Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Etruscan League and Fanum Voltumnae (431 - 389 BC)

Linked pages: Etruscan Federation and Fanum Voltumnae (431 - 389 BC);

Roman Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)

Etruscan League and Fanum Voltumnae (431 - 389 BC)

Linked pages: Etruscan Federation and Fanum Voltumnae (431 - 389 BC);

Meetings at Fanum Voltumnae

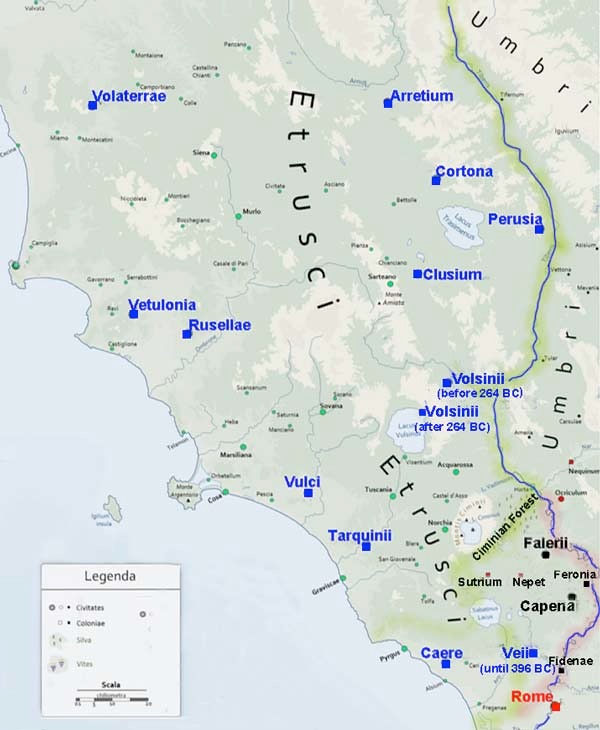

Blue = likely candidates for the duodecim populos (twelve peoples) of Etruria prior to the conquest

Fidenae: usually an ally of Veii until it fell to the Romans in 426 BC

Falerii and Capena: allies of Veii until is fall in 396 BC

Sutrium and Nepet: could call on Roman support from at least 386 BC

Livy mentioned five pan-Etruscan meetings that were held at a place that he called fanum Voltumnae (shrine of Voltumna) in the period 434 - 386 BC, and noted that the first of was convened at the request of Veii and with the agreement of duodecim populos (the twelve peoples). The identities of the other eleven principal members of what is conventionally referred to as the Etruscan League are unknown: the likely candidates (marked in blue on the map above) are taken from Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 403). Unfortunately, Livy is the only surviving source for the existence of the fanum Voltumnae and he did not record its location: as we shall see, modern scholarship generally places it at Velzna (Latin Volsinii, modern Orvieto) until the Romans destroyed this city and relocated its inhabitants in 264 BC. More importantly, Livy did not explicitly define its function within pan-Etruscan society, which means that we are unusually reliant on the circumstantial evidence that can be extracted from Livy’s account of this period.

Prior Events (438-7 BC)

The first of Livy’s five meetings at the fanum Voltumnae took place shortly after a momentous event in the history of the Romans’ relations with Veii: according to Livy, in 438 BC:

“... Fidenae, a Roman colony [sic.], defected to Lars Tolumnius and the Veientines. A greater wickedness was then added to this defection: on Tolumnius’ orders, the Fidenates killed the Roman envoys, C. Fulcinius, Cloelius Tullus, Sp. Nautius, and L. Roscius, who [had been sent to Fidenae in order establish] the reason for [the putative rebellion there]”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 17: 1-6).

This crime was long-remembered in Rome:

✴Livy (‘History of Rome’, 4: 17: 1-6) recorded that public statues of the murdered ambassadors had been set up on the Rostra in the forum ; and

✴Cicero (‘Philippics’, 9: 4) recalled having seen them there before they were removed in the late 1st century BC.

According to Livy, the Romans responded to the crime by attacking Veii and Fidenae, who were reinforced by an army from nearby Falerii. Mam. Aemilius Mamercinus was appointed as dictator, and he secured a great victory in which:

✴a military tribune, A. Cornelius Cossus, killed Lars Tolumnius in single combat; and

✴Fidenae fell to the Romans.

Then:

“ Successful on every front, [Mamercinus] returned to the City and celebrated a triumph, ... [in which] the greatest spectacle ... was [offered by] Cossus, bearing the spolia opima, [the armour that he had stripped from Tolumnius]”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 20: 1-2).

Livy himself subsequently dealt with the uncertainty as to whether Cossus had killed Tolumnius:

✴as military tribune in 437 BC (as above);

✴as consul in 428 BC; or

✴as military tribune with consular power and master of horse to Mamercinus (now dictator for the third time) in 426 BC.

However, for our purposes in this page, it is sufficient to note that Livy’s first of the meetings at the fanum Voltumnae (in 434 BC) followed:

✴the Romans’ capture of Fidenae in 437 BC (albeit that their hold on it remained precarious); and

✴Cossus killing of Tolumnius, if not in 437 BC, then in subsequent battles in either 428 or 426 BC.

Livy’s Two First Mentions of Fanum Voltumnae (434 and 432 BC)

According to Livy, after the fall of Fidenae in 435 BC:

“There was consternation in Etruria:

✴the Veientines, [in particular], were terrified by the fear of a similar destruction; and

✴the Faliscans [feared retribution because] they had started the war in alliance with the Fidenates, albeit that they had not helped them in their revolt.

The two states consequently sent ambassadors around duodecim populos (the twelve peoples) and obtained their agreement to the convening of omni Etruriae concilium (a council of all the Etruscans) at the fanum Voltumnae”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 23: 4-5).

Livy seems to suggest that Faliscans (like the Veientines) regularly attended the meetings at the fanum Voltumnnae at this time. While this is possibly correct, they would not have featured among Livy’s ‘twelve peoples’ of Etruria: as Timothy Cornell (referenced below, at p. 313) pointed out, the people of Falerii and nearby Capena:

“... spoke a dialect of Latin and were ethnically distinct from the Etruscans.”

News of the imminent meeting caused alarm at Rome, and the Senate:

“... [fearing that] a great uprising was imminent,... ordered that Mam. Aemilius [Mamercinus] should be appointed to his second dictatorship, [his first, as we have seen, being in 437 BC]. ... [Preparations for war were intensified], since the [potential] danger from the whole of Etruria was so much greater than that from [Veii and Falerii alone]”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 23: 5-6).

However, this proved to be a false alarm:

“The meeting [at the fanum Voltumnae] passed off more quietly than anybody expected. Information was brought by traders that help had been refused to the Veientines; they were told to prosecute with their own resources a war that they had begun on their own initiative, and not, now that they were in difficulties, to look for allies amongst those whom, in their prosperity, they refused to take into their confidence”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 24: 1-2).

The implication seems to be that Lars Tolumnius had not consulted the other eleven principal members of the League before inciting the putative rebellion at Fidenae and ordering the murder of the Roman ambassadors.

The Veientines apparently tried to incite pan-Etruscan action against Rome in 432 BC, again without success:

“Projects of war were discussed:

✴in the councils of the Volsci and Aequi, [prior to their raising of armies using leges sacratae and their defeat on the Algidus in 431 BC]; and

✴in Etruria at the fanum Voltumnae. There, the question was adjourned for a year and a decree was passed that no [subsequent] council should be held until the year had elapsed, in spite of the protests of the Veientines, who declared that they now faced the fate that had [already] overtaken Fidenae”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 25: 6-9).

The Romans seem to have sent colonists to Fidenae after their victory of 434 BC, but it retained its nominal independence. This situation was destabilised in 428 BC, when Fidenae supported a Veientine incursion into Roman territory, and a Roman attempt to retaliate in 426 BC by sending out an army under three consular tribunes ended in defeat. According to Livy, the Veientines, who were:

“... elated by their success, ... sent envoys round to the peoples of Etruria, boasting that they had defeated three Roman generals in a single battle. Although they could not induce the national council to join them, they attracted volunteers from all quarters by [holding out] the prospect of booty”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 31: 6-7).

The Romans appointed Mamercinus to his third dictatorship, and he appointed Cossus (then consular tribune) as his master of horse. He engaged with and comprehensively defeated this Etruscan army at Fidenae, which passed definitively into Roman hands. Veii then agreed a 20-year truce with Rome.

Siege of Veii (406 - 396 BC)

Livy’s Third Mention of Fanum Voltumnae (405 BC)

Rome’s truce with Veii ended in 407 BC, at which point, the Romans began their ten-year war with Veii

Yet again, the putative Etruscan league decided not to intervene: in 405 BC:

“... a well-attended council of the Etruscans at the fanum Voltumnae failed to agree on whether the whole [Etruscan] nation should join in a war to defend Veii”, (‘History of Rome’, 4: 61: 2-3).

As the siege continued, the Veientines tried again in 403 BC to secure the help of the other Etruscans. Livy’s account of this meeting (which must also have been held at the fanum Voltumnae, although Livy did not specifically say so) is particularly illuminating. Having mentioned the elections of the consular tribunes for 403 BC at Rome, Livy continued:

“ The Veientines, on the other hand, because they were tired of the annual competition for office that had periodically been the cause of discord, elected a king”, (‘History of Rome’’, 5: 1: 2).

As we have seen Lars Tolumnius had apparently been killed at some time in 437-26 BC, so Livy must have believed that Veientines had temporarily dispensed with the monarchy at this pont, only to revert to it in 403 BC. He claimed that:

“ This action offended the feelings of the peoples of Etruria, who hated kingship in general and this king in particular, ... since he had forcibly and sacrilegiously broken up a religious festival: angry at his rejection when the votes of the twelve peoples preferred a man other than himself as sacerdos (priest), he had suddenly led off the performers (most of whom were his slaves) in the middle of the games. Consequently, the Etruscans, who above all other peoples are devoted to religious matters because they excel in the art of attending to them, decided to refuse their help to the Veientines as long as they were subject to a king”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 1: 2-8).

From this, we learn that:

✴by this time, the ‘twelve peoples’ elected a sacerdos (priest) from among their respective magistrates during their presumably annual assemblies;

✴these putative annual meetings also involved games and theatrical performances, over which the newly-elected priest presumably presided; and

✴these games and theatrical performances were held to be sacred (since the disruption by the king of Veii in 403 BC had been considered to have been impious).

Henk Versnel (referenced below at pp. 275-6) argued that:

“The object of the annual meeting was the election of what in the republican period is called a sacerdos ... Since, according to Livy, it was a king of Veii who ... competed for this office [in 403 BC], the ambiguous nature of this function is at once clear. Here we see in one person two spheres overlapping: the religious and the political:

✴During the royal period, the twelve cities ... elected one supreme king who, by having twelve lictors carrying fasces, one on behalf of each city, united the authority in one hand.

✴The sacerdos was the religious successor of this supreme king.”

Despite the fact that:

✴the ‘twelve peoples’ had decided against the sending of help to Veii at this particular meeting of the Etruscan council; and

✴reports from Veii suggested that the situation there was quiet;

the Romans remained on the alert, and:

“... because it was reported that the subject of Veii came up at every meeting [of the Etruscan council, they] constructed their earthworks in such a way that there were fortifications on two fronts:

✴some were directed towards Veii, to oppose sorties by the townsfolk; and

✴others faced Etruria, to obstruct any help that might come from there”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 1: 2-8).

The beleaguered Veientines continued their resistance and, when the Romans realised that the siege was to be continued through another winter, support for it dwindled. However, Ap. Claudius Crassus, one of the consular tribunes of 403 BC, successfully dispelled this dissent, pointing (inter alia) to:

“... the risk that [would be taken] by postponing the war. Do the frequent councils in Etruria about sending help to Veii allow us to forget this? As the situation is now, the Etruscans are angry and resentful, saying they will not send help. As far as they are concerned, we may capture Veii. But who would guarantee that, if the war is postponed, they would continue to be of the same mind ? If you grant a respite, there is bound to be greater and more frequent diplomacy. Furthermore, the thing that now offends the Etruscans, namely the election of a king at Veii, could be changed with the passing of time ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 5: 8-12).

In this passage, Livy seems to imagine that the ‘twelve peoples’ met on an ad hoc basis during potential military emergencies. Marco Ricci (referenced below, at pp. 16-7) summarised Livy’s accounts as follows:

“The picture that emerges is ... that of a confederation of city-states, born above all out of military necessity, essentially defensive but also sustained by deeper cultural values than those of a purely military alliance” (my translation).

As it happens, aid for Veii arrived in 402 BC, but not from their fellow Etruscans: Livy explained that, since Falerii and Capena:

“...were nearest to [the theatre of war], they believed that, if Veii fell, they would be the next on whom Rome would make war. ... So, they ... swore alliance with each other, and their two armies arrived unexpectedly at Veii”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 8: 5-6).

It seems that, as they unexpectedly marched towards the besieged city:

“... they attacked ... [one of the Roman camps], causing great terror because the Romans believed that

the whole of Etruria had been summoned from their cities and was coming with a massive force. The same belief aroused the Veientines in their city, and the Roman camp was attacked on two fronts”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 8: 7).

The result for the Romans was an ignominious (albeit not definitive) defeat.

Livy’s Fourth Mention of Fanum Voltumnae (397 BC)

The Romans managed to continue the siege of Veii despite continuing internal tensions at home. Finally, in 397 BC:

“... the Etruscan council met at the fanum Voltumnae. When the Capenates and Faliscans demanded that there be a common resolution and plan for all the people of Etruria to rescue Veii from

siege, they received the reply that;

✴[on previous occasions. the majority of the Etruscans] had refused the Veientines’ request [for help] because they[had not been consulted before the outbreak of hostiliies; but

✴now, their own misfortunes essentially denied the request, since there was an unknown race [i.e., the Gauls] in much of Etruria, new settlers [whose intentions had yet to be determined].

Nevertheless, because of regard for the blood and name of their kinsmen and the dangers facing them, they granted that hey would not prevent any young men who wanted to volunteer for that war from doing so”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 17: 7-10).

It seems that the Romans were concerned that they had so far failed to take Veii because they had offended the gods and frantically searched for the appropriate way in which they could be propitiated. Concern turned to panic in early 396 BC when the Faliscans and Capenates ambushed two of the consular tribunes, killing one of them. However, by this time, the required acts of propitiation had undertaken ( the Latin festival had been repeated and the excess water had been drawn from the Alban lake). Finally:

“... the fates were attacking Veii. And so, the dux (commander) who was fated to destroy that city and save his country, M. Furius Camillus, was appointed dictator ... The change of commander suddenly changed everything”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 19: 1-3)

Camillus was able to take Veii by secretly building a tunnel under the walls and taking it by surprise and then returned to Rome in triumph. Veii and all its territory now became part of the Roman State. However, internal politics then led to Camillus’ exile to Ardea in Latium.

Livy’s Fifth (and Last) Mention of Fanum Voltumnae (389 BC)

In 390 BC (by Livy’s reckoning), the Gauls who had been disrupting the lives of the Etruscans for at least seven years (see above), defeated the Roman army on the Allia, sacked Rome and extracted a huge amount of gold as ransom before departing for pastures new. Livy (who claimed that Camillus had been recalled from exile in time to block the payment of ransom and deliver the City from the Gauls) reported that, although the Gallic crisis had receded by 389 BC, the Romans:

“... were not ...long left undisturbed:

✴on the one side, the Volscians, their ancient foes, had taken up arms in the determination to wipe out the nomen Romanum (Roman name);

✴on the other side, traders were reporting that Etruriae principum ex omnibus populis (all the principal peoples of Etruria) were plotting war at the fanum Voltumnae; and

✴still further alarm was created by the defection of the Latins and Hernicans, [despite the fact that] these nations had never wavered in their loyal friendship with Rome ... [since] the battle of Lake Regillus [in ca. 500 BC].

As so many dangers were threatening on all sides, ... the Senate decided that Rome should be defended under the auspices of the man by whom it had been recovered [from the Gauls], and that M. Furius Camillus should be nominated dictator [for the third time]”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 2: 1-5).

According to Livy, when Camilius had marched against the Volsci, he left two military divisions behind:

“He stationed one in the [recently-acquired] Veientine territory fronting Etruria ... ”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 2: 7).

The need for such a strategy was soon demonstrated: while Camillus was still in Volscian and Aequan territory, news reached Rome to the effect that:

“... a terrible danger was threatening: Etruria prope omnis (nearly the whole of Etruria) was in arms and was besieging Sutrium, socio populi Romani (a city in alliance with Rome)”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 3: 1-2).

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at p. 347) observed that Sutrium (and nearby Nepete) stood on land that must have been confiscated from Falerii in 394 BC, which would explain why the people of Sutrium now enjoyed the protection of Rome. However, since Camillus was fully occupied against the Volsci and the Aequi, his arrival on the scene was almost too late because:

“... the people of Sutrium had made a conditional surrender of their city. As the mournful procession set forth ... Camillus and his army happened ... to appear on the scene. ... He ordered the [fleeing people] to remain where they were and ... marched to Sutrium, [which he took] before the Etruscans could [prepare its defence]. Thus, Sutrium was captured twice in the same day ... Before nightfall the town was returned to its people, uninjured and untouched by all the ruin of war...”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 3: 2-10).

This is the first time and only time that Livy described a Roman engagement with a pan-Etruscan army that had been raised in pursuance of a plan that had been agreed at a meeting of the ‘twelve peoples’ at the fanum Voltumnae. It is therefore comes something of an anticlimax to read that Camillus expelled the Etruscan who had occupied Sutrium as soon as he arrived, at which point, they seem to have withdrawn, leaving Camillus free to return to Rome for his triple triumph. Indeed, it is likely that both:

✴the meeting at the fanum Voltumnae; and

✴the raising of a pan-Etruscan army that expelled Rome’s allies from Sutrium;

are both inventions to lionise Camillus. Having said that, Stephen Oakley (referenced below, 1997, at pp. 347-8 and note 56) argued that:

“Although the details of the engagement at Sutrium are highly suspect, the underlying fact that the Etruscans attempted to profit from Rome’s distractions should not be doubted.”

However, I suggest that, at this time:

✴Caere would still have been a Roman ally;

✴the Etruscan cities north of the Ciminian forest are unlikely have fought the Romans; and

✴the most likely invaders of Sutrium are the Faliscans and the Etruscans of Tarquinia and (perhaps) Vulci.

Veltune/ Voltumna

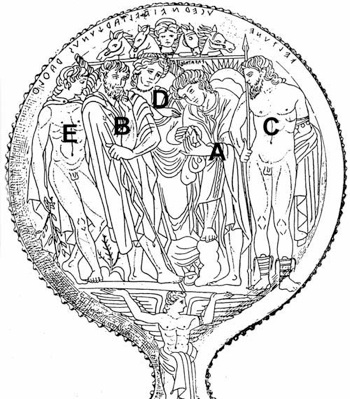

Bronze mirror (early 3rd century BC) from Tuscania

Museo Archeologico, Florence

A = ‘Pava Tarchies; B = ‘Avl Tarchunus’ ; C = ‘Veltune’ (C); D = ‘Ucernei’ ; E = ‘Rathlth’

Livy’s records of the fanum Voltumnae are also the only surviving evidence for an Etruscan deity that the Romans knew as Voltumna. The original Etruscan name for this deity might have been “Veltune”, who was identified by inscription on the mirror above: thus, Nancy Thomson de Grummond (referenced below, at p. 29) observed that the figure to the right, who is labelled Veltune, is:

“... often equated with the Etruscan god whom the Romans called Vertumnus [and whom Livy called Voltumna].”

She described the scene depicted in this mirror as follows:

✴At the centre, a young haruspex, who is identified by inscription as ‘pava tarχies’ and who wears wearing a conical cap, ritually examines the liver of an animal.

✴He is watched intently by an older priest to his right, whose similar conical hat is pushed back and who is identified as ‘avl tarχunus’.

✴At the extreme right of the composition, Veltune, who stands behind ‘pava tarχies’ and looks over his shoulder, is depicted as nude and bearded and holds a spear vertically in his right hand.

She observed that:

“No better explanation has been found [for this iconography than that of Massimo Pallottino, referenced below]: we have here the myth of Tages (pava may mean puer or child [and] tarχies could become Tages in Latin) instructing Tarchon [the legendary founder of Tarquinia], or perhaps his son, whose name would then be avl, in haruspicina [the art of divination using animal entrails].”

She cited (at p. 27) Verrius Flaccus, epitomised by Festus, to the effect that the founder of the Etruscan religion was:

“... a boy named Tages, the son of Genius, [and] grandson of Jupiter, [who] is said to have given the discipline of divination to the twelve peoples of Etruria” (‘De verborum significatu’, 492 Lindsay).

She therefore pointed out (at pp. 29-30) that:

“... [since] some have argued that Veltune is simply another name for [Tinia/Jupiter - see below], it is possible that we have [in the figure of Veltune in the mirror] the god who was the grandfather of [‘pava tarχies’, the young Tages].”

She also reproduced (as source II: 1, p. 191) a surviving fragment of a Latin translation of one of the prophecies of the Etruscan nymph that the Romans called Vegoia, which was addressed to an Etruscan called Arruns Veltymnus, pointing out (at p. 30) that:

“The name ‘Veltymnus’ is remarkably similar to Veltune on the [mirror from Tuscania]: perhaps ... Arruns had a special relationship with this god.”

It seems that, according to Roman tradition, Veltune (or perhaps Velthumna) had been adopted in Rome as Vertumnus at an early date. In the 1st century BC, Propertius wrote an elegy in the form of a monologue that was delivered by a bronze statue of this deity that stood on the Vicus Tuscus (Etruscan Way) in Rome, in which he (i.e. the statue) spoke of his ancient Etruscan origins:

“And you, Rome, gave rewards to my Tuscans (from whom the Vicus Tuscus takes its name today) at the time that Lycomedius came with armed allies and crushed fierce Tatius. I saw the broken ranks, the abandoned weapons, and the enemy turn their backs in shameful flight. Seed of the Gods, grant that the toga’d crowds of Rome may pass before my feet forever. ... I was [originally] a maple sapling, cut by a swift sickle: before Numa, I was a humble god in a grateful city. But you, Mamurius, creator of my bronze statue, may the Oscan earth never spoil your skilful hands, which were able to cast me for such adaptable use. It is a single statue, but the honour given to it is not” (‘Elegies’ 4.2).

Thus, Vertumnus (through his statue in the Vicus Tuscus) claimed to have seen an Etruscan army led by ‘Lycomedius’ [more usually identified as Caeles Vibenna, as in Varro, below] that came to the aid of Romulus against the Sabines under King Tatius. Originally, this deity had been represented on the Vicus Tuscus by a wooden statue. However, in the reign of Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome (traditionally 715-673 BC), the mythical Mamurius Veturius had executed the bronze statue that addressed the crowd in Propertius’ time.

Varro also referred to this statue (which he called Vortumnus) in another text that related it (although less directly) to the Etruscan presence in early Rome:

“ ...the Caelian Hill [was] named from Caeles Vibenna, an Etruscan leader of distinction, who is said to have come with his followers to help Romulus to defeat the Sabine Titus Tatius. The [Etruscan] followers of Caeles are said to have been brought down from this hill into the level ground after his death, because they were in possession of a location that was too strongly fortified and their loyalty was doubted. The Vicus Tuscus [on this lower ground] was named for them; and it is said that the statue of Vortumnus stands there because he is ‘deus Etruriae princeps’ [usually translated as ‘the most important god of Etruria’]” (‘De Lingua Latina’, 5:46).

Tinia Velthumna ?

This last remark of Varro’s is somewhat surprising, since the most important of the Etruscan deities was surely Tinia (Greek Zeus, Roman Jupiter or Jove). Seneca, for example, was explicit:

“The ancient sages recognised the same Jupiter that we do, the guardian and ruler of the universe, its soul and breath, the maker and lord of this earthly frame of things, to whom every name of power is appropriate. ... The Etruscans thought so too. They said [that thunder] bolts were sent by Jove, just because nothing is performed except by his power” (‘Naturales Quaestiones’, 2:45, search on ‘Etruscans’).

In view of this, Gérard Capdeville (referenced below. at p. 122) asked rhetorically:

“... who else [but Tinia] could be the supreme god of the Etruscans, and how should we situate Vertumnus (i.e Voltumna ...) in relation to him?” (my translation).

He pointed out that some scholars resolved this by proposing that Voltumna was an epithet applied to Tinia at the Fanum Voltumnae. Capdeville himself (at p. 124) rejected that suggestion and alternatively suggested (at p. 126) that, when Varro used the word ‘princeps’, he was simply recording that Vortumnus/ Vertumnus had been the first Etruscan deity to be introduced at Rome. However, later scholars have tended to accept the earlier hypothesis:

✴Francesco Roncalli (referenced below, p 220) concluded that:

“Today, the opinion most widely held by scholars (albeit that it is not unanimous) is that the term ‘Velthumna’ belongs in realty in the full name of the deity: [it was] not isolated ... but rather combined with the name Tinia ...(thus Tinia Velthumna)” (my translation).

✴As noted above, Nancy Thomson de Grummond (referenced below, at p. 29) associated Veltune in the mirror from Tuscania with Jupiter [i.e. Tinia], the grandfather of Tages.

✴Giorgio Ferri (referenced below, at p. 143), who acknowledged (in note 137) Capdeville’s contrary view, nevertheless asserted that:

“Voltumna is ... very probably to be identified as none other than Tinia, the supreme Etruscan deity and the counterpart of Roman Jove. Voltumna perhaps originally constituted only an epithet (as in Tinia Velthumna) that was applied to Tinia in order to characterise his particular function at Volsinii ...” (my translation).

✴Giovanni Colonna (referenced below, at p. 205) referred to the:

“... substantial accord [among scholars] in considering ... Voltumna ... to be an Etruscan epithet of Tinia ... that alludes to the chtonic character of the deity [i.e. his role at Volsinii - deduced by Colonna - as a god of the underworld]” (my translation).

Volsinii

Orvieto: the site of Etruscan Volsinii?

As noted above, Livy, the only surviving source for the fanum Voltumnae, never recorded its location. However, Propertius, in the elegy already quoted in part above above, had the statue of Vertumnus in Rome insisting:

“I am a Tuscan born of Tuscans, [but] do not regret abandoning Volsinii’s hearths in battle” (‘Elegies’ 4.2).

Volsinii had been the last of the Etruscan cities to fall to Rome (in 280 BC). The Romans sent the consul Marcus Fulvius Flaccus to suppress slave revolt that broke out there in 264BC, after which he razed Volsinii to the ground and moved its surviving people to a new and less defensible site on the shores of Lake Bolsena. Festus (‘De verborum significatu’, 228 Lindsay) recorded that Flaccus was portrayed in the temple of Vertumnus on the Aventine Hill, wearing the purple toga that signified his triumph of 264 BC. Thus, we might reasonably assume that:

✴the fanum Voltumnae, which had been presided over by the Etruscan precursor of Vertumnus, had been near Volsinii;

✴like Volsinii itself, it had suffered at the hands of Marcus Fulvius Flaccus in 264 BC; and

✴Flaccus had appropriated its presiding deity, who did not regret his move to Rome, where he had been absorbed into the Roman cult of Vertumnus.

The subject of the location of Etruscan Volsinii has long been debated by scholars. In 1828, Karl Otfried Müller (referenced below) expressed the opinion that it had stood on the naturally-fortified site of modern Orvieto (illustrated above). A number of significant Etruscan remains were discovered there in the following two years and, by the time that George Dennis (referenced below) visited Orvieto in 1842, the city’s Etruscan roots were beyond doubt. However, as Dennis observed (at p. 527), there was still no consensus as to the original name of this Etruscan city:

“The antiquity of Orvieto is implied in its name, a corruption of Urbs Vetus. But, as to its original appellation, we have no clue ....:

•Müller [as above] broaches the opinion that this Urbs Vetus was none other than the ‘old city’ of Volsinii, which was destroyed by the Romans on its [re-]capture [in 264 BC]. But the distance of 8 or 9 miles from the new town [i.e. Bolsena, the site of what Müller had dubbed the ‘new’ Roman city of Volsinii] is too great to favour this opinion.

•Niebuhr [Barthold Georg Niebuhr, referenced below] suggests, with more probability, that [the annular cliff on which Orvieto stands] may [have been] the site of Salpinum, which [according to Livy] ... assisted Volsinii in her war with Rome [in 392 BC].”

William Harris (referenced below, at p. 113) revisited this question in the light of the more extensive archeological record that had become available by 1965:

“Orvieto is probably the site of Etruscan Volsinii. This identification, which goes back to K. O. Müller, has been assailed by Raymond Bloch in a series of articles on the archaeology of Bolsena. It is, however, supported by the evidence of both sites: the finds at Orvieto, notably the rich groups of 6th and 5th century tombs recently excavated by Mario Bizzarri in the Crocefisso del Tufo cemetery, easily outweigh the small quantity of early material which has emerged from the Bolsena site.”

The question is still not completely resolved: see, for example, this book by Angelo Timperi (which is sadly out of print and which I have not been able to consult). However, it is probably fair to say that most scholars now accept Müller’s intuition: for example, Pierre Gros (referenced below), who is an expert in the archeology of Bolsena, presented the arguments for Orvieto in persuasive terms. He concluded (at p. 20) that:

“... the body of evidence [that he had presented in his paper] makes it likely that Etruscan Volsinii was located on the rock of Orvieto. [However], this does not mean that Roman Volsinii [on Lake Bolsena] was established in a previously-unoccupied location.”

Francesco Roncalli (referenced below) referred to three inscriptions from Volsinii that recorded other ‘double’ names for Tinia:

✴“... two altars [bear] the formula tinia tinscvi ...:

-one, in tufa, from the area of [the church of] San Giovanni Evangelista; and

-the other in nenfro [a volcanic rock], probably from under the transept of the Duomo” (my translation, from p. 221); and

✴“... [the formula tinia calsuna] is painted under a black glazed drinking cup of [the 3rd century BC ?] that was found in the area of the [so-called] Tempio del Belvedere” (my translation, from p. 222).

It is important to note that Livy is the only source we have for the existence of the fanum Voltumnae, and that his records all date to the period 434-389 BC. We do not know whether this was the only location used for the meetings, even during this period. In addition, although Livy says that the assemblies at the fanum Voltumnae involved 12 states, he only mentioned three of them (Veii, Capena, and Falerii) by name in this context: thus, he recorded that, in 397 BC:

“... the national council of Etruria met at the fanum Voltumnae. The [people of Capena and Falerii] demanded that all the peoples of Etruria should unite in common action to raise the siege of Veii; they were told in reply that ... unfortunate circumstances ... compelled [the other participants] to refuse. The Gauls, a strange and unknown race, had recently overrun the greatest part of Etruria, and they were not on terms of either assured peace or open war with them. They would, however, do this much for those of their blood and name ... if any of their younger men volunteered for the war they would not prevent their going” (‘History of Rome’, 5: 17: 7-10).

In fact, despite their stout support of Veii, the people of Capena and Falerii were ethnically distinct from the Etruscans, and spoke a dialect of Latin known as Faliscan. Furthermore, we have no record of the Etruscan League taking concerted military action: thus, after the appeal described here, Rome was able to take Veii, Capena and Falerii in successive years in 396-4 BC. Livy last reference to this federal sanctuary related to 389 BC, when:

“... some traders brought [intelligence to Rome] that a conspiracy of the leading men of Etruria from all the states had been formed at the fanum Voltumnae”, (‘History of Rome’, 6: 2: 2).

End of the Etruscan League

The Roman conquest of Etruria began with the fall of Veii in 396 BC (as mentioned above) and ended with the fall of Volsinii in 280 BC. It is possible that the Etruscan League survived in some form during this period, even though its component cities were falling like dominoes before the Roman advance. If so, it could surely not have survived the destruction of Volsinii after the slave rebellion of 264 BC: as Marco Ricci (referenced below, at p. 17) observed:

“Given the purpose for which the confederation was formed, it could not, of course, survive the incorporation of Etruria into the orbit of Rome. Thus, after the fall of Volsinii and its destruction in 264 BC, it seems likely that federal meetings were prohibited” (my translation).

Fate of Voltumna

As noted above:

✴Propertius was surely referring to the battle of 264 BC when he had Voltumna/ Vertumnus assert:

“I am a Tuscan born of Tuscans, [but] do not regret abandoning Volsinii’s hearths in battle” (‘Elegies’ 4.2); and

✴Festus (‘De verborum significatu’, 228 Lindsay) recorded that Flaccus was portrayed in the temple of Vertumnus on the Aventine Hill, wearing the purple toga that signified his triumph of 264 BC.

As Giorgio Ferri (referenced below, at pp. 138-9) has pointed out, it is possible that Flaccus had “called” Voltumna to Rome in the ritual known as evocatio deorum. The aftermath of the fall of Veii in 396 BC would have provided a precedent:

✴ In his account of the closing stages of the final siege of Veii, Livy recorded that:

“... the dictator [Marcus Furius Camillus] ... vowed, according to a decree of the Senate, that he would celebrate the great games on the capture of Veii, and that he would repair and dedicate the temple of Mother Matuta, which had been formerly consecrated by King Servius Tullius”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 19: 6).

In his prayers before the final assault, Camillus included the following:

“Queen Juno, who inhabits Veii [and whom the Etruscans worshipped as Uni], I beseech you to accompany us, when we are victors, into our city [i.e. to Rome], soon to be thine, where a temple worthy of your majesty shall receive you”, (‘History of Rome’, 5: 21: 3).

The city of Veii duly fell:

“When all human wealth had been carried away from Veii, [the Romans] began to remove the offerings to their gods and the gods themselves, but more after the manner of worshippers than of plunderers. For youths selected from the entire army, to whom the charge of conveying queen Juno to Rome was assigned, after having thoroughly washed their bodies and arrayed themselves in white garments, entered her temple with profound adoration, applying their hands at first with religious awe, because, according to the Etruscan usage, none but a priest of a certain family had been accustomed to touch that statue. Then when someone ... asked, ‘Juno, art thou willing to go to Rome?’ the rest joined in, shouting that the goddess had nodded assent. To the story an addition was afterwards made, that her voice was heard, declaring that ‘she was willing’. Certain it is .. that, having been raised from her place by machines of trifling power, she was light and easily removed ... [and] safely conveyed to the Aventine Hill, her eternal seat, whither the vows of the dictator had invited her; where the same Camillus who had vowed it, afterwards dedicated a temple to her, [the Temple of Juno Regina], (‘History of Rome’, 5: 22: 3-8).

✴Dionysius of Halicarnassus gave an almost identical account:

“This same Camillus, when conducting his campaign against Veii, made a vow to Queen Juno of the Veientes that if he should take the city he would set up her statue in Rome and establish costly rites in her honour. Upon the capture of the city, accordingly, he sent the most distinguished of the knights to remove the statue from its pedestal; and when those who had been sent came into the temple and one of them ... asked whether the goddess wished to remove to Rome, the statue answered in a loud voice that she did. This happened twice; for the young men, doubting whether it was the statue that had spoken, asked the same question again and heard the same reply” (‘Roman Antiquities’, 13: 3).

On this precedent, Voltumna would have willingly abandoned Volsinii’s hearths (as Propertius recalled) and taken residence in Flaccus’ temple on the Aventine. The ritual would have graphically underlined the demise of the Etruscan League, over which Voltumna had previously presided.

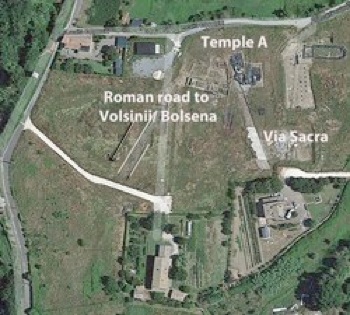

Campo della Fiera

Orvieto, with the excavated sanctuary at Aerial view of the excavated site at

Campo della Fiera in the foreground Campo della Fiera

A candidate for the site of the fanum Voltumnae emerged in 1876, when archeologists first discovered signs of important ancient cult site at Campo della Fiera, on the plain below Orvieto. The extensive excavations that have been carried out on this site in recent years have revealed that the sanctuary contained at least four temples, three of which seem to have been destroyed in the late 4th or early 3rd century BC: Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2013, at p.651) suggested that this occurred in the period from 308 BC, when Decimus Mus first attacked the city, until 280 BC, when it finally fell to Rome. She commented:

“The clashes with Rome cannot have left the sanctuary unscathed: what seems certain is that neither in Temple B nor Temple C did the cult continue to function into Roman times [i.e. after 264 BC, when] worship was reserved for Temple A, where the temenos wall was restored several times.”

A number of scholars agree with Giovanni Colonna (referenced below, at p. 204) that:

“...we might reasonably assume, albeit that definitive proof is lacking, that [the sanctuary of the Etruscan League at the fanum Voltumnae] can be identified as the sanctuary .... at Campo della Fiera” (my translation).

Lammert Bouke van der Meer (referenced below, at p. 105) accepted that this was probable, but he cautioned that:

“... we cannot be sure until an inscription mentioning Veltumne or Veltune [the Etruscan names for the deity to which the fanum Voltumnae was presumably dedicated] is found ....”

In fact, the name of one of the deities worshipped here was scratched on the inside of the base of a bucchero cup (ca. 400 BC) according to Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2013, at p. 636) it was found near the tufa altar in the sacred area of Temple A. This graffiti read: “apas” (of the father), the counterpart of the another inscription, “atial” (of the mother) found near Temple C (below).. This graffiti read: “apas” (of the father), the counterpart of the another inscription, “atial” (of the mother) found near Temple C. Claudia Giontella (referenced below, 2011, at p. 291) observed that:

“... [the word] “apas” (of the father) probably indicates ownership by the father par excellence, Tinia, to be identified with ... Voltumna deus Etruriae princeps [(Voltumna, the principal god of the Etruscans)]” (my translation).

In other words, this cup could have been offered to Tinia Velthumna, the god known to Livy as Voltumna.

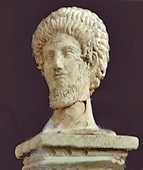

Bust of a divinity from Campo della Fiera Comparison with Veltune

Museo Archeologico, Orvieto S. Stopponi (ref. below, 2014, Fig. 33)

It is also important to note that there might be relevant evidence from the terracotta bust illustrated above, which was found under the tufa altar in the sacred area of Temple A when the altar itself was removed for restoration (as described by Simonetta Stopponi at the end of this videoclip). The bust had been carefully buried there so that it looked up at the altar (as illustrated in the photograph above, on the left, which was taken from above, after the altar had been removed, but while the bust was exposed but still in situ). Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2014, at p. 85) dated it to ca. 400 BC. She argued that this was the head of a god, as evidenced by its similarities with a bust (ca. 350 BC) of Hades from Morgantina in Sicily, which was recently returned to Sicily by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu. She tentatively suggested (at p. 86 and at Figure 33, reproduced above) that the bust from Campo della Fiera might depict Veltune, as evidenced by its similarities to the head of figure of this god on the mirror from Tuscania described above. It is tempting to think that the statue had been ritually buried under the altar here in 264 BC so that Flaccus could not send it to Rome.

None of this constitutes the kind of definitive proof that Lammert Bouke van der Meer (above), for example, was looking for. Nevertheless, the circumstantial evidence for the proposition that the fanum Voltumnae was at Campo della Fiera is arguably compelling.

Rite of the Clavus Annalis

As discussed below, according to Livy:

“Cincius, a careful writer on [ancient monuments], asserts that there were seen at Volsinii ... nails fixed in the temple of Nortia, an Etruscan goddess, as indices of the number of years”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 7).

This passage formed part of Livy’s account of the ancient rite of the clavus annalis at Rome, which is discussed further below. In the opinion of Henk Versnel (referenced below, at p. 276):

“... it seems only natural that the clavus annalis was fixed during the [annual meetings of the Etruscan League at the fanum Voltumnae] ...”

The sections below explore the analysis that underlies Versnel’s important suggestion.

Rite of the Clavus Annalis at Rome

The Livian passage quoted above formed part of a digression on the ancient rite of the annual ‘hammering in of the nail’:

“There is an ancient law, written in archaic letters, that reads: ‘Let him who is the praetor maximus [the original name of chief magistrates of the Republic] fasten a nail on the Ides of September’. This notice was fastened up on the right side of the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, next to the ‘temple’ of Minerva. This nail is said to have marked the number of the year (written records being scarce in those days) and was, for that reason, placed under the protection of Minerva because she was the inventor of numbers”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 5-7).

This is consistent with the definition of Verrius Flaccus, epitomised by Festus :

“The ‘clavus annalis’ [annual nail] was so called because it was fixed into the walls of the [Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in Rome] every year, so that the number of years could be reckoned ...” (‘De verborum significatu’, 49 Lindsay).

Livy explained:

“The consul Horatius established the [ancient] law and dedicated the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in the year following the expulsion of the kings”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 8).

Henk Versnel (referenced below, at p. 270 ) pointed out that the rite of the clavus annalis was carried out on:

“... the dies natalis [anniversary of the day of dedication] of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, [which was also] the day regarded as the beginning of the Roman Republic, since, according to tradition, M. Horatius, one of the [five men traditionally named as consuls during] the first year after the expulsion of Tarquin [the last Etruscan king of Rome], had dedicated the temple [on this day in 509 BC].”

In other words, the annual hammering in of the nail at the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus had once provided a measure of the number of years that had passed since the start of the Republic.

As we have seen, Livy noted that:

“Cincius, ... asserts that, at Volsinii , nails were fastened in the temple of Nortia, an Etruscan goddess, to indicate the number of the year”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 7-8)

Thus, it is possible that the ancient annual rite had been brought to Rome by the Etruscans. Stephen Oakley (referenced below , 1998, at p. 81 observed that this ‘Cincius’ is almost certainly the antiquarian Lucius Cincius, and that the source is probably the ‘mystagogicon’, which he probably wrote prior to the burning of capitol in 83 BC. He also argued (at p.75) that the information above from both Livy and Festus derived from the same passage of Cincius. The important point is that, according to all of these sources, the annual hammering of the nail in the ancient past, at Volsinii and (from 509 BC) at Rome, had served the purpose of marking the passage of the years.

Francisco Pina Polo (referenced below, at p. 39) observed that:

“Livy understood [the one-off appointment of the dictator clavi figendi causa of 363 BC to be] an attempt at recovering a lost [and previously annual] rite. Perhaps this was indeed the case and, maybe, the clavus annalis had ceased to exist, at least from the beginning of the 4th century BC. However, this could [alternatively] be a case of incorrect interpretation on the part of Livy, who may have [believed incorrectly] that the [occasional] appointment of a dictator specifically for fixing the nail [for expiatory purposes] meant that the annual ritual [for the continual recording of time] had ceased to exist.”

Unfortunately, we have no basis upon which to decide between these alternatives and, if Livy had made a mistake, we have no way of knowing when the annual rite was actually abandoned in Rome. It is, however, clear that it had been abandoned by the time that Livy was writing, since:

✴he was reliant on Cincius’ record of the archaic inscription in the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus; and

✴he seems to have written his account for an audience that had never come across it. However, a few years earlier, Cicero had begun a letter to Aiiicus as follows:

“I arrived at Laodicea on the 31st of July [51 BC]. From this day, ex hoc die clavum anni movebis (you should move the nail of the year”, (my translation of ‘Letter to Atticus’, 5:15)”.

Here, Cicero suggested that Atticus should measure the year of his (i.e. Cicero’s) stay in Laodicea in the ancient manner. The casual nature of this suggestion indicates that the rite of the clavus annalis was still recalled, at least in some quarters at this time.

Rite of the Clavus Annalis at Volsinii

Remains of the so-called Tempio del Belvedere (ca. 500 BC) at Orvieto

We can now return to Livy’s assertion that, according to Cincius:

“... there were seen at Volsinii ... nails fixed in the temple of Nortia, an Etruscan goddess, to indicate the number of years”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 7).

Since Livy included Cincius’ account within his own account of the practice at Rome in the early Republic, it would be natural to assume that Cincius was referring to Volsinii before its destruction in 264 BC. Henk Versnel (referenced below, at pp. 273-4) was clearly of this opinion: referring to Livy’s summary of Cincius’ information, he asserted that:

“This is a highly significant statement. We learn from it that the clavi fixatio, like most of the rites around the idus septembres [at the the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus], was an Etruscan usage, associated with the goddess Nortia and taking place in or near Volsinii.”

As noted above, Volsinii was almost certainly on the later site of Orvieto before it was destroyed in 264 BC. There is evidence there for two ancient temples there at which a goddess akin to the Greek Athena (whom the Romans had absorbed as Minerva) was venerated:

✴According to Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2003, at p. 247), fragments of a frieze (ca. 500 BC) from the temple in Vigna Grande that are preserved [in museums ??] at Orvieto and Toronto came from a relief that:

“... [depicted] the Gigantomachy of Athena [the mythical battle in which the Athena defeated the giant Enceladus] and probably related to the dedication of the temple” (my translation).

These temples were close together on the northeast edge of the cliff, probably outside the urban centre of the Etruscan city.

As Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, 2017, at note 37) pointed out, we have no hard evidence to confirm that this deity was explicitly identified as Nortia at either temple. However, Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2003, at p. 257) suggested that the votive bronze from the Tempio del Belvedere represented a goddess of fate who was associated with:

“... the tradition [derived from Cincius] that attributes to Volsinii the ceremony of the clavus annalis ... at the temple of Nortia, [which was] repeated at Rome in the cella of Minerva at the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus; the goddess at the Tempio del Belvedere could therefore be a ‘Minerva Nortina’ ...” (my translation).

The tri-partite structure of the Tempio del Belvedere and the fact that its dedication seems to have been to Tinia/ Jupiter are certainly obvious parallels of the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in Rome: we can reasonably assume that Tinia shared this temple with the Etruscan goddesses Uni (Roman Juno) and Nortia (Roman Minerva).

Simonetta Stopponi suggested that:

“It is ... probable that the cult of Minerva, in her various aspects, had its [main Volsinian] seat at the temple at Vigna Grande, where the deity was portrayed in battle with the giants [as mentioned above]” (my translation).

However, it seems to me that, if Cincius was indeed describing the situation at Volsinii before 264 BC, his Volsinian “temple of Nortia” in which the rite of the clavus annalis took place would probably have been the cella of the goddess in the tripartite Tempio del Belvedere.

Rite of the Clavus Annalis at Campo della Fiera ?

Satellite view showing the route from the Tempio del Belvedere at Volsinii/ Orvieto

to the nearby sanctuary at Campo della Fiera

It is now time to return to the opinion of Henk Versnel (referenced below, at p. 276), that:

“... it seems only natural that the clavus annalis was fixed during the [annual meetings of the Etruscan League at the fanum Voltumnae] ...”

He began his reasoning (at pp. 272-3) by pointing out that, in Rome:

“On [the ides of September]:

-the magistrates of the initial period of the Republic entered into their office;

-the day was taken as the dies natalis of the state god Jupiter; [and]

-the clavus annalis was driven into the wall of the cella of Minerva [in the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus].

There is no room for any doubt: for some time in the [early] Republic, the idus septembres were taken as the calendrical New Year’s Day, and the celebration of this day took place in [the form of] a New Year Festival of the type ... [known to have take place in] Egypt, Mesopotamia and other Near Eastern countries ...”

He suggested (at p. 273) that these rites had reached Rome via Etruria:

“When, immediately after the regal period, the Roman magistrate entered upon his office on September 13th in a ceremony attended by games [the ludi Romani], ... this procedure was not [newly-invented], but was taken over from the period of the kings, notably the Etruscan kings. It is probable, therefore that the investiture of this magistrate on the idus septembres goes back to an Etruscan ritual.”

He continued by asserting that:

“The usage of the ‘clavus annalis’ as part of these rites [at Rome] ... will be found to settle this issue [i.e. that the celebration at Rome was a New Year festival of Etruscan origin].”

To justify this assertion, he turned to Cincius’ information that the rite of the ‘clavus annalis’ was celebrated at Volsinii. He asked rhetorically (at pp. 274-5):

“Was the clavi fixatio at Volsinii part of a more comprehensive annual ceremony? I think that this can indeed be made plausible. In or near Volsinii, another very important politico-religious ceremony took place: the annual meetings of the Etruscan League.”

He concluded (at p. 276) that:

“... we [thus] find a number of ceremonies at Volsinii [i.e. the clavus annalis at Volsinii itself and the annual meetings of the Etruscan League at the nearby fanum Voltumnae] uniting into a whole ... that so closely corresponds to the rites around the idus septembres at Rome that coincidence is out of the question:

✴in both instances [i.e. at Rome and at Volsinii], we see the clavi fixatio, one of the best arguments for the theory that the ceremonies bore the character of a New Year ritual;

✴in both instances, a leading functionary enters into his one-year period of office; and

✴in both instances, this magistrate is the leader of the annual games that form the religious centre of the complex [i.e. ritual ??].

On this basis, he suggested that the ides of September (i.e. the autumnal equinox) might have been the first day of the Etruscan year.

As far as I can see, Versnel offered only the circumstantial evidence (in the form of the geographical proximity of two important annual festivals) for his claim that the rite of the clavus annalis at Volsinii was part of the ritual at the the annual meeting of the Etruscan League at the fanum Voltumnae: Cincius himself had apparently not made this connection. However, Francesco Roncalli (referenced below, p 225-7) pursued this line of enquiry from a different direction. He started with the following observation:

“Each of the Etruscan cities must have had its own place where the passing years ... was officially registered and ritually sanctioned. It seems significant that only the tradition at Volsinii and the custodian of the rite there, Nortia, whom Livy promoted to the rank of ‘Etruscan goddess, achieved fame in this context in the Roman world” (my translation).

“... the goddess Nortia, ... it seems, was worshipped only at Volsinii ...”

We know of at least one other example of the rite in which it was associated with neither Nortia nor Volsinii: Nancy Thomson de Grummond (referenced below, at pp. 52-3) pointed out that the naked goddess who drives the nail in the relief on this mirror (ca. 320 BC) from Perugia (now in the Antikenmuseum, Berlin) is identified by inscription as ‘Athrpa’:

“... a name coming from ‘Atropos’, [a] Greek goddess of fate.”

Her vocation as a goddess of fate was underlined in the mirror by placing her between two pairs of lovers who were about to be separated by death. We might reasonably assume that the Perugians used the name ‘Athrpa’ for the goddess who presided over the rite of the clavus annalis there.

If the rite was widely celebrated in Etruria, we must return to the question that Roncalli prompted us to ask: why did Cincius single out the practice at Volsinii and why did Livy (perhaps following Cincius) promote the very ‘Volsinian’ Nortia to the rank of an ‘Etruscan goddess’? Roncalli himself made two related suggestions:

-“Perhaps this was because the recording of time at Velzna [i.e. at Volsinii before 264 BC] had pan-Etruscan relevance, possibly because it recorded, among other things, the annual pan-Etruscan councils?

-Perhaps the role of the priest who was elected by the ‘twelve people’ to preside over these annual councils was analogous to that of the “praetor maximus”at Rome, who - probably following the Etruscan tradition - drove the nail in the cella of Minerva, thereby entrusting ‘his’ year, its collegiate discussions and his own authority, to the inscrutable immutability of destiny ?” (my translation).

Again, this is not hard evidence: as discussed below, Cincius could have had other reasons than these.

If Versnel and Roncalli were correct, and Cincius was describing part of the rite that attended the annual federal meetings at the fanum Voltumnae before 264 BC, we must assume that:

✴the rite was celebrated at an (as-yet unidentified) temple of Nortia at the fanum Voltumnae; or

✴this part of the annual federal meeting took place in Volsinii. (I have illustrated above the route from the Tempio del Belvedere to Campo della Fiera via the Strada Fontana del Leone and the Strada dell’ Arcone, which might have provided a reasonably convenient (i.e. not too steep!) ‘ritual link’ of some 3 km between the two locations.)

Either of these scenarios is possible.

However, there is still the conundrum of Cincius: if he was describing a rite that took place at the federal sanctuary, one wonders why he did not say so (particularly since Nortia was closely associated with Volsinii, but was not, as far as we know, with the Etruscans more generally). We only have Livy’s précis but, had Cincius provided this additional information, Livy would surely have seized on it to explain what he clearly considered to be an opaque situation in Rome. I suggest below that Cincius might alternatively have described the situation at the ‘new’ Volsinii after 264 BC: this city was, after all, renowned as the city of Nortia (still in her Etruscan form) well into the 4th century AD. Perhaps Cincius’ account reflected the fact that the rite also survived there long after it had been abandoned elsewhere ??

If I am correct, this does not rule out the idea that the rite had been celebrated at the fanum Voltumnae; it simply means that Cincius’ account cannot necessarily be taken as evidence that it was. I think that the circumstantial evidence adduced by (inter alia) Henk Versnel, Francesco Roncalli and Simonetta Stopponi (above) remains compelling. In my view, the most likely scenario prior to 264 BC is that the newly-elected sacerdos at each year’s meeting at the fanum Voltumnae travelled in a ritual procession to what is now called the Tempio del Belvedere, where he drove a nail to mark the start of his year of office.

Nortia and the Clavus Annalis After 264 BC

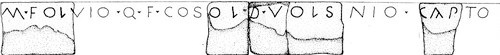

Inscription (CIL I 2836) from one of two statue bases from the

Sanctuary of Mater Matuta and Fortuna Virilis, Rome

[Now in the Musei Capitolini, Rome ??].

Drawing in M. Torelli (1968), referenced below

Pliny the Elder recorded that:

“... Metrodorus of Scepsis, who had his surname from his hatred of the [Romans], reproached us [i.e. the Romans] for having pillaged the city of Volsinii for the sake of the 2,000 statues that it contained” (‘Natural History’, 34:16).

The figure of 2,000 is likely to have been an exaggeration. Nevertheless, Flaccus must have taken a large number of cult statues to Rome (in addition to that of Voltumna).

Some of these statues seem to have represented Nortia, as evidenced by three donaria (votive altars) that were found in 1961 on the site of the sanctuary of Mater Matuta and Fortuna Virilis (later Sant’ Omobono) in Rome. These comprised

✴a large circular altar with holes that would have accommodated statues of some 3 feet high; and

✴two flanking rectangular altars with holes that would have accommodated statues of some 2 feet high, both of which carried the following inscription (CIL I 2836):

M FOLV[IO Q F COS]OL D VOLSI[NIO CAP]TO

M Fulvius, son of Quintus, consul, dedicated [it] after Volsinii had been captured

Katherine Welch (referenced below, at p. 502) described the evolution of this site:

“One of the kings [of Rome] ... had built a temple here ... Shortly after the founding of the Republic, this temple seems to have been intentionally demolished and covered with a massive earthen deposit, presumably as a symbolic gesture commemorating the expulsion of the kings. A platform of tufa was later constructed over it, probably by Furius Camillus, who won Rome’s first victory over the Etruscans at Veii, in 396 BC. Two temples were built upon the platform:

-one commissioned by Camillus [himself, which housed the statue of Juno that Camillus had ritually ‘called’ from Veii]; and

-the other [commissioned] by Fulvius Flaccus, who defeated Volsinii in 264 BC. Flaccus’ temple precinct is notable for its display of scores of looted bronze statues, only 3 feet high (a common statuary size at the time).

These temples, dedicated to Mater Matuta and Fortuna respectively, continued to adhere to traditional Etrusco-Italic architectural forms.”

Since Flaccus’ donaria were in the precinct of the Temple of Fortuna, and since Fortuna (like Minerva) was a Roman deity akin to Nortia, we may reasonably assume that some or all of the statues that they displayed were of Nortia , and that these were votive statues that Flaccus had looted from the temple in Vigna Grande and/or or the Tempio del Belvedere at Volsinii.

Temple A Rededicated to Nortia?

Donative altar (ca. 264 BC), in the sacred area in front of Temple A

Much of the sanctuary at Campo della Fiera was probably destroyed at in the havoc of 264 AD. However, as noted above, the area around Temple A remained in cult use. This is evidenced, for example, by the donarium (illustrated above) that has been excavated in the sacred area in front of this temple, which was closely aligned with the temple itself. According to Alba Frascarelli (referenced below, at p 141):

“Definitely, in view of the fact that the Sant’ Omobono altars [above] provide a close comparison for the mouldings of [the donarium at Campo della Fiera], it can be concluded that there is a narrow and precise correspondence between [all four altars], such as to allow us to hypothesis not only the same chronology but also a shared [programme of] planning and commissioning” (my translation).

In other words, Frascarelli suggested that Flaccus had commissioned all four of these donative altars after his triumph.

One wonders what exactly Flaccus donated to the temple at Volsinii, which he had probably just despoiled?? The upper surface of the altar here, like those of his altars at Rome, was equipped with holes that probably accommodated bronze votive offerings (albeit those at Volsinii would have been significantly smaller). I suggest that:

✴Flaccus commissioned the donarium at Campo della Fiera for other votive statues of Nortia that he had taken from Velzna (and/or possibly from a temple of Nortia elsewhere in the sanctuary that has yet to be identified); and

✴these statues, which he donated to the now-empty Temple A, signified that it had been re-consecrated to Nortia.

[Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, 2017, at pp. 224-7) noted that:

“... Nortia, the goddess of fate who was closely linked to the ambient of Volsinii, according to [Mario] Torelli, would have received the legacy of Veltumna after the destruction of the [fanum Voltumnae]” (my translation).

I have not yet tracked down the relevant paper by Mario Torelli. ]

I suggest below that Flaccus rededicated this temple in reaction to the Carthaginian invasion of Sicily in 264 BC, in order placate Nortia, the goddess of fate: he had, after all, just destroyed her temples at Volsinii and, without a suitable placatory intervention, she the might have rushed to the aid of the Carthaginian invaders in order to extract her revenge.

Extra-urban Temple of Nortia at Campo della Fiera?

Excavated site at Campo della Fiera

We might also wonder about the status of Temple A, now the putative temple of Nortia: as noted above:

-the fanum Voltumnae had probably lost any vestige of its federal character by this time and much of it was no longer in cult use; and

-the old city of Volsinii had been razed to the ground.

The obvious scenario is that this temple now served as an extra-urban sanctuary for the resettled people at Volsinii/ Bolsena.

The aerial view above shows the remains of paved road that ran southwest from this temple (picked out by two parallel white lines): according to Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2013, at p. 633) this road:

“... was built in the mid 3rd century BC. The track, [which is now] exposed for more than 50 meters, was five meters wide and furrowed by the passage of wagons, connecting Orvieto with Bolsena.”

This road must have constituted an ‘umbilical cord’ some 10 km long, linking the displaced people on the shores of Lake Bolsena to what remained of their ancient city and ancient religion.

If Temple A had indeed been re-dedicated to Nortia, this nostalgia would explain why she continued to be venerated in her Etruscan form well into the 4th century AD, not only at Volsinii but also by Volsinians who had moved to Rome.

Rite of the Clavus Annalis at the Rededicated Temple A ?

Bronze nails from Campo della Fiera, now in the Museo Archeologico, Orvieto

Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2013, at p. 635) reported the discovery of a number of bronze nails, some of which appeared to have been unused, along the southern wall of Temple A and gave the following assessment of their significance:

“The most likely interpretation of the nails is for architectural terracottas, but the presence of such a large number of specimens raises the appeal to the Volsinian tradition of the clavus annalis, which was [originally] affixed to the temple of the goddess Nortia, recognised by some in the Orvietan Belvedere temple.”

I would like to suggest that these nails might be associated with the transfer of the rite of the clavus annalis from the Tempio del Belvedere to Temple A after the former had been destroyed in ca. 264 BC and the latter had been rededicated to Nortia.

We might note in this context that the last-known appointment in Rome of a ‘dictator clavi figendi causa’ (a dictator appointed to fix the nail) occurred at about this time: as noted above, Cn. Fulvius Maximus Centumalus was appointed to this post in 263 BC, just after the outbreak of the First Punic War. Scholars seem to be at a loss to explain this appointment:

✴Francisco Pina Polo (referenced below, at p. 38) pointed out that the three other such appointments of which we have a record (in 363, 331 and 313 BC) had all been for specific for expiatory purposes, before observing that:

“... the fasti allude, for the year 263 BC, to Cn. Fulvius Maximus Centumalus as dictator clavi figendi causa, without, however making any reference to the reason for such an appointment.”

✴John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 17) simply said:

“The dictatorship [in all its forms] was, by its nature, an irregular office and often the duties [associated with it] were quite trivial, [albeit that] the appointment was a high honour. Cn. Fulvius Maximus Centumalus, for example, was appointed in 263 BC to carry out the religious ceremony of the ‘banging of the nail’ (clavi figendi causa) ...”

It seems to me that the appointment in 263 BC was not trivial: like the commissioning of the donative altars at both Rome and Volsinii, it was probably deemed necessary in order to placate Nortia, the goddess of fate, whose temples at Volsinii had just been destroyed, and who might otherwise have rushed to the aid of the Carthaginian invaders. Perhaps the introduction of the rite of the clavus annalis at Temple A also formed part of this placatory programme?

Was Cincius Describing the Situation at Volsinii after 264 BC?

We can now return for the last time to Livy’s assertion that, according to Cincius:

“Cincius, a careful writer on such [inscriptions or monuments], asserts that there were seen at Volsinii also nails fixed in the temple of Nortia, an Etruscan goddess, as indices of the number of years”, (‘History of Rome’, 7: 3: 7).

As discussed above, I doubt (pace Henk Versnel and Francesco Roncalli) that Cincius was describing a rite that took place before 264 BC as part of the annual federal meetings at the fanum Voltumnae. Rather, I would like to suggest that he was describing the rite at the extra-urban sanctuary of Volsinii/ Bolsena thereafter.

To pursue this line of enquiry, we need to think about Cincius himself. Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 114) suggested that the nomen of the Cincii was Etruscan, which might explain his knowledge of the ritual practices at Volsinii. Unfortunately, his identity, and thus the time at which he was writing, are both problematic:

✴Jacques Heurgon (referenced below) suggested that he was the antiquarian Cincius who was Livy’s contemporary.

✴Gary Forsythe (referenced below, at p. 62, note 20), who did not accept Heurgon's arguments, alternatively identified him as L. Cincius Alimentus, the historian who had written in Greek in the late 3rd century BC.

✴For Timothy Cornell and Edward Bispham (in T. J. Cornell (Ed), referenced below, I:183), Jacques Heurgon had proved that Cincius was the antiquarian who was broadly a contemporary of Livy:

“... beyond all reasonable doubt.”

Given this difference of view, we must consider both of these possibilities:

✴If Cincius and Livy were broadly contemporaries, then Livy would have had a good idea of the historical framework within which Cincius was writing: the fact that he quoted Cincius to illuminate his own account of the situation at Rome in the early Republic implies that he knew (or could assume with confidence) that Cincius was referring to the situation at Volsinii as it had existed before 264 BC.

✴However, if Cincius had written his account in the late 3rd century BC, he could have been describing the situation in or shortly before his own time, when Volsinii would have been the city on Lake Bolsena. Livy might have included his account: because he assumed (perhaps incorrectly) that it related to the time of the early republic.

There is, of course a third possibility: it might have been clear to Livy that Cincius (whenever he wrote his account) described the situation at Volsinii/ Bolsena after 264 BC: Livy might have quoted him simply because this was the oldest evidence that he could find to support the information contained in the archaic inscription from the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. In short, this digression as to the identity of Cincius takes us no further in elucidating the precise significance of his account.

For what it it is worth, I think that Cincius described the rite at the Campo della Fiera after 264 BC:

✴In answer to Francesco Roncalli’s rhetorical questions (above), I think that he:

•probably focussed on the situation at Volsinii because the rite of the clavus annalis continued there (we know not for how long) after it had ceased to be celebrated elsewhere; and

•probably ‘promoted’ Nortia, its presiding deity, to the status of an Etruscan goddess because the Volsinians preserved her Etruscan identity long after most other Etruscan cults had been Romanised or simply abandoned.

✴This does not rule out the possibility that the rite had its roots in the annual festival at the fanum Voltumnae. Again, for what it is worth, I think that this was probably the case. However, had Cincius been referring to this ancient pan-Etruscan celebration, I think that he would have said so.

Read more:

Ricci M., “Praetores Etruriae XV Populorum: Revisione e Aggiunte all’ Opera di Bernard Liou”, Bollettino della Deputazione di Storia Patria per l’Umbria, 111:1 (2014) 5-30

Cornell T. J. (editor), “The Fragments of the Roman Historians” (2013) Oxford

Colonna G., “I Santuari Comunitari e il Culto delle Divinità Catactonie in Etruria”, in:

della Fina G. (editor, “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, Annali della Fondazione per il Museo ‘Claudio Faina’, 19 (2012) 203-26

Ferri G., “Tutela Urbis: Il Significato e la Concezione della Divinità Tutelare Cittadina nella Religione Romana”, (2010) Stuttgart

Thomson de Grummond N. T., “Prophets and Priests”, in:

dhomson de Grummond N. T. and Simon E. (editors), “Religion of the Etruscans”, (2006) Austin, Texas, pp. 27-44

Roncalli F., “I Culti’, in:

della Fina G. and Pellegrini E. (editors), “Storia di Orvieto: Antichità”, (2003) Perugia, pp 217-34

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume II: Books VII and VIII”, (1998) Oxford

Oakley S., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume I: Book VI”, (1997) Oxford

Cornell T. C., “The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (ca. 1000-264 BC)”, (1995) London and New York

Gros P., “Bolsena I: Scavi della Scuola Francese di Roma a Bolsena (Poggio Moscini): Guida agli Scavi”, Mélanges d' Archéologie et d' Histoire, 6 (1981)

Versnel H. S., “Triumphus: An Inquiry Into the Origin, Development and Meaning of the Roman Triumph”, (1970) Leiden

Capdeville G., “Voltumna ed altri Culti del Territorio Volsiniese, in:

“Volsinii e il suo Territorio”, Annali della Fondazione per il Museo ‘Claudio Faina’, 6 (1999) 109-36

Harris W., “Via Cassia and the Via Traiana Nova between Bolsena and Chiusi”, Papers of the British School at Rome, 33 (1965) 113-33

Pallottino M., “Uno Specchio di Tuscania e la Leggenda Etrusca di Tarchon”, Rendiconti dell’ Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 6 (1930) 49-87

Dennis G., “Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria”, (1848) London

Müller K., “Die Etrusker” (1828) Breslau

Niebuhr G. B., “Roman History” (1827) London

Zuddas E., “La Praetura Etruriae Tardoantica”, in:

Cecconi G. A. et al. (editors), “Epigrafia e Società dell’ Etruria Romana (Firenze, 23- 24 ottobre 2015)”, (2017) Rome

Stopponi D., “Un Santuario e i suoi Artisti”, Annali della Fondazione per il Museo ‘Claudio Faina’, 21 (2014) 75-98

Stopponi S., “Orvieto, Campo della Fiera: Fanum Voltumnae”, in:

Macintosh Turfa J. (editor), “The Etruscan World”, (2013 ) Oxford, Chapter 31

Bouke van der Meer L., “Campo della Fiera at Orvieto and Fanum Voltumnae: Identical Places ?”, BABESCH, 88 (2013) 99-108

Frascarelli A., “Un Donario Monumentale a Campo della Fiera”, in:

della Fina G. (editor, “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, Annali della Fondazione per il Museo ‘Claudio Faina’, 19 (2012) 131-60

Giontella C., “Lo Scavo Archeologico di Campo della Fiera ad Orvieto”, Il Capitale Culturale, 2 (2011) 285-98

Pina Polo F., “The Consul at Rome: The Civil Functions of the Consuls in the Roman Republic”, (2011) Cambridge

Welch K., “Art and Architecture in the Roman Republic”, in:

Rosenstein N. and Morstein-Marx R. (editors), “A Companion to the Roman Republic”, (2007) Oxford, pp 496-542

Stopponi S., “I Templi e l’ Architettura Templare”, in:

della Fina G. and Pellegrini E. (editors), “Storia di Orvieto: Antichità”, (2003) Perugia, pp 235-74

Forsythe G., “Livy and Early Rome: A Study in Historical Method and Judgment”, (1999) Stuttgart

Lazenby J., “The First Punic War”, (1996) Abingdon

Torelli M., “Il Donario di M. Fulvio Flacco nell' Area di Sant’ Omobono”, Quaderni dell'Istituto di Topografia Antica della Università di Roma, 5 (1968 ) 71-6

Heurgon J., “L. Cincius et la Loi du Clavus Annalis”, Athenaeum, 42 (1964) 432-7

Syme R., “Senators, Tribes and Towns”, Historia: Zeitschrift fur Alte Geschichte, 13:1 (1964) 105-25

Return to Conquest of Italy (509 - 241 BC)