Persian Empire

Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great, 559 - 530 BC)

Main page: Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great, 559 - 530 BC)

Topic: Royal Titles of Cyrus the Great

Persian Empire

Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great, 559 - 530 BC)

Main page: Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great, 559 - 530 BC)

Topic: Royal Titles of Cyrus the Great

Royal Titles of Cyrus the Great

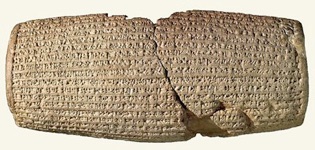

Cyrus Cylinder

Inscribed clay cylinder known as the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ from the foundations of the wall of Babylon

Image from the site of the British Museum, where the tablet is now housed (BM 90920)

The only known proclamation in Cyrus’ own ‘voice’ was inscribed in Babylonian (Akkadian) cuneiform on a clay cylinder (illustrated above) from Babylon that related to his capture of the city in 539 BC. In the inscription, he described how Nabonidus, the erstwhile king of Babylon, had offended Marduk the most important of the Babylonian gods, with the result that Marduk had:

“... inspected (and) examined all of the lands [of the world], everyone of them, and constantly sought out a righteous king, the desire of his heart. He took Cyrus (Kurash), lugal uru Anshan (king of the city of Anshan) by the hand, called (him) by his name (and) proclaimed him to be the ruler of the entirety of everything”, (RIMB, Cyrus II, 1: i, 11-12).

Cyrus also introduced himself to his new Babylonian subjects as:

“... king of the world, great king, strong king, king of Babylon, king of the land of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four quarters (of the world), the:

✴son of Cambyses (Kambuzia), great king, king of Anshan;

✴grandson of Cyrus (I), great king, kin[g of] Anshan; and

✴descendant or great grandson (liblibbu) of Teispes (Shipshish), great king, king of Anshan;

the eternal seed of kingship, whose reign the gods Bel (Marduk) and Nabu love, whose k[ingshi]p they desired to their heart’s content”, (RIMB, Cyrus II, 1: 1, 20-22).

The cylinder was discovered during the excavations that were undertaken at Babylon on behalf of the British Museum from February 1879. Jonathan Taylor (referenced below) who presented all of the surviving (and often conflicting) evidence relating to the original discovery of the cylinder, concluded (at p. 89) that it was discovered (in tact) in March 1879. He also looked at the conflicting evidence for the location in which the discovery was made, concluding (at p. 84) that:

✴the cylinder was probably found in a niche in a wall on the so-called Amron mound, having been deposited there during a restoration; and

✴this wall might have belonged to the Esagil (temple of Marduk), but it was more probably part of the Imgur-Enlil, the inner wall of Babylon, since:

•Cyrus’ restoration of this wall was recorded in the inscription (at lines 38-42); and

•we also read that (presumably during this restoration) Cyrus saw:

“... an inscription with the name of Ashurbanipal, a king who had preceded [me]”, (line 43).

This former king was none other than the all-powerful Assyrian King Ashurbanipal (669 - ca. 630 BC), who had (like Cyrus) restored the wall in his capacity as the ‘foreign’ over-lord of Babylon.

As we have seen, Jonathan Taylor (referenced below, at p. 89) established that the cylinder was in tact at the time of its discovery in March 1879. However, he also established that it had been broken soon after, and that:

✴only part of it (in his words, the ‘main fragment’) originally reached the the British Museum (in the following August); while

✴a smaller fragment had found its way to Yale University by 1920.

Irving Finkel (referenced below, at p. 27) recorded that it was only in 1971 that scholars discovered that this ‘Yale fragment’:

“... was part of the British Museum [cylinder] and, what is more, that it actually joined it [as illustrated in Figure 6, at p. 28 and Figure 8, at p. 29]”.

He also noted that, in 2009/10, it had been recognised that two much smaller fragments that had arrived in the British Museum in 1881:

“... come from one large cuneiform tablet that once carried the same text as [that] inscribed on the [cylinder].”

He published (at pp. 16-20) a composite translation of the texts from all of these sources, followed by his translation of the one-line colophon from the tablet: this colophon records the name of the scribe who ‘inscribed the text on the tablet: Qishti Marduk (which was followed by the now-lost name of his father).

Finkel pointed out (at p. 39) that this composite text falls naturally into three distinct consecutive sections:

✴Section 1 (CB: 1-19, written in the third person) describes the circumstances in which Marduk had mandated that Cyrus, king of the land of Anshan, should depose king Nabonidus from the throne of Babylon (see above);

✴Section 2 (CB: 20-36, written in the first person), in which Cyrus used the more extravagant titles discussed above, constitutes Cyrus’ proclamation to his new subjects; and

✴Section 3 (CB: 37-45, written in the third person), largely concerned with Cyrus’ rebuilding/restoration of the urban fabric of Babylon.

He reasonably observed (at p. 33) that this text:

“... conveys a multipurpose message [that] is so well-tailored to a Babylonian readership that it must have seen a wider distribution [than that afforded by its use on] one invisible [foundation deposit].”

He argued (at p. 38) that:

✴the composite text had first been inscribed on a tablet, since:

“... no-one ever composed [as opposed to copied] a cuneiform text of a curvaceous cylinder”;

✴Qishti Marduk copy represented an official copy (rather than a scribal exercise):

“... stemming from a chancery ... where multiple copies of official documents in diverse formats [e.g., tablets, cylinders] were produced”; and

✴the Cyrus cylinder was probably one of:

“... [many] such cylinders [that were] prepared for burial at suitable points in the city’s reconstruction: in each case, the cylinder inscription would be copied from a flat master copy ...”

Finally, he suggested (at p. 40) that the text had been taken from three separate sources:

✴Section 1 came from:

“... a court chronicle or other appraisal of Cyrus’ early reign”;

✴Section 2:

“... represents the words of Cyrus himself, and perhaps ultimately reflects a Persian original”; and

✴Section 3:

“... is a straightforward account [of Cyrus’ urban restoration of Babylon] that derives (at least in some measure) from the earlier text of Ashurbanipal [that was] found in the digging”

In short, Finkel reasonably suggested that important texts from three separate sources were first inscribed on an official tablet that was subsequently copied on:

✴objects such as Qishti Marduk’s tablet, which facilitated the wide public transmission of royal propaganda; and

✴objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder, which were buried as foundation deposits, for the benefit of future generations.

Amélie Kuhrt (referenced below, at p. 88) argued that:

“... it is fair to assume that the concluding line of the Cyrus Cylinder referred to the [return] of Ashurbanipal’s text [to the place] where it had been found and the placing of Cyrus’ inscription next to it.

This actually provides a clue to the ultimate purpose of the Cyrus Cylinder: it was composed to:

commemorate his restoration of Babylon, [in emulation of] that of his predecessor Ashurbanipal;

recount his [peaceful] accession [to the throne of Babylon] and his pious acts [there]; and

demonstrate to subsequent generations his legitimacy as ruler of Babylon.”

She identified three strands of the text that contributed to this characterisation of Cyrus’ rule:

he had been chosen to be king of Babylon by Marduk himself;

he carried out all the religious requirements required of a such a king; and

he was the latest of a long line of benign ‘foreign’ rulers of Babylon, as exemplified by Ashurbanipal.

Cyrus the Great and the Kingship of Sumer and Akkad

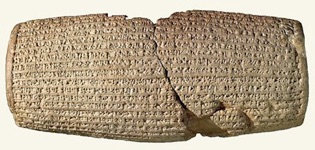

Inscribed clay cylinder known as the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ from the foundations of the wall of Babylon

Image from the site of the British Museum, where the tablet is now housed (BM 90920)

We know from the cuneiform text that is inscribed (in the Babylonian dialect of Akkadian) on what we know as the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ (illustrated above) that, when the Persian king whom we know as Cyrus the Great captured Babylon in 539 BC, he introduced himself to his new Babylonian subjects as:

“... king of the world, great king, strong king, king of Babylon, king of the land of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four quarters (of the world), ... the eternal seed of kingship, whose reign the gods Bel (Marduk) and Nabu love, whose k[ingshi]p they desired to their heart’s content”, (RIMB, Cyrus II, 1: 1, 20-22).

At least three of these royal titles:

✴king of the world;

✴strong king; and

✴king of the four quarters (of the world);

date back to the so-called Sargonic period (ca. 2300), during which Sargon and his successors presided from Akkad over one of the earliest empires known in history.

Interestingly, as Jasmina Osterman (referenced below, at p 63 and note 96), observed, another of Cyrus’ titles, ‘king of Sumer and Akkad’ (LUGAL KUR-šu-me-ri ù ak-ka-di-i), dates back to a slightly later empire, that of the so-called Ur III dynasty (ca. 2100 BC). More specifically, as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2019, at pp. 151-2 and note 409) observed:

“... the founder of [this] dynasty, Ur-Namma, coined for himself a completely new title, which was ‘king of Sumer and Akkad’.”

An important example of this usage is known from the Old Babylonian copy of a Sumerian original that was found in the Mesopotamian city of Isin:

“(I), Ur-Namma, mighty man, king of Ur, king of the lands of Sumer and Akkad (lugal ki-en-gi ki-uri), dedicated (this object) for my life. At that time, the god Enlil gave (?) ... to the Elamites. In the territory of highland Elam, they (Ur-Namma and the Elamites) drew up (lines) against one another for battle. Their (??) king, Puzur-Inshushinak, ... (the cities of) Awal, Kismar, Mashkan-sharrum, the lands of Eshnunna, the lands of Tuttub, the lands of Simudar, the lands of Akkad, all the people ...”, (RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 29, lines 11-23; see also the translation by Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 2008, at p. 35).

It is therefore possible that Ur-Namma, the king of Ur (the city from which he exercised hegemony over the land of Sumer), adopted the additional title ‘king of Sumer and Akkad’ after his ‘liberation’ of the more northerly city of Akkad from the hegemony of the Elamite king Puzur-Inshushinak. Interestingly, is Paul-Alain Beaulieu (referenced below, at p. 52) observed, it was at about this time that Babylon first:

“... emerged from obscurity and became a provincial centre of some consequence, the capital of one of the provinces that formed the core of the Ur III state.”

Now, some 1,500 years later, Cyrus exercised hegemony over Sumer and Akkad by virtue of his conquest of Babylon.

We do not know nearly enough about Cyrus himself to establish how he regarded this Mesopotamian heritage. It is possible that he had simply adapted the titles that the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal had used after he had expelled his brother from the governorship of Babylon in 648 BC: for example:

“I, Ashurbanipal, great king, strong king, king of the world, king of Assyria, king of the four quarters (of the world), offspring of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, governor of Babylon, king of the land of Sumer and Akkad, descendant of Sennacherib, king of the world, king of Assyria”, (RINAP 5: Ashurbanipal 003: see also 004. 005 and 010);

particularly since he recorded in the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ text that he had seen an inscription in Babylon that had been written:

“... in the name of Ashurbanipal, a king who came before [me] ...”, (RIMB, Cyrus II, 1: 1, 43).

However, having said that, it is surely significant that the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ text makes multiple references to the land of Sumer and Akkad (= the territory that we know as Babylonia):

✴before their conquest by Cyrus in 539 BC:

•‘... the people of the land of Sumer and Akkad ... had become like corpses”., (line 11); and

✴after their conquest by Cyrus:

•“the people of Babylon, all of them, the entirety of the land of Sumer and Akkad ... bowed down before him (and) kissed his feet”, (line 18); and

•“the deities of the land of Sumer and Akkad [were able] ... to live in peace in their abodes”, (line 33).

Thus, it seems to me that, at least in the Mesopotamian part of his empire, Cyrus might well have been regarded as the holder of the kingship that had once been held by Ur-Namma.

This brings us to the subject of the present page, the so-called Sumerian King List (SKL): as we shall see, Ur-Namma was the last king recorded in the earliest surviving recension of this list, which was commissioned by his son and successor, Shulgi. This text (of which just over half survives) originally recorded about 80 holders of kingship, dating back to the mythical Gushur, who had ruled from Kish when kingship had first descended from heaven. At least by the time of Ur-Namma, the kingship in question was obviously that of Sumer and Akkad. Thus, by adopting this title, Cyrus (or, at least, his Babylonian advisors) laid claim to this Mesopotamian heritage (alongside his heritage from his own forebears, who were identified in the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ text as great kings of Anshan).

Abbreviations:

RIMB 8 = From Royal Inscriptions of Babylonia online

Other references:

Osterman J., “From ki-en-gi to Šumerum: How Sumer was Created ?”, Radovi HSP, 54:3 (2022) at pp. 39-72

Beaulieu P.-A., “A History of Babylon (2200 BC - AD 75)”, (2018) Hoboken, NJ

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2017) Boston and Berlin

Finkel I., “The Cyrus Cylinder: the Babylonian Perspective”, in:

Finkel I. (editor), “The Cyrus Cylinder: The Great Persian Edict from Babylon”, (2013) New York, at pp. 16-51

Taylor J., “The Cyrus Cylinder: Discovery”, in:

Finkel I. (editor),“The Cyrus Cylinder: The Great Persian Edict from Babylon”, (2013) New York, at pp. 51- 98

Frayne D. R. , “The Zagros Campaigns of the Ur III Kings”, Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies, 3 (2008) 33-56

Kuhrt A., “The Cyrus Cylinder and Achaemenid Imperial Policy”, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, 25 (1983) 83-9.