Empires of Mesopotamia:

Sumerian King List

Empires of Mesopotamia:

Sumerian King List

Discovery of the SKL

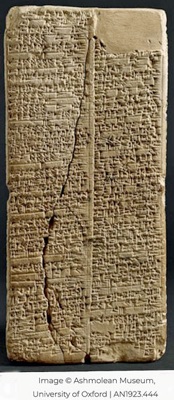

Old Babylonian Recension of the Sumerian King List (SKL) on the so-called Weld-Blundell (WB) Prism

Now in the Ashmolean Museum: image from the museum website

In a paper published in 1923, Stephen Langdon (referenced below) reported that:

“In the Cuneiform Collection founded and supported by Mr. H. Weld-Blundell for the Ashmolean Museum, I have found a large perforated prism which carries two columns of closely written text on each of its four faces. It purports to give the dynastic lists of the kings of Sumer and Akkad from the ante-diluvian period to the end of the reign of Sin-magir, the 13th king of [the Sumerian city of] Isin.”

The earlier provenance of the prism (illustrated above) is unknown. The terminus post quem of the Sumerian cuneiform text that it carries (labelled WB 444 by Langdon and transliterated as CDLI, P384786) is given by the reign of Sin-magir, the last-named king in the list, whose reign is usually given as ca. 1827 -1817 BC).

Fragments of similar texts had been known some years before Langdon’s ‘discovery’, but the connections between them only became apparent after his publication of the essentially complete WB 444. When Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below) published the first critical edition of the SKL in 1939, he was able to rely on WB 444 and 14 other (less complete) texts (which he listed at pp. 5-13). In 2004, Jean-Jacques Glassner (referenced below, at pp. 118-25) published an updated version of WB 444 (his ‘manuscript G’, see p. 117), which he entitled ‘Chronicle of the Single Monarchy’ (for reasons discussed below). Since then, the SKL corpus has expanded from 14 to 26 recensions, and these are the subject of a critical edition that Gösta Gabriel is about to publish: I would like to express my gratitude to Dr Gabriel for allowing me to read a pre-publication copy of this important (and much-needed) book.

As Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 235) pointed out:

✴24 of the 26 manuscripts in the modern corpus (including WB 444) date to the Old Babylonian period: and

✴there are two ‘chronological outliers’:

•the oldest known copy of the SKL was compiled in so-called Ur III period (ca. 2100–2000 BC), for which reason it is usually referred to as the USKL; and

•a single later manuscript probably dates to ca. 1600–1450 BC.

These texts are published as CDLI Literary 000371, with a composite at P479895.

Modern Corpus of the SKL Recensions

Table 1: Summary of the SKL corpus published by Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming, referenced below, referenced below)

Sallaberger and Schrakamp = Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at pp. 15-22)

Glassner = Jean-Jacques Glassner (referenced below, at pp. 117-8)

Jacobsen = Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below, at pp. 5-12)

(For convenience, I have numbered the 24 Old Babylonian recensions sequentially in the lefthand column)

The corpus analysed by Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming, referenced below) is summarised in Table 1 above. Unfortunately, there is, at present, no universally recognised method of labelling the individual texts:

✴Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming, referenced below) uses the labels in the second column, which reflect the locations of the respective find spots (where these are known); and

✴the following three columns give the alternative labels used in other important sources (see the references in the table notes).

As Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 235) pointed out:

✴24 of the 26 manuscripts in the corpus (which I have labelled as numbers 1-24 in the column at the extreme left) date (like WB 444 = number 24) to the Old Babylonian period (ca. 2000 = 1600 BC): and

✴there are two ‘chronological outliers’:

•the oldest known copy of the SKL was compiled in so-called Ur III period (ca. 2100–2000 BC), for which reason it is usually referred to as the USKL; and

•a single later manuscript probably dates to ca. 1600–1450 BC.

As noted above, we must await the publication of Gösta Gabriel’s forthcoming book for a complete edition of these 26 manuscripts. Meanwhile, convenient on-line sources for the Old Babylonian text include:

✴a composite transliteration and translation at CDLI (P479895); and

✴a composite translation divided by ‘city dynasties’ (see below) at ETCSL (translation: t.2.1.1).

In what follows, references to specific lines in these texts use the numbering system used by the CDLI.

Opening Lines of the USKL and the SKL Recensions

Although many of the surviving SKL recensions are fragmentary, we can be reasonably sure that they all began with essentially the same account of the descent from heaven of kingship (nam-lugal), an undefined privilege that the gods had conferred on a particular place (which, by implication, became the first kingdom). More specifically, each of the recensions that are reasonably complete in their opening sections can be assigned to one of two groups:

✴in some (picked out in pink in Table 1), the gods first bestowed kingship on Kish, where Gushur was king; and

✴in others (picked out in blue in Table 1) :

•the gods bestowed kingship on Eridu, where Alulim was king;

•he was the first of eight kings who ruled in succession in Eridu or one of four other cities before ‘the flood swept over’; and

•thereafter, when kingship returned from heaven, it was bestowed on Kish, where Gushur was king.

Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below, at p 63), who was unaware of the existence of the USKL (see below), concluded (on linguistic grounds) that:

“The role of the antediluvian section in the tradition of the [SKL] can no longer be doubted: it is a later addition.”

The case for this hypothesis was greatly strengthened by the publication of the USKL, so that (some 80 years later) Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p. 59) was able to restate it in even stronger terms:

“As is universally agreed by all the modern students of the SKL, the antediluvian section represents a later addition. This is confirmed by the fact that the [Antediluvian King List (AKL)] is not part of the [USKL]. ... The precise date at which this section was added to the SKL cannot be ascertained with certainty. However, the fact that [it] is closely connected with the ‘Deluge tradition’, whose earliest attestations seem to belong to the 20th century BC, indicates that this happened either in the Isin-Larsa period or sometime later in Old Babylonian times. ”

Thus, we can initially put the AKL preface to one side while we analyse the ‘SKL proper’ as it evolved over time.

Structure of the SKL

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 234) asserted that there is a stable core to the ‘story’ implicit in all of the known SKL recensions:

“It always begins with the divine transfer of kingship from heaven to earth into a first city. This city turns into the capital, its kings ruling the entire land. After a given time though, the gods turn away from this city, determining its fall. They transfer kingship into a new city which becomes the new hegemon. This pattern is repeated several times until the SKL ends in the present or in the recent past.”

I must insert an important caveat here: given the lacunose nature of the only known USKL ‘document’, we have no direct evidence that this hypothesis applies in the case of the pre-Sargonic ‘story’ told in the USKL.

Terminology: ‘City Dynasties’ or ‘Hegemonies’?

Modern historians mostly refer to the ruling cities of the kings named in the USKL (and in the SKL) as ‘dynasties’ (so that, for example, Ur-Namma and the other ‘Ur III’ kings are so-called because, at least in the SKL, they ruled at Ur when kingship was transferred there for the third time in its history). However, there is a problem with this usage of the word ‘dynasty’: as Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 13) pointed out, this differs from the general usage, in which the word refers to a group of successive rulers from the same bloodline (as in my reference to Sargon’s ‘dynastic successors’ above). Piotr Michalowski (referenced below, 2013, at p. 6448), addressed this problem by replacing the word ‘dynasty’ in the context of these king lists with ‘hegemony’: thus, for example, he described the SKL as:

“... a Sumerian school composition that records a sequence of hegemonic cities and kings from primordial times to the dominion of the Isin Dynasty in the 18th century BC.”

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at note 12, at p. 236) similarly argued that:

“Because the term ‘dynasty’ is commonly used to describe a set of rulers connected by family ties, ‘hegemony’ is better suited to denote the reign of a city in the [USKL and] SKL, whose rulers are not necessarily connected by a single bloodline.”

While this is an excellent point, it seems to me that the indiscriminate use of the word ‘hegemony’ raises its own problems, not least because it assumes that the SKL was predicated on the assumption that Gushur and all of the kings who followed him had exercised hegemony over essentially the same territory. In fact, as we shall see, nothing in the surviving text of the USKL suggests that this was necessarily the case. For this reason, in what follows, I retain the conventional practice of referring to the ruling cities of the USKL and the SKL as ‘dynasties’, but I use the terms ‘city dynasty’ and/or ‘familial dynasty’ when the meaning is otherwise unclear.

‘Transfer of Kingship’ Formulae

Given the relatively large number of surviving Old Babylonian recensions of the SKL, we can be certain that the transfer of kingship from one city dynasty to the next was articulated in these texts by the use of standard formulae. Thus, in the first of these transfers, we read that:

“Akka, son of Enmebaragesi, reigned [at Kish] for 625 years.

23 [‘Kish I’] kings [had] reigned [at Kish] for [just over 24, 510 years]

Kish was [then] struck with weapons [and] kingship was carried off to Eanna [=Uruk].

At Eanna, Mesh-kiag-gasher, son of Utu [= the sun god], was lord [and] king”, (SKL composite, lines 88-98).

This formulaic structure was used relentlessly throughout the text, so that the last transfer of kingship in the SKL was articulated as follows:

“Ibbi-Sin, son of Shu-Sin, reigned [at Ur] for 24 years.

[5 Ur III] kings [had] reigned [at Ur] for 108 years.

Ur was [then] struck with weapons [and] kingship was carried off to Isin.

At Isin, Ishbi-erra was king”, (SKL composite, lines 349-355).

The historical reality on this occasion was , of course, more complicated:

✴Ishbi-Erra had started his career as an officer under Ibbi-Sin, before rebelling, capturing Isin and founding his own ‘Isin dynasty’, from which point, he reigned as an independent king of Isin for at least 17 years,;

✴during this period, Ibbi-Sin’s ‘Ur III Empire’ continued to disintegrate, until he was finally defeated and imprisoned King Kindattu of Elam; and

✴Ishbi-erra (who had watched from the sidelines) subsequently ejected Kindattu from the devastated city of Ur, although he retained Isi as his capital.

In this context, Piotr Michalowski (referenced below, 1983, at p. 242) pointed to a striking passage in the Old Babylonian ‘Lament for Sumer and Ur’, a literary work from this period, which:

“... contains, in effect, a full articulation of Isin ideology.”

In this passage, the god Enlil explains to his ‘subordinate’, Nanna, the patron deity of Ur, why he (Nanna) should accept the fall of his city:

“The word of An and Enlil knows no overturning. Ur was indeed given kingship, but it was not given an eternal reign. From time immemorial, since kalam (the land) was founded, ... who has ever seen a reign of kingship that would take precedence for ever? The reign of [Ur’s] kingship had been long indeed, but it had to exhaust itself. O my Nanna, do not exert yourself in vain: abandon your city”, (‘Lament for Sumer and Ur’, lines 366-70).

As Michalowski (as above) pointed out, this lament and the SKL:

“... reflect the same ideology: Isin is in line to [take over] hegemony [over Sumer], and that is simply the way things are.”

It is often assumed that this formulaic approach was used to articulate the move from one city dynasty to another throughout the USKL. However. as noted above, there is no surviving direct evidence taht is was the case in the pre-Sargonic period. However, the three surviving ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae survive in the later part of the text:

✴when Kuda(who, in the SKL, was the 3rd king of the Uruk IV city dynasty) had reigned for 5 years:

“Uruk was struck with weapons [and] kingship was carried to the ummanum [= the Gutian ‘barbarians’]”, (reverse, col. 2, lines 13’-16’);

✴after the rule of a number of Gutians, and when the last of them, Tirigan, had reigned for only 40 days:

“The weapon was struck near (?) Adab [and] the kingship was carried to Uruk, [where] Utu-hegal was king”, (reverse col. 3, lines 10’-14’; see also Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 243 and notes 35-6); and

✴after Utu-hegal had reigned at Uruk for 7 years:

“Uruk was struck with weapons [and] kingship was carried to Ur, [where] Ur-Namma reigned for 18 years”, (reverse, col. 3, lines 17’-20’).

As discussed below, there no reason to doubt the formulaic transfer of kingship from Kuda at Uruk to the Gutians reflected actual events as they were understood in Ur III times. The descriptions of the other two transfers of kingship are clearly historically accurate (albeit that the second of these is extremely short on detail):

✴Utu-hegal commemorated his victory over Tirigan near Adab in a surviving royal inscription (RIME 2:13:6:4; CDLI. P433096); and

✴Utu-hegal’s victory, his later demise (in whatever circumstances), and Ur-Namma’s subsequent rise to power had occurred within living memory.

USKL Recension

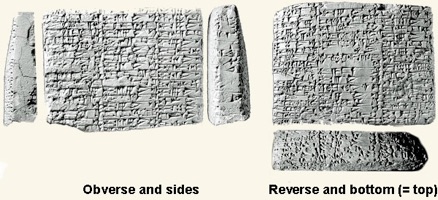

Surviving part of the tablet containing the Ur III recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL):

the tablet is in a private collection and the image adapted from CDLI: P283804

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003), to whom we owe the publication of the only surviving USKL tablet, provided a transliteration of the surviving text, together with an important initial commentary. A transliteration and photographs are also available on line at CDLI: P283804. In what follows, references to specific lines in these texts adopt the numbering system used by the CDLI.

The surviving USKL text is arranged in three columns on each side of this tablet fragment (with that on the reverse sometimes continuing onto the bottom). Since the opening and closing lines of the original text survive, we know that:

✴it begins (at obverse, col. 1, line 1) with the claim that:

“After kingship was brought down from heaven, Kish was king. In Kish, Gushur ruled for 2,160 years”, (see the translations by Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, at p. 231 and Gösta Gabriel, 2023, referenced below, at p. 247); and

✴it ends with:

•the name of Ur-Namma, the founder of the ‘Ur III’ dynasty, who had reigned for 18 years (reverse, col. 3, lines 21-2); and

•the scribe’s dedication of his handiwork to Shulgi, his king (see below).

Shulgi was the late (and presumably lamented) Ur-Namma’s son and successor.

The scribe’s dedication reads:

“... [to the divine] Shulgi, my king: may he live until distant days (see Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 269).

Steinkeller argued that, since Shulgi was given a divine determinative here, this text must have been compiled at some time between:

✴his 20th regnal year (the approximate date of his deification); and

✴his 48th regnal year (the approximate date of his death).

In other words, the USKL was compiled in ca. 2074-2047 BC.

Kishite Kings in the USKL

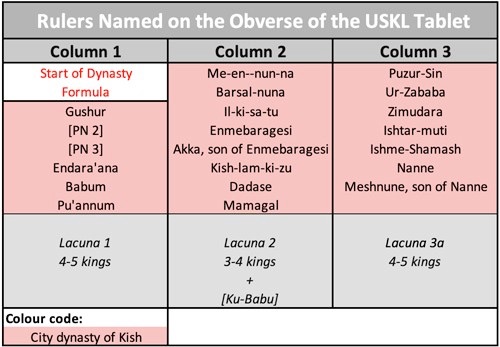

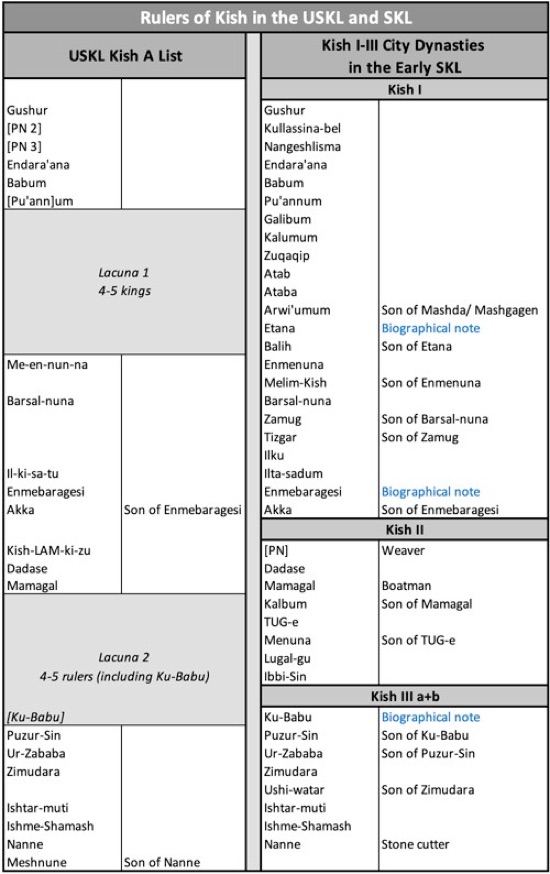

Table 2

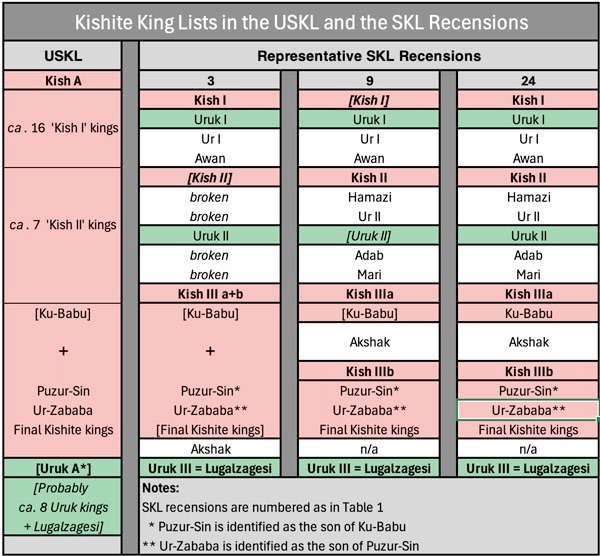

As indicated in Table 2 above, the surviving text on the obverse of the USKL tablet includes the opening declaration quoted above, followed by the names of 21 rulers of Kish (each of which is followed by the corresponding reign length). Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 237 and note 17) labelled this as the ‘Kish A’ part of the USKL list.

Table 3: Comparison of the Kishite king lists in the USKL and the later SKL recensions

Names based principally on Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming, referenced below)

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) recognised that the USKL list of Kishite kings had formed the basis of the list in the later SKL recensions, albeit that it had been:

✴extended to include 39 names;

✴elaborated in some cases by the introduction of short biographical notes; and

✴split into 3 or 4 segments by the introduction of intervening ‘city dynasties’.

It thus became clear that, in the USKL:

✴Gusher must have been followed by about 30 more Kishite kings (although only 21 names, including that of Gusher, survive); and

✴these Kishite kings would have represented about 40% of all the kings named between Gusher and Ur-Namma.

Lacunae 3a and 3b of the USKL

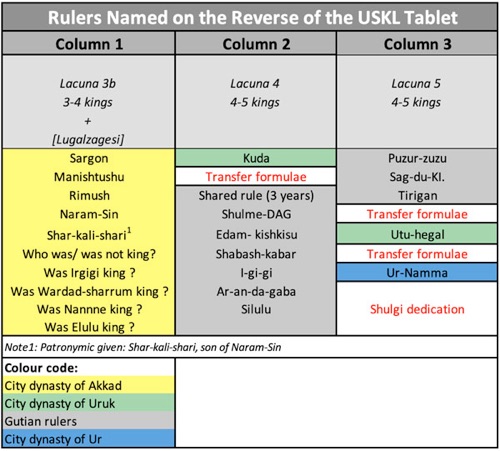

Table 4: Reverse of the USKL

The text in column 3 on the obverse of the surviving USKL tablet :

✴was broken immediately after the record of the Kishite king Meshnune, son of Nanne (see Table 2); and

✴began again about half way down the first column on the reverse, with the information that Sargon ruled in Akkad for 40 years (see Table 4).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) observed that the completion of the intervening lacunae (labelled Lacuna 3a and Lacuna 3b in Tables 2 and 4 above) is extremely problematic. However, as he pointed out, we know that the last of these rulers was almost certainly Lugal-zagesi of Uruk, whom Sargon famously defeated, thereby becoming the king of both Akkad and Sumer.

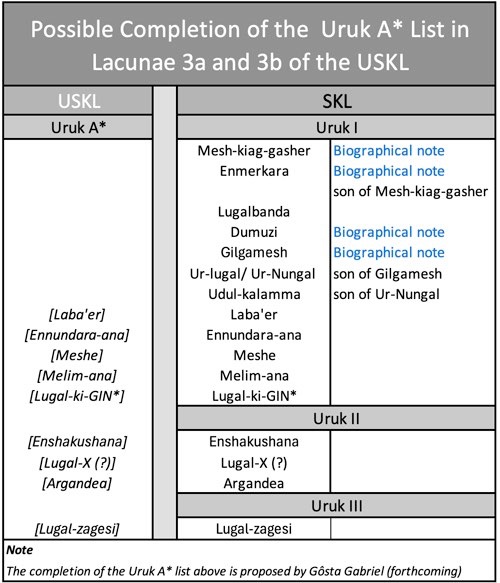

Table 5: Completion of the USKL Uruk A* list, as proposed by Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming, referenced below)

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at pp. 274-5) considered the possibility that all of the kings in this long lacuna were kings of Uruk (his ‘option a’). However, he had two problems with this hypothesis:

✴he estimated that there would not have been room for all of the 15 other kings of Uruk who were named before Lugal-zagesi in the SKL (12 in the Uruk I dynasty and 3 in the Uruk II dynasty - see Table 5); and

✴the inclusion of the earliest of them (all of whom were given ‘superhuman’ reigns in the SKL, indicating that they belonged to the mythical past) would have violated:

“... the diachronic principle to which the USKL otherwise religiously subscribes”.

In other words, since he reasonably assumed that Meshnune was the last Kish A king in the USKL, his name must have been followed by ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae and then the name of a contemporary ruler from another city dynasty.

However, he also rejected other options based on the SKL (his options b and c), and observed that:

“... there seems to be no possibility of resolving these questions at this time.”

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, note 16, at p. 237) nevertheless argued that:

“Uruk is the most likely candidate for [reconstructing this lacuna, which he labelled the ‘Uruk A*’ list]. This [putative city dynasty] ... probably did not include its first five [Uruk I kings in the SKL]: Mesh-kiag/kin-gasher; Enmerkara; Lugalbanda; Dumuzi; and Gilgamesh.”

In Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming, referenced below), he also argued for the omission of the next two Uruk I kings, Ur-lugal and Udul-kalama, who were both descendants of Gilgamesh. In this scenario (which is illustrated in Table 5), the long lacuna therefore contained:

✴the last four SKL Uruk I kings;

✴the three SKL Uruk II kings; and

✴Lugal-zagesi (the sole SKL Uruk III king);

whom Gabriel assumed would be easily accommodated (along with two sets of ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae) in the lacunae between Meshnune and Sargon. Since both Meshnune of Kish and Laba’er of Uruk are otherwise unknown, it is possible that, in Ur III times, they were regarded as contemporaries. In other words, if it is assumed that the USKL did indeed ‘religiously subscribe’ to the diachronic principle, then Gösta Gabriel’s Uruk A* list (with appropriate transfer formulae before and after it) is one possibility for the completion of this part of the list.

USKL from Sargon of Akkad to Kuda of Uruk

Table 6: Completion of the USKL text in Lacuna 4

As set out in Table 6, the surviving USKL text:

✴is broken after the so-called ‘period of confusion’, in which it seems that. nobody could be sure about who was the king of Akkad; and

✴resumes with Kuda, who is the third of the Uruk IV kings in the SKL.

We might therefore reasonably assume that, on the basis of the SKL, Lacuna 4 in the USKL can be completed with:

✴Dudu and Shu-Turul, both of whom are known from royal inscriptions (see Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 1993, at pp. 210-7);

✴transfer formulae from Shu-Turl to Ur Nigin at Ur; and

✴Ur Nigin and Ur-gigir, both of whom are also known from royal inscriptions (see Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993, at pp. 274-7)

If the reconstruction of Lacuna 4 set out above is correct, then, at least in this text:

✴Ur-nigin of Uruk apparently threw off the hegemony of Shu-Durul of Akkad; and

✴Uruk then remained independent until Kuda was defeated by the Gutians.

The Gutians

We now come to the first surviving ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae in the surviving text of the USKL (as discussed above): when Kuda had reigned at Ur for 5 years:

“Uruk was struck with weapons.

Its kingship was carried off to the ummanum (the Old Akkadian word for horde or army).

The ummanum had no king: they ruled themselves (shared command ??) for three years”, (reverse, col. 2, lines 13’-18’).

In the SKL (at lines 307-8), the kingship was carried to ugnim gu-tu-um (where ugnim is the Sumerian equivalent of ummanum and gu-tu-um identifies the army in question as that of ‘Gutium’).

In the USKL, these ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae were followed by:

✴6 Gutian kings in the rest of column 2;

✴about 5 (presumably Gutian) kings in what is now Lacuna 5; and

✴3 Gutian kings in the rest of column 3, the last of whom was Tirigan (who ruled for only 40 days).

Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, referenced below, Table 7, at p. 20) compared this list with those of all the other known SKL recensions:

✴in the most complete of these (WB 444), 21 Gutian kings ruled for 91 years; and

✴in another four recensions thin which the ‘summary of hegemony’ formula survives, 21-23 Gutian kings ruled for 99-125 years.

In other words, it seems that the number of Gutian kings was increased from about 14 in the USKL to about 21 in the SKL. Nevertheless, the Gutian list was the second-longest in the USKL, accounting for about 20% of all the kings named between Gusher and Ur-Namma.

Utu-hegal of Uruk

The USKL list of Gutians is followed by the second ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae in the surviving text : after the Gutian King Tirigan had ruled for only 40 days:

“The weapon was struck near (?) Adab.

The kingship was carried to Uruk.

In Uruk, Utu-hegal was king”

This translation is proposed by Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 243 and notes 35-6): he noted that these ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae differ in a semantic sense from the formulation in the SKL (at SKL 332-5):

“The Gutian army (ugnim gu-tu-um) was struck with weapons.

The kingship was carried to Uruk.

In Uruk, Utu-hegal was king.”

His point was that:

“In the case of the Gutians’ defeat [in the USKL], the locative (or directive) case does not mark the object hit by the weapon, but [rather marks] the location at which the action took place. Since [a surviving royal inscription - see below - places] Utu-hegal’s final victory over the Gutians at a place close to Adab, [this particular] ‘collapse formula’ ... can be translated as:

‘The weapon was struck near (?) Adab’.”

As he pointed out (at note 36), his alternative translation removes the need to assume (with Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 276 and p. 281) that there must have been a set of ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae from the ummanum to Adab in Lacuna 5). Note. however, that some scholars follow Steinkeller in this respect(see, for example, Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, referenced below, Table 7, at p. 20).

As noted above, we have epigraphic evidence for Utu-hegal’s victory over Tirigan. This is in the form of three Old Babylonian copies of the inscription from the ‘victory’ monument of Utu-hegal. (A composite of these three Old Babylonian texts is available on-line as RIME 2:13:6:4; CDLI. P433096). Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p. 11) cautioned that the late date of this evidence:

“... opens up a possibility that, despite its seemingly genuine late 3rd millennium characteristics, as pertains to its orthography and grammar, the Utu-hegal inscription may actually be a literary text that was composed subsequent to Utu-hegal’s own time.”

However, as Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, note 33, at p. 243) observed:

“... there is a close link between:

✴the events reported in [the surviving Old Babylonian copies of] Utu-hegal’s inscription; and

✴specific features of the USKL;

which suggests that there was some kind of connection between the two texts. This does not prove the historical truth of the narrated events, but it does indicate that Utu-hegal’s inscription existed in one form or another [by the time that] the USKL was compiled.”

This inscription began by recording that Enlil had commanded the obliteration the name of:

“... Gutium, the fanged snake of the mountain ranges, a people who acted violently against the gods [by, inter alia] ... taking the kingship of Sumer (nam-lugal ki-en-gi-ra) away to the mountains ...”, (RIME 2:13:6:4; CDLI. P433096, lines 1-6).

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 283) observed, this must refer to the change of control at Uruk that, in the USKL, had happened in the reign of king Kuda. The inscription then recorded that Enlil:

“... commissioned Utu-hegal, the mighty man, king of Uruk, king of the four quarters, ... to destroy [the Gutian] name. ... Enlil commanded [Utu-hegal] to return the kingship of Sumer to its own control”, (lines 15-31).

Interestingly, the inscription also recorded that Utu-hegal’s victory over Tirigan’s army took place near Adab (see line 90). After his defeat in this battle, Tirigan escaped to Dabrum, where he was captured, and:

“... the kingship of Sumer returned to its own control”, (line 128).

Ur-Namma

One of the most surprising things about the USKL is the laconic nature of its record of Ur-Namma: after Utu-hegal had reigned at Uruk for 7 years:

“Uruk was struck with weapons [and] kingship was carried to Ur, [where] Ur-Namma reigned for 18 years”, (reverse, col. 3, lines 17’-20’).

As we have seen, this formulation (with only a single addition) was used for all of the transfers of kingship in the SKL. Thus we read therein that,when Ur-Namma’s Ur III dynasty had run its course after 5 Ur IIIkings had reigned for 108 years:

“Ur was truck with weapons [and] kingship was carried off to Isin, [where] Ishbi-erra was king”, (SKL composite, lines 353-355).

Interestingly, Ur-Namma’s route to the kingship was very similar to that of Ishbi-Erra:

✴he had also been a military governor, in his case at Ur, which acknowledged Utu-hegal as its hegemon (see RIME 2.13.6.2001, P462114); and

✴he apparently went on to rebel against Utu-hegal, since he was surely the ‘man of Ur’ who laid claim to land that had long belonged to Lagash, which still acknowledged Utu-hegal’s hegemony (see, for example, RIME 2.13.6.1, P462109).

The likelihood is that despite Utu-hegal’s claim to have destroyed the Gutians, they were still able to undermine his hold on the kingship of Uruk and its vassal cities. In circumstances such as these, we cannot assume that Ur-Namma’s putative rebellion was the direct cause of his fall (just as Ishbi-erra’s rebellion was not the direct cause of the fall of Ibbi-Sin). Hence the similarity on their respective transfer formulae: the city dynasty of Uruk had run out of steam and Ur is now in line to assume the hegemony over Sumer, which (following Michalowski, above) was simply the way things were.

From USKL to SKL

Pre-Sargonic Period

Table 7

The first column of Table 7 contains a summary of the structure of the USKL between Gushur at Kish and Lugal-zagesi at Uruk, as discussed above. This is the starting point for the other columns, which reflect the corresponding structure of the SKL, as represented by three reasonably complete examples:

✴recension 3, which can be placed securely in the ‘early’ group that begin with Gushur;

✴recension 9, which is broken at the start, but which is included here because it is the only recension other than recension 24 that contains a reasonably complete list of the Kish II kings; and

✴recension 24, because it:

•remains the most complete of the known Old Babylonian recensions; and

•can be placed securely in the ‘late’ group of recensions that begin with the AKL preface.

The most striking thing about this comparison is that a major structural change took place between the USKL and the early SKL recensions:

✴the single ‘Kish A’ list of the USKL was split into four distinct ‘city dynasties’ (labelled Kish I, Kish II, Kish IIIa and Kish IIIb (see below) by a number of ‘intervening’ dynasties;

✴the putative Uruk A* list of the USKL was apparently split into three (Uruk I, Uruk II and Uruk III) and included among these ‘intervening dynasties’; and

✴other ‘new’ ‘intervening dynasties’ (Ur I and II, Awan, Hamazi, Adab, Mari and Akshak) were added to the list.

As we shall see, in all of the post-USKL recensions that are unbroken at the bottom, the last named king ruled at Isin. Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p.21) therefore argued that:

“It was [in the Isin period] that the SKL acquired its final form.”

This basic stability in the dynastic structure of the SKL recensions is clear from Table 7, albeit that, in the Isin period, significant change were made to the part of the list between Ku-Babu of Kish and Lugal-zagesi of Uruk.

Ku-Babu, the only queen recorded in any known recension of the SKL, was probably also recorded in the USKL immediately before Puzur-Sin and Ur-Zababa (as suggested in Table 7). Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below, at p. 53) observed that, in the SKL:

✴she sometimes (as in recension 3 in Table 7) similarly appears at the head of a single city dynasty (his Kish III), immediately before:

•Puzur-Sin and Ur-Zababa, who are now described as her son and grandson respectively; and

•the remaining Kishite kings; and

✴on other occasions (as in recensions 9 and 24 in Table 7), she appears alone in a single ‘city dynasty’ (still his Kish III), separated from her son and grandson and the other remaining Kishite kings (his Kish IV).

Jacobsen argued that Ku-Babu had originally had her own ‘city dynasty’, and that Akshak had subsequently been moved down the list so that she then joined the city dynasty of her descendants. However, Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 237 and note 17), who had the benefit of a larger number of exemplars (including the USKL), realised that the reverse must have been the case. He therefore suggested that:

“[Jacobsen’s] ‘Kish IV’ should rather be called Kish IIIb, since it was created through a later separation of Ku-Babu from her successors. The earliest [SKL recensions] still record a single Kish III [city dynasty], from Ku-Babu through to Nanne, [the last-named Kishite king in the SKL].

In other words:

✴in the early SKL recensions, Ku-Babu was immediately followed by Puzur-Sin, Ur-Zababa and the other remaining Kishite kings (as she had been in the USKL, albeit that she is now explicitly identified as the mother of Puzur-Sin and the grandmother Ur-Zababa); while

✴subsequently (and for now-unknown reasons), Akshak was moved up the list to separate Ku-Babu (now in her own Kish IIIa dynasty) from her direct descendants and the other remaining Kishite kings (now in a separate Kish IIIb city dynasty).

Implications for the Relative Chronology of the SKL Recensions

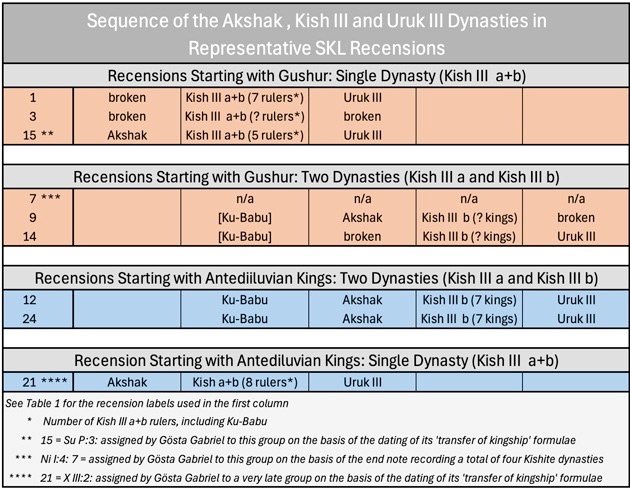

Table 8: Chronological groups within the SKL corpus

Thus, it seems that two significant changes were made to the structure of the earliest SKL recensions:

✴the AKL preface was added (as discussed in an earlier section); and

✴the original single Kish III city dynasty was split into two (labelled Kish IIIa and Kish IIIb)

Table 8 summarises the results of the detailed analysis of all 24 of the known SKL recensions from Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming, referenced below). Importantly, he established that the addition of the AKL preface was the later of these two developments, which allowed him to refine his model for their relative chronology, in which almost all of the 24 known recensions could be assigned to one of three main chronological groups (with recension 21 as a structural outlier).

Implications for the Historical Relevance of the SKL Recension

As is clear from Table 7:

✴the USKL started with a continuous list of Kishite kings between Gushur and Meshnune; and

✴for whatever reason, the compilers of all of the known SKL recensions introduced 9 ‘intervening dynasties’ into this list.

In the earliest of these later recensions. the sequence was:

Kish I; Uruk I; Ur I; Awan; Kish II; Hamazi; Ur II; Uruk II; Adab; Mari; Akshak; Kish III (a+b);

and there were only minor variations in this sequence thereafter. A (possibly unintended) consequence of this structural change was a fundamental change in the way in which the history of this period was portrayed:

✴in the USKL, a succession of presumably local kings had reigned at Kish (however defined) from time immemorial until at least the reign of Meshnune, son of Nanne; while

✴in the SKL, the kingship over a wide swathe of Mesopotamia (Glassner’s ‘single monarchy’ - see above) had passed from Kish to Uruk, from Uruk to Ur , from Ur to Awan, from Awan back to Kish and so on during this period.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced bellow, 2017, at p. 194) expressed this development much more elegantly:

“As far as one can tell, the most significant difference between the [USKL] and its later version [= the SKL], is that the USKL organises the events in an unmistakably linear fashion: after the kingship descended from heaven in time immemorial, it remained for thousands and thousands of years in Kish, down to Sargon’s very day. ... Unlike in the [SKL], there is no suggestion in it that, in [the pre-Sargonic period], kingship wandered cyclically from place to place.”

The SKL’s ‘cyclical’ order of events is clearly unhistorical: although our understanding of the political dynamics of this period inevitably leaves much to be desired, we can be certain that it was not characterised by a single Mesopotamian monarchy that wandered in a cyclical fashion from one capital to another.

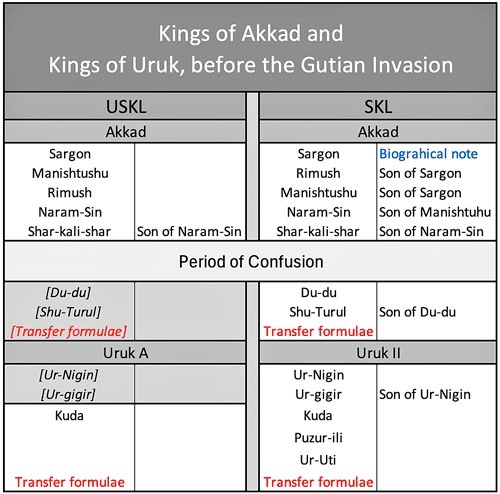

From Lugal-zagesi to Ur-Namma

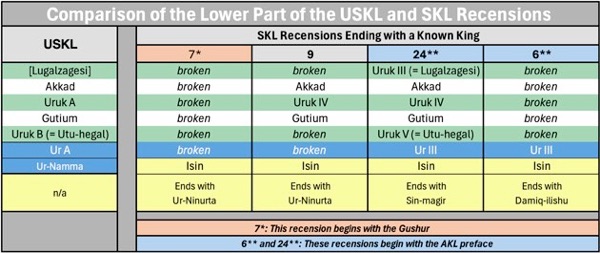

Table 9

The obvious point to make in the light of Table 9 is that the structure of the SKL between Lugal-zagesi and Ur-Namma is essentially the same as that of the USKL. Thereafter, the compilers of the later recensions extended the USKL list by adding:

✴Shulgi and three more kings of Ur; and

✴formulae for the transfer of kingship from Ur to Isin, followed by records for:

•King Ishbi-Erra of Isin (who actually recaptured Ur after its fall to King Kindattu of Elam, an event that is unacknowledged in the SKL); and

•his successors at Isin.

The four SKL recensions summarised in Table 9 are the only ones that still preserve the name of the last king that they originally recorded:

✴Two of them (numbers 7 and 9) ended with Ur-Ninurta, the 6th of the 15 Isin kings, who is almost always described in the SKL as the son of the weather god, Ishkur. In these two recensions, his name is followed by a dedication:

“Ur-Ninurta, the son of Ishkur: may he have years of abundance, a good reign and a sweet life”, (see line 365 in this composite translation by ETCSL).

This suggests that these recensions were both compiled while Ur-Ninurta was still alive (albeit that the surviving ‘manuscripts‘ are later copies).

✴Recension 24 (= WB 444) certainly ended with Sin-magir, suggesting that it was compiled in either Sin-magir’s own reign or in that of his son and successor, Damiq-ilishu (the last of the Isin kings).

✴Recension 6 records the name of Damiq-ilishu himself, which suggests that it was originally compiled during or shortly after his reign.

Unsurprisingly, the last two of these recensions began with the AKL preface. However, the situation with the first two recensions is more interesting: as noted in Table 3, they were both compiled in the second chronological phase:

✴after the splitting of the Kish III dynasties, so that Ku-Babu was separated from her son and grandson by the ‘intervening’ city dynasty of Akshak; but

✴before the addition of the AKL preface..

Thus the splitting of the Kish III dynasty took place either before or during Ur-Ninurta’s reign. (Since Ur-Ninurta is the first of the Isin kings who is not described in the SKL as the son of the king who preceded him, it seems to me that he is much more likely than his predecessors to have made this change.)

From USKL to SKL: Conclusions

The USKL had a relatively simple dynastic structure, which Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 237 and notes 16 and 17) summarised as:

“Kish A–[Uruk A*] – Akkad– Uruk A – Gutium – Uruk B – Ur A”

However, at some time after the reign of Shulgi at Ur;

✴the long ‘Kish A’ in the USKL was cut into three shorter lists;

✴the much shorter ‘Uruk A*’ list was first significantly extended and then cut up into three parts;

✴these Uruk I, Uruk II and Uruk III lists, along with other new ‘city dynasty’ lists (Ur I and II, Awan, Hamazi, Adab, Mari and Akshak) were introduced as ‘intervening dynasties’ separating Kish I, Kish II and Kish III from each other; and

✴in or after the reign of Ur-Ninurta at Isin, Akshak was moved up the list to separate Ku-Babu from her direct descendants and the other subsequent kings of Kish (creating the Kish IIIa and Kish IIIb city dynasties).

Precursors of the USKL

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at pp. 281-2) argued that, although the USKL can be securely dated to the latter part of Shulgi’s reign, this does not necessarily mean that this date should also be assigned to the compilation of the list itself, not least because;

“... it is inconceivable that Shulgi would have had had any part in a project that assigns much of the past glory to Kish, ... This leaves us with only one possible agency [for the Kish A list]: Sargon [of Akkad and his successors, who would] have had an obvious interest in promoting the idea that Kish remained the seat of kingship from time immemorial down to Sargon’s own day. In such a scheme of history, Akkad became a natural heir and successor to Kish, with a brief period of Urukean domination from Enshakushana to Lugal-zagesi representing but an aberration from the normal state of affairs.”

In a later paper, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p. 40) returned to this important hypothesis, arguing that the precursor of the USKL:

“... was probably written down in Sargonic times, with an express objective of demonstrating that, save for a brief interlude involving Lugal-zagesi and perhaps some other kings of Uruk, the Sargonic dynasty was a continuation of the kingdom of Kish.”

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023 at p. 244) argued that the Kish A list must have been based on the Kishites’ own historiographical tradition, in which case:

“... the first [precursor] of what would become the [USKL] was most likely written in Kish before ca. 2350 BC.”

In this scenario, Sargon or one of his successors sought to establish the legitimacy of the Akkadian rule of Kish by (inter alia) adding the names of the successive kings of his own dynasty to the ‘official’ list of kings of Kish, presumably with a short narrative that set out the circumstances in which this kingship had passed to Sargon (who was already the king of Akkad). Unfortunately, the USKL is of no help in establishing the likely content of this putative narrative, since the ca. 30 lines of text between the records of Meshnune (the last name in the surviving Kishite list) and Sargon of Akkad have been lost. However:

✴we know from their royal titles that the early Akkadian kings derived considerable advantage by associating themselves with kingship of Kish (despite this was but one of the many former city-states that they controlled; and

✴(pace Piotr Steinkeller, above) Shulgi presumably retained (and probably extended and elaborated) this list precisely because he wished to portray his father, Ur-Namma (and thus also himself) as the legitimate heir of both Sargon and the long line of kings of Kish who had preceded him.

In short, there was clearly something very special about the kingship of Kish.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 283) suggested that Utu-hegal had been responsible for the addition of:

✴the last rulers of Akkad;

✴the ‘undistinguished princelings’ of the Uruk IV dynasty; and

✴the Gutians;

to the putative Sargon precursor of the USKL. He observed that:

“In my opinion, [the first passage from Utu-hegal’s victory inscription quoted above] proves conclusively that the tradition of the [Uruk IV dynasty] as an earlier possessor of kingship, and therefore Akkad’s direct heir, had been alive, whether in written or oral form, during Utu-hegal’s time. By this logic:

✴the Gutian interlude constituted an unlawful appropriation by a foreign party; [and]

✴by defeating Tirigan, Utu-hegal simply restored to Uruk what had been [rightfully] hers.”

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 244) similarly concluded that:

“... the parallels between [Utu-hegal’s victory] inscription and USKL indicate that, [in the USKL], the sequence:

✴Uruk A [= Uruk IV];

✴Gutium;

✴Uruk B [= Utu-hegal];

can be ascribed with reasonable certainty to Utu-hegal. He altered pre-existing concepts of the past to bolster his claim to power in [Mesopotamia], codifying these into [an early] recension of the SKL that has not survived, but whose structure was integrated into the USKL.”

Structure of the USKL Text for the Pre-Sargonic Kingship

As noted above, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at pp. 275) observed, the biggest barrier to out understanding of the structure of the USKL is presented by the uncertainty surrounding the identification of the kings who would have been named between Meshnune of Kish and Sargon of Akkad. He assumed that the last four names in this list would have been the three Uruk II kings from the SKL, followed by the Uruk III king Lugal-zagesi, but argued that:

“... the real crux is what was listed before them.”

Steinkeller saw no obvious solution to this problem, but Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming, referenced below) argues that the most likely candidates are the last 5 of the 12 Uruk I kings (see Table 5 above.

Interestingly, both Steinkeller and Gabriel assumed that all of the names in this part of the USKL text had originated in the putative Sargonic recension. However, we have no direct evidence that this was the case. Furthermore, there is some evidence to suggest that at least one of the early Uruk I kings, Gilgamesh, would have been named in Utu-hegal’s putative recension: in his victory inscription (above), Utu-hegal claimed that:

“The god Gilgamesh, son of the goddess Ninsun, has assigned [Dumuzi] to me as mashkim) bailiff/ deputy )”, (RIME 2:13:6:4; CDLI. P433096, lines 61-3).

Dina Katz (referenced below, at p. 31) reasonably argued that:

“The appearance of Gilgamesh in this context indicates not only that Utu-hegal knew the tale of Gilgamesh' war of liberation [of Uruk from the hegemony of Kish], but also that his achievement was an inspiration for Utu-hegal in his own war [against the Gutians]”.

It is thus quite likely that the putative ‘Utu-hegal recension’ of the USKL portrayed Utu-hegal as the ‘new Gilgamesh’.

Further support for this hypothesis can be found in the opening lines of the literary source known as the ‘Curse of Akkad’:

“After Enlil’s frown had:

✴slain Kish, as if it were the Bull of Heaven; [and]

✴slaughtered the house of the land of Uruk in the dust, as if it were a mighty bull;

Enlil gave the lordship and kingship, from the south as far as the highlands, to Sargon, king Akkad.”, (‘Curse of Akkad’, lines 1-6).

In other words, in this account, Sargon became lord and king of Mesopotamia after Enlil had destroyed Kish and then Uruk. It is therefore possible that:

✴the putative Sargonic king list discussed above contained a single list of the kings who had allegedly reigned in direct succession at Kish from time immemorial until the time of Sargon and his ‘Akkadian’ successors; and

✴the putative ‘Utu-hegal’ recension recorded:

•Gilgamesh’s liberation of Uruk from the hegemony of Kish, which lasted until the reign of Lugag-zagesi;

•Ur-nigin’s liberation of Uruk from the hegemony of Akkad, which lasted until the rein of Kuda; and

•Utu-hegal’s liberation of Uruk from the hegemony of Gutium, at which point, as he recorded in his victory inscription, he:

“... brought back the kingship of Kiengi [to Uruk]”, (RIME 2:13:6:4; CDLI P433096, line 128).

If this hypothesis is accepted, then Shulgi’s scribe did not simply reproduce the Sargonic and the Urukean recensions in succession and then add the name of Ur-Namma. Nor did he ‘religiously subscribe’ to the diachronic principle (as Piotr Steinkeller assumed).

In this context, it is important to note that Shulgi would have been familiar with the literary work now known as the ‘Curse of Akkad’: as Jerrold Cooper (referenced below, at p. 41) pointed out, the earliest surviving fragments of this text (all of which come from Nippur) date to the Ur III period, and, although they only preserve 35 lines or parts of lines of this version:

“... this is enough to indicate that we are dealing with [an Ur III text that was] very close to that of the [much more complete later Old Babylonian manuscripts] ...”

Thus, the sequence Kish - Uruk - Akkad would have been an obvious template for the pre-Sargonic part of the USKL. Shulgi would also have been very familiar with the way in which Utu-hegal had justified his right to rule, and he would naturally have sought to incorporate this version of history in the USKL, thereby portraying Ur-Namma as the natural heir of the Uruk kings. Perhaps even more importantly, he would surely have had the example of Gilgamesh very much in mind. The tale of Gilgamesh' liberation from the hegemony of Kish, was definitely known at the court of Shulgi, as evidenced (for example) in:

✴a praise poem of Shulgi known as ‘Hymn O’ (lines 56-60, see the translation by Ludek Vacin, referenced below, at p. 224), in which Gilgamesh liberates Uruk from the hegemony of King Enmebaragesi of Kish; and

✴the Sumerian poem known as ‘Gilgamesh and Akka’ (one of the five known Sumerian poems about the hero Gilgamesh) in which his adversary is now Enmebaragesi’s son and successor, Akka.

Furthermore, as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p. 141) observed:

“... the Ur III kings [themselves] traced their descent primarily to the mythical, semi-divine kings of Uruk, such as Lugalbanda and Gilgamesh. Although [this development] may have already begun under Ur-Namma, it was only during the reign of Shulgi that [it] acquired its full formulation.”

It seems to me that Gilgamesh, at least, must have featured in the USKL, which suggests that the pre-Sargonic text of the USKL was much more than a simple derivative of two earlier recensions (just as the pre-Sargonic record in the SKL was much more than a simple derivative of this part of the USKL).

I will attempt to develop this suggested scenario for the evolution of the USKL throughout the following discussion of the history of early kingship in Mesopotamia, particularly at Kish, Akkad, Uruk but also at Lagash and Umma, before looking it again ‘in the round’ in my discussion of the reign of Shulgi.

References

Gabriel G. I., "Die ‚Sumerische Königsliste’ als Werk der Geschichte: Kritische Editionsowie text-, stoff- und konzepthistorische Analyse”, (forthcoming): I would like to express my gratitude to Dr Gabriel for allowing me to read a pre-publication copy of this much-needed book

Gabriel, G. I.,"The ‘Prehistory’ of the Sumerian King List and Its Narrative Residue", in:

Konstantopoulos G. and Helle S., “The Shape of Stories”, (2023) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 234-57

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2017) Boston and Berlin

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 1-130

Michalowski P., “Sumerian King List”, in:

Bagnal R. S. et al. (editors), “The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, First Edition”, (2013), at pp. 6448-9

Vacin L., “Šulgi of Ur: Life, Deeds, Ideology and Legacy of a Mesopotamian Ruler As Reflected Primarily in Literary Texts”, (2011), thesis of the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London)

Marchesi G., “The Sumerian King List and the Early History of Mesopotamia”, in:

Biga M. G. and Liverani M. (editors.), “Ana Turri Gimilli: Studi Dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer da Amici e Allievi”, (2010) Rome, at pp 231-48

Glassner J.-J., “Mesopotamian Chronicles”, (2004) Atlanta GA

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-292

Katz D., “Gilgamesh and Akka”, (1993) Groningen

Cooper J., “Curse of Agade’, (1983) Baltimore MA and London

Michalowski P., “History as Charter Some Observations on the Sumerian King List”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 103:1 (1983) 237=48

Jacobsen T., “The Sumerian King List”, (1939) Chicago IL

Langdon S. H., “The H. Weld-Blundell Collection in the Ashmolean Museum: Vol. II: Historical Inscriptions, Containing Principally the Chronological Prism (WB. 444)”, (1923) London