Empires of Mesopotamia:

Kingdom of Kish in the Early Dynastic Period

Empires of Mesopotamia:

Kingdom of Kish in the Early Dynastic Period

Introduction

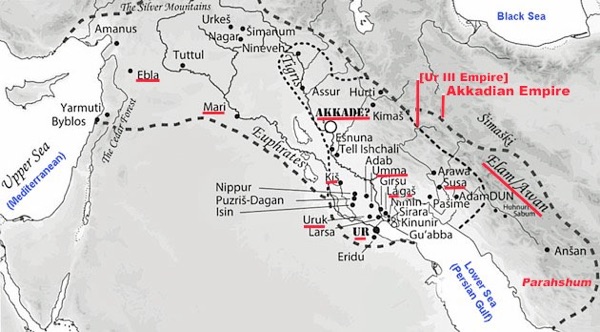

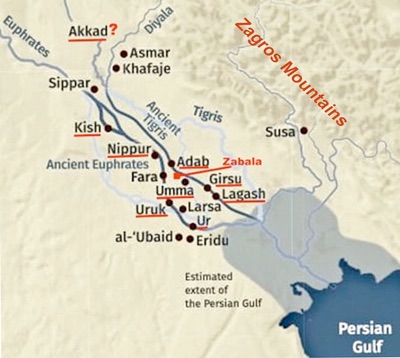

Map 1: Extent of the Akkadian and ‘Ur III[ Empires

Image adapted from Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2021, Map 2.1, at p. 69)

My additions: text in red and blue

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2021, at p. 43) observed, as far as we know, the two earliest examples of imperial experiments on record are:

✴the empire of Sargon of Akkad (ca. 2300-2200 BC); and

✴the empire of the so-called Ur III dynasty (ca. 2100-2000 BC).

He pointed out (at p. 44) that, in the 4th millennium BC, Uruk had apparently played a leading role in a commercial and trading network that involved other city-states across much of the territory that later belonged to Sargon’s empire: however, as he also pointed out, this so-called ‘Uruk Expansion’ was:

“... emphatically not an empire, ... [albeit that it] was responsible for the establishment of the trading patterns and commercial routes existing later in the very same region.”

He then suggested that:

“A more direct antecedent of the Sargonic Empire, in both time and space, was [probably] the kingdom of Kish.

This putative ‘direct antecedent of the Sargonic Empire’ is the subject of the analysis below.

Archeological Evidence for Ancient Kish

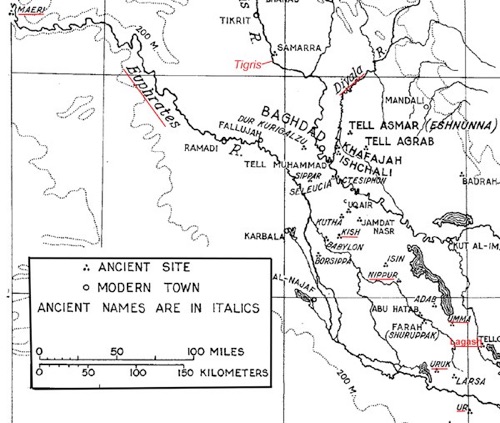

Map 2: Site of Ancient Kish

Image from Karen Wilson and Deborah Bekken (referenced below, Map 1, p. xviii): my additions in red

As Karen Wilson and Deborah Bekken (referenced below, at p. xix) pointed out, Kish was located on the floodplain of the Euphrates, some 12 km to the east of the later site of Babylon (and 80 km south of modern Baghdad). Excavations here have uncovered ancient remains under some 40 mounds that are scattered over an area of 2.4 km2. As Peter Moorey (referenced below, at p. xx) observed:

“Archaeologists and ancient historians now refer to [the totality of these mounds] as ‘Kish’, the ancient name of the city whose primary shrines lay about the standing ruin of an eroded ziggurat known locally as 'Tell Uhaimir’. Until the ancient topography of the whole area is much better known from documentary sources, ‘Kish’ suffices as a short-hand description for many closely related settlements:

✴extending back in time long before the use of writing; and

✴running down to the Mongol invasion, long after the name of Kish had passed from record.”

Karen Wilson and Deborah Bekken (referenced below, at p. xix) asserted that the Euphrates originally divided the urban area of Kish into:

✴a western area, which was dominated by [the] ziggurat found at Tell Uhaimir (probably the site of the temple of Zababa, the city-god of Kish); and

✴an eastern complex at Tell Ingharra that the ancients knew as as Hursagkalama, which was the location of an important temple of Inanna.

However, Federico Zaina (referenced below, at p. 443), in a paper reporting on his recent review of the archeological evidence from Tell Ingharra (the most extensively explored area of ancient Kish) concluded that:

”... the hypothesis that views Tell Ingharra and Tell Uhaimir as independent villages [in the 3rd millennium BC] does not seem entirely convincing.”

Having said that, there is surviving epigraphic evidence that Kish was indeed divided in some way into two urban areas in the pre-Sargonic period: in two of the inscriptions in which Sargon commemorated his victory over Lugalzagesi of Uruk (RIME 2:1:1, inscriptions 1 and 2), we read that he also:

“... altered the two sites of Kish [and] made [them] occupy (one) city”, (see, for example, RIME 2:1:1:2, CDLI P461927, lines 100-8).

Furthermore, as Stephanie Dalley (referenced below, at p. 92) pointed out, while Inanna/Ishtar eventually had temples in both locations, at least by the Old Babylonian period:

“Kish-Uhaimir and Hursagkalama-Ingharra were regarded as two separate cities as far as cults were concerned ... Zababa , [unlike Inanna/Ishtar], is never referred to as a god of Hursagkalama ... [and ancient] lists of temples also name the two cities separately.”

According to Francesco del Bravo (referenced below, at p. 303) archeological evidence (primarily from Tell Ingharra and Tell Uhaimir) indicates that:

“... between the Late Uruk and Early Dynastic IIIa-b periods, Kish underwent three stages [of urban development], each representing a significant expansion ... :

✴Late Uruk = 10.1 ha;

✴ED I = 137.2 ha;

✴ED III = 230.9 ha.

These data clearly show how, ... in the span of a few centuries, [Kish] not only [reached] an urban status but was [also] by far the largest occupied settlement in northern [Mesopotamia, at least as far as we know].”

During this period, the use of the Sumerian language in northern Mesopotamia increasingly gave way to a Semitic language dubbed ‘Akkadian’ (presumably reflecting a period of migration from the north). Aage Westenholz (referenced below, at pp. 690-1) observed that, although the textual evidence from Kish is not as extensive as one would like:

“There is sufficient textual material from ED IIIa ... to allow an assessment of the [Kishite] population around 2600 BC. The language of record of these texts is difficult to define ... [However], there are:

✴26 Sumerian names;

✴6 Akkadian; and

✴13 names of uncertain linguistic affiliation (though most of them may turn out to be Sumerian).

Bearers of Akkadian names thus made up 13.3% of the inhabitants of Kish [at this time], while well over a half were [still] Sumerians. ... During ED IIIb ..., the percentage of Akkadian names increases steadily, although the process is difficult to monitor, due to the scarcity of material.”

According to Federico Zaina (referenced below, at p. 444) the surviving archeological evidence suggests that the period of Kishite expansion:

“... ends abruptly at the end of the ED IIIb period with a violent destruction attested in several areas ... During the[subsequent] Akkadian period, Kish seems to be mostly occupied by graveyards and small squatter buildings. Its partial regeneration as a smaller centre [only begins] at the very end of the 3rd millennium BC, with the erection of a massive building ... close to the ziggurats of Ingharra.”

Early History of Kish

Evidence of the ‘Prisoner Plaque’

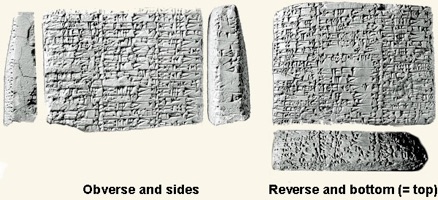

So-called ‘Prisoner Plaque; image from CDLI, P453401

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 131) characterised the inscription on the plaque illustrated above as:

“... to all appearances is the oldest historical inscription from Mesopotamia on record.”

The plaque in question, which is of unknown provenance, is now part of a private collection, although Steinkeller was able to examine high quality photographs and to access information about its material and measurements. He argued (at p. 132) that:

“On the basis of its script, the plaque may tentatively be dated to the ED II period or (although less likely) to the ED I period.”

More recently, Camille Lecompte (referenced below, at pp. 440-3) dated it to the later part of the ED II period.

The shallow relief on the front of this plaque, which depicts two standing male figures facing left, carrying bows and other objects, is relatively uninformative. However, the main body of the six-column text, which is written in Sumerian cuneiform on the reverse, is made up of a list of captives from at least 25 different locations and the number of captives from each. Steinkeller offered the following tentative translation of these final lines of the surviving text (at p. 133):

“36,000 captives

(They were assigned) to the filling of threshing floors (with grain) and the making of grain stacks

The stone (monument) fashioned in Kish

Zababa is the god of manhood”, (col. vi, lines 3’-7’).

The inscription ends on the lower right edge with the name of the scribe, Amar-SHID. Since the surviving( [incomplete) text records 28,970 captives (see p. 133), and assuming that the figure 36,000 represents the actual total, it seems that about 20% of the original text has been lost.

Steinkeller argued (at p. 132) that:

“The plaque almost certainly stems from Kish (or one of its dependencies, [as] is assured by the following data:

✴the plaque mentions Zababa, the patron god of Kish (vi 7');

✴the city of Kish is likely named in it as well (vi 6');

✴the signs, sign-values and other paleographic features of the inscription show strong connections to the early written materials from Kish and from northern [Mesopotamia] more generally ... ;

✴the [25] toponyms named in the [surviving part of the] inscription include [at least 8] that also appear in the Early Dynastic ‘List of Geographical Names’ ... [see the discussion below]; and

✴the scene depicted on the [obverse] shows similarities to an ED II inlaid frieze excavated at Kish [see his Figure 5, at p. 153].

He argued (at p. 142) that:

“As best as it can be ascertained, the plaque is a record of the prisoners of war who were acquired as booty by the state of Kish in the course of its territorial conquests. The preserved sections of the plaque name 25 conquered places, with one of them (Asha) appearing twice (i 10', ii 7'). The numbers of prisoners per toponym vary from 50 (i 15') to 6,300 (v 5'). Given the wide variation among the numbers, there is every reason to think that these are real, and not inflated, figures. Since the numbers (as preserved) add up to 28,970 captives, with a significant number of entries presently missing, it is likely that the figure of the total (36,000) is likewise a real one, though probably slightly rounded up”.

He acknowledged (at p. 144) that:

“... the plaque does not name the ruler (or rulers) responsible for these conquests and the bringing of the captives to Kish (although it is possible that his name appeared at the very beginning of the inscription, now missing). Instead, its concluding lines praise Zababa, the divine master of Kish and (fittingly) a god of war."

It seems to me that, if this ‘document’ originated in Kish (as was probably the case), then it is indeed likely that this ruler was named as the king of Kish, who (in local tradition) had been given this hallowed, god-given kingship by (or at least with the help of) Zababa.

Steinkeller suggested (at p. 143) that:

“Both the large number of localities conquered and the huge figures of captives so obtained speak against the possibility that the plaque describes the outcome of a single military campaign. Much more likely, in my view, [is the hypothesis that] we find here a cumulative record of the conquests carried out by Kish over a period of time.”

He therefore concluded (at p. 145) that the ‘Prisoner Plaque’:

“... provides priceless information about the formation and the territorial conquests of the state of Kish during the phases of the ED period. In this connection, particularly eloquent is the mention of 6,300 captives acquired in the land of Shubur (Assyria). Here, one witnesses not only the oldest occurrence of Assyria's name, but also a palpable proof of Kish’s foreign expansion. The plaque also confirms what had been suspected by some scholars (this one among them) about the early Kishite state, [particularly in relation to its putative] hegemonic and militaristic character. The figure of 36,000 prisoners of war ... recorded in the plaque is astonishing, since it was not until the advent of Sargon of Akkad and his [successors] that rulers again were able to aspire to similar military feats. Because of this, the state of Kish is considered [by these scholars to be] a forerunner of the Sargonic empire.”

Note, however, that nothing in the surviving text indicates the circumstances in which any or all of the 36,000 captives were taken. Steinkeller assumes that they had been captured during successive campaigns of conquest that had culminated in the hegemony of Kish over a huge part of northern Mesopotamia that extended at least as far north as Assyria (on the upper reaches of the Tigris). However, it is equally possible that some or all of these captives were taken in raids that were aimed primarily at the acquisition of slaves rather than territory. Furthermore, as Aage Westenholz (referenced below, at p. 697) pointed out, even if some or all of them had been taken in battle from localities that Kish had defeated, the surviving text:

“... scarcely proves the existence of a territorial state in the north, [centred on Kish], any more than [the evidence for] Eanatum’s campaigns ... [against enemies from distant cities, including Shubur, in the ED IIIb period - see the following page] prove the existence of a territorial state in the south, centred on Lagash.”

In other words, while the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ arguably confirms the ‘militaristic character’ of Kish in the ED II period, it does not offer secure evidence that the Kishites either claimed or achieved hegemony over dozens of cities, including some as far away as Assyria to the north and/or the Diyala valley to the northeast.

Evidence of the ‘List of Geographical Names’ (LGN)

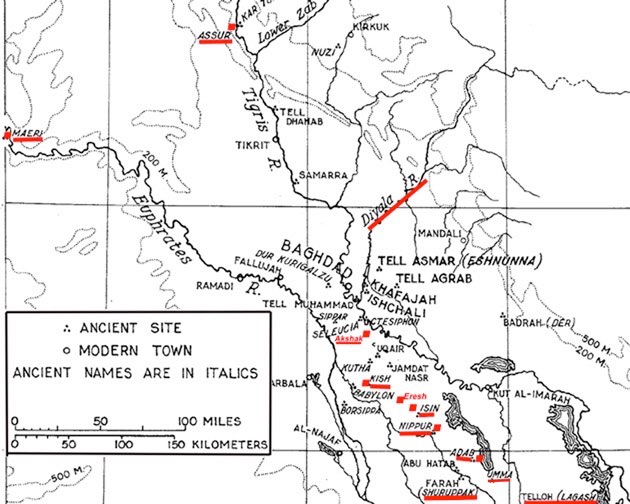

Map 3: Kish and the LGN

Image from Karen Wilson and Deborah Bekken (referenced below, Map 1, p. xviii): my additions in red

Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 65) observed, this list of localities, which is known from a number of fragments from Abu Salabikh [probably ancient Eresh - see Nicholas Postgate, referenced below, at pp. 200-2]:

“... can be reconstructed on the basis of a completely preserved duplicate from Ebla [in modern Syria] and other recently published duplicates of unknown provenance. Only a tiny fraction of the 289 toponyms [in the list] can be identified and related to places attested in administrative texts from other archives. [According to Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1992) they] belong to two groups:

✴[the toponyms of the first group were] located in the north of Babylonia; and

✴[those] in second group [were located] in the Transtigridian region (between the Tigris and the Zagros mountains to the east), the Zagros [themselves] and Khuzistan.”

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 148) argued that:

“Since the LGN was known already in the ED IIIa period, [the likely date of the Abu Salabikh text], it must reflect a considerably earlier situation.”

He also argued (at p. 147) that:

“... Kishite scribes were apparently the first to use cuneiform to record historical inscriptions (as demonstrated by the ‘Prisoner Plaque’) ... They also compiled new lexical texts, ... [including the LGN].”

In other words, he argued that:

✴the list of captives in the ‘Prisoner Plaque’; and

✴the list of localities in the LGN;

were both compiled at Kish in the ED II period.

Combined Evidence of the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ and the LGN

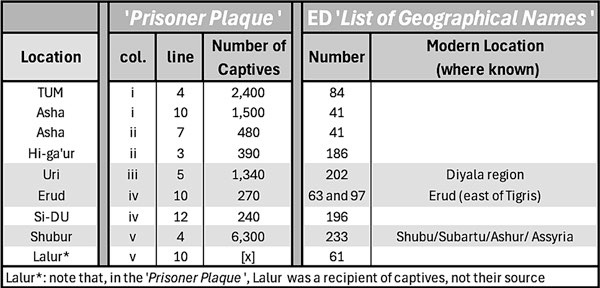

Table 1: Locations mentioned in both the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ and the ED ‘List of Geographical Names‘

See Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 132 for places named in both the \Prisoner Plaque’ and the LGN

and p. 142 for those of them that can be reasonably securely identified

As set out on Table 1 above:

✴8 of the 25 localities mentioned in the surviving text of the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ can (or can probably) also be found among the 289 localities in the LGN; and

✴3 of these 8 localities can (or can probably) be identified at known ‘modern’ locations.

Importantly, the list of captives in the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ included:

✴6,300 from Shubur/Assyria (LGN 233), on the upper reaches of the Tigris; and

✴1,340 from Uri, the region of the Diyala river.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 132) argued (citing one of his earlier papers) that the LGN:

“... represents a gazetteer of the archaic territorial state of Kish.”

Furthermore, on the basis of this hypothesis, he further argued (at p. 148) that, by the time that the now-unknown king of Kish commissioned the ‘Prisoner Plaque’, he exercised hegemony over:

“... the entire territory of northern Babylonia, most northern section of southern Babylonia (Nippur, Isin and Eresh) and large portions of of the Diyala Region. The Kishite expansion also affected Assyria, on the upper reaches of the Tigris ...”

I assume that the point here is that:

✴Nippur (LGN 177) and Isin (LGN 70), along with Sharrakum (LGN 167, which was probably close to Adab) seem to have marked the southern boundary of the territory covered by the LGN;

✴Eresh (Abu Salabikh), which was only 20 km northwest of Nippur, was the find spot of surviving fragments of the LGN; and

✴two location at the periphery of the territory covered by the LGN:

•Uri (the Diyala region), which lay to the east; and

•Shubur (Assyria), which to the north:

were actually named in the ‘Prisoner Plaque’.

Aage Westenholz (referenced below, at pp. 697-8) pointed out that Steinkeller’s conclusion that:

“... ‘the state of Kish embraced the entire territory [covered by the LGN]’ is really a bit of circular reasoning:

✴because the LGN enumerates cities in those regions, it is assumed to be a gazetteer of the Kishite state; and

✴on the strength of that assumption, it proves the extent of that state !”

He also pointed out (at pp. 691-2) that:

✴only six relevant administrative documents from Kish (all of which date to the ED IIIa period) survive and, of these:

•although one (Ashmolean 1928-435, P222333) names Asha (LGN 41), which (as we have seen) also appears twice in the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ (as the source of 1500+489 captives);

•none of the other 5 of these documents names a single locality that appears in either the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ or the LGN; and

✴the only fragment of a lexical list of geographical names from Kish itself (Ashmolean 1931-145, P451600), which dates to the of ED IIIa period:

“... appears to belong to a series hitherto unknown.”

He concluded (at p. 692) that:

“... there is only slight support from Kish for the idea that the LGN is a gazetteer of the Kishite kingdom. In fact, the very idea that [the LGN] is a ‘gazetteer’ of anything is problematic: where do we find parallels to that? Furthermore, a good number of the place names in the LGN are also mentioned in the administrative documents from Fara.”

Early History of Kish: Conclusions

It does seem likely that the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ was commissioned at Kish by a ruler (almost certainly a king) who had a precocious understanding of the potential ‘propaganda value’ of royal inscriptions and a military capability that allowed him to secure large numbers of captives who could be put to work at Kish. Moreover, it seems that these captives were seized from places across a swathe of territory that extended as far as Shubur in the north, the Diyala region to the east and the area east of the Tigris. However, nothing in this text suggests that Kish exercised hegemony over any of the settlements within this territory: indeed, the fact that the text refers to the people brought to Kish as ‘captives’ suggest (at least to me) that they were seized during raids on territories that Kish did not control.

Since it cannot be established beyond doubt that the LGN was written in Kish and/or served as a ‘gazetteer’ of places over which Kish exercised hegemony, it is arguably of little value in establishing the extent of a putative ‘territorial state’ of Kish. Furthermore, since. as Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 65) observed, the absence of southern place names in this list is striking, even if it was accepted as the gazetteer of the putative ‘territorial state’ of Kish, one would have to conclude that the area of Kishite hegemony at this time did not extend to any significant extent into Sumer.

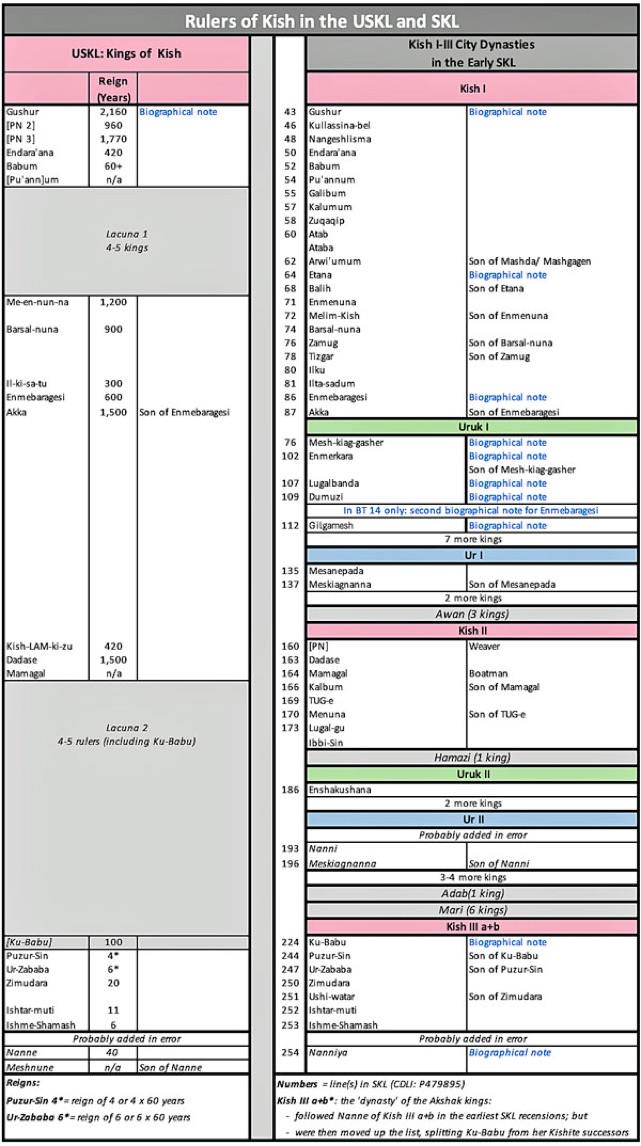

Kish in the Ur III Sumerian King List (USKL)

Surviving part of the tablet containing the Ur III recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL):

these images of the tablet (which is in a private collection) is adapted from CDLI: P283804

Introduction

Before Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003) published the inscription on the tablet fragment illustrated above, the Sumerian King List (SKL) was known only from a number of surviving fragments of recensions from the Old Babylonian period (ca. 1900-1600 BC): the corpus of these OB texts now contains 24 mostly fragmentary inscriptions and is conveniently accessible as a composite at CDLI: P479895. Although these texts have been extensively studied since 1923, when the so-called Weld-Blundell Prism (now in the Ashmolean Museum) was published, Steinkeller’s publication of the USKL paved the way for a much deeper understanding of the processes by which these important (but perplexing) documents evolved. Importantly, Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, forthcoming) is about to publish a critical edition of all the known recensions (including the USKL), together with a full analysis of this process of textual evolution.

Piotr Steinkeller (as above) provided:

✴a transliteration of the surviving text of the USKL; and

✴an initial commentary that remains fundamental.

Little more has been published to date, although a transliteration and photographs are available on line at CDLI: P283804. The original text was inscribed on part of a clay tablet of unknown provenience, which was (as it still is) in a private collection. It is arranged in three columns on each side of this tablet fragment (with that on the reverse sometimes continuing onto the bottom). About half of the original text is missing but, since the opening and closing lines survive, we know that:

✴it begins (at obverse, col. 1, line 1) with the claim that:

“After kingship was brought down from heaven, Kish was king. In Kish, Gushur ruled for 2,160 years”, (see the translations by Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, 2010, at p. 231 and Gösta Gabriel, 2023, referenced below, at p. 247); and

✴it ends with:

•the name of Ur-Namma, the founder of the ‘Ur III’ dynasty, who had reigned for 18 years (reverse, col. 3, lines 21-2); and

•the scribe’s dedication of his handiwork to the divine Shulgi, his king (who was Ur-Namma’s son and successor).

Steinkeller argued that, since Shulgi was given a divine determinative here, this text must have been compiled at some time between:

•his 20th regnal year (the approximate date of his deification); and

•his 48th regnal year (the approximate date of his death).

In other words, the USKL was compiled in ca. 2074-2047 BC and thus pre-dates any other known recension by more than 150 years.

Kings of Kish in the USKL

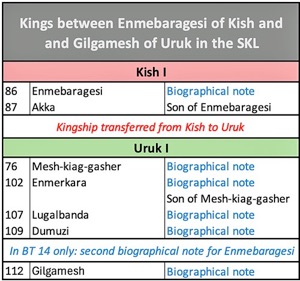

Table 2: Kings of Kish in the USKL and the SKL

USKL names based on Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, forthcoming, Table 5.2):

SKL entries based on CDLI: P479895

Piotr Steinkeller (as above) established (at p. 274) that:

✴almost all of the 21 king listed on the obverse of the surviving USKL tablet could be identified as kings of Kish in the SKL; and

✴the original must have begun with an unbroken list of about 30 Kishite kings from Gushur to Meshnune, the son of Nanne.

However, in the period between the compilation of the USKL and that of the earliest known SKL recensions, this originally unbroken list was ‘punctuated’ by the inclusion of other ‘city dynasties’ (see Table 2 above).

Steinkeller further argued (at p. 282) that, since neither Shulgi nor any other ruler from southern Mesopotamia would have originated a king list that began with 30 kings of Kish who had held the god-given kingship from time immemorial, we are left with:

“... only one possible agency for whom the USKL’s vision of history ... would have been an acceptable one: ... [the kings of the Akkadian dynasty would] have had an obvious interest in promoting the idea that Kish remained the seat of kingship from time immemorial down to Sargon’s own day.”

In other words, Shulgi’s scribe probably extended and elaborated a list that had been compiled for a king of Akkad. Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023) provided further support for this hypothesis and then argued (at p. 244) that:

“It is unlikely that the historical Old Akkadian rulers invented the long list of Kishite kings [themselves]. It is much more probable that they copied an existing list of rulers and so continued the Kishite historiographical tradition, including the celestial origin of the city’s power and its extremely long first reign. Accordingly, the first recension of what would become the [USKL and then the SKL] was most likely written in Kish before ca. 2350 BC.”

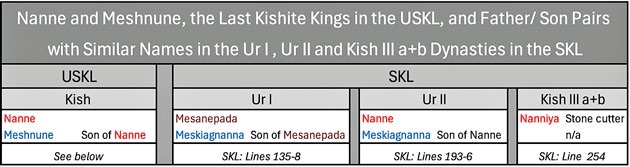

The Problem of Meshnune, the son of Nanne

Table 3: Father/son pairs with similar names in the USKL and the SKL

(See Gösta Gabriel, referenced below, forthcoming, Chapter 6.2.21.5 and Table 6.50 for

a more detailed analysis of the possible transmission of these names between recensions)

Unfortunately, there is a lacuna in the surviving USKL text after the records for Nanne and Meshnune. However, in the SKL:

✴Meshnune is not recorded; and

✴Nanne is transmitted as Nanniya, the stone cutter, who reigned for 7 years before:

“Kish was struck down with weapons [and] the kingship was carried away to Uruk, [where] Lugalzagesi was king”, (CDLI: P479895, lines 254-60).

For this reason, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) reasonably argued that Meshnune must have been the last Kishite king in the USKL since:

“...no more rulers of Kish are listed in the SKL [after Nanne/ Nanniya].”

Of course, this leaves the question of why Meshnune is one of very few Kishite kings in the the USKL who was not recorded in any of the known SKL recensions (see below).

There is another surprising thing about Meshnune: he is one of only two Kishite kings among the 21 recorded in the surviving USKL text who is given a patronymic (the other being Akka, son of Enmebaragesi - see below). Interestingly, according to Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, forthcoming, Chapter 6.2.21.3 and Table 6.48), 7 of the 8 Kishite kings known to have been added to the USKL list in the SKL (marked by horizontal arrows in the table) were designated as the son of the king listed above them. On this basis, we might reasonable argue that:

✴the putative original Kishite king list eschewed patronymics; and

✴both Meshnune and Akka (discussed below) were additions to this list (probably, but not necessarily, inserted by Shulgi’s scribe).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 278) offered a possible explanation for Meshnune’s appearance in the USKL and his later deletion from the SKL, starting with the observation that:

“The pair [Nanne and Meshnune, son of Nanne] appears to have been given a double (or perhaps a treble) life in the SKL ...:

✴[they] almost certainly also ended up as the first two rulers of Ur II ...; and

✴it may further be speculated that they are also identical to [the first two rulers of Ur I]”, (see Table 3 above).

This prompted him to ask, rhetorically:

“Is it possible, therefore, that Nanne and Meshnune are, in fact Mesanepada and Meskiagnuna of Ur, whom the USKL classified as Kishite rulers because Mesanepada held the title [king of Kish]? If so, SKL’s decision to reclassify them as the rulers of Ur would be fully justified.”

In other words, perhaps:

✴Nanne/ Nannya was an abbreviation of Mesanepada, a historical king of Ur who is known from a surviving inscription ((RIME 1.13.5.2, P431204) to have also claimed the title king of Kish; and

✴Meshnune was an abbreviation of Meskiagnanna.

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, forthcoming, see, for example, Table 6.50) presented a more detailed analysis in which (in all but one of the Old Babylonian recensions, which he labelled XP:1):

✴Nanne of the USKL reappeared as the Ur II king of that name (see line 193); and

✴Meshnune of the USKL reappeared as:

•Meskiagnanna, son of Mesanepada in the Ur I king list (see lines 137-8); and

•Meskiagnanna, son of Nanne in the Ur II king list (see line 196).

This supports the suggestion above, at least in the case of Meshnune: he was indeed probably added to an original list of Kishite kings, erroneously as it turned out, by Shulgi’s scribe.

Kish in the USKL: Conclusions

At the end of his paper on the ‘Prisoner Plaque’, Piotr Steinkeller(referenced below, 2013, at p. 151) mused on the problem of the historicity of the SKL (and, by implication, of the USKL). As he observed:

“Particularly puzzling here is the nearly total disjunct between the names of Kishite kings recorded in the list and those surviving in the [surviving] historical records.

✴Of all the Kishite kings named in the list, only one, Enmebaragesi [discussed below] is documented independently.

✴On the other hand, there are several northern bearers of the title who do not appear in the list. The most conspicuous among them is Mesalim, whose dedicatory inscriptions survived at Adab and Girsu [see below]. Given the fact that these and other inscriptions that he had left behind were well known to the ancients, omission from the list is simply astonishing.

This raises a question as to the nature information that was used (in Sargonic times, or was it in the Ur III period ??) by the original compilers of the list with regard to the kings of Kish. I, for one, can offer no confident explanations and only note them as a problem.”

I wonder whether we might simplify this problem to some extent by splitting the surviving Kishite list in the USKL into two parts:

✴Gushur to Dadase, all of whom had unbelievably long reigns (implying that they originated in the world of mythology); and

✴Ku-Babu to Ishme-Shamash, who (if we allow Ku-Babu the luxury of a 100 year reign) are all at least potentially historical figures.

More specifically, we might hypothesise that:

✴the ‘mythological’ part of the USKL Kishite king list evolved on the basis of what Gösta Gabriel dubbed:

“... the first recension of what would become the [USKL and then the SKL] was most likely written in Kish before ca. 2350 BC; and

✴the ‘quasi-historical’ part of the USKL Kishite king list evolved from Gabriel’s putative Akkadian recension, which was probably written at the behest of Sargon or one of his dynastic successors.

In that case, we can suggest a partial answer to Steinkeller’s specific question as follows: perhaps this ‘disjunct’ between:

✴the Kishite kings listed in the USKL; and

✴those who are recorded in our surviving ‘historical’ sources;

arises because there were arguably three distinct sources for the former:

✴a list of early Kishite kings from Gushur to Dadase that was mostly taken from Kishite mythological tradition;

✴additions to this list that were made by Shulgi’s scribe in an effort to include what he regarded as ‘historical’ figures:

•Enmbaragesi and his son, Akka; and

•Nanne and his son Meshnune; and

✴a quasi-historical or at least traditional list of Kishite rulers from Ku-Babu to Ishme-Shamash.

Perhaps the most important question in the present context is why Shulgi based his case for the legitimacy of his rule as ‘mighty man, king of Ur, king of the lands of Sumer and Akkad’ in part on their ‘descent’ from the mythical kings of Kish.

The cultural/religious context in which this claim was made is probably beyond modern comprehension. However, we can certainly use the surviving USKL text from Gushur to Ku-Babu as evidence that the prestige of the kingship of Kish survived long after Kish itself had descended into political oblivion. However, the prestige that is evident in this source is based simply on the ‘fact’ that, as stated in the opening lines, when kingship descended from heaven, it descended on Kish.

.

Early ‘Historical’ Kings of Kish

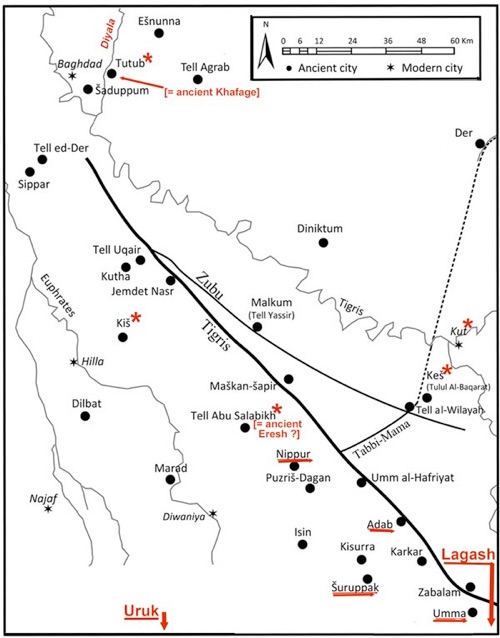

Map of Mesopotamia during the 3rd millennium BC

From the website of the Lagash Archeological Project: my additions in red

As Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, at p. 5) observed, one of the things:

“... complicating the historical picture in ED times is the fact that the title ‘lugal kish’ of ED royal inscriptions, while clearly referring in some cases to actual kings of Kish, ... seems, at other times, to be an honorific epithet meaning something like ‘king of the world’.”

In this section, I discuss four rulers whom I argue were or might have been ‘actual kings of Kish’ in the early dynastic period:

✴Enmebaragesi, whom Frayne also accepted as an ‘actual kings of Kish’;

✴Akka, who is not known from any royal inscriptions and is thus outside Frayne’s database;

✴Mesalim, whom Frayne assigned to his Chapter 8: ‘Rulers with the Title ‘King of Kish’ whose Dynastic Affiliations are Unknown’; and

✴Lugalnamnirshum, of whom Frayne was apparently unaware.

Enmebaragesi, King of Kish

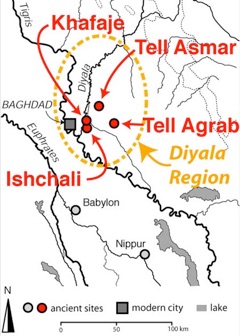

Map of the Diyala Basin: image from the website pf the ‘Diyala Project’’ (University of Chicago)

Epigraphic Evidence for Enmebaragesi

Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, at p. 55) observed that:

“The first king of Kish for whom we have any inscriptions is Enmebaragesi.”

More specifically, Frayne identified this first king of Kish as:

✴the ‘Mebaragesi’ whose name appears on a fragment of a stone bowl from Khafayah (ancient Tutub) in the Diyala valley (RIME 1:7:22:1; CDLI. P431026), although only this single word survives; and

✴the ‘Mebaragesi, king of Kish’, whose name appears on a fragment of a large stone (alabaster) bowl of unknown provenience (RIME 1:7:22:2; CDLI, P431027).

Both of these fragments are (or were) in the Iraq Museum, and the second of them:

“... [was apparently] ‘confiscated at Kut,’ and bears the museum number IM 30590.”

The fact that these inscriptions were on stone bowls might be significant. For example, Nicholas Postgate (referenced below, at p. 127) observed that the generic Sumerian term for these objects is ‘bur’, and the process of making them was ‘surely laborious’ and they ‘were special’. For example:

“[A] ritual procedure which symbolised political hegemony over a city entailed the ruler making an offering in a stone bowl to the patron deity of the city. This is attested at Adab [see the section on Mesalim below] and at Nippur, and the earliest example is probably at Khafayah, where a stone bowl with the name of (En)mebaragesi ... must have come from a temple”.

He also observed (at p. 168) in relation to both of these inscriptions that:

“The practice of a ruler making a presentation to a temple in a stone bowl therefore has a long history ...”

I return to the subject of the putative dedication of stone bowls to the patron deities of cities by kings of Kish in order to to symbolise their hegemony over them in the final concluding remarks on this page.

Gianni Marchesi (referenced below, 2015, at p. 152) started his list of kings of Kish with Enmebaragesi on the basis of the second of these inscriptions, which he dated to ED I (albeit that he assigned the first to another now-unknown individual and dated it to ED III). Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 149 and note 70):

✴rejected Marchesi’s late dating for the inscription of ‘Mebaragesi’ from Khafayah in the Diyala region; and

✴observed that a third early inscription (RIME 1:7:40:1; CDLI, P431028), which is on a fragment of a stone vessel from Tell Agrab that records a now unknown king of Kish, provides further evidence for the Kishites’ connections with the Diyala region at this time.

He therefore argued that:

“... the discoveries of the inscriptions of:

✴Enmebaragesi [at Khafajah]; and

✴an unidentified king of Kish [at] Tell Agrab ... ;

are convincing indicators of the Kishite presence in the Diyala region.”

He offered these observations in support of his hypothesis (put forward at p. 148) that the testimony of the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ and the ‘List of Geographical Names’ (discussed above) indicates that, at this time, the putative :

“... state of Kish embraced [a large tract of Mesopotamia as far south as Nippur] and large portions of the Diyala Region.

Enmebaragesi in the Sumerian King Lists

As we have seen in Table 2, Enmebaragesi is the only king listed in the surviving part of the USKL between Gushur and Ku-Babu who is arguably ‘historical’ (albeit that the 600 year reign that he is given in that list is not). I therefore suggested that he was a later addition to what was an original list of kings of Kish that derived from Kishite mythical tradition. Although the date of this putative addition is not known, it is surely significant that Enmebaragesi also featured prominently in Sumerian literary tradition at the time of Shulgi: as Gösta Gabriel (as above) pointed out, we read in a praise poem of Shulgi known as ‘Hymn O’ that:

“Shulgi, the good shepherd of Sumer, praised his brother and friend, lord Gilgamesh [with these words] ... :

‘Mighty in battle, destroyer of cities, smiting them in combat.

You, [Gilgamesh], drew your weapons against the house of Kish.

You captured [the bodies of ?] its seven heroes.

You trampled underfoot the head of the king of Kish, Enmebaragesi.

You brought the kingship from Kish to Uruk", (lines 49-60, see also the translation by Ludek Vacin, referenced below, at p. 224).

As Vacin observed, these lines are redolent of the ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae used in the SKL (including at least the later part of the USKL). Thus, it is tempting to conclude that Enmebaragesi was added to the USKL list by Shulgi’s scribes.

Evidence for the longevity of Enmebaragesi’s position in Sumerian literature is found in the surviving SKL recensions (P479895), in which we read that:

“[At Kish], Enmebaragesi, who defeated the land of Elam, was king: he ruled for 900 years.” (lines 83-6)

Thus,

✴he now received a biographical note that might indicate that he had driven off raiders from ‘Elam’ (generally assumed to refer at this time to the Zagros Mountains), presumably because they threatened his territory in the Diyala Valley; and

✴his reign was increased from the 600 years in the USKL to 900 years.

Furthermore, the so-called ‘Tummal Chronicle’, which was broadly contemporary with the SKL and seems to have made use of similar sources, claims that:

“Enmebaragesi built the temple of Enlil named uru-na-nam [in Nippur] and his his son, Akka ... brought Ninlil into [the shrine] at Tummal. Then, [the shrine] at Tummal fell into ruins for the first time.”, (‘Tummal Chronicle’, lines 106).

Table 4: Enmebaragesi in the ‘BT14’ recension of the SKL

Interestingly Enmebaragesi received an unprecedented second biographical note in a single surviving SKL recension from Nippur that is usually referred to as ‘BT14’, which was re-published by Jacob Klein (referenced below). The textual context is summarised in Table 4 above. This second note has been variously translated: for example:

✴“He (i.e., Dumuzi) was taken as booty [i.e., as a prisoner of war] by the (single) hand of Enmebaragesi”, (see Jacob Klein, referenced below, at p. 78); or

✴“He (i.e., Gilgamesh) took (away) the booty from the hands of Enmebaragesi”, (see Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, 2010, at pp. 241-2).

More recently, Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, forthcoming, at Chapter 6.4.6.2 and note 137, who labelled BT14 as NiI:1a) argued that it was inserted at this point in the text in order to indicate that Enmebaragesi of Kish had controlled Uruk in a (presumably brief) period between the reigns of Dumuzi and Gilgamesh. He:

✴rejected the translation of Gianni Marchesi;

✴accepted that of Jacob Klein (his Übersetzung 1); and

✴offered an alternative translation (his Übersetzung 2):

“(Uruk) became booty [i.e., was sacked] through the hand of Enmebaragesi”, (my translation of the German of Gösta Gabriel).

Thus, although the precise translation is still debated, it seems that the compiler of BT14 was at pains to draw attention to the fact that Enmebaragesi had sacked Uruk at some time between the reigns of Dumuzi and Gilgamesh.

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, forthcoming, at Chapter 6.4.6.2) pointed out that the compiler of BT14 attempted to incorporate the literary tradition relating to the conflict between Uruk and Kish (evidenced, for example, in ‘Hymn O’) into the SKL, but that this approach clearly did not achieve widespread acceptance. This was probably because it created an internal chronological inconsistency, since:

✴the new note made Enmebaragesi a contemporary of Dumuzi and Gilgamesh; while

✴in the surrounding text (which contains an account of the early kings of Uruk, replete with biographical notes), the Enmebaragesi and Gilgamesh were separated by five other rulers who reigned for a total of 2,670 years.

Akka, Son of Enmebaragesi in Sumerian Literary Tradition

Unlike his putative father, Akka is not known from surviving royal inscriptions. He is, however, known from the Sumerian poem ‘Gilgamesh and Akka’ (see the translation by Andrew George, referenced below, at pp. 100-4). George observed (at p. 99) that:

“This ... is the shortest of the [five known] Sumerian tales of Gilgamesh and also the best preserved. ... It differs from the other four ... in having no obvious counterpart in the Akkadian [‘Epic of Gilgamesh’].”

As he also noted (at p. xxi), these five Sumerian poems:

“... were probably first committed to writing under the [Ur III dynasty]. whose kings felt a special bond with Gilgamesh as a legendary hero whom they considered their predecessor and ancestor. ... The texts that we have, although known almost entirely from ... copies [of the 18th century BC], are very probably directly descended from master copies ... [that King Shulgi placed] in his Tablet Houses. ... Even so, it is entirely possible that the poems stem ultimately from an older, oral tradition.”

We read in ‘Gilgamesh and Akka’ that:

✴when envoys of Akka, the son of Enmebaragesi, came from Kish to make unspecified demands on Uruk, Gilgamesh persuaded the Urukeans to fight rather than to submit (lines 1-47);

✴Akka laid siege to Uruk (49-82); and

✴when Gilgamesh appeared on the walls of Uruk in all his glory:

•the army of Uruk emerged from the city and defeated the terrified Kishites; and

•Gilgamesh took Akka prisoner (lines 83-99).

So far, so predictable. However, the ending to the story is rather unexpected:

✴Gilgamesh recognised the captive Akka as his overlord and acknowledged an earlier occasion on which Akka had saved his life by helping him to flee from an unidentified danger (see lines 100-6);

✴Akka transferred Uruk to the charge of Gilgamesh, but asked him to repay his debt of honour (lines 107-10); and

✴Gilgamesh duly redeemed this ‘debt’ by freeing Akka and allowing him to return to Kish (line 1113).

As Dina Katz (referenced below, at p. 14) observed, there are thus two Sumerian literary traditions relating to a war between Kish and Uruk at the time of Gilgamesh:

✴in Shulgi’s ‘Hymn O’ (see above), Gilgamesh defeated Enmebaragesi (who, according to the second note in the BT14 recension of the SKL, had taken control of Uruk during the reign of Dumuzi); while

✴in the Sumerian poem ‘Gilgamesh and Akka’, Gilgamesh defeated Akka, the son of Enmebaragesi.

As she observed, this:

“... raises the question of whether:

✴[there was a single Sumerian tradition in which] Gilgamesh fought [two wars against Kish, one against Enmebaragesi and the other against Akka]: or

✴we are dealing with two different traditions about one and the same war.”

She discounted the first of these propositions, primarily because the internal evidence from the poem implies that, prior to Gilgamesh’s victory over Akka, Uruk was subject to Kish. Furthermore, she found direct support for the second proposition from the fact that ‘Hymn O’ actually reflects two of the five Sumerian poems:

✴‘Gilgamesh and Akka’; and

✴‘Gilgamesh and Huwawa’ (see the fragmentary line 95):

as she pointed out (at p. 15), the appearance of at least two independent Sumerian traditions relating to Gilgamesh in ‘Hymn O’:

“... indicates that these tales ... were already in existence in Shulgi's time, although perhaps only as an oral traditions.”

In other words, the surviving evidence arguably suggests that:

✴in early Sumerian tradition, Gilgamesh rescued Uruk from the hegemony of Kish by defeating Akka; and

✴the author of ‘Hymn O’decided to elaborate this tradition by replacing Akka by Enmebaragesi.

In addressing the likely reason for this putative substitution of Enmebaragesi for Akka, she observed (at p. 15) that:

“The reputable king of Kish was Enmebaragesi, as is evident from ...:

✴the [biographical] note added to his name in the SKL; and

✴his place as the first builder of Enlil's temple [at Nippur] in the Tummal Inscription.”

Both sources are later than [‘Hymn O’], and testify to Enmebaragesi's image as it was handed down to the Old Babylonian period. His son Akka is mentioned in these sources, but only as his successor and without special reference.”

She then argued that:

“In historical perspective, the defeat of Akka would be less impressive than the defeat of his prestigious father, who therefore served the purpose of [‘Hymn O’] far better and added to the quality of Gilgamesh's victory over Kish. Since Enmebaragesi's name was deliberately inserted to replace Akka's, the hymn does not reflect a separate tradition: the tale and the hymn are variants of one literary tradition.”

Akka, Son of Enmebaragesi in the USKL

As discussed above, Akka appears in the USKL as the son and successor of Enmebaragesi. Importantly, if we set aside Meshnune, son of Nanne, both of whom were probably added to the original list in error) then Akka is the only one of the 19 Kishite kings listed in the surviving part of this list who is given a patronymic.

As also discussed above:

✴Akka, son of Enmebaragesi, also appears in Sumerian poem ‘Gilgamesh and Akka’, in which he was driven from the walls of Uruk by the Urukean hero Gilgamesh but allowed to return to Kish; but

✴Dina Katz (who was writing before the publication of the USKL) reasonably suggested that, in ‘Hymn O” (in which Shulgi praised his “brother and friend”, the Urukean hero Gilgamesh), he (Shulgi) replaced Akka by the more prestigious (and historically attested) Enmebaragesi.

On this basis, we should extend this hypothesis as follows:

✴in the original Sumerian tradition, Gilgamesh liberated Uruk from the hegemony of Akka, king of Kish;

✴at the time of Shulgi:

•this original tradition formed the basis of the poem that we know as ‘Gilgamesh and Akka’, with Akka named (perhaps for the first time) as the son of Enmebaragesi);

•‘Hymn O’ was written, with Enmebaragesi replacing Akka as the king who was defeated by Gilgamesh; and

•both Enmebaragesi and Akka were added (as father and son) to the original list of Kishite kings in the USKL; and

✴in the OB period:

•compilers of the SKL recensions broke the USKL Kishite king list after the reign of Akka, announcing that Kish was then destroyed and kingship was transferred to ‘Eanna’ (the district of Uruk where the temple of Inanna was located), where Meshkiagasher, the son of the god sun Utu, was lord (see CDLI: P479895, lines 87-98);

•the compiler of recension BT14 of the USKL gave Enbaragesi an otherwise unattested second biographical note, implying that he had taken ‘Eanna’ from Dumuzi but had then been driven out by Gilgamesh; and

•both Enmebaragesi and his son Akka were included in the broadly contemporary ‘Tummal Chronicle’ (in which Enmebaragesi built the temple of Enlil at Nippur and Akka brought Ninlil into the shrine at Tummal).

Thus, we have a plausible hypothesis in which ‘King Akka of Kish’ was a purely literary figure to whom Shulgi gave ‘quasi-historic’ status by:

✴having (the probably legendary) Gilgamesh (Shulgi’s own ‘brother and friend’) defeat the historical Enmebaragesi rather than the legendary Akka; and

✴‘nodding’ to tradition by naming Akka as Enmebaragesi’s son.

However, we cannot rule out the possibility that Shulgi had epigraphic evidence in which ‘Akka, son of Enmebaragesi’ actually was named as a king of Kish.

Enmebaragesi, King of Kish: Conclusions

It seems to me that:

✴the conventional view of Enmebaragesi as the first historically-attested king of Kish is probably the correct one; and

✴the arguments made for his political influence in the Diyala valley are similarly strong, so that the suggestion that he formally exercised hegemony here cannot be excluded.

However, the biographical note in the SKL that has him defeating ‘Elam’, if it means anything at all, might mean no more than that he had occasionally driven off ‘Elamite’ raiders who threatened his territory.

His inclusion in the USKL as the father of Akka (like that of Nanne/Mesanepada as the father of Meshnune/Meskiagnanna) demands attention: as I suggested above, it is at least possible, that Shulgi’s scribe added him to the original Kishite/Sargonic list(s) on the basis of epigraphic evidence that was later also used for:

✴his biographical note in the SKL; and

✴his inclusion in the ‘Tummal Chronicle’.

That brings us to the matter of the historicity of Akka. In my view, the analyses of Andrew George and of Dina Katz discussed above are persuasive in identifying him as the opponent of Gilgamesh in Sumerian tradition, as first written down at Shulgi’s court. This allows us to assume that Akka, like Gilgamesh, was a figure taken from Sumerian myth and that:

✴the composer of ‘Hymn O’ replaced the otherwise-unknown Akka with the more prestigious (and historically attested) Enmebaragesi; and

✴the compiler of the USKL simply ‘nodded’ to the early tradition by including Akka and identifying him as Enmebaragesi’s son.

However, we cannot discount the alternative possibility that Shulgi’s scribes had access to now-lost epigraphic evidence that Akka, the son of Enmebaragesi, had indeed succeeded his father as king of Kish.

Mesalim, King of Kish

As we shall see, Mesalim is a key figure for our understanding (such as it is) of the political situation in Sumer in the early part of the ED period, not least because:

✴three of his royal inscriptions survive; and

✴he is documented in inscriptions from other, later, Mesopotamian rulers.

However, none of this body of epigraphic evidence comes from Kish and (more surprisingly) it seems unlikely that he was among the 30 or so kings of Kish that were listed in the USKL:

✴he is certainly not among the 19 names that survive in this recension; and

✴nor is he listed in any of the later recensions of the SKL.

I suggested above that this omission might simply have arisen because the list of Kishite kings that formed the basis for the USKL list from Gushur to the now-unknown ruler who preceded Ku-Babu was actually a list of mythical kings of Kish.

Mesalim’s Hegemony over Lagash

Mace-head of Mesalim, King of Kish (RIME 1.8.1.1; P462181), from the original Ningirsu temple at Girsu

Now in the Musée du Louvre (AO 2349), images from the museum website

The most famous of Mesalim’s surviving royal inscriptions is on a stone mace-head (illustrated above), which he dedicated to Ningirsu, the main god of Lagash, in his original temple at Girsu (the ‘religious capital’ of a political entity that already embraced both ‘Lagash proper’ and Girsu):

✴the top of the mace-head is carved with a relief of a lion-headed eagle (usually known as the Anzu bird), which, as Sébastien Rey (referenced below, at p. 176) pointed out, was already established by this period as the emblem of Ningirsu; and

✴the curved surface below it is carved with a frieze relief of six lions biting each other (which is another example of local iconography).

The inscription, which extends across two of the lions, records that:

“Mesalim, king of Kish, temple builder for the god Ningirsu, set up (?) this mace for the god Ningirsu [when] Lugal-sha-engur (was) ensi of Lagash”, (RIME 1.8.1.1; P462181).

As discussed further below:

✴Mesalim clearly exercised hegemony over Lagash and Girsu; and

✴Lugal-sha-engur, the ensi of Lagash, who is the earliest-known ensi of Lagash, was presumably either:

•a governor appointed by Mesalim; or

•a local ruler who acknowledged Mesalim’s hegemony.

The earliest Ningirsu temple on this site (which is known to archeologists as the ‘Lower Construction’) almost certainly pre-dated Mesalim, although the inscription suggests that he was responsible for a significant restoration of it. Sébastien Rey (referenced below, at p. 61 and at pp. 209-10) observed that:

✴the mace was almost certainly originally housed within this archaic building; and

✴its find-spot suggests that it was subsequently ritually buried in the foundations of the temple that Ur-Nanshe (the first independent ruler of Lagash/Girsu that we know of) built over it.

In other words, it is clear that Mesalim exercised hegemony over Lagash/Girsu at some time prior to the reign of Ur-Nanshe, the founder of what we know as the first dynasty of Lagash.

Meslim’s Hegemony over Umma

Unusually, we know more about Mesalim from the royal inscriptions of later rulers (in this case, rulers of Lagash). For example, about a century after Mesalim’s rule, Eanatum, ensi of Lagash and the grandson of Ur-Nanshe) looked back on his role in the establishment of the border between between Lagash and Umma in:

✴an inscription (RIME 1.9.3.2; P431076) found on three boundary stones; and

✴a very similar inscription (RIME 1.9.3.3; P431077) found on two spheroid jars;

all of which came (or probably came) from either Girsu or Lagash. More specifically, Eanatum recorded that, after his victory in a boundary dispute Umma, he had:

✴restored the boundary stele that Mesalim had erected to mark the boundary between the respective territories, which had originally been defined by the god Enlil (see, for example, RIME 1.9.3.2; P431076, lines 4-7); and

✴in deference to the gods, he had not marched beyond the point (see, for example, RIME 1.9.3.2; P431076, lines 55’-60’).

Fortunately, we have a more complete account of these events from a royal inscription of a yet-later ensi of Lagash, Enmetena (Eanatum’s nephew): at the start of his account of his own boundary dispute with Umma, he looked back on the precedents set by Mesalim and Eanatum:

“Enlil, lugal kur-kur-a (king of all lands), ab-ba dingir-dingir-re2-ne-ke4 (father/elder of all the gods) ... demarcated the border between:

✴Ningirsu, [the city god of Lagash and Girsu]; and

✴Shara, [the city god of Umma].

Mesalim, king of Kish, at the command of Ishtaran, measured it out and erected a stele there. Ush, ensi of Umma, acted arrogantly: he smashed that monument and marched on the plain of Lagash. Ningirsu, warrior of Enlil, at his (Enlil's) just command, did battle with Umma. ... Eanatum, ensi of Lagash, demarcated the border with Enakale, the ensi of Umma. ... He inscribed (and erected) monuments at [the god-given border] and restored the monument of Mesalim, but did not cross [the border] into the plain of Umma”, (RIME 1.9.5.1; P431117, lines 1-58).

It is clear from these later testimonies that Mesalim’s authority as hegemon extended to Umma, and that his role in the establishment of the boundary between Lagash and Umma was long-remembered, at least at Lagash.

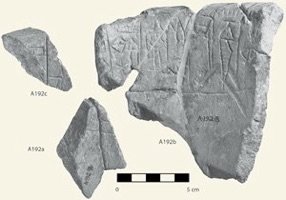

Mesalim’s Hegemony over Adab

Two inscriptions of Mesalim, King of Kish, from the Esar Temple at Adab, both now in the now in the

Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures at Chicago

Left: fragment of a stone bowl (A211: inscription RIME 1.8.1.2; P462182)

Right: three fragments from the rim of a steatite vessel (A192 a-c: inscription RIME 1.8.1.3; P431033)

Images from Karen Wilson (referenced below): A 221, from Plate 106a; A912 a-c from Plate 51

The other two surviving royal inscriptions of Mesalim come from the Esar temple at Adab:

✴one, which was found on fragments of two stone bowls, recorded that:

“Mesalim, king of Kish, sent over this bur mu-gi4 (stone bowl, used for the burgi ritual) in the Esar temple [when] Ninkisalsi (was) ensi of Adab”, (RIME 1.8.1.2; P462182); and

✴the other, which was found on three fragment of a stone (steatite) vessel, recorded that:

“Mesalim, king of Kish, beloved son of Ninhursag [dedicated this vessel] ...”, (RIME 1.8.1.3; P431033).

Although some scholars (see, for example, Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 2008, at p. 20) suggest that the Esar temple at Adab dedicated to Inanna (= Ishtar), Karen Wilson (referenced below, at pp. 73-4 and in Table 9.1, at p. 100) has shown that the archeological evidence (which includes that from Mesalim’s steatite vessel) indicates that this temple was dedicated to Ninhursag (who is sometimes named as Dingirmah). It is also evident from her Table 9:1 that the Esar probably pre-dated the reign of Mesalim. However, the most important point to make here is that:

✴Mesalim clearly exercised hegemony over Adab (as well as Lagash and Umma); and

✴Ninkisalsi the ensi of Adab (like Lugal-sha-engur, the ensi of Lagash) was presumably either a governor appointed by Mesalim or a local ruler who acknowledged his hegemony.

Lugalnamnirshum, King of Kish

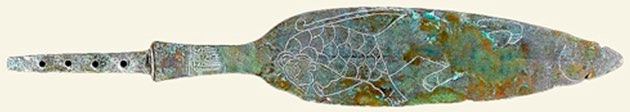

Large copper spearhead inscribed with the name of Lugalnamnirshum, king of Kish (RIME 1.8.2.1: P462183)

From the original Ningirsu temple at Girsu, now in the Musée du Louvre (AO 2675: image from museum website)

This copper spearhead, which is some 85 cm long, was found at the temple of Ningirsu at Girsu. As Sébastien Rey (referenced below, at p. 210) observed, it would originally have been fitted with an imposing shaft and displayed pointing downwards, as suggested by the relief of a standing lion on one of its surfaces (see the illustration above). The inscription on the neck of the spearhead (above the head of the lion) was only partially legible until 1994, when it was rescued from a layer of corrosion, revealing that it had been dedicated (presumably to Ningirsu) by Lugalnamnirshum, king of Kish (see, for example, Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 2008, at p. 73).

Sébastien Rey (referenced below, at p. 209) also pointed out that a number of scholars have been misled by an early, flawed description of the find-spot of this important object, which placed it in Ur-Nanshe’s temple on this site: thus. for example, Gianni Marchesi (referenced below: 2011, note 244, at p. 124; and 2015, at pp. 144-5, Uruk entry 4 and Table 1.2, at p. 142) argued that it had been dedicated by a king of Uruk who:

✴used the title ‘king of Kish’; and

✴exercised hegemony over Lagash towards the end of Ur-Nanshe’s reign and into that of his son, A-kurgal.

In fact, as Sébastien Rey (as above) pointed out, this spearhead (like the mace of Mesalim discussed above) had been dedicated in Ningirsu’s original temple at Girsu and then ritually buried in the foundations of that of Ur-Nanshe. He therefore argued (at p. 210) that Lugalnamnirshum:

“... was doubtless one of Mesalim of Kish’s successors, and, therefore, in all likelihood, another foreign overlord of Girsu [and Lagash] in the period before Ur-Nanshe ascended to power.”

Early ‘Historical’ Kings of Kish: Conclusions

Map adapted from Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2022, Map 1, at p. 5), my additions in red

City underlined in red = member of the Kiengi League

City with red asterisk also mentioned below

Geography

The map above provides the geographical background to the following analysis: in particular, the locations of:

✴Khafage (modern Tutub) and Kut, the original locations (or, in the case of Kut, the probably location) of the the surviving inscription(s) of Enmebaragesi and

✴Adab, Umma and Lagash, the original locations of the surviving inscriptions of Mesalim.

It also picks out the cities that belonged to the so-called Kiengi League in the Fara Period, which included Adab, Umma and Lagash as well as Uruk, Nippur and Shuruppak (modern Fara). Other cities mentioned below are picked out by red asterisks.

Chronology

Any attempt to draw overall conclusions from the analysis above must begin with the extraordinarily difficult question of chronology. In other words, while my effort to place these four kings of Kish in chronological order is (I hope) relatively uncontroversial, the same could not be said about the chronological gap between:

✴Enmebaragesi and Mesalim; and

✴Mesalim and the next important king of Kish, Menunsi, whom I discuss in a subsequent page.

Taking the second difficulty first: since (as I discuss in this subsequent page):

✴Menunsi is mentioned in an administrative tablet from the so-called Fara Period; and

✴other administrative documents from the same period relate to what was probably a military alliance that included the (presumably independent) city-states of Adab, Lagash and Umma;

I assume that we can be reasonably certain that Menunsi post-dated Mesalim (who exercised hegemony over all three of these city-states).

To take this further, I am going to follow both the methodology and the resulting conclusions of Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2024, Appendix 3, at pp. 22-3), who addressed the relative dating of:

✴the reigns of:

•Enmebaragesi;

•Mesalim; and

•Ur-Nanshe, who (as noted above) was, as far as we know, the first independent ruler of Lagash; and

✴the administrative documents from the Fara Period.

His key points were that:

✴a comparison of the orthography/paleography of:

•Ur-Nanshe’s texts; and

•the Fara tablets;

strongly suggests that they were ‘roughly contemporaneous’’; and

✴the orthography of a legal text from Adab (CUSAS 26, 69: CDLI, P427630), which mentions A-kurgal the son and successor of Ur-Nanshe (see A-kurgal, ensi of Lagash, at 5:5- 6:1):

“... constitutes a transitional phase between the orthography of:

•the Fara tablets and Ur-Nanshe’s inscriptions; and

•the inscriptions of Eanatum (the son and successor of A-kurgal).

He followed this by arguing that:

“This evidence forces us to conclude that the reign of Ur-Nanshe was contemporaneous with the Fara tablets. Even if this reign was slightly later than those materials (a possibility that cannot be excluded), it still firmly belonged to the ED IIIa period, as it is usually defined by the archaeologists and philologists alike. ... As for Mesalim, whose reign has traditionally been dated to ED II, this ruler must have been a predecessor of Menunsi [see above]. This dating finds support in [Mesalim’s] inscriptions, whose paleography is strikingly archaic, being comparable to those of Enmebaragesi of Kish.”

If this is accepted, then it is reasonable to consider the Kishite kings discussed in this page:

✴Enmerbaragesi (and his son Akka, if he actually was a historical figure); and

✴Mesalim and Lugalnamnirshum, both of whom pre-dated Ur-Nanshe (as discussed above);

as all belonging to a relatively short period of time before Kish ceased to exercise hegemony over Adab, Lagash and Umma.

Prestige of the Kingship of Kish in the ED III Period

As we have seen, when Ur-Nanshe built a new temple over the original Ningirsu temple at Girsu, he ritually buried the objects that Mesalim and Lugalnamnirshum had dedicated to Ningirsu in the original temple in the foundations of the new one. Interestingly, however, he treated another a much older sacred object from the original temple in a very different way: according to Sébastien Rey (referenced below):

✴this object, which was dubbed by its discoverer the ‘figure aux plumes’, was a plaque that almost certainly depicted Ningirsu wearing a feathered head entering his temple (see p. 178);

✴in his view:

“There is no doubt ... that it was originally housed in the [original temple] and was probably fashioned to commemorate [its] construction and inauguration”, (see p. 181); and

✴it was subsequently preserved in Ur-Nanshe’s new temple (see p. 284).

In short, although Ur-Nanshe arguably chose to ‘recover the past’ in his new temple, he treated the objects that the earlier hegemonic rulers had dedicated to Ningirsu in the original one with due respect. This behaviour is, of course, not unexpected, since these objects clearly ‘belonged’ to Ningirsu. However, it does imply that Ur-Nanshe recognised that Ningirsu had recognised (and, arguably, that he had instigated) the earlier Kishite hegemony over Girsu and Lagash. This impression of the acceptance of the legitamcy of the earlier hegemonic rulers is also found in:

✴the claims of Eanatum that he restored Mesalim’s boundary stele and refused to march beyond it into what he still regarded as the territory of Umma; and

✴the testimony of Enmetena that :

“Enlil ... demarcated the border between Shara [and] Mesalim, king of Kish, at the command of Ishtaran, measured it out and erected a stele there.”

Furthermore, when a later ruler of Umma, Gishakidu, (who was probably a contemporary of Enmetana - see Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, referenced below, at p. 78) restored this boundary, he described himself (inter alia) as the beloved friend of Ishtaran (RIME 1.12.6.2; CDLI, P431197, lines 13-4), which implies that he also accepted the boundary as it had been demarcated by Mesalim. In short, while it is often claimed that Mesalim had intervened as arbitrator in a boundary dispute between Lagash and Umma, it is equally possible that both sides accepted the legitimacy of Kishite hegemony and thus Mesalim’s god-given right to establish the border between them.

I wonder (and this is pure speculation) whether the three small city-states of Lagash/Girsu, Umma and Adab welcomed the hegemony of the Kishites in the ED II period, possibly because it offered protection from other directions (perhaps from ‘Elamite’ raiders who had access to the Lower Sea’ ??). If so, then we might speculate further that Kish was weakened for various reasons in the Fara Period, allowing Ur-Nanshe (for example) to assume the kingship at Girsu/Lagash in relatively peaceful circumstances.

Stone Bowls

In the section above on the surviving inscriptions of Enmebaragesi, which happen to be on stone bowls, I quoted the following passage by Nicholas Postgate (referenced below, at p. 127):

“Stone bowls were special: a ritual procedure which symbolised political hegemony over a city entailed the ruler making an offering in a stone bowl to the patron deity of the city. This is attested at Adab and at Nippur, and the earliest example is probably at Khafayah, where a stone bowl with the name of (En)mebaragesi ... must have come from a temple”.

As promised there, I now return to this important observation. As Postgate subsequently made clear (at p, 167) the evidence of the ‘ritual procedure’ of this kind attested at Adab is found on three fragment of a stone (steatite) vessel from the Esar temple at Adab, which (as noted above) recorded that:

“Mesalim, king of Kish, beloved son of Ninhursag [dedicated this vessel] ...”, (RIME 1.8.1.3; P431033).

Postgate also pointed out (at p. 168) that there is evidence from the early version of the so-called ‘Kesh Temple Hymn’ from Abu Salabikh (probably ancient Eresh) that another king of Kish participated in a similar ritual at Kesh. This version, which belongs to the ED III/Fara period was published by Robert Biggs (referenced below) in 1971: prior to that date, this hymn was known only from the Old Babylonian period. As Biggs observed (at p. 196):

“Although the Abu Salabikh copies are approximately eight centuries earlier than copies known before, there is a surprisingly small amount of deviation (except in orthography) between them.”

One of these few ‘deviations’ occurred in a passage (at lines 105-17) that describes the dedication of the temple and the role played by various priests and the king:

✴in the the OB version we read (at line 107) that:

“In the temple, the king put a stone bowl in place”; but

✴in the Abu Salabikh version, this king is identified as the king of Kish.

Biggs commented that this:

“... implies composition of the [Abu Salabikh version] at a time when Kish controlled Sumer, at least ... in the general area of which Kesh is to be located.”

Although the location of ancient Kesh has long been the subject of debate, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2022, at p. 4) noted that, following a recent discovery:

“... the religious centre of Kesh, which ... can positively be identified as one of the ten tells forming the site of Tulul al-Baqarat [about 50 km north of Adab - see the map above].”

Postgate (as above) argued (at pp. 168-9) that:

“Since we know that Mesalim ... presented stone bowls to the temple at neighbouring [sic] Adab, one cannot avoid putting two and two together and seeing this as a reflection of a royal intervention in the temple affairs of Kesh, symbolising the same statement of sovereignty as already seen at Girsu and Adab, whether it was Mesalim himself or one of his predecessors or successors who was recognised as King of Kish. Inscribed stone bowls were not an innovation of Mesalim: (En-)mebaragesi ... left his succinct inscription on at least two stone bowls.:

✴[one that was] excavated at Khafajeh... ‘ and

✴another ... [that] found its way onto the local antiquities market (IM 30590: ‘confiscated at Kut’).”

Interestingly, as shown on the map above, Kut is close to Tulul al-Baqarat, the site of ancient Kesh.

In short, it is possible that, for much of the ED I-II period Kish:

✴exercised hegemony over:

•the land along the left bank of the Tigris from Khafage to Kesh; and

•other land on the right bank that included Adab, Umma and Lagash (and perhaps also Nippur and Shuruppak ??); and

✴used this land as a buffer zone from which to protect Kish and the cities over which it exercised hegemony from ‘Elamite’ raids.

References

Gabriel G. I., "Die ‚Sumerische Königsliste’ als Werk der Geschichte: Kritische Editionsowie text-, stoff- und konzepthistorische Analyse”, (forthcoming: I would like to express my gratitude to Dr Gabriel for allowing me to read a pre-publication copy of this much-needed book)

del Bravo F., “The Diyala Region and the ‘Territorial State of Kish’”, in:

Ramazzotti M. (editor), “Costeggiando l’Eurasia: Archeologia del Paesaggio e Geografia Storica tra l’Oceano Indiano e il Mar Mediterraneo: Primo Congresso di Archeologia del Paesaggio e Geografia Storica del Vicino Oriente Antico (Sapienza Università di Roma, 5-8 Ottobre 2021)”, (2024) Rome, at pp. 297-314

Postgate J. N., “City of Culture 2600 BC: Early Mesopotamian History and Archaeology at Abu Salabikh”, (2024) Oxford

Rey S., “The Temple of Ningirsu: the Culture of the Sacred in Mesopotamia”, (2024) University Park, PA

Steinkeller P., “Campaign of Southern City-States against Kiš as Documented in the ED IIIa Sources from Šuruppak (Fara)”, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 76 (2024) 3-26

Gabriel, G. I.,"The ‘Prehistory’ of the Sumerian King List and Its Narrative Residue", in:

Konstantopoulos G. and Helle S., “The Shape of Stories”, (2023) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 234-57

Wilson K. L. and Bekken D., “Where Kingship Descended from Heaven: Studies on Ancient Kish”, Chicago IL (2023)

Steinkeller P., “Two Sargonic Seals from Urusagrig and the Question of Urusagrig’s Location’, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, 112:1 (2022) 1–10

Steinkeller P., “The Sargonic and Ur III Empires”, in:

Bang P. F. et al. (editors), “The Oxford World History of Empire (Volume 2): The History of Empires”, (2021) New York, at pp. 43-72

George A. R., “Epic of Gilgamesh”, (2020, 2nd edition) London

Lecompte C., “A Propos de Deux Monuments Figurés du Début du 3e Millénaire: Observations sur la Figure aux Plumes et la Prisoner Plaque”, in:

Arkhipov I. et al. (editors), “The Third Millennium: Studies in Early Mesopotamia and Syria in Honor of Walter Sommerfeld and Manfred Krebernik”, (2020), Leiden and Boston, at pp. 417-46

Westenholz A., “Was Kish the Center of a Territorial State in the Third Millennium?—and Other Thorny Questions”, in:

Arkhipov I. et al. (editors), “The Third Millennium: Studies in Early Mesopotamia and Syria in Honor of Walter Sommerfeld and Manfred Krebernik”, (2020) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 686-715

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2017) Boston and Berlin

Zaina F., “Tell Ingharra-East Kish in the 3rd Millennium BC: Urban Development, Architecture and Functional Analysis”, in:

Stucky R. A. et al. (editors), “Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East”, (2016) Wiesbaden, at pp. 431-46

Marchesi G., “Toward a Chronology of Early Dynastic Rulers in Mesopotamia”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 139-58

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 1-130

Steinkeller P., “An Archaic “Prisoner Plaque” from Kiš”, Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie Orientale, 107 (2013) 131-57

Wilson K. L., “Bismaya: Recovering the Lost City of Adab”, (2o12) Chicago

Vacin L., “Šulgi of Ur: Life, Deeds, Ideology and Legacy of a Mesopotamian Ruler As Reflected Primarily in Literary Texts”, (2011), thesis of the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London)

Marchesi G., “The Historical Framework (Chapter 2)” and “The Inscriptions on Royal Statues (Chapter 4)”, in:

Marchesi G. and Marchetti N., “Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia”, (2011) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 97-128 and pp. 155-85 respectively

Dalley S. M., “Old Babylonian Prophecies at Uruk and Kish”, in:

Melville S. and Slotsky A. (editors), “Opening the Tablet Box: Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Benjamin R. Foster”, (2010) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 85-97

Marchesi G., “The Sumerian King List and the Early History of Mesopotamia”, in:

Biga M. G. and Liverani M. (editors.), “Ana Turri Gimilli: Studi Dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer da Amici e Allievi”, (2010) Rome, at pp 231-48

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Vol. 1: Presargonic Period (2700-2350 BC)”, (2008) Toronto

Klein J., “The Brockmon Collection Duplicate of the Sumerian King List (BT14)”, in:

Michalowski P. (editor), “On the Third Dynasty of Ur: Studies in Honor of Marcel Sigrist”, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Supplemental Series 1 (2008) at pp. 77–9

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-292

Katz D., “Gilgamesh and Akka”, 1 (1993) Groningen

Frayne D. R., “Early Dynastic List of Geographical Names: American Oriental Series 74”, (1992) New Haven, CT

Moorey P. R. S., “Kish Excavations (1923-1933)”, (1978) Oxford

Biggs R.D., “An Archaic Sumerian Version of the Kesh Temple Hymn from Tell Abu Salabikh”, Zeitschrift Für Assyriologie, 61 (1971) 193–207