Roman Pre-History

Archaic Inscriptions

Roman Pre-History

Archaic Inscriptions

Inscribed Cippus under the Lapis Niger

Model of the inscribed cippus that was discovered under the lapis niger

Now in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Baths of Diocletian, Rome

From this site by René Seindal

This inscription (CIL VI 36840) is on a cippus that was discovered in 1899 under the later lapis niger (black marble pavement) in front of the Curia Julia in the Forum. It is usually dated to the first half of the 6th century BC and, as Christopher Lyes (referenced below, at pp. 45-6) observed, it:

“... has been described as Rome’s oldest [surviving] public document.”

It uses an archaic Latin alphabet, and its 16 line were read from the bottom to the top and then back to the bottom of the cippus. Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at pp. 73-4) observed that:

“Although the precise meaning of the document is uncertain, [not least because the upper part of it is missing], four words are beyond dispute:

✴ [in line 2], sakros (= classical Latin sacer, masculine nominative singular), meaning sacred or, more likely, accursed, thus alluding to the imposition of a religious sanction upon an offender of this law;

✴[in line 5], recei (= classical Latin regi, indirect object in the dative case of rex) ... thus referring to either the Roman king or the rex sacrorum of the fledgling Republic;

✴[in lines 8-9], kala- torem (= classical Latin calatorem, direct object in the accusative case), meaning herald or crier ... ; and

✴[in lines 10-11], ioux- menta (= classical Latin iumenta, nominative or accusative neuter plural), meaning beasts of burden and hence also wagons, carriages or vehicles.

Since [the] cippus ... was not taken down and solemnly buried until imperial times, it must have stood near the Rostra throughout the Republic and was therefore on permanent display for inspection by anyone interested in it.”

He pointed out (at p. 74):

“Ancient Roman historians and antiquarians, who probably had the benefit of examining the text in an undamaged state, thought that this inscribed stone was a tombstone, one thing that it certainly [was] not. At least three different views were offered concerning the identity of the alleged grave’s occupant [Romulus, Faustulus or Hostus Hostilius, discussed in turn below]. ... All three of these conjectures associate the inscribed stone with the reign of Romulus, thereby dating it, [incorrectly], to the second half of the 8th century BC.”

Grave of Romulus ?

As we saw above, according to Verrius Flaccus, who would have been writing within decades of the laying of the lapis niger, this pavement indicated:

“... a place associated with death, because the death of Romulus was assigned to it.”

This association might well have arisen because (as Gary Forsythe suggested) his sources probably believed that the cippus was an ancient tombstone. Verrius’ contemporary, the poet Horace, in a work of 30 BC, warned that:

“A barbaric conqueror will tread on [Rome’s] ashes, his horsemen will trample on the city with clattering hooves, and ... he will scatter in his arrogance the ossa Quirini (bones of Quirinus, the deified Romulus) that are now sheltered from wind and sun”, (‘Epodes’, 16: 10-14, translated by Niall Rudd, referenced below, at p. 307).

Horace might well have imagined that the ossa Quirini were ‘now sheltered‘ by the lapis niger. In his commentary on this passage in the 3rd century AD, Porphyry observed that Horace’s prophecy had been formulated:

“...as if Romulus [had been buried rather than taken up to] Heaven or dismembered [by his enemies]. In fact Varro [also] states that Romulus had been buried behind the Rostra”, (translated by Diana Guarisco, referenced below, at p. 14).

A probably later commentary known as the Pseudo Acronian scholia recorded that:

“Most people say that Romulus was buried at the Rostra and that, in remembrance of this, there were two lions, just like the ones which today we see on the tombs, and that is because of this that dead men are praised before the Rostra”, (translated by Diana Guarisco, referenced below, at p. 14).

Thus, we can trace the tradition that the inscribed cippus marked the grave of Romulus/ Quirinus back to Varro, who died very shortly after the rebuilding of the Curia Julia began in 43 BC.

Grave of Faustulus ?

According to tradition, Faustulus was the herdsman who had rescued the abandoned Romulus and and raised them as his own. According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, when they later argued about which of them would found the settlement that became Rome:

“... a sharp battle ensued, in which many were slain on both sides. In the course of this battle, as some say, Faustulus, ... wishing to put an end to the strife of the brothers and being unable to do so, threw himself unarmed into the midst of the combatants, seeking the speediest death, which duly occurred. Some say also that the stone lion that stood in the principal part of the Forum near the Rostra was placed over the body of Faustulus, who was buried by those who found him in the place where he fell”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 87: 2).

This lion must surely have been one of the two lions that, according to the Pseudo Acronian scholia (above), had marked what Horace had believed to be the grave of Romulus/ Quirinus.

Grave of Hostus Hostilius ?

According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Hostus Hostilius was the grandfather of Tullus Hostilius, traditionally the third king of Rome. He came from:

“... Medullia, a city that had been built by the Albans and made a Roman colony by Romulus after he had forced its capitulation. [Hostilius was a] man of distinguished birth and great fortune who had moved to Rome and married a Sabine woman ... This man, after taking part with Romulus in many wars and performing mighty deeds in the battles with the Sabines, died, leaving only a young son, and was buried by [beside ??] the kings in the principal part of the Forum and honoured with a monument and an inscription testifying to his valour”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 1: 2).

Dionysius’ source(s) for this tradition very probably considered the inscribed cippus to have been the epitaph of Hostus Hostilius.

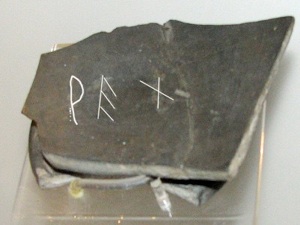

Inscribed Bucchero from the Regia

Inscription from the Regia, now in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Baths of Diocletian, Rome

Inscription picked out in white

This inscription (CIL I2 2830), which dates to the period 530-500 BC, is on a fragment of a bucchero bowl that was discovered in 1899 under the Republican pavement of the Regia.

Read more:

C. Lyes, “Rethinking the Lapis Niger”, Classics Students' Journal, 1 (2017) 45-63

G. Forsythe, “A Critical History of Early Rome: From Prehistory to the First Punic War”, (2005) Berkeley Los Angeles and London

Linked pages:

Return to Regal Period