan and Sherihum, ... (his) ships cross the Lower Sea (Persian Gulf) ”, (lines 1-12).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 187) observed that the stable conditions that followed Rimush’s campaigns had evidently:

“... enabled Manishtushu to expand Akkad’s political and commercial influence further east ... [The] amphibious expedition [that followed Manishtushu’s conquest of Anshan and Sherihum] ... resulted in the capture of 32 ... cities [of Makkan, in what is now Oman and Abu Dhabi].”

Although we hear no more about Anshan in our surviving sources for some 200 years, we might reasonably assume that, given its apparent strategic importance to Manishtushu, it was incorporated into the Akkadian province of Elam at this time.

Eshpum, Governor of Elam

Objects from Susa with inscriptions recording Eshpum, now in the Musée du Louvre

Left: votive statue dedicated by Eshpum to Narundi (Sb. 82);

Right impression made by Eshpum’s seal (Sb. 6675)

Images from the museum website

The continuation of Akkadian hegemony over Elam is evidenced by two Akkadian inscriptions from Susa that refer to an Akkadian official called Eshpum (mentioned above) during the reign of Manishtushu:

✴the inscription (RIME 2:1:3:2001; CDLI P461975) on the back of a statue that was found in excavations in the area of the Ninbursag temple on the Acropole (now Sb. 82 in the Musée du Louvre) indicates that Eshpum, the servant of Manishtushu, king of Kish/ the world, had presented a statue of himself as an offering to Narunte (Narundi); and

✴the text (MDP. 14,4; CDLI P216807) carried by Eshphum’s seal (now Sb. 6675 in the Musée du Louvre) identifies him as the Akkadian governor of Elam (ensi2 Elamki).

Although these finds indicate that Susa was an important city within the Akkadian province, the dearth of archeological evidence from elsewhere in the province precludes an estimation of its relative importance at this time.

The location of the discovery of the votive statue of Eshpum is significant: Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, at p.182) observed that it was found under the temple of Ninhursag, in a shrine that probably:

“... predates the temple of Ninhursag and corroborates the existence (and importance) of a Narundi cult at Susa since at least the time of Eshpum ... ”,

Statues of Manishtushu at Susa

Melissa Eppihimer (referenced below, at p. 367) identified five fragments of statues of Manishtushu in the Musée du Louvre that are of relevance to the present discussion:

✴two (in Table 1) that bear original lines from Manishtushu’s ‘standard’ inscription:

•Sb. 51 (lines 15-25 and 47-59); and

•Sb. 15566 (lines 16-19); and

✴three (in Table 2) that bear Elamite inscriptions recording that the Elamite king, Shutruk-Nahhunte had brought them as booty (in the 12th century BC) and re-dedicated them to Inshushinak:

•Sb. 47 + Sb. 9099, brought to Susa from Akkad;

•Sb. 49, brought to Susa from Eshnunna; and

•Sb. 50, brought to Susa, possibly from Akkad.

It is possible, although by no means certain, that Sb. 51 and/or Sb. 15566 belonged to a statue that was originally at erected at Susa, which (if it could be confirmed) would add to the impression that Susa was indeed an important part of the Akkadian province of Elam at the time of Manishtishu.

Naram-Sin, Son of Manishtushu

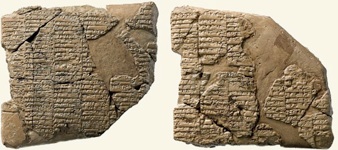

So-called ‘Treaty of Naram-Sin, from Susa, now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 8833)

A ‘royal’ inscription of Naram-Sin that is known from two Old Babylonian copies (translated as a composite as RIME 2:1:4:25: CDLI, P462023) described him as:

“Naram-Sin, king of Akkad, commander of the world ... and of:

✴the land of Elam, all of it, up to Parahshum; and

✴the land of Subartum, up to the Forest of Cedar”, (lines 1-10).

Another inscription (translated as a composite as RIME 2:1:4:2005: CDLI, P462005) on a number of stone mace heads of uncertain provenance (one of which is now in the israel Museum) recorded a dedication of the mace in question to the god Ilaba by:

“Naram-Sin, the mighty, king of the four quarters, conqueror of Armiinum, Ebla and Elam” (lines 4-7).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at pp. 187-8) suggested that these inscriptions offers some support for the claim made in later literary sources that Elam had participated in the ‘Great Revolt’ against Naram-Sin and that (like all of the rebel territories) it had subsequently been re-conquered.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 189) also drew attention (at p. 189) to the supporting evidence for Naram-Sin’s continuing hegemony over Elam provided by the inscription (MDP 11: 88; EKI 2; CDLI, P480691) on the clay tablets illustrated above, which is usually referred to as the ‘Treaty of Naram-Sin’. The Musée du Louvre notes (see Sb. 8833) characterise this as:

“The oldest surviving diplomatic text, which was ‘written’ in [old] Elamite and transcribed into Akkadian [cuneiform]. At the start, the gods of Elam are recorded as guarantors of the treaty, and this is followed by the declaration that:

‘Naram-Sin’s enemy is my enemy, and Naram-Sin’s friend is my friend’", (my translation of what was originally a translation into French of lines 3: 10-16 by Vincent Scheil, see MDP 11, referenced below).

However, Steinkeller (as above) drew attention to the enormous linguistic difficulties presented by this text and reproduced (at his note 22) the opinion of Friedrich König (referenced below - he transliterated the inscription as EKI 2) that a complete translation of the text is ‘nicht zu denken’ (out of the question). Thus, Steinkeller reasonably argued that the exact function of the ‘document’ remains unknown: all we can really say is that that:

✴it starts with the invocation of a number of gods, the majority of whom are Elamite, including, for example, Inshushinak (dnin-szuszin), who appears at line 1: 8 and again on seven occasions); and

✴the name of Naram-Sin (na-ra-am-dsuen) appears at least ten times.

As he pointed out, there appears to be no corresponding references in the text to either:

✴the most important Akkadian gods; or

✴a named Elamite ruler;

which somewhat undermines the ‘treaty’ hypothesis. Nevertheless, the discovery of this text at Susa at least confirms Naram-Sin’s complete control of Susa.

(Note that the two stamped bricks (Sb 14724-5 = IRS 1) from Susa that were previously assigned to Naram-Sin should probably be re-assigned to the Ur III king Shulgi - see below).

Naram-Sin seems to have been the first king to use these titles, and many examples of this usage survive: for example, as we have seen, he styled himself on one occasion as:

“... the mighty king of the four quarters, conqueror of Armanim, Ebla and Elam”, (RIME 2:1:4:2005: CDLI, P462005, lines 4-7).

This was by no means an isolated example: he used similar titulary in many of his other inscriptions, including a number that related to his suppression of the Great Revolt’: for example, he is recorded in an inscription on a (now fragmentary) statue from Akkad that subsequently found its way to Susa (which is now Sb. 52 in the Musée du Louvre) as:

“Naram-Sin, the mighty king of the four quarters, victor in nine battles during one year”, (RIME 2:1:4:13: CDLI, P461993, lines 1-8).

Ili-ishmani

Ili-ishmani is recorded in the Akkadian inscription (RIME 2:16:3:1: CDLI P214852) on an axe from Susa (now in the Musée du Louvre, Sb. 14243) as dubsar (scribe) and shagina mati Elamki (military governor ? of Elam). Daniel Potts (referenced below, Table 4.7, at p. 97) dated this artefact to the end of the reign of Naram-Sin or the start of the reign of his successor, Shar-kali-sharri (see below).

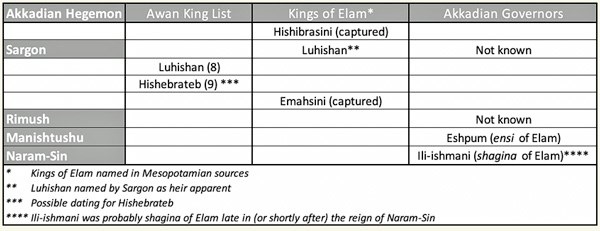

Akkadian Hegemony over Elam: Conclusions

The table above summarises my proposed scenario for the governance of Awan/Elam in the period of (albeit intermittent) Akkadian hegemony. I argued above that:

✴both Hishibrashini and Emahsini were kings of Awan, but that they were omitted from the AwKL because they had each been captured and deposed by an Akkadian invader; and

✴Luhishan (and, possibly, Hishebrateb) ruled as King of Awan before Emahshini.

Throughout this period, Awan/Elam extended from Arawa in the west to the border with Parahshum in the east. I argued above that:

✴Manishtushu incorporated Anshan into the Akkadian province; and

✴it was possibly during his reign that Susa began to emerge as one of the more important of its cities.

Puzur Inshushinak and the Awan King List

In the sections above, we have followed Puzur-Inshushinak’s career as he progressed (in the eyes of his Susian subjects) through the following series of titles:

✴ensi of Susa and shagina/ shakkanakkku of Elam (in the Akkadian inscriptions on a number of other inscribed objects including Sb. 55 and 157); and

✴after his important victory at Huposhan/ Hupsana and his subsequent receipt of the submission of the neighbouring king of Shimashki:

•king of Awan (in the LE inscriptions on the steps Sb. 139, 140A and 155);

•mighty king of Awan (in the Akkadian inscription on the step Sb. 151, which was probably duplicated on Sb. 150, 157, 18452 and 18455); and

✴probably after his victories in the Diyala region and, in particular, his conquest of Akkad:

•mighty king of Awan and of the four quarters (in the Akkadian inscription on the step Sb. 156, which was probably duplicated on Sb 137, 149, 153, 18451, 18453, 18454 and 18458).

This raises the question of why Puzur-Inshushiunak, who had adopted the Akkadian title shagina of Elam, subsequently rejected the Akkadian title ‘king (lugal) of Elam’ in favour of ‘king of Awan’. The immediately obvious answer would be that he claimed to have recovered the kingdom of Hit’a (who would later appear as the 11th of the kings in the AwKL). However:

✴Puzur-Inshushinak is the only Elamite ruler who is known to have used the title ‘king of Awan’; and

✴the AwKL (at least in the form in which it has come down to us) was obviously compiled during or after his reign.

We therefore cannot rule out the possibility that Puzur-Inshushinak himself commissioned the original list (and that the the other men named in it blissfully unaware that they had been rulers of Awan, rather than of Elam). If so, then he might have made this choice because Awan had previously appeared in the so-called Sumerian King List (SKL, translated as a composite in CDLI: P283804): in the relevant passages:

✴when Balulu, the last of the Ur I kings, was ‘struck down’, the god-given rule of Mesopotamia was ‘carried off to Awan’ (lines 146-7); and

✴it remained there throughout the reigns of three successive (but now un-named) kings of Awan: their reigns lasted (in total) for 356 years before the kingship was seized by Su-suda, the first of the Kish II kings (lines 157-61).

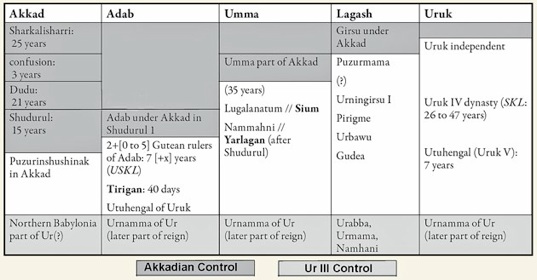

Elam in the So-Called Gutian Period

Schematic summary of the distribution of power in Mesopotamia in the period from Shar-kali-sharri to Ur-Namma

From Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, Table 36, at p. 130)

The Akkadians’ control of Mesopotamia began to unravel during the reign of Shar-kali-sharri, the son of Naram-Sin, a development that is traditionally associated with the arrival in Mesopotamia of a people known as the Gutians. Aage Westenholz (referenced below, 1999, at p. 56) observed that:

“Many year-names from Shar-kali-sharri's reign ( especially in its later part) show clearly that the Akkadian Empire was falling apart fast. [Although] Shar-kali-sharri won battles, ... they were fought ominously close to the heartland of the Empire, and his enemies were foreigners, even barbarians (Amorites, Gutians and Elamites) who somehow had penetrated deep into the Empire. That would hardly have been possible unless the governors of the outlying provinces had already defected. The Gutians had already, for some time, raided Southern Mesopotamia for cattle and had to be defeated more than once. The defections probably snowballed: once the process began, it quickly gained momentum. Lagash. [for example], declared itself independent; and Akkade was reduced to a mere city-state.”

This disintegration is reflected in the so-called Sumerian King List (translated as a composite in CDLI: P479895): the entry following that for the reign of Shar-kali-sharr asks plaintively:

“...who was king, who was nu-lugal (literally ‘not-king’)?”, (line 284).

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2021, at p. 52) it was at this time that the Gutians, whose homeland lay in the Zagros mountains, established themselves as the main political power in southern Mesopotamia: he noted (at p. 54) that they:

“... eventually established a bona fide territorial state that extended along the Tigris valley from Sippar [in the north] to Adab [in the south]. Ruling from Adab, the late Gutian kings were even able to impose their rule on the neighbouring state of Umma ..”.

An Old Babylonian tablet from contains copies of three Akkadian inscriptions from statues of the Gutian king Erridu-pizir, which have been translated as a composite at RIME 2:2:1:1; CDLI, P462080, The most interesting passage records one of captions that would have corresponded to an image of Erridu-pizir on the base of the statue:

“Erridu-pizir, the mighty king of Gutium and the four quarters, dedicated (this statue) to the god Enlil in Nippur”, (lines 94’-104’).

Here, we see Erridu-pizir styling himself after the manner of Naram-Sin. Steinkeller (as above) also noted that the Sumerian cities of Lagash and Uruk further to the south were able to regain their independence during this period of confusion: they became the dominant political powers in that region. This progressive deterioration of Akkadian power was summarised by Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 130) in their Table 36, which is reproduced above.

Example of Lagash

Aage Westenholz (referenced below, 1999, at p. 56, note 217) observed that, although the date at which Lagash declared its independence from Akkad is uncertain:

“... it must have been late in [Shar-kali-sharri’s] reign, if not after his death. Lugal-ushumgal, who had served as [(Akkadian governor (ensi) of Lagash] under Naram-Sin and Shar-kali-sharri for many years, probably remained loyal to the end ... [However], at one point, Puzur-mama was a fully independent ruler (lugal) of Lagash ...”

The career of Puzur-mama is important for our present analysis: he is described as:

✴ensi of Lagash in:

•a letter that he wrote (probably to to Shar-kali-sharri) in which he requested his help in regaining some land that Ur-Utu, who had been ensi of Ur under Naram-Sin, had allegedly been misappropriated (see Konrad Volk, referenced below, at pp. 24-5); and

•the text carried by the seal of his son, Sharu-ili (now in the Museo Profano, Museo Vaticano: 6183; P216756); and

✴lugal of Lagash in a ‘royal’ inscription from Girsu (published as a composite in CDLI: P462105).

(Note that Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p, 294, note 8) has comprehensively refuted the completion of the first line of this inscription as Puzur-Inshushinak, albeit that the second line certainly names Susa.)

Thereafter, the independent rulers of Lagash (including the redoubtable Gudea - see below) used the title ‘ensi lagashki’.

Revolt in Elam

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at pp. 190-1) observed that:

“The century or less that had elapsed between the end of Shar-kali-sharri’s reign and the advent of Ur- Namma of Ur ... [also] saw the rise of a number of independent rulers in Khuzestan and Elam”, (my changed word order).

Evidence for the start of this process is found in one of Shar-kali-sharri’ year names:

“... the year in which Shar-kali sharri brought the battle against Elam and Zahara in front of Akshak and … was victorious”, (‘year names of Shar-kali-sharri’, la).

Steinkeller argued (at p. 190) that:

“Since this battle took place on Babylonian soil (at Akshak in the Diyala Region), this must have been a defensive operation [on the part of Shar-kali-sharri]. This event is a clear indication that, ... [at some time during his] reign ... , both Khuzestan and the Iranian highlands had been freed of Akkadian [hegemony].”

He also pointed out (at p. 191) that, on purely chronological grounds, Hi’elu and Hita’a, respectively the 10th and 11th rulers in the AwKL, might have belonged to this phase of Elamite history. In other words, it is possible that the otherwise unknown Hi’elu and Hita’a used the opportunity of the Akkadians’ growing weakness to reclaim the kingship of Awan.

Epir-Mupi

The cursus honorum of Epir-mupi, an Akkadian official at Susa, probably illuminates political developments at Susa in this period: he is recorded as:

✴ensi (governor) of Susa, on an administrative tablet that is now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 18117; inscription translated as CDLI, P215581, reverse, lines 3-5);

✴shagina mati elamki (general of the land on Elam), on a seal that is now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 6672; inscription translated as CDLI, P215651); and

✴da-num (mighty), on the seasl of two of his servants:

•that of his servant Liburbeli, which is now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 6673; inscription translated as CDLI, P216814); and

•that of his servant Medu, which is now in the British Museum (BM 89119; inscription translated as CDLI, P216815).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 191) argued that:

“Given his Akkadian name, the chances are that Epir-mupi was an Akkadian appointee at Susa, whose tenure [probably] belonged to the reign of Shar-kali-sharri.”

It is possible that the title ‘ensi of Susa’ indicated that, at this time, Susa had overtaken Awan as the most important Elamite city, in which case:

✴the title ‘ensi of Susa’ would designate the civic governor of Elam, with his administrative centre located at Susa; and

✴the title ‘shagina of the land on Elam’ would designate the military governor of the province.

Epir-mupi could have held these titles sequentially: however, since both of the relevant inscriptions were found at Susa, it seems more likely that he held them concurrently (as was certainly the case for Puzur-Insushushinak - see below).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 191) argued, on the basis of the third inscription, that Epir-mupi:

“... must have become completely independent at one point, since, in the seals of his servants, he is given the title of da-num: this important title, which was coined by Naram-Sin subsequent to his deification, is proof of both Epir-mupi’s independence from Akkad and his ambitious political aspirations.”

In other words, it seems that the career of Epir-mupi, governor of Susa and Elam, had much in common with that of Puzur-mama of Lagash: each of them seems to have established his power base as an Akkadian governor before seizing power as the independent ruler of the territory that he had previously governed. However, Epir-mupi was not named as lugal of Elam in our surviving sources: neither is he named in the Awan king list (although this would have been unlikely in any case, since he was an Akkadian).

Elam in the So-Called Gutian Period: Conclusions

The table above summarises my suggested pattern of the governance of Awan/ Elam during the 200 years or so between Sargon and Puzur-Inshushinak.

Abbreviations

EKI = Friedrich König (referenced below)

MDP 11 = Jean-Vincent Scheil (referenced below)

RIME 1 = Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008)

RIME 2 = Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993)

Other references:

Steinkeller P., ‘The Sargonic and Ur III Empires’, in:

Bang P. F. et al. (editors), “The Oxford World History of Empire (Volume 2): The History of Empires”, (2021) New York, at pp. 43-72

Heinz M., “Sargon of Akkad: Rebel and Usurper in Kish”, in:

Heinz M.and Feldman M. H., “Representations of Political Power: Case Histories from Times of Change and Dissolving Order in the Ancient Near East”, (2019) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 67-86

Álvarez-Mon J., “Puzur-Inšušinak, the last king of Akkad? Text and Image Reconsidered”, Elamica 8 (2018) 169-217

Steinkeller P., “The Birth of Elam in History”, in:

Álvarez-Mon J. et al. (editors), “The Elamite World”, (2018) Oxford and New York, at pp. 177-202

Potts D. T., “The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State; Second Edition”, (2016), New York and Cambridge

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp.1-130

Steinkeller P., “An Archaic ‘Prisoner Plaque’ From Kiš”, Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie Orientale, 107 (2013) 131-5 Shayegan M. R., “Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia”, (2011) Cambridge

Eppihimer M., “Assembling King and State: The Statues of Manishtushu and the Consolidation of Akkadian Kingship”, American Journal of Archaeology, 114:3 (2010) 365-80

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Volume 1: Presargonic Period (2700-2350 BC)”, (2008) Toronto

Westenholz A., “The Sumerian City-State”, in:

Herman Hansen M., “Comparative Study of Thirty City-State Cultures: An Investigation Conducted by the Copenhagen Polis Centre”, (2002), Copenhagem, at pp. 23-42

Frayne D. R., “Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2334–2113 BC): The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Early Periods (Volume 2)”, (1993) Toronto, Buffalo and London

Westenholz A., “The Old Akkadian Period: History and Culture”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Westenholz A. (editors), “Mesopotamien: Akkade-Zeit und Ur III-Zeit”, (1999) Freiburg and Göttingen, at pp. 17-117

Volk, K., “Puzur-Mama und die Reise des Königs”, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, 82(1992) 22-9.

Stolper M. W., “Awan”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, 3:2 (1987) 113-4, see updated page on-line

König, F. W., “Die Elamischen Königsinschriften”, (1965) Graz

Scheil J-V., “Mémoires de La Mission Archéologique de Perse: Textes Élamites - Anzanites. Quatrième Série (MDP 11)”, (1911) Paris