Fragment of a relief (early 1st century AD) depicting personifications of Vetulonia, Vulci and Tarquinii

From Caere, now in the Museo Gregoriano Profano, Musei Vaticani, Rome

Image of a plaster cast: the original is illustrated at p. 22 of “Cerveteri et les Étrusques, une Cité d’Italie avant Rome”

According to Paolo Liverani and Paola Santoro (referenced below, at p. 325) the relief illustrated above, which was found in 1840-6, during the excavation of the site of the Roman theatre of the Etruscan city of Caere (modern Cerveteri), was:

-

“... once perceived as a fragment of a throne, [the so-called Throne of Claudius], but it was actually from one of the sides of an altar of the Claudian era [41-54 AD]. On it were carved personifications of the people of three Etruscan cities: [from left to right], Vetulonia, Vulci and Tarquinii”, (my translation).

These figures are identified by inscriptions (CIL XI 3609):

Vetulonenses V[ol]centani Tarquinienses.

Liveroni and Santoro observed (at p. 326) that:

-

“This is only a fragment: the complete [relief] must have included personifications of the 15 members of the Etruscan League. This institution, whose existence is attested from the archaic period, had a religious and sometimes a political function. It was revived in the Julio-Claudian period for commemorative purposes”, (my translation).

I will return below to the context in which this relief was found and its wider implications. However, I first discuss the other (mainly epigraphic) evidence for the revival of this archaic institution.

Etruscan Federation (431 - 264 BC)

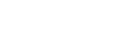

Orvieto, with the excavated sanctuary at Aerial view of the excavated site at

Campo della Fiera in the foreground Campo della Fiera

As described in my page Etruscan Federation and Fanum Voltumnae (431 - 389 BC), most of what we know about the original federation comes from Livy’s accounts of relations between Etruria and Rome in the period 434-389 BC and, in particular, from his account of the Romans’ 10 year siege of Veii (which culminated in the fall of that city in 396 BC). Livy recorded the meeting place of the federation as the fanum Voltumnae, which (according to Propertius, see below) seems to have been located near Volsinii (modern Orvieto). Marco Ricci (referenced below, at pp. 16-7) observed that:

-

“The picture [of the federation itself] that emerges [from Livy’s accounts] is ... that of a confederation of city-states, born above all out of military necessity, essentially defensive but also sustained by deeper cultural values than those of a purely military alliance” (my translation).

As I pointed out in this linked page, it is generally assumed that the sanctuary that has been excavated at Campo della Fiera, below the modern city (as illustrates above), contains the site of this archaic pan-Etruscan sanctuary. After the fall of Veii, the other members of the federation successively succumbed to the power of Rome, in a process that ended in the fall of Volsinii in 280 BC. As Ricci (referenced below, at p. 17) observed:

-

“Given the purpose for which the federation had been formed, it could not, of course, have survived the incorporation of Etruria into the orbit of Rome. Thus, after the fall of Volsinii and its subsequent destruction in 264 BC, it seems likely that federal meetings were prohibited” (my translation).

Ricci referred here to the Romans’ destruction of Volsinii in 264 BC, after which they:

-

✴destroyed the ancient city on the impregnable rock of what is now Orvieto;

-

✴moved the surviving population to the much less defensible site of ‘Roman’ Volsinii on the shores of Lake Bolsena; and

-

✴transferred the cult of Voltumna, the presiding deity of the federal sanctuary, to Rome (see below).

Revived Federation

Epigraphic Evidence

An important paper by Bernard Liou (referenced below) drew attention to 17 surviving (or at least recorded) inscriptions that commemorated men who had held the post of “Praetor Etruriae (XV Populorum)” or, less commonly, “Aedilis Etruriae”. The most illustrious of the holders of this office (as far as we know) was the Emperor Hadrian (117-38 AD): Aelius Spartianus noted that, among other examples of Hadrian’s devotion to ancient Latin and Italic institutions:

-

“In Etruria, he held a praetorship while emperor”, (‘Life of the Emperor Hadrian’, 2:19).

As we shall see, most of the epigraphic evidence for this office comes from Etruria, and it is therefore generally agreed that it related to a revived Etruscan federation of 15 cities.

Liou (see his conclusions at p. 79) believed that all of the surviving inscriptions in his database post-dated Hadrian’s tenure in this office. However, Marco Ricci (referenced below, at pp. 7-13) recently added three inscriptions to Liou’s list and (inter alia) reviewed the dating of the others: importantly, he argued that eight of the men commemorated in his list (below) held the post prior Hadrian.

Julio-Claudian Period

The earlier part of Ricci’s list can be summarised as follows:

-

✴S. Valerius Proculus, known from two inscriptions from Vettona (Bettona), (CIL XI 7979 and AE 1996, 653b - see below):

-

pr(aetor) Etruriae

-

early 1st century AD;

-

✴[C. ?] Metellius, one of two men of this name commemorated on an inscription (CIL XI 2115), from Cortona:

-

[pr(aetor)] Etruriae

-

first half of the 1st century AD;

-

✴Aul. Vicirius (CIL XI 1806), from Saena (Siena):

-

[pr(aetoris)?] Etruriae

-

after 45 AD;

-

✴T. Egnatius Rufus (CIL XI 3257), from Caere:

-

aed(ili) Etrur(iae)

-

from the period ca. 40-70 AD;

-

✴L. Alfius Quietus (CIL XI 2116), from Clusium (Chiusi):

-

aed(ili) Etrur(iae)

-

from the period ca. 40-70 AD;

-

✴? Pomponianus ? (CIL XI 5170), from Clusium (Chiusi):

-

aed(ili) Et[̣ruriae - - -]

-

date uncertain, although the other known aediles (above) date to ca. 40-70 AD;

-

✴C. Betuus Cilo (CIL XI 1941), from Perusia (Perugia):

-

pr(aetori) E[tr]uriae xv populorum

-

late 1st century AD;

-

✴ anonymous (AE 1980, 0459), from Rusellae (Roselle):

-

pr(aetori) Etr[uriae - - -]

-

from the period ca. 80-150 AD.

Marco Ricci noted (at p. 18) that, on the basis of the career information contained in this group of inscriptions, the early praetores Etruriae seem to have been men who had followed municipal careers.

After Hadrian

The subsequent inscriptions in Ricci’s list commemorated:

-

✴P. Tullus Varro (CIL XI 3664), from Tarquinii:

-

praetori Etruriae

-

from the period ca. 130-50 AD;

-

✴[...] Vopiscus C. Arruntius Catellius Celer, son of Pompeius, of the Pomptina tribe (AE 1980 0426), from Volsinii (Bolsena):

-

pr(aetori) Etruriae

-

from the period 140-56 AD;

-

✴L. Venuleius Apronianus Octavius (CIL XI 1432), from Pisae (Pisa):

-

praetori Etruriae V (i.e he held the post on five occasions)

-

second half of the 1st century AD;

-

✴Q. Petronius Melior (CIL XIV 5345), from Ostia:

-

praetori Etrur(iae) xv populoruṃ [bis?], (the completion suggesting that he held the post on two occasions)

-

from the period 180-4 AD;

-

✴...cus Modestus Paulinus(CIL IX 3667), from Marruvium (which was in Samnium):

-

praetor[i] Aetrur(iae) xv popul[or(um)]

-

from the period 200-25 AD;

-

✴anonymous (CIL XI 2699), from Volsinii (Bolsena):

-

praet(ori) Etrur(iae) xv populor(um)

-

from the period 222-35 AD;

-

✴anonymous patron of a temple to Nortia (CIL XI 7287), from Volsinii (Bolsena):

-

praet(ori) Etruriae] xv populor(um),

-

impossible to date, but possibly the same person as in CIL XI 2699, above;

-

✴L. Tiberius Maefanas Basilius (CIL XI 2115, Last Statues of Antiquity: LSA 1623), from Clusium (Chiusi):

-

ex praetoribus xv pop(ulorum)

-

from the period 300-30 AD;

-

✴anonymous (CIL XI 5170), from Vettona (Bettona):

-

[- - - prae]tore Aetruriae xv p(o)p(ulorum);

-

from the mid 4th century AD;

-

✴anonymous (CIL XI 2114), from Clusium (Chiusi):

-

pra]et(ori) xv pop(ulorum),

-

impossible to date.

Marco Ricci (referenced above, at pp. 21-3) drew attention to the fact that Hadrian was followed in this office by men of higher social and professional standing than had previously been the case. Clearly, the office (and hence the revived federation) continued into the 4th century AD.

Overall Conclusions

The inscriptions in Ricci’s database yielded valuable information on the characteristics of the revived federation. For example:

-

✴the title “Praetor Etruriae XV Populorum” in some of the inscriptions indicates that the number of cities that belonged to the federation had increased from the traditional 12 to 15;

-

✴the database provides evidence for holders of the office from:

-

•nine Etruscan cities:

-

-Chiusi (4);

-

-Volsinii/ Bolsena (3);

-

-Caere (1);

-

-Cortona (1);

-

-Perugia (1);

-

-Pisa (1);

-

-Rusellae (1);

-

-Siena (1);

-

-Tarquinii (1);

-

•Bettona (3 inscriptions, two of which probably relate to the same individual), which was in Augustus’ 6th region (Umbria) but it had belonged to Etruscan Perusia until ca. 40 BC and had shared its Etruscan culture thereafter; and

-

•the non-Etruscan cities of Ostia (1) and Marruvium (1); and

-

✴ the fact that Q. Petronius Melior (CIL XIV 5345) apparently held the office on two occasions suggests that it was held for a specific period (presumably a year) at a time.

However, perhaps the most important conclusion relates to the probably dating of the earliest of these inscriptions, which obviously provides a terminus ante quem for the revival of the federation, as discussed in the following section.

Date of the Revival of the Federation

Bernard Liou (referenced below, at pp. 94-5) tended to the view that the revival of the federation had occurred under the auspices of the Emperor Claudius (41-54 AD). However, Marco Ricci argued (at p. 7 and note 15 and 18) that:

-

✴the first two inscriptions in his list dated to the period 1 - 30 AD, as reflected in the EDR database (see the CIL/AE links above); and

-

✴they commemorated the same man, whom he identified as:

-

•Sex(tus) Valerius Sex(ti) / f(ilius) Clu(stumina) Proculus, / pr(aetor) Etruriae/ iivir in CIL XI 7979; and

-

•Sex(to) Valerio Sex(ti) f(ilio) Clu(stumina) / Proculo, / iiviro, pontifici/ pr(aetori) Etruriae in AE 1996, 653b.

Liou, who had written prior to the discovery of the second of these inscriptions, had dated the first to the late 2nd century AD, but Ricci noted that it had had been found in the Ipogeo di Colle, Bettona, and that the dating of the hypogeum itself and the other objects found inside it (which included a ring with head of Augustus on its bezel) precluded this late dating.

Mario Torelli (referenced below, at p. 91) had already argued on other grounds that Liou had been:

-

“... prudently cautious [in dating the revival]: although he does not reject the hypothesis of an act of political restoration by Augustus, he seems to prefer ... Claudius. I find the Augustan hypothesis ... more suitable, [since]:

-

✴the Claudian reforms to which Liou turns to justify [his view] are generally of very limited significance and ... in direct association with the ceremonial of Rome; and

-

✴[in order to identify the emperor responsible for this revival, we should look for examples of] ... wide-ranging and deep intervention in local affairs ...

-

Unfortunately, these examples are absent for Claudius, while, in the Augustan age, they are abundant ... In Etruria alone, one could cite the foundation of the Municipium Augustum Veiens [in 2 BC], in addition to the instances cited by [Eugen Bormann, in 1887].”

Marco Ricci (at p. 17) agreed with Torelli that:

-

“It [must have been] Augustus who, in the context of his policy of the restoration of cults and the exaltation of the local traditions, fostered the rebirth of the ancient Etruscan league, although, of course, in a different form [from the original]. ... It is impossible to identify a certain date [for this revival], but it seems appropriate to focus on the early years of the Christian era, perhaps close to the date of the re-founding of the municipium of Veii [in 2 BC]” (my translation).

There is indeed extensive evidence of Augustus’ interest in the revival of ancient religious practices, starting with the fact that, towards the end of his life, he himself recorded that:

-

“I have been pontifex maximus; augur; quindecimvirum sacris faciundis (a member of the college responsible for sacred rites); septemvirum epulonum (a member of the college responsible for sacred feasts); an arval brother; a sodalis Titius; [and] a fetial priest” (‘Res Gestae’, 7).

The last three priestly colleges had fallen into abeyance by the late Republic and were apparently revived by Octavian/ Augustus, along with other religious revivals documented in our surviving sources. However, I suggest below that archeological evidence from Campo dell Fiera might suggest an earlier date. In order to pursue this line of enquiry, we need to consider how likely it is that this had been the locus for the (presumably annual) meetings of the both the original and the revived federation.

Meetings of the Revived Federation at Campo della Fiera ?

Plan of the excavated site at Campo della Fiera, Orvieto

From M. Cruciani (referenced below, Figure 2, p. 176) , my additions in red

As Marco Ricci (referenced below, p. 23 and note 83) pointed out, there is no hard evidence that allows us to identify the place at which the meetings of the revived federation were held. Indeed, we do not even know whether there was a single location, or whether, for example, one or more meetings were held each year in the city from which that year’s praetor had been selected. Nevertheless, as noted above, Ricci reasonably suggested (at p. 17) that Augustus had:

-

“... fostered the rebirth of the ancient Etruscan league ... in the context of his policy of the restoration of cults and the exaltation of the local traditions ...”

This suggests that he would have favoured the fanum Voltumnae. I argued in my page Etruscan Federation and Fanum Voltumnae (431 - 389 BC) in favour of the hypothesis that the original fanum Voltumnae can be identified with the sanctuary that has been excavated at Campo della Fiera (illustrated above). However, Propertius (in the elegy that he wrote in the form of a monologue delivered by a Roman statue of Voltumna, whom he called by its Roman name, Vertumnus) had this statue insist that:

-

“I am a Tuscan born of Tuscans, [but] do not regret abandoning Volsinii’s hearths in battle” (‘Elegies’ 4.2).

Clearly, at least at the time of Propertius (and thus of Augustus), the fanum Voltumnae was traditionally located at Volsinii, but its presiding deity, Voltumna/ Vertumnus, resided in Rome. We must therefore consider the archeological evidence from Campo della Fiera in this historical context. It seems that, before the events of 264 BC, at least three and possibly four temples (labelled by the excavators as A-D - see the plan above) were in use here. However, as Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2013a, at p. 651) observed:

-

“The clashes with Rome cannot have left [them] unscathed: what seems certain at the moment is that, neither in Temple B nor in Temple C, did the cult continue to function [thereafter]: worship [in this period] was reserved for Temple A, where the temenos wall was restored several times.”

Thus, if the revived federation did indeed meet at Campo della Fiera, then the evidence for this should be found in and around Temple A.

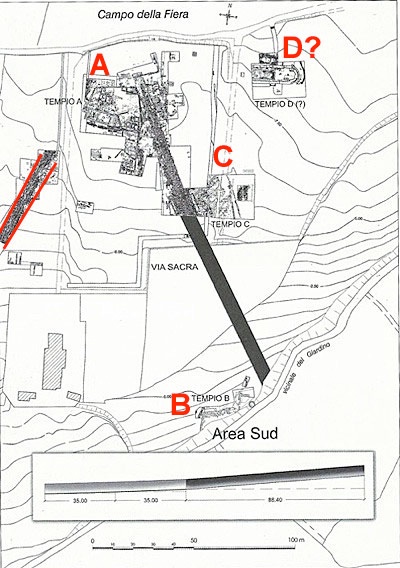

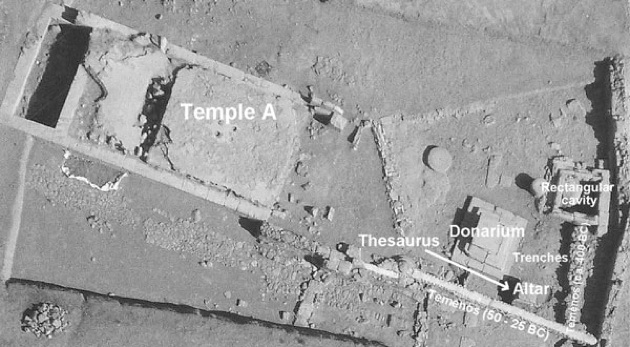

Temple A

Adapted from Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2013a, Figure 31.2 at p. 634)

3 = Temple A; 4 = rectangular cavity; 5 = donarium; 6 = trenches; 7 = thesaurus; 8 = altar;

10 = earliest temenos; 12 = third temenos (50 - 25 BC); 14 = Via Sacra

Aerial view, adapted from Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2011, Figure 19, at p. 24)

Restoration of Temple A (50 - 25 BC)

According to Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2013a, at pp. 633-4), although the original date of the construction of this small temple is unknown:

-

“... it certainly existed in the 4th century BC ... Further intervention between 50 and 25 BC sees the resurfacing of the floor, [which was] decorated with inlays of stone fragments and bicolour motifs.”

She also noted (at pp. 642-3) that the site had witnessed:

-

“... a progression of different enclosing walls, ... [the oldest of which, marked 10 on the plan above] ... may be assigned to a period between the 5th and the 4th century BC, and is aligned with the eastern side of the [rectangular cavity] ... A third wall, built in opus reticulatum, [extends the side wall of the temple and encloses] an area that includes the monuments evidently considered to be the most significant ([the temple itself], the altar, the thesaurus, the donarium and [the rectangular cavity. ... These] walls in opus reticulatum are to be connected to the resurfacing of the floor of Temple A.”

Other developments that were probably or possibly associated with this restoration include the following:

-

✴a large umber of ancient votive objects from elsewhere on the site were buried in a rectangular cavity and the two ditches in the reduced sacred enclosure; and

-

✴a number of coins were ritually deposited in the thesaurus in front of the Temple A.

Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2013b, at p. 138) suggested that this restoration was:

-

“... inspired by the political propaganda of [Octavian/] Augustus, aimed at promoting the revitalisation of ancient traditions” (my translation).

I would like to suggest that an analysis of the contents of the thesaurus potentially supports this hypothesis.

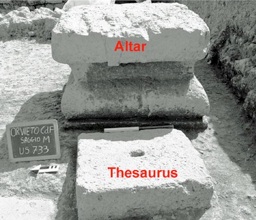

Coins Deposited in or near the Thesaurus in ca 38-15 BC

Thesaurus and altar Coins from the thesaurus

Adapted from S. Ranucci (referenced below, 2009, Plate II) Museo Archeologico, Orvieto

Samuele Ranucci (referenced below, 2009 and 2011) described the contents of the thesaurus (a stone container with an opening in its lid that was used for the collection of coins) that had been found in tact in 2008 in front of the tufa altar (illustrated on the left, above). At the time of this discovery, a thick layer of ash and coals from sacrifices rested against the altar, covering part of the thesaurus lid, including the hole through which coins were inserted. The ash itself contained a number of coins, the latest of which (RIC I: 389) dated to ca. 15 BC: by this time, therefore, the thesaurus was no longer in use (although, as explained below, six coins were subsequently pushed under its lid).

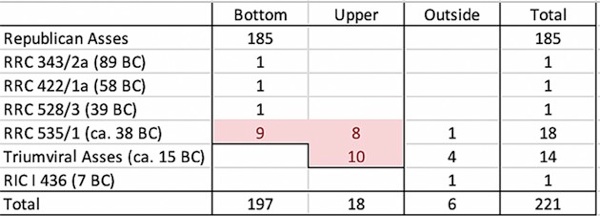

The coins in the thesaurus (most of which are now in the Museo Archeologico, Orvieto, as illustrate above) had been deposited in three distinct phases:

-

✴Those in the lower phase, which were mingled with the remains of a sacrifice, comprised:

-

•185 republican asses, with the dateable examples from the period 211-91 BC, together with:

-

-a quiniarius (RRC 343/2a) of 89 BC;

-

-a denarius (RRC 422/1a) of 58 BC; and

-

•ten coins from the triumviral period, made up of:

-

-a denarius (RRC 528/3) of 39 BC that commemorated Octavian and Mark Antony; and

-

-9 of the 18 coins in the thesaurus that commemorated Octavian and divus Julius (RRC 535/1, referred to below as divus Julius bronzes).

-

The coins in this phase had probably been donated separately (either in the thesaurus or elsewhere in the sanctuary) and ritually re-deposited in the thesaurus at some time after ca. 39 BC.

-

✴The coins in the layer above this ‘single deposition’, which were obviously donated subsequently and possibly separately before the thesaurus was covered by ash, comprised:

-

•another 8 of the 18 divus Julius bronzes (RRC 535/1); and

-

•10 of the 14 asses in the thesaurus that commemorated Octavian as Augustus in ca. 16-5 BC (RIC I: 373; 376; 379; 382; 386; and 389).

-

✴As mentioned above, 6 coins were subsequently pushed under the lid of the thesaurus. These comprised:

-

•the last of the 18 divus Julius bronzes (RRC 535/1);

-

•the last 4 of the 14 asses that commemorated Octavian as Augustus in ca. 16-5 BC; and

-

•an as issued by M. Maecilius Tullus in 7 BC (RIC I 436).

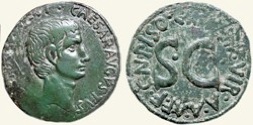

Divus Julius Bronzes in the Thesaurus

‘Divus Julius bronze’ (RRC 535/1)

Obverse: CAESAR DIVI·F: head of Octavian (bearded)

Reverse; DIVOS IVLIVS: head of Caesar (wreathed)

As we have seen, 18 divus Julius bronzes were found in the thesaurus:

-

✴9 in the single deposition at the bottom; and

-

✴9 in the layer above them, one of which had been pushed under the lid at some time after the sacrifice.

Coins in which Octavian was commemorated as f. divus Julius (or the equivalent) appeared in a number of issues in the short period between the Perusine War (41-40 BC) and Octavian’s victory over Sextus Pompeius at the Battle of Naulochus (36 BC):

-

✴The earliest of these were issues in gold or silver minted by the moneyers Ti Sempronius Gracchus and Q. Voconius Vitulus in 40 BC (the last two moneyers recorded at Rome until 23 BC).

-

✴This motif made its second appearance in coins from military mints in 38-7 BC, during the wars with Sextus Pompeius. These issues comprised:

-

•three issues in gold or silver by Agrippa as consul designate in 38 BC (RRC 534/1, 534/2 and 534/3); and

-

•two issues in bronze at about this time :

-

-RRC 535/1 (under discussion here); and

-

-the closely-related RRC 535/2 (which was not represented in the thesaurus).

-

✴The motif was used again in two issues in gold or silver by Octavian in 36 BC (RRC 540/1 and 540/2), immediately prior to the victory at Naulochus (after which Octavian’s mourning for Caesar officially ended, and his beard disappeared from his official portrait.

It would be reasonable to assume that Octavian’s own minting of divos Julius bronzes belonged to the period between the victory at Philippi (October 42 BC and the victory at Naucholus (September 36 BC).

Number of coins, by type, deposited in each of the bottom and the upper layer in the thesaurus,

and those subsequently pushed under the lid

However, Samuele Ranucci (referenced below, at p. 956) pointed out that most, if not all, of the bronzes in the thesaurus appear to be imitations (or replications) of this issue, which means that they could have been issued by any of Octavian’s commanders in Italy . Since two now-lost lead sling-shots found near modern Perugia, which were presumably fired by Octavian’s army during the Perusine War (41-40 BC) are inscribed Legio XI/ divom Julium (CIL XI 6721, 26b and 27), Ranucci observed that it is possible that the bronzes in the thesaurus:

-

“... were struck in the area of Perusia, not far from Volsinii, during the siege of the city in 41-40 BC.”

He pointed out that a votive deposit of coins from Castello di Mandoleto, outside Perugia, which was documented in 1710, contained:

-

“... several Republican asses, some denarii, many Augustan coins of the IIIviri, and ... 25 divos Iulius bronzes as well as imperial coins up to Severus Alexander, ... [and] it is important to note ... the absence, at both Mandoleto and [Campo della Fiera], of coins of the second type (RRC 535/2).”

However, since the single deposition at the bottom of the thesaurus contained a denarius issued in 39 BC, all of the coins in the thesaurus (including the 18 bronzes) must have been deposited in or after this date. It is possible that these bronzes were widely circulated in the area for a number of years after their issue, but it seems to me that, since the upper layer contained only 8 further bronzes and triumviral asses from two consecutive years in ca. 15 BC (see below), we should probably hypothesise two distinct ceremonial depositions:

-

✴one in or shortly after 39 BC, when soldiers stationed in northern Etruria deposited 17 locally-minted imitations of RRC 535/1 in the thesaurus, 9 in the ritual single deposit and another 8 immediately thereafter; and

-

✴another in ca. 15 BC, when the 10 triumviral asses were deposited in the thesaurus before it was sealed.

Date of the Deposition of the Divus Julius Bronzes

Our surviving sources indicate two distinct episodes of violence in Etruria in the period after 39 BC:

-

✴According to Cassius Dio, during Octavian’s absence from peninsular Italy in 36 BC:

-

“... parts of Etruria ... had been in rebellion, [but they] become quiet as soon as word came of his victory [at Naulochus in September of that year]” (‘Roman History’, 49: 15: 1).

-

✴According to Appian, even after the victory:

-

“... Italy and Rome itself were openly infested with bands of robbers, whose doings were more like barefaced plunder than secret theft. Octavian appointed [C. Calvisius] Sabinus to correct this disorder. [Sabinus] executed many of the captured brigands and, within one year, brought about a condition of absolute security” (‘Civil Wars’, 5:132).

Thus, Emilio Gabba (referenced below, at p. 100) summarised:

-

“Still in 36 BC, the entire area of Etruria was in revolt, and Octavian had to entrust ... Sabinus with the task of wiping out the armed bands that still roamed across central Italy”, (my translation).

Octavian made unusual arrangements for the administration of peninsular Italy in his absence during his second war with Sextus. According to Cassius Dio:

-

“Other matters in [Rome] and in the rest of Italy were administered by one C. Maecenas [see below], a knight, both then [i.e. in July - November 36 BC] and for a long time afterwards” (‘Roman History’, 49: 16:2).

Josiah Osgood (referenced below, at p. 323) explained the significance of this appointment:

-

“... when, in 36 BC, after Octavian’s departure from Rome, disturbances broke out, both there and in Etruria (site of the earlier Perusine War), [Octavian] ... gave Maecenas, [who was] not even of senatorial rank, police powers to settle the situation.”

The situation seems to have played out in stages, governed by the progress of the war. Appian recorded that, when Octavian’s fleet was damaged in a storm early in the campaign:

-

“In anticipation of more serious misfortune, [Octavian] sent Maecenas to Rome on account of those who were still under the spell of the memory of Pompey the Great, for the fame of that man had not yet lost its influence over them” (‘Civil Wars’, 5:99).

According to A. J. M. Watson (referenced below, at p. 99):

-

“... it seems that [this] was more of a diplomatic mission than one with a military purpose; ... because the populace in Rome began to riot, Maecenas, Octavian's principal diplomat, was sent to Rome to mollify them.”

When Octavian suffered a more serious setback off Mylae in August, Appian recorded that:

-

“He sent Maecenas again to Rome on account of the revolutionists; and some of these, who were stirring up disorder, were punished (‘Civil Wars’, 5:112).

A. J. M. Watson (referenced below, at p. 99) suggested that:

-

“The tenure of [Maecenas’] administration [of Rome and Italy] really began in mid-August, with the naval defeat ... off Mylae. As a result of this [defeat], a rebellion began in Etruria [as recorded by Cassius Dio, above] and Octavian gave Maecenas control of Rome and Italy, [with orders] to keep Rome loyal and to [suppress] the [Etrurian] rebellion ... However, before he could deal with [the latter], there was [another] outburst of unrest in Rome ... [which became] Maecenas' first objective ...”

Putting these accounts and interpretations together, we might reasonably assume that the revolt in Etruria broke out in August 36 BC and that Maecenas, who was tied up in Rome, delegated the task of suppressing it, probably to Sabinus (although no surviving source actually identifies him at this point). Sabinus’ task was made much easier by the news of the victory at Naulochus, which brought an end to the famine and simultaneously removed any hope that the rebels might have had of a rival to Octavian in the west. Thereafter, Sabinus turned his attention to the lawlessness that still engulfed the region (which might be a euphemism for a programme of reprisals against the former rebels).

Samuele Ranucci (referenced below, 2009, at pp. 124) put forward two hypotheses for the date of the ritual deposition of the coins (including the nine divus Julius bronzes) in the lowest stratum of the thesaurus:

-

✴it might have taken place soon after the minting of the divus Julius bronzes, perhaps in atonement for an act of sacrilege at the sanctuary during the preceding hostilities; or

-

✴since the bronzes were moderately worn (and since similar bronzes were used for votive purposes throughout the Julio-Claudian period), it might have taken place at a later date (albeit that this must have been prior to ca. 15 BC, when the thesaurus ceased to be used).

Ranucci himself favoured the second hypothesis. However, I think that the fact that they ha probably been minted locally for soldiers engaged in suppressing the revolt, argues in favour of the first. I would like to suggest that the ritual deposition occurred during a ceremony at Temple A that celebrated Octavian’s victory at Naulochus (September, 36 BC) and the end of the Etruscan revolt.

However, I think that the fact that all the bronzes belonged to a single issue, and thus (as noted above) had probably been minted locally for soldiers engaged in suppressing the revolt, argues in favour of a earlier date within this possible period. I also think that the iconography of these coins would have lost its significance by the latter part of the period. I would like to suggest that the ritual deposition occurred during a ceremony at Temple A that celebrated Octavian’s victory at Naulochus (September, 36 BC) and took place shortly thereafter.

Triumviral Asses in the Thesaurus

CAESAR AVGVSTVS TRIBVNIC POTEST/ SC: CN PISO CN F IIIVIR A A A F F (RIC I (Rome) 382)

As noted above, ten triumviral asses were deposited in the

he slit in the lid of the thesaurus in the sacred area of Temple A was open for monetary offerings throughout the period from the time of the ritual deposition of ca. 36 BC until ca. 15 BC, when it was blocked by the ash of a sacrifice. Each of the 18 coins deposited in this period belonged to one of the two following categories:

-

✴eight of them were divus Julius bronzes (as above); and

-

✴ten of them were asses (RIC I: 373; 376; 379; 382; 386; and 389) produced by the tresviri (the colleges of three moneyers) of ca. 16 and 15 BC, an example of which, from the second of these colleges, is illustrated above).

The ash that covered the slot contained a number of coins, the latest of which also belonged to this second category. I would like to suggest that the presence of such a restricted range of coins indicates that the thesaurus was not in use on a continuous basis throughout this period. Rather:

-

✴the eight divus Julius bronzes were probably donated soon after the original ritual deposition; and

-

✴the ten Augustan asses were probably donated during a second important ceremony in ca. 15 BC.

All of these asses had the same iconography:

-

✴their obverses depicted the head of Augustus, with the legend

-

CAESAR AVGVSTVS TRIBVNIC POTEST; and

-

✴their reverses had a legend identifying the moneyer of the issue in question, which surrounded the letters ‘S C’ (senatus consultum).

As noted above, the moneyers in question belonged to two consecutive colleges. These comprised:

-

✴C. Asinius Gallus Saloninus; C. Cassius Celer; and C. Gallius Lupercus; and

-

✴Cn. (Calpurnius) Piso; L. Naevius Surdinus; and C. Plotius Rufus.

While most scholars follow RIC in attributing these colleges to the years 16 and 15 BC respectively, Cornelis Pannekeet (referenced below, at pp. 22-9) gave a year later in each case. (i.e. 15 and 14 BC).

C. H.V. Sutherland (referenced below, at p. 105) established that the asses in these issues formed part of series in three denominations by each moneyer that commemorated the fact that the Senate had conferred particular honours on Augustus: in particular, the asses in these series commemorated the Senate’s conferral of perpetual tribunician power on him in 23 BC. According to Tacitus:

-

“... the tribunician power..., a phrase for the supreme dignity, was invented by Augustus, who was reluctant to take the style of king or dictator but [who was nevertheless] desirous of a title that indicated his pre-eminence over all other authorities” (‘Annals’, 3:56).

Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 336) described this power as:

-

“... a formidable and indefinite instrument of government ... [which would] compensate in part for [Augustus’ abdication from] the consulate and fulfil the functions (without bearing the name) of an extraordinary magistracy. From 1st July 23 BC [see below], Augustus dated his tenure of the [tribunician power] and added the name to his titulature. This was [Tacitus’ ‘phrase for the supreme dignity’] invented by the founder of a legitimate monarchy.”

John Rich (referenced below, pp. 67-8) had a similar view of the significance of Augustus’ perpetual tribunician power:

-

“Down to 23 BC, Augustus [had] accepted annual election to the consulship, no doubt invariably professing reluctance. For this to continue would have been manifestly ‘unrepublican’ ...; accordingly, in June or July 23 BC, during his absence from Rome at the Latin Festival, he resigned the consulship, enabling consequent adjustments to his powers to be put in place [through the award of perpetual tribunician power] before his return to the city.”

Syme had dated the award of these powers to 1st July 23 BC. However, as Rich pointed out (at note 79):

-

“The resignation [of the consulship in 23 BC] is reported by the fasti of the Latin Festival, but a lacuna leaves the date open in the period 14 June to 14 July.”

Although Rich did not address Syme’s date for the subsequent award of the tribunician power, he noted (again at note 79) that:

-

“There is no warrant for the common view that Augustus assumed the tribunician power on 26 June [23 BC], the date on which he adopted Tiberius in 4 AD.”

Adrian Goldsworthy (referenced below, at p. 270) observed that:

-

“In later years, great stress would be laid on [Augustus’] tribunician power, and his reign would be dated according to the number of years that he had held it, a pattern followed by his successors.”

In fact, while the practice continued unchanged in most respects after Augustus’ death in 14 AD, the date of the annual renewal changed:

-

-for the rest of the century, emperors renewed their tribunician power on the anniversaries of their respective dates of accession; and

-

-thereafter, most emperors renewed it each 10th December.

Returning now to the thesaurus at Campo della Fiera, it seems to me to be extremely significant that all of the coins that were deposited in it after the initial ritual deposition of ca. 36 BC, apart from 9 divus Julius bronzes, shared the TRIBVNIC POTEST/ SC iconography:

-

✴most of these:

-

•10 of the 18 coins that were deposited it through the hole in its lid in this period (as well as the most recent of the coins in the ash that covered the lid); and

-

•4 of the 6 that were pushed under the lid thereafter;

-

were asses from the ‘moneyer issues’ of ca. 16-5 BC (RIC I: 373; 376; 379; 382; 386; and 389; and

-

✴another of the 6 coins pushed under the lid, which was an as (RIC I 436) issued by M. Maecilius Tullus in 7 BC, had the same iconography, albeit that its obverse also commemorated Augustus as pontifex maximus (the priesthood he took over on the death of Lepidus in 13 BC).

Furthermore, the college of moneyers of ca. 15 BC produced seven other issues of asses (RIC I: 390-6) with the TRIBVNIC POTEST legend - but with the the head of Numa Pompilius instead of “SC” on their reverses - and none of these was represented in the thesaurus. I believe that, given this evidence, we can reasonably assume that the ceremony of ca. 15 BC specifically celebrated the Senate’s conferral of perpetual tribunician power on Augustus in June or July 23 BC.

More specifically, I would like to suggest that the ten asses that were deposited in the thesaurus before the sacrifice that effectively closed it commemorated ten full years of Augustus’ tribunician power. On that basis, the ceremony can be more precisely dated to June or July 14 BC.

Rite of the Clavus Annalis at Temple A ?

Bronze nails from Campo della Fiera, now in the Museo Archeologico, Orvieto

Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, at p. 635) reported the discovery of a number of bronze nails, some of which appeared to have been unused, along the southern wall of Temple A and gave the following assessment of their significance:

-

“The most likely interpretation of [these] nails is for [the fixing of] architectural terracottas, but the presence of such a large number of specimens raises the appeal to the Volsinian tradition of the clavus annalis [annual nail], which was [originally] affixed to the temple of the goddess Nortia, recognised by some in the Orvietan Belvedere Temple.”

The significance of this ancient rite as it was practiced in Rome was summarised by Verrius Flaccus and epitomised by Festus:

-

“The ‘clavus annalis’ [annual nail] was so called because it was fixed into the walls of the [Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus] every year, so that the number of years could be reckoned ...” (‘De verborum significatu’, 49 Lindsay).

The existence of the rite at Volsinii was recorded by Livy, who relied on:

-

“Cincius, a careful writer on such [inscriptions or monuments], [who] asserts that there were seen at Volsinii also nails fixed in the temple of Nortia, an Etruscan goddess, as indices of the number of years” (‘Roman History’, 7:3).

In my page on the Etruscan Federation, I suggested that, although (as many scholars have suggested) the rite probably had its roots in the annual meetings of the original Etruscan Federation at the fanum Voltumnae, Cincius was more probably describing the celebration of the rite at Temple A (now rededicated to Nortia) by the people of the ‘new’ Volsinii from 264 BC.

There is no way of knowing whether the rite continued to be held here into the triumviral and early imperial periods. However, I would like to suggest that it was either adapted or revived from June or July 13 BC. On this model:

-

✴the ritual deposition of the 10 coins in the thesaurus in June or July 14 BC commemorated the first 10 years of Augustus’ tribunician power (as discussed above); and

-

✴thereafter, nails of the type illustrated above were driven at Temple A to record the annual renewal of the tribunician power of Augustus and then (from his death in 14 AD) of his successors.

IN CONSTRUCTION FROM THIS POINT

Phase I: Deposition of ca. 38 BC

Maecenas

According to John Hall (referenced below, at pp. 168-9)

-

“Approximately [six Etruscans] could be counted among his closest and most influential advisors, with Agrippa and Maecenas ultimately rising to occupy positions of great authority ...”

While there is no evidence (as far as I am aware) that Agrippa, who came from Pisa, attached particular importance to what might have been considered his Etruscan roots, the case of Maecenas, who came from Arretium (Arezzo), is very different. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 68) summarised the evidence for his ‘Etruscan’ pretensions:

-

“... Tacitus [‘Annals’, 6:11:2] refers to him as Cilnius Maecenas. ... it is clear that [the equestrian Maecenas] must have been closely related to the [noble and ancient Aretine family of the] Cilnii, and it is often argued that his mother was a Cilnia. On several occasions, poets refer to [his] descent from [Etruscan] princes ...”

Propertius referred to:

-

“Maecenas, Etruscan eques (knight) of royal blood, keen not to rise above your rank ...” (‘Elegies’ 3.9).

Maecenas could thus claim among his ancestors men who might have presided over the annual meetings of original Etruscan Federation, as lucumones (kings of the 12 Etruscan city states) or sacerdotes (the priests who replaced them in this capacity after the regal period). Any thoughts of reviving the federation would have been premature at this early stage in Octavian’s career. However, we might reasonably assume that Maecenas would already have appreciated the propaganda value of any measure that associated Octavian with the ex-federal sanctuary.

As noted above, we do not know whether Volsinii had been a centre of the rebellion. However, whether or not this had been the case, its status as the last Etruscan city to have withstood the original advance of Rome and its ownership of the ex-federal Etruscan sanctuary would surely have made it an attractive centre for any propaganda programme in Etruria thereafter. Furthermore, we might expect that the Etruscan Maecenas would have played a prominent role in any such programme.

Conclusions

On the basis of the analysis above, I suggest that, after the victory at Naulochus and the end of the Etrurian revolt, the Volsinian sanctuary at Campo della Fiera became one of the centres of a propaganda programme organised by Maecenas and Sabinus that aimed to establish a newly-benign image of Octavian in Etruria. The surviving circumstantial evidence for this comprises:

-

✴the bust of Octavian found at Volsinii , which was probably commissioned by Sabinus and which was possibly used initially to associate Octavian with the cult of Nortia at Campo della Fiera; and

-

✴the ritual deposition in 36 BC or shortly thereafter of votive coins in the thesaurus of one of the altars in the sacred area of the Temple of Nortia there (evidenced by the votive offering of coins that included 18 divus Julius bronzes), at which point the altar itself was possibly rededicated to divus Julius.

Maecenas (again)

Augustus was in Gaul in the period 16-13 BC, the period in which this second ceremony at Campo della Fiera took place. Cassius Dio described his (alleged) motivation for this absence and (less contentiously) the arrangements that he had made for the administration of Italy in his absence:

-

“[In the summer of 16 BC, Augustus] set out for Gaul ..., making the wars that had arisen in that region his excuse. For, since he had become [unpopular in Rome] ..., he decided to leave the country, somewhat after the manner of Solon. Some even suspected that he had gone away on account of Terentia, the wife of Maecenas, and intended ... to live with her abroad free from all gossip. ... [He] committed the management of [Rome] and the rest of Italy to [T. Statilius Taurus], since he had sent Agrippa again to Syria, and since he no longer looked with equal favour upon Maecenas, because of the latter's wife ...” (‘Roman History’, 54:19:3).

We need not believe all of this gossip about Augustus and Terentia, but it is certainly true that, for whatever reason, Maecenas was no longer involved in public affairs in the way that he had been at the time of the Etruscan revolt (above). According to Kenneth Reckford (referenced below, at p. 198):

-

“The [few] facts that we do possess point to one simple and unromantic conclusion: Maecenas went into voluntary semi-retirement after 29 BC. [The most important reason was that], as early as 29 or 28 BC, Maecenas was a very sick man [albeit that he did not die until 8 BC].”

Semi-retirement and ill health need not have precluded Maecenas’ promotion of the ceremony at Campo della Fiera in 14 BC, especially if (as I suggested above) he had been instrumental in the cult activity here some twenty years earlier. We might identify his possible agent in this second endeavour as L. Seius Strabo.

However, with ancient Volsinii destroyed, Voltumna/ Vertumnus resident in Rome and all of Etruria now in Roman hands, any residual cult activity here would have lost all vestiges of its pan-Etruscan character. The plan above probably holds the key to the function of the sanctuary in this later period: it shows the remains of paved road (on the left, picked out by two parallel red lines) that ran southwest from Temple A: according to Simonetta Stopponi (referenced below, 2013a, at p. 633) this road:

-

“... was built in the mid 3rd century BC. The track, [which is now] exposed for more than 50 meters, was five meters wide and furrowed by the passage of wagons, connecting Orvieto with Bolsena.”

This road must have constituted an ‘umbilical cord’ some 10 km long, linking the displaced people on the shores of Lake Bolsena to what remained of their ancient city and ancient religion.

I suggested in my page on the Etruscan Federation that Temple A was probably rededicated to Nortia in or soon after 264 BC, and that this largely accounts for the fact that the cult of this deity in her Etruscan form survived at Volsinii into the 4th century AD.

L. Seius Strabo

Strabo was born in Volsinii in ca. 46 BC and was of equestrian rank. He is first mentioned in our sources by Tacitus, in a passage that described the events that followed the death of Augustus in 14 AD:

-

“The consuls, S. Pompeius and S. Appuleius, first took the oath of allegiance to Tiberius Caesar [Augustus’ successor]. It was [then] taken ... by Seius Strabo and C. Turranius, chiefs respectively of the praetorian cohorts and the corn department” (‘Annals’, 1:7).

We do not know when Strabo secured the post of Pratorian Prefect (head of the imperial bodyguard), which was introduced in 2 BC. However, its importance is clear from the career of his son, Sejanus, who succeeded him in the post and who used it to dominate Rome until his assassination in 31 AD:

-

✴Tacitus recorded that Sejanus first shared the post with his father:

-

“The commandant of the household troops, [Sejanus], who held the office jointly with his father Strabo and who exercised a remarkable influence over Tiberius, went [with the army to Pannonia in 15 AD] ... ” (‘Annals’, 1:24).

-

✴Cassius Dio recorded that Strabo was then promoted:

-

“... Sejanus ... had shared for a time his father's command of the Pretorians; but, when his father had been sent to Egypt, ... he had obtained sole command over them ...” (‘Roman History’ 57:19).

Thus, Strabo ultimately became Prefect of Egypt, which was the pinnacle of an equestrian career. According to Robert Rogers (referenced below, at p. 369):

-

“Strabo appears to have died in [this] office ... [his tenure had extended from] ca. 15 until 16 or 17 AD.”

Strabo is almost certainly commemorated in two inscriptions from Volsinii. Both of these inscriptions have been mutilated, and neither preserves (or at least fully preserves) the name of the man commemorated: we might reasonably assume that this mutilation took place after the assassination of Sejanus in 31 AD. The surviving fragments read:

-

✴CIL XI 2707; EDR 079089 , from an unknown location at Volsinii and now lost, read:

[...]

[...]aboni

[pra]efecto

[pra]etori

-

We might reasonably assume that the Praetorian Prefect [...]aboni was L. Seius Strabo, and that the inscription pre-dated his appointment as Prefect of Egypt in 15 AD.

-

✴CIL XI 7285; EDR 079090 from Poggio Moscini, now in the Museo Archeologico, Florence, reads:

[.....]

praefectus Aegypt[i et]

Terentia A(uli) f(ilia) mater eiu[s et]

Cosconia Lentulii(!) Malug[inensis f(ilia)]

Gallitta uxor eius ae[dificiis]

emptis et ad solum de[iectis]

balneum cum omn[i ornatu]

[Volsiniens]ibus ded[erunt]

[ob publ]ica co[mmoda]

-

This inscription records the fact that a now-anonymous Prefect of Egypt, together with his mother and his wife, had built and decorated a ‘balneum’ (bath house) for public use. Some scholars have doubted that this Prefect of Egypt was Strabo (see for example, Pierre Gros,referenced below, 2013, at p. 95), but this view seems to be losing ground. For example, Francis Cairns (referenced below, at p. 21, note 109) observed that:

-

“[Ronald] Syme [referenced below, at pp. 301-4] convincingly recovers CIL XI 7285 for L. Seius Strabo.”

-

If this is correct, then the inscription dates to ca. 15 AD and reveals the following:

-

•Strabo’s wife (perhaps his second wife) was Cosconia Gallitta, the daughter of Cornelius Lentulus Maluginensis, the suffect consul of 10 AD.

-

•More importantly for our present purposes, his mother, Terentia, was the daughter of ‘Aul.’:

-

-this was probably Aul. Terentius Varro Murena, whom Augustus executed for treason in 24 BC (see, for example, Ronald Syme, referenced below, at p. 301);

-

-in which case, Strabo’s mother was the niece of another Terentia - the sister of the executed Murena and the apparently wayward wife of Maecenas.

Despite the family’s success in Rome, its Etruscan roots and its continuing links to the Volsinian goddess Nortia is suggested in a poem by Juvenal, in which he muses on the behaviour of the Roman mob following the disgrace and murder of Sejanus:

-

“But what of the Roman mob?

-

They follow Fortune, as always, and hate whomever she condemns.

-

If Nortia, as the Etruscans called [Fortuna], had favoured Etruscan Sejanus;

-

If the old Emperor [Tiberius] had been surreptitiously smothered [to clear the way for him];

-

That same crowd ... would have hailed [Sejanus as] their new Augustus” (‘The Vanity of Human Wishes’ - search this link on ‘Nortia’).

The material presented here provides only circumstantial evidence for the possible involvement of Seius Strabo in the events at Campo della Fiera of 14 BC. Nevertheless, I find it tempting to ‘implicate’ him, because of: the apparent rapidity of his rise under Augustus; his family connection to Maecenas; the fact that he came from Volsinii and seems to have been one of its most prominent citizens; and the fact that his family (or at least his son) was closely associated in Rome with both Etruria and Nortia.

Conclusions

In the section above (headed ‘Phase I’), I suggested that, after Octavian’s victory at Naulochus in 36 BC, the Volsinian sanctuary at Campo della Fiera became one of the centres of a propaganda programme organised by Maecenas and Sabinus that aimed to establish a newly-benign image of Octavian in Etruria. In particular, I suggested that:

-

✴Octavian was formally associated with the cult of Nortia at at Temple A; and

-

✴the altar in the sacred enclosure of the temple that hosted the thesaurus described above had been rededicated to his deified ‘father’, divus Julius.

In the section here (Phase II), I discussed a second ceremony that also involved the thesaurus at Campo della Fiera, this time in June or July 14 BC, by which time the triumvir Octavian had become the Emperor Augustus. I suggested that Maecenas had once again been the instigator of this ceremony, this time in association with the Volsinian L. Seius Strabo. In particular, I suggested that:

-

✴the 10 coins that were deposited through the lid of the thesaurus at this time commemorated the first 10 years of Augustus’ tribunician power; and

-

✴the rite of the clavus annalis at the nearby Temple A was either adapted or revived so that, thereafter, nails were driven there to record the annual renewal of the tribunician power of Augustus and (from 14 AD) of his successors.

In what follows, I suggest that this second ceremony at the sanctuary at Campo della Fiera coincided with the revival there of the Etruscan Federation.

Revival of the Etruscan Federation

Enrico Zuddas (referenced below) suggested that the temple at Volsinii dedicated to Nortia (wherever was its precise location) might have adopted the rite of the clavus annalis after the revival of the federation. Specifically, he drew attention (at p. 226) to the anonymous praetor Etruriae from Volsinii in the mid 3rd century AD who was commemorated in CIL XI 7287 (above), and pointed out that this man had also held the post of:

-

“ ... ‘curator templi deae Nortiae’ (responsible for the maintenance, decoration and restoration of [a temple of Nortia]: this, of course, does not necessarily mean that he undertook this activity [in his capacity] as praetor ...) He has been identified as a member of the gens of the Rufi Festi, which was particularly devoted to [Nortia]” (my translation).

Zuddas noted that:

-

✴according to Mario Torelli [reference to follow], Nortia had probably ‘taken over’ from Veltumna after the destruction of the federal sanctuary at Volsinii in 264 BC; and

-

✴Livy, following Cincius, had attested the rite of the clavus annalis in honour of this goddess at Volsinii.

On the basis of these observations, he suggested (at p. 227) that this rite:

-

“... could have been reprised by the praetor Etruriae [of the revived federation], with reference to the function of the ancient presidents of the [original] Etruscan league” (my translation).

If I am correct in placing the annual meetings of the revived federation at Campo della Fiera, then we might reasonably assume that:

-

✴the anonymous from Volsinii who was commemorated as the ‘curator templi deae Nortiae’ in the 3rd century AD was actually the curator of Temple A; and

-

✴he presided over the rite of the clavus annalis there in the year that he held the priesthood of praetor Etruriae (albeit that, as Zuddas reasonably pointed out, the two posts were not necessarily held concurrently).

On the basis of Zuddas’ suggestion and the other material above, I would like to suggest that:

-

✴the ceremony at Campo della Fiera that took place in June or July 14 BC marked both:

-

•the 10th annual renewal of Augustus’ tribunician power (as discussed above); and

-

•the revival of the Etruscan Federation; and

-

✴thereafter, each newly-elected Praetor Etruriae (XV Populorum) presided over the annual meetings of the federation there, during which he drove the annual nail to mark:

-

•the annual renewal of the tribunician power of the ruling emperor (as discussed above); and

-

•the start of his own year in office (as had apparently been the case for the sacerdotes of the original federation).

As I pointed out above, Maecenas could claim among his ancestors men who had probably attended and possibly presided over the annual meetings of original Etruscan Federation. I also argued above that he had probably choreographed both ceremonies at Campo della Fiera:

-

✴In 36 BC or shortly thereafter, any thoughts of reviving the Etruscan Federation would have been premature.

-

✴However, in 14 BC, Octavian was now the Emperor Augustus and the political climate had been transformed. In my view, it entirely possible that, in the context of the second ceremony at Campo della Fiera, he master-minded the revival of the Etruscan Federation and instituted the practice by which its annual meetings there would commemorate the annual renewals of Augustus’ tribunician power.

Annual Games and Theatrical Performances

Aerial view, with modern Bolsena (at the lower left )

The original forum of Volsinii was at Mercatello, the later the site of the Flavian amphitheatre

The site of the ‘Flavian’ forum is now the Archeological Area at Poggio Moscini

Livy recorded that, when the king of Veii had appealed to the other members of the original Etruscan Federation against Rome in 403 BC, they refused, in part because he had caused offence when, on an earlier occasion, he had:

-

“... violently broken off the performance of some annual games (the omission of which was deemed an impiety) ... because another had been preferred to him as a priest by the votes of the 12 states: ... in the middle of the performance, he suddenly carried off the performers, most of whom were his own slaves. ” (‘Roman History’, 5:1).

From this, we learn (inter alia) that the annual meetings of the original federation involved annual games and theatrical performances. We can therefore reasonably assume that these were also characteristic of the annual meetings of the revived federation.

However, as Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 227) pointed out:

-

“... archaeological investigations [at Campo della Fiera] have not revealed ... facilities [for games and theatrical performances], although the wide open spaces there would have accommodated them” (my translation).

This is perhaps unsurprising in relation to the situation before 264 BC, when the facilities in question might well have been temporary structures. However, had Campo della Fiera hosted the annual pan-Etruscan games and theatrical performances of the revived federation from the early imperial period, one might have expected to find evidence of monumentalised facilities of the kind found, for example, at the colony of Hispellum (which Augustus, then the triumvir Octavian, had established in ca. 40 BC). I would like to suggest that there were, in fact, two loci for the meetings of the revived federation:

-

✴the ritual of the federation, including the consecration to the annually elected praetor, took place at the sanctuary at Campo della Fiera; and

-

✴the games and theatrical performances took place at Volsinii itself.

As noted above, these two locations were linked by the ancient road, part of which is highlighted in the aerial view of the site of Campo della Fiera.

The evidence for a theatre and amphitheatre at Volsinii is set out in my pages on Orvieto: Volsinii in the Early Empire and in the Imperial Period). Briefly:

-

✴An inscription (CIL XI 2710, EDR 127700) from località Mercatello (the site of the original forum, at the upper right in the aerial view above) reveals the existence of a theatre of some kind in the 1st century BC, albeit that no undisputed evidence exists for tits status or location.

-

✴The forum was moved towards Lake Bolsena in the Flavian period (to the site marked at the centre left in the aerial view above), at which point the terrace at Mercatello was used for a new and impressive amphitheatre, the remains of which survive.

It is possible that a theatre and amphitheatre of some kind were established on the site of the original forum at the time that the federation was revived.

-

✴The amphitheatre that was built here in the Flavian period might well have served the revived federation.

-

✴The theatre that is known from the inscription here might have been demolished to make way for this new amphitheatre and rebuilt in an unknown (but possibly nearby) location.

Thus, it is entirely possible that the ancient ‘umbilical cord’ mentioned above linked Temple A, the putative Temple of Nortia at Campo della Fiera, to the amphitheatre and theatre of Volsinii, and that, from 14 BC, this complex served the ritual needs of the revived federation.

Revived Federation and the Imperial Cult

Marco Ricci (referenced below, at p. 19) observed that:

-

“It does not seem absurd to connect the post [of praetor Etruria], more or less directly, with the imperial cult; in favour of this hypothesis [are the following]:

-

✴attestations [of the priesthood and the imperial cult ?] continued into the 4th century AD;

-

✴the early holders of this office (as with provincial priesthoods of the imperial cult) had municipal backgrounds; and

-

✴above all, Augustus was not reluctant to accept, even in Italy, the cult of his person, as evidenced by an Etruscan city such as Perugia [where sacred groves were dedicated to him during his lifetime, as mentioned below]” (my translation).

In this context, Ricci noted (at pp 18-19 and note 57) that two praetores Etruriae also held priesthoods that are securely linked to the imperial cult:

-

✴Aul. Vicirius of Saena was a flamen augustale; and

-

✴C. Betuus Cilo of Perusia was a ‘sacerdozio trium lucorum’, a priest of three groves at Perusia that were sacred to Augustus [mentioned above].

He might have added that:

-

✴the inscription commemorating the anonymous of Rusellae came from the so-called ‘Vano delle Statue’, a room of that had also housed a number of Julio-Claudian statues and which had probably served as the municipal Augusteum; and

-

✴the relief from Caere (illustrated at the top of the page) was found (again, near a number of Julio-Claudian statues) in what seems to have been a meeting place for the Augustales.

Marco Ricci touched on the circumstances in which the revival might have taken place: he pointed out (p. 19) that the two earliest known praetores Etruriae:

-

✴S. Valerius Proculus, commemorated in two inscriptions from Vettona (early 1st century AD); and

-

✴[C. ?] Metellius, one of two men of this name commemorated on an inscription from Cortona (first half of the 1st century AD;

came from cities that had been:

-

“... affected by the Perusine War [of 41-40 BC] and the viritane settlement of the triumviral and Augustan periods. [This] suggests that the reconstituted federation was based, at least initially, on the support of the new municipal élites that had been imposed by [Octavian], which were therefore well disposed to the worship of his person” (my translation).

The scenario that I have developed above is obviously consistent with these observations. However, I have a difference of emphasis in two main respects:

-

✴I assume a more pro-active role for Octavian/ Augustus, driven by Maecenas; and

-

✴I suggested that the revived federation was linked to the imperial cult by having its annual meetings celebrate the annual renewal of imperial power.

The context for this second proposition is usefully provided by Duncan Fishwick (referenced below), who recently outlined the development of the imperial cult under Augustus. This had begun in the east, soon after his victory over Mark Antony at Actium in 31 BC, when the koiná (ethnically-based associations of cities) of both Asia and Bithinia requested and received permission for the construction of sacred precincts for Roma and Augustus at Pergamum (Asia) and at Nicomedia (Bithinia). Things were more complex in the west, where there was no established tradition of ruler cults: indeed, it is possible that Julius Caesar had died as a result of his attempts to move too quickly in this direction. As Fishwick summarised in his abstract (at p. 47), Augustus, in fact, had to address three very different ‘audiences’:

-

✴“Faced with the worship of the ruler in the Greek east, Augustus could do little more than regulate [and adapt] a practice that had already existed over three centuries [beginning in Asia and Bithnia, as described above].”

-

✴“His problem in Rome ... was to adapt the cult of the ruler ... to the usage of the Republic in such as way as to distance himself from Caesar ... The system he hit upon was to emphasise republican forms, key abstractions, and the worship of state gods closely connected with his rule: in other words to establish the cult of the emperor by other than direct means.”

-

✴“In the Latin west [by which he means the western provinces], ... he was free to shape the ruler cult as he chose [since there were no earlier traditions of this kind in these regions]. His principal contribution here was to establish regional centres at Lugdunum and elsewhere for the worship of Roma and Augustus, a prescription originally laid down for non-Romans in the Greek east [as described above].”

Federal Altar at Lugdunum

CAESAR PONT MAX/ ROM ET AVG (RIC Augustus 230)

Before we consider Augustus’ options in Etruria, we might usefully start at Lugdunum (modern Lyon). An entry in the ‘Periochae’ of Livy that relates to 12 BC reads:

-

“The Germanic tribes living on this side of the Rhine and across the Rhine were attacked by Drusus, and the uprising in Gaul, caused by the census, was suppressed. An altar was dedicated to the divine Caesar at the confluence of the Saône and Rhône, and a priest was appointed, C. Julius Vercondaridubnus” (‘Periochae’, 139)

Suetonius seems to give a slightly later date:

-

“[The future Emperor] Claudius was born at Lugdunum on the Kalends of Augustus in the consulship of Iullus Antonius and Fabius Africanus [i.e. in 10 BC], the very day when an altar was first dedicated to Augustus in that town ...” (‘Life of Claudius’, 2)

However, most scholars follow Duncan Fishwick, who suggested (at pp.18-9) that the altar was dedicated in 12 BC, and that Claudius had probably been born two years later, on the dies natalis of the altar. The dedication was marked by the issue of two coins from the mint at Lugdunum:

-

✴a sestertius (RIC Augustus 229) and

-

✴an as (RIC Augustus 230).

Both denominations had the same obverse and reverse designs:

-

✴the obverse legend ‘CAESAR PONT MAX’ indicates that they post-date 6th March 12 BC, when Augustus became Pontifex Maximus; and

-

✴the reverse motif suggests that the altar was decorated with the corona civica and laurels and was flanked by figures of victory.

As Fishwick succinctly explained (at pp. 54-5):

-

“The key event in the Augustan extension of the ruler cult in the west was the establishment of an altar that served as the focal point of the federal centre a kilometre or so upstream from the colony of Lugdunum ... [This cult site] served a region rather than a province, in this case the administrative units of Lugdunensis, Aquitania and Belgica. ... The principal features of the altar [there] ... are familiar from coins, as is the historical context of its foundation, an attempt by Drusus [Augustus’ son-in-law, who was his legate in Gaul in 13-9 BC] to counter local discontent over the census. As [Cassius] Dio confirms, the initiative came from the Roman side, its purpose presumably served by the prospect of the formation of a council chaired by the holder of the priesthood of the Three Gauls and attended by delegates from the three regions, who now had a central meeting place to air their grievances, praise or blame the provincial governor, and compete for the prestigious post of high priest. The number of delegates is uncertain, since some of the 64 Gallic tribes appear to have sent more than one delegate, but a number between 100 and 300 seems a reasonable estimate. ... The date of dedication of the altar is generally taken to have been 12 BC, from which time delegates to the [annual] concilium under the presidency of the High Priest paid cult to Roma and Augustus ad aram [at the altar], just as Octavian [shortly before he became Augustus] had originally prescribed in the east. As luck would have it, epigraphical testimony to the federal cult has survived in abundance, with the names of over 40 high priests preserved in inscriptions.”

In Etruria (and, indeed, in Italy generally), Augustus faced a situation closer to that in Rome than to that in the provinces of the west. Thus, there are no known regional altars to Augustus in Italy that pre-date his death and formal deification (albeit that things were more relaxed in the municipal context). Nevertheless, the revived Etruscan Federation shared important characteristics with the association of Gallic tribes based on Lugdunum:

-

✴both associations were ethnically based (comprising, respectively, 15 Etruscan cities and 64 Gallic tribes);

-

✴each annually selected a priest (praetor Etruriae (XV populorum) in Etruria; sacerdos (Romae et Augusti) in Gaul) from one of its constituent cities/tribes;

-

✴this priest presided over an annual concilium at a federal cult site; and

-

✴on the hypothesis above, the two associations were established at about the same time (14 BC at Volsinii, ca. 12 BC at Lugdunum).

We might reasonably assume that a number of other characteristics of the ethnicly-based association at Lugdunum also applied to revived Etruscan Federation at Volsinii:

-

✴that the initiative for its establishment (or rather, in this case, its revival) came from Rome;

-

✴that it was closely associated with the emerging imperial cult in order to provide a ‘virtual’ imperial presence in the region; and

-

✴that its other primary purpose was to create a means by which members of the local élite could gain prestige and represent the region through a direct channel of communications with Rome.

However, an altar dedicated to Augustus himself (or even to Augustus and Roma) at the sanctuary at Volsinii would have been a step too far. We should thus return to Fishwick’s summary of Augustus’ approach in Rome:

-

“The system he hit upon [there] was to emphasise republican forms, key abstractions, and the worship of state gods closely connected with his rule: in other words to establish the cult of the emperor by other than direct means.”

I suggested above that:

-

✴Augustus (while still Octavian) had already established an altar to divus Julius outside the Temple of Nortia at the ex-federal sanctuary at Volsinii, and that he was possibly formally associated with her cult there;

-

✴he revived or adapted the rite of the clavus annalis at this temple in 14 BC, so that it now commemorated the allegedly ‘republican’ annual renewal of his tribunician powers; and

-

✴he revived the Etruscan Federation at this time, replete with annually elected praetores who would (inter alia) drive the annual nail.

If these hypotheses are correct, then Augustus arguably achieved at Volsinii what he would very shortly achieve at Lugdunum, albeit that, at Volsinii, he effectively established the imperial cult for Etruria by Fishwick’s “other than direct means”.

The relief (illustrated above) waswith a number of statues of members of the Julio-Claudian dynasty at Caere (Etruscan Cerveteri)

Read more:

Laird M., “Civic Monuments and the 'Augustales' in Roman Italy”, (2015 ) New York

Liverani P. and Santoro P., “Le Théâtre et le Cycle Julio-Claudien de Cerveteri”, in:

Gaultier F. et al, (editors) ““Cerveteri : une des Grandes Métropoles de la Méditerranée Antique”, (2013) Paris, pp. 324-8

Ricci M., “Praetores Etruriae XV Populorum: Revisione e Aggiunte all’ Opera di Bernard Liou”, Bollettino della Deputazione di Storia Patria per l’Umbria, 111:1 (2014) 5-30

Pannekeet C. G. J., “The Moneyers’ Issues under Augustus”, (2013) Slootdorp

Stopponi S, (2013a), “Orvieto, Campo della Fiera: Fanum Voltumnae”, in:

Macintosh Turfa J. (editor), “The Etruscan World”, (2013 ) Oxford, pp. 632-54

Stopponi S. (2013b), “La Ricerca del Fanum Voltumnae: gli Scavi in Località Campo della Fiera”, in:

della Fina G. and Pellegrini E. (editors), “Da Orvieto a Bolsena: un Percorso tra Etruschi e Romani”, (2013) Pisa, pp. 136-47

Cruciani M., “Campo della Fiera di Orvieto: la Via sacra”, in:

della Fina G. (editor), “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, (2012) Orvieto, pp 161-82

Ranucci S., “A Stone Thesaurus with a Votive Coin Deposit Recently Found in the Sanctuary of Campo della Fiera, Orvieto (Volsinii)”, Proceedings of the XIV International Numismatic Congress), (2011) Glasgow, pp. 954-9

Stopponi S., “Campo della Fiera at Orvieto: New Discoveries”, in:

de Grummond N. T. and Edlund-Berry I. (editors), “Archaeology of Sanctuaries and Ritual in Etruria”, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplement 81, (2011) Portsmouth, Rhode Island, pp 16-44

Giontella C., “Pavimenti in ‘Signino’ (Cementizio) a Campo della Fiera, Orvieto”, in:

Angelelli C., (editor), “Atti del XIV Colloquio AISCOM: Spoleto, 7-9 febbraio 2008”, (2009) Tivoli, pp. 111-8

Ranucci S., “Il Thesaurus di Campo della Fiera, Orvieto (Volsinii)”, Annali Istituto Italiano Numismatica, 55 (2009) 103-39

Amela Valverde L., “La Emisión Divos Iulius (RRC 535/1–2)”, Iberia, 6 (2003) 5–40

Sear D., “History and Coinage of the Roman Imperators 49-27 BC”, (1998) London

Gabba E., “Trasformazioni Politiche e Socio-Economiche dell' Umbria dopo il Bellum Perusinum” in:

Catanzaro G. and Santucci F. (editors.), “Bimillenario della Morte di Properzio: Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi Properziani”, (1986) Assisi, pp 95-104

Liou B., “Praetores Etruriae XV Populorum”, (1969) Brussels

Zuddas E., “La Praetura Etruriae Tardoantica”, in:

Cecconi G. A. et al. (Eds), “Epigrafia e Società dell’ Etruria Romana (Firenze, 23- 24 ottobre 2015)”, (2017) Rome, pp. 217-35

Goldsworthy A., “Augustus: From Revolutionary to Emperor”, (2015) London

Fishwick D., “Augustus and the Cult of the Emperor”, Studia Historica, Historia Antigua

32 (2014) 47-60

Ambrogi A. and Caruso I., “Arte di Età Imperiale: i Ritratti di Costantino e di Domizia Longina”, in:

della Fina G.and Pellegrini E. (editors), “Da Orvieto a Bolsena: un Percorso tra Etruschi e Romani”, (2013 ) Pisa, pp 326-8

Gros P., “La Nuova Volsinii: Cenno Storico sulla Città”, in:

della Fina G. and Pellegrini E. (editors), “Da Orvieto a Bolsena: un Percorso tra Etruschi e Romani”, (2013 ) Pisa, pp. 88-105

Ambrogi A., “Ritratto di Augusto-Costantino”, in:

Bravi A. (editor), “Aurea Umbria: Una Regione dell’ Impero nell’ Era di Costantino”, Bollettino per i Beni Culturali dell’ Umbria, (2012), pp 128-30

Frascarelli, A., “Un Donario Monumentale a Campo della Fiera”, in:

della Fina G. (editor), “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, (2012) Orvieto, pp 131-60

Rich J., “Making the Emergency Permanent: Auctoritas, Potestas and the Evolution of the Principate of Augustus”, in:

Rivière Y. (editor), “Des Réformes Augustéennes”, Collection de l'École Française de Rome, 458 (2012) 37-121

Osgood J., “Caesar’s Legacy”, (2006) Cambridge

Cairns F., “S. Propertius: The Augustan Elegist”, (2006) Cambridge

Oakley S. P., “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X: Volume IV, Book X”, (2005 ) Oxford

Scheid J., “Augustus and Roman Religion: Continuity, Conservatism and Innovation”, in:

Galinsky K. (editor), “Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus”, (2005) Cambridge, pp. 175-96

Gradel I., “Emperor Worship and Roman Religion”, (2002) Oxford

Tamburini P., “Bolsena: Emergenze Archeologiche a Valle della Città Romana”, in:

della Fina G. (editor), “Perugia Etrusca”, Annali della Fondazione per il Museo ‘Claudio Faina’, 9 (2002) pp 541-80

Sensi L., “In Margine al Rescritto Costantiniano di Hispellum” in:

“Volsinii e il suo Territorio”, Annali della Fondazione per il Museo ‘Claudio Faina’, 6 (1999) 365-71

Hall J., “From Tarquins to Caesars: Etruscan Governance at Rome , in:

Hall J. (editor), “Etruscan Italy: Etruscan Influences on the Civilizations of Italy from Antiquity to the Modern Era”, (1996) Provo, Utah, pp. 149-90

Torelli M., “Studies in the Romanisation of Italy” (1995) Edmonton (English translation) Chapter 4, “Towards the History of Etruria in the Imperial Period”, corrects and comments on the paper by Bernard Liou referenced below.

Watson A. J. M., “Maecenas’ Administration of Rome and Italy”, Akroterion, 39 (1994) 98-104

Tassaux F., “Pour une Histoire Économique et Sociale de Bolsena et de son Territoire”, Mélanges de l'Ecole Française de Rome: Antiquité , 99:2 (1987) 535-61

Thuillier J, “Les Édifices de Spectacle de Bolsena: Ludi et Munera”, Mélanges de l'Ecole Française de Rome, Antiquité, 99:2 ( 1987) 595-608

Gros P., “Bolsena I: Scavi della Scuola Francese di Roma a Bolsena (Poggio Moscini): Guida agli Scavi”, Mélanges d' Archéologie et d' Histoire, 6 (1981)

Harris, W., “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

Weinstock S., “Divus Julius”, (1971) Oxford

Sutherland C. H.V., “The Symbolism of the Early Aes Coinages under Augustus”, Revue Numismatique, (6th series), 7 (1965) 94-109

Reckford K. J., “Horace and Maecenas”, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 90 (1959) 195-208

Rogers R. S., “The Prefects of Egypt under Tiberius”, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 72 (1941), 365-71

Syme R., “The Roman Revolution” (1939, latest edition 2002) Oxford

Return to Roman History (1st Century BC)